Part II: Today’s contentious negotiations echo those from the battle over medicare a half-century ago

Doctors refuse to compromise, says one side. The government cares more about its budget than patients, says the other side. Doctors have rejected a “very fair offer,” says a provincial health minister. Patients can’t wait for the government to balance its books, says a medical association. You know, this all sounds mighty familiar.

Much of the rhetoric thrown around today in scuffles between governments and physicians might ring a bell for students of medical history. More than 50 years ago, doctors were also accused of being too stubborn to accept changes to pay structure, and a provincial government was also charged with putting fiscal concerns before patient needs. Of course, if that old saying holds any merit — “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” — perhaps a refresher is in order. There seems, after all, to be a little bit of history repeating itself.

The origin of conflict between provincial governments and physicians can be summed up in one word: medicare. It therefore dates back to midnight of July 1, 1962, when the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Act passed into law, introducing the first universal, government-run, single-payer health system to North America. All of one minute later, most of Saskatchewan’s doctors went on strike.

Actually, to be precise, the fighting between the government and doctors in Saskatchewan began a couple of years earlier, during the 1960 provincial election. Premier Tommy Douglas had made universal health care the main peg of his re-election campaign. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan fiercely opposed the idea, contending that government interference in medicine would do far more harm than good.

A public battle ensued, pitting doctors against politicians. Debates were held, pamphlets were circulated, pledges were signed. Did the whole affair stay civil and free of propaganda? Well, you could say that. But only if you enjoy being wrong.

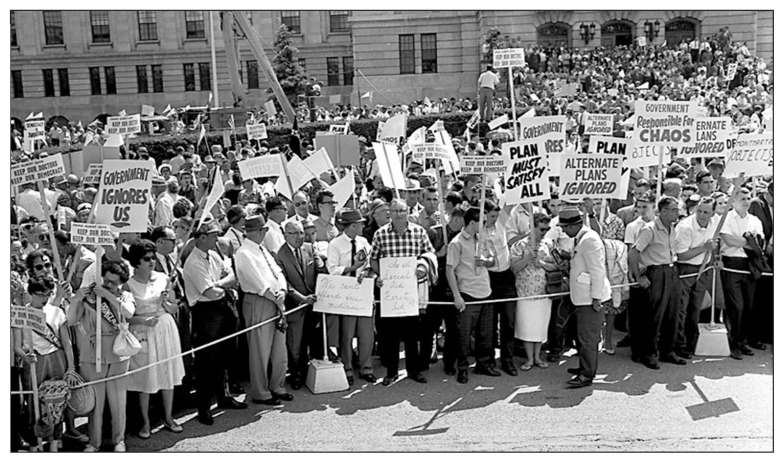

Public protest in Saskatchewan in early 1960s over government’s plans to introduce medicare.

Image courtesy of Morris Predinchuk/Morris Studios fonds/Saskatchewan Archives Board

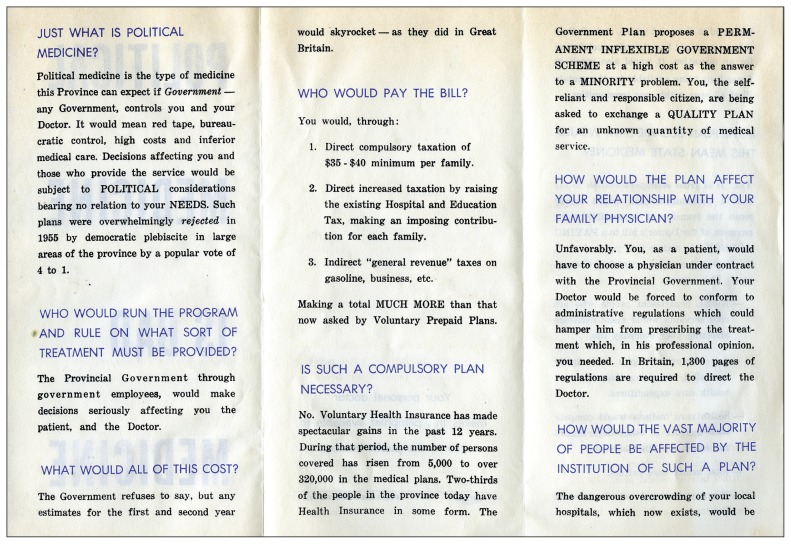

Let’s start with some of the literature circulated by opponents of medicare. One pamphlet, Political Medicine is Bad Medicine, was chockablock with scary warnings and seasoned with a liberal sprinkling of words in all-caps for emphasis. Red Tape! Skyrocketing costs! Inferior care! The premier’s plan “proposes a PERMANENT INFLEXIBLE GOVERNMENT SCHEME at a high cost” that would subject medicine “to POLITICAL considerations bearing no relation to your NEEDS.”

