Abstract

Background:

Physical activity can improve exercise capacity, quality of life and reduce mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure (HF). Adherence to exercise recommendations in patients with HF is low. The use of exercise games (exergames) might be a way to encourage patients with HF to exercise especially those who may be reluctant to more traditional forms of exercise. No studies have been conducted on patients with HF and exergames.

Aim:

This scoping review focuses on the feasibility and influence of exergames on physical activity in older adults, aiming to target certain characteristics that are important for patients with HF to become more physically active.

Methods:

A literature search was undertaken in August 2012 in the databases PsychInfo, PUBMED, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL. Included studies evaluated the influence of exergaming on physical activity in older adults. Articles were excluded if they focused on rehabilitation of specific limbs, improving specific tasks or describing no intervention. Fifty articles were found, 11 were included in the analysis.

Results:

Exergaming was described as safe and feasible, and resulted in more energy expenditure compared to rest. Participants experienced improved balance and reported improved cognitive function after exergaming. Participants enjoyed playing the exergames, their depressive symptoms decreased, and they reported improved quality of life and empowerment. Exergames made them feel more connected with their family members, especially their grandchildren.

Conclusion:

Although this research field is small and under development, exergaming might be promising in order to enhance physical activity in patients with HF. However, further testing is needed.

Keywords: Exergame, active video game, elderly, exercise, virtual reality

Introduction

Regular daily exercise is recognized as important from both the perspective of primary and secondary prevention in cardiac disease.1 Since heart failure (HF) is a frequent discharge diagnosis it is important to look for any opportunity to improve outcomes. In a recent position paper by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the importance of increased activity and exercise in cardiac patients’ cardiovascular conditions was advocated.2 More specifically, guidelines on the treatment of HF also recommend regular physical activity and structured exercise training, since they improve exercise capacity, quality of life, do not adversely affect left ventricular remodelling and may reduce mortality and hospitalization in patients with mild to moderate chronic HF.2

Physical impairment is described as a significant problem in older adults with HF and exercise capacity in patients with HF is approximately 50–75% of normal age and gender predicted values.3 Several studies have shown that both home-based exercise (often distance walking)4,5 and hospital based6–8 is safe and beneficial for patients with HF. The findings from a meta-analysis (ExTraMatch collaborative) suggested that patients randomized to physical fitness were less likely to be admitted to hospital and had a better prognosis.9 Although the HF-ACTION (Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training) trial did not find significant reductions in the primary end point of all-cause mortality or hospitalization, this study showed a modest improvement in exercise capacity and mental health in patients who exercised. The main limitation in this study was the poor adherence to the prescribed training regimen (only 30% after 3 years).10 Adherence to exercise recommendations in patients with HF is low and low adherence has a negative effect on the clinical outcomes, such as HF readmission and mortality.11 There are many factors that influence adherence in general, and more specifically adherence to exercise. Therefore, it is important to search for alternative approaches to motivate patients with HF to exercise.2,12,13

A scoping review of health game research showed a constant growth over recent years and positive progress towards adapting new technology in specialized health contexts. Most health game studies included physical activity (28%) using so-called exergames (games to improve physical exercise).14 A meta-analysis of energy expenditure (EE) in exergaming showed that playing exergames significantly increased heart rate, oxygen uptake and EE compared to resting, and may facilitate light- to moderate-intensity physical activity promotion.15 The use of these exergames might also be an opportunity for patients with HF to increase their physical activity at home and encourage them to exercise more regularly, especially those who may be reluctant to engage in more traditional forms of exercise, such as going to the gym or taking a walk outside.

A recent review of exergaming for adults with systematic disabling conditions showed that most participants in research with exergames are male and stroke survivors.16

There are no studies on exergaming in patients with HF, and therefore this scoping review was conducted. The purpose of a scoping review is to identify gaps in the existing literature, thereby highlighting where more research may be needed. In contrast to a systematic review, it is less likely to seek to address very specific research questions nor, consequently, to assess the quality of the included studies.17 This scoping review focuses on the feasibility and influence of exergames on physical activity in older adults, aiming to target certain characteristics that are important for patients with HF in order to become more physically active. These characteristics were safety, balance, cognition and experiences.

