Abstract

Accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) causes ER stress, resulting in the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). ER stress and UPR are associated with many neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. The developing brain is particularly susceptible to environmental insults which may cause ER stress. We evaluated the UPR in the brain of postnatal mice. Tunicamycin, a commonly used ER stress inducer, was administered subcutaneously to mice of postnatal day (PD) 4, 12 and 25. Tunicamycin caused UPR in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum of mice of PD4 and PD12, which was evident by the upregulation of ATF6, XBP1s, p-eIF2α, GRP78, GRP94 and MANF, but failed to induce UPR in the brain of PD25 mice. Tunicamycin-induced UPR in the liver was observed at all stages. In PD4 mice, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation was observed in layer II of the parietal and optical cortex, CA1-CA3 and the subiculum of the hippocampus, the cerebellar external germinal layer and the superior/inferior colliculus. Tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation was also shown on PD12 but to a much lesser degree and mainly located in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, deep cerebellar nuclei and pons. Tunicamycin did not activate caspase-3 in the brain of PD25 mice and the liver of all stages. Similarly, immature cerebellar neurons were sensitive to tunicamycin-induced cell death in culture, but became resistant as they matured in vitro. These results suggest that the UPR is developmentally regulated and the immature brain is more susceptible to ER stress.

Keywords: Apoptosis, development, endoplasmic reticulum stress, protein degradation

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a subcellular organelle responsible for posttranslational protein processing and transport. Approximately one third of all cellular proteins are translocated into the lumen of the ER where posttranslational modification, folding and oligomerization occur. The ER is also the site for biosynthesis of steroids, cholesterol and other lipids. Cellular stress conditions, such as perturbed calcium homeostasis or redox status, elevated secretory protein synthesis rates, altered glycosylation levels and cholesterol overloading, can interfere with oxidative protein folding, leading to the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen. This causes ER stress and activates a compensatory mechanism, called the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Wang and Kaufman, 2012; Hetz et al., 2013). UPR attempts to relieve ER stress by two major pathways: the first is to halt the translation of unfolded proteins and enhance endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) of unfolded or misfolded proteins; the second is to increase the expression of molecular chaperones to facilitate proper protein folding (Walter and Ron, 2011; Logue et al., 2013). However, when sustained or severe ER stress surpasses the capacity of UPR, apoptotic cell death occurs (Hetz et al., 2013; Logue et al., 2013).

ER stress and UPR participate in various physiological processes such as lipid and cholesterol metabolism, energy homeostasis, circadian function, cell surface signaling, development and cell differentiation (Rutkowski and Hegde, 2010; Walter and Ron, 2011; Hetz, 2012). ER stress and UPR are also involved in many human diseases and disorders, such as inflammation, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity and cancer (Yamamoto et al., 2010; Wang and Kaufman, 2012; Hetz et al., 2013). ER stress has been shown to play an important role in the pathogenesis of various neurological diseases (DeGracia and Montie, 2004; Scheper and Hoozemans, 2009; Vidal et al., 2011; Xu and Zhu, 2012; Cornejo and Hetz, 2013; Endres and Reinhardt, 2013) and have been implicated in neurodegenerative processes in brain ischemia (Tajiri et al., 2004), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Katayama et al., 2004), Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Chen et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005), Huntington’s disease (HD) (Hirabayashi et al., 2001) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Turner and Atkin, 2006).

The developing brain is particularly susceptible to various environmental insults, e.g., exposure to pollutants, infectious pathogens, heavy metals, drugs, alcohol, physical stress and malnutrition. These environmental factors often cause ER stress and induce UPR (Qian and Tiffany-Castiglioni, 2003; Shin et al., 2007; Hettiarachchi et al., 2008; Ke et al., 2011; Oh et al., 2012; Kitamura, 2013; Pavlovsky et al., 2013; Ji, 2014; Kalinec et al., 2014) and ER stress may account for some of their detrimental effects. However, the mechanisms underlying CNS damage caused by these environmental insults are complex; it may be mediated by the interplay of multiple factors, such as direct toxicity, oxidative stress or disruption of cellular metabolism. To evaluate the impact of ER stress on the developing brain, we need a model system which allows more specific induction of ER stress. Tunicamycin is an N-linked glycosylation inhibitor and is commonly used to induce ER stress experimentally. In this study, we evaluated tunicamycin-induced ER stress in the postnatal development of the mouse brain. We also studied tunicamycin-mediated neuroapoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Tunicamycin and mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit anti-ATF6 antibody was purchased from LifeSpan Biosciences (Seattle, WA). Rabbit anti-Xbp1s antibody was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Rabbit anti-p-eIF2α and cleavedcaspase-3 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Rabbit anti-GRP78 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas). Rat anti-GRP94 antibody was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY 11735). Rabbit anti-MANF antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse antineuronal nuclei (NeuN) antibody was obtained from Millipore Corporate (Billerica, MA). Mouse anti-tubulin, HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse and anti-rat secondary antibodies were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). Biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and ABC kit were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Alexa-488 conjugated anti-rabbit and Alexa-594 conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Ketamine/xylazine was obtained from Butler Schein Animal Health (Dublin, OH). Other chemicals and reagents were purchased either from Sigma Chemical or Life Technologies.

Animals and tunicamycin treatment

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources of the University of Kentucky Medical Center. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines set by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Kentucky. Tunicamycin was administered on postnatal day 4 (PD4), PD12 and PD25. The mice received two subcutaneous injections of tunicamycin at 3 μg/g each and the injections were two hours apart. Tunicamycin was diluted in 150 mM dextrose at a concentration of 0.3 μg/μl. The concentration was selected based on previous studies of tunicamycin injection in adult animals (Krokowski, et al., 2013; Lee, et al., 2012; Puthalakath, et al., 2007; Rosenbaum, et al., 2014; Sammeta and McClintock, 2010; Yamamoto, et al., 2010). Mice in the control group were injected with the same amount of dextrose without tunicamycin. Mice were weighed at 0 and 24 hours after the injection. Twenty four hours after the first injection, the mice were sacrificed, and the brains and livers were dissected and processed for further analysis.

