Abstract

This meta-analysis synthesized 34 HIV prevention interventions (from 27 studies) that were evaluated in Latin American and Caribbean nations. These studies were obtained through systematic searches of English, Spanish, and Portuguese-language databases available as of January 2009. Overall, interventions significantly increased knowledge (d = 0.51) and condom use (d = 0.28) but the effects varied widely. Interventions produced more condom use when they focused on high-risk individuals, distributed condoms, and explicitly addressed socio-cultural components. The best-fitting models utilized factors related to geography, especially indices of a nations’ human development index (HDI) and income inequality (i.e., Gini index). Interventions that provided at least three hours of content succeeded better when HDI and income inequality were lower, suggesting that intensive HIV prevention activities succeed best where the need is greatest. Implications for HIV intervention development in Latin America and the Caribbean are discussed.

Keywords: Latin America, Caribbean countries, behavioral intervention, HIV prevention, poverty, condom use

Introduction

An estimated 1.7 million people were HIV-positive across Latin American and Caribbean nations (LACNs) in 2007, of which 140,000 were newly infected.1 Although the AIDS epidemic is much more severe in LACNs than in Europe and North America, only recently has a critical mass of HIV prevention intervention work appeared. Prior reviews have noted that these trials’ results varied widely.2,3 A systematic review that identifies the strategies and study features that are responsible for these variations offers the hope of informing more effective interventions for slowing the epidemic.

One likely facilitator of the spread of HIV in LACNs are rigid and restrictive social-cultural norms regarding sexuality and contraception, and conservative gender roles that proscribe very specific behaviors for both men and women. Whereas there is great cultural diversity across LACNs, extensive research has documented three main cultural beliefs that relate to HIV risk and that are predominant in most LACNs: (a) machismo, or “male pride,” is the belief that men should be dominant, have multiple sex partners,4 and engage in unprotected sex,5–9 (b) simpatía, which endorses a traditional female role emphasizing sexual submission,10–14 and (c) familismo, associated with traditional family values which conflict with less socially acceptable forms of sexual expression, such as condom use and homosexuality.15–20 These three dimensions help enforce taboos with respect to sexual communication, untraditional sexual behaviors, contraception, and HIV/AIDS and other STDs, thereby contributing to the pervasive stigmatization of high-risk groups. Additionally, as these social-cultural beliefs are internalized and stable in nature, it is more difficult for interventionists to address the root behaviors related to HIV transmission, further hindering the implementation of efficacious sexual health interventions.2 Previous HIV prevention research with Hispanic populations in non-LACNs has demonstrated that interventions directly addressing these social-cultural beliefs and barriers (e.g., changing popular cultural norms15) have had greater success at eliciting risk reduction.17,21 Moreover, intervention work with adolescents has been shown to be more effective when cultural beliefs are addressed, both in LACNs and with Latinos living in the U.S.22,23

In addition to cultural elements, extreme poverty and lack of basic education persist through the LACNs and serve as a conduit for higher rates of risky behaviors and increased HIV transmission. Income and other country development indexes, which are the best available approximations of the socioeconomic environment by country, often correlate with the availability of resources24 and HIV prevalence.25 Haiti, for example, has the highest prevalence of HIV in LACNs, as well as some of the lowest scores on the Human Development Index (HDI) and the Gender-related Development Index (GDI), which gauge development based on indexes of longevity, GDP per capita, and level of education.26 Income equality (i.e., low Gini index27) is another development indicator, which suggests that greater income equality is related to higher levels of development. Because relatively intense interventions provide much needed resources, they should succeed better in LACNs that are relatively low on HDI, GDI, and exhibit greater income equality. In other words, prevention efforts are likely to succeed best where there is a widespread, common experience of shorter life expectancies, greater poverty, and less education than in more developed nations. Similarly, interventions that take an ecological approach, which considers all micro-, meso-, and macro-level risk determinants, should offer greater prevention outcomes.28

Whereas previous synthesis research has recognized the potential importance of broad structural factors on the efficacy of HIV interventions and considered them in a descriptive capacity,17,21 none to date has evaluated both individual and structural features as moderators of intervention efficacy and no prior review of HIV interventions in LACNs has taken a quantitative approach.2,3 Whereas there have been meta-analyses of interventions targeting Hispanics,17,21 these reviews focused on samples from the United States and omitting almost all studies from LACNs. The current work is the first to examine the efficacy of HIV/AIDS interventions specifically targeting people living in their native LACNs.