The research questions to be answered were:

Is exergaming feasible and safe for older adults?

Do exergames influence physical activity in older adults?

Do exergames influence balance in older adults?

Do exergames influence cognition in older adults?

What are the experiences of older adults playing exergames?

Methods

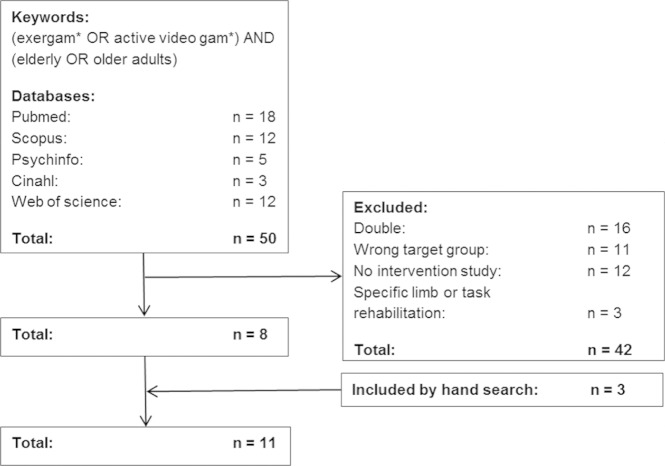

A literature search was undertaken in August 2012 in the international online bibliographic databases PsychINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL. The keywords used were: exergame OR active video game AND elderly OR older adults (Figure 1). In addition to searching the databases, the references of relevant publications were checked. Articles that met the following criteria were included in the review: focusing on the influence of exergames or active video games on older adults’ physical activity (mean age research population ≥ 50 years old) and written in English. Articles were excluded if they were focused on specific limbs or at improving specific tasks or if they did not describe any intervention (e.g. articles on the development of an exergame, descriptive studies). The title and/or abstracts of the studies were scanned for the study objective, study population, exergame platform, training procedure, measurements and main conclusions (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Inclusion of studies in the review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies.

| Author continent | Study objective | Design methodological quality18 | Research population | Exergame platform | Training procedure | Key outcome measurements | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agmon et al. (2011)19 America |

To determine the safety and feasibility of exergaming to improve balance in older adults | Pre-post VIII |

Seven community-dwelling older adults with impaired balance, mean age (SD) 84 (5), four women | Nintendo Wii | 3 months (three times a week for 30 minutes) with at least five home visits with individualized instructions |

Balance: BBS Mobility impairment and gait speed: Timed 4-Meter Walk Test Exercise enjoyment: PACES Feasibility and safety: Semi-structural weekly phone calls and written logs, and semi structural interview at post-test |

Improved BBS, Timed 4-Meter Walk Great enjoyment after exergaming Expressed improved balance in daily activity and desire to play with their grandchildren Two games had to be modified to ensure safety, no participants experienced a fall during the intervention |

| 2. Anderson-Hanley et al. (2012)20

America |

To compare the cognitive benefits of cybercycling with traditional stationary cycling | RCT III |

79 community-dwelling older adults EXP: n=38, mean age (SD), 76 (10), 33 women CON: n=41, mean age (SD), 82 (6), 29 women |

Cybercycle |

1st month

EXP and CON three times a week (45 minutes) familiarization with biofeedback stationary biking 2nd Month EXP: Cybercycle, three times a week (45 minutes) CON: Traditional biking + placebo training, three times a week (45 minutes) |

Cognitive assessment: Color Trials 2-1 difference score, Stroop C, Digit Span Backwards Physiologic: iDXA (GE Lunar, Inc.). HUMAC Cybex Dynamometer (CSMI Solutions, Inc.), insulin, glucose Assessment of exercise behavior: ACLS-PAQ, accelerometer, ride behaviors recorded with bike computer Neuroplastic assessment: Fasting morning plasma, BDNF levels |

Improved cognitive performance in executive function and neuroplasticity. EXP 23% relative risk reduction in clinical progression to mild cognitive impairment Effort and fitness no factors behind differential cognitive benefits in EXP |

| 3. Anderson-Hanley et al. (2011)21

America |

To examine the effect of virtual social facilitation and competitiveness on exercise effort in exergaming older adults | Subgroup analyses IV |

