Abstract

Purpose of review

The aim of the present review was to discuss the effects of pollen components on innate immune responses.

Recent findings

Pollens contain numerous factors that can stimulate an innate immune response. These include intrinsic factors in pollens such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases, proteases, aqueous pollen proteins, lipids, and antigens. Each component stimulates innate immune response in a different manner. Pollen nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases induce reactive oxygen species generation and recruit neutrophils that stimulate subsequent allergic inflammation. Pollen proteases damage epithelial barrier function and increase antigen uptake. Aqueous pollen extract proteins and pollen lipids modulate dendritic cell function and induce Th2 polarization. Clinical studies have shown that modulation of innate immune response to pollens with toll-like receptor 9- and toll-like receptor 4-stimulating conjugates is well tolerated and induces clear immunological effects, but is not very effective in suppressing primary clinical endpoints of allergic inflammation.

Summary

Additional research on innate immune pathways induced by pollen components is required to develop novel strategies that will mitigate the development of allergic inflammation.

Keywords: allergic inflammation, aqueous pollen extract, lipid, NADPH oxidase, reactive oxygen species

INTRODUCTION

Environmental pollens are well known as major causes of allergic disorders such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis all over the world. There is a large body of literature describing the adaptive immune responses induced by pollens. Only recently, however, innate responses to pollens and their components have been described. Innate immune responses usually act against potential pathogens or endogenous molecules released by damaged cells that have conserved molecular patterns, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns. Increasing evidence shows that various pollen components stimulate innate immune responses that induce allergic airway inflammation. In the present review, we summarize recent data describing the pollen-induced innate immune responses that contribute to allergic inflammation.

INTRINSIC POLLEN NADPH OXIDASES AND TWO-SIGNAL HYPOTHESIS OF POLLEN-INDUCED ALLERGIC INFLAMMATION

The contribution of oxidative stress to the pathogenesis of asthma and allergic diseases is an important area of research. Environmental factors such as ultrafine particles, diesel exhaust particles, smoking, and pollens can induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH) [1]. Pollen allergen provocation induces ROS generation in human patients with bronchial asthma and seasonal allergic rhinitis [2–4]. ROS promotes allergic inflammation by changing dendritic cell function and modulating the Th1/Th2 balance [5–8].

Allergenic pollens have intrinsic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases [9]. In a landmark study, pollen NADPH oxidases from ragweed pollen extract (RWPE) were separated into NADPH oxidase-positive (RWPENOX+) and oxidase-negative fractions (RWPENOX−) by column chromatography. Intranasal challenge with RWPENOX+, but not RWPENOX−, induced significant neutrophil recruitment in naïve mice and mice lacking T cells, B cells, or mast cells [9]. RWPENOX+ increased oxidized glutathione (GSSG) or 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which rapidly causes tyrosine phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and subsequent secretion of interleukin-8 [9]. In the experimental allergy model, RWPENOX+-induced oxidative stress significantly augmented the metaplasia of mucin-producing cells and the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the broncho-alveolar lavage and peribronchial areas [9]. Heat-inactivated RWPE, which lack NADPH oxidase activity, fail to induce allergic airway inflammation. Simultaneously administering an ROS generator such as xanthine and xanthine oxidase with heat-inactivated RWPE reconstitutes induction of allergic airway inflammation [9,10]. Similarly to the airway mucosa, exposure of RWPENOX+ generates superoxide anion in the eye conjunctiva, and this oxidative insult promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells into the conjunctiva [10].

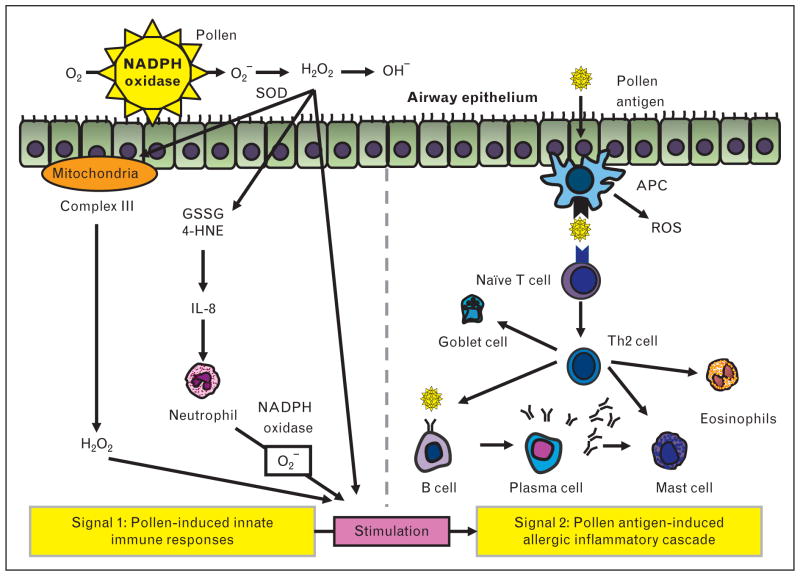

On the basis of these and other studies, a two-signal hypothesis has been proposed for induction of pollen-induced allergic inflammation (Fig. 1): ‘signal 1’, consisting of innate signaling pathways activated by pollen-induced ROS, boosts ‘signal 2’, the classical pathway of antigen presentation to T cells that impart immunological specificity to the immune response. Support for the ‘two-signal hypothesis’ comes from several studies in addition to the landmark study discussed above [9]. One study [11] demonstrated that removal of signal 1 by prior administration of antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, N-acetyl-cysteine, or tocopherol coadministered with RWPE profoundly inhibits RWPE-induced allergic airway inflammation. Likewise, administration of the antioxidant lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein, inhibits RWPE-induced intracellular ROS generation in epithelial cells and allergic airway inflammation in a mouse experimental model of asthma [12,13]. Finally, signal 1 is not just a laboratory phenomenon observed in cultured cells and mice because human studies have revealed that challenge with pollen extracts in patients with asthma induces early superoxide generation at the site of challenge [14,15] and recruits neutrophils to the airways [16].