Methods

Studies were selected from (a) electronic databases {i.e., MEDLINE, PsycINFO, AIDSearch, the Spanish database CSIC, and the Brazilian database SciELO; Boolean search: [HIV OR AIDS OR (human immu* virus) OR (acquired immu* syndrome) OR STD OR STI OR (sexually transmitted disease*) OR (sexually transmitted infection) OR (names of specific diseases) AND (interven* or prevent*) AND (sex* OR condom* OR intercourse) AND (names of developing LACNs)]}; searches were also conducted in Spanish and Portuguese using the appropriate translations, (b) the NIH database of grant awardees, (c) conference proceedings (e.g., the International AIDS Conference), and (d) the reference lists of each paper we obtained.

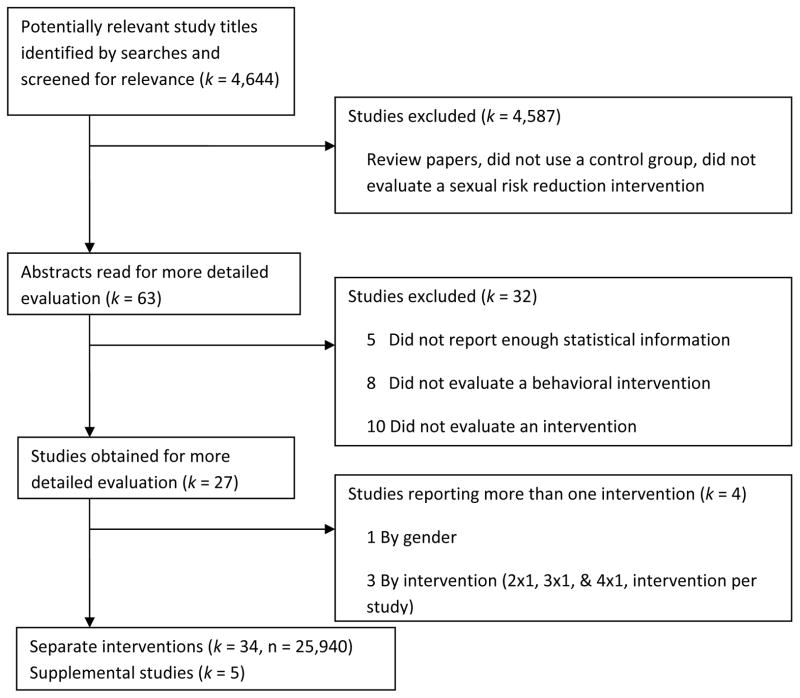

Studies conducted in LACNs that were available by January 2009 were included in the database if they (a) examined risk-reduction interventions focused on increasing HIV-related knowledge or condom use with some face-to-face interaction (including interactions where outreach workers provided condoms or educational material), (b) either a randomized controlled trial design or evaluated success relative to baseline, (c) measured a sexual risk reduction marker (i.e., condom use, number of partners, HIV/STD prevalence or HIV knowledge), and (d) presented information needed for effect size (ES) calculation. Excluded were studies that (a) focused on perinatal transmission contexts or behaviors, (b) did not emphasize HIV/AIDS-preventive content, and (c) did not report statistical information needed to calculate the ESs. In 7 studies, information was insufficient to calculate effect sizes; queries to these authors permitted retaining 2 (29%) of these studies. Use of these criteria yielded 27 independent studies including 5 studies containing supplemental information (e.g., demographic characteristics, intervention details), that provided 34 separate interventions and included 25,940 participants. Each intervention was treated as an individual study (see flow chart).

