Abstract

Objective

Several plausible mechanisms and anecdotal descriptions suggest that gout attacks often occur at night, although there are no scientific data supporting this. We undertook this study to evaluate the hypothesis that gout attacks occur more frequently at night.

Methods

We conducted a case-crossover study to examine the risk of acute gout attacks in relation to the time of the day. Gout patients were prospectively recruited and followed up via the internet for 1 year. Participants were asked about the following information concerning their gout attacks: the date and hour of attack onset, symptoms and signs, medication use, and purported risk factors during the 24- and 48-hour periods prior to the gout attack. We calculated the odds ratios (ORs) of gout attacks (with 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs]) according to three 8-hour time blocks of the day (i.e., 12:00 am to 7:59 am, 8:00 am to 3:59 pm [reference], and 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm) using conditional logistic regression.

Results

Our study included 724 gout patients who experienced a total of 1,433 attacks (733, 310, and 390 attacks during the first, second, and third 8-hour time blocks, respectively) over 1 year. The risk of gout flares in the 8-hour overnight time block (12:00 am to 7:59 am) was 2.36 times higher than in the daytime (8:00 am to 3:59 pm) (OR 2.36 [95% CI 2.05–2.73]). The corresponding OR in the evening (4:00 pm to 11:59 pm) was 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.48). These associations persisted among those with no alcohol use and in the lowest quintile of purine intake in the 24 hours prior to attack onset. Furthermore, these associations persisted in subgroups according to sex, age group, obesity status, diuretic use, and use of allopurinol, colchicine, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Conclusion

These findings provide the first prospective evidence that the risk of gout attacks during the night and early morning is 2.4 times higher than in the daytime. Further, these data support the purported mechanisms and historical descriptions of the nocturnal onset of gout attacks and may have implications for antigout prophylactic measures.

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis in the US (1–3), and acute gout flares are among the most painful events experienced by humans (4). Several plausible mechanisms and historical and anecdotal descriptions suggest that gout attacks often occur at night; however, no scientific data are available. For example, Thomas Sydenham, the famous 17th century physician, wrote of his personal experiences with gout: “He goes to bed and sleeps well, but about Two a Clock in the Morning, is waked by the Pain, seizing either his great Toe, the Heel, the Calf of the Leg, or the Ankle; this pain is like that of dislocated Bones … the Part affected has such a quick and exquisite Pain, that is not able to bear the weight of the cloths upon it, nor hard walking in the Chamber” (5).

It has been speculated that lower body temperature, relative nocturnal dehydration, or the nocturnal dip in cortisol levels may lead to an increased risk of gout attacks at night. Another hypothesis for the typical nocturnal onset is the potential role of sleep apnea (6,7), which is common among obese men with multiple comorbidities, a typical profile of gout patients. Hypoxia associated with sleep apnea can enhance nucleotide turnover, thereby generating purines, which are metabolized to uric acid (UA) (8–10), leading to hyperuricemia in these patients (11–14). Despite these intriguing possibilities and anecdotal observations, no study has investigated the potential varying levels of the risk of gout attacks associated with the time of day. Accurate understanding of the circadian variation of gout attacks could have practical implications for effective timing of antigout prophylactic measures. To evaluate this hypothesis, we used a case-crossover design (15) to examine the risk of acute gout attacks in relation to the time of the day among 724 prospectively recruited gout patients.

Subjects and Methods

Study population and design

The Boston University Online Gout Study is an internet-based, case-crossover study that started in February 2003 with the primary aim of investigating purported triggers of recurrent gout attacks (15). As previously described in detail (15), this study design allows each participant to serve as his or her own control, and self-matching eliminates confounding by risk factors that are constant within an individual but that would differ between subjects (e.g., genetics, sex, race, and education). Such a study design has been successfully used in many previous studies in which the effect of transient risk factors on the risk of an acute event was evaluated (e.g., triggering factors for myocardial infarction) (16).

Subject recruitment

We built a study web site hosted on an independent and secure server within the Boston University School of Medicine domain (https://dcc2.bumc.bu.edu/GOUT). We prospectively recruited gout patients using the Google search engine by linking a study advertisement to search terms related to the word “gout.” Individuals who clicked on the advertisement were taken to the study web site and asked to provide the following information at study entry: sociodemographic information, gout-related data (e.g., diagnosis of initial gout attack, age at onset, antigout medication use, number of gout attacks in the last 12 months), and history of other diseases and medication use.