14 community-dwelling older adults (eight low competiveness, six high competiveness), age range 60–99, 13 women | Cybercycle | 1 month (2–3 rides a week), cybercycling with virtual competitors |

Competitiveness: Competitiveness Index Exercise effort: 10 second interval by cybercycle sensors |

High competiveness older adults had a higher riding intensity than low competiveness older adults |

| 4. Chuang et al. (2006)22

Asia |

To evaluate the effect of a virtual “country walk” on the number of sessions necessary to reach cardiac rehabilitation goals in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting | RCT III |

20 male outpatients who had bypass surgery EXP: n= 10, mean age (SD) 66 (15) CON: n=10, mean age (SD) 64 (10) |

Cyberwalking | EXP: 3 months (twice a week for 30 minutes) cyberwalking CON: 3 months (twice a week for 30 minutes) training on treadmill |

Cardiorespiratory testing: The Naughton protocol Maximum work rate: Treadmill speeds and grades |

Number of sessions required to reach target heart rate and target VO2 was lower in EXP than CON Maximum workload EXP was higher than CON |

| 5. Maillot et al. (2011)23

Europe |

To assess the potential of exergame training in cognitive benefits for older adults | RCT III |

32 community-dwelling older adults, mean age (SD) 73 (3), 27 women EXP: n=16, mean age (SD) 73 (4) CON: n=16, mean age (SD) 73 (3) |

Nintendo Wii | EXP: 14 weeks (24 times 1 hour) exergaming CON: No training, no contact |

Physical impact of the training: The functional fitness test Executive control tasks, visuospatial tasks, processing-speed task: The cognitive battery |

EXP had a higher game performance, physical function, cognitive measured of executive control and processing speed than CON No differences between EXP and CON on visual spatial measures |

| 6. Rand et al. (2008)24

Asia |

To investigate the potential of using exergaming for the rehabilitation of older adults with disabilities | Pre-post VIII |

Study 1: 34 young adults, mean age (SD) 26 (5), 17 women Study 2: 10 older adults without a disability, mean age (SD) 70 (6), six women Study 3: 12 individuals age range 50–91, seven women |

IREX VR system Sony PlayStation EyeToy |

Study 1: Played the two exergame platforms for 180 seconds in addition to 60 seconds of practice, in total 40 minute 1 time session in a clinic Study 2: Played three exergames on the Sony PlayStation 180 seconds in addition to 60 seconds of practice at home Study 3: Played two exergames on the Sony PlayStation 180 seconds in addition to 60 seconds of practice at home, clinic or hospital |

Sense of presence: PQ Feedback of exergames: SFQ Physical effort: Borg’s Scale of Perceived Exertion Performance: Monitored by scores in each exergame System usability: SUS |

No difference in sense of presence IREX and EyeToy in young adults High enjoyment exergaming in the research population EyeToy seems less suitable for acute stroke patients |

| 7. Rosenberg et al. (2010)25

America |

To assess the feasibility, acceptability, and short-term efficacy and safety of a novel intervention using exergames for SSD | Pre-Post VIII |

19 community-dwelling adults with SSD, mean age (SD) 79 (9), 13 women | Nintendo Wii | 12 weeks (three times a week for 35 minutes) exergaming with guidance Follow up: 12 weeks after intervention |

Mood: QIDS, BAI Health-Related QoL: MOS SF-36 Cognitive functioning: RBANS Rating individual Wii Sports on enjoyment: Likert scale from 1 (least) to 7 (most) Wii adherence: Log of activity for 12 weeks |

Decrease in depressive symptoms Increase in mental related QoL and cognitive function Adherence 84% No major adverse events |

| 8. Saposnik et al. (2010)26

America |

Comparing the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of exergaming in rehabilitation versus recreational therapy (playing cards, bingo, or jenga) | RCT III |

22 stroke patients, mean age (range) 61 (41–83), 14 women EXP: n=11, mean age (range) 67 (46–83) CON: n=11, mean age (range) 55 (41–72) |

Nintendo Wii | EXP: 2 weeks (eight sessions of 60 minutes) exergaming CON: 2 weeks (eight sessions of 60 minutes) recreational therapy Follow-up: 4 weeks after intervention |