Tissue preparation and immunoblotting

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg/10 mg/kg) and the brain and liver were dissected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored in −80°C. The protein was extracted and subjected to immunoblottting analysis as previously described (Ke et al., 2011). Briefly, tissues were homogenized in an ice cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% SDS, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 5 μg/ml aprotinin. Homogenates were centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatant fraction was collected. After determining protein concentration, aliquots of the protein samples (30 μg) were separated on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with either 5% BSA or 5% nonfat milk in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.05% Tween-20 (TPBS) at room temperature for one hour. Subsequently, the membranes were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After three quick washes in TPBS, the membranes were incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The immune complexes were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). In some cases, the blots were stripped and re-probed with an anti-tubulin antibody. The density of immunoblotting was quantified with the software of Quantity One (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

The procedure for immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been previously described with some modifications (Ke et al., 2011). Briefly, animals were deeply anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine and then intracardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). The brain tissues were removed, post fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for an additional 24 hours and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS until the tissues sunk to the bottom. The tissues were frozen in OCT compound and sectioned at 40 μm in a sagittal plane using a freezing sliding microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Floating sections were incubated in 0.3% H2O2/30% methanol in PBS for 10 min. After washing with PBS, sections were mounted on slides and dried. The slides were then blocked with 5% goat serum and 0.5% TritonX-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. After blocking, the slides were treated with a rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (1:8,000) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, slides were incubated with biotin conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000) for 1 hour at room temperature and followed by washing with PBS. Avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The slides were incubated in the complex for 1 hour at room temperature. After rinsing, the slides were developed in 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) containing 0.003% H2O2 in PBS.

Immunofluorescent staining

The procedure for immunofluorecent staining has been previously described with some modifications (Wang et al., 2007). Briefly, mice were anesthetized and perfused as described above. The brain sections were prepared at 15–20 μm thickness, mounted and dried. After blocking with 5% goat serum and 0.5% TritonX-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, the slides were incubated with a rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody together with anti-NeuN, anti-Iba-1 or anti-GFAP overnight at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor488-conjugated anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG in a dark at room temperature for 1 hour. For examining nuclear morphology, the tissues were incubated with a DNA dye, 4,6-diamidino-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/ml in PBS) for 30 min. After a brief wash, the slides were covered with anti-fade mounting medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and examined/recorded with a fluorescence microscopy (IX81, Olympus).

Culture and treatment of cerebellar granule neurons

Cultures of cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were generated from PD4 C57BL/6J mice using a previously described method (Wang et al., 2007). Briefly, the pups were decapitated under deep anesthesia and cerebella were removed. The cerebella were suspended in 10 ml of 0.25% trypsin solution at 37°C. After incubation for 15 min, an equal volume of solution containing DNase (130 Kunitz units/ml) and trypsin inhibitor (0.75 mg/ml) were added. The tissue was dissociated by trituration, and the cell suspension was mixed with 4% bovine serum albumin and centrifuged. The cell pellet was resuspended in Neurobasal/B27 medium containing B27 (2%), KCL (25 mmol/L), glutamine (1 mmol/L), penicillin (100 units/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cells were plated into poly-D-lysine (50 μg/mL)-coated 96-well plates, and maintained at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2. We have previously used this culture system to investigate the in vitro development of neurons (Chen et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Ke et al., 2009). The neuronal population in this culture system was greater than 95%. After cultured in Neurobasal/B27 medium for 4, 7, or 15 days in vitro (DIV), CGNs were treated with 0.5 μg/ml tunicamycin for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined and quantified by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as previously described (Wang et al., 2007).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were presented as the means ± SD. Statistical comparisons were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. The results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Tunicamycin induces ER stress in the developing mouse brain

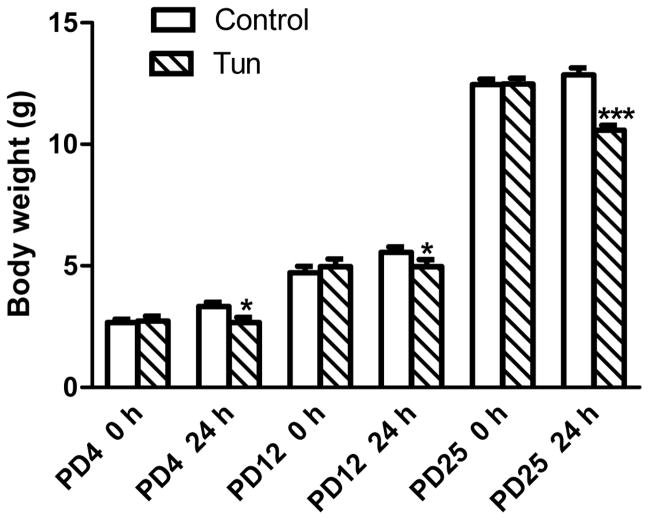

Tunicamycin inhibits protein glycosylation and is a commonly used ER stress inducer. In this study, we injected tunicamycin subcutaneously on the back of mouse pups. Subcutaneous injection was selected over intraperitoneal injection (IP) to avoid the leaking of injected drugs. We did not observe any obvious changes in general behaviors within 24 hours of tunicamycin injection. However, there was a slight but statistically significant reduction of body weight in tunycamycin-treated mice in comparison to control mice (dextrose-treated group) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Effect of tunicamycin on the body weight of postnatal mice.

Mice of postnatal day 4 (PD4), PD12 and PD25 mice were injected subcutaneously with tunicamycin (Tun, 3 μg/g in 150 mM dextrose) or 150 mM dextrose (Control), at 0 and 2 hours as described in Materials and Methods. Body weight was measured at 0 and 24 hours after first injection. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001 in comparison to controls.