Subjects were considered eligible for this study if they reported physician-diagnosed gout, had a gout attack within the past 12 months, were age ≥18 years, resided in the US, agreed to the release of medical records pertaining to gout diagnosis and treatment, and provided electronic informed consent. To confirm the gout diagnosis, we obtained medical records pertaining to the subject's gout diagnosis and/or a checklist of the features listed in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) preliminary classification criteria for gout (17), completed by the subject's physician. Two board-certified rheumatologists (TN, DH) reviewed all medical records and checklist information to determine whether the subject had a diagnosis of gout consistent with the ACR criteria (17). Discrepancy was resolved by consensus. Similar methods of gout diagnosis confirmation have been used in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (18). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Boston University Medical Campus.

Ascertainment of recurrent gout attacks

We collected data regarding the onset date of the recurrent gout attack, anatomic location of the attack, clinical symptoms and signs (maximal pain within 24 hours or redness), and antigout medications used to treat the attack (i.e., colchicine, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], systemic corticosteroids, and intraarticular corticosteroid injections). Our method of identifying gout attacks is consistent with approaches used in trials of acute and chronic gout (19–21), as well as with the ACR/European League Against Rheumatism–supported initiative for defining gout attacks that includes only patient-reported elements (22). We further assessed the robustness of our case definition by restricting recurrent attacks to those treated with at least 1 antigout medication (as above), those with podagra, those with maximal pain within 24 hours, those with redness, and those with a combination of these features (i.e., flares with ≥2, ≥3, and all 4 features).

Ascertainment of onset time and purported risk factors

Participants were asked about the following information concerning their gout attacks: the date and hour of attack onset, purported risk factors, symptoms and signs, and relevant medication use during the 24- and 48-hour periods prior to the gout attack. The same list of exposure data was also collected at study entry (for those subjects who entered the study during an intercritical period) and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of followup (for those subjects who entered the study at the time of a gout attack).

Statistical analysis

Our primary analysis calculated the odds ratio (OR) of gout attacks according to three 8-hour time blocks of the day (i.e., 12:00 am to 7:59 am, 8:00 am to 3:59 pm [reference], and 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm) using conditional logistic regression. As our hypothesis was that the onset of gout attacks was more frequent at night or in the early morning than in the daytime, the time block of 8:00 am to 3:59 pm served as our reference. In this analysis, all flare episodes experienced by 724 gout patients contributed to the OR estimation as they provided an exposure-discordant pair of exposures (nocturnal onset versus daytime onset) (23).

Recurrent events in case-crossover studies require accounting for the potential within-subject correlation among recurrent events, unless the analysis is limited to the first event (23). To address this issue and fully use our data points for the precision of our estimates, our primary conditional logistic regression used the conditional likelihood method by pooling recurrent event data, under the assumption that within-subject correlation is accounted for by conditioning on subject-specific variables and other observed time-varying factors (23). With the same matching variables accounted for in the models, this approach provides results identical to those of a generalized estimating equation with Poisson regression. To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we performed conditional logistic regressions for only the first flare experienced by 724 gout patients, as well as within-subject pairwise resampling analysis, which adjusts for the correlation issue by using a within-subject matched-set-based resampling technique (23).

To examine the association without the influence of alcohol or purine-rich food intake on the day of gout attacks, we repeated our analyses limited to subjects with no alcohol use and in the lowest quintile of purine intake in the 24 hours prior to attack onset. We also evaluated these effects according to sex, age categories (i.e., 21–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years), body mass index (BMI [<25, 25 to <30, and ≥30 kg/m2]), and use of the following medications in the 24 hours prior to attack onset: diuretics (yes versus no), allopurinol (yes versus no), colchicine (yes versus no), and NSAIDs (yes versus no). We determined the statistical significance of potential subgroup effects by testing the significance of interaction terms added to our final multivariable models. For all ORs, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All P values are 2-sided. We used SAS software, version 9.2 for all analyses.