Two trained raters independently coded each study for their methodology, sample, and intervention characteristics (see Table I). Across the study- and intervention-level categorical dimensions, coders agreed on the majority of judgments (κ = 0.95) and for the continuous variable the mean for Spearman-Brown correlation coefficient was 0.97. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Additionally, the individual studies were coded for HDI, GDI,29–38 and Gini index27 values corresponding to the country and year of data collection (or if unavailable, values for two years before publication were used). In several instances, values were not available for the exact year of data collection, in which case, values from the closest available year were used. HDI values were also clustered according to the UN’s categorization of High HDI countries (with values from 0.800 to 1.000), Medium HDI countries (with values from 0.500 to 0.799), and Low HDI countries (with values from 0.000 to 0.499).

Table I.

Descriptive Features of 34 interventions (reported in 27 Studies) in Sample.

| Report characteristics (k = 27)

| |

| Year of publication (r = 1) | |

| M | 1999 |

| Mdn | 1999 |

| SD | 4.51 |

| Year of data collection (r = 0.85) | |

| M | 1996 |

| Mdn | 1996 |

| SD | 4.65 |

| Region (κ = 1) | |

| South or Central America | 14 |

| Mexico or Caribbean | 13 |

| Language of Report (κ = 1) | |

| English | 23 |

| Spanish | 4 |

| Geographical context (κ = 0.95) | |

| Urban | 26 |

| Rural | 1 |

| Human Development Index (κ = 1) | |

| High | 8 |

| Medium | 15 |

| Low | 4 |

| Gini Coefficient (κ = 1) | |

| High (> = 57) | 8 |

| Medium | 11 |

| Low (<= 50) | 8 |

| Gender-related Development index (κ = 0.96) | |

| High (> = 79) | 7 |

| Medium | 13 |

| Low (<= 65) | 7 |

| Design (κ = 1) | |

| Within-subjects | 6 |

| Between-subjects | 3 |

| Mixed-subjects | 18 |

|

| |

| Intervention characteristics (k = 34) | |

|

| |

| Days between pre- and post-test | |

| M | 184.35 |

| Mdn | 150 |

| SD | 219.74 |

| Risk level (κ = 0.95) | |

| Relatively low | 20 |

| Relatively high | 13 |

| Implementation was (κ = 0.80) | |

| Groups | 20 |

| Individual | 4 |

| Mixed | 5 |

| Couples | 5 |

| Intervention time (κ = 0.95) | |

| Less than 3 hours | 9 |

| 3 hours or more | 25 |

| Type of intervention (κ = 0.84) | |

| Behavioral change | 34 |

| Structural/environmental | 8 |

| School-based HIV education | 15 |

| Harm reduction for IDUs | 4 |

| Community-wide risk | 15 |

| Condom promotion | 34 |

| Intervention included (κ = 0.9) | |

| Individualized component | 10 |

| Counseling and Testing | 10 |

| Control participants (irrelevant content) | 16 |

| HIV education | 30 |

| Biological only (HIV/sexual health basics) | 0 |

| Condom negotiation skills | 24 |

| Partners included | 6 |

| Behavioral (skills training) only | 14 |

| Biological/Behavioral | 15 |

| Social-Cultural barriers discussed | 7 |

| Biological/Social-Cultural | 10 |

| Condom use education and prevention | 34 |

| Distributing Condoms | 16 |

| Media (e.g., pamphlets, posters) | 10 |

| Main goal of intervention (κ = 0.95) | |

| Abstinence | 3 |

| Condom use 100% | 34 |

| Reduced number of partners | 6 |

| Lower incidence of STI | 23 |

|

| |

| Participant characteristics (k = 34) | |

|

| |

| N at posttest (r = 0.84) | |

| Total | 25,940 |

| M | 762.94 |

| Mdn | 264 |

| SD | 1162.9 |

| % female (r = 1) | |

| M | 47.47 |

| Mdn | 50 |

| SD | 33.82 |

| k | 34 |

| % HIV prevalence (r = 1) | |

| M | 33.44 |

| Mdn | 30 |

| SD | 32.60 |

| k | 10 |

| Average age (r = 1) | |

| M | 24.012 |

| Mdn | 24 |

| SD | 9.013 |

| k | 34 |

Note. Characteristics describing “Type of Intervention” and “Intervention Included” are not mutually exclusive.