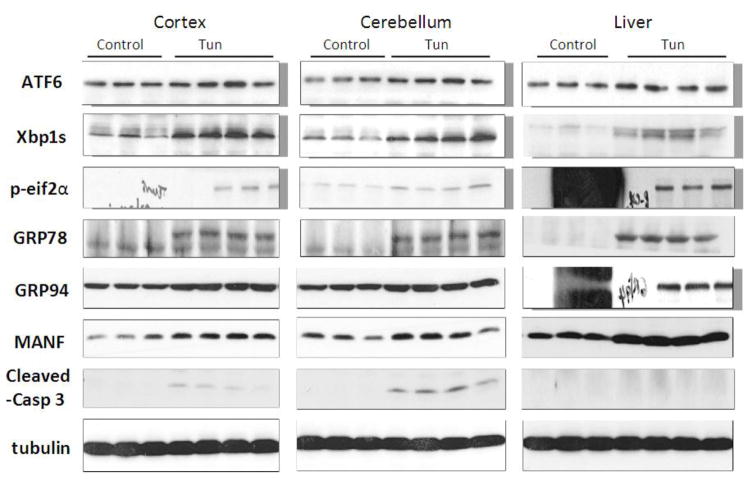

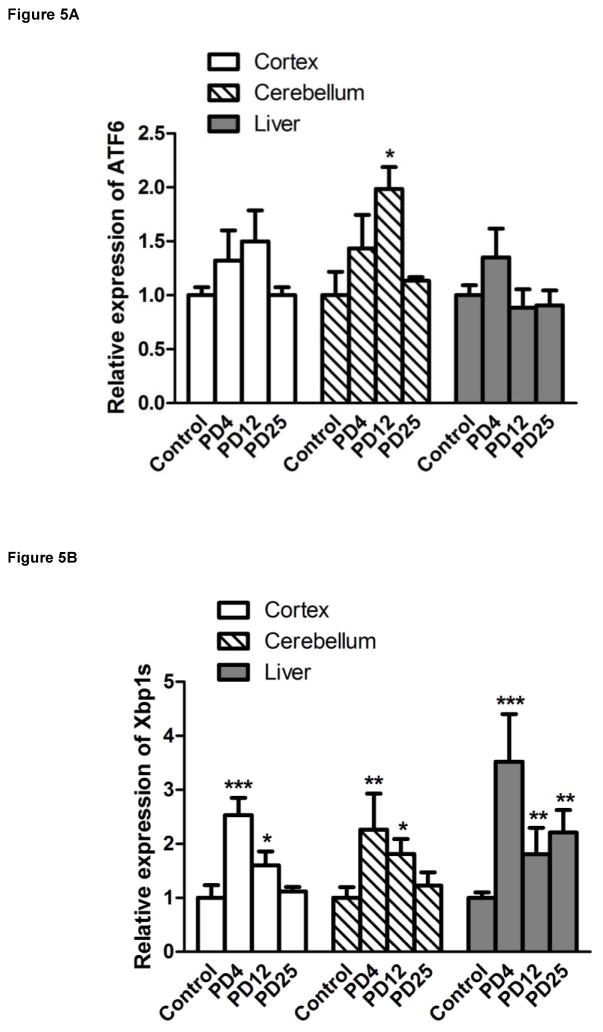

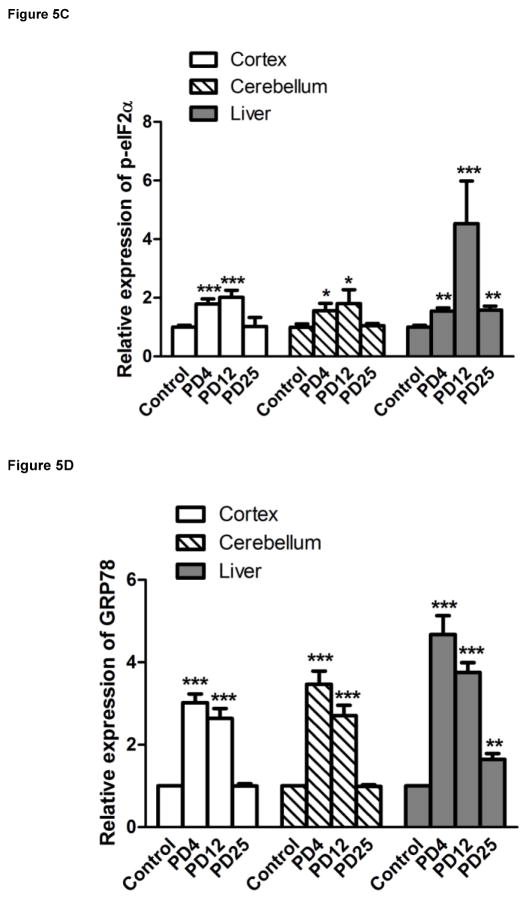

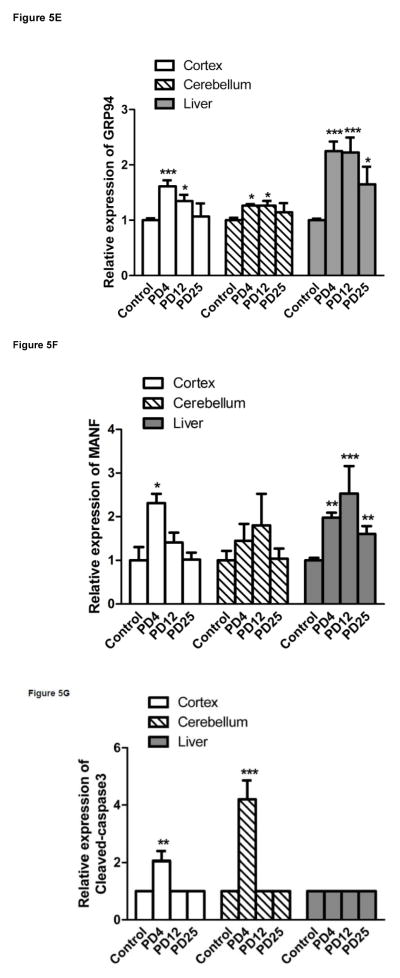

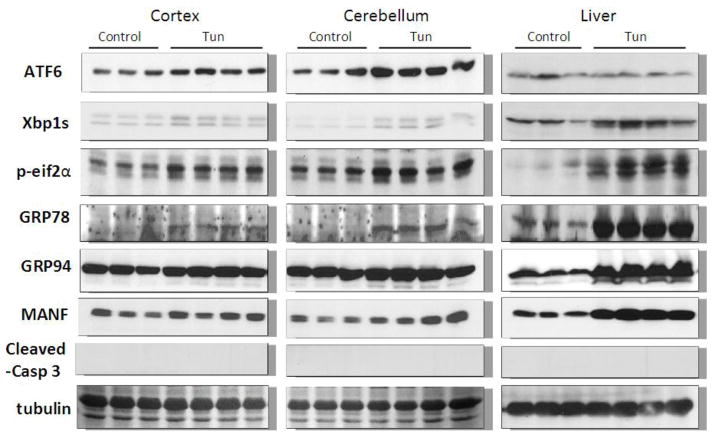

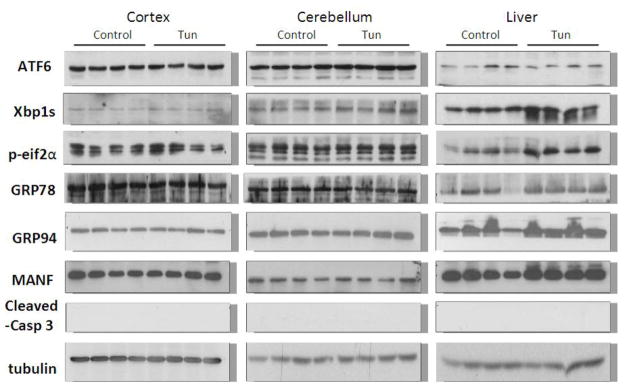

We examined the expression of UPR-related proteins in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum of mouse pups of from postnatal day 4 (PD4) to PD25 by immunoblotting (Figs 2–5). On PD4, tunicamycin induced a significant increase in the expression of XBP1s, p-eIF2α, GRP78/BIP and GRP94 in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. Tunicamycin also significantly increased the expression of MANF in the cortex but not in the cerebellum (Fig. 5F). On PD12, tunicamycin significantly increased the expression of XBP1s, p-eIF2α, GRP78/BIP and GRP94 in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. Tunicamycin increased the expression of processed ATF6 (50 KDa) in the cerebellum but not in the cortex (Fig. 5A). Generally, tunicamycin-induced an increase of UPR markers on PD12 was significantly less or tended to be less than that on PD4. For example, the tunicamycin-induced expression of XBP1s, GRP94 and MANF was significantly less on PD12 than PD4. Tunicamycin did not alter the expression of any of these UPR markers on PD25. The liver is susceptible to ER stress and was used as a positive control for UPR. Tunicamycin significantly increased all UPR markers tested except ATF6. Generally, tunicamycin-induced upregulation of UPR markers on PD25 was lower than that on PD4 and PD12 in the liver.

