The question of whether emotional expressions have universal meanings has been at the center of heated debates for many decades (e.g., Ekman, 1994; Russell, 1994). In a recent contribution, Gendron, Roberson, van der Vyver, and Barrett (2014) took issue with our study of emotional vocalizations, in which we claimed to show that some nonverbal sounds reliably communicate emotional states across cultures (Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, & Scott, 2010). In their Study 2, Gendron et al. replicated part of our study (Himba listeners hearing British vocalizations), but analyzed their data in terms of the valance and arousal of the distractors. They found that recognition was not better than chance for most types of distractors and concluded that emotional vocalizations signal valence, but not specific emotions. We welcome their attempted partial replication of our work. Their article has impelled us to reanalyze our original data in more depth. However, given the results of our reanalysis, together with alternative explanations for the results Gendron et al. obtained, we find that their conclusion does not hold.

In our study (Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, & Scott, 2010), participants listened to a series of brief emotion stories. On each trial, they heard two vocalizations: one target (consistent with the story) and one distractor. Our original results, analyzed by emotion but not distractor type, showed cross-cultural recognition of six emotions: Participants selected target vocalizations more often than would be expected by chance. However, three of the four positive emotions included in our study were not reliably recognized by Himba participants listening to British sounds. A fair test of whether recognition performance exceeds chance levels with different types of distractors should include only those emotion categories that participants can recognize at better-than-chance levels, because we made no claims that the other types of vocalizations communicate specific emotional states across cultures. The fact that Gendron et al. (2014) included these emotions in their analysis resulted in a considerable reduction in overall accuracy (as shown by the particularly low accuracy they found for positive emotions). Our reanalysis therefore excluded target vocalizations of the culture-specific signals of triumph, pleasure, and relief.

In our original study, we varied distractors systematically, according to whether their perceived valence was the same as or different from that of the target (valence ratings taken from Sauter, Eisner, Calder, & Scott, 2010). For each emotion, every participant performed two trials with distractors having the same valence as the target and two trials with distractors having the valence opposite that of the target.1 We reanalyzed the data from the 29 Himba participants in our original study who had heard British vocalizations, the part of our study that Gendron et al. (2014) replicated. Each trial was coded for the relationship of the distractor to the target: same valence or different valence. Because surprise is valence neutral, trials in which surprise was either the target or the distractor were removed.

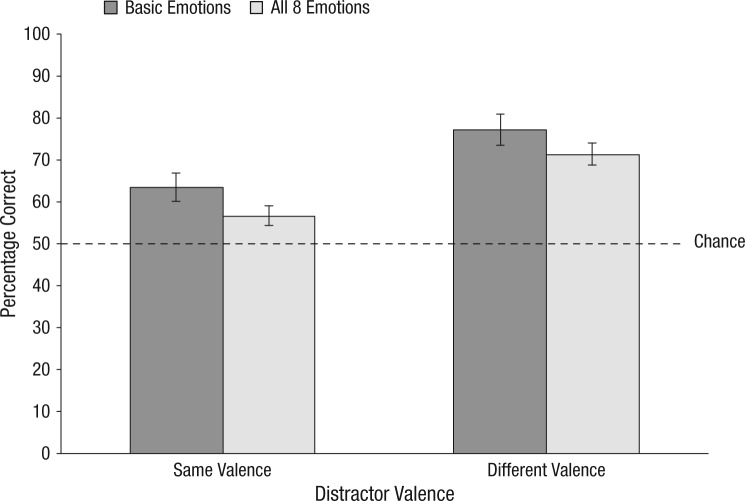

Following Gendron et al. (2014), we calculated the percentage of correct classifications across emotions for each of these trial types (same or different valence), but only for the basic emotions. One-sample t tests comparing performance with chance (50%) revealed that participants’ performance was significantly above chance, both when distractors were of the valence opposite that of the target, t(28) = 7.30, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.36 (mean difference = 27.22, 95% confidence interval, CI, of the difference = [19.58, 34.86]), and when distractors were of the same valence as the target, t(28) = 4.05, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.75 (mean difference = 13.45, 95% CI of the difference = [6.64, 20.26]; see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Himba participants’ recognition performance (percentage correct) for basic emotions and all valenced emotions, for trials on which the distractor and target were of the same valence and trials on which the distractor and target were of different valence. Error bars denote ±1 SEM.

What might underlie the difference in results between our study and the study by Gendron et al. (2014)? As noted, Gendron et al. included culture-specific signals of positive emotions, and this drove down recognition rates. In addition, overall accuracy levels were considerably lower in their study than in ours (mean overall accuracy across all nine emotions in our study was 64.46%; approximate mean overall accuracy based on Fig. 4 in Gendron et al. was 51%). We repeated our analysis including all eight valenced emotions and found that participants’ recognition was again significantly better than chance, both when the distractor and target were of opposite valence, t(28) = 8.30, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.54 (mean difference = 21.37, 95% CI of the difference = [16.09, 26.64]), and when they had the same valence, t(28) = 2.79, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.52 (mean difference = 6.71, 95% CI of the difference = [1.79, 11.63]; see Fig. 1).

An apparent difference in procedure could account for the poor recognition rates Gendron et al. (2014) obtained. In our study, each participant was asked, after each story, how the target person was feeling, in order to ensure that the participant had understood the story correctly. This is because in pilot testing, we found that participants would frequently say that they had understood a story, but were unable to explain it when they were asked to. In our study, therefore, we allowed participants to listen several times to a given recorded story (if needed), until they could explain the intended emotion in their own words, before they proceeded to the experimental trials for that story. The inclusion of a rigorous manipulation check with experimenter verification, rather than reliance on participants’ reports, was thus crucial. Gendron et al. did not report having included this check, indicating only that participants who wished to were allowed to hear the scenarios again. This raises the possibility that some participants in their study may not have correctly understood the intended emotional states.

This may also help to explain the perplexing pattern in the data obtained by Gendron et al. (2014): Recognition was better than chance only when the distractor matched the target in arousal and not in valence, and not when the distractor differed from the target in both arousal and valence. The authors acknowledged that this finding was unexpected; it does not fit with their account that vocalizations communicate valence-based information.

In conclusion, we have presented new analyses that show that nonverbal vocalizations communicate specific emotional states, regardless of the valence of the distractor with which they are presented. Furthermore, we have proposed alternative explanations for the failure of Gendron et al. to find this pattern in their data. We hope that this contribution will serve as a useful addition to the debate on what information can be inferred from emotional expressions cross-culturally.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Narda Schenk for assistance.

In a small number of cases (< 2%), participants completed three trials with distractors of the same valence as the target for one emotion. Note that, if anything, this should have made the task more difficult.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was funded by a Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Veni grant (275-70-033) to D. A. Sauter.

References

- Ekman P. (1994). Strong evidence for universals in facial expressions: A reply to Russell’s mistaken critique. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 268–287. 10.1037/0033-2909.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron M., Roberson D., van der Vyver J. M., Barrett L. F. (2014). Cultural relativity in perceiving emotion from vocalizations. Psychological Science, 25, 911–920. 10.1177/0956797613517239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. A. (1994). Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 102–141. 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter D. A., Eisner F., Calder A. J., Scott S. K. (2010). Perceptual cues in non-verbal vocal expressions of emotion. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63, 2251–2272. 10.1080/17470211003721642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter D. A., Eisner F., Ekman P., Scott S. K. (2010). Cross-cultural recognition of basic emotions through nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 2408–2412. 10.1073/pnas.0908239106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]