Abstract

Recently the switch-motor complex of bacterial flagella was found to be associated with a number of non-flagellar proteins, which, in spite of not being known as belonging to the chemotaxis system, affect the function of the flagella. The observation that one of these proteins, fumarate reductase, is essentially involved in electron transport under anaerobic conditions raised the question of whether other energy-linked enzymes are associated with the switch-motor complex as well. Here we identified two additional such enzymes in Escherichia coli. Employing fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) in vivo and pull-down assays in vitro we provided evidence for the interaction of FoF1 ATP synthase via its β subunit with the flagellar switch protein FliG and for the interaction of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase with FliG, FliM, and possibly FliN. Furthermore, we measured higher rates of ATP synthesis, ATP hydrolysis, and electron transport from NADH to oxygen in membrane areas adjacent to the flagellar motor than in other membrane areas. All these observations suggest the association of energy complexes with the flagellar switch-motor complex. Finding that deletion of the β subunit in vivo affected the direction of flagellar rotation and switching frequency further implied that the interaction of FoF1 ATP synthase with FliG is important for the function of the switch of bacterial flagella.

Keywords: FoF1 ATP synthase, flagellar motor, switch-motor complex, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, FliG

Introduction

Bacterial flagella rotate by a motor embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane, and the direction of rotation is dictated, according to signals received from the receptors, by a switch at the base of the motor.1 The flagellar motor is driven by ion-motive force, not by ATP. In the case of bacteria like Escherichia coli and Salmonella, it is driven by the protonmotive force (PMF).2 Thus, under physiological conditions, the PMF is generated by protons pumped out by NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and quinol oxidase bo3 during the transport of electrons from NADH to oxygen.3 In addition to driving the flagellar motor, the formed PMF is used to synthesize ATP by FoF1 ATP synthase and to drive PMF-dependent transport across the cytoplasmic membrane.3-5 When needed, ATP can be hydrolyzed by the FoF1 ATP synthase to generate PMF.6

The flagellar switch is a large complex composed of multiple copies of the proteins FliN, FliM and FliG.1,7 Recently it turned out that the switch-motor complex is much more complexed than originally thought, with a number of proteins found to be associated with the switch protein FliG (additional to the other switch proteins associated with it8). These include in E. coli the global gene expression regulator H-NS,9-12 the c-di-GMP receptor YcgR,13,14 and the electron-transport protein fumarate reductase (FRD).15 In Bacillus subtilis, the putative family II glycosyltransferase EpsE was found to be associated with FliG.16 All these proteins were demonstrated to affect the function of the switch-motor complex. Thus, specific point mutations in the hns gene were demonstrated to enhance the rotational speed of the flagellar motor, possibly by altering the conformation of FliG in a way that creates less friction within the surrounding stationary MotAB ring complex.10 EpsE was shown to act as a clutch, arresting flagellar rotation by disengaging the rotor from the power source.16 In addition to its interaction with FliG, YcgR also interacts with the switch protein FliM13 and with the stator protein MotA.11,17 The interaction with FliG13,14 and FliM14 was shown to be enhanced by c-di-GMP.13,14 The YcgR interaction with FliG was also shown to reduce the efficiency of torque generation and to induce counterclockwise motor bias,13,14 which is aided by the YcgR interaction with MotA.17 FRD was demonstrated to form a 1:1 dynamic complex with FliG, and this interaction was shown to be required for the normal function of FliG, expressed in flagellar assembly and switching.15 Even though the expression level of FRD under aerobic conditions is low,18 this protein was identified as the target of fumarate (a clockwise/switching factor required for switching the direction of rotation from counterclockwise to clockwise,19,20) transmitting the fumarate effect to the switch.15 The functional association of FRD with the switch raises the question of whether additional, other energy-linked enzymes are associated with the switch-motor complex. In this study we demonstrate that this is indeed the case, providing biochemical evidence for the association of FoF1 ATP synthase and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase with the switch-motor complex.

Results

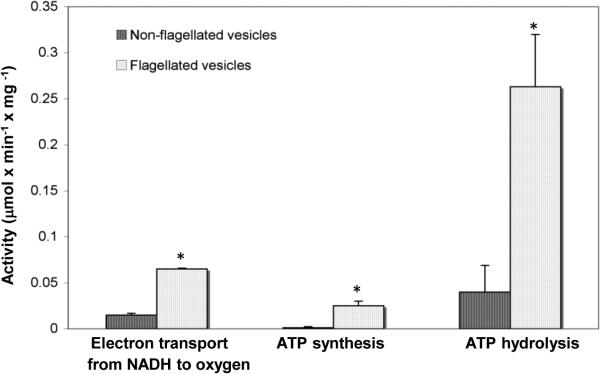

Higher energetic activities in membrane areas adjacent to the flagellar motor

To determine whether other enzymes, associated with the energy-metabolism system, interact with the switch-motor complex, we used two vesicular membrane preparations isolated from E. coli. One was a preparation enriched with membrane areas adjacent to the flagellar motor,21 termed hereafter flagellated vesicles (Fig. s1 in Supplementary data). The other was deficient in such vesicles and mainly included membrane vesicles from other areas (non-flagellated vesicles). (It should be noted that potential differences in membrane densities between both types of vesicles did not play a role in the isolation because the purification of the flagellated vesicles on a sucrose gradient was not according to their membrane density but rather according to flagellar density.)21 We measured ADP phosphorylation, ATP hydrolysis, and respiration from NADH to oxygen in both preparations. All three measured activities were significantly higher in the flagellated vesicles (Fig. 1). Indeed, these results may reflect higher activities of ATP synthase and the respiratory chain when located near the flagellar motor. However, a more logical explanation is that these enzymes are preferentially (but not exclusively) located in the motor's vicinity. We therefore investigated the possibility that these enzymes interact with the flagellar switch-motor complex. Unlike the respiratory activity from NADH to oxygen that involves many enzymes,3 the activities of ADP phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis are catalyzed by a single enzyme, FoF1 ATP synthase.6 Therefore, we started the investigation with this enzyme.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of activities between flagellated and non-flagellated vesicles. ATP hydrolysis was measured in the presence of NADH (0.2 mM) as an electron donor. Since more than 70% of the protein content of the flagellated vesicles is flagellin (determined from SDS gel of the two preparations; Fig. s1B), which is not an integral part of the membrane, we expressed the activity relative to the non-flagellin protein content of each fraction. The results are mean of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 according to Student's t-test.

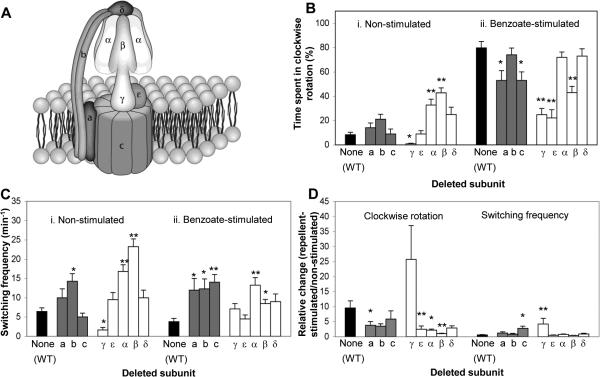

FoF1 ATP synthase mutants have aberrant flagellar rotation

The FoF1 ATP synthase is composed of eight different subunits6 (Fig. 2A). Following the presumption that if any one of the subunits interacts with the switch-motor complex, a mutant lacking this subunit may have an aberrant activity of the flagellar motor, we studied mutants from the Keio collection,22 deleted for the genes encoding the subunits of the FoF1 ATP synthase (one at a time). Some of these mutants had reduced fractions of swimming cells, but when these mutants were examined in a background of strain RP437, wild type for motility and chemotaxis, they all had wild-type-like motility, indicating that the FoF1 ATP synthase is not involved in flagellar assembly. (The reduced fractions of motile cells in the Keio collection background was apparently due to reduced number of flagella because cells of these mutants could be tethered to glass and rotate without first shearing their flagella.) Yet, when mutants from the Keio collection were tethered via their flagella to a glass slide and their rotation was monitored,23 it became apparent that some of the mutations caused defects in the direction of flagellar rotation (Fig. 2). We, therefore, first carried out a screen of the mutants from the Keio collection, looking for significant effects of the mutations on flagellar rotation. Next, according to the results of this screen, we continued working with a selected mutant in RP437 background.