Figure 2. Effect of tunicamycin on the expression of UPR-related proteins and cleaved caspase-3 in mice of PD4.

Mice of PD4 were injected subcutaneously with tunicamycin (Tun, 3 μg/g in 150 mM Dextrose) or 150 mM dextrose (control) at 0 and 2 hours as described in Materials and Methods. At 24 hours after the first injection, the cerebral cortex, cerebellum and liver was dissected for examining the expression of ATF6, Xbp1s, p-eif2α, GRP78, GRP94, mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF) and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by immunoblotting.

Figure 5. Tunicamycin-induced alterations in UPR-related proteins and cleaved caspase-3.

The expression of ATF6 (A), Xbp1s (B), p-eif2α (C), GRP78 (D), GRP94 (E), MANF (F) and cleaved caspase-3 (G) analyzed immunoblotting quantified by densitometry and normalized to the expression of tubulin. The results are displayed as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 in comparison to controls.

Tunicamycin induces caspase-3 activation in the developing brain

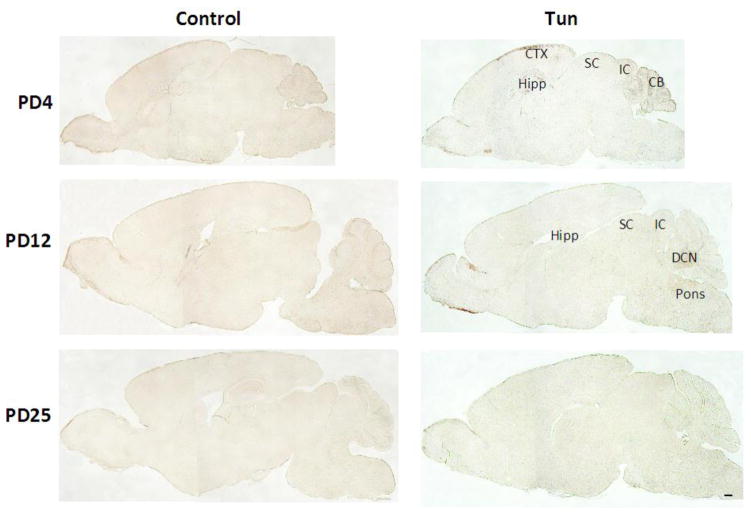

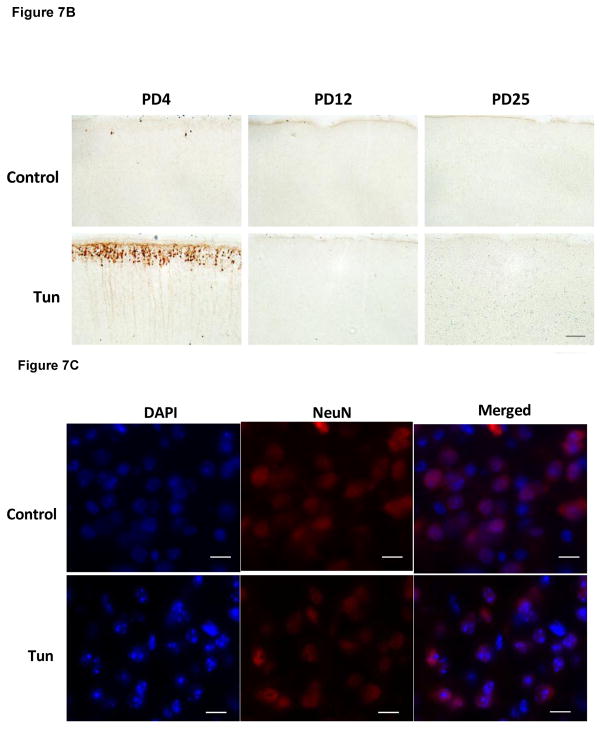

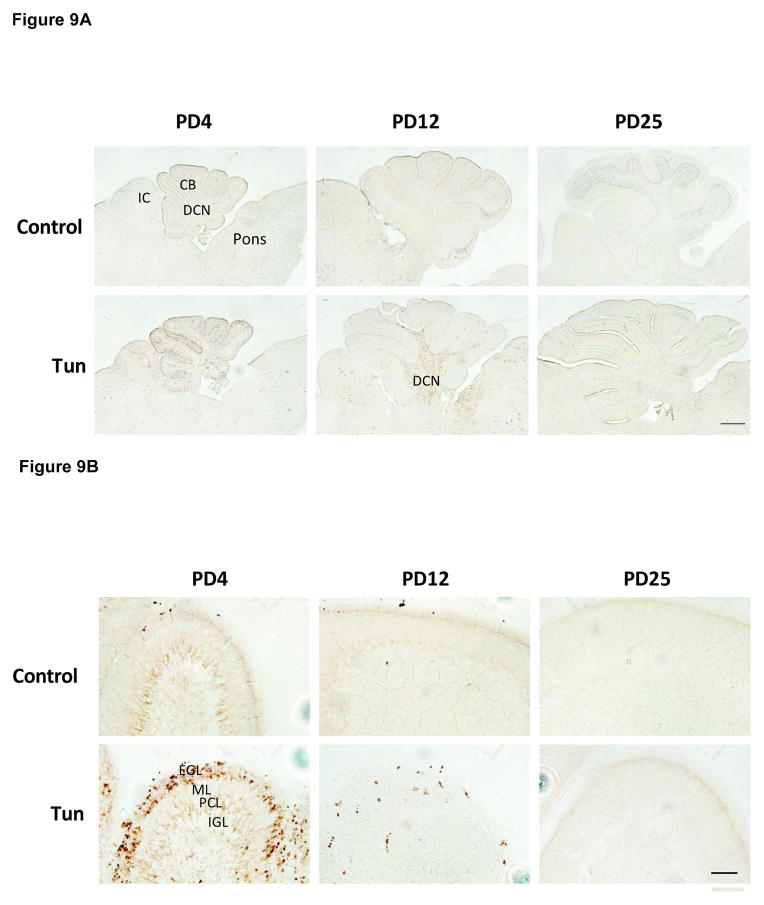

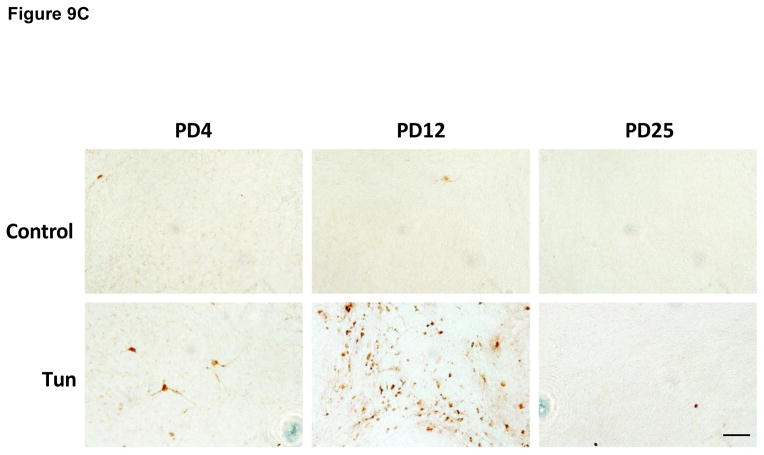

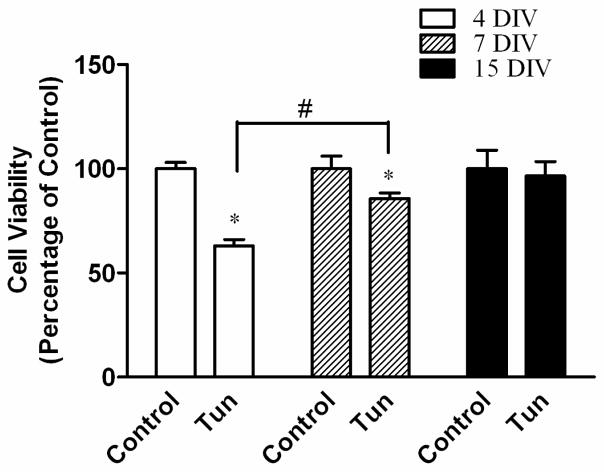

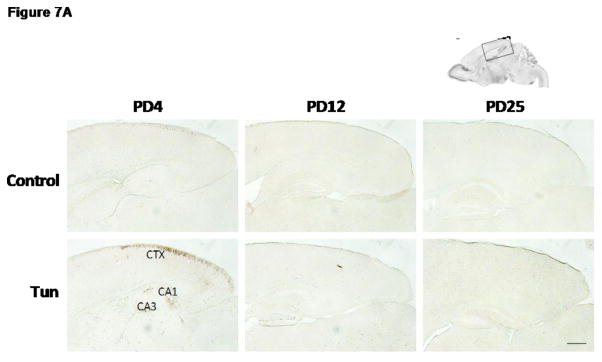

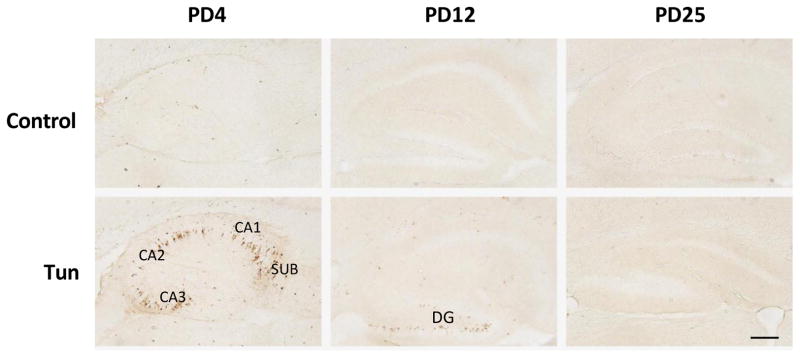

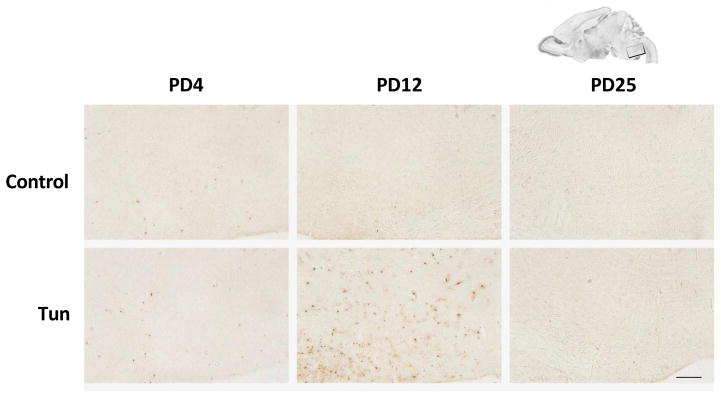

To determine whether tunicamycin caused apoptosis in the developing brain, we examined the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (active) by immunoblotting in the developing brain. We have previously demonstrated that cleaved caspase-3 is a reliable indicator for neuroapoptosis in the developing mouse brain (Liu et al., 2009; Ke et al., 2011; Alimov et al., 2013). Our immunoblotting data indicated that tunicamycin increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3 only in the brain of PD4 mice (Figs. 2 and 5G). In the liver of all ages and the brain of PD12 or later, tunicamycin treatment did not