FIGURE 1.

Two-signal hypothesis of pollen-induced allergic inflammation. ROS generated by the pollen NADPH oxidases causes GSSG or 4-HNE production and DNA damage. GSSG, 4-HNE, and DNA damage induce the production of interleukin-8, a proinflammatory cytokine that attracts and activates neutrophils. Activated neutrophils also generate ROS. Pollen NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative stress induces mitochondrial ROS generation. These ROS mediated by innate signaling pathways ‘signal 1’ promote the allergic inflammation ‘signal 2’, the classical allergic inflammation pathway. APC, antigen-presenting cell; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Signal 1, as noted above, by itself is not sufficient to induce allergic inflammation [9,10], and requires a boost from additional signals to fully manifest the allergic inflammatory process. One mechanism of induction of allergic inflammation is recruitment of ROS-generating neutrophils [17▪▪]. Decreasing ROS generation from recruited neutrophils disrupting gp91phox NADPH oxidase also reduces allergic airway inflammation [17▪▪]. Another mechanism of augmentation of signal 1 is modulation of mitochondrial complexes and mitochondrial proteins by pollen NADPH oxidase. Thus, RWPE-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial ROS generation modulates allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) by modulating signal 1 [18] (Fig. 1). Exposure to RWPE induces oxidative damage to ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein II in mitochondria, and increases H2O2 release from complex III [18]. Small interfering RNA suppression of ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein II enhances RWPE-induced allergic inflammation and mucin production in the airway [18]. Likewise, studies utilizing inhibitors of mitochondrial respiratory chain provide evidence supporting a role of mitochondrial respiratory chains in signal 1 and subsequent allergic inflammation induced by RWPE [18]. Thus, mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, complex II inhibitor, and inhibitor of the Qo site of complex III all suppress ROS generation in epithelial cells and histamine release from mast cells [18–20]. Furthermore, antimycin A, which inhibits the Qi site of complex III inhibitor, enhances production of mitochondrial ROS, and modulates allergic airway inflammation [18]. Other studies on experimental asthma have provided additional evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction, such as reduction of cytochrome c oxidase activity in lung mitochondria and reduction in the expression of subunit III of cytochrome c oxidase in bronchial epithelium in asthma [21]. Change and increase of mitochondria in the airway have been observed in patients with asthma [22,23]. Together, these observations support the hypothesis that mitochondria are associated with the pathogenesis of allergic asthma.

One report evaluating pollen NADPH oxidase in birch pollen extract suggested that these oxidases do not contribute to allergic sensitization, inflammation, and AHR [24]. The difference between the results of earlier published literature and this report could be because of the type of pollen antigen (RWPE in earlier studies vs. birch pollen extract) studied, the route of sensitization (intraperitoneal injection in earlier studies vs. intratracheal injection in the birch pollen study), or the technology utilized to destroy intrinsic pollen NADPH oxidases: 72°C for 30min in the earlier studies [9] to gently destroy enzyme activity vs. 95°C for 15 min in the birch pollen study [24], which can theoretically induce structural changes in proteins at a high temperature. To resolve this controversy, additional research is required to define the role of pollen NADPH oxidases from different pollens and elucidate their contribution to allergic sensitization and allergic inflammation. Ideally, these studies should utilize better technology than heat treatment to destroy the activity of this oxidase.

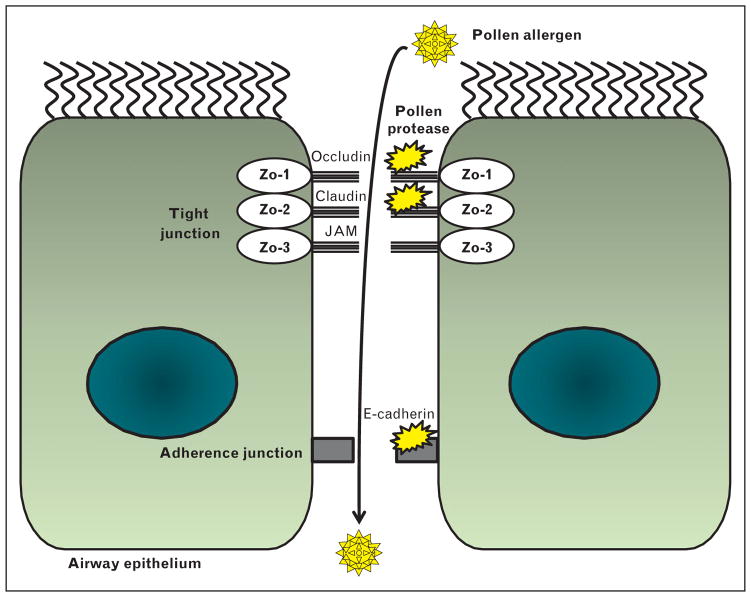

POLLEN PROTEASES DAMAGE EPITHELIAL TIGHT JUNCTION PROTEIN

A considerable body of evidence has demonstrated that modulation of airway epithelial barrier function by pollens contributes to the pathogenesis of allergic disorders [25–27]. The loss of epithelial tight junction function could theoretically allow pollen allergens to pass into the airway and drive the sensitization and antigen responses [28]. Thus, the ability of some pollen proteases to change the integrity of airway epithelial cells is likely to facilitate transfer of pollen antigens to underlying dendritic cells, leading to sensitization and inflammation (Fig. 2). Thus, pollen diffusates from Olea europaea, Dactylis glomerata, Cupressus sempervirens, and Pinus sylvestris have proteases with serine or aminopeptidase activity that increase the transepithelial permeability [29]. Pollen diffusates from ragweed, white birch, and Kentucky blue grass have proteolytic activity that damages tight junctions in human airway epithelial cells [30]. Interestingly, timothy grass pollen extracts do not change the tight junction on human epithelial cells, suggesting that they are allergenic because of alternative factors [31]. Because barrier function in the airway epithelium is already impaired in patients with asthma [26,27], additional damage by pollen proteases is likely to further worsen this damage.

FIGURE 2.

Proteases in pollens degenerate the epithelial tight and adherence junction. Pollen protease increases the permeability of the airway epithelium by disruption of tight and adherence junction. Pollen allergens can go through airway epithelium easily because of the loss of epithelial barrier function. JAM, junctional adhesion molecules; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

INNATE RESPONSES INDUCED BY AQUEOUS POLLEN EXTRACT PROTEINS AUGMENT TH2 CYTOKINE SECRETION

Increasing evidence has shown that aqueous pollen extract proteins (APEP) can modulate immune responses by activating hematopoietic cells. Birch aqueous pollen extract proteins (B-APEP) can facilitate CXCL12-mediated migration of dendritic cells [32], and stimulate Th2 chemokine CCL22 and CCL17 production, but not Th1 chemokine CXCL10 or CCL5 production [32]. B-APEP enhances lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced Th2 chemokine production, but suppresses LPS-induced Th1 chemokine production [32]. B-APEP also inhibits the maturation of 6-sulfo LacNAc1 dendritic cells (slanDCs) that stimulate Th1 cytokines [33]. By contrast, slanDCs exposed to low-molecular-weight nonprotein factors in aqueous birch pollen extracts fail to stimulate Th1 cell induction [33]. Like B-APEP, Betula alba APEP also suppresses LPS-induced interleukin-12 production from dendritic cells [34]. These results imply that APEPs modulate dendritic cell function and stimulate Th2 polarization.

Additional evidence for the role of APEP comes from in-vivo studies. B. alba APEPs modulate allergic inflammation in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized mice. Antigen-specific T cells from the mice challenged with OVA together with B. alba APEP demonstrate increased secretion of Th2 cytokines, but reduced interferon (IFN)-γ secretion, compared with antigen-specific T cells from the mice challenged with OVA alone [34]. In addition, B. alba APEP induces a shift inimmune response toward Th2 differentiation, as demonstrated using OVA-specific DO11.10 T cells [34].

POLLEN-DERIVED LIPIDS STIMULATE INNATE AND ALLERGIC RESPONSES

Investigators have profiled the pollen lipid from allergenic plant species by gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy and identified more than 106 lipid molecular species including fatty acids, n-alkanes, fatty alcohols, and sterols [35▪▪]. Among these lipids, several lipid compounds stimulate dendritic cells and induce differential cytokine production patterns [35▪▪]. Pollen-derived E1-phytoprostanes (PPE1) in B. alba L. aqueous pollen extracts activate dendritic cells, leading to Th2 skewing [36]. PPE1 inhibit LPS-induced secretion of interleukin-12 p70 and interleukin-6 from dendritic cells and slanDCs [33,34]. They modulate dendritic cell function via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-dependent nuclear factor-κB activation. These events lead to suppression of interleukin-12 production from dendritic cells [37]. PPE1 inhibits LPS-induced increase in CCL5, CXCL10, and CCL22 expression in dendritic cells. These dendritic cells attract more Th2 cells [32]. The total lipid fractions from O. europaea pollen can activate dendritic cells and stimulate invariant natural killer T cells [38]. Thus, pollen lipid affects the function of a variety of cells by modulating dendritic cell function.

Increasing evidence suggests that pollen lipids can also directly stimulate other hematopoietic cells. The cypress pollen lipid components, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine, are recognized by T cells and cause Th2-dominant response associated with increased Th2 cytokine production [39]. Gamma delta T cells from allergic patients recognize pollen-derived phosphatidylethanolamine in a CD1d-dependent manner, leading to secretion of Th1 and Th2 cytokine and enhancement of immunoglobulin E (IgE) production [40]. Natural killer T cells stimulated with lipid compounds from several pollens induce secretion of distinct patterns of cytokine production [35▪▪]. The lipid mediators in aqueous pollen extracts from Phleum pratense and B. alba pollen recruit and activate eosinophils [41]. Likewise, aqueous pollen extracts and lipid mediator from P. pratense L. and B. alba L. pollen induce migration and activation of polymorphonuclear granulocytes [42]. These studies indicate that pollen lipids can activate a variety of cells and stimulate allergic inflammation.

INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSES INDUCED BY POLLEN EXTRACTS

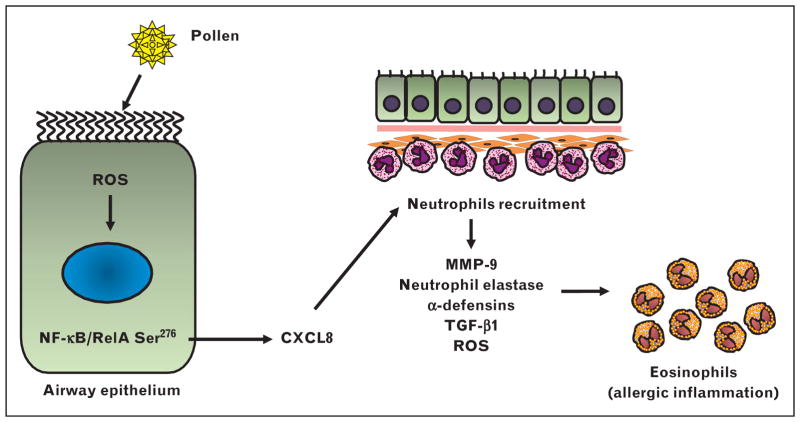

Airway and corneal epithelium play critical roles in host mucosal immunity, and provide the first line of defense system against constant environmental insults. Prior studies [16,43,44] have shown that challenge with allergenic extracts induce an early wave of neutrophil recruitment. Microarray analysis has revealed that Phl p 1, a major timothy grass pollen allergen, increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokine in airway epithelial cells [45]. Interleukin-8 is a major neutrophil chemoattract chemokine. Phl p 1 induces interleukin-8 secretion from human airway epithelial cells independently of its protease activity [46]. Likewise, timothy grass pollen extracts induce interleukin-8 secretion in bronchial epithelial cells from healthy volunteers and patients with severe asthma [31]. Microarray analysis of the innate responses induced by timothy grass pollen extract induces a similar inflammatory cytokine expression, including interleukin-8 secretion from airway epithelial cells [47]. Likewise, Parietaria judaica pollen extract can directly stimulate interleukin-8 secretion from human lung microvascular endothelial cells [48]. We have demonstrated that toll-like receptor (TLR)4 is essential for pollen allergenic extracts to induce nuclear factor-κB and CXCR signaling-linked neutrophil recruitment [49▪▪]. Suppression of these pollen extract–induced innate responses by disrupting TLR4 or treating mice with a CXCR2 inhibitor also inhibits induction of allergic airway inflammation [49▪▪]. These data suggest that TLR4 mediates the innate response of the airway epithelium by inducing CXCR chemokines that recruit neutrophils and drive allergic inflammation (Fig. 3). How neutrophils contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma is still unclear. A variety of factors in neutrophils, such as matrix metalloproteinase 9 [50], neutrophil elastase [51,52], α-defensins [53,54], transforming growth factor-β1 [55], and ROS [56], however, can mediate AHR, allergic inflammation, and airway remodeling.

FIGURE 3.

Neutrophil recruitment by pollens is important for induction of allergic inflammation. Pollen allergen activates nuclear factor-κB, leading to the production of CXCL8 in airway epithelium. Activated neutrophils recruited by CXCL-8 facilitate subsequent allergic inflammation by releasing MMP-9, neutrophil elastase, α-defensins, TGF-β1, and ROS. 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta 1.

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is considered a key epithelium-derived cytokine for allergic airway inflammation and remodeling [57–59]. Short ragweed pollens can trigger allergic conjunctivitis through TLR4-dependent TSLP secretion in sensitized mice [57]. Challenge of sensitized mice with Cupressus arizonica pollen allergen, nCup a 1, increases the expression of TSLP in the lungs of sensitized mice [60]. Likewise, interleukin-33 secretion is higher in airway epithelial cells from allergic patients, and can facilitate induction of allergic inflammation and airway contraction [61–64]. Inhaled cypress pollen nCup a 1 induces secretion of interleukin-33 and increases ST2 expression on dendritic cells migrating to the lung. These dendritic cells skew Th2 polarization through CD4 Th cells [60].

Dendritic cells are crucial cells that connect innate immunity to adaptive immunity, and contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic disorders by regulating Th1/Th2 polarization. Because dendritic cells are resident in the surface of airway epithelium and underlying lamina propria, pollens most likely stimulate dendritic cells directly. RWPE activates dendritic cells through oxidative stress and NF-E2-related factor 2-mediated signaling [65]. These activated dendritic cells suppress secretion of interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 [65]. Likewise, Cupressaceae pollens suppress LPS-induced interleukin-12 secretion from dendritic cells [66]. Pollen grains induce secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from dendritic cells independently of TLR4 [66]. Uptake and presentation of pollen allergens Bet v 1 and Phl p 1 by dendritic cells can activate autologous naïve T lymphocytes [67]. Taken together, these studies indicated that pollensmodulate the function of dendritic cells and skew their immune response toward Th2 by suppressing Th1 cytokine secretion.

INNATE IMMUNE RECEPTORS MODULATE POLLEN-INDUCED INFLAMMATION

TLR4 is an innate immune receptor for a variety of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns. The role of TLR4 in the mechanism of asthma and allergy has been investigated. TLR4 gene variants have been associated with sensitization and bronchial asthma [68–71]. Atopic children have impaired LPS-induced TLR4 signaling [72]. TLR4 signaling suppresses allergic airway inflammation and AHR via upregulation of nitric oxide synthase 2 activity [73]. LPS–TLR4 signaling modifies the Th2 response depending on the dose of LPS [74,75]. With regard to antigens, house dust mite allergen signals via TLR4 signaling in airway structural cells and induces Th2 skewing in amurine asthmamodel [76]. Der p 2, which is a major component of house dust mite, shows structural homology with MD2 and enhances allergic inflammation by facilitating TLR4 signaling, even at low LPS conditions [77]. The relation between TLR4 and pollens, however, is not well understood. Our preliminary studies have suggested that RWPE can induce TLR4-dependent effects on airways such as induction of ROS, CXCL1/2 secretion, and neutrophil recruitment [49▪▪]. RWPE-induced neutrophilic inflammation can itself promote allergic airway inflammation by further increasing ROS levels in airways [49▪▪]. Likewise, challenge with short ragweed pollen in sensitized mice facilitates the allergic conjunctivitis through TLR4 pathway [57]. TLR4 enhance the birch pollen extract-induced allergic inflammation, but is not required for the AHR [24]. By contrast, coadministration of protollin, a mucosal adjuvant composed of TLR2 and TLR4 ligands, with birch pollen allergen extract suppressed allergic inflammation through the induction of inducible costimulatory molecule-expressing CD4 T cells [78]. One report indicated that pollen-induced TLR4 signaling could be due to LPS because contamination of Ryegrass with LPS increased Th1 and Th2 effector T cells, and decreased induction of CD4+ Foxp3 high regulatory T-cells [79]. Par37 (37-amino acid peptide) in the major allergen of the Parietaria pollen Par j 1 contains an LPS-binding region and inhibits LPS-induced interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IFN-γ production [80]. Thus, carefully constructed studies are required to investigate and define the contribution of TLR4 to pollen-induced innate and allergic immune response.

C-type lectin dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 1-grabbing nonintegrin (dendritic cell-SIGN) (CD209) is known as antigen uptake receptor. Bermuda grass pollen allergens BG60 and Cyn d 1 were recognized by both dendritic cell-SIGN and dendritic cell-SIGN receptor [81]. BG60 led to the secretion of TNF-α through dendritic cell-SIGN [81]. Alveolar macrophages from rat bind and phagocytose pollen starch granules through C-type lectin and integrin receptors and result in an upregulation in inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA and the production of nitric oxide [82].

THERAPEUTIC EFFICACY OF STRATEGIES THAT MODULATE INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSES TO POLLENS

Recently, allergen immunotherapy has been the standard treatment for the patients with pollen allergy with poor control in spite of conventional pharmacotherapy and avoidance of allergens. The problems of allergen immunotherapy are low levels of efficacy and the prolonged duration required to demonstrate efficacy. To address these problems, the innate immune response of DNA has been utilized to modulate response of pollens. TLR9-stimulating unmethylated CpG motifs in immunostimulatory DNA sequences stimulate Th1 innate immune responses [83]. Amb a 1-immunostimulatory phosphorothioate oligonucleotide conjugate (AIC) is well tolerated [84]. Early studies [83,85] demonstrated that AIC reduced the clinical symptoms during the second ragweed season in the patients with allergic rhinitis sensitized to ragweed. Furthermore, AIC suppressed the seasonal increase of Amb a 1-specific IgE antibody [83], generation of interleukin-4 mRNA-positive cells, and recruitment of eosinophils. By contrast, it increased IFN-γ mRNA-positive cells in nasal mucosa after allergen challenge [85]. Despite these earlier reports indicating benefit of AIC, two large multicenter studies, TOLAMBA and Dynavax Allergic Rhinitis TOLAMBA Trial (DARTT), failed to demonstrate significant benefit of immunostimulatory sequence (ISS) conjugates in the primary efficacy endpoint [86].

Another TLR-stimulating strategy that has been explored is tyrosine-absorbed specific allergoids enhanced with the TLR4-stimulating adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A to potently boost an immune response in patients with allergic rhinitis [87]. The study demonstrated strong stimulation of allergen-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG)1 and IgG4. A large study [86] of over 1000 patients of allergoid-monophosphoryl lipid A, however, demonstrated a slight benefit of only about 13% over the placebo arm.

In addition to stimulating TLR9 or TLR4 by ISS DNA or allergoid-monophosphoryl lipid A, several other strategies are being developed to modulate innate immune response to pollens. Oral immunotherapy utilizing Cry j1 conjugated with galactomannan in Japanese cedar pollinosis that demonstrated its safety, clinical efficacy, and ability to stimulate allergen-specific serum IgG4 and interleukin- 10 secretion from peripheral blood mononuclear cells [88]. Conjugation of Bet v 1 to the crystalline surface layer proteins derived from Gram-positive eubacteria changed the production of interleukin-12 from T cells [89]. Finally, a completely different approach from these chemically induced conjugates is the creation of chimeric proteins by DNA shuffling of tree pollen allergens; these conjugates demonstrated low allergenicity and high immunogenicity [90]. Future studies will have to evaluate the efficacy of these new strategies.

Because TLR9 and TLR4 conjugate strategies have not been satisfactory in humans, novel technologies are being developed to monitor the events in vivo following exposure to pollens to better understand the events in vivo. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated to Phl p5a and an optical probe (Alexa647) can interact with IgE antibodies and are suitable for monitoring by magnetic resonance imaging and flow cytometry [91]. Likewise, DNA aptamers CJ2-06 against the Cry j 2 can be useful for biosensing applications [92].

CONCLUSION

The innate immune responses to APEPs, pollen-derived proteases, lipids, and NADPH oxidases are complex, and lead to allergic inflammation. An important area of research has been to understand how these rapid innate immune responses induced by pollen components stimulate allergic inflammation. These components recruit neutrophils, modulate dendritic cell functions, and induce Th2 polarization and allergic inflammation. Some clinical studies have shown that modulation of innate immune response to pollens with TLR9- and TLR4-stimulating conjugates is well tolerated and has clear immunological effects, but is not very effective in primary clinical endpoints. Further investigations are required to clarify the innate immune mechanisms induced by pollens and its components. Future studies should evaluate modulating TLR4/MD2 function with a reagent other than allergoid-monophosphoryl lipid A. Another approach could be inhibiting CXCR2-mediated recruitment of activated neutrophils that drive allergic airway inflammation [49▪▪,93]. Because innate immune responses to pollens occur rapidly within minutes, clarification of these early mechanistic events is likely to lead to development of strategies and drugs that will prevent initiation of allergic sensitization in naïve patients, and block induction of allergic inflammation in sensitized patients at the start of the inflammatory process. This approach will be fundamentally different from strategies that directionally force immune response such as pollen-ISS or lipid A conjugates, or inhibit later established allergic events such as blocking Th2 cytokines or their receptors.

KEY POINTS.

Pollens have aqueous pollen extract proteins, proteases, lipids, and NADPH oxidases that stimulate innate immune responses.

These innate immune responses recruit neutrophils, modulate dendritic cell functions, induce Th2 polarization, and stimulate allergic inflammation.

A two-signal hypothesis has been proposed for induction of pollen-induced allergic inflammation: ‘signal 1’, consisting of innate signaling pathways activated by pollen-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS), boosts ‘signal 2’, the classical pathway of antigen presentation to T cells that impart immunological specificity to the immune response.

Multicenter clinical studies have shown that modulation of innate immune response to pollens by conjugating pollen proteins with DNA or lipids can stimulate TLR9 and TLR4 and induce clear immunological effects, and is well tolerated in humans, but is not very effective in primary clinical endpoints.

To address these somewhat disappointing results with the use of pollen conjugates, a careful study of the early innate signaling events induced by pollens is required, and is likely to provide vital clues for the development of novel treatment and prevention strategies for pollen-mediated allergic diseases.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

The present work was supported by NAID P01 AI062885-06, NIEHS RO1 ES18948, NHLBI Proteomic Center, N01HV00245, NIEHS T32 ES007254, and Leon Bromberg Professorship at UTMB.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no specific conflicts of interest regarding the content of the present article.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

