Abstract

Rationale:

Acute administration of clozapine (a gold standard of atypical antipsychotics) disrupts avoidance response in rodents, while repeated administration often causes a tolerance effect.

Objective:

The present study investigated the neuroanatomical basis and receptor mechanisms of acute and repeated effects of clozapine treatment in the conditioned avoidance response test in male Sprague-Dawley rats.

Methods:

DOI (2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodo-amphetamine, a preferential 5-HT2A/2C agonist) or quinpirole (a preferential dopamine D2/3 agonist) was microinjected into the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) or nucleus accumbens shell (NAs), and their effects on the acute and long-term avoidance-disruptive effect of clozapine were tested.

Results:

Intra-mPFC microinjection of quinpirole enhanced the acute avoidance disruptive effect of clozapine (10 mg/kg, sc), while DOI microinjections reduced it marginally. Repeated administration of clozapine (10 mg/kg, sc) daily for 5 days caused a progressive decrease in its inhibition of avoidance responding, indicating tolerance development. Intra-mPFC microinjection of DOI at 25.0 (but not 5.0) μg/side during this period completely abolished the expression of clozapine tolerance. This was indicated by the finding that clozapine-treated rats centrally infused with 25.0 μg/side DOI did not show higher levels of avoidance responses than the vehicle-treated rats in the clozapine challenge test. Microinjection of DOI into the mPFC immediately before the challenge test also decreased the expression of clozapine tolerance.

Conclusions:

Acute behavioral effect of clozapine can be enhanced by activation of the D2/3 receptors in the mPFC. Clozapine tolerance expression relies on the neuroplasticity initiated by its antagonist action against 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC.

Keywords: 5-HT2A/2C receptor, D2/3 receptor, medial prefrontal cortex, clozapine, conditioned avoidance response, tolerance

Introduction

As a prototypical atypical antipsychotic drug, clozapine possesses a superior efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia, especially for refractory patients who respond poorly to other antipsychotic medications and patients with a high suicide risk (Kane et al. 1988; McEvoy et al. 2006). The neurobiological mechanisms responsible for its superiority are not known. At the receptor level, clozapine’s mechanism of action is thought to include more potent blockade of serotonin 5-HT2A than of dopamine D2 receptor (Meltzer 2002). However, this property does not distinguish it from other atypical antipsychotic drugs, nor could it be used to explain its therapeutic effects. This is because the unique clinical therapeutic effects of clozapine manifest only after some period of repeated drug treatment, which inevitably induces long-term plastic changes in the brain beyond its acute receptor binding actions. In addition, recent evidence does suggest that the receptor mechanisms underlying the acute effect of clozapine are distinct from that of its chronic effect (Li et al. 2012b; Li et al. 2010). Neuroanatomically, clozapine also does not seem to possess a higher regional specificity than other drugs (Borison and Diamond 1983; Kuroki et al. 1999). Furthermore, the exact neural network upon which clozapine exerts its therapeutic effects has not been elucidated, although the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has been implicated as an important brain region (Ohashi et al. 2000; Pehek and Yamamoto 1994). Overall, it seems difficult to distinguish clozapine from other antipsychotic drugs based on current understandings of its neurobiological mechanisms of action.

Remarkably, at the behavioral level, clozapine can be singled out on the basis of its effect in the conditioned avoidance response (CAR) and phencyclidine (PCP)-induced hyperlocomotion tests, two widely used and validated behavioral measures of antipsychotic activity (Li et al. 2007; Sanger 1985; Wadenberg and Hicks 1999; Zhao et al. 2012). Repeated and intermittent exposures to most antipsychotic drugs (e.g. haloperidol, olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone or asenapine) often lead to a progressive and persistent increase in their ability to suppress avoidance response and PCP-induced hyperlocomotion, known as antipsychotic sensitization. However, clozapine is the only drug that causes a decrease in its ability to do so (termed clozapine tolerance) (Feng et al. 2013; Li et al. 2007; Li et al. 2012a; Li et al. 2010; Qiao et al. 2013; Qin et al. 2013; Zhang and Li 2012). Clozapine tolerance thus represents an interesting form of neuroplasticity. It might be one characteristic effect that distinguishes this drug from other antipsychotic drugs, although its clinical implications are still not clear. We hypothesized that clozapine tolerance may be a unique feature linked to its superior therapeutic efficacy and may reflect its pro-cognitive effect. Therefore, if we could understand the neuroanatomical basis and receptor mechanisms of clozapine tolerance in these preclinical behavioral tests, we may be able to delineate the neurobiological mechanisms responsible for clozapine’s unique therapeutic effect. In the present study, we addressed this issue using a combination of microinjection and pharmacological techniques in the CAR test. We first determined that the mPFC is one critical brain region where clozapine acts to achieve its acute disruptive effect of avoidance, likely through its actions on D2/3 and 5-HT2A/2C receptors (to a lesser extent). Next, we showed that the expression of clozapine tolerance, but not the tolerance induction is dependent on 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC. This study illustrates an interesting dissociated receptor mechanism underlying the acute effect of clozapine and its repeated effect.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (226-250g upon arrival, Charles River, Portage, MI) were housed in pairs in transparent polycarbonate cages (48.3 cm × 26.7 cm × 20.3 cm) and maintained on a 12:12 light/dark schedule. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Room temperature was maintained at 22 ± 1°C with a relative humidity of 45-60%. All procedures were approved by the IACUC at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. All behavioral tests were conducted in the light cycle between 9:00 and 17:00.

Conditioned Avoidance Response Training Procedure

After 5 days of acclimation to the animal facility, rats were first handled and habituated to the custom-built two-compartment shuttle boxes (Med Associates, VT, USA) for 2 days (20 min/day). Over the next two weeks, they were trained to acquire avoidance responding in 10 sessions (1 session/day) (Feng et al. 2013; Li et al. 2010). Each training session consisted of 30 trials and each trial started with a presentation of a conditioned stimulus (CS, 76 dB white noise) for 10 s. If a subject moved from one compartment into the other during the CS presentation, the CS was terminated and an avoidance response was recorded. If the rat did not move across the chambers during the CS, a footshock (unconditioned stimulus, US, 0.8 mA) was immediately delivered to the metal grid floor for a maximum of 5 s. A shuttling response during this period was recorded as an escape. If the rat did not respond during the entire 5 s presentation of the shock, the trial was terminated and the next trial started after an inter-trial interval of 30-60 s. Only those rats (119 out of 156) that reached the training criterion (minimum 70% avoidance response in each of the last two sessions) were used in the subsequent drug tests.

Surgery

One day after the CAR training, rats were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine HCL (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg) (ip), and implanted with bilateral stainless-steel guide cannulas (22 gauge; Plastics One) into the NAs or the mPFC. To avoid the lateral ventricles and to allow a slanted cannula angle aimed at the NAs, the incisor bar was set at 5.0 mm above interaural zero and the coordinates were: anteroposterior (AP) + 3.4 mm, mediolateral (ML) ± 1.0 mm, dorsoventral (DV) − 5.7 mm (Reynolds and Berridge 2001; Richard and Berridge 2011). For mPFC cannulation, the incisor bar was set at − 3.4 mm and the coordinates were: AP + 3.0 mm, ML ± 0.75 mm, DV − 2.2 mm (Paxinos and Watson 2004). All rats were allowed 6-8 days of recovery time before being used in the subsequent drug tests.