alter the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (Figs 3, 4). Consistent with the immunoblotting data, IHC showed much more intensive immunoreactivity of cleaved caspase-3 in the brain of PD4 following tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 6). The tunicamycin-induced increase in caspase-3 immunoreactivity was observed in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and superior/inferior colliuclus (SC/IC). In the cerebral cortex, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation was mainly concentrated in the layer II of the parietal and optical cortex (Fig. 7A and 7B). We sought to determine the identity of cells undergoing apoptosis following tunicamycin injection and labeled neurons, astrocytes, microglia with anti-NeuN, GFAP and Iba1 antibodies, respectively. With available antibodies, we were unable to double-label NeuN and active caspase-3. We therefore used DAPI to examine nuclear morphology. DAPI showed condensed or fragmented nuclei in tunicamycin-treated animals, indicative of apoptosis. The condensed or fragmented nuclei were observed in NeuN positive cells (Fig. 7C), but not GFAP or Iba1-positive cells (data not shown), indicating that tunicamycin causes apoptosis in neurons but not in astrocytes or microglia. In the hippocampus, tunicamycin induced caspase-3 activation in the subiculum (SUB) and CA1-CA3 of PD4 mice (Fig. 8). In the cerebellum, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation was mainly located in the external germinal layer (EGL) with some caspase-3 positive cells scattered in the internal granule layer (IGL) (Fig. 9).

Figure 3. Effect of tunicamycin on the expression of UPR-related proteins and cleaved caspase-3 in mice of PD12.

Notations are the same as Fig. 1.

Figure 4. Effect of tunicamycin on the expression of UPR-related proteins and cleaved caspase-3 3 in mice of PD25.

Notations are the same as Fig. 1.

Figure 6. Tunicamycin-induced activation of cleaved caspase-3 in the brain of postnatal mice.