Feasibility: Time tolerance and adaption to exergaming (total time receiving intervention) Safety: Proportion of patients experiencing intervention-related adverse events or any serious adverse events during the study period Motor function: WMFT |

No serious adverse events No difference EXP and CON in symptoms No difference in feasibility between EXP and CON EXP had higher motor function than CON |

| 9. Smith et al. (2012)27

Oceania |

To develop and establish characteristics of exergaming in older adults | Pre-post VIII |

Recruited from a pool of 44 community-dwelling older adults, mean age 79 | DDR | One time session in a clinic |

Step responses: USD DDR mat Characteristics of stepping performance: Purpose built software |

Older adults are able to interact with DDR Stepping performance is determined by characteristics of game play such as arrow drift speed and step rate |

| 10. Taylor et al. (2012)28

Oceania |

To quantify EE in older adults playing exergames while standing and seated and to determine whether balance status influences the energy cost associated with exergaming | Pre-post VIII |

19 community-dwelling adults, mean age (SD) 71 (6), 15 women | Nintendo Wii Xbox 360 Kinect |

Played nine exergames, each for 5 minutes, in random order. Bowling and boxing were played both seated and standing |

EE: Indirect calorimeter Balance: Mini-BESTest, ABC scale, TUG |

EE exergaming result in light physical activity No difference EE Nintendo Wii and EE Kinect No difference EE exergaming sitting and standing No difference between EE or activity counts and balance status |

| 11. Wollersheim et al. (2010)29

Oceania |

To investigate the physical and psychological effect of exergaming | Pre-Post, Focus Groups VIII |

11 older women who participated in community planned activity groups, mean age (SD) 74 (9) | Nintendo Wii | 6 weeks (twice a week between 9–130 min each session) exergaming |

Body movements: Accelerometer Psychosocial effects: Focus groups |

EE increased with gameplay No difference in overall EE Results focus groups: Greater sense of physical, social and psychological well-being |

ABC Scale: Activities Specific Balance Confidence Scale; ACLS-PAQ: Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study Physical Activity Questionnaire; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BBS: Berg Balance Scale; BDNF: Brain-derived Neurotrophic Growth Factor; CON: Control group; DDR: Dance Dance Revolution EE: Energy Expenditure; EXP: Experimental group; IREX: Interactive Rehabilitation and Exercise System; Mini-BESTest: Balance Evaluation Systems Test; PACES: Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale; PQ: Presence Questionnaire; QIDS: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms; QoL: Quality of life; RBANS: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; SD: Standard deviation; SFQ: Short Feedback Questionnaire; SSD: Subsyndromal depression; TUG: Timed up and go; USD: Universal Serial Bus; VO2: oxygen uptake; VR: virtual environment.

Table 2.

Articles’ main conclusion.

| Exergame platform | Description of exergame platform | Outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility and safety | Physical activity | Balance | Cognition | Participants’ experiences | ||

| Nintendo Wii | Game computer with a wireless controller which detects movements in three dimensions through Bluetooth | Participants felt comfortable playing after five individualized training sessions19 Certain games were too difficult to play19,29 Adherence: 84–97.50%23,25 Practice resulted in improved performance on exergaming23 No serious adverse events26 Exergaming was feasible for stroke patients26 |

↑ EE29 ↑ Gait speed19 ↑ Physical status, especially cardiorespiratory fitness23 Exergaming resulted in light to moderate intensity range of activity23,28 ↑ Motor function26 No difference in EE exergaming while standing or sitting28 |

↑ Balance19 No relationship between EE or activity and balance status28 |

↑ Cognitive benefit23,25 ↑ Executive function23 ↑ Processing speed23 |

High level of enjoyment19,23 and would like to continue exergaming23 An experience that could be shared with the family, especially with grandchildren19,29 ↑ Mental related Quality of Life25 No increase in symptoms26 and decreased depression symptoms25 ↑ Sense of physical, social and psychological well-being29 |

| Dance Dance Revolution (DDR) | Game computer with a dance mat including four step-sensitive target panels | Older adults were able to interact with the DDR27 Stepping performance was determined by characteristics of game play such as arrow drift speed and step rate27 |