Results

Our study included 724 gout patients who experienced gout attacks during a 1-year followup period between February 2003 and February 2012. Of the 724 participants, 552 (76.2%) met the ACR preliminary classification criteria for gout. The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The median age of the participants was 54 years. Participants were predominantly men (68%) and white (89%), and more than one-half had received a college education. Subjects were recruited from 49 states and the District of Columbia. Approximately 68% of participants consumed alcohol, 29% used diuretics, 45% took allopurinol, 54% used NSAIDs, and 26% took colchicine during either the hazard or the intercritical periods.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 724 participants in the internet-based case-crossover study of gout*.

| Men | 494 (68.2) |

| Age, median (range) years | 54 (21–88) |

| BMI, median (range) kg/m2 | 30.6 (14.7–69.9) |

| Race | |

| Black | 20 (2.8) |

| White | 642 (88.7) |

| Other | 53 (7.3) |

| Declined to answer | 9 (1.2) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 14 (1.9) |

| High school graduate | 66 (9.1) |

| Some college/technical school | 223 (30.8) |

| College graduate | 175 (24.2) |

| Some professional/graduate school | 78 (10.8) |

| Completed professional or graduate school | 168 (23.2) |

| Household income, dollars | |

| <25,000 | 58 (8.0) |

| 25,000–49,999 | 141 (19.5) |

| 50,000–74,999 | 133 (18.4) |

| 75,000–99,999 | 106 (14.6) |

| ≥100,000 | 186 (25.7) |

| Declined to answer | 100 (13.8) |

| Disease duration, median (range) years | 5 (1–55) |

| Alcohol users | 492 (68.0) |

| Diuretic users | 207 (28.6) |

| Allopurinol users | 329 (45.4) |

| NSAID users | 393 (54.3) |

| Colchicine users | 185 (25.6) |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the number (%).

BMI = body mass index; NSAID = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

During the 1-year followup period, the 724 gout patients experienced a total of 1,433 attacks. Most gout attacks occurred in the lower extremities (92%), particularly in the first metatarsophalangeal joint, and had features of either maximal pain within 24 hours or redness (89%). Approximately 90% of gout attacks were treated with colchicine, NSAIDs, systemic corticosteroids, intraarticular corticosteroid injections, or a combination of these medications. The median time between attack onset and completion of the hazard-period questionnaire was 3 days.

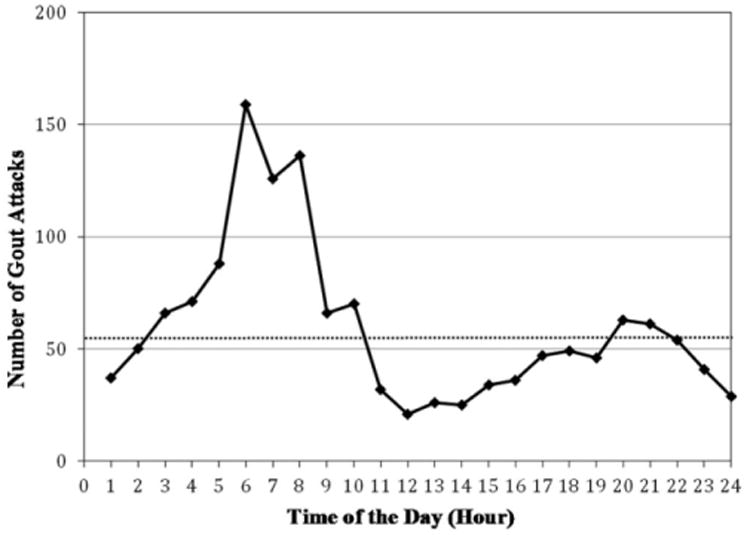

The number of attacks for each hour of the day is displayed in Figure 1. Of the 1,433 attacks, 733, 310, and 390 occurred during the first (i.e., overnight hours), second (i.e., daytime hours), and third (i.e., evening hours) 8-hour time blocks, respectively (Table 2). The risk of gout flares in the first 8 hours of the day (12:00 am to 7:59 am) was 2.36 times higher than in the daytime (8:00 am to 3:59 pm) (OR 2.36 [95% CI 2.05–2.73]). The corresponding OR in the evening (4:00 pm to 11:59 pm) was 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.48). These associations persisted among those with no alcohol use and in the lowest quintile of purine intake in the 24 hours prior to attack onset (Table 3). Furthermore, these associations persisted in subgroups according to diuretic use, and use of allopurinol, colchicine, and NSAIDs during the 24 hours prior to attacks, as well as according to sex, age group, and obesity status (Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Circadian variation of acute gout attacks (n = 1,433). Dotted horizontal line represents the average number of gout attacks per hour (i.e., 60 attacks per hour).