Fig. 2.

Rotational behavior of tethered Δatp mutants from the Keio collection. (A) A scheme of FoF1 ATP synthase. (B) Time spent in clockwise rotation of cells before and after the addition of a repellent (50 mM benzoate). (C) Switching frequency of cells before and after the addition of benzoate. (D) Relative change in the clockwise rotation and switching frequency, calculated as the ratio between the responses of repellent-stimulated and non-stimulated cells. The results are the mean ± SEM of 28-70 cells. (The number of cells was determined on the basis of the criterion that additional cells did not change the mean.) The response of the Δβ mutant to benzoate suffered from large variability. Furthermore, Δε mutants were very scarce, i.e. hardly any cells were tethered (probably due to lack of flagella; no flagellar shearing was performed). One asterisk or two asterisks indicate results significantly different (P < 0.05 or P < 0.001, respectively) from those of wild type cells according to Kruskal-Wallis test, with a post-test by the Dunn method (in panels B, C) or two-way ANOVA with the data transformed to Log(X+1) (in panel D). Comparison of mutants for the ratio was performed by contrast t-tests on the means of the logged data.

Clearly, the mutants had a variety of phenotypes, depending on the deleted subunit (Fig. 2). These deletion-dependent phenotype differences appear to rule out the possibility that the phenotypes observed were the outcome of the loss of function of the enzyme. Had this been the case, all mutants should have had reduced clockwise rotation and switching frequency.24 Two mutants from the Keio collection were highly different from the wild-type control. The mutant lacking subunit γ rotated almost exclusively counterclockwise, with a resultant very low switching frequency. At the other extreme, the mutant lacking the β subunit (and, to a lesser extent, the mutant lacking the α subunit) had exceptionally high switching frequency and spent a higher fraction of time in the clockwise direction than the control (panels B-i and C-i in Fig. 2). Likewise, these mutants had exceptional responses to the repellent benzoate,25 (Fig. 2D) known to increase the fraction of time that E. coli flagella rotate clockwise.26 These results pointed to the β and γ subunits as potential candidates for interacting with the switch-motor complex. Given the large dimensions of the switch-motor complex and the relatively small area of the γ subunit available for interaction (Fig. 2A; see Discussion), the likelihood of an interaction between this subunit and the switch-motor complex appears very low. Therefore, following complementation experiments demonstrating that the β gene is indeed responsible for the observed phenotype (Fig. s2), we next focused on the β subunit in an RP437 background.

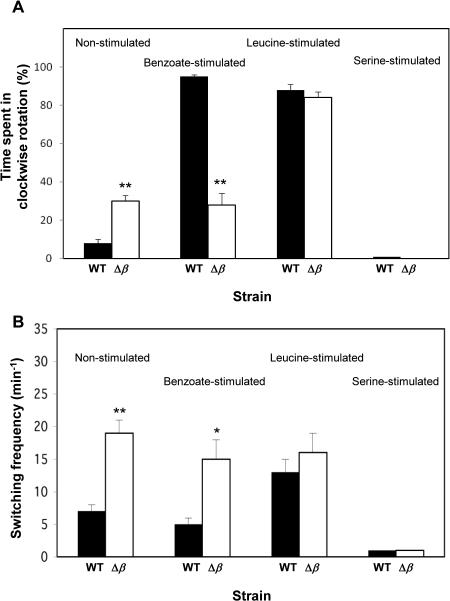

The β subunit of FoF1 ATP synthase is required for the switch function

To examine the effect of β subunit deletion on flagellar rotation in a background wild type for motility and chemotaxis, we transduced the βdeletion from the Keio collection to RP437 background. As before, non-stimulated RP437 cells lacking the β gene spent significantly higher fraction of time in clockwise rotation and had higher switching frequency compared to the wild-type cells (Fig. 3). Furthermore, as in the case of the Δβ mutant from the Keio collection (Fig. 2), the mutant in RP437 background did not respond to the repellent benzoate (Fig. 3). Yet, it did exhibit an apparently wild-type-like response to the repellent leucine and to the attractant serine — enhancement and repression of clockwise rotation, respectively (Fig. 3). Consistently, the response of the Δβ mutant to serine in ring-expansion assays on semi-solid agar (containing a minimal growth medium) was no worse than the Δδ control mutant; as a matter of fact, the ring expanded somewhat faster (Fig. s3). [The Δδ mutant was used as a control because, like the Δβ mutant, its FoF1 ATP synthase is not functional but, unlike the Δβ mutant, it exhibits a wild-type-like flagellar rotation (Fig. 2) and its core αβγ complex is intact27.] These observations suggest that deletion of the β subunit affects the rotational behavior, but the effects on the chemotactic response are stimulus-dependent. The reason for the difference between the repellents used in this study is not known, but it may be due to their different mechanisms of function, with benzoate working by both acidifying the cytoplasm28,29 and inhibiting fumarase30, and leucine working by another, unknown mechanism.

Fig. 3.

Rotational behavior of Δβ mutants in an RP437 background. The results are the mean ± SEM of 29-73 cells. (The number of cells was determined on the basis of the criterion that additional cells did not change the mean.) For each pair (wild-type versus mutant), one asterisk or two asterisks indicate results significantly different (P < 0.05 or P < 0.001, respectively) from those of wild type cells according to the Mann-Whitney test. (A) Time spent in clockwise rotation before and after chemotactic stimuli addition. (B) Switching frequency before and after chemotactic stimuli addition.

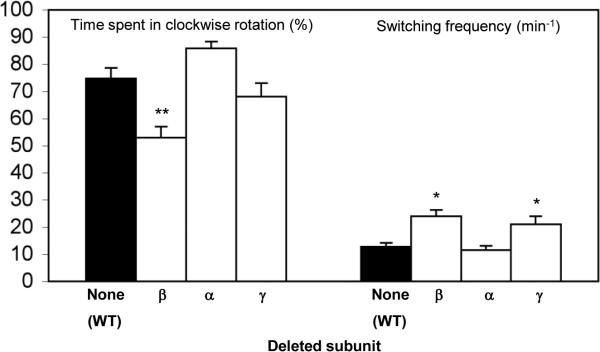

It was reported that the β subunit interacts with several components of the chemotaxis system — the receptor Tsr31 and the chemotaxis proteins CheZ and CheW31,32. Even though such high-throughput screens are prone to false-positive and false-negative results, we determined whether these potential interactions with chemotaxis proteins, if indeed they occur, contribute to the observed phenotypes of the Δβ mutant. To this end we investigated the rotational behavior of this mutant in a gutted background (strain RP1091, derived from RP43733) lacking all chemotaxis proteins and some of the receptors due to a deletion from cheA to cheZ.33 As a control, we also studied the rotational behavior of mutants in this background lacking two other subunits of the FoF1 ATP synthase, not reported to interact with the chemotaxis components: the α subunit because it is co-localized with the β subunit (Fig. 2A) and the γ subunit that, for the steric reasons mentioned above, is unlikely to interact with the switch-motor complex. The mutants in this background were transformed with a plasmid encoding the protein CheY, following induction with 0.1 mM IPTG, so as to enable flagellar rotation in both directions (the flagellar motor rotates exclusively counterclockwise in the absence of CheY34). In this background both CheZ and CheW are missing and an interaction of the β subunit with the receptor Tsr cannot affect the switch due to absence of the signaling system and the lack of direct interaction of the receptors with the switch-motor complex.21 The Δβ mutant in this background had reduced clockwise rotation and enhanced switching frequency relative to the β-containing strain, unlike the mutants lacking the α or γ subunit (Fig. 4; see Discussion). Even though most of these effects of the deletions were different from those in the Keio collection background (Fig. 2B, C; see Discussion for potential reasons), the observation of a phenotype resulting from the absence of the β subunit even in a cell that lacks most of the chemotaxis machinery endorses the suggestion that the complex formation of the β subunit with the switch is the important factor in the observed phenotypes, not its interaction with CheZ, CheW or Tsr.