Drugs and Microinjections

Clozapine (CLZ, gift from the NIMH drug supply program) was dissolved in 1.0% glacial acetic acid in sterile distilled water and administrated subcutaneously at 10.0 mg/kg in all experiments. This dose of CLZ produces a reliable disruption on avoidance responding and is commonly used in the comparative study of antipsychotic drugs (Feng et al. 2013; Li et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012b; Li et al. 2010; Mead and Li 2009; Qiao et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2009; Zhang and Li 2012; Zhao et al. 2012). It also gives rise to clinically relevant striatal dopamine D2 occupancies in rats (40% − 60%) (Kapur et al. 2003; Wadenberg et al. 2001b). Quinpirole (QUI) and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodo-amphetamine (DOI) (RBI-Sigma, Natick, MA) were dissolved in 0.9% saline (SAL) and were microinjected through 10 μl Hamilton syringes mounted on infusion pumps (Fisher Scientific) via polyethylene tubing (PE 10) attached to a 28-gauge injector (Plastics One), which extended 2.0 or 1.5 mm below the tips of the guide cannulas in the NAs or mPFC, respectively. We tested QUI at 0.0, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 μg/0.5μl/side, and DOI at 0.0, 1.0, 5.0, and 25.0 μg/0.5μl/side, based on previous work showing that these doses are effective at producing behavioral alterations in rats, including prepulse inhibition, impulsive behavior, psychomotor response to cocaine (Beyer and Steketee 2000; Sipes and Geyer 1997; Sotoyama et al. 2011; Wan and Swerdlow 1993; Wischhof et al. 2011). The bilateral microinjection (0.5 μl at 0.5 μl/min) started 1 min after injector insertions, and the injectors remained in place for an additional 1 min post infusion to allow for drug diffusion.

Experiment 1: Effects of intra-NAs or intra-mPFC infusions of QUI or DOI on acute CLZ-induced avoidance disruption

In this experiment, we intended to determine the possible brain sites where CLZ acts to disrupt avoidance responding by centrally infusing a preferential dopamine D2/3 receptor agonist (QUI) or serotonin 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist (DOI) into the NAs or mPFC, two possible sites implicated in the action of CLZ (Atkins et al. 1999; Robertson et al. 1994; Young et al. 1999). After the CAR training, 46 rats were implanted with sterile guide cannulas bilaterally into the NAs or mPFC. After recovery, they were first given a pre-drug retraining session to ensure a high level of avoidance responding (> 70% avoidance response) before drug testing. Four groups of rats were tested: NAs-QUI (n = 12), NAs-DOI (n = 12), mPFC-QUI (n = 11) and mPFC-DOI (n = 11). On the 1st drug test day, rats were injected with CLZ 10 mg/kg. Thirty min later, they were centrally infused with 1 of 4 doses of QUI (0.0, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 μg/0.5μl/side) or DOI (0.0, 1.0, 5.0, and 25.0 μg/0.5μl/side). Rats were then placed in the CAR boxes and tested for avoidance (20 trials) at 45 min and 95 min after the CLZ injection in an attempt to capture the time course of acute action of CLZ. Rats were returned to their home cages during the test interval. Rats remained in their home cages for the following day. On the 3rdday, rats were given a retraining session (30 trials) to return their avoidance response to the pre-drug levels. One day later, the 2nd round of drug testing under a different dose of QUI or DOI was initiated. This 3-day cycle (day 1: drug test, day 2: rest, day 3: retraining) was repeated 4 times until all 4 doses of QUI or DOI had been tested based on a Latin-square design, which provided a random sequence of administered doses in rats.

Experiment 2: Effects of intra-mPFC infusions of DOI during the induction phase on CLZ tolerance

Results from Experiment 1 indicated that the mPFC is one likely brain site where CLZ acts to disrupt avoidance responding. Given the preferential antagonist action of CLZ on 5-HT2A/2C over D2/3, and the finding that D2/3 activation by QUI potentiates rather than diminishes the acute and repeated effects of CLZ (Li et al. 2010), we hypothesized that 5-HT2A/2C receptor activation in the mPFC would decrease CLZ tolerance. In Experiment 2, we tested this hypothesis using a between-subjects design. After the CAR training, 48 rats were implanted with sterile guide cannulas bilaterally into the mPFC. After recovery, they were first given a pre-drug retraining session to ensure a high level of avoidance responding (> 70% avoidance response) before drug testing. Then they were allocated to the following 6 groups (n = 8/group) based on a complete factorial design [2 systemic injection (vehicle (VEH) and CLZ) × 3 central injection (VEH, DOI 5, and DOI 25)]: VEH-SAL, VEH-DOI 5, VEH-DOI 25 and CLZ-SAL, CLZ-DOI 5, CLZ-DOI 25. All rats were first tested under CLZ or vehicle every other day for 5 sessions (30 CS-US trials/session). At the beginning of each test session, rats were first injected with CLZ (10 mg/kg, sc) or sterile water with 1.0% glacial acetic acid (VEH), then centrally infused with SAL, DOI 5 or DOI 25 μg/0.5μl/side into the mPFC 30 min later. 10 min later, they were placed in the avoidance boxes and tested for 30 trials. One day after the 5th CLZ test, all rats were retrained drug-free under the CS-only condition for 1 session and under the CS-US condition for another session the following day to bring their avoidance back to the pre-drug level before the final challenge test to assess the expression of CLZ tolerance (Feng et al. 2013; Li et al. 2012b; Li et al. 2010). On the challenge test, all rats were injected with CLZ 10 mg/kg (sc) and tested for avoidance performance in the CS-only condition (30 trials) 1 h later. No central injection was conducted.

Experiment 3: Effects of intra-mPFC infusions of DOI during the expression phase on CLZ tolerance

Experiment 2 showed that intra-mPFC infusion of DOI (25μg/0.5μl/side) during the tolerance induction phase completely abolished the expression of CLZ tolerance. Experiment 3 examined how activation of prefrontal 5-HT2A/2C receptor by DOI immediately prior to the challenge test would affect the expression of CLZ tolerance. After the CAR training, 25 rats that reached the training criterion were implanted with sterile guide cannulas bilaterally into the mPFC. After recovery, they were first given a pre-drug retraining session to ensure a high level of avoidance responding (> 70% avoidance response) before drug testing. Then they were matched and assigned into 3 groups (n = 8-9/group): VEH-SAL, CLZ-SAL, and CLZ-DOI 25. They were first repeatedly tested for avoidance response under CLZ (10 mg/kg, sc, −45 min) or vehicle every other day for 5 sessions (30 CS-US trials/session). After 2 days of retraining following the last test session, all rats were challenged with CLZ (10 mg/kg, sc) and tested for avoidance response in the CS-only condition (30 trials) 1 h later. Fifteen min before the challenge test, rats in the CLZ-DOI 25 group were centrally infused with DOI 25μg/0.5μl/side into the mPFC, whereas rats in the other groups (the VEH-SAL and CLZ-SAL) were infused with saline.