We calculated individual ESs for the two outcomes that were present in sufficient numbers to meta-analyze: (a) condom use, including reports of condom use with casual and steady partners (averaged when both were present) and (b) knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention methods. We focus on those two main outcomes due to the small number of studies that report other outcomes (i.e., 2 reporting results on sexual debut,59,69 1 on number of partners,58 3 on other sexual frequencies,51,61,74 and 2 on biological outcomes52,74). ESs were calculated based on the measures provided at the first available follow-up after the intervention. When the outcomes of interest were continuous, we calculated ESs in the appropriate form of the standardized mean difference (d)39,40 for each design; for cases in which both the independent and the dependent variable were categorical, odds ratios were used and then transformed to d using the Cox transformation.41 The signs of ESs were set so that positive values indicated risk reduction (i.e., increased condom use or knowledge). Consistent with meta-analytic convention, each intervention was treated as an individual study during analysis,42,43 including cases when an article provided information regarding multiple interventions or when statistical summaries grouped results separately for gender, location, or targeted group.

For each outcome, analyses followed random- and fixed-effects assumptions to estimate means and homogeneity (Q and I2) of the ESs (ds).44 Sensitivity analyses examined whether use of within-subjects designs impacted the main results. Coded features were analyzed as possible effect modifiers. A large enough sample of ESs permitted moderator testing for condom use, but not for knowledge. Study dimensions that related significantly to ES variability were entered into a series of meta-regression models controlling for intercorrelations among the maintained study dimensions. These models permit a determination of the extent to which variation may be uniquely attributed to surviving study dimensions (Bonferroni p ≤ 0.01). A model with simultaneous inclusion of all predictors was not possible due to the size of the literature. Instead, the single predictor with the largest relation to ds was paired sequentially with other significant univariate predictors; dimensions that retained significance and exhibited stable coefficients were retained. To determine the robustness of this model, we again evaluated the surviving study dimensions in the face of a random-effects (RE) constant. Such mixed effects models are known to have more conservative statistical power than fixed-effects moderator models in the face of heterogeneity.45

Results

The analyses included 34 interventions from 27 studies.46–77 The studies in the sample were published between 1991 and 2008; eight were implemented in Mexico,46–47,51–56 five in Brazil,57–61 two in Nicaragua,62,63 two in Colombia,64,65 two in Puerto Rico,66,68 and one each from Ecuador,69 Peru,70 the Dominican Republic,71 Argentina,72 Belize,73 Haiti,74 Honduras,75 and Bolivia.76 Thus, fourteen studies (52%) were conducted in Central or South America and thirteen studies (48%) were implemented in Mexico or the Caribbean. The mean HDI of these countries for the year of data collection (or if not reported, year of publication) was 0.69 (SD = 0.15) with a range from 0.34 to 0.88 (in comparison, the HDI for the U.S. is 0.95 and for Canada is 0.96); the mean GDI was 0.70 (SD = 0.11) with a range from 0.33 to 0.81, with all values lower than commonly seen in more developed nations (e.g., 0.99 for the U.S. and 0.96 for Canada). The mean Gini index value was 52.8 (SD = 4.41) with a range from 43.87 to 59.32, which is fairly high compared to developed nations (e.g., 24.7 for Denmark, 40.8 for the U.S., and 74.3 for Namibia).

The majority of the interventions (25 [68%]) devoted more than three hours to the intervention and nine (26%) devoted three hours or less. All of the interventions focused on behavioral change and included condom promotion, but only sixteen studies (47%) included condom distribution. All interventions were delivered in the native language of the country. The fifteen (44%) school-based interventions with adolescents accounted for the bulk of studies that omitted condom distribution, as well as discussion of social-cultural barriers to condom use. See Table I and Table II for further information on the main descriptive features of the included studies.

