Abstract

Background

Substance use and HIV are growing problems in the Mexico-U.S. border city of Tijuana, a sex tourism destination situated on a northbound drug trafficking route. In a previous longitudinal study of injection drug users (IDUs), we found that >90% of incident HIV cases occurred within an ‘HIV incidence hotspot,’ consisting of 2.5-blocks. This study examines behavioral, social, and environmental correlates associated with injecting in this HIV hotspot.

Methods

From 4/06–6/07, IDUs aged ≥18 years were recruited using respondent-driven sampling. Participants underwent antibody testing for HIV and syphilis and interviewer-administered surveys eliciting information on demographics, drug use, sexual behaviors, and socio-environmental influences. Participants were defined as injecting in the hotspot if they most frequently injected within a 3 standard deviational ellipse of the cohort’s incident HIV cases. Logistic regression was used to identify individual and structural factors associated with the HIV ‘hotspot’.

Results

Of 1,031 IDUs, the median age was 36 years; 85% were male; HIV prevalence was 4%. As bivariate analysis indicated different correlates for males and females, models were stratified by sex. Factors independently associated with injecting in the HIV hotspot for male IDUs included homelessness (AOR 1.72; 95%CI 1.14–2.6), greater intra-urban mobility (AOR 3.26; 95% CI 1.67–6.38), deportation (AOR 1.58; 95% CI 1.18–2.12), active syphilis (AOR 3.03; 95%CI 1.63–5.62), needle sharing (AOR 0.57; 95%CI 0.42–0.78), various police interactions, perceived HIV infection risk (AOR 1.52; 95%CI 1.13–2.03), and health insurance status (AOR 0.53; 95%CI 0.33–0.87). For female IDUs, significant factors included sex work (AOR 8.2; 95%CI 2.2–30.59), lifetime syphilis exposure (AOR 2.73; 95%CI 1.08–6.93), injecting inside (AOR 5.26; 95%CI 1.54–17.92), arrests for sterile syringe possession (AOR 4.87; 95%CI 1.56–15.15), prior HIV testing (AOR 2.45; 95%CI 1.04–5.81), and health insurance status (AOR 0.12; 95%CI 0.03–0.59).

Conclusion

While drug and sex risks were common among IDUs overall, policing practices, STIs, mobility, and lack of healthcare access were correlated with injecting in this HIV transmission hotspot. Although participants in the hotspot were more aware of HIV risks and less likely to report needle sharing, interventions addressing STIs and structural vulnerabilities may be needed to effectively address HIV risk.

Keywords: injection drug use, HIV, Tijuana, transmission hotspot, mobility, female sex work

Introduction

Tijuana, a Mexican city of 1.6 million people, has experienced rising HIV prevalence in vulnerable groups over the past decade (Strathdee & Magis-Rodriguez, 2008). Located on the Mexico-U.S. border, adjacent to San Diego, Tijuana is on a major drug trafficking route whereby heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine are transported to the United States (Bucardo et al., 2005). Of all Mexican cities, Tijuana has the highest number of drug users per capita and an estimated 10,000 injecting drug users (IDUs) (Strathdee et al., 2005). Past modeling of the HIV epidemic in Tijuana revealed that one in every 116 people aged 15–49 years are living with HIV, and that the epidemic is concentrated in certain at-risk groups, including IDUs (Iniguez-Stevens et al., 2009). However, the HIV epidemic is not homogeneous among IDU. Findings by Strathdee and colleagues indicate that HIV prevalence differs significantly by sex (3.5% vs 10.2% among male and female IDUs, respectively) (Strathdee et al., 2008).

In a recent paper, we reported that almost all (>90%) of the incident HIV cases among a cohort of Tijuana IDUs (followed for 18 months) had injected within a 2.5 block radius of each other in the study visit immediately prior to seroconversion (Brouwer, Rusch, et al., 2012). This strong clustering of incident HIV cases overlapped with and largely encompassed Tijuana’s red light district or ‘Zona Roja,’ which is well known for its sex tourism. The Zona Roja is made up of several blocks within a neighborhood abutting the main Mexico/US border crossing, although it is difficult to define the exact size of the area as the outer edges are fluid. Within this sex work tolerance zone, prostitution is quasi-legal as long as sex workers obtain a permit requiring monthly HIV testing and quarterly screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Sirotin et al., 2010). Cost (approximately $360/year) and fear of testing HIV positive are main reasons why many sex workers (>50%) operate without a permit (Bucardo et al., 2004).

While police stations are spread throughout Tijuana, the area around the HIV hotspot is heavily patrolled. Police interactions have been associated with risky injection practices (i.e. rushed injection, needle sharing, utilization of shooting galleries) among IDUs in this and other cities (Rachlis et al., 2010)Cooper et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2008; Pollini et al., 2008). Counter balancing this, harm reduction services, including needle exchange, are also concentrated in this area, with mobile clinics serving distant neighborhoods.

Another factor featuring prominently in the risk environment of Tijuana is mobility. IDU populations are known to be highly mobile, traveling within cities and across international borders in search of work and safety, to escape social controls, and to access illicit drugs (Rachlis et al., 2007). In a recent study, we found that approximately 25% of IDUs in Tijuana regularly travel ≥3km between residence and injection site and 18% had crossed the Mexico-U.S. border in the past 6 months (Brouwer, Lozada, et al., 2012). Intra-urban and cross-border mobility may be a factor in transmission of HIV because IDUs who travel are connecting to, and may be engaging in high-risk behaviors, with individuals in different sexual and drug use networks.

The present analysis examines a variety of individual and contextual determinants thought to be associated with injecting within the HIV incidence ‘hotspot.’ We hypothesized that 1) IDUs who inject in the hotspot are likely to have traveled farther from their place of residence compared to those who inject outside the hotspot; and 2) the geographical overlap of the ‘hotspot’ with the red light district may be associated with increased probability that IDUs primarily injecting in this area were more likely to engage in commercial sex (i.e. purchasing or selling sexual services) and/or to have experienced a rushed injection because of the increased police presence (i.e. more frequent patrols) within the Zona Roja. Thus, in this manuscript we explore the association between drug injection location and risk behaviors in order to understand factors that might be influencing HIV transmission in this area compared to other parts of Tijuana.

Methods

Study Population

Between April 2006 and April 2007, 1,056 IDUs living in Tijuana were recruited into a prospective study of factors associated with HIV, syphilis, and tuberculosis (TB) infections (Proyecto El Cuete, Phase III). Eligibility criteria were being at least 18 years of age, injecting illicit drugs within the previous month (confirmed by inspection of injection track marks), ability to speak English or Spanish, and reporting no plans to permanently move away from Tijuana within the next 18 months. Using respondent-driven sampling (RDS), a group of “seeds” was initially selected based on diversity of neighborhoods, gender, age, and drug preferences (Heckathorn, 1997). Seeds were then given recruitment coupons to refer up to three peers to the study and additional waves of recruitment continued until the sample size was reached. Participants received monetary compensation for their time of approximately $10 US dollar to complete the baseline interview and also $5 for each eligible male recruit or $6 for each eligible female recruit that they referred. They received more money for female recruits because networks of female IDUs are more difficult to access in this city than male IDUs.

Data Collection and Laboratory Testing

Initial recruitment of seeds and subsequent interviews were conducted by local outreach workers in a mobile office in a modified recreational vehicle and a storefront office. At baseline and each six month follow-up, participants completed an interviewer-administered survey eliciting information on sociodemographic, behavioral, and contextual characteristics related to drug use and sexual behaviors occurring over their lifetime and within the past six months. Additional domains included HIV knowledge, incarceration history, and health care utilization. For this study analysis, only the baseline data was used, thus the analysis is cross-sectional. During study visits, locations where participants live (or most often sleep at night), work/earn money, obtain drugs, and inject drugs were plotted on paper-maps, with the interviewers helping to narrow down locations from colonias (or neighborhoods) to more precise locations based on a discussion of landmarks and major crossroads. Geosptaial data were later digitized in ArcMap 9.3 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) (Brouwer, Rusch, et al., 2012). Verbal and written consent was sought from all participants and the study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, San Diego and the Ethics Committee of the Tijuana General Hospital.

The ‘Determine’ rapid HIV antibody test (Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Boston, MA) was administered to detect the presence of HIV antibodies. All reactive samples were confirmed using an HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay and immunofluorescence assay. Syphilis serology used the rapid plasma regain (RPR) test (Macro-Vue; Becton Dickenson, Cockeysville, MD). RPR-positive samples were subjected to confirmatory testing using the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA; Fujirebio, Wilmington, DE). Syphilis titers ≥ 1:8 were considered to be consistent with active infection, whereas the remainder of positive specimens was considered to reflect lifetime, rather than current infection. Specimen testing was conducted by the San Diego County Health Department. Participants testing positive for syphilis were treated on site and those testing positive for HIV or TB were referred to the Tijuana municipal health clinic for free follow-up care.

Variable Definitions

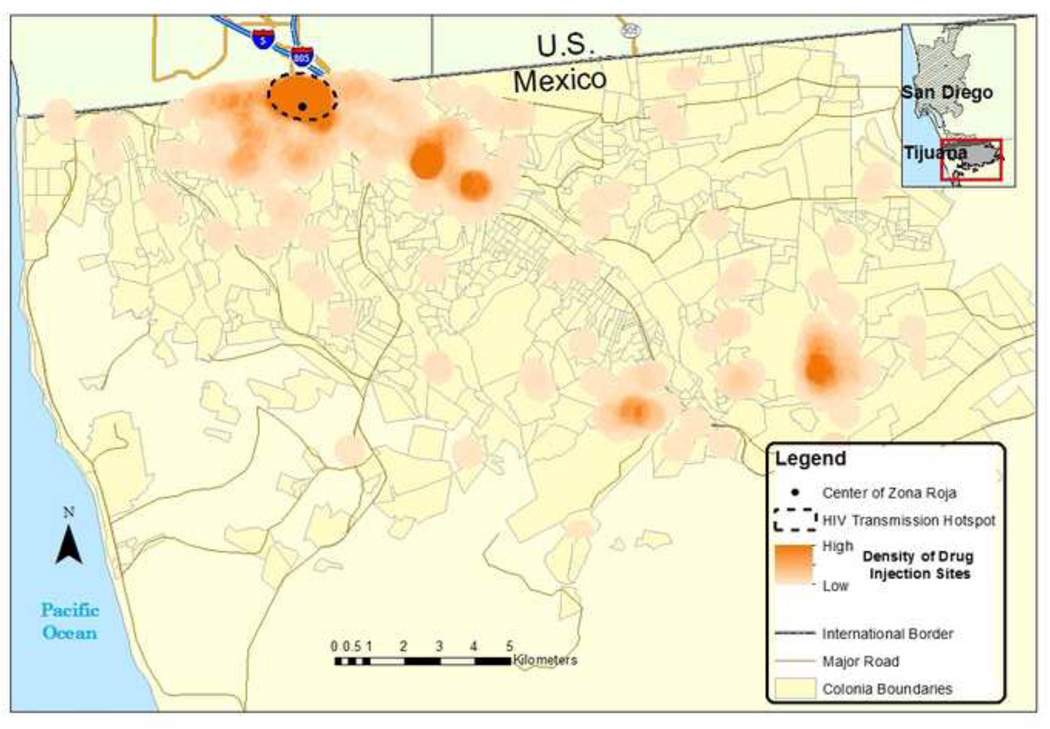

Participants were defined as injecting in the HIV incidence ‘hotspot, an area of approximately 1.95 square kilometers’ if they most frequently injected within a three standard deviational ellipse of the cohort’s incident HIV cases (Figure 1). Participants were asked, “In the past 3 months, where did you shoot up the most often?” and their responses were mapped to capture the location where they most frequently injected drugs. The HIV hotspot abuts the busy San Ysidro Mexico/US border crossing and overlaps Tijuana’s most well-known red light district (Zona Roja in Spanish). All variables used in this analysis were dichotomized with the exception of age, age at first injection, and number of personal contacts who have died from AIDS, which were left continuous. Educational level was divided by secondary education or higher (at least 9th grade) vs. less than a secondary education because this is the level to which education is compulsory in Mexico. Homelessness was defined as sleeping in a car, abandoned building, shelter, shooting gallery, or on the streets. If participants answered that they speak “fluent/native,” “very well,” or “ok” English on the questionnaire, then they were defined as speaking “some English.”

Figure 1.

Location of HIV incidence hotspot in relation to density of drug injection sites in Tijuana, Mexico

Statistical Analysis

Only participants who provided mappable data for the location where they most frequently injected drugs were included in the present study (n=1031/1056). Group comparisons were assessed using Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables and nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Binary logistic regression was used to assess predictors of injecting in the HIV ‘hotspot.’ Bivariate analyses were first conducted to determine individual, social, and environmental correlates. During this step, we found different correlates by sex, so we created separate models for male and female IDUs. Correlation statistics were run between the independent variables to check for collinearity before running the multivariate logistic regression. Variables with significance P≤0.10 were considered for inclusion in the multivariate regression model. Forward stepwise procedures were then performed to determine which predictors remained in the final, reduced model for both men and women using P<0.05 as the cutoff. A backward stepwise approach was also used to confirm the forward, model-building results which reached the same final model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS v9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

The median age of the 1,031 participants included in the present analysis was 36 years; 85% were male; and 13% were homeless in the past six months. The most frequently injected drugs in the past 6 months were heroin alone (57%) and methamphetamine and heroin mixed (40%), and did not differ significantly by injection location. Although the HIV transmission hotspot was small (1.95 square kilometers), substance use was highly concentrated in this area with nearly half (48%) of participants reporting most often injecting drugs within the hotspot. Compared to those injecting outside the HIV hotspot, a greater proportion injecting within the HIV hotspot were female (21% vs. 9%); reported sex work as their principal source of income in the past year (P<0.001); traveled >5km between where they live and inject (P=0.006); had ever been deported from the U.S. (P=0.001); and had lifetime or active syphilis infection (P<0.001) (Table 1). Interactions with police featured prominently in the hotspot, with a higher proportion of IDUs in the HIV hotspot reporting police affecting injection practices, getting arrested for carrying unused needles/syringes, being beaten by police, or having their syringes taken by police in the past six months. Those injecting inside the hotspot had higher perceived risk of getting HIV compared to those injecting outside this area (P=0.005), and they more often engaged in risky sexual behaviors such as sex work, unprotected sex, and being under the influence of drugs during sex.

Table 1.

Characteristics of IDUs who inject inside versus outside the HIV infection hotspot in Tijuana, Mexico, April 2006-April 2007

| OVERALL (n=1031) |

MALES (n=880) |

FEMALES (n=151) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hotspot (n=490) |

Outside Hotspot (n=541) |

P- value |

Hotspot (n=387) |

Outside Hotspot (n=493) |

P- value |

Hotspot (n=103) |

Outside Hotspot (n=48) |

P- value |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Age - Median (Inter-quartile range (IQR)) | 35 (30–41) | 37 (31–42) | 0.105 | 36 (31–42) | 37 (31–42) | 0.511 | 34 (28–39) | 36 (26–42) | 0.363 |

| Married/Common law | 34.5% | 28.8% | 0.051 | 30.2% | 27% | 0.288 | 50.5% | 47.9% | 0.769 |

| <9th grade education | 42.5% | 40.5% | 0.523 | 41.3% | 39.8% | 0.634 | 46.6% | 47.9% | 0.880 |

| Homeless (past 6 mo) | 15.5% | 10.7% | 0.022 | 18.9% | 11.0% | <0.001 | 2.9% | 8.3% | 0.140 |

| Speak some English | 32.2% | 29.9% | 0.425 | 32.0% | 29.6% | 0.439 | 33.0% | 33.3% | 0.969 |

| Prostitution was main source of income in past year | 8.4% | 1.67% | 0.009 | 0.78% | 1.01% | 0.714 | 36.9% | 8.3% | <0.001 |

| Had health insurance (past 6 mo) | 7.4% | 12.2% | <0.001 | 8.3% | 12.2% | 0.060 | 3.9% | 12.5% | 0.047 |

| Mobility | |||||||||

| Travels >5km between residence and regular injection site | 6.4% | 2.8% | 0.006 | 7.4% | 3.1% | 0.004 | 2.9% | 0% | 0.232 |

| Moved to Tijuana in the past 5 years | 25.9% | 20.9% | 0.056 | 26.6% | 20.5% | 0.033 | 23.3% | 25.0% | 0.820 |

| Ever deported from the U.S. | 43.8% | 34.0% | 0.001 | 49.1% | 35.5% | <0.001 | 23.5% | 18.8% | 0.510 |

| Crossed US-Mexico border in the past year | 7.1% | 6.5% | 0.668 | 5.4% | 6.1% | 0.678 | 13.6% | 10.4% | 0.584 |

| Clinical Status | |||||||||

| Active syphilis (antibody titer≥1:8) | 11.5% | 4.3% | <0.001 | 9.3% | 3.7% | <0.001 | 19.8% | 11.1% | 0.198 |

| Lifetime syphilis exposure (antibody positive) | 22.4% | 9.5% | <0.001 | 16.6% | 8.1% | <0.001 | 44.6% | 24.4% | 0.021 |

| HIV positive | 6.7% | 1.67% | <0.001 | 5.4% | 1.83% | 0.004 | 11.7% | 0% | 0.015 |

| Drug Use Risk Behaviors (last 6 months, unless indicated) | |||||||||

| Age at first injection - Median (IQR) | 20 (16–25) | 20 (17–25) | 0.974 | 20 (16–25) | 20 (16–25) | 0.861 | 20 (17–24) | 20 (17–27.5) | 0.517 |

| Ever injected with someone who lives in the U.S. | 49.2% | 46.2% | 0.340 | 53.5% | 47.5% | 0.076 | 33.0% | 33.3% | 0.970 |

| Receptive needle/syringe sharing | 53.5% | 63.2% | 0.002 | 55.8% | 64.9% | 0.006 | 44.7% | 45.8% | 0.893 |

| Distributive needle/syringe sharing | 58.2% | 63.8% | 0.065 | 60.2% | 64.7% | 0.171 | 50.5% | 54.2% | 0.673 |

| Injects more than once a day | 82.6% | 83.4% | 0.726 | 83.8% | 83.4% | 0.873 | 78.0% | 83.7% | 0.435 |

| Normally injected drugs outside | 38.4% | 38.1% | 0.924 | 46.5% | 39.6% | 0.038 | 92.2% | 77.1% | 0.009 |

| Aware of needle exchange program in the area | 33.7% | 15.5% | <0.001 | 31.8% | 15.8% | <0.001 | 40.8% | 12.5% | <0.001 |

| Used needle exchange program | 26.9% | 8.3% | <0.001 | 26.6% | 8.3% | <0.001 | 28.2% | 8.3% | 0.006 |

| Encounters with Police | |||||||||

| Police presence ever caused a rushed injection | 36.7% | 30.5% | 0.034 | 37.7% | 31.6% | 0.059 | 33.0% | 18.8% | 0.071 |

| Police presence affected where used drugs (past 6 mo) | 44.6% | 36.3% | 0.007 | 46.1% | 37.2% | 0.008 | 38.8% | 27.1% | 0.159 |

| Police presence affected new syringe access (past 6 mo) | 13.5% | 11.3% | 0.289 | 14.5% | 11.6% | 0.203 | 9.7% | 8.3% | 0.786 |

| Arrested for any reason (past 6 mo) | 78.2% | 73.2% | 0.064 | 82.2% | 75.7% | 0.0196 | 63.1% | 47.9% | 0.078 |

| Ever arrested for carrying unused needles/sterile | 37.6% | 31.2% | 0.033 | 38.5% | 32.7% | 0.072 | 34.0% | 16.7% | 0.028 |

| Arrested for carrying unused needles/syringes (past 6 mo) | 31.6% | 25.3% | 0.025 | 34.6% | 26.6% | 0.010 | 20.4% | 12.5% | 0.239 |

| Arrested for carrying used needles/syringes (past 6 mo) | 32.7% | 31.4% | 0.673 | 37% | 32.9% | 0.206 | 16.5% | 16.7% | 0.980 |

| Arrested for having track marks (past 6 mo) | 46.3% | 44.0% | 0.452 | 49.9% | 46.0) | 0.259 | 33.0% | 22.9% | 0.207 |

| Beaten by police (past 6 mo) | 40.4% | 32.4% | 0.007 | 44.7% | 34.3% | 0.002 | 24.3% | 12.5% | 0.095 |

| Ever sexually assaulted by police officer | 7.5% | 2.6% | <0.001 | 1.09% | 0.43% | 0.261 | 31.3% | 25.6% | 0.492 |

| Sexually assaulted by police (past 6 mo) | 3.1% | 0.74% | 0.006 | 0.78% | 0% | 0.050 | 11.7% | 8.3% | 0.537 |

| Police officer ever ask for sexual favors | 11.2% | 3.1% | <0.001 | 0.48% | 0.48% | 0.731 | 48.5% | 27.9% | 0.023 |

| Asked for sexual favors by police (past 6 mo) | 5.3% | 1.66% | 0.001 | 0.52% | 0.41% | 0.808 | 23.3% | 14.6% | 0.217 |

| Syringes taken by police (past 6 mo) | 9.6% | 5.6% | 0.014 | 9.8% | 5.7% | 0.021 | 8.7% | 4.2% | 0.314 |

| HIV Knowledge | |||||||||

| High perceived risk of HIV infection | 49.2% | 40.3% | 0.005 | 52.0% | 41.2% | 0.002 | 38.8% | 31.3% | 0.367 |

| Ever had HIV test | 45.1% | 37.0% | 0.008 | 38.0% | 35.3% | 0.411 | 71.8% | 54.2% | 0.032 |

| Knows anyone personally who has HIV/AIDS | 46.1% | 34.2% | <0.001 | 45.2% | 34.9% | 0.002 | 49.5% | 27.1% | 0.009 |

| Median number of personal contacts who died from AIDS (IQR) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0.002 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||||||

| Sexually active (past 6 mo) | 30.7% | 22.9% | 0.005 | 10.6% | 22.1% | 0.501 | 56.4% | 31.3% | 0.004 |

| Men who had ever had sex with men (n=880) | 27.7% | 24.3% | 0.266 | 27.7% | 24.3% | 0.266 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ever traded sex in exchange for money or goods | 27.0% | 18.7% | 0.002 | 18.1% | 16.4% | 0.517 | 61.6% | 41.7% | 0.023 |

| Did not use condom with casual partner (past 6 mo) | 11.4% | 7.4% | 0.026 | 10.3% | 7.7% | 0.173 | 15.5% | 4.2% | 0.045 |

| Used drugs within 2 hours before or during sex with casual partner (past 6 mo) | 20.0% | 12.0% | 0.014 | 15.0% | 11.6% | 0.135 | 38.8% | 16.7% | 0.006 |

| Ever forced to have sex | 6.8% | 3.1% | 0.007 | 0.78% | 1.22% | 0.518 | 29.7% | 22.9% | 0.386 |

Notes: Overall n: n=1016 for travels >5km; n=974 for ever sexually assaulted by police, and ever asked for sexual favors; n=1015 for high perceived risk of HIV infection; Total n for males: n=832 for sexual assault by police, and sexual favors by police; n=865 for traveling >5km; n=864 for high perceived risk of HIV; n=857 for inject more than once a day

Of the 490 IDUs who reported regularly injecting drugs within the HIV incidence hotspot, 6.7% were HIV positive (vs. 1.67% outside of this area). Harm reduction services in Tijuana are particularly focused in this area and are reflected by higher awareness (34% vs. 16%) of needle exchange services and utilization of these services (27% vs. 8%) in the hotspot compared to outside of the area (Table 1). Forty-six percent of IDUs in the hotspot had known someone personally who has HIV/AIDS and several knew as many as 50 people (vs. 20 outside the hotspot) who had died of AIDS. Because these variables are closely linked to the definition of the HIV incidence hotspot and the availability of services in them they were not included in the multivariate model.

As depicted in Table 1, the characteristics of IDUs who injected inside versus outside the HIV incidence hotspot in Tijuana suggested differences by sex. Thus, bivariate analyses were performed separately for males and females (see Table 2). Compared with men injecting outside of the hotspot, men injecting inside the HIV incidence hotspot were 1.89 and 1.75 times as likely to be homeless or a deportee, respectively (P<0.001). They also had increased odds of having syphilis (P<0.001), having higher perceived risk of acquiring HIV (P=0.001), and injecting outdoors (P=0.04), with marginally higher odds of having rushed injection due to police presence (P=0.06).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations with injecting in an HIV infection hotspot among male and female IDUs in Tijuana, Mexico, April 2006–April 2007

| Variables | Males (n= 880) Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Females (n= 151) Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) |

| Married/Common Law | 1.17 (0.87–1.57) | 1.11 (0.56–2.20) |

| <9th grade education | 1.07 (0.82–1.40) | 0.95 (0.48–1.88) |

| Homeless (past 6 mo) | 1.89 (1.29–2.77)*** | 0.33 (0.07–1.54) |

| Speaks some English | 1.12 (0.84–1.50) | 0.99 (0.48–2.04) |

| Prostitution was main source of income in past year | 0.76 (0.18–3.22) | 6.43 (2.14–19.30)*** |

| Had health insurance (past 6 mo) | 0.65 (0.41–1.02)* | 0.28 (0.08–1.05)* |

| Mobility | ||

| Travels > 5km between residence and regular injection site | 2.48 (1.31–4.71)*** | >999 (<0.01–>999) |

| Moved to Tijuana in the past 5 years | 1.41 (1.03–1.93)** | 0.91 (0.41–2.02) |

| Ever deported from the U.S. | 1.75 (1.34–2.30)*** | 1.33 (0.57–3.14) |

| Clinical Status | ||

| Active syphilis (antibody titer≥1:8) | 2.71 (1.51–4.85)*** | 1.98 (0.69–5.65) |

| Lifetime syphilis exposure (antibody positive) | 2.25 (1.48–3.42)*** | 2.48 (1.13–5.45)** |

| Drug Use Risk Behaviors (past 6 months, unless indicated) | ||

| Ever injected with someone who lives in the U.S. | 1.27 (0.98–1.66)* | 0.99 (0.48–2.04) |

| Receptive needle/syringe sharing | 0.68 (0.52–0.90)*** | 0.96 (0.48–1.90) |

| Normally injected drugs outdoors for males/ indoors for females | 1.33 (1.02–1.74)** | 3.53 (1.32–9.47)** |

| Encounters with Police | ||

| Police presence ever caused a rushed injection | 1.31 (0.99–1.73)* | 2.14 (0.93–4.91)* |

| Police presence affected where used drugs (past 6 mo) | 1.45 (1.10–1.90)*** | 1.71 (0.81–3.62) |

| Arrested for any reason (past 6 mo) | 1.48 (1.06–2.07)** | 1.86 (0.93–3.72)* |

| Ever arrested for carrying unused needles/sterile | 1.29 (0.98–1.71)* | 2.57 (1.09–6.09)** |

| Arrested for carrying unused/sterile needles/syringes (past 6 mo) | 1.46 (1.10–2.00)*** | 1.79 (0.67–4.78) |

| Beaten by police (past 6 mo) | 1.55 (1.18–2.04)*** | 2.24 (0.85–5.90) |

| Police officer ever ask for sexual favors | 1.28 (0.32–5.14) | 2.43 (1.12–5.27)** |

| Syringes taken by police (past 6 mo) | 1.81 (1.09–3.00)** | 2.20 (0.46–10.6) |

| HIV Knowledge | ||

| High perceived risk of HIV infection | 1.54 (1.18–2.02)*** | 1.40 (0.68–2.89) |

| Ever had HIV test | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | 2.16 (1.06–4.40)** |

| Sexual Behavior (past 6 months, unless indicated) | ||

| Sexually active | 1.11 (0.81–1.53) | 2.85 (1.38–5.89)*** |

| Ever traded sex in exchange for money or goods | 1.12 (0.79–1.60) | 2.25 (1.11–4.54)** |

| Did not use condom with casual partner | 1.38 (0.87–2.20) | 4.23 (0.93–19.2)* |

| Used drugs within 2 hours before or during sex with casual partner | 1.35 (0.91–2.00) | 3.18 (1.35–7.47)*** |

Notes: Males: Total n=832 for sexual assault by police; n=832 for sexual favors by police; n=865 for traveling >5km; n=864 for high perceived risk of HIV; n=857 for inject more than once a day

p-value≤0.10

p-value<0.05

p-value<0.01

Compared to female IDUs injecting outside the hotspot, those who injected within the hotspot had 6.43 times the odds of reporting prostitution as their principal income in the past year (P<0.001), were 2.48 times as likely to have lifetime exposure to syphilis (P=0.02), 2.16 times more likely to have been tested for HIV before this study (P=0.03), and 2.43 times more likely to ever have been asked for sexual favors by police (P=0.02); 3.53 times more likely to inject inside home (P=0.01); and 4.23 times more likely to have engaged in casual sex with no condom use in the past six months (P=0.06).