Table 2.

Time of day and risk of gout attacks*

| Time of day, hours | No. of eligible periods | No. of gout attacks | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,433 | 733 | 2.36 (2.05–2.73) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,433 | 310 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,433 | 390 | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) | 0.005 |

OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Table 3. Time of day and risk of gout attacks, by purine intake, alcohol consumption, use of diuretics, and use of antigout drugs over 24 hours prior to gout attack*.

| Risk factors over prior 24 hours, time of day | No. of eligible periods | No. of gout attacks | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purine intake, mg† | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<528) | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 234 | 121 | 2.37 (1.67–3.37) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 234 | 51 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 234 | 62 | 1.22 (0.81–1.82) | 0.35 |

| Quintile 2 (528–731) | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 228 | 130 | 3.33 (2.38–4.67) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 228 | 39 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 228 | 59 | 1.51 (1.02–2.24) | 0.04 |

| Quintile 3 (732–972) | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 269 | 146 | 2.98 (2.17–4.10) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 269 | 49 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 269 | 74 | 1.51 (1.05–2.18) | 0.03 |

| Quintile 4 (973–1,379) | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 313 | 161 | 2.01 (1.52–2.67) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 313 | 80 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 313 | 72 | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) | 0.52 |

| Quintile 5 (> 1,379) | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 389 | 175 | 1.92 (1.49–2.49) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 389 | 91 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 389 | 123 | 1.35 (1.03–1.77) | 0.03 |

| Alcohol intake‡ | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 578 | 320 | 2.78 (2.24–3.45) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 578 | 115 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 578 | 143 | 1.24 (0.98–1.58) | 0.08 |

| No | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 855 | 413 | 2.12 (1.77–2.53) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 855 | 195 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 855 | 247 | 1.27 (1.03–1.55) | 0.02 |

| Diuretic use§ | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 358 | 182 | 2.33 (1.77–3.07) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 358 | 78 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 358 | 98 | 1.26 (0.91–1.73) | 0.17 |

| No | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,075 | 551 | 2.37 (2.01–2.80) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,075 | 232 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,075 | 292 | 1.26 (1.04–1.52) | 0.02 |

| Allopurinol use¶ | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 349 | 163 | 1.90 (1.45–2.47) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 349 | 86 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 349 | 100 | 1.16 (0.86–1.58) | 0.33 |

| No | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,084 | 570 | 2.54 (2.15–3.01) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,084 | 224 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,084 | 290 | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | 0.008 |

| Colchicine use# | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 160 | 86 | 3.31 (2.08–5.27) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 160 | 26 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 160 | 48 | 1.85 (1.10–3.11) | 0.02 |

| No | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,273 | 647 | 2.28 (1.96–2.64) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,273 | 284 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,273 | 342 | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | 0.03 |

| NSAID use** | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 344 | 174 | 2.15 (1.65–2.80) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 344 | 81 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 344 | 89 | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) | 0.57 |

| No | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,089 | 559 | 2.44 (2.07–2.87) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,089 | 229 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,089 | 301 | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 0.003 |

OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; NSAID = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

P for interaction = 0.08.

P for interaction = 0.05.

P for interaction = 0.99.

P for interaction = 0.16.

P for interaction = 0.2608.

P for interaction = 0.59.

Table 4. Time of day and risk of gout attacks, by age, sex, and BMI*.

| Risk factors, time of day | No. of eligible periods | No. of gout attacks | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years† | ||||

| 21–39 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 192 | 100 | 2.63 (1.80–3.84) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 192 | 38 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 192 | 54 | 1.42 (0.90–2.25) | 0.13 |

| 40–49 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 262 | 138 | 2.88 (1.97–4.19) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 262 | 48 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 262 | 76 | 1.58 (1.03–2.44) | 0.04 |

| 50–59 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 477 | 249 | 2.22 (1.74–2.84) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 477 | 112 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 477 | 116 | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | 0.79 |

| 60–83 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | ||||

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 502 | 246 | 2.20 (1.75–2.76) | <0.0001 |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 502 | 112 | Referent | – |

| Sex‡ | 502 | 144 | 1.29 (0.99–1.66) | 0.06 |

| Male | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 1,128 | 585 | 2.45 (2.08–2.87) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 1,128 | 239 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 1,128 | 304 | 1.27 (1.06–1.53) | 0.009 |

| Female | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 305 | 148 | 2.08 (1.54–2.82) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 305 | 71 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 305 | 86 | 1.21 (0.86–1.71) | 0.2770 |

| BMI, kg/m2§ | ||||

| <25 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 123 | 64 | 2.37 (1.46–3.86) | 0.001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 123 | 27 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 123 | 32 | 1.19 (0.70–2.00) | 0.52 |

| 25 to <30 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 501 | 257 | 2.20 (1.72–2.81) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 501 | 117 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 501 | 127 | 1.09 (0.81–1.45) | 0.58 |

| ≥30 | ||||

| 12:00 am to 7:59 am | 809 | 412 | 2.48 (2.06–2.99) | <0.0001 |

| 8:00 am to 3:59 pm | 809 | 166 | Referent | – |

| 4:00 pm to 11:59 pm | 809 | 231 | 1.39 (1.13–1.71) | 0.002 |

BMI = body mass index; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

P for interaction = 0.48.

P for interaction = 0.63.

P for interaction = 0.48.

When we used the subgroup exposure data collected 48 hours prior to attacks, our results did not change materially (see Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.38917/abstract). When we repeated our analysis limited to the first gout flare (n = 724), the ORs were 2.25 (95% CI 1.87-2.70) and 1.20 (95% CI 0.97-1.47) for overnight hours and evening hours, respectively (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 and Supplementary Figure 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.38917/abstract). These ORs remained similar in our within-subject pairwise resampling analyses (23) (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 4, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.38917/abstract).

When we limited the analysis to participants who met the ACR preliminary classification criteria for gout (n = 552), the OR of recurrent gout attacks in the first 8 hours of the day (compared with daytime [8:00 am to 3:59 pm]) was 2.44 (95% CI 2.08-2.87). The corresponding OR in the evening (4:00 pm to 11:59 pm) was 1.36 (95% CI 1.14-1.63). Among those who did not meet the ACR preliminary classification criteria for gout (n = 172), the ORs were 2.09 (95% CI 1.53-2.85) and 0.90 (95% CI 0.64-1.27) for overnight hours and evening hours, respectively. In addition, when we varied the definition of recurrent gout attacks by requiring specific features individually or in combination, the results did not change materially. For example, when we limited the analysis to gout attacks that had at least 2 of the 4 features (i.e., antigout medication use, podagra, maximal pain within 24 hours, and redness) (n = 665), the multivariable ORs were 2.40 (95% CI 2.07-2.80) and 1.27 (95% CI 1.06-1.50) for overnight hours and evening hours, respectively.

Discussion

In this large study of prospectively recruited patients with preexisting gout, we found that the risk of gout attacks during the night and early morning is 2.4 times higher than in the daytime. This association was independent of other risk factors, including time-invariant factors such as genetics, sex, race, and education (by study design), and persisted regardless of the status of time-varying factors such as purine intake, alcohol consumption, and use of antigout medications and diuretics. These findings provide the first prospective evidence of a substantially increased risk of gout attacks during the night and through the early morning hours. These data support the purported mechanisms and historical descriptions of the nocturnal onset of gout attacks and may have implications for the timing of antigout prophylactic measures.

Several potential biologic mechanisms may explain the observed increased risk of gout attacks in the night and early morning hours of the day. Diurnal variation in body temperature ranges from ∼37.5°C between 10:00 am and 6:00 pm to ∼36.4°C between 2:00 am and 6:00 am. As such, the lower body temperature during the early morning hours can potentially lead to a higher risk of UA crystallization, thus triggering gout attacks. Furthermore, relative dehydration during sleep or local (periarticular) dehydration associated with the lying position during sleep has been speculated to contribute to an increased risk of gout attacks at night and through the early morning hours. Diurnal variation of blood cortisol levels, reaching the lowest level at about midnight to 4:00 am, or several hours after sleep onset, may also contribute to nocturnal onset of gout attacks. Of note, the same mechanism has been linked to typical morning stiffness in rheumatoid arthritis patients (i.e., the nocturnal dip in cortisol levels contributing to a decreased “antiinflammatory” milieu and leading to increased inflammatory symptoms in the morning). Indeed, a randomized trial found that use of delayed-release prednisone at night led to substantially more relief of morning stiffness than did conventional immediate-release prednisone use in the morning in rheumatoid arthritis patients (24). Our findings may have similar implications for effective timing of various antigout prophylactic measures. For example, prophylactic drugs for gout flares, particularly those with short half-lives, may be timed appropriately to optimize their benefits.

Another intriguing hypothesis for the typical nocturnal onset is the potential role of sleep apnea (6,7), which is common among obese men with multiple comorbidities, a typical profile of gout patients. For example, 32% of US men with this profile reported having clinically diagnosed sleep apnea in 2005–2006 (25). Hypoxia associated with sleep apnea can enhance nucleotide turnover, thereby generating purines, which are metabolized to UA (8–10). Indeed, up to 50% of sleep apnea patients have been found to have hyperuricemia (11–14), and therefore, sleep apnea could predispose individuals to gout flares, as suggested by a recent cross-sectional study (7). Furthermore, physiologic studies have shown that individuals with sleep-associated hypoxia had an increased ratio of UA excretion to creatinine (Cr) excretion (an indicator of transient UA loading [9]) in the urine overnight, whereas controls with normal sleep study findings showed a decreased ratio of UA excretion to Cr excretion overnight (8). Improvement in sleep apnea–associated hypoxia (with continuous positive airway pressure) was accompanied by a decrease in the overnight change in the ratio of UA excretion to Cr excretion (8).

These findings suggest that nocturnal-onset urate loading could lead to hyperuricemia and gout flares primarily among those with sleep apnea (which can be treated, as shown in hypertension care) (26–28). As sleep apnea is particularly common among those with the typical profile of gout patients and as the associated hypoxia is treatable (e.g., with use of continuous positive airway pressure), clarification of the role of sleep apnea in recurrent gout attacks among gout patients in future studies could add considerably to the effective management of gout.

Several strengths and potential limitations of our study deserve comment. Identifying the onset time for recurrent gout attacks is challenging using conventional study designs. In contrast, our case-crossover study design via the internet was able to trace this varying nature of the risk of gout attacks over each hour of the day in semi–real time, making the hypothesis testing feasible. Furthermore, this study design is highly adaptable to evaluating the effect of a transient exposure as a trigger for acute disease onset, and self-matching of each subject minimizes bias in control selection and removes the confounding effects of the factors that are constant over the study period but differ between participants (e.g., genetic factors, sex, race, education, and BMI status over 1 year) (29). Given the nature of the exposure (hour of the day) collected via the internet in real time (30,31), recall bias in this study is unlikely. Because the time of onset was self-reported, some misclassification of the exact hour may still be possible. However, the exposure classification in our primary analyses using 8-hour time blocks of the day should have minimized such misclassifications.

As discussed above, sleep apnea could play a modifying role in the observed nocturnal onset of gout flares. However, the lack of sleep apnea status data in our existing cohort prohibited the examination of its potential role as an effect modifier (similar to the covariates in Table 4). This topic warrants future studies. Given the nature of our collected data, the timing of NSAID and colchicine use with respect to the timing of the attack leaves undetermined whether temporally these agents materially affect the timing of the attack. Future studies should address these relevant therapeutic issues. Finally, the distribution of purported risk factors among the participants in our study may not be representative of a random sample of US gout patients, but the biologic effects of the time of day on the risk of gout attacks (as reflected in our OR estimates) should be similar.

In conclusion, our study findings provide the first prospective evidence that the risk of gout attacks during the night and early morning is approximately 3 times higher than in the daytime. These data support the purported mechanisms and historical descriptions of the nocturnal onset of gout attacks and may have implications for antigout prophylactic measures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Arthritis Foundation, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the NIH (grant AR-47785).

Dr. Choi has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca and Takeda (less than $10,000 each) and research funding from AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Choi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Choi, Niu, Neogi, Chaisson, Hunter, Zhang.

Acquisition of data. Choi, Neogi, Chen, Chaisson, Hunter, Zhang.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Choi, Niu, Neogi, Zhang.

References

- 1.Khanna D, Khanna PP, FitzGerald JD, Singh MK, Bae S, Neogi T. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: Therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1447–61. doi: 10.1002/acr.21773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. for the National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41. doi: 10.1002/art.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:499–516. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-7-200510040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sydenham T. Corrected from the original Latin by John Pechey in 1711. 7th. London: M. Wellington; 1717. The whole works of that excellent practical physician, Dr. Thomas Sydenham: wherein not only the history and cures of acute diseases are treated of, after a new and accurate method; but also the shortest and safest way of curing most chronical diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams B. High prevalence of gout with sleep apnea. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:349. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roddy E, Muller S, Hayward R, Mallen CD. The association of gout with sleep disorders: a cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasday JD, Grum CM. Nocturnal increase of urinary uric acid: creatinine ratio: a biochemical correlate of sleep-associated hypoxemia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:534–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahebjani H. Changes in urinary uric acid excretion in obstructive sleep apnea before and after therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1998;113:1604–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glantzounis GK, Tsimoyiannis EC, Kappas AM, Galaris DA. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:4145–51. doi: 10.2174/138161205774913255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz Garcia A, Sanchez Armengol A, Luque Crespo E, Garcia Aguilar D, Romero Falcon A, Carmona Bernal C, et al. Blood uric acid levels in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Bronconeumol. 2006;42:492–500. doi: 10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60575-2. In Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plywaczewski R, Bednarek M, Jonczak L, Gorecka D, Sliwinski P. Hyperuricaemia in females with obstructive sleep apnoea. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2006;74:159–65. In Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plywaczewski R, Bednarek M, Jonczak L, Gorecka D, Sliwiniski P. Hyperuricaemia in males with obstructive sleep apnoea (osa) Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2005;73:254–9. In Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou YT, Chuang LP, Li HY, Fu JY, Lin SW, Yang CT, et al. Hyperlipidaemia in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders: prevalence and risk factors. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Chaisson CE, McAlindon T, Woods R, Hunter DJ, Niu J, et al. The online case-crossover study is a novel approach to study triggers for recurrent disease flares. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ, Muller JE for the Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion: protection against triggering by regular exertion. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1677–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yu TF. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1093–103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: twenty-four–hour outcome of the first multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060–8. doi: 10.1002/art.27327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundy JS, Baraf HS, Yood RA, Edwards NL, Gutierrez-Urena SR, Treadwell EL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.So A, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A, Yucel AE, Richard D, Murphy V, et al. Canakinumab for the treatment of acute flares in difficult-to-treat gouty arthritis: results of a multicenter, phase II, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3064–76. doi: 10.1002/art.27600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaffo AL, Schumacher HR, Jr, Saag KG, Taylor WJ, Allison J, Chen L, et al. Developing American College of Rheumatology and European League against Rheumatism criteria for definition of a flare in patients with gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(Suppl 1):S563. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo X, Sorock GS. Analysis of recurrent event data under the case-crossover design with applications to elderly falls. Stat Med. 2008;27:2890–901. doi: 10.1002/sim.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buttgereit F, Doering G, Schaeffler A, Witte S, Sierakowski S, Gromnica-Ihle E, et al. Efficacy of modified-release versus standard prednisone to reduce duration of morning stiffness of the joints in rheumatoid arthritis (CAPRA-1): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:205–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Croft JB, Balluz LS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of self-reported clinically diagnosed sleep apnea according to obesity status in men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006. Prev Med. 2010;51:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepperell JC, Ramdassingh-Dow S, Crosthwaite N, Mullins R, Jenkinson C, Stradling JR, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure after therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised parallel trial. Lancet. 2002;359:204–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbe F, Duran-Cantolla J, Capote F, de la Pena M, Chiner E, Masa JF, et al. Long-term effect of continuous positive airway pressure in hypertensive patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:718–26. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0050OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman D, Loredo JS, Nelesen RA, Ancoli-Israel S, Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure versus supplemental oxygen on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:840–5. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217128.41284.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:144–53. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAlindon T, Formica M, Kabbara K, LaValley M, Lehmer M. Conducting clinical trials over the internet: feasibility study. BMJ. 2003;327:484–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorig KR, Laurent DD, Deyo RA, Marnell ME, Minor MA, Ritter PL. Can a back pain e-mail discussion group improve health status and lower health care costs? A randomized study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:792–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.