- 1.Bowler RP, Crapo JD. Oxidative stress in allergic respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:349–356. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratziou C, Rovina N, Makris M, et al. Breath markers of oxidative stress and airway inflammation in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2008;21:949–957. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comhair SA, Bhathena PR, Dweik RA, et al. Rapid loss of superoxide dismutase activity during antigen-induced asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;355:624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworski R, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Murray JJ, et al. Assessment of oxidant stress in allergic asthma by measurement of the major urinary metabolite of F2-isoprostane, 15-F2t-IsoP (8-iso-PGF2alpha) Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:387–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson JD, Herzenberg LA, Vasquez K, Waltenbaugh C. Glutathione levels in antigen-presenting cells modulate Th1 versus Th2 response patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan RC, Wang M, Li N, et al. Pro-oxidative diesel exhaust particle chemicals inhibit LPS-induced dendritic cell responses involved in T-helper differentiation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csillag A, Boldogh I, Pazmandi K, et al. Pollen-induced oxidative stress influences both innate and adaptive immune responses via altering dendritic cell functions. J Immunol. 2010;184:2377–2385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsue H, Edelbaum D, Shalhevet D, et al. Generation and function of reactive oxygen species in dendritic cells during antigen presentation. J Immunol. 2003;171:3010–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boldogh I, Bacsi A, Choudhury BK, et al. ROS generated by pollen NADPH oxidase provide a signal that augments antigen-induced allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2169–2179. doi: 10.1172/JCI24422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, Choudhury BK, et al. Effect of pollen-mediated oxidative stress on immediate hypersensitivity reactions and late-phase inflammation in allergic conjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharajiya N, Choudhury BK, Bacsi A, et al. Inhibiting pollen reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-induced signal by intrapulmonary administration of antioxidants blocks allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruzel ML, Bacsi A, Choudhury B, et al. Lactoferrin decreases pollen antigen-induced allergic airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. Immunology. 2006;119:159–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chodaczek G, Saavedra-Molina A, Bacsi A, et al. Iron-mediated dismutation of superoxide anion augments antigen-induced allergic inflammation: effect of lactoferrin. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2007;61:268–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calhoun WJ, Reed HE, Moest DR, Stevens CA. Enhanced superoxide production by alveolar macrophages and air-space cells, airway inflammation, and alveolar macrophage density changes after segmental antigen bronchoprovocation in allergic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:317–325. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders SP, Zweier JL, Harrison SJ, et al. Spontaneous oxygen radical production at sites of antigen challenge in allergic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1725–1733. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lommatzsch M, Julius P, Kuepper M, et al. The course of allergen-induced leukocyte infiltration in human and experimental asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17▪▪.Sevin CM, Newcomb DC, Toki S, et al. Deficiency of gp91phox inhibits allergic airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:396–402. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0442OC. This interesting manuscript shows the importance of ROS generated by the major NADPH oxidase in neutrophils in induction of allergic airway inflammation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguilera-Aguirre L, Bacsi A, Saavedra-Molina A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction increases allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:5379–5387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chodaczek G, Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, et al. Ragweed pollen-mediated IgE-independent release of biogenic amines from mast cells via induction of mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2505–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui T, Suzuki Y, Yamashita K, et al. Diphenyleneiodonium prevents reactive oxygen species generation, tyrosine phosphorylation, and histamine release in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:742–748. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mabalirajan U, Dinda AK, Kumar S, et al. Mitochondrial structural changes and dysfunction are associated with experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2008;181:3540–3548. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konradova V, Copova C, Sukova B, Houstek J. Ultrastructure of the bronchial epithelium in three children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1985;1:182–187. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950010403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi T, Ishii A, Nakai S, Hasegawa K. Ultrastructure of goblet-cell metaplasia from Clara cell in the allergic asthmatic airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma in vivo. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shalaby KH, Allard-Coutu A, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. Inhaled birch pollen extract induces airway hyperresponsiveness via oxidative stress but independently of pollen-intrinsic NADPH oxidase activity, or the TLR4-TRIF pathway. J Immunol. 2013;191:922–933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heijink IH, Nawijn MC, Hackett TL. Airway epithelial barrier function regulates the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:620–630. doi: 10.1111/cea.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbato A, Turato G, Baraldo S, et al. Epithelial damage and angiogenesis in the airways of children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:975–981. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-189OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao C, Puddicombe SM, Field S, et al. Defective epithelial barrier function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:549–556. e541–e512. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan H, Winton HL, Soeller C, et al. Der p 1 facilitates transepithelial allergen delivery by disruption of tight junctions. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:123–133. doi: 10.1172/JCI5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinhas R, Cortes L, Cardoso I, et al. Pollen proteases compromise the airway epithelial barrier through degradation of transmembrane adhesion proteins and lung bioactive peptides. Allergy. 2011;66:1088–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Runswick S, Mitchell T, Davies P, et al. Pollen proteolytic enzymes degrade tight junctions. Respirology. 2007;12:834–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blume C, Swindle EJ, Dennison P, et al. Barrier responses of human bronchial epithelial cells to grass pollen exposure. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:87–97. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00075612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariani V, Gilles S, Jakob T, et al. Immunomodulatory mediators from pollen enhance the migratory capacity of dendritic cells and license them for Th2 attraction. J Immunol. 2007;178:7623–7631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilles S, Jacoby D, Blume C, et al. Pollen-derived low-molecular weight factors inhibit 6-sulfo LacNAc+ dendritic cells’ capacity to induce T-helper type 1 responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:269–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutermuth J, Bewersdorff M, Traidl-Hoffmann C, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of aqueous birch pollen extracts and phytoprostanes on primary immune responses in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35▪▪.Bashir ME, Lui JH, Palnivelu R, et al. Pollen lipidomics: lipid profiling exposes a notable diversity in 22 allergenic pollen and potential biomarkers of the allergic immune response. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057566. In this interesting manuscript, the authors matched pollen-lipid mass spectra and retention times with the NIST/EPA/NIH mass spectral library, and 106 lipid molecular species including fatty acids, n-alkanes, fatty alcohols, and sterols. Pollen-derived lipid stimulation upregulates cytokines expression of dendritic and natural killer T-cell coculture. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Traidl-Hoffmann C, Mariani V, Hochrein H, et al. Pollen-associated phytoprostanes inhibit dendritic cell interleukin-12 production and augment T helper type 2 cell polarization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:627–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilles S, Mariani V, Bryce M, et al. Pollen-derived E1-phytoprostanes signal via PPAR-gamma and NF-kappaB-dependent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2009;182:6653–6658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abos-Gracia B, del Moral MG, Lopez-Relano J, et al. Olea europaea pollen lipids activate invariant natural killer T cells by upregulating CD1d expression on dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1393–1399. e1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agea E, Russano A, Bistoni O, et al. Human CD1-restricted T cell recognition of lipids from pollens. J Exp Med. 2005;202:295–308. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russano AM, Agea E, Corazzi L, et al. Recognition of pollen-derived phosphatidyl-ethanolamine by human CD1d-restricted gamma delta T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plotz SG, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Feussner I, et al. Chemotaxis and activation of human peripheral blood eosinophils induced by pollen-associated lipid mediators. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traidl-Hoffmann C, Kasche A, Jakob T, et al. Lipid mediators from pollen act as chemoattractants and activators of polymorphonuclear granulocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:831–838. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoskins A, Reiss S, Wu P, et al. Asthmatic airway neutrophilia after allergen challenge is associated with the glutathione S-transferase M1 genotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:34–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0786OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metzger WJ, Richerson HB, Worden K, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage of allergic asthmatic patients following allergen bronchoprovocation. Chest. 1986;89:477–483. doi: 10.1378/chest.89.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roschmann KI, van Kuijen AM, Luiten S, et al. Purified Timothy grass pollen major allergen Phl p 1 may contribute to the modulation of allergic responses through a pleiotropic induction of cytokines and chemokines from airway epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roschmann K, Farhat K, Konig P, et al. Timothy grass pollen major allergen Phl p 1 activates respiratory epithelial cells by a nonprotease mechanism. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1358–1369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roschmann KI, Luiten S, Jonker MJ, et al. Timothy grass pollen extract-induced gene expression and signalling pathways in airway epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:830–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taverna S, Flugy A, Colomba P, et al. Effects of Parietaria judaica pollen extract on human microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49▪▪.Hosoki K, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Boldogh I, et al. Ragweed pollen extract (RWPE)-induces TLR4-dependent neutrophil recruitment that augments allergic airway. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:AB59. This study demonstrated for the first time that pollen-induced TLR4–CXCR2 signaling recruits activate neutrophils to the airways, and these neutrophils facilitate allergic airway inflammation. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park SJ, Wiekowski MT, Lira SA, Mehrad B. Neutrophils regulate airway responses in a model of fungal allergic airways disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:2538–2545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki T, Wang W, Lin JT, et al. Aerosolized human neutrophil elastase induces airway constriction and hyperresponsiveness with protection by intravenous pretreatment with half-length secretory leukoprotease inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1405–1411. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grosse-Steffen T, Giese T, Giese N, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and pancreatic tumor cell lines: the role of neutrophils and neutrophil-derived elastase. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:720768. doi: 10.1155/2012/720768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vega A, Ventura I, Chamorro C, et al. Neutrophil defensins: their possible role in allergic asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakamoto N, Mukae H, Fujii T, et al. Differential effects of alpha- and beta-defensin on cytokine production by cultured human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L508–L513. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00076.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chu HW, Trudeau JB, Balzar S, Wenzel SE. Peripheral blood and airway tissue expression of transforming growth factor beta by neutrophils in asthmatic subjects and normal control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1115–1123. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 1998;92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li DQ, Zhang L, Pflugfelder SC, et al. Short ragweed pollen triggers allergic inflammation through Toll-like receptor 4-dependent thymic stromal lymphopoietin/OX40 ligand/OX40 signaling pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1318–1325. e1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Semlali A, Jacques E, Koussih L, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-induced human asthmatic airway epithelial cell proliferation through an IL-13-dependent pathway. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou B, Comeau MR, De Smedt T, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/ni1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gabriele L, Schiavoni G, Mattei F, et al. Novel allergic asthma model demonstrates ST2-dependent dendritic cell targeting by cypress pollen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:686–695. e687. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamekura R, Kojima T, Takano K, et al. The role of IL-33 and its receptor ST2 in human nasal epithelium with allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:218–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Stolarski B, Kewin P, et al. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barlow JL, Peel S, Fox J, et al. IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in provoking IL-13-producing nuocytes (type 2 innate lymphoid cells) and airway contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rangasamy T, Williams MA, Bauer S, et al. Nuclear erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 inhibits the maturation of murine dendritic cells by ragweed extract. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:276–285. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0438OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kamijo S, Takai T, Kuhara T, et al. Cupressaceae pollen grains modulate dendritic cell response and exhibit IgE-inducing adjuvant activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:6087–6094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noirey N, Rougier N, Andre C, et al. Langerhans-like dendritic cells generated from cord blood progenitors internalize pollen allergens by macropinocytosis, and part of the molecules are processed and can activate autologous naive T lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1194–1201. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Werner M, Topp R, Wimmer K, et al. Heinrich J: TLR4 gene variants modify endotoxin effects on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:323–330. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reijmerink NE, Bottema RW, Kerkhof M, et al. TLR-related pathway analysis: novel gene–gene interactions in the development of asthma and atopy. Allergy. 2010;65:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuertes E, Brauer M, MacIntyre E, et al. Childhood allergic rhinitis, traffic-related air pollution, and variability in the GSTP1, TNF, TLR2, and TLR4 genes: results from the TAG Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:342–352. e342. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kerkhof M, Postma DS, Brunekreef B, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 genes influence susceptibility to adverse effects of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:690–697. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prefontaine D, Banville-Langelier AA, Fiset PO, et al. Children with atopic histories exhibit impaired lipopolysaccharide-induced Toll-like receptor-4 signalling in peripheral monocytes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1648–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodriguez D, Keller AC, Faquim-Mauro EL, et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide signaling through Toll-like receptor 4 suppresses asthma-like responses via nitric oxide synthase 2 activity. J Immunol. 2003;171:1001–1008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan AM, Chen HC, Pochard P, et al. TLR4 signaling in stromal cells is critical for the initiation of allergic Th2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Immunol. 2010;184:3535–3544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eisenbarth SC, Piggott DA, Huleatt JW, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1645–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trompette A, Divanovic S, Visintin A, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shalaby KH, Jo T, Nakada E, et al. ICOS-expressing CD4 T cells induced via TLR4 in the nasal mucosa are capable of inhibiting experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2012;189:2793–2804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mittag D, Varese N, Scholzen A, et al. TLR ligands of ryegrass pollen microbial contaminants enhance Th1 and Th2 responses and decrease induction of Foxp3(hi) regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:723–733. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonura A, Corinti S, Schiavi E, et al. The major allergen of the Parietaria pollen contains an LPS-binding region with immuno-modulatory activity. Allergy. 2013;68:297–303. doi: 10.1111/all.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hsu SC, Chen CH, Tsai SH, et al. Functional interaction of common allergens and a C-type lectin receptor, dendritic cell-specific ICAM3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), on human dendritic cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7903–7910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Currie AJ, Stewart GA, McWilliam AS. Alveolar macrophages bind and phagocytose allergen-containing pollen starch granules via C-type lectin and integrin receptors: implications for airway inflammatory disease. J Immunol. 2000;164:3878–3886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Creticos PS, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, et al. Immunotherapy with a ragweed-toll-like receptor 9 agonist vaccine for allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1445–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simons FE, Shikishima Y, Van Nest G, et al. Selective immune redirection in humans with ragweed allergy by injecting Amb a 1 linked to immunostimulatory DNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1144–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tulic MK, Fiset PO, Christodoulopoulos P, et al. Amb a 1-immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotide conjugate immunotherapy decreases the nasal inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spertini F, Reymond C, Leimgruber A. Allergen-specific immunotherapy of allergy and asthma: current and future trends. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2009;3:37–51. doi: 10.1586/17476348.3.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosewich M, Lee D, Zielen S. Pollinex Quattro: an innovative four injections immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:1523–1531. doi: 10.4161/hv.24631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murakami D, Kubo K, Sawatsubashi M, et al. Phase I/II study of oral immunotherapy with Cry j1-galactomannan conjugate for Japanese cedar pollinosis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jahn-Schmid B, Siemann U, Zenker A, et al. Bet v 1, the major birch pollen allergen, conjugated to crystalline bacterial cell surface proteins, expands allergen-specific T cells of the Th1/Th0 phenotype in vitro by induction of IL-12. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wallner M, Stocklinger A, Thalhamer T, et al. Allergy multivaccines created by DNA shuffling of tree pollen allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Herranz F, Schmidt-Weber CB, Shamji MH, et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated to a grass pollen allergen and an optical probe. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2012;7:435–439. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ogihara K, Savory N, Abe K, et al. DNA aptamers against the Cry j 2 allergen of Japanese cedar pollen for biosensing applications. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;63:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nair P, Gaga M, Zervas E, et al. Safety and efficacy of a CXCR2 antagonist in patients with severe asthma and sputum neutrophils: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1097–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]