||||

| Xbox 360 Kinect | Game computer with a webcam-style add-on peripheral that enables players to interact without the need to touch a game controller | Exergaming resulted in light physical activity28 | ||||

| Sony PlayStation Eyetoy | Game computer with a USB camera that translates body movements into a controller input | Less suitable for acute stroke patients24 | High enjoyment and sense of presence exergaming24 | |||

| Cybercycling | Enhanced stationary cycling using virtual tours | ↑ EE than stationary cycling20 | ↑ Cognitive benefit, executive function compared to stationary biking20 | Introduction of an on-screen competitor led to an increase in riding intensity for more competitive older adults, compared to less competitive, older adults21 | ||

| Cyberwalking | Enhanced treadmill walking using virtual tours | ↑ Max workload in cyberwalking than treadmill22 ↓ Number of sessions required to reach target heart rate and VO2 when cyberwalking compared to treadmill training22 |

Participants described cyberwalking as feeling immersed in the VR scene22 | |||

EE: energy expenditure; VR: virtual reality; VO2: oxygen uptake.

The methodological quality was evaluated by a classification system, which has previously been used in reviews on new health technology and medical procedures in health care (Table 3).18 In this scoping review the methodological quality of the studies did not determine inclusion or exclusion.

Table 3.

Classification of study designs (18).

| Level | Strength of evidence | Type of study design |

|---|---|---|

| I | Good | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| II | Large-sample randomized controlled trials | |

| III | Good to fair | Small-sample randomized controlled trials |

| IV | Non-randomized controlled prospective trials | |

| V | Non-randomized controlled retrospective trials | |

| VI | Fair | Cohort studies |

| VII | Case-control studies | |

| VIII | Poor | Non-controlled clinical series, descriptive studies |

| IX | Anecdotes or case reports |

Results

A total of 50 articles were found in the databases. Sixteen articles were duplicated in the databases and 26 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Three additional articles were found through a manual search. Finally, a total of 11 articles were included (Figure 1).

Methodological aspects of the studies

One study was published in 2006,22 one in 2008,24 three in 2010,25,26,29, three in 2011,19,21,23, and three studies were published in 2012.20,27,30 Four studies used a randomized design.20,22,23,26 Because of the low number of participants in each randomized study (20–63 participants), the evidence of these studies is good to fair (Table 3). Seven studies used a pre-posttest design without a control group.19,21,24,25,27–29 One study reported a subgroup analysis of a randomized control trial21 and one pre-posttest study reported results from focus group interviews.29 Only two studies used a longer follow-up period; 4 weeks26 and 12 weeks.25

Research populations

The largest study in this review included 63 older adults,20 and the smallest study included seven older adults.19 The majority examined community-dwelling older adults.19,25,28,29 Three studies included patient populations. One study included 32 patients with cardiac disease,22 two studies included stroke patients, one included 12 stroke patients and 10 older adults without a disability24 and one study included 22 stroke patients.26 Nine studies included both men and women. In these studies the majority of the participants were female (between 57 and 93%).19–21,23–27,30 One study included only men (n=20)22 and one only women (n=11).29 The age range in the studies was 50–99 years old.

Safety and feasibility of exergaming

The exergame platforms in the studies seem to be safe and feasible with none of the studies reporting adverse events. After having received instructions and familiarized themselves with the exergames, stroke patients had no problems playing them.26 In a study where a balance board was used (on which the player stands during training), two games had to be modified due to muscle pain or balance problems in order to be safe and feasible. In this study patients had no problems playing the games after five individualized training sessions.19 In one study including older women, there were difficulties playing some of the exergames on the Nintendo Wii, and this study reported that mastery of the exergame seemed to be an important factor when choosing a favorite game to play.29 The Sony PlayStation EyeToy was feasible for older adults and stroke patients. It was less suitable for acute stroke patients due to weak upper extremity, which made it difficult to interact with the exergame platform.24 Older adults were able to interact with the Dance Dance Revolution. A significant relationship was found between stepping performance and stimuli characteristics, but the stepping performance decreased as stimulus speed and step rate were increased.27 The adherence in exergaming was between 84 and 98%.23,25,26

Physical activity in exergaming

Eight studies using different instruments measured outcomes in physical activity (Table 1). Playing the exergames resulted in more EE compared to rest and to sedentary computer gaming.28 No significant difference in EE was found in playing bowling and boxing on the Nintendo Wii while standing up compared to playing these games while seated.28 In addition, no difference in EE was found between the exergame platforms Nintendo Wii and Xbox Kinect.28 Playing the exergames resulted in an EE of light intensity exercise to moderate intensity activity.23,28 No significant correlation was found between EE or activity counts and balance status while bowling or boxing on the Nintendo Wii.23

Adding a virtual competitor in cybercycling increased the exercise effort among the more competitive exercisers.21 Cardiac patients who rehabilitated with cyberwalking had an increased workload and needed fewer sessions to reach their maximum heart rate and oxygen uptake, compared to a control group who had rehabilitation with only a treadmill.22

Balance in exergaming

Three studies included balance as an outcome, using different instruments to measure this concept (Table 1). Participants experienced improved balance in daily activities after exergaming with the Wii Balance Board.19 One study showed that balance was not related to the amount of physical activity.28

Cognition and exergaming

Cognitive change has been examined in three studies, measured by different instruments (Table 1). Participants had improved cognitive function in all of the three studies after exergaming,20,23,25 especially in executive function and processing speed.23 Cybercycling achieved better cognitive function than traditional exercises, using the same effort.20

Experience in exergaming

Five studies included the experiences of participants who had used the exergame platform. The participants enjoyed playing the exergames19,23,24 and liked to continue using them.23 The studies do not report on preference based on age and gender. Participants who played exergames decreased in depressive symptoms (sustained at 12 week follow-up), and increased in Mental related Quality of Life25 and empowerment,29 measured with validated questionnaires (Table 1). They perceived health benefits in terms of greater ease of movements and psychosocial well-being.29 Within their family, the exergames allowed them to share experiences, which made them feel more connected with their family members, especially their grandchildren.19,29

Discussion

Although this research field is still small and developing, we found that using exergame platforms might be a potentially effective alternative to facilitate rehabilitation therapy after illness and are suitable for use in older adults.

The studies showed that exergaming was safe and feasible, and could increase physical activity in elderly patients suffering from stroke and cardiac disease. The physical activity level increased while playing exergames, from light intensity exercise to moderate intensity activity. In four studies, exergaming resulted in positive outcomes in relation to balance and cognitive performance.20,23,25,30 In four studies, participants reported enjoyment in being active and one study resulted in a decrease of depressive symptoms.19,23,24,29 An important aspect of introducing exergaming to older adults is that a proper familiarization period is included and guidance is provided.

It will still be a challenge to find the most suitable exergame for a certain patient group. Although all games were found to be effective, some games were more strenuous than others and this might be important to consider when implementing or testing a certain exergame in a specific population. The commercial exergame platforms have the advantages that they are relatively cheap and health care providers have reported that the use of a commercial exergame platform (Nintendo Wii) provided purposeful and meaningful opportunities to promote well-being for older and disabled clients within a care and disability service for the elderly.31

This review is a first step to investigate the possibility of using an exergame platform to help patients with HF to adopt a more physically active lifestyle. The results of this review suggest that exergames increase physical activity in elderly individuals, stroke patients and cardiac patients, and could therefore be feasible and safe for patients with HF. However, further testing is needed. This review has some limitations, mainly the small sample sizes in the studies included in the review and the fact that most studies did not include a control group.

The findings of this review may have implications for both the current policy on delivery intervention programs that aim to increase physical activity, as well as the direction of future research. Further research, with a higher level of methodological quality and that examines the relative efficacy and costs of intervention programs aimed to enhance daily activity in non-health care settings, such as home settings, is needed. Also, a longer follow up period is needed to examine the long-term effects of these promising exergame platforms. Therefore, a RCT-study is planned to assess the influence of exergaming on exercise capacity in patients with heart failure (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT01785121).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Implications for Practice:

- Exergames increases physical activity in elderly, stroke patients and cardiac patients

- Exergames could be feasible and safe for patients with heart failure

- Further research is needed to assess the influence of exergaming in patients with heart failure