Fig. 4.

Rotational behavior of non-stimulated CheY-containing gutted cells. Gutted cells (E. coli strain RP1091) containing pCA24N-cheY were grown to OD590 ≈ 0.25. At this stage IPTG (0.1 mM) was added and the cells continued growing for additional 2 h until harvested. To avoid energy depletion that may cause counterclockwise rotation, D,L-lactate (2 mM) was added to the motility buffer. The results are the mean ± SEM of 68-105 cells. (The number of cells was determined on the basis of the criterion that additional cells did not change the mean.) One asterisk or two asterisks indicate results significantly different (P < 0.05 or P < 0.001, respectively) from those of wild-type cells according to Kruskal-Wallis test, with a post-test by the Dunn method.

The β subunit forms a complex with the switch protein FliG

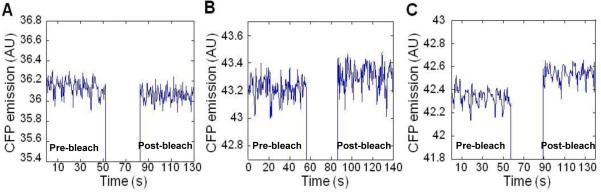

To determine whether the β subunit interacts with the switch-motor complex in vivo we first used acceptor photobleaching FRET. We employed wild-type E. coli cells (strain MG1655) expressing both subunit β fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and the switch protein FliG (or FliM or FliN) fused to cyan fluorescent protein (CFP). Fusion of the fluorescent proteins was done both at the N and C terminus domains of the proteins. No FRET signal was detected with both fusions of FliN and FliM (Fig. 5A as an example; Table 1 for a summary of all the results). In contrast, a weak FRET signal was observed for the β-YFP / FliG-CFP pair (Fig. 5B), and a stronger FRET signal for the YFP-β / FliG-CFP pair (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that, indeed, the β subunit interacts with the switch-motor complex and that its target protein is likely to be FliG. This interaction may depend on assembly of the switch-motor complex because it was only observed in the wild-type but not in the ΔflhC strain, in which the flagellar and chemotaxis proteins are not expressed33,35 (Table 1). Notably, although FRET demonstrates immediate proximity of two proteins and not necessarily their direct interactions, at the protein expression levels used here significant energy transfer is only expected to occur between proteins that form a specific complex. Such a complex can be detected by FRET even if, due to the rotation of FliG with the rest of the rotor, the complex is transient in nature. This is because the time of energy transfer (~2 ns) is six orders of magnitude shorter than the motor rotation.

Fig. 5.

In vivo FRET of the β subunit with the flagellar switch proteins. Fusion proteins were co-expressed pairwise in wild-type MG1655 cells. (A) Negative FRET signal for YFP-β / FliM-CFP pair. (B) Weak FRET signal for β-YFP / FliG-CFP pair, with a mean apparent FRET efficiency of 0.26±0.07% (2 experiments). (C) Significant FRET signal for YFP-β / FliG-CFP pair, with a mean apparent FRET efficiency of 0.53±0.02% (5 experiments). FRET is seen as an increase in CFP emission upon bleaching of YFP for 20 s using a 532 nm laser. The FRET efficiency was determined as the fractional change in CFP fluorescence after bleaching.

Table 1.

Summary of bleach FRET data for the β subunit and switch proteins

| FRET pairs | Strain | Mean of apparent FRET efficiency (%) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| YFP-β / FliG-CFP | MG1655 | 0.53 ± 0.02 |

| β-YFP / FliG-CFP | 0.26 ± 0.07 | |

| YFP-β / CFP-FliG | 0 | |

| β-YFP / CFP-FliG | 0 | |

| YFP-β / FliM-CFP | 0 | |

| β-YFP / FliM-CFP | 0 | |

| YFP-β / CFP-FliM | 0 | |

| β-YFP / CFP-FliM | 0 | |

| YFP-β / FliN-CFP | 0 | |

| β-YFP / FliN-CFP | 0 | |

| YFP-β / CFP-FliN | 0 | |

| β-YFP / CFP-FliN | 0 | |

| YFP-β / FliG-CFP | VS116 (ΔflhC) | 0 |

| β-YFP / FliG-CFP | 0 |

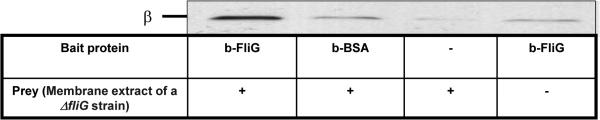

To verify this conclusion derived from in vivo experiments, we employed a pull-down assay between biotinylated FliG and a membrane extract of a ΔfliG strain, probing for the presence of the β subunit in the pulled samples. FliG clearly pulled down the β subunit (Fig. 6), suggesting complex formation between both proteins.

Fig. 6.

Pull-down of the β subunit from a membrane extract by biotinylated FliG. A membrane extract of a ΔfliG strain (0.4 mg/ml) was incubated overnight with biotinylated FliG (10 μM) or, as a negative control, biotinylated BSA (20 μM). Proteins were then precipitated with streptavidin–agarose beads and probed with an anti-β monoclonal antibody. The blot is representative of three independent experiments.

The NuoCD subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase interacts with the switch proteins

Since not only the activity of FoF1 ATP synthase was found higher near the flagellar motor but also the respiratory activity from NADH to oxygen (Fig. 1), it is reasonable that at least one of the respiratory chain enzymes would be associated with the flagellar motor. Indeed, an interaction between the first enzyme in this chain, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, and a switch protein of the flagellar motor has already been observed. Thus, the NuoCD subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase was demonstrated to interact with the switch protein FliM by yeast two-hybrid arrays31 and by co-purification assays using His-tagged proteins.32 In spite of this interaction, a ΔnuoCD mutant (in RP437 background) was found by us to behave similarly to the wild-type parent with respect to motility and direction of flagellar rotation (Fig. s4). We, therefore, wished to verify the interaction of NuoCD with the switch of the flagellar motor. We employed FRET in wild-type E. coli cells (strain MG1655) co-transformed with nuoCD fused to YFP, and FliG, FliM or FliN fused to CFP. No signal was detected with a fusion of FliM (Table 2). In contrast, a significant FRET signal was observed for the NuoCD-YFP / FliG-CFP pair, as well as for the NuoCD-YFP / FliN-CFP. In both cases, the FRET signal was observed in both orientations of the YFP and CFP (Table 2). In addition, when measuring the FRET signal in a strain lacking the native flagellar proteins (ΔflhC), only FliG showed complex formation with NuoCD (Table 2), suggesting either that the association of NuoCD with FliN is promoted by the switch-motor assembly or that this association is not direct but mediated by an interaction of NuoCD with FliG.

Table 2.

Summary of Bleach FRET data for NuoCD and switch proteins

| FRET pairs | Strain | Mean of apparent FRET efficiency (%) ± SD | Strain | Mean of apparent FRET efficiency (%) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YFP-NuoCD / FliG-CFP | MG1655 | 0.89 ± 0.02 | VS116 (ΔflhC) | 0 |

| NuoCD-YFP / FliG-CFP | 1.24 ± 0.06 | 0 | ||

| YFP-NuoCD / CFP-FliG | 0.8 ± 0.08 | 0 | ||

| NuoCD-YFP / CFP-FliG | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | ||

| YFP-NuoCD / FliM-CFP | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0 | ||

| NuoCD-YFP / FliM-CFP | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0 | ||

| YFP-NuoCD / CFP-FliM | 0 | 0 | ||

| NuoCD-YFP / CFP-FliM | 0 | 0 | ||

| YFP-NuoCD / FliN-CFP | 0.93 ± 0.10 | 0 | ||

| NuoCD-YFP / FliN-CFP | 1.2 ± 0.08 | 0 | ||

| YFP-NuoCD / CFP-FliN | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0 | ||

| NuoCD-YFP / CFP-FliN | 0.59 ± 0.10 | 0 |

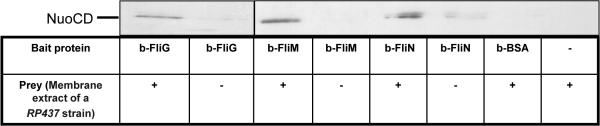

Since these results are different from earlier large screens of interacting proteins31,32 (see Discussion), we wished to validate the in vivo results (Table 2) by in vitro binding assays. We employed a pull-down assay, using biotinylated FliG, FliN or FliM as bait, and membrane extract of a RP437 strain as a prey, probing for the presence of NuoCD in the pulled samples. All three bait proteins pulled down NuoCD (Fig. 7). Taken together, the results suggest that NuoCD forms a complex with FliG, FliM, and possibly FliN (see Discussion).