Then there was the infamous flyer — later used by Premier Douglas to shame his opponents, according to Saturday Night magazine — that suggested many doctors would flee the province if the medicare bill passed. “They’ll have to fill up the profession with the garbage of Europe,” read one excerpt, a quote from an anonymous doctor taken from the Toronto Telegram. “Some of the European doctors who come out here are so bad we wonder if they ever practised medicine.”

Later, some in the anti-medicare camp acknowledged that mistakes were made, passion had trumped reason, and the medical profession had suffered for engaging in political mudslinging. “Many doctors concede privately that they went too far, that the campaign lost them prestige in their communities,” reported Saturday Night magazine.

Of course, the premier was no stranger to rhetoric himself. In fact, according to some political commenters of the time, he was a master of the form. He accused the province’s physicians of using “abominable” and “despicable” tactics and pedalling “scurrilous trash.”

In the end, Douglas and his party, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, won the election and pushed ahead with their health system plan. The doctors and government set aside their differences and all lived happily ever after. Yeah, right.

Medicare was coming to Saskatchewan — that battle was over — but physicians still weren’t cooperating with the government. They focused their efforts on changing sections of the proposed medicare act, specifically those that granted the government almost unlimited power to control the practice of medicine.

“There was no provision for negotiation. The doctors would simply have to do what the government told them to do, and be paid what the government said they would be paid,” Dr. Marc Baltzan (1929–2005), a Saskatoon nephrologist and former president of the Canadian Medical Association, wrote in a 1984 article in Canadian Family Physician entitled, “Doctor/Government Fee Negotiations in Canada.”

After the act became law, unchanged, the province’s physicians closed their offices, though they still provided emergency services in hospitals. The standoff lasted 23 days, ending only after both sides compromised and signed the Saskatoon Agreement. The deal amended the act to ensure doctors would maintain their independence and could, if they wanted, opt out of medicare and bill patients directly.

The deal was brokered by Lord Stephen Taylor, a British doctor and politician who helped implement the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Later, reflecting on his Saskatchewan adventure, Taylor wrote that much of the animosity between the two parties arose because they did not understand each other at all. The government did not anticipate how much their plan would threaten the autonomy of a proud profession. Physicians “could not believe that the government was composed of honest and responsible people.”

Taylor, a man of both medicine and government, chose to take a dispassionate view of the conflict. “I see honest men on both sides, well motivated but mystified by the actions of their opponents.”

Decades later, debate over another act — the Canada Health Act, federal legislation adopted in 1984 — again showed just how differently government and physicians can view a change to how doctors are paid. This time, the government was putting an end to extra billing by physicians. But according to Baltzan, as mentioned in his Canada Family Physician article cited above, this was merely a “political euphemism” for banning a patient’s right to be reimbursed by the government when billed directly by a doctor.

In his lament over the passing of the “deceitful bill,” Baltzan suggested that it was important to revisit the original fight over medicare in Saskatchewan because “it shows that there is nothing new under the sun: it contains all the elements of physician–government confrontation that have been replayed again and again during the Canada Health Act debate.”

Now, more than 30 years later, it might not be a stretch to say there is still nothing new under the sun regarding negotiations between doctors and government. When things go bad, as they have in Ontario, both sides sometimes resort to a little time-tested rhetoric. Then again, though some of the messages sound familiar, other elements of physician–government showdowns have changed since 1962. For one, doctors back then didn’t have Twitter accounts.

Coming up: Part III: Taking the fight online

The pamphlet Political Medicine is Bad Medicine.

Image courtesy of University of Saskatchewan, University Library, University Archives & Special Collections, W.P. Thompson fonds, MG17S1/H/136