References

- 1. Piepoli MF, Conraads V, Corrà U, et al. Exercise training in heart failure: From theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2012; 14: 803–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keteyian SJ, Fleg JL, Brawner CA, Piña IL. Role and benefits of exercise in the management of patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2010; 15: 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams V, Linke A, Gielen S, Erbs S, et al. Modulation of Murf-1 and MAFbx expression in the myocardium by physical exercise training. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008; 15: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rees K, Taylor RS, Singh S, et al. Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004: CD003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corvera-Tindel T, Doering LV, Woo MA, et al. Effects of a home walking exercise program on functional status and symptoms in heart failure. Am Heart J 2004; 147: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jolly K, Lip GY, Taylor RS, et al. The Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation study (BRUM): A randomised controlled trial comparing home-based with centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Heart 2009; 95: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dracup K, Evangelista LS, Hamilton MA, et al. Effects of a home-based exercise program on clinical outcomes in heart failure. Am Heart J 2007; 154: 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piepoli MF, Davos C, Francis DP, et al. Exercise training meta-analysis of trials in patients with chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH). BMJ 2004; 328: 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flynn KE, Piña IL, Whellan DJ, et al. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 301: 1451–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van der Wal MH, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Veeger NJ, et al. Compliance with non-pharmacological recommendations and outcome in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 1486–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor-Piliae RE, Silva E, Sheremeta SP. Tai Chi as an adjunct physical activity for adults aged 45 years and older enrolled in phase III cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012; 11: 34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conraads VM, Deaton C, Piotrowicz E, et al. Adherence of heart failure patients to exercise: Barriers and possible solutions: A position statement of the Study Group on Exercise Training in Heart Failure of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2012; 14: 451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kharrazi H, Shirong A, Gharghabi F, et al. A scoping review of health game research: Past, present, and future. Games Health J 2012; 1: 153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peng W, Lin JH, Crouse J. Is playing exergames really exercising? A meta-analysis of energy expenditure in active video games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011; 14: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Plow MA, McDaniel C, Linder S, et al. A scoping review of exergaming for adults with systemic disabling conditions. J Bioengineer & Biomedical Sci 2011; S1: 002. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jovell AJ, Navarro-Rubio MD. [Evaluation of scientific evidence]. Med Clin (Barc) 1995; 105: 740–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agmon M, Perry CK, Phelan E, et al. A pilot study of Wii Fit exergames to improve balance in older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2011; 34: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, Brickman AM, et al. Exergaming and older adult cognition: A cluster randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42: 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson-Hanley C, Snyder AL, Nimon JP, et al. Social facilitation in virtual reality-enhanced exercise: Competitiveness moderates exercise effort of older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2011; 6: 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chuang TY, Sung WH, Chang HA, et al. Effect of a virtual reality-enhanced exercise protocol after coronary artery bypass grafting. Phys Ther 2006; 86: 1369–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maillot P, Perrot A, Hartley A. Effects of interactive physical-activity video-game training on physical and cognitive function in older adults. Psychol Aging 2011; 27: 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rand D, Kizony R, Weiss PT. The Sony PlayStation II EyeToy: Low-cost virtual reality for use in rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther 2008; 32: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenberg D, Depp CA, Vahia IV, et al. Exergames for subsyndromal depression in older adults: A pilot study of a novel intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18: 221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saposnik G, Teasell R, Mamdani M, et al. Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming technology in stroke rehabilitation: A pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Stroke 2010; 41: 1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith ST, Sherrington C, Studenski S, et al. A novel Dance Dance Revolution (DDR) system for in-home training of stepping ability: Basic parameters of system use by older adults. Br J Sports Med 2011; 45: 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor LM, Maddison R, Pfaeffli LA, et al. Activity and energy expenditure in older people playing active video games. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 2281–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wollersheim D, Merkes M, Shields N, et al. Physical and psychosocial effects of Wii video game use among older women. iJETS 2010; 8: 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taylor LM, Maddison R, Pfaeffli LA, et al. Activity and energy expenditure in older people playing active video games. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 2281–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins HC, Horton JK, Hodgkinson BC, et al. Lessons learned: Staff perceptions of the Nintendo Wii as a health promotion tool within an aged-care and disability service. Health Promot J Austr 2010; 21: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]