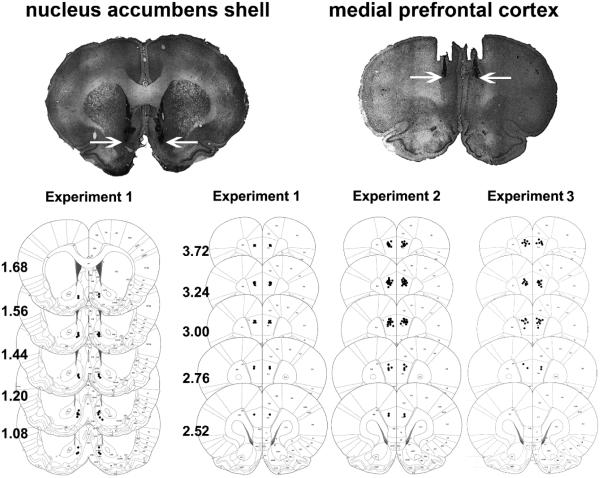

Histology

At the end of behavioral tests, rats were sacrificed and perfused (Gao et al. 2013). Their brains were extracted and the injection sites were verified as previously reported (Gao et al. 2013). The location of injection site was mapped onto a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Watson 2004) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Histological representations of infusion sites and schematic diagrams showing the location of the injector tips in the nucleus accumbens shell (Experiment 1) and medial prefrontal cortex (Experiment 1, 2 & 3). Data are reconstructed from Paxinos and Watson (2004). Numbers to the left of the sections indicate anteroposterior distance from bregma in millimeters. The arrow denotes the infusion placement.

Statistical Analysis

The avoidance data were expressed as the mean percent (i.e. number of avoidances/total number of trials) + SEM. Data from Experiment 1 were analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc LSD pairwise tests and/or one-way repeated measures ANOVA when needed. The two within-subjects factors were “test time” (3 levels: pre-drug day, 45 min and 95 min on the drug day) and “treatment” (QUI, or DOI). In Experiment 2 and 3, avoidance data from the 5 drug tests were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. The between-subjects factor were “CLZ” and “DOI” treatment (Experiment 2), or “DOI” treatment (Experiment 3), while within-subjects factor was “test day”. Data from the challenge tests were analyzed with two-way ANOVA with the between-subjects factors being “CLZ” and “DOI” treatment (Experiment 2), or one-way ANOVA (Experiment 3), followed by post hoc Tukey’s tests. Avoidance data on the pre-drug day in Experiments 2 and 3 were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. For all comparisons, significant difference was assumed at p < 0.05, and all data were analyzed using SPSS version 21. Thirteen rats from all 3 experiments showed either sickness, or cannula failure or misplacement, and they were excluded from data analysis. The final numbers of rats in different groups are indicated in the figure legends.

Results

Experiment 1: Effects of intra-NAs or intra-mPFC infusions of QUI or DOI on acute CLZ-induced avoidance disruption

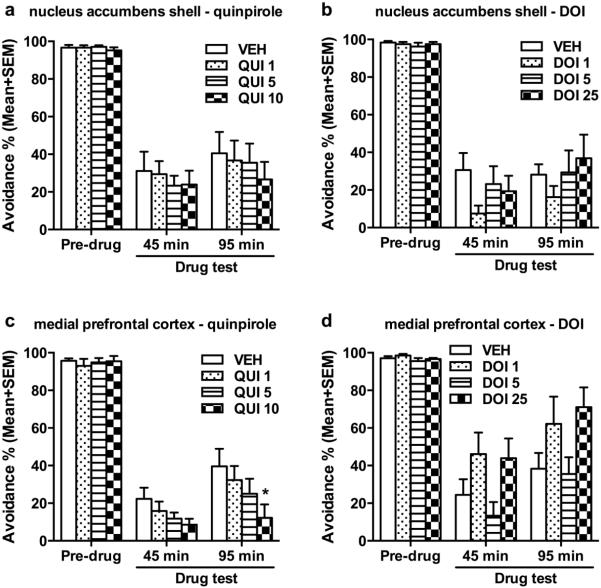

Fig. 2 (a and b) shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug and CLZ test days from rats that received central infusions of QUI or DOI into the NAs. For QUI (Fig. 2a), two-way repeated measure ANOVA showed a main effect of test time (F(2, 16) = 76.549, p < 0.001), but no main effect of QUI (F(3, 24) = 0.992, p = 0.445), nor their interaction (F(6, 48) = 0.600, p = 0.729). Post hoc pairwise tests for test time confirmed that acute CLZ treatment significantly suppressed avoidance response at 45 min and 95 min on the drug test days (both ps < 0.001), compared to the pre-drug day. However, intra-NAs infusion of QUI at all 3 doses (1, 5, 10 μg/0.5μl/side) had no effect on the avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ. For DOI (Fig. 2b), the same analysis showed a main effect of test time (F(2, 14) = 185.846, p < 0.001), but no main effect of DOI (F(3, 21) = 0.992, p = 0.445), nor their interaction (F(6, 42) = 1.224, p = 0.313). Post hoc pairwise tests for test time confirmed that acute CLZ treatment significantly suppressed avoidance response at 45 min and 95 min on the drug test days (both p < 0.001), compared to the pre-drug day. Again, intra-NAs infusion of DOI at all 3 doses (1, 5, 25 μg/0.5μl/side) did not alter the avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ.

Fig. 2.

Effects of microinjection of quinpirole (QUI) at 0, 1, 5 or 10 μg/side or DOI at 0, 1, 5 or 25 μg/side into the nucleus accumbens shell (NAs; a, b) or medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; c, d) on the acute CLZ (10.0 mg/kg, sc)-induced avoidance disruption. n = 9, 8 for NAs − QUI or DOI, and n = 11, 9 for mPFC − QUI or DOI, respectively. Each data point represents the percentage avoidance response (Mean + SEM, number of avoidance responses divided by the total number of trials) made by rats during the pre-drug and the drug test days . Rats received a central infusion 30 min after systematic CLZ injection (10.0 mg/kg, sc), and were tested at 45 min and 95 min after CLZ injection (10 min and 60 min after the central infusion). *p < 0.05 in comparison to the VEH group during each test.

Fig. 2 (c and d) shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug and drug test days from rats that received central infusions of QUI or DOI into the mPFC. For QUI (Fig. 2c), two-way repeated measure ANOVA showed a main effect of test time (F(2, 20) = 256.925, p < 0.001) and a main treatment effect of QUI (F(3, 30) = 3.058, p = 0.043), but no interaction between the two (F(6, 60) = 2.216, p = 0.054). Post hoc pairwise tests for test time confirmed that acute CLZ treatment significantly suppressed avoidance response at 45 min and 95 min on the drug test days (both p < 0.001), compared to the pre-drug day. Intra-mPFC infusion of QUI dose-dependently potentiated the avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ, as post hoc pairwise tests for treatment revealed that CLZ-treated rats centrally infused with QUI at 10 μg/0.5μl/side (p = 0.030), but not at 1 and 5 μg/0.5μl/side (both p > 0.137) had significantly fewer avoidance responses than the vehicle controls. For DOI (Fig. 2d), two-way repeated measure ANOVA showed a main effect of test time (F(2, 16) = 81.247, p < 0.001) and the main effect of DOI (F(3, 24) = 3.156, p = 0.043), and an interaction between the two (F(6, 48) = 2.340, p = 0.046). Post hoc pairwise tests for test time confirmed that acute CLZ treatment significantly suppressed avoidance response at 45 min and 95 min on the drug test days (both p < 0.001), compared to the pre-drug day. The main DOI effect was due to the differences between DOI 5 and DOI 1 (p = 0.033) and between DOI 5 and DOI 25 (p = 0.010). Because of the significant interaction between DOI and test time, one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the group differences at each test time point. There was no significant group difference on the pre-drug day (F(3, 24) = 1.926, p = 0.152). However, there was a marginal significant effect of DOI dose at 45 min (F(3, 24) = 2.760, p = 0.064) and 95 min (F(3, 24) = 2.904, p = 0.056). These findings suggest that acute effect of CLZ can be potentiated by activation of D2/3 receptors in the mPFC.

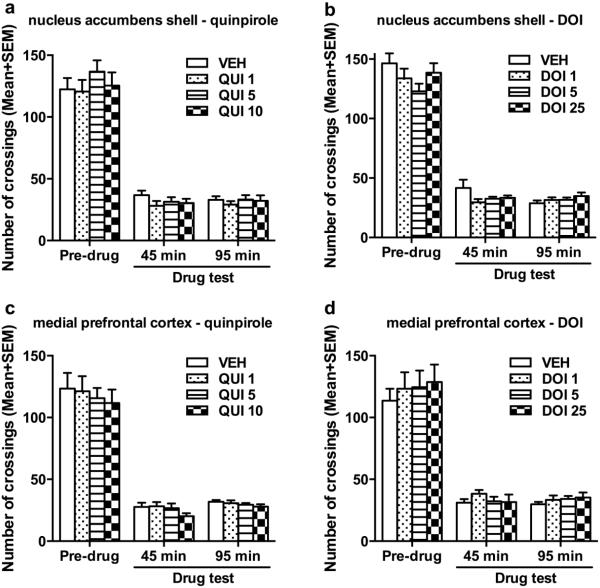

QUI and DOI microinjected into the NAs or mPFC did not affect the CLZ’s suppression of intertrial crossing (Fig. 3), nor escape responding (see Fig. SI for details).). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by post hoc tests revealed that the number of intertrial crossing decreased significantly at 45 min and 95 min (all p < 0.001) on the drug days than the pre-drug day, but infusion of QUI or DOI into NAs or mPFC had no effect. The number of escape responses increased significantly at 45 min and 95 min on the drug day than the pre-drug day (all p < 0.001). These data suggest that the D2/3 receptors and 5-HT2A/2C in the mPFC had no effect on CLZ’s effect on the intertrial crossing and escape responses in this experimental setup.

Fig. 3.

Number of intertrial crossings made by rats on the pre-drug and 5 drug test days. On each drug test day, rats received a central infusion of quinpirole (QUI) at 0, 1, 5 or 10 μg/side or DOI at 0, 1, 5 or 25 μg/side into the nucleus accumbens shell (NAs; a, b) or medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; c, d) 30 min after systematic CLZ injection (10.0 mg/kg, sc), and were tested at 45 min and 95 min after CLZ injection (10 min and 60 min after the central infusion).

Experiment 2: Effects of intra-mPFC infusions of DOI during the induction phase on CLZ tolerance

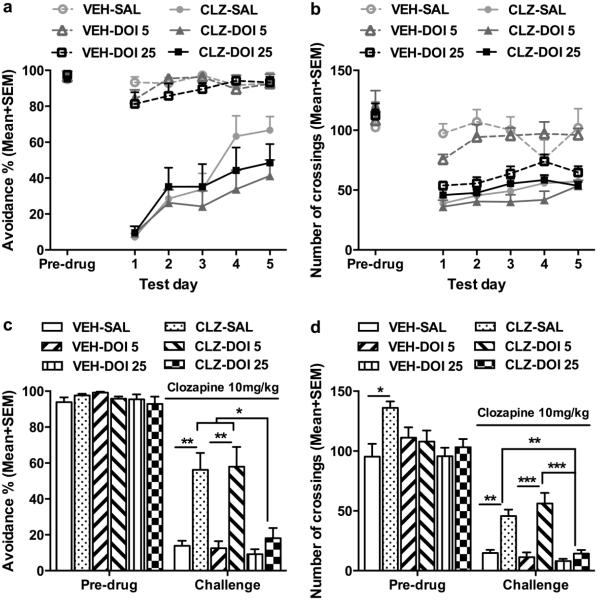

Fig. 4a shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug day and throughout the 5 drug test days. All groups had a high level of avoidance responding on the pre-drug day (one way ANOVA: F(5, 38) = 0.142, p = 0.981). Throughout the 5 drug test days, systemic CLZ treatment significantly decreased avoidance response, but this avoidance suppressive effect was gradually attenuated over time, a clear sign of CLZ tolerance development. Intra-mPFC DOI infusion did not affect the acute effect of CLZ nor the tolerance development. Repeated measures ANOVA (i.e. “CLZ and DOI treatments” as two between-subject factors and “test day” as a repeated within-subjects factor) revealed a main effect of CLZ treatment (F(1, 38) = 184.674, p < 0.001), test day (F(4, 152) = 18.538, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between the two (F(4, 152) = 10.868, p < 0.001), but there was no main effect of DOI (F(2, 38) = 1.058, p = 0.357), no DOI × CLZ interaction (F(2, 38) = 0.735, p = 0.486), nor test day × DOI × CLZ interaction (F(2, 38) = 2.931, p = 0.065). CLZ treatment also decreased the intertrial crossing through the 5 drug test days. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of CLZ treatment (F(1, 38) = 79.63, p < 0.001), DOI (F(2, 38) = 5.102, p = 0.011), test day (F(4, 152) = 4.209, p = 0.003), and a significant interaction of CLZ × DOI (F(2, 38) = 10.473, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). Inspection of Fig. 4b reveals that DOI at 25 μg suppressed the intertrial crossing in a similar manner as did CLZ, suggesting that either activation or suppression of cortical 5-HT2A/2C receptors could decrease motor or motivational suppressing effects of CLZ.

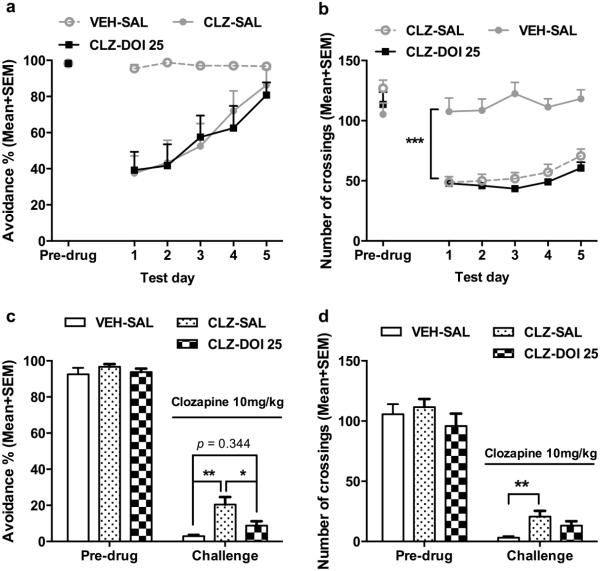

Fig. 4.

Effects of microinjection of DOI into the medial prefrontal cortex during the induction phase of CLZ tolerance. The data represent the percentage avoidance response and number of intertrial crossings (Mean + SEM) made by rats during the pre-drug and 5 drug test days (a, b), and on the retraining day and the challenge test day (c, d). Rats received either systemic vehicle or CLZ (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment in combination with central DOI treatment (0, 5 or 25 μg/side; n= 6, 8, 8 for VEH; n = 7, 8, 7 for CLZ) for 5 test days and were challenged with CLZ (10.0 mg/kg) after two drug-free retraining days. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 in comparison to the corresponding group (c, d).

Fig. 4c shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug day (F(5, 38) = 1.006, p = 0.428) and on the CLZ challenge day. Two-way ANOVA of the avoidance performance on the challenge day revealed a significant effect of CLZ treatment (F(1, 38) = 31.796, p < 0.001), DOI treatment (F(2, 38) = 6.412, p = 0.004), and a significant interaction between the two (F(2, 38) = 4.295, p = 0.021). Subsequent one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s tests revealed that the CLZ-SAL group and CLZ-DOI 5 group made significantly more avoidance responses than the corresponding VEH groups (both ps < 0.001), confirming the CLZ tolerance effect. More importantly, this tolerance effect was absent in the CLZ-DOI 25 group, as it did not differ significantly from the VEH-DOI 25 (p = 0.366), suggesting that intra-mPFC infusion of DOI at 25.0 μg/0.5 μl/side during the induction period of CLZ tolerance completely abolished CLZ tolerance, despite the fact that DOI at this dose had no effect on the day-to-day avoidance disruptive effect of CLZ.

On the intertrial crossing, two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of CLZ treatment (F(1, 38) = 42.013, p < 0.001), DOI treatment (F(2, 38) = 11.451, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between the two (F(2, 38) = 7.552, p = 0.002) on the CLZ challenge day. Subsequent one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests revealed that the CLZ-SAL group (p = 0.004) and CLZ-DOI 5 group (p = 0.001), but not the CLZ-DOI 25 group (p = 0.951) made significantly more crossings than the corresponding VEH groups, indicating a tolerance effect of CLZ on intertrial crossing which was abolished by DOI (at 25 μg/0.5μl/side) (Fig. 4d). Throughout the 5 days of drug treatment, CLZ-treated groups had higher levels of escapes. However, with repeated treatment and the increase of avoidance responses, it was gradually reduced. Intra-mPFC infusion of DOI at all 3 doses had no effect on this behavior (see Fig. SII for details).

Experiment 3: Effects of intra-mPFC infusions of DOI during the expression phase on CLZ tolerance

Fig. 5a shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug day and during the 5 drug test days. We replicated the acute avoidance disruptive effect of CLZ and the developmental process of CLZ tolerance, as confirmed by the repeated measures ANOVA showing a main effect of CLZ treatment (F(2, 21) = 9.091, p = 0.001), test day (F(4, 84) = 15. 438, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between the two (F(8, 84) = 4.293, p < 0.001). Correspondingly, the escape responses were higher in the CLZ treated groups and gradually decreased with the increase of avoidance responses (see Fig. SIII for details).

Fig. 5.

Effects of microinjection of DOI into the medial prefrontal cortex on the challenge day on the expression of clozapine tolerance. The data represent the percentage avoidance response and number of intertrial crossings (Mean + SEM) made by rats during the pre-drug and 5 drug test days (a, b), and on the retraining day and the challenge test day (c, d), respectively. Rats received systemic vehicle or CLZ (10.0 mg/kg, sc) injection for 5 test days and were challenged with CLZ (10.0 mg/kg) after two drug-free retraining days. On the challenge test day, rats received a central infusion of saline (VEH-SAL and CLZ-SAL, n = 8/group) or DOI 25 μg/side (CLZ-DOI 25, n = 8) 15 min before the test. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 in comparison to the corresponding group (c, d).

Fig. 5c shows the mean percentage of avoidance response on the pre-drug day (F(2, 21) = 0.703, p = 0.507) and the CLZ challenge day (F(2, 21) = 9.556, p = 0.001). The CLZ-SAL group had significantly higher avoidance than the VEH-SAL group (p = 0.001), confirming the CLZ tolerance effect. More interestingly, the CLZ-DOI 25 group did not differ from the VEH-SAL group (p = 0.344), but had significantly lower avoidance than the CLZ-SAL group (p = 0.024), suggesting the intra-mPFC infusion of DOI at 25.0 μg/0.5 μl/side prior to the challenge test blocked the expression of CLZ tolerance.

CLZ treatment decreased the number of intertrial crossings through the 5 drug test days (Fig. 5b). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of CLZ treatment (F(2, 21) = 48.273; p < 0.001), test day (F(4, 84) = 6.077; p < 0.001), but no significant interaction between the two (F(8, 84) = 1.402; p = 0.208). Post hoc Tukey’s test confirmed that the VEH-SAL group made significant more crossings than the CLZ-DOI 25 and CLZ-SAL (both p < 0.001). On the CLZ challenge day, the CLZ effect was still significant (F(2, 21) = 5.871, p = 0.009), with the CLZ-SAL group making more crossings than the VEH-SAL group (p = 0.007), confirming the CLZ tolerance effect on intertrial crossing. Interestingly, DOI did not significantly block this tolerance (p = 0.328) (Fig. 5d).

Discussion

Using a pharmacological and microinjection approach, we first demonstrated that the acute avoidance disruptive effect of CLZ could be enhanced by activating the D2/3 receptors in the mPFC and reduced to some extent by activating the prefrontal 5-HT2A/2C receptors. A more important finding is that the expression of CLZ tolerance relies on the neuroplasticity initiated by its antagonist action against 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC. Specifically, in Experiment 1, we showed that intra-mPFC infusion of QUI dose-dependently potentiated the avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ, as CLZ-treated rats centrally infused with QUI at 10 μg/0.5μl/side but not at 1 and 5 μg/0.5μl/side into the mPFC made significantly fewer avoidance responses than the CLZ-treated ones but centrally infused with vehicle. Intra-mPFC infusion of DOI appeared to have an opposite effect as did QUI. It marginally reduced the avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ in this within-subjects design. Both drugs infused into the NAs did not affect this effect of CLZ, thus, whether the NAs is involved in the behavioral effects of CLZ is equivocal and need to be further investigated. Regarding the effects of repeated CLZ administrations, we showed that microinjection of DOI (a preferential 5-HT2A/2C agonist) into the mPFC completely abolished the tolerance expression when it was infused during the induction phase (Experiment 2), and reduced it when it was infused right before the challenge test (Experiment 3). The same central treatment did not affect the acute avoidance suppressive effect of CLZ and the tolerance development. These findings imply that the receptor mechanisms (e.g. primarily D2/3 and 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC) that regulate the acute effect of CLZ are likely different from those (primarily 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC) that modulate CLZ tolerance.

Our previous studies suggest that 5-HT2A receptors appear to be critical for CLZ’s acute disruptive effect on avoidance responding (Li et al. 2012b; Li et al. 2010). In both studies, we found that systemic pretreatment of DOI attenuated acute CLZ-induced disruption of avoidance responding, possibly by activating 5-HT2A receptor in the prefrontal cortex (McOmish et al. 2012). Others also reported that systemic DOI at 10 mg/kg reversed the avoidance disruptive effect of 10 mg/kg CLZ (Browning et al. 2005), and its disruption of maternal behavior (Zhao and Li 2009; 2010), suggesting the reversal effect of DOI on CLZ is quite robust and is a generalized effect. It is thus surprising that central infusion of DOI into the mPFC had only a marginal reversal effect on the acute effect of CLZ. It could mean that our selected doses of DOI or the drug test conditions were not optimal. Since DOI does not differentiate between 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor subtypes, and 5-HT2A and 5- HT2C receptors play opposing roles in various brain functions and psychological processes (Di Giovanni et al. 2000; Di Matteo et al. 2002; Winstanley et al. 2004), including in the CAR (Grauer et al. 2009; Wadenberg and Hicks 1999), it is conceivable that the chosen doses of DOI might have activated both receptors, resulting in a lowered reversal effect of DOI. Alternatively, it could mean that 5-HT2A/2C receptor in other brain regions (e.g. lateral septum, hippocampus or ventral tegmental area) may play a more important role in the regulation of CLZ’s acute effect (Ichikawa et al. 2001b). Finally, because CLZ also has high affinity for adrenergic 1 receptor, muscarinic M1 receptor and histamine H1 receptor and moderate affinity for the D4 and 5-HT6 receptors, its actions on these receptors may also contribute to its acute avoidance-disruptive effect.

Another surprising finding is that microinjection of QUI in the mPFC actually enhanced the acute effect of CLZ, an effect opposite to that of DOI. Our previous systemic studies failed to find such an effect in the CAR (Li et al. 2010) and in maternal behavior (Zhao and Li 2009; 2010). The exact reason for this discrepancy is not clear. One possibility is that QUI might have different effects when it reaches different brain areas. Because systemic QUI administration presumably impacts a broader range of brain areas than central infusion, some of its effects might have canceled each other out, yielding no obvious net effect on CLZ when it is administrated systemically. As to why QUI and DOI produced opposite effects on the acute effect of CLZ, we speculate that activation of D2/3 receptors in the mPFC by QUI may cause a decrease in 5-HT2A/2C receptor-mediated neurotransmission, which could lead to a potentiation of the acute disruption of avoidance of CLZ, as demonstrated in several studies involving other antipsychotic drugs (Wadenberg et al. 2001a; Wadenberg et al. 1998). Furthermore, both receptors are co-localized in the mPFC and they form hetero-5-HT2A/D2 dimers and homo-5-HT2A/5-HT2A dimers (Lukasiewicz et al. 2010), providing a physical basis for their interactions. Therefore, the acute behavioral effect of CLZ is likely mediated by its action on 5-HT2A/2C receptors superimposed by its action on D2/3 receptors.

Consistent with our previous studies, repeated administration of CLZ caused a behavioral tolerance in the CAR test, an effect opposite to behavioral sensitization typically associated with many other antipsychotic drugs. As previously mentioned, we and others have repeatedly demonstrated CLZ tolerance in the CAR test (Feng et al. 2013; Li et al. 2012b; Li et al. 2010; Qiao et al. 2013; Qin et al. 2013; Sanger 1985) and in the PCP-induced hyperlocomotion test (Shu et al. 2014). CLZ tolerance has also been reported in other behavioral domains. For example, in a motor function and attention test, Stanford and Fowler (1997) reported that CLZ-treated rats exhibited tolerance to the drug’s suppressive effect on the amount of time that rats were in contact with a force-sensing target disk. In a fixed ratio 5 lever pressing test, Trevitt et al. (1998) found that acute CLZ treatment significantly suppressed lever pressing but this effect was attenuated with repeated drug administration. Similarly, Varvel et al. (2002) and Villanueva and Porter (1993) also found that repeated dosing with CLZ produced tolerance to the rate-suppressing effects of CLZ in a lever pressing task for food reward. CLZ-induced tolerance has also been observed in a drug discrimination task (Goudie et al. 2007a; Goudie et al. 2007b). Future studies could examine how the interoceptive drug state contributes to CLZ tolerance and what other behavioral mechanisms (e.g. associative learning and contextual control) are involved.

The major contribution of the present study is its identification of the neuroanatomical basis and receptor mechanisms of CLZ tolerance. Previously, we showed that CLZ tolerance development may be mediated by its D2/3 blockade-initiated neural processes, as pretreatment of QUI during the 3-day repeated avoidance test period enhanced the expression of CLZ tolerance in the challenge test (Li et al. 2010). We are currently examining the possible brain regions where QUI may act to modulate CLZ tolerance. In light of the present findings, we will focus on the mPFC as it is one likely target.

In the present study, we revealed that although intra-mPFC infusion of DOI did not affect the acute avoidance disruptive effect of CLZ as well as the tolerance development, it did dose-dependently suppress the expression of CLZ tolerance. This finding highlights the importance of prefrontal 5-HT2A/2C receptors in CLZ tolerance and is also consistent with a recent finding showing that 5-HT2A receptors located on forebrain glutamatergic neurons are critical for the motor suppressive effect of CLZ (McOmish et al. 2012). In that study, McOmish et al. (2012) found that 5-HT2A KO mice lack the locomotor-suppressing response to acute CLZ,suggestingthatthedrug’smotorsuppressioneffect(inwildtypeanimals)is normally mediated by a blockade of 5-HT2A receptors in the prefrontal cortex. This conclusion is strengthened by the observation that restoring 5-HT2A expression in forebrain glutamatergic neurons was sufficient to restore the locomotor-suppressing effect of CLZ. In light of these observations, we can conclude that CLZ’s acute suppression of avoidance responding and intertrial crossing is mediated by its antagonistic action on 5-HT2A receptor on forebrain glutamatergic neurons. Thus, by countering the antagonistic action of CLZ on 5HT2A receptors, intra-mPFC infusions of DOI might block the tolerance to CLZ. Because of the known functional interaction between 5-HT2A receptor and D2 receptor in the mPFC (Ichikawa et al. 2001b), these two receptor mechanisms may diametrically regulate the development/expression of CLZ tolerance. Ichikawa and his colleagues showed that DOI treatment attenuates acute CLZ-induced cortical dopamine release and combined blockade of 5-HT2A and D2 receptors produces a greater increase in dopamine release than that by each alone (Ichikawa et al. 2001a; Ichikawa et al. 2001b). It is thus conceivable that DOI treatment in the mPFC would reduce D2-mediated neurotransmission, possibly via the mPFC to ventral tegmental area pathway (Vazquez-Borsetti et al. 2009) and/or NA pathway, leading to a reduction in CLZ tolerance. This would easily explain why QUI pretreatment potentiates CLZ tolerance (Li et al. 2010), as QUI stimulates D2/3 receptor and increases associated dopamine neurotransmission. Based on the available evidence, we would propose the following hypothesis regarding the neuroreceptor mechanisms of CLZ tolerance: CLZ tolerance is a form of neuroplasticity resulting from CLZ’s dual action on 5-HT2A/2c and D2/3 receptors with a yin–yang-like relation: the magnitude of CLZ tolerance can be increased via stimulating D2/3 receptor (e.g. by QUI) and decreased via stimulating 5-HT2A/2c receptor in the mPFC (e.g. by DOI). This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that repeated CLZ treatment causes an up-regulation of D2 receptor level (Moran-Gates et al. 2006; Tarazi et al. 1998) and a down-regulation of 5-HT2A receptor in the mPFC (Steward et al. 2004).

Finally, we want to comment on the finding that the absolute magnitude of CLZ tolerance appears to be weaker in Experiment 3 than in Experiment 2 (Fig. 4c and 4d versus Fig. 5c and 5d). There are several procedural differences that may contribute to this difference. In Experiment 2, rats were centrally infused with SAL, DOI 5 or DOI 25 μg/0.5μl/side into the mPFC before each CLZ test, whereas in Experiment 3, no such central infusion was done. In Experiment 2, rats were not centrally injected with SAL or DOI before the challenge test, whereas in Experiment 3, they were. In Experiment 2, DOI was administered 5 times, whereas in Experiment 3, it was only administered once. Also, Experiment 2 was run by a female experimenter, and Experiment 3 was run by a male, which could affect rats’ behavior differently, as shown by a recent study (Sorge et al. 2014). All these differences could potentially contribute to the magnitude difference between these two experiments.

Taken together, we demonstrated that acute behavioral effect of CLZ is likely mediated by its actions on the D2/3 and 5-HT2A/2C receptors (to a lesser extent) in the mPFC, whereas its long-term tolerance effect might rely on the neuroplasticity initiated by its antagonist action against 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the mPFC. Because CLZ also has multiple actions on other receptors (e.g. 5-HT1A, D1, D3, H1, M1, 1-noradrenergic, etc.), of which some have been implicated in CLZ tolerance, future studies should expand this line of research by systematically investigating the roles of these receptors in the mediation of CLZ tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Shinn-Yi Chou and Ms. Natashia Swalve for their thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH085635 to Professor Ming Li.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict financial interests.

References

- Atkins JB, Chlan-Fourney J, Nye HE, Hiroi N, Carlezon WA, Jr., Nestler EJ. Region-specific induction of deltaFosB by repeated administration of typical versus atypical antipsychotic drugs. Synapse. 1999;33:118–28. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199908)33:2<118::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer CE, Steketee JD. Intra-medial prefrontal cortex injection of quinpirole, but not SKF 38393, blocks the acute motor-stimulant response to cocaine in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:211–8. doi: 10.1007/s002139900345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borison RL, Diamond BI. Regional selectivity of neuroleptic drugs: an argument for site specificity. Brain Res Bull. 1983;11:215–8. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning JL, Patel T, Brandt PC, Young KA, Holcomb LA, Hicks PB. Clozapine and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway: implications for antipsychotic actions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:617–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Di Mascio M, Esposito E. Preferential modulation of mesolimbic vs. nigrostriatal dopaminergic function by serotonin(2C/2B) receptor agonists: a combined in vivo electrophysiological and microdialysis study. Synapse. 2000;35:53–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200001)35:1<53::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo V, Cacchio M, Di Giulio C, Esposito E. Role of serotonin(2C) receptors in the control of brain dopaminergic function. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:727–34. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng M, Sui N, Li M. Environmental and behavioral controls of the expression of clozapine tolerance: Evidence from a novel across-model transfer paradigm. Behav Brain Res. 2013;238:178–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Li Y, Zhu N, Brimijoin S, Sui N. Roles of dopaminergic innervation of nucleus accumbens shell and dorsolateral caudate-putamen in cue-induced morphine seeking after prolonged abstinence and the underlying D1- and D2-like receptor mechanisms in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:181–91. doi: 10.1177/0269881112466181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ, Cole JC, Sumnall HR. Olanzapine and JL13 induce cross-tolerance to the clozapine discriminative stimulus in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2007a;18:9–17. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328014138d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ, Cooper GD, Cole JC, Sumnall HR. Cyproheptadine resembles clozapine in vivo following both acute and chronic administration in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2007b;21:179–90. doi: 10.1177/0269881107067076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauer SM, Graf R, Navarra R, Sung A, Logue SF, Stack G, Huselton C, Liu Z, Comery TA, Marquis KL, Rosenzweig-Lipson S. WAY-163909, a 5-HT2C agonist, enhances the preclinical potency of current antipsychotics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1433-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J, Dai J, Meltzer HY. DOI, a 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, attenuates clozapine-induced cortical dopamine release. Brain Res. 2001a;907:151–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J, Ishii H, Bonaccorso S, Fowler WL, O'Laughlin IA, Meltzer HY. 5-HT(2A) and D(2) receptor blockade increases cortical DA release via 5-HT(1A) receptor activation: a possible mechanism of atypical antipsychotic-induced cortical dopamine release. J Neurochem. 2001b;76:1521–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:789–96. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, VanderSpek SC, Brownlee BA, Nobrega JN. Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:625–31. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki T, Meltzer HY, Ichikawa J. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on extracellular dopamine levels in rat medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:774–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fletcher PJ, Kapur S. Time course of the antipsychotic effect and the underlying behavioral mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:263–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, He W, Heupel K. Administration of clozapine to a mother rat potentiates pup ultrasonic vocalization in response to separation and re-separation: contrast with haloperidol. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222:385–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Sun T, Mead A. Clozapine, but not olanzapine, disrupts conditioned avoidance response in rats by antagonizing 5-HT2A/2C receptors. Journal of neural transmission. 2012a;119:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0722-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Sun T, Mead A. Clozapine, but not olanzapine, disrupts conditioned avoidance response in rats by antagonizing 5-HT(2A/2C) receptors. J Neural Transm. 2012b;119:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0722-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Sun T, Zhang C, Hu G. Distinct neural mechanisms underlying acute and repeated administration of antipsychotic drugs in rat avoidance conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:45–57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1925-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Davis SM, Meltzer HY, Rosenheck RA, Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis CE, Severe J, Hsiao JK, Investigators C. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:600–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McOmish CE, Lira A, Hanks JB, Gingrich JA. Clozapine-induced locomotor suppression is mediated by 5-HT(2A) receptors in the forebrain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2747–55. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead A, Li M. Avoidance-suppressing effect of antipsychotic drugs is progressively potentiated after repeated administration: an interoceptive drug state mechanism. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:1045–53. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer H. Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology the fifth generation of progress : an official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia ; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Gates T, Gan L, Park YS, Zhang K, Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Repeated antipsychotic drug exposure in developing rats: dopamine receptor effects. Synapse. 2006;59:92–100. doi: 10.1002/syn.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K, Hamamura T, Lee Y, Fujiwara Y, Suzuki H, Kuroda S. Clozapine- and olanzapine-induced Fos expression in the rat medial prefrontal cortex is mediated by beta-adrenoceptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:162–9. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. 5th Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam ; Boston: 2004. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. [Google Scholar]

- Pehek EA, Yamamoto BK. Differential effects of locally administered clozapine and haloperidol on dopamine efflux in the rat prefrontal cortex and caudate-putamen. J Neurochem. 1994;63:2118–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J, Li H, Li M. Olanzapine sensitization and clozapine tolerance: from adolescence to adulthood in the conditioned avoidance response model. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:513–24. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin R, Chen Y, Li M. Repeated asenapine treatment produces a sensitization effect in two preclinical tests of antipsychotic activity. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75C:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Fear and feeding in the nucleus accumbens shell: rostrocaudal segregation of GABA-elicited defensive behavior versus eating behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3261–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03261.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard JM, Berridge KC. Metabotropic glutamate receptor blockade in nucleus accumbens shell shifts affective valence towards fear and disgust. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:736–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GS, Matsumura H, Fibiger HC. Induction patterns of Fos-like immunoreactivity in the forebrain as predictors of atypical antipsychotic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1058–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DJ. The effects of clozapine on shuttle-box avoidance responding in rats: comparisons with haloperidol and chlordiazepoxide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:231–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Q, Hu G, Li M. Adult response to olanzapine or clozapine treatment is altered by adolescent antipsychotic exposure: a preclinical test in the phencyclidine hyperlocomotion model. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:363–75. doi: 10.1177/0269881113512039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipes TE, Geyer MA. DOI disrupts prepulse inhibition of startle in rats via 5-HT2A receptors in the ventral pallidum. Brain Res. 1997;761:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Martin LJ, Isbester KA, Sotocinal SG, Rosen S, Tuttle AH, Wieskopf JS, Acland EL, Dokova A, Kadoura B, Leger P, Mapplebeck JC, McPhail M, Delaney A, Wigerblad G, Schumann AP, Quinn T, Frasnelli J, Svensson CI, Sternberg WF, Mogil JS. Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nature methods. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotoyama H, Zheng Y, Iwakura Y, Mizuno M, Aizawa M, Shcherbakova K, Wang R, Namba H, Nawa H. Pallidal hyperdopaminergic innervation underlying D2 receptor-dependent behavioral deficits in the schizophrenia animal model established by EGF. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford JA, Fowler SC. Subchronic effects of clozapine and haloperidol on rats' forelimb force and duration during a press-while-licking task. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:249–53. doi: 10.1007/s002130050236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward LJ, Kennedy MD, Morris BJ, Pratt JA. The atypical antipsychotic drug clozapine enhances chronic PCP-induced regulation of prefrontal cortex 5-HT2A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Hu G, Li M. Repeated antipsychotic treatment progressively potentiates inhibition on phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion, but attenuates inhibition on amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion: relevance to animal models of antipsychotic drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:334–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi FI, Yeghiayan SK, Neumeyer JL, Baldessarini RJ. Medial prefrontal cortical D2 and striatolimbic D4 dopamine receptors: common targets for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1998;22:693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevitt J, Atherton A, Aberman J, Salamone JD. Effects of subchronic administration of clozapine, thioridazine and haloperidol on tests related to extrapyramidal motor function in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:61–6. doi: 10.1007/s002130050593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel SA, Vann RE, Wise LE, Philibin SD, Porter JH. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on operant responding after acute and repeated administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:182–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0969-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Borsetti P, Cortes R, Artigas F. Pyramidal neurons in rat prefrontal cortex projecting to ventral tegmental area and dorsal raphe nucleus express 5-HT2A receptors. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1678–86. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva HF, Porter JH. Differential tolerance to the behavioral effects of chronic pimozide and clozapine on multiple random interval responding in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadenberg MG, Browning JL, Young KA, Hicks PB. Antagonism at 5-HT(2A) receptors potentiates the effect of haloperidol in a conditioned avoidance response task in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001a;68:363–70. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadenberg ML, Hicks PB. The conditioned avoidance response test re-evaluated: is it a sensitive test for the detection of potentially atypical antipsychotics? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:851–62. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadenberg ML, Hicks PB, Richter JT, Young KA. Enhancement of antipsychoticlike properties of raclopride in rats using the selective serotonin2A receptor antagonist MDL 100,907. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:508–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadenberg ML, Soliman A, VanderSpek SC, Kapur S. Dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy is a common mechanism underlying animal models of antipsychotics and their clinical effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001b;25:633–41. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Swerdlow NR. Intra-accumbens infusion of quinpirole impairs sensorimotor gating of acoustic startle in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:103–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02244341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Theobald DE, Dalley JW, Glennon JC, Robbins TW. 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists have opposing effects on a measure of impulsivity: interactions with global 5-HT depletion. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:376–85. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischhof L, Hollensteiner KJ, Koch M. Impulsive behaviour in rats induced by intracortical DOI infusions is antagonized by co-administration of an mGlu2/3 receptor agonist. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:805–13. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834d6279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CD, Bubser M, Meltzer HY, Deutch AY. Clozapine pretreatment modifies haloperidol-elicited forebrain Fos induction: a regionally-specific double dissociation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:255–63. doi: 10.1007/s002130051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Li M. Contextual and behavioral control of antipsychotic sensitization induced by haloperidol and olanzapine. Behav Pharmacol. 2012;23:66–79. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834ecac4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Li M. The receptor mechanisms underlying the disruptive effects of haloperidol and clozapine on rat maternal behavior: A double dissociation between dopamine D(2) and 5-HT(2A/2C) receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Li M. C-Fos identification of neuroanatomical sites associated with haloperidol and clozapine disruption of maternal behavior in the rat. Neuroscience. 2010;166:1043–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Sun T, Li M. Neural basis of the potentiated inhibition of repeated haloperidol and clozapine treatment on the phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.