Mice of PD4, PD12 and PD25 were injected subcutaneously with tunicamycin (Tun) as described above. Mice were sacrificed 24 hours after the injection. The expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the brain was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) as described in Materials and Methods. CTX, cortex; CB, cerebellum; Hipp, hippocampus; SC, superior colliculus; IC, inferior colliculus; DCN, deep cerebellar nuclei. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Figure 7. Tunicamycin-induced activation of cleaved caspase-3 in the cerebral cortex of postnatal mice.

A: Mice of PD4, PD12 and PD25 were treated as described above and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the cerebral cortex was analyzed by IHC. B: Images of higher magnification show cleaved caspase-3 positive cells in layer II of parietal cortex of PD4 mice. Scale bar = 100 μm. C: Images show condensed or fragmented nuclei (DAPI) in neurons (NeuN-positive) of the parietal cortex following tunicamycin treatment. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 8. Tunicamycin-induced activation of cleaved caspase-3 in the hippocampus of postnatal mice.

Mice of PD4, PD12 and PD25 were treated as described above and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the hippocampus was analyzed by IHC. CA1 and CA3, Cornu Ammonis (CA) 1 and 3; SUB, subiculum; DG, dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 9. Tunicamycin-induced activation of cleaved caspase-3 in the cerebellum of postnatal mice.

A: Mice of PD4, PD12 and PD25 were treated as described above and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the cerebellum was analyzed by IHC. IC; Inferior colliculus; CB, cerebellum; DCN, Deep Cerebellar Nuclei. B: Images of higher magnification show cleaved caspase-3 positive cells in the cerebellar cortex. EGL, external germinal layer; ML, molecular layer; PCL, Purkinje cells layer; IGL, internal granule layer. C: Images of higher magnification show cleaved-caspase 3-positive cells in the DCN. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Interestingly, despite the immunoblotting data shown, no difference was found in the expression of cleaved caspase-3 between control and tunicamycin-treated mice on PD12, the IHC study demonstrated more intense immunoreactivity of active caspase-3 in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus, deep cerebellar nucleus (DCN) and pons (Figs 8, 9 and 10). There was not difference in the immunoreactivity of caspase-3 on PD25 between tunicamycin-treated and dextrose-treated groups. At all developmental stages, tunicamycin did not cause caspase-3 activation in the liver. To verify that immature neurons were more susceptible to tunicamycin-induced cell death, we evaluated the effect of tunicamycin on cultured cerebellar neurons of different maturity. The cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were isolated from the cerebella of mice of PD4 and maintained for 4 days in vitro (DIV), 7 DIV and 15 DIV. As shown in Fig. 11, CGNs of 4 DIV were most susceptible to tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml)-induced cell death, while CGNs of 15 DIV were resistant to tunicamycin-induced cell death. Therefore, the in vitro finding supports our in vivo observation that the susceptibility of neurons to tunicamycin diminishes as the brain matures.

Figure 10. Tunicamycin-induced activation of cleaved casdpase-3 in the pons of postnatal mice.

Mice of PD4, PD12 and PD25 were treated as described above and the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in the pons was analyzed by IHC. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 11. Tunicamycin-induced death of cerebellar neurons in culture.

Cerebellum granule neurons (CGNs) were isolated from mice of PD4 and cultured for 4, 7 or 15 days in vitro (DIV). After that, cells were exposed to tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT as described in the Materials and Methods. The tunicamycin-induced cell death was normalized to age-matched control cultures. Each data point is the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * p<0.05; denotes significant difference from age-matched control cultures. # p<0.05; denotes significant difference between 4 and 7 DIV.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a method to induce UPR in the brain of early postnatal mice by subcutaneous injection of tunicamycin. Tunicamycin has been previously used to induce ER stress in adult mice and rats (Reimertz et al., 2003; Iwawaki et al., 2004; Puthalakath et al., 2007; Sammeta and McClintock, 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Krokowski et al., 2013; Obukuro et al., 2013; Rosenbaum et al., 2014). Intracerebroventricular (ICV) administration of tunicamycin was previously used to evaluate ER stress in the hippocampus and hypothalamus of adult mice (Ono et al., 2012; Brennan et al., 2013; Obukuro et al., 2013). The amount of tunicamycin for ICV administration ranges from 0.04–0.5 μg. The IP injection of tunicamycin was also employed to induce ER stress in various organ systems including the CNS, such as liver, kidney, pancreas, olfactory sensory neurons and cerebral cortex in adult mice and rats (Puthalakath et al., 2007; Sammeta and McClintock, 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Krokowski et al., 2013; Rosenbaum et al., 2014). The concentration of tunicamycin for IP injection ranges from 0.5–10 μg/g. ICV administration of tunicamycin would be ideal to evaluate the effect of tunicamycin on the developing brain. However, developing mouse brain, especially the brain of PD4 is very small and fragile; ICV injection is difficult and the needle penetration causes damage to the brain, confounding the results. IP injection in mouse pups frequently causes leaking and is difficult to ensure the accuracy of drugs being injected. We therefore use subcutaneous (SC) injection to avoid these shortcomings. We have previously used this technique to administrate ethanol to mouse pups and evaluate ethanol-induced ER stress in the developing brain (Ke et al., 2011). We have evaluated various concentrations of tunicamycin (0.5, 1, 2, 3 μg/g) and treatment duration for 8 and 24 hours. The concentration and the duration used in this study (two injections of 3 μg/g, 24 hours) was based on the finding that this concentration causes significant UPR in the brain but does not induce drastic behavioral alteration or death.

Using the paradigm we developed, we demonstrate that tunicamycin induces UPR and region-selective apoptosis in the developing brain. Tunicamycin only induces UPR in the brain of PD4 and PD12 mice, but not in PD25 mice, suggesting that young animals are more susceptible to tunicamycin-induced ER stress in the CNS. Similarly, tunicamycin activates caspase-3 in the brain of PD4 mice and PD12 mice, but not in PD25 mice. Tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation is region-selective. On PD4, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation is mainly observed in cortex layer II of the parietal and occipital cortex. In the hippocampus, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation is shown in CA1-CA3 and SUB. In the cerebellum, tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation is mainly localized in the EGL with some scattered caspase-3 positive cells distributed in the IGL. The mechanisms underlying region-specific activation of caspase-3 are currently unknown. It may be caused by region-related difference in maturation process or neuron subtypes. In future studies, it would be interesting to determine whether tunicamycin-induced activation of caspase-3 and UPR-associated proteins co-localize in the same cell population. It is generally thought that the UPR is a protective response to mitigate ER stress-induced cellular injury. Induction of UPR has been used to alleviate ischemia and hemorrhage-induced brain injury (Yan et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). In this regard, cells that display UPR would be more resistant to tunicamycin-induced cell death and apoptosis markers would possibly be located in neurons deficient of UPR. It is also possible that the high UPR is indicative of intensive ER stress which would induce apoptosis in neurons that the UPR is not sufficient to alleviate ER stress.