Correlates of Injecting in the HIV Incidence Hotspot

Separate multivariate models were constructed for men and women. In the final multivariate model for men (Table 3), independent correlates of injecting in the HIV incidence hotspot included 3.03 times greater odds of having an active syphilis infection and 1.72 and 1.58 times greater odds of being homeless or ever being deported from the U.S., respectively. Men who injected in the hotspot also had 3.26 times the odds of having traveled farther between their residence and their regular injection location (95% CI 1.67–6.38) and were 1.52 times more likely to have high perceived risk of HIV infection (95% CI 1.13–2.03). Police interaction variables were also significant correlates of injection in the hotspot. Interestingly, men who injected inside the HIV hotspot had decreased odds of engaging in receptive needle/syringe sharing than those outside of the hotspot (P<0.001) and were also less likely to have had health insurance in past six months compared to injectors outside of the hotspot (P=0.01).

Table 3.

Factors independently associated with an HIV infection hotspot among male and female IDUs in Tijuana, Mexico, April 2006–April 2007

| Independent Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio for Males (95% CI) (n=845) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Females (95% CI) (n=146) |

|---|---|---|

| Homeless (past 6 months) | 1.72 (1.14–2.60)** | |

| Travels > 5km between residence and regular injection site | 3.26 (1.67–6.38)*** | |

| Ever deported from the U.S. | 1.58 (1.18–2.12)** | |

| Active syphilis (syphilis titer≥1:8) | 3.03 (1.63–5.62)*** | |

| Receptive needle/syringe sharing (past 6 mo) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78)*** | |

| Police presence affected where used drugs (past 6 mo) | 1.59 (1.17–2.15)** | |

| Beaten by police officer (past 6 mo) | 1.57 (1.17–2.11)** | |

| High perceived risk of HIV infection | 1.52 (1.13–2.03)** | |

| Had health insurance (past 6 mo) | 0.53 (0.33–0.87)* | 0.12 (0.03–0.59)** |

| Prostitution was main source of income in past year | 8.20 (2.20–30.59)** | |

| Lifetime syphilis exposure (antibody positive) | 2.73 (1.08–6.93)* | |

| Normally injects indoors (past 6 mo) | 5.26 (1.54–17.92)** | |

| Ever arrested for carrying unused needle/syringe | 4.87 (1.56–15.15)** | |

| Ever had HIV test | 2.45 (1.04–5.81)* |

p-value<0.05

p-value<0.01

p-value<0.001

In the final multivariable model for women (Table 3), female IDUs who injected in the HIV incidence hotspot were 8.2 times more likely to report prostitution as main source of income in the past year (P=0.001), 5.26 times more likely to regularly inject drugs indoors (P=0.008) and 4.87 times more likely to have ever been arrested for carrying unused needles/syringes (P=0.006). They also had nearly 2.73 times greater odds of testing positive for syphilis antibodies (P=0.03) and 2.45 times more likely to have been tested for HIV in the past (P=0.04). Similar to male IDUs, female IDUs in the hotspot were much less likely to have had health insurance in past six months (P=0.008).

Discussion

In this study of an area of high HIV incidence in Tijuana, we found that there were significant differences among IDUs who regularly inject in the HIV hotspot compared to those who primarily inject outside of the hotspot. We also found different correlates of injecting in this HIV hotspot between male and female injectors. These findings provide insight into potentially modifiable factors that may be associated with increased HIV transmission in this area.

As hypothesized, mobility was statistically significantly associated with injecting in the HIV hotspot, although this was only true for male, not female IDUs. Among male study participants, those in the hotspot had higher odds of reporting ever being deported from the U.S. and traveling a sizeable distance (>5km) between where they live and regularly inject. This finding may have important implications for disease transmission. Studies elsewhere have shown how mobility can potentially increase risk of HIV transmission through such factors as the social changes associated with migration, bridging of social networks, disconnection with health services, and increased exposure to authorities - which might lead to risky injection practices, such as rushed injections or needle sharing (Atlani, 2000; Deren, 2003; Elliot, 2003; Rachlis, et al., 2007). Maas et al found that mobility was a significant factor in HIV infection among IDUs in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. They observed IDUs’ movements both into and out of the Downtown Eastside due to drug availability, affordable housing, and sex trade work (Maas et al., 2007). Tijuana is a major repatriation point for Mexicans who are deported from the U.S.; 39% of our total sample and 44% of men primarily injecting in the HIV hotspot had ever been deported. Deportation may predispose IDUs to HIV risk behaviors by separating them from their social networks and employment, and triggering a cycle of homelessness (Strathdee, et al., 2008). A previous study by our group found that individuals who had been deported were less knowledgeable about HIV risks and less likely to have been tested for HIV compared to non-deportees (Brouwer et al., 2009). Deportation has increased steadily over the past decade (US Department of Homeland Security, 2013), which may have unintended consequences for public health in Tijuana and other repatriation sites, especially among groups vulnerable to HIV and other infectious diseases, such as IDUs.

Male IDUs primarily injecting in the hotspot were also more likely to report having been beaten, arrested for carrying unused syringes, or otherwise affected by police presence. Even though possession of sterile syringes without a prescription is legal in Mexico, police enforcement does not always reflect laws on the books and instead may be having a negative impact on IDUs’ ability to perform safe injection practices. Studies have shown that fear of arrest discourages IDUs from purchasing and carrying sterile syringes, and may lead to rushed injection practices that include sharing syringes/other injection paraphernalia, even in settings where over-the-counter syringe sales and possession are legal (Miller, et al., 2008; Pollini et al., 2008). A study in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside found that IDUs who reported public injection and who were affected by police presence more often engaged in high-risk injection practices, such as rushed injection (Rachlis, et al., 2010). Furthermore, aggressive policing practices and legal repressiveness have been associated with shooting gallery utilization (Cooper, et al., 2011) and HIV prevalence among IDUs in a variety of settings (Friedman et al., 2006).

Female IDUs in the hotspot were more likely to report injecting indoors compared to women primarily injecting outside of the hotspot. An indoor setting might reflect drug use associated with sex work; in our bivariate analysis, for women there was a strong association between injecting in the hotspot and drug use before or during sex. Further, while assessing collinearity between variables before constructing the multivariate model, we found there was a high correlation between sex work and drug use before or during sex (data not shown). As we hypothesized, sex work was highly associated with injecting in the HIV hotspot for female IDUs, which suggests that the combination of both drug use and sexual risks, associated with sex work, may be driving HIV incidence among females in our sample. This conclusion is substantiated by several studies documenting higher rates of HIV among injection drug using female sex workers (FSWs) compared to non-injecting FSWs or IDUs alone (Patterson et al., 2008; Strathdee, et al., 2008).

Numerous studies indicate that needle sharing increases risk of HIV transmission, including our previous work in this area which found a correlation between number of injection partners and HIV (Strathdee, et al., 2008); however, in this present analysis, we found that needle sharing was lower among those injecting in the HIV hotspot. This finding may be attributable to social desirability response bias; individuals in the hotspot were more likely to be exposed to harm reduction services, and knowing needle sharing is a risk factor for HIV transmission, these individuals may have been more likely to underreport needle sharing. However, these participants who most frequently injected inside the hotspot were also more likely to have used syringe exchange programs (SEPs) compared to those who inject outside the hotspot, reported knowing more people with HIV or who have died of AIDS, and had higher perceived risk of acquiring HIV. Thus, it could be that participating in harm reduction services, which are more available within than outside the hotspot, is having a beneficial impact by increasing awareness about transmission of HIV and reducing needle sharing.

We also found that fewer male and female IDUs in the hotspot had health insurance in the past six months compared to injectors outside the hotspot. Depending on a person’s job status, medical care in Mexico is either subsidized fully or in part by the federal government. Mexico aspires to universal health coverage for all its citizens; therefore, even the poorest can obtain insurance through Seguro Popular, a government funded healthcare program. However, to sign up for this insurance, proper identification showing citizenship must be presented – posing a barrier to some migrants and especially to deportees – which were over-represented in the HIV transmission hotspot.

There are several limitations to this study. Because we were not exploring predictors of HIV infection, but rather correlates of injecting in a high transmission area, we cannot conclude that the specific variables found to be associated with injection in the hotspot were directly related to HIV transmission; we can only speak about a geographical association with a high transmission area. Also, this analysis focused on the locations where a participant “most often” injected drugs in the past three months. Thus, our data fails to capture activities of participants who often move injection sites or inject in a variety of locations. Despite using respondent-driven sampling to try to obtain a less biased sample, some social networks may have been overrepresented while others underrepresented. Participants were given a small monetary reimbursement for their participation in the study and, for some social groups (e.g. those with high income, those with higher social status that may not want to be linked to the study), the reimbursement may not have been enough of an incentive to spend the time needed for full participation in the study. Also, as mentioned earlier, self-presentation bias may have led some participants to over- or underestimate health/risk behaviors in order to provide more socially desirable responses. In regards to analysis, because we investigated a large number of variables, it is possible that some of the associations found were due to chance alone (type I error). However, multivariate modeling likely removed spurious associations, especially considering that most of the variables in the final model were strongly associated with injection in the hotspot (p-value<0.01) and supported prior literature related to HIV infection or HIV risk behaviors. Finally, our analysis may have been limited by not measuring other factors that could have given better insight into injection in the hotspot.

At the local level, our findings have important implications for organizations working in HIV prevention and harm reduction for individuals who inject drugs in Tijuana and more specifically within this HIV incidence area that abuts the ‘Zona Roja.’ For women, injecting in the hotspot was predicted by injecting indoors, lifetime syphilis infection, being arrested for carrying paraphernalia, ever being tested for HIV and sex work. Women injecting primarily in the hotspot were over 4-fold more likely to report prostitution as their main source of income. This risk factor may underlie predictors for these female IDU as 1) sex workers are disproportionately vulnerable to STI because of the increased likelihood they will engage in multiple concurrent sexual relationships and may have limited agency to consistently use condoms, and 2) and may be injecting with their clients within their work environment. With over 50% of FSWs in Tijuana working without a work permit, both the limitations and benefits of the permit system might warrant further examination, considering that the routine medical examinations of permits are currently not occurring for the majority of FSWs. For men, intra-urban travel, deportation, negative experiences with the police, and perceived risk for acquiring HIV were predictive of injecting within the hot spot. However, receptive needle sharing was inversely associated, such that men who reported sharing were less likely to inject within the hot spot. As we described before, harm reduction and HIV prevention services are concentrated in this known ‘high-risk’ area. While this finding may evidence social desirable responses to this question, it may also indicate that men are changing behavior in light of recommendations to not share syringes as their ability to access clean injection equipment increases. Therefore, policies and funding to expand syringe exchange programs to further reduce HIV transmission among injectors in the HIV incidence hotspot should be considered. Also, outreach programs targeting the homeless and mobile populations should be expanded given that these populations may not be readily connected to more traditional service delivery mechanisms. Finally, because certain policing practices have been associated with especially risky substance use behaviors and were also associated with injection in the HIV hotspot, a dialogue with police in the area should be started to discuss the public health implications of enforcement activities.

More broadly, this work contributes to the growing body of literature that documents the dynamic role of ‘place’ in shaping health behaviors. Mexico enacted drug policy reform in the summer of 2010 that decriminalized possession of a small amount of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and marijuana for personal use drugs for personal use and mandated drug treatment (or jail time) for individuals caught by police possessing sub-threshold amounts of these drugs upon a 3rd strike (Moreno, Licea, & Ajenjo, 2010). Although the extent to which the new law will positively influence policing practices and lead to fewer of the negative police encounters we found associated with the HIV hotspot is not yet known, this policy may have an important bearing on both HIV risk and protective behaviors and is of great interest to Mexico, the U.S, and internationally.

Acknowledgments

Proyecto El Cuete and this analysis were made possible through funding by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (grants R01DA019829, R37DA019829, and K01DA020354). The funders had no role in the design of this study; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit this article for publication. Special thanks to the study participants who gave of their time; to Drs. Richard Shaffer and John Weeks, who served on the dissertation committee of N. Kori; and to Dr. Steffanie Strathdee who is the Principal Investigator of the Proyecto El Cuete cohort.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- Atlani L, Carael M, Brunet JB, Frasca T, Chaika N. Social change and HIV in the former USSR: the making of a new epidemic. Soc Sci Med. 2000;2000:1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Lozada R, Cornelius WA, Cruz MF, Magis-Rodriguez C, de Nuncio MLZ. Deportation Along the US-Mexico Border: Its Relation to Drug Use Patterns and Accessing Care. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11(1) doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Lozada R, Weeks JR, Magis-Rodriguez C, Firestone M, Strathdee SA. Intraurban Mobility and Its Potential Impact on the Spread of Blood-Borne Infections Among Drug Injectors in Tijuana, Mexico. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47(3):244–253. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.632465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Rusch ML, Weeks JR, Lozada R, Vera A, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Spatial Epidemiology of HIV Among Injection Drug Users in Tijuana, Mexico. [Article] Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2012;102(5):1190–1199. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.674896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucardo J, Brouwer KC, Magis-Rodriguez C, Ramos R, Fraga M, Perez SG, et al. Historical trends in the production and consumption of illicit drugs in Mexico: Implications for the prevention of blood borne infections. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucardo J, Semple SJ, Fraga-Vallejo M, Davila W, Patterson TL. A qualitative exploration of female sex work in Tijuana, Mexico. Archives Of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(4):343–351. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028887.96873.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Des Jarlais DC, Ross Z, Tempalski B, Bossak B, Friedman SR. Spatial Access to Syringe Exchange Programs and Pharmacies Selling Over-the-Counter Syringes as Predictors of Drug Injectors' Use of Sterile Syringes. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1118–1125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deren S, Kang SY, Colon HM, et al. Migration and HIV risk behaviors: Puerto Rican drug injectors in New York City and Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:812–816. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot J, Mijch AM, Street AC, Crofts N. HIV, ethnicity and travel: HIV infection in Vietnamese Australians associated with injection drug use. J Clin Virol. 2003;26:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Cooper HLF, Tempalski B, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom PL, et al. Relationships of deterrence and law enforcement to drug-related harms among drug injectors in US metropolitan areas. Aids. 2006;20(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196176.65551.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. [Article; Proceedings Paper] Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Iniguez-Stevens E, Brouwer KC, Hogg RS, Patterson TL, Lozada R, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Estimating the 2006 prevalence of HIV by gender and risk groups in Tijuana, Mexico. Gaceta Medica De Mexico. 2009;145(3):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas B, Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Neighborhood and HIV infection among IDU: Place of residence independently predicts HIV infection among a cohort of injection drug users. [Article] Health & Place. 2007;13(2):432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Firestone M, Ramos R, Burris S, Ramos ME, Case P, et al. Injecting drug users' experiences of policing practices in two Mexican-US border cities: Public health perspectives. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19(4):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JGB, Licea JAI, Ajenjo CR. Tackling HIV and drug addiction in Mexico. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):493–495. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60883-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Staines H, Lozada R, Orozovich P, Bucardo J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among female sex workers in 2 Mexico-US border cities. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197(5):728–732. doi: 10.1086/527379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Lozada RM, Ramos R, Cruz MF, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Syringe possession arrests are associated with receptive syringe sharing in two Mexico-US border cities. Addiction. 2008a;103(1):101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis B, Brouwer KC, Mills EJ, Hayes M, Kerr T, Hogg RS. Migration and transmission of blood-borne infections among injection drug users: Understanding the epidemiologic bridge. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(2–3) doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis B, Lloyd-Smith E, Small W, Tobin D, Stone D, Li K, et al. Harmful Microinjecting Practices Among a Cohort of Injection Drug Users in Vancouver Canada. [Article] Substance Use & Misuse. 2010;45(9):1351–1366. doi: 10.3109/10826081003767643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotin N, Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Nguyen L, Gallardo M, Vera A, et al. A Comparison of Registered and Unregistered Female Sex Workers in Tijuana, Mexico. [Article] Public Health Reports. 2010;125:101–109. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Fraga WD, Case P, Firestone M, Brouwer KC, Perez SG, et al. "Vivo-para-consumirla-y-la-consumo-para-vivir" -"I live to inject and inject to live" : High risk injection behaviors in Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005;82(3) doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Ojeda VD, Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Vera A, et al. Differential Effects of Migration and Deportation on HIV Infection among Male and Female Injection Drug Users in Tijuana, Mexico. Plos One. 2008;3(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodriguez C. Mexico's evolving HIV epidemic. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):571–573. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Philbin MM, Semple SJ, Pu M, Orozovich P, Martinez G, et al. Correlates of injection drug use among female sex workers in two Mexico-US border cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. [Accessed April 1, 2013];2013 http://wwwdhsgov/yearbook-immigration-statistics.