Fig. 7.

Pull-down of the NuoCD subunit from a membrane extract by biotinylated switch proteins. A membrane extract of a RP437 strain (0.2 mg/ml) was incubated overnight with biotinylated FliG (5 μM), biotinylated FliM (5 μM), biotinylated FliN (5 μM), or, as a negative control, biotinylated BSA (5 μM). Proteins were then precipitated with streptavidin–agarose beads and probed with an anti-NuoCD antibody. The lanes with biotinylated FliG were taken from a separate experiment. The blot is representative of four independent experiments.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether energy-linked enzymes, additional to FRD,15 are associated with the flagellar switch-motor complex. The results presented demonstrate that, indeed, two additional enzymes — FoF1 ATP synthase and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase — interact with the switch-motor complex. For FoF1 ATP synthase, the major evidence involved in vivo demonstration that deletion of the β subunit of FoF1 ATP synthase radically affects flagellar behavior (Figs. 2, 3, 4, s2), and that this subunit forms a complex with FliG at the switch both in vivo (Fig. 5) and in vitro (Fig. 6). For NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, the evidence involved in vivo and in vitro demonstration of complex formation of the NuoCD subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase with the switch proteins (Fig. 7 and Table 2). Functional studies further suggested higher abundance of FoF1 ATP synthase and electron-transport respiratory enzymes near the switch-motor complex (Fig. 1). Below we discuss each of these findings and the possible link between them.

Interaction between FoF1 ATP synthase and the switch protein FliG

The results described above suggest the association of a fraction of the FoF1 ATP synthase molecules in the membrane with the switch protein FliG. The questions that come to mind are how such an interaction can occur from a steric point of view and what function this interaction fulfills.

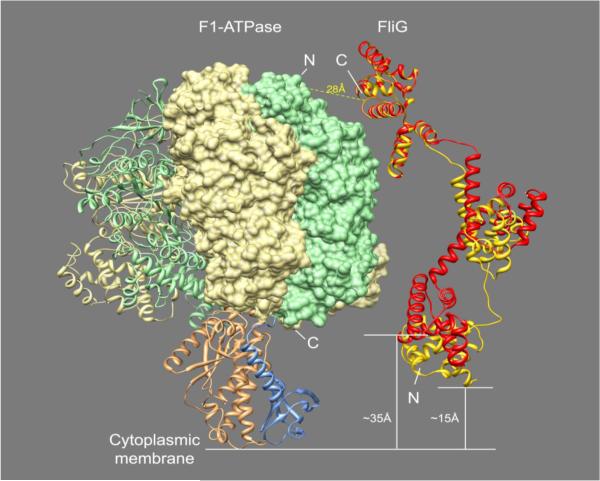

Steric considerations

The finding that the β subunit of FoF1 ATP synthase interacts with the switch protein FliG is intriguing because the interacting proteins each belong to very large complexes, raising the question of how such an interaction is sterically possible. The F1 sector of FoF1 ATP synthase is roughly a sphere on top of a stalk composed of the γ and ε subunits (Figs. 2A and 8). It seems reasonable that the association of FliG with the β subunit would occur on the top of the sphere (i.e., closer to the N-terminus of the β subunit, distal from the membrane surface), because the bottom part of the β subunit (i.e., the DELSEED-loop of each of the three β subunits at the C-terminus) makes contact with the γ subunit and is involved in mechanochemical coupling.36 This notion is apparently consistent with the FRET results, demonstrating a significantly stronger signal when YFP was at the N-terminus of the β subunit than when it was located at the other end of the protein (Table 1), which might indicate closer proximity of the N terminus to FliG in the complex.

Fig. 8.

A model depicting a potential mode of interaction between FliG and the β subunit. The model is based on the crystal structures of E. coli F1 ATPase (PDB accession code 3OAA)61 and FliG from Aquifex aeolicus (PDB accession code 3HJL)41, that were juxtaposed such that the average distance between the Cα of the N-terminal residue in the β subunit and the C-terminal residue in FliG is ~28 Å. This is an average distance taking into consideration the flexibility of the four C-terminal residues of FliG. Without any conformational changes in FliG, its N-terminal end is about 35 Å away from the cytoplasmic membrane, which might be too far for the known interaction between the N-terminal domain of FliG (FliGN) and FliF at the membrane.62 In the slightly modified structure of FliG (in yellow, compared to the original structure in red), obtained by minor torsional changes in the FliG loop at positions 192-197 (the loop that changes conformation between the three latest available structures of FliG)40,41,63 and the loop connecting the middle and N-terminal domains, the distance between FliGN and the membrane is narrowed to 15 Å only, and FliGN retains its original orientation, i.e. parallel to the membrane. Furthermore, since the model is based on a crystal structure that begins at the fifth amino acid residue,41 the distance between Lys 5 at the N-terminus of this modified model and the membrane can be spanned by these missing four amino acids. The figure was produced using Chimera software.64 Colors: light yellow, the α subunit of the F1 ATPase; light green, the β subunit; gold, the γ subunit; blue, the ε subunit; red, FliG; dark yellow, a modified structure of FliG.

As for FliG, it is reasonable that the interaction would be with a region important for switching, because lack of the β subunit resulted in altered switching (Figs. 2–4). From a steric point of view, the regions of FliG shown to be important for switching (the middle and C-terminal domains of FliG37-40) can all be candidates for interaction with the β subunit because they are on the surface of the protein and, therefore, accessible to interaction. In line with this notion, the FRET signal was only observed when CFP was at the C terminus of FliG (Table 1).

The model shown in Fig. 8 on the basis of the FRET results and the information mentioned above demonstrate that an interaction between FliG and the β subunit is feasible from a steric point of view. According to the model, the distance between the Cα of the N-terminus residue in the β subunit and the C-terminus residue in FliG is 28 Å, well within the FRET range of 100 Å.11 Since, according to all recently published models,33,35,36 the N- and C-terminus domains of FliG are parallel to the membrane, either one of the two interacting proteins should undergo a conformational change to reach the other protein. The model in Fig. 8 suggests that the C-terminal domain of FliG does it, shifting its position and becoming perpendicular to the membrane, while the N-terminus remains parallel to the membrane. It should be noted that even though there is no consensus between three recent models of FliG structure40-42 with respect to the position of specific FliG domains in the flagellar switch, in all of them the C-terminal domain is similarly located. Thus, our model is consistent with all these three models.

An intriguing question is why the complex formation between the β subunit and FliG was detected by FRET in vivo only when a complete motor was present (i.e., in wild-type background but not in ΔflhC background; Table 1), even though this interaction was also detected in vitro with purified FliG (Fig. 6). Three potential answers appear feasible, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive: (a) Even in vitro, a small fraction of the FliG molecules might be in complex with molecules of other switch proteins copurified with FliG. (b) The energy transfer between the fluorophores, but not the interaction between the proteins per se, may be dependent on FliG conformation within the intact motor. (c) Although the interaction can take place with free FliG, it may be further stabilized by FliG incorporation into the switch-motor complex.

In this study we did not investigate whether additional subunits of the FoF1 ATP synthase are involved in the interaction with FliG. The study demonstrated the interaction of the β subunit with FliG but it did not rule out other interactions. An important issue is the effect of each deletion on the assembly of the FoF1 ATP synthase. According to Klionsky and Simoni,27 null mutations in any of the individual Fo genes or a deletion of the entire Fo sector do not affect the assembly of the F1 sector; null mutations of the δ or ε subunit do not affect the assembly of the core αβγ complex; but such mutations in the α, β or γ subunit result in lack of assembly of the F1 sector. Indeed, only the mutants lacking the α, β and γ subunits had an aberrant non-stimulated flagellar rotation (Fig. 2B), but additional interactions without a phenotype are possible. This does not seem to be the only reason for the aberrant flagellar rotation: had the destructive effects on the assembly been the only effect, one would expect to see similar changes in the Δα, Δβ, and Δγ mutants, but this was not the case. Furthermore, the effects of the deletion of the α and γsubunits were dependent on the background (compare Fig. 4 with Fig. 2B-i, C-i), suggesting that they were not due to direct interaction of these subunits with the switch but rather to other reasons.

Functional considerations

The main function consistently affected by modulated levels of the β subunit is the switching frequency, which was enhanced by its absence (Figs. 2C-i, 3B, 4). Since the β subunit is part of FoF1 ATP synthase, this dependence on the presence of the β subunit suggests that the mere interaction of FoF1 ATP synthase via the β subunit with FliG is sufficient to maintain normal rotational behavior. This is consistent with the observations that deletion of subunit δ, or ε of F1, or each of the Fo subunits, did not affect flagellar rotation (Fig. 2) even though each of these deletions abolishes the FoF1 ATP synthase activity (verified by us by the lack of growth in a minimal medium with succinate as a carbon source — see Materials and Methods). All these observations imply that the activity of the FoF1 ATP synthase is not required for the observed change in flagellar rotation.

This conclusion may seem in conflict with the higher activity of FoF1 ATP synthase found close to the flagellum (Fig. 1). However, there is no conflict. A distinction should be made between two functions of FoF1 ATP synthase at the motor. One is to enable normal switching activity of the flagellar motor. For this function the activity of FoF1 ATP synthase is not important; all that apparently matters is the complex formation between the enzyme (via its β subunit) and FliG. The other function, suggested in this study (see below), is to locally provide (in energy-poor environments) energy for rotation by converting ATP to PMF — a function for which the enzyme should be active. So the complex between the β subunit and FliG appears to serve two functions: one enables normal activity of FliG, and the other localizes FoF1 ATP synthase (and its activity) close to the flagellar motor.

In view of published findings that the β subunit may interact with several components of the chemotaxis system (Tsr,31 CheZ and CheW31,32) a question that comes up is how certain we can be that the observed effects are, indeed, due to effects on the switch of the flagellar motor via FliG rather than effects on Tsr, CheZ or CheW. The finding that deletion of the β subunit from a strain devoid of CheZ, CheW and additional chemotaxis proteins is as effective as deletion from a strain possessing all these proteins (Fig. 2 versus 4) points to the FliG-β interaction as the main cause of the observed effects. This said, however, we cannot completely rule out a contribution of the chemotaxis system to the observed effects. For example, deletion of the β subunit affected the direction of flagellar rotation differently when the background was wild type for chemotaxis (Figs. 2B-i, 3A) and gutted (Fig. 4). Yet, with respect to the switching frequency — the change was similar in both cases. The different effects on the rotational direction could be either a reflection of the different starting states with respect to the direction of rotation (counterclockwise-biased in the wild-type background and clockwise-biased in the CheY-containing gutted background) or due to the involvement of the chemotaxis system in the case of the wild-type background.

Unlike the case of FRD, where the interaction with FliG was shown to be required for both flagellar assembly and switching the direction of rotation,15 in the case of FoF1 ATP synthase the interaction seems to be required for the latter only (Fig. 2). The observation that absence of the β subunit did not affect the intensity and extent of motility indicates that this subunit is not required for flagellar assembly. It is well established that another, very similar subunit is required for this function — the ATPase subunit FliI of the flagellar type III export apparatus.43,44 The apparent lack of involvement of the β subunit in flagellar assembly points to totally different roles of the β subunit and FliI. Furthermore, it has been shown that, unlike the β subunit (Figs. 5, 6), FliI cannot bind directly to any of the switch proteins; it can only do so via FliH, shown to bind to FliN.45

Interaction between NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and the switch

A number of lines of evidence suggest the interaction of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase with the switch-motor complex. In vivo FRET measurements demonstrated complex formation between NuoCD and the switch proteins FliN and FliG (Table 2), in vitro pull-down assays of biotinylated proteins showed the interaction of NuoCD with FliG, FliM and FliN (Fig. 7), NuoCD was found to co-purify with His-tagged FliM,32 and yeast two-hybrid screening implied NuoCD-FliM interaction.31 Beyond the questions (raised above also for the case of FoF1 ATP synthase) of how the interaction can occur from a steric point of view and what function this interaction fulfills, another intriguing question is why the various approaches, which indicated the interaction between NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and the switch-motor complex, each identified different switch proteins as the target of NuoCD. Our FRET results indicated that FliN cannot form a complex with NuoCD unless other flagellar proteins are present (Table 2, wild type versus ΔflhC backgrounds). Two potential reasons may account for this observation. One is that, to detect a FRET signal from the FliN-NuoCD interaction, FliN should be within an intact motor. According to this explanation, FliN should interact with other proteins in the switch-motor complex in order to acquire a conformation that enables energy transfer between the fluorophores linked to FliN and NuoCD. The other potential reason is that, due to the known interaction between FliG and FliN,8 the observed FliN-NuoCD interaction may essentially reflect the FliG-NuoCD interaction, shown to occur independently of other proteins (Table 2, strain ΔflhC). According to this explanation the FRET signal could be obtained because of the close proximity between FliN and NuoCD even though they do not interact directly.46,47 The FliN-NuoCD interaction observed in the pull-down assay may also be due to some unknown mediator. In contrast, it seems reasonable that FliM does interact with NuoCD. This is because three lines of evidence point to the occurrence of this interaction: the pull-down assays (Fig. 7), the results of the two-hybrid screening,31 and the co-purification of NuoCD with His-tagged FliM.32 Since the absence of a FRET signal does not necessarily mean that there is no interaction between two labeled proteins,46 it is conceivable that, in this case, the FRET experiments yielded false negative results, and that the NuoCD subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase forms a complex with FliG, FliM, and possibly FliN.

The respiratory activity from NADH to oxygen, found in this study to be higher near the flagellar motor (Fig. 1), includes the functions of several enzymes, from NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase to quinol oxidase bo3.3 Our findings that the NuoCD subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase interacts with the flagellar switch (Table 2 and Fig. 7) further suggest that this higher activity may be, at least in part, the outcome of association of respiratory chains with the switch-motor complex. Unlike the cases of FoF1 ATP synthase (Fig. 2) and FRD,15 absence of the NuoCD subunit did not affect the function of the switch-motor complex, suggesting that the only function of this interaction is to ensure the presence of the enzyme in the vicinity of the switch-motor complex. At this stage we do not know whether NuoCD is the only subunit that presumably hooks the respiratory chain to the switch-motor complex or whether additional subunits of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and additional respiratory enzymes are hooked as well. High-throughput screens found additional interactions between FliM and energy-linked components (such as binding of FliM to NuoI in Campylobacter jejuni31 and to the aerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in E. coli.31,32) However, the results of high-throughput screens should be taken with precaution because false-positive or false-negative results are always an option in such screens.

It should be emphasized that the demonstration of preferential association of FoF1 ATP synthase and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase with the switch-motor complex does not mean that these enzymes are almost exclusively localized near the flagellar motor. On the contrary, the measured activities of these enzymes in membrane areas remote from the switch-motor complex (Fig. 1) clearly indicates that the enzymes are spread all over the membrane, but they appear to be more concentrated near the switch-motor complex.

Physiological significance

The findings of interactions of energy-associated enzymes with the switch-motor complex — FoF1 ATP synthase (this study), NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (this study and 31,32) and FRD,15 as well as the measurements of higher respiratory and ATP synthesis/hydrolysis activities near the flagellar motor (this study) strongly suggest the association of energy complexes with the switch-motor complex. The mere existence of energy complexes has already been proposed. “Respirasomes” (i.e., supercomplexes of respiratory enzymes) were found in bacteria as well as in mammalian, yeast, and plant mitochondria.48-51 They were proposed to have a function in substrate channeling and structural stabilization of membrane protein complexes.50 FoF1 ATP synthase was found to interact with cytochrome caa3 of Bacillus pseudofirmus in vitro52 and to localize in vivo with succinate dehydrogenase within discrete domains on the membrane of Bacillus subtilis.53 NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase was found in a supercomplex with NADH dehydrogenase-2 in E. coli,51 and in a supercomplex with complexes III (ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase) and IV (cytochrome c oxidase) in Paracoccus denitrificans.50 Indeed, motor-associated complexes were not detected in cryo-electron tomography54 but this is not surprising: it is reasonable that these complexes are few in number and arranged in a random way; therefore, they may escape detection by the averaging method used in tomography.

An intriguing question is what the function of these energy complexes is at the switch-motor complex. The immediate thought that comes to mind is that there might be compartmentalization surrounding each motor, keeping the proteins required for its function in close proximity, and/or that the role of the complexes near the switch-motor complex is to locally provide energy for the function of the latter in energy-poor environments, where the PMF is significantly reduced. Further studies are required to understand the function of these complexes.

Not less intriguing is the question of the significance of the functionally-important interactions of so many proteins with FliG. It interacts with the β subunit of FoF1 ATP synthase (this study), FRD,15 H-NS,9-12 EpsE,16 and YcgR.13,14 All of them appear to be needed for, or to affect, the activity of FliG (each for a somewhat different activity). However, at least for the case of the FoF1 ATP synthase (this study) and FRD (G. Cecchini, unpublished), the enzymatic activity of the bound protein is not required for the activity of FliG. Why so many proteins interact with FliG and their mere presence (but not their activity) is needed for its function, and under what circumstances and timing each of these interactions occurs — all these are puzzling open questions.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Glucose, Tris, D,L-lactate, benzoate (sodium salt), polyethylene glycol dodecyl ether (Thesit), chloramphenicol, kanamycin, ampicillin, BSA, dithiothreitol, magnesium sulfate, magnesium chloride, triton X-100, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, vitamin B1, L-arabinose, MOPS, ADP and hexokinase were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA); sodium chloride was from Bio-lab Ltd. (Jerusalem, Israel); glycerol was from Frutarom (Haifa, Israel); EDTA and sucrose were from J. T. Baker (Deventer, Netherlands); isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was from Fermentas (Burlington, Canada); trichloroacetic acid, potassium hydrogen phosphate and potassium dihydrogen phosphate were from Merck (San Diego, CA, USA); L-methionine, L-leucine, L-histidine, L-threonine and L-serine were from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany); NADH was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany); K32Pi and [γ-32Pi]ATP were from Amersham Radiochemical Center (Amersham, England).

Bacterial strains

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. All the Δatp mutations (excluding BW25113ΔatpE which was generated by us) were from the Keio collection.22 The identity of each mutation was verified by PCR, and loss of activity of the FoF1 ATP synthase was verified by lack of growth on a minimal medium that contains succinate as the only carbon and energy source.55 Since strain BW25113, the wild-type parent of the Keio collection, was non-motile and we could not isolate motile colonies from it, we employed as the wild-type control its ΔmetE derivative. All cells used for swarm and tethering were grown in M9 medium supplemented with 0.5% casamino acids, 5 μg/ml vitamin B1, 20 mM glucose and the proper antibiotics. E. coli RP437 for the preparation of flagellated vesicles was grown in H1 minimal medium, supplemented with 15 mM glycerol and the required amino acids (L-methionine, L-leucine, L-histidine and L-threonine; 1 mM each). E. coli RP437 and RP437ΔfliG for the preparation of membrane extracts were grown in Luria broth. E. coli cells for FRET were grown in tryptone broth supplemented with ampicillin, chloramphenicol and/or kanamycin at final concentrations of 100, 35 and 50 μg/ml, respectively. Overnight cultures, grown at 30°C, were diluted 1:100 and grown at 34°C for about 4 h, to OD600 = 0.6, in the presence of the inducer IPTG or L-arabinose: The induction levels for pEWB1, pEWB2, pEWN1 and pEWN2 were 50, 100, 30 and 20 μM IPTG, and for pHL13, pHL15, pHL16, pHL50, pVS31 and pVS42 were 0.0001%, 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.01%, 0.01%, 0.001% arabinose, respectively. These induction levels yielded expression levels of ~10,000 protein copies per cell or less, quantified as described.11

Table 3.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Relevant phenotype/genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RP437 | Wild type for chemotaxis | 65 |

| EW388 | RP437ΔatpD | This study |

| EW405 | RP437ΔatpH | This study |

| EW389 | RP437ΔnuoCD | This study |

| DFB225 | RP437ΔfliG | 66 |

| BW25113 | Wild type | 67 |

| JW3805 | Wild type for chemotaxis; BW25113ΔmetE | 22 |

| JW3709 | BW25113ΔatpC (F1-ε) | 22 |

| JW3710 | BW25113ΔatpD (F1-β) | 22 |

| JW3711 | BW25113ΔatpG (F1-γ) | 22 |

| JW3712 | BW25113ΔatpA (F1-α) | 22 |

| JW3713 | BW25113ΔatpH (F1-δ) | 22 |

| JW3714 | BW25113ΔatpF (Fo-b) | 22 |

| JW3716 | BW25113ΔatpB (Fo-a) | 22 |

| EW390 | BW25113ΔatpE (Fo-c) | This study |

| EW379 | JW3710 + atpD | This study |

| EW380 | JW3710 + pCA24N | This study |

| RP1091 | RP437Δ(cheA cheW tar cheR cheB cheY cheZ) | 33 |

| EW267 | RP1091 + cheY | Fraiberg and Eisenbach, unpublished |

| EW385 | EW267ΔatpD | This study |

| EW386 | EW267ΔatpA | This study |

| EW387 | EW267ΔatpG | This study |

| MG1655 | Wild type for FRET measurements | 68 |

| VS116 | Δ flhC | 69 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCA24N | Expression vector; CmR | 70 |

| atpD | β subunit expression plasmid; pCA24N derivative | 70 |

| cheY | CheY expression plasmid; pCA24N derivative | 70 |

| pBAD33 | Expression vector; pACYC ori, pBAD promoter, CmR | 71 |

| pDK2 | Expression vector for cloning of N-terminal CFPA206K fusions; pTrc99a derivative | 69 |

| pDK4 | Expression vector for cloning of N-terminal YFPA206K fusions; pTrc99a derivative | 69 |

| pDK66 | Expression vector for cloning of C-terminal YFPA206K fusions; pTrc99a derivative | 69 |

| pDK85 | Expression vector for cloning of C-terminal CFPA206K fusions; pTrc99a derivative | 69 |

| pDK113 | Expression vector for cloning of C-terminal CFPA206K fusions; pTrc99a derivative; start code of CFPA206K was changed from atg to gtg | 11 |

| pDK79 | Expression vector; pACYC ori, pBAD promoter, KanR | 69 |

| pEWBI | YFP-β expression plasmid; pDK4 derivative | This study |

| pEWB2 | β-YFP expression plasmid; pDK66 derivative | This study |

| pEWN1 | YFP-NuoCD expression plasmid; pDK4 derivative | This study |

| pEWN2 | NuoCD-YFP expression plasmid; pDK66 derivative | This study |

| pHL13 | FliN-CFP expression plasmid; pDK79 derivative | 11 |

| pHL15 | FliG-CFP expression plasmid; pDK79 derivative | 11 |

| pHL16 | CFP-FliN expression plasmid; pDK79 derivative | 11 |

| pHL50 | CFP-FliG expression plasmid; pDK79 derivative | 11 |

| pVS31 | CFP-FliM expression plasmid; pBAD33 derivative | 11 |

| pVS42 | FliM-CFP expression plasmid; pBAD33 derivative | 11 |

Preparations

Flagellated and non-flagellated vesicles were prepared from E. coli RP437 essentially as described by Engström & Hazelbauer.21 The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with ice-cold KPi (50 mM, pH 7.0) plus EDTA (1 mM), brought to OD590 = 40, and disrupted by two brief periods (6 s) of sonication. The lysate was applied to a linear sucrose gradient and further treated as previously described.21 The vesicles (about 1 mg protein/ml) were kept in the storage buffer used for ADP phosphorylation [sucrose (250 mM), MOPS (10 mM, pH 7.5), MgCl2 (5 mM), glycerol (20% v/v) and dithiothreitol (1 mM)]56 and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Membrane extracts of strains RP437 and RP437ΔfliG were prepared from cells grown in Luria broth to OD590 = 1. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 50 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.4 supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were then lysed by sonication, and after removal of cell debris (7700 × g, 15 min, 4°C) the membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation (250,000 × g, 1 h, 4°C). Membranes were resuspended in the same buffer and Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.5% (30 min, on ice). Membranes were then centrifuged again (250,000 × g, 1 h, 4°C) and the supernatant was stored in liquid nitrogen.

For FRET measurements, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with tethering buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM L-methionine, 67 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium lactate, pH 7) and resuspended in 10 ml of tethering buffer.

Assays

ATP hydrolysis was measured at 30°C using [γ-32Pi]ATP as described by Perlin et al.57 The reaction was initiated by the addition of vesicles to the reaction mixture.

ADP phosphorylation was assayed in a thermostated chamber, open to air, at 30°C. The reaction buffer contained K32Pi (20 mM; 284 DPM/nmol; pH 7.4), sucrose (250 mM), Tris-HCl (5 mM, pH 7.4), MgSO4 (2 mM), EDTA (0.3 mM), glucose (32 mM), hexokinase (10 units/ml), ADP (1.5 mM) and BSA (free of fatty acids) (1 mg/ml). Vesicles (3 mg protein/ml) and NADH (0.2 mM) or D,L-lactate (2 mM) were added sequentially, and immediately thereafter aliquots were removed and mixed with an equal volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation and the organic phosphate was extracted and assayed as described.56

The electron transport activity of the membrane preparations from NADH to oxygen was measured spectroscopically at 30°C and 340 nm58 under the conditions described above for ADP phosphorylation but with KPi substituting for K32Pi. The reaction was initiated by the addition of vesicles (3 mg protein/ml) and NADH (0.2 mM).

Pull-down assays were performed essentially as described.15 Briefly, biotinylated switch proteins were mixed with membrane extracts of strains RP437 and RP437ΔfliG in solution A containing KPi (20 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (150 mM), MgSO4 (10 mM) and Thesit (0.05%), followed by overnight incubation with shaking at 4°C. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was incubated with streptavidin–agarose beads (Thermo scientific) for 1 h at 4°C, washed with solution A, boiled for 5 min with SDS sample buffer, applied to 12% SDS–PAGE, and the gels transferred to membranes that were probed with either mouse anti-β monoclonal antibody (MitoSciences) for detection of the β subunit, or rabbit anti-NuoCD antibody (a generous gift from Prof. Takao Yagi, Department of Molecular and Experimental Medicine, The Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA) for detection of the NuoCD subunit.

Cells for ring-formation assays on semi-solid agar were grown until mid-exponential phase and their OD590 was then adjusted to 0.5. 5 μl-portions of each cell suspension were inoculated in plates containing 0.3% agar and H1 medium supplemented with 0.4% glycerol, 0.1 mM L-serine, and 0.1 mM of each of the amino acids necessary for growth (L-methionine, L-leucine, L-histidine and L-threonine). For the mutant strains, the suspension also contained kanamycin (50 μg/ml). The plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h before photographing them.

Determination of the direction of flagellar rotation was performed by the tethering assay23 essentially as described.59 Briefly, cells grown to mid-exponential phase were either subjected to blending for shearing their flagella (strains BW25113ΔmetE, JW3711, EW267, EW385-8, EW390 and RP437) or not (all other strains). Following harvesting by centrifugation (46 × g, 5 min), cells were washed twice in motility buffer (10 mM KPi, pH 7.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM L-methionine) and tethered through their flagella to glass slides in a flow chamber.60 The rotation of the tethered cells was recorded on videotape and the direction of each spinning cell was analyzed in 1 min segments using Matlab-based homemade software. In all the experiments the average rotational rate was rather constant during the measurement and similar in all the studied strains.

Acceptor photobleaching FRET measurements were performed as described.11 Briefly, cells were concentrated about 10-fold by centrifugation, resuspended in tethering buffer and applied to a thin agarose pad (1% agarose in tethering buffer). Bleaching of YFP was accomplished by a 20 s illumination with a 532 nm diode laser (Rapp OptoElectronic). CFP emission was recorded before and after bleaching of YFP using photon counters (Hamamatsu) mounted on a custom-modified Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope, and FRET was calculated as the CFP signal increase divided by the total signal after bleaching. Notably, thus determined apparent FRET efficiencies are substantially lower than the theoretical FRET efficiencies expected for the same pairs based on the distance between CFP and YFP in the complex. This is due to the contribution of the background fluorescence to the CFP channel, which diminishes the calculated FRET signal by a factor of CCFP/(CCFP + CB), where CCFP is the specific CFP fluorescence and CB is fluorescence background.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by Instat software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and SAS 9.1 software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Hillary Voet for her assistance in statistical analysis; Dr. Takao Yagi for the anti-NuoCD antibody; Dr. Miriam Eisenstein for her help with the crystallographic models; Michael Levant for writing the computer software for analysis of the rotational behavior of tethered cells, and Dr. Wayne Frasch for critical reading of the manuscript. M.E. is an incumbent of the Jack and Simon Djanogly Professorial Chair in Biochemistry. This study was supported by US–Israel Binational Science Foundation research grant no. 2009161, NIH grant GM61606, and DFG Cluster of Excellence CellNetworks.

Abbreviations

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- FRD

fumarate reductase

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- PMF

protonmotive force

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Rose M. Johnstone, an excellent scientist and a wonderful human being, who was involved in this study at its onset and passed away shortly thereafter.

References

- 1.Berg HC. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen SH, Adler J, Gargus JJ, Hogg RW. Chemomechanical coupling without ATP: The source of energy for motility and chemotaxis in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1974;71:1239–1243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unden G, Bongaerts J. Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1320:217–234. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jormakka M, Byrne B, Iwata S. Protonmotive force generation by a redox loop mechanism. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cecchini G. Function and structure of complex II of the respiratory chain. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:77–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T. ATP synthase--a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenbach M. Chemotaxis. Imperial College Press; London: 2004. Chapter 3 (Bacterial chemotaxis). pp. 53–215. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang H, Braun TF, Blair DF. Motility protein complexes in the bacterial flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;261:209–221. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marykwas DL, Schmidt SA, Berg HC. Interacting components of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli revealed by the two-hybrid system in yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;256:564–576. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donato GM, Kawula TH. Enhanced binding of altered H-NS protein to flagellar rotor protein FliG causes increased flagellar rotational speed and hypermotility in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24030–24036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Sourjik V. Assembly and stability of flagellar motor in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;80:886–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul K, Carlquist WC, Blair DF. Adjusting the Spokes of the Flagellar Motor with the DNA-Binding Protein H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5914–5922. doi: 10.1128/JB.05458-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang X, Gomelsky M. A post-translational, c-di-GMP-dependent mechanism regulating flagellar motility. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;76:1295–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “backstop brake” mechanism. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen-Ben-Lulu GN, Francis NR, Shimoni E, Noy D, Davidov Y, Prasad K, Sagi Y, Cecchini G, Johnstone RM, Eisenbach M. The bacterial flagellar switch complex is getting more complex. EMBO J. 2008;27:1134–1144. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair KM, Turner L, Winkelman JT, Berg HC, Kearns DB. A molecular clutch disables flagella in the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Science. 2008;320:1636–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1157877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, Kaever V, Sourjik V, Roth V, Jenal U. Second messenger-mediated adjustment of bacterial swimming velocity. Cell. 2010;141:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones HM, Gunsalus RP. Transcription of the Escherichia coli fumarate reductase genes (frdABCD) and their coordinate regulation by oxygen, nitrate, and fumarate. J. Bacteriol. 1985;164:1100–1109. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.3.1100-1109.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barak R, Eisenbach M. Fumarate or a fumarate metabolite restores switching ability to rotating flagella of bacterial envelopes. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:643–645. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.643-645.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montrone M, Eisenbach M, Oesterhelt D, Marwan W. Regulation of switching frequency and bias of the bacterial flagellar motor by CheY and fumarate. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3375–3380. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3375-3380.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engström P, Hazelbauer GL. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins are distributed in the membrane independently from basal ends of bacterial flagella. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;686:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. 2006 0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman M, Simon M. Flagellar rotation and the mechanism of bacterial motility. Nature. 1974;249:73–74. doi: 10.1038/249073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shioi J-I, Galloway RJ, Niwano M, Chinnock RE, Taylor BL. Requirement of ATP in bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:7969–7975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tso W-W, Adler J. Negative chemotaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1974;118:560–576. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.2.560-576.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen SH, Reader RW, Kort EN, Tso W-W, Adler J. Change in direction of flagellar rotation is the basis of the chemotactic response in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1974;249:74–77. doi: 10.1038/249074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klionsky DJ, Simoni RD. Assembly of a functional F1 of the proton-translocating ATPase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:11200–11206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Repaske DR, Adler J. Change in intracellular pH of Escherichia coli mediates the chemotactic response to certain attractants and repellents. J. Bacteriol. 1981;145:1196–1208. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1196-1208.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kihara M, Macnab RM. Cytoplasmic pH mediates pH taxis and weak-acid repellent taxis of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1981;145:1209–1221. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1209-1221.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montrone M, Oesterhelt D, Marwan W. Phosphorylation-independent bacterial chemoresponses correlate with changes in the cytoplasmic level of fumarate. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:6882–6887. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6882-6887.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopala SV, Titz B, Goll J, Parrish JR, Wohlbold K, McKevitt MT, Palzkill T, Mori H, Finley RL, Jr., Uetz P. The protein network of bacterial motility. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:128. doi: 10.1038/msb4100166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arifuzzaman M, Maeda M, Itoh A, Nishikata K, Takita C, Saito R, Ara T, Nakahigashi K, Huang HC, Hirai A, Tsuzuki K, Nakamura S, Altaf-Ul-Amin M, Oshima T, Baba T, Yamamoto N, Kawamura T, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Kitagawa M, Tomita M, Kanaya S, Wada C, Mori H. Large-scale identification of protein-protein interaction of Escherichia coli K-12. Genome Res. 2006;16:686–691. doi: 10.1101/gr.4527806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkinson JS, Houts SE. Isolation and behavior of Escherichia coli deletion mutants lacking chemotaxis functions. J. Bacteriol. 1982;151:106–113. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.106-113.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clegg DO, Koshland DE. The role of a signaling protein in bacterial sensing: Behavioral effects of increased gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:5056–5060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kentner D, Sourjik V. Spatial organization of the bacterial chemotaxis system. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:619–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mnatsakanyan N, Krishnakumar AM, Suzuki T, Weber J. The role of the betaDELSEED-loop of ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11336–11345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900374200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Way SM, Millas SG, Lee AH, Manson MD. Rusty, jammed, and well-oiled hinges: Mutations affecting the interdomain region of FliG, a rotor element of the Escherichia coli flagellar motor. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3173–3181. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3173-3181.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown PN, Terrazas M, Paul K, Blair DF. Mutational analysis of the flagellar protein FliG: sites of interaction with FliM and implications for organization of the switch complex. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:305–312. doi: 10.1128/JB.01281-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Togashi F, Yamaguchi S, Kihara M, Aizawa S-I, Macnab RM. An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:2994–3003. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2994-3003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minamino T, Imada K, Kinoshita M, Nakamura S, Morimoto YV, Namba K. Structural insight into the rotational switching mechanism of the bacterial flagellar motor. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee LK, Ginsburg MA, Crovace C, Donohoe M, Stock D. Structure of the torque ring of the flagellar motor and the molecular basis for rotational switching. Nature. 2010;466:996–1000. doi: 10.1038/nature09300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul K, Gonzalez-Bonet G, Bilwes AM, Crane BR, Blair D. Architecture of the flagellar rotor. EMBO J. 2011;30:2962–2971. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imada K, Minamino T, Tahara A, Namba K. Structural similarity between the flagellar type III ATPase FliI and F1-ATPase subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:485–490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogler AP, Homma M, Irikura VM, Macnab RM. Salmonella typhimurium mutants defective in flagellar filament regrowth and sequence similarity of FliI to FoF1, vacuolar, and archaebacterial ATPase subunits. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3564–3572. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3564-3572.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMurry JL, Murphy JW, Gonzalez-Pedrajo B. The FliN-FliH interaction mediates localization of flagellar export ATPase FliI to the C ring complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11790–11798. doi: 10.1021/bi0605890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenworthy AK. Imaging protein-protein interactions using fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. Methods. 2001;24:289–296. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kentner D, Sourjik V. Dynamic map of protein interactions in the Escherichia coli chemotaxis pathway. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:238. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schagger H, Pfeiffer K. Supercomplexes in the respiratory chains of yeast and mammalian mitochondria. EMBO J. 2000;19:1777–1783. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eubel H, Jansch L, Braun HP. New insights into the respiratory chain of plant mitochondria. Supercomplexes and a unique composition of complex II. Plant physiol. 2003;133:274–286. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stroh A, Anderka O, Pfeiffer K, Yagi T, Finel M, Ludwig B, Schagger H. Assembly of respiratory complexes I, III, and IV into NADH oxidase supercomplex stabilizes complex I in Paracoccus denitrificans. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5000–5007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sousa PM, Silva ST, Hood BL, Charro N, Carita JN, Vaz F, Penque D, Conrads TP, Melo AM. Supramolecular organizations in the aerobic respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Biochimie. 2011;93:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu X, Gong X, Hicks DB, Krulwich TA, Yu L, Yu CA. Interaction between cytochrome caa3 and F1F0-ATP synthase of alkaliphilic Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4 is demonstrated by saturation transfer electron paramagnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry assays. Biochemistry. 2007;46:306–313. doi: 10.1021/bi0619167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson AS, van Horck S, Lewis PJ. Dynamic localization of membrane proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2004;150:2815–2824. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen S, Beeby M, Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Hendrixson DR, Briegel A, Li Z, Shi J, Tocheva EI, Muller A, Dobro MJ, Jensen GJ. Structural diversity of bacterial flagellar motors. EMBO J. 2011 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butlin JD, Cox GB, Gibson F. Oxidative phosphorylation in Escherichia coli K12. Mutations affecting magnesium ion- or calcium ion-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase. Biochem. J. 1971;124:75–81. doi: 10.1042/bj1240075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hempfling WP, Herzberg ET. Techniques for measurement of oxidative phosphorylation in intact bacteria and membrane preparations of Escherichia coli. Meth. Enzymol. 1979;55:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perlin DS, Latchney LR, Senior AE. Inhibition of Escherichia coli H+ATPase by venturicidin, oligomycin, and ossamycin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;807:238–244. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(85)90254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gutman M, Hartstein E. Distinction between NAD- and NADH-binding forms of mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase as shown by inhibition with thenoyltrifluoroacetone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;481:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ravid S, Eisenbach M. Correlation between bacteriophage chi adsorption and mode of flagellar rotation of Escherichia coli chemotaxis mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1983;154:604–611. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.604-611.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berg HC, Block SM. A miniature flow cell designed for rapid exchange of media under high-power microscope objectives. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1984;130:2915–2920. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cingolani G, Duncan TM. Structure of the ATP synthase catalytic complex (F(1)) from Escherichia coli in an autoinhibited conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kihara M, Miller GU, Macnab RM. Deletion analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliG of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:3022–3028. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3022-3028.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown PN, Hill CP, Blair DF. Crystal structure of the middle and C-terminal domains of the flagellar rotor protein FliG. EMBO J. 2002;21:3225–3234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parkinson JS. Complementation analysis and deletion mapping of Escherichia coli mutants defective in chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 1978;135:45–53. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.1.45-53.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lloyd SA, Tang H, Wang X, Billings S, Blair DF. Torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli: evidence of a direct role for FliG but not for FliM or FliN. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:223–231. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.223-231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blattner FR, Plunkett G, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kentner D, Thiem S, Hildenbeutel M, Sourjik V. Determinants of chemoreceptor cluster formation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:407–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guzman L-M, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.