For PD12 mice, our immunoblotting analysis fails to reveal tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation, but IHC data shows caspase-3 activation in some specific brain regions, such as the DG of the hippocampus, pons and DCN. This may be due to weak and more confined tunicamycin-induced caspase-3 activation on PD12, so that immunoblotting analysis was not sensitive enough for detection. On PD25, tunicamycin fails to induce caspase-3 activation. This in vivo observation is supported by in vitro study which showed that neurons became resistant to tunicamycin-induced cell death as they matured in culture. Interestingly, tunicamycin did not cause apoptosis in the liver of all stages at the concentration applied, suggesting that the liver has a more efficient protective mechanism and more tolerant to ER stress-induced apoptosis than immature brain.

It is now known that ER stress and UPR play an important role in neural development. In the CNS, the expression of UPR-related proteins is developmentally regulated and ER stress may affect neural development (Zhang et al., 2007; Alimov et al., 2013). ER stress causes aberrant neuronal differentiation and inhibition of dendrite outgrowth in neural stem cells (NSCs) (Kawada et al., 2014). Wolfram Syndrome (WFS) is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, optic nerve atrophy, diabetes insipidus, deafness, and neurological dysfunction leading to death in mid-adulthood. WFS is caused by mutations in the WFS1 gene, which leads to disturbances of ER calcium homeostasis and ER stress-mediated cell death. People with WFS have a pronounced impact on early brain development in addition to later neurodegeneration (Hershey et al., 2012). ER chaperones regulate the survival and vulnerability of Purkinje cells of the cerebellum during development, suggesting that ER stress affects Purkinje cell development (Kitao et al., 2004). Zhang et al (2007) reported that several ER chaperones and UPR related proteins are expressed at higher levels in the embryonic brain and retina than in adult tissues. ER stress-related apoptotic pathway components, such as caspase-7 and caspase-12, are more abundant in embryonic brains than in adult brains. ER stress-like mechanisms may participate in naturally occurring neuroapoptosis and regulate embryonic development of the CNS (Zhang et al., 2007).

Our findings that the developing brain may be more susceptible to ER stress have several implications. First, it suggests that ER stress may be accountable for at least some of the brain damage caused by developmental exposure to pollutants, infectious pathogens, heavy metals, drugs, alcohol, physical stress and malnutrition. For example, the developing CNS is particularly susceptible to ethanol exposure; developmental ethanol exposure induces a spectrum of disorders called fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Ethanol-induced neurodegeneration underlies many of the behavioral deficits observed in FASD (Luo, 2012). Ethanol exposure causes drastic neuroapoptosis in the brain of early postnatal mice (between PD4–12) (Liu et al., 2009; Alimov et al., 2013); this is the same period that mice are sensitive to tunicamycin-induced UPR and caspase-3 activation. Similarly, immature CGNs are sensitive to ethanol-induced cell death but become resistant to ethanol as they mature in vitro (Luo et al., 1997). Ethanol induces ER stress in neurons in vitro and in the developing brain (Ke et al., 2011). It is therefore possible that ER stress contributes to ethanol-induced neurodegeneration in the developing CNS. Second, since tunicamycin-induced UPR and neuroapotosis exhibit spatiotemporal specificity in the developing brain, this offers an excellent model system to investigate the mechanisms of the UPR in neurons. Third, if UPR is a protective mechanism for CNS injury, by systematic analysis of the dosage and the timing of tunicamycin administration, this model system can be optimized to evaluate neuroprotection by UPR in the developing brain.

Highlights.

Tunicamycin caused a development-dependent UPR in the mouse brain.

Immature brain was more susceptible to tunicamycin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Tunicamycin caused more neuronal death in immature brain than mature brain.

Tunicamycin-induced neuronal death is region-specific.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AA015407-09) and National Natural and Science Foundation of China (81100247). This work is also supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development).

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CGNs

cerebellar granule neurons

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

- DAPI

4,6-diamidino-phenylindole

- DCN

deep cerebellar nucleus

- DG

dentate gyrus

- DIV

days in vitro

- EGL

external germinal layer

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- FASD

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- ICV

Intracerebroventricular

- IGL

internal granule layer

- IP

intraperitoneal injection

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NSCs

neural stem cells

- PD

postnatal day

- SC

subcutaneous

- SUB

subiculum

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- WFS

Wolfram Syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alimov A, Wang H, Liu M, Frank JA, Xu M, Ou X, Luo J. Expression of autophagy and UPR genes in the developing brain during ethanol-sensitive and resistant periods. Metabolic brain disease. 2013;28:667–676. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan GP, Jimenez-Mateos EM, McKiernan RC, Engel T, Tzivion G, Henshall DC. Transgenic overexpression of 14-3-3 zeta protects hippocampus against endoplasmic reticulum stress and status epilepticus in vivo. PloS one. 2013;8:e54491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Bower KA, Ma C, Fang S, Thiele CJ, Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3beta) mediates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neuronal death. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2004;18:1162–1164. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1551fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Ma C, Bower KA, Ke Z, Luo J. Interaction between RAX and PKR modulates the effect of ethanol on protein synthesis and survival of neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:15909–15915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo VH, Hetz C. The unfolded protein response in Alzheimer’s disease. Seminars in immunopathology. 2013;35:277–292. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ, Montie HL. Cerebral ischemia and the unfolded protein response. Journal of neurochemistry. 2004;91:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres K, Reinhardt S. ER-stress in Alzheimer’s disease: turning the scale? American journal of neurodegenerative disease. 2013;2:247–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey T, Lugar HM, Shimony JS, Rutlin J, Koller JM, Perantie DC, Paciorkowski AR, Eisenstein SA, Permutt MA Washington University Wolfram Study G. Early brain vulnerability in Wolfram syndrome. PloS one. 2012;7:e40604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi KD, Zimmet PZ, Myers MA. Dietary toxins, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and diabetes. Current diabetes reviews. 2008;4:146–156. doi: 10.2174/157339908784220697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Chevet E, Harding HP. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2013;12:703–719. doi: 10.1038/nrd3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi M, Inoue K, Tanaka K, Nakadate K, Ohsawa Y, Kamei Y, Popiel AH, Sinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Kimura Y, Uchiyama Y, Hori S, Kakizuka A. VCP/p97 in abnormal protein aggregates, cytoplasmic vacuoles, and cell death, phenotypes relevant to neurodegeneration. Cell death and differentiation. 2001;8:977–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwawaki T, Akai R, Kohno K, Miura M. A transgenic mouse model for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med. 2004;10:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nm970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C. New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Alcohol-Induced ER Stress and Liver Diseases. International journal of hepatology. 2014;2014:513787. doi: 10.1155/2014/513787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec GM, Thein P, Parsa A, Yorgason J, Luxford W, Urrutia R, Kalinec F. Acetaminophen and NAPQI are toxic to auditory cells via oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent pathways. Hearing research. 2014;313:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama T, Imaizumi K, Manabe T, Hitomi J, Kudo T, Tohyama M. Induction of neuronal death by ER stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2004;28:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada K, Iekumo T, Saito R, Kaneko M, Mimori S, Nomura Y, Okuma Y. Aberrant neuronal differentiation and inhibition of dendrite outgrowth resulting from endoplasmic reticulum stress. Journal of neuroscience research. 2014;92:1122–1133. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Z, Wang X, Liu Y, Fan Z, Chen G, Xu M, Bower KA, Frank JA, Li M, Fang S, Shi X, Luo J. Ethanol induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in the developing brain. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2011;35:1574–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke ZJ, Wang X, Fan Z, Luo J. Ethanol promotes thiamine deficiency-induced neuronal death: involvement of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2009;33:1097–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura M. The unfolded protein response triggered by environmental factors. Seminars in immunopathology. 2013;35:259–275. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0371-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitao Y, Hashimoto K, Matsuyama T, Iso H, Tamatani T, Hori O, Stern DM, Kano M, Ozawa K, Ogawa S. ORP150/HSP12A regulates Purkinje cell survival: a role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in cerebellar development. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1486–1496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4029-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krokowski D, Han J, Saikia M, Majumder M, Yuan CL, Guan BJ, Bevilacqua E, Bussolati O, Broer S, Arvan P, Tchorzewski M, Snider MD, Puchowicz M, Croniger CM, Kimball SR, Pan T, Koromilas AE, Kaufman RJ, Hatzoglou M. A self-defeating anabolic program leads to beta-cell apoptosis in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced diabetes via regulation of amino acid flux. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:17202–17213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Zheng Z, Mendez R, Ha SW, Xie Y, Zhang K. Pharmacologic ER stress induces non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in an animal model. Toxicology letters. 2012;211:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chen G, Ma C, Bower KA, Xu M, Fan Z, Shi X, Ke ZJ, Luo J. Overexpression of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta sensitizes neuronal cells to ethanol toxicity. Journal of neuroscience research. 2009;87:2793–2802. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue SE, Cleary P, Saveljeva S, Samali A. New directions in ER stress-induced cell death. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death. 2013;18:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Mechanisms of ethanol-induced death of cerebellar granule cells. Cerebellum (London, England) 2012;11:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, West JR, Pantazis NJ. Nerve growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor protect rat cerebellar granule cells in culture against ethanol-induced cell death. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1997;21:1108–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obukuro K, Nobunaga M, Takigawa M, Morioka H, Hisatsune A, Isohama Y, Shimokawa H, Tsutsui M, Katsuki H. Nitric oxide mediates selective degeneration of hypothalamic orexin neurons through dysfunction of protein disulfide isomerase. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12557–12568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0595-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh RS, Pan WC, Yalcin A, Zhang H, Guilarte TR, Hotamisligil GS, Christiani DC, Lu Q. Functional RNA interference (RNAi) screen identifies system A neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2) as a mediator of arsenic-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:6025–6034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Shimazawa M, Ishisaka M, Oyagi A, Tsuruma K, Hara H. Imipramine protects mouse hippocampus against tunicamycin-induced cell death. European journal of pharmacology. 2012;696:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovsky AA, Boehning D, Li D, Zhang Y, Fan X, Green TA. Psychological stress, cocaine and natural reward each induce endoplasmic reticulum stress genes in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2013;246:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, O’Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N, Gotoh T, Akira S, Bouillet P, Strasser A. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Lead-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses in the nervous system. Neurochemical research. 2003;28:153–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1021664632393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimertz C, Kogel D, Rami A, Chittenden T, Prehn JH. Gene expression during ER stress-induced apoptosis in neurons: induction of the BH3-only protein Bbc3/PUMA and activation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. The Journal of cell biology. 2003;162:587–597. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M, Andreani V, Kapoor T, Herp S, Flach H, Duchniewicz M, Grosschedl R. MZB1 is a GRP94 cochaperone that enables proper immunoglobulin heavy chain biosynthesis upon ER stress. Genes & development. 2014;28:1165–1178. doi: 10.1101/gad.240762.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, Hegde RS. Regulation of basal cellular physiology by the homeostatic unfolded protein response. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;189:783–794. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammeta N, McClintock TS. Chemical stress induces the unfolded protein response in olfactory sensory neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1825–1836. doi: 10.1002/cne.22305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper W, Hoozemans JJ. Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control in neurodegenerative disease: the good, the bad and the therapy. Current medicinal chemistry. 2009;16:615–626. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EH, Bian S, Shim YB, Rahman MA, Chung KT, Kim JY, Wang JQ, Choe ES. Cocaine increases endoplasmic reticulum stress protein expression in striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;145:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RM, Ries V, Oo TF, Yarygina O, Jackson-Lewis V, Ryu EJ, Lu PD, Marciniak SJ, Ron D, Przedborski S, Kholodilov N, Greene LA, Burke RE. CHOP/GADD153 is a mediator of apoptotic death in substantia nigra dopamine neurons in an in vivo neurotoxin model of parkinsonism. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;95:974–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Jiang H, Pei Z, Tanaka Y, Morita H, Sawa A, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial cell death pathways mediate A53T mutant alpha-synuclein-induced toxicity. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:3801–3811. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri S, Oyadomari S, Yano S, Morioka M, Gotoh T, Hamada JI, Ushio Y, Mori M. Ischemia-induced neuronal cell death is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway involving CHOP. Cell death and differentiation. 2004;11:403–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Atkin JD. ER stress and UPR in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Current molecular medicine. 2006;6:79–86. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, Caballero B, Couve A, Hetz C. Converging pathways in the occurrence of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in Huntington’s disease. Current molecular medicine. 2011;11:1–12. doi: 10.2174/156652411794474419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:857–867. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang B, Fan Z, Shi X, Ke ZJ, Luo J. Thiamine deficiency induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1045–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Zhu XP. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and prion diseases. Reviews in the neurosciences. 2012;23:79–84. doi: 10.1515/rns.2011.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Takahara K, Oyadomari S, Okada T, Sato T, Harada A, Mori K. Induction of liver steatosis and lipid droplet formation in ATF6alpha-knockout mice burdened with pharmacological endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2975–2986. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Li J, Chen J, Hu Q, Gu C, Lin W, Chen G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is associated with neuroprotection against apoptosis via autophagy activation in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroscience letters. 2014;563:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Szabo E, Michalak M, Opas M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress during the embryonic development of the central nervous system in the mouse. International journal of developmental neuroscience: the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2007;25:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yuan Y, Jiang L, Zhang J, Gao J, Shen Z, Zheng Y, Deng T, Yan H, Li W, Hou WW, Lu J, Shen Y, Dai H, Hu WW, Zhang Z, Chen Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by tunicamycin and thapsigargin protects against transient ischemic brain injury: Involvement of PARK2-dependent mitophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10:1801–1813. doi: 10.4161/auto.32136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]