Table II.

Descriptive Features of 27 Studies in Sample

| Study | Sample | Location | Intervention(s) Focus | Time to 1st Assessment Post-Baseline | Intervention duration | Key Outcomes Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antunes, Stall, Paiva et al. (1997)57 | 304 young adult, ages 18–25, from 4 demographically similar night schools | Sao Paulo, Brazil | School-based intervention in small groups, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, sociocultural component, condom use promotion | 183 days | 4 sessions of 3 h each | Condom use |

| Barros, Barreto, Perez et al. (2001)69 | 639 adolescents, ages 12–15 | Santo Domingo de los Colorados, Ecuador | School-based intervention HIV/AIDS education, behavioral skills, biosociocultural component condom use promotion, abstinence | 240 days | 12 h in separate sessions | Knowledge |

| Bronfman, Leyra & Negroni (2002)46 | 301 truck drivers | Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico | Community-based intervention, media-assisted STD/HIV/AIDS education, condom use promotion, small groups with an individual component | 150 days | 90 days | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Cáceres, Rosasco, Mandel et al. (1994)70 | 1213 adolescents from 14 schools, ages 11–21 | Lima, Peru | School-based intervention, STD/HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, biosociocultural component, condom use promotion | 30 days | 7 weekly 2 h sessions | Knowledge |

| Calderón, López, & Bonilla (1991)64 | 324 young adults, ages 18–25 | Cali, Colombia | Behavioral intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, sociocultural component, condom use promotion | 180 days | 180 days | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Colón, Robles, Freeman et al. (1993)66,67 | 1173 IDUs, age mean 32.5 | San Juan, Puerto Rico | Community-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education, counseling, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom use promotion, participants as part of the treatment | 210 days | 4 sessions of 45 minutes, one for counseling, 3 group session | Condom use |

| Deschamps, William, Hafner et al. (1996)74 | Discordant heterosexual couples, age mean 33.5 | Port au Prince, Haiti | Counseling-testing intervention, behavioral and negotiation skills, HIV/AIDS education, condom use promotion, condom distribution, partners in the intervention | 180 days | 2 counseling sessions and 2 testing sessions | Condom use |

| Egger, Pauw et al. (2000)62 | 6463 couples CSW and not CSW in 19 motels | Managua, Nicaragua | HIV/AIDS education, STD education, behavioral skills, condoms distribution | Unknown | 24 days | Condom use |

| Ferreira-Pinto & Ramos (1995)56 | 105 IDUs’ partners | Ciudad de Juarez, Mexico | HIV/AIDS education, Behavioral skills, socio-cultural components | Unknown | Unknown | Condom use |

| Fox, Bailey, Clarke-Martinez et al. (1993)75 | 134 FSWs, age mean 28 | Tegucigalpa, Honduras | HIV/AIDS education, behavioral skills in groups and with individual component, condom promotion | 120 days | 1 h weekly session, during 10 weeks | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Garcia-Bernal, Castro, Caamano et al. (1996)65 | 1470 adults | Bogota, Colombia | HIV/AIDS education, behavioral skills, condom promotion and condoms distribution | Unknown | Unknown | HIV prevalence, Number of sex acts, Number of unprotected sex occasions, Sex with FSW |

| Givaudan, Van de Vijver, Poortinga, et al. (2007)47–50 | 1566 adolescents, age mean 15.97 | Toluca, Mexico | School-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, with biosociocultural component, condom promotion | 180 days | 2 h session per week during 15 weeks | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Hearst, Lacerda, Gravato et al. (1999)58 | 226 male port workers, ages 12–22 | Santos, Brazil | Worksite-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education using media elements, counseling and lectures, behavioral skills, condom promotion and condom distribution | 365 days | 365 days | Condom use |

| Iurcovich, Lourie, & Brown (1998)72 | 405 adolescents, ages 12–22 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | School-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion | Unknown | 3 sessions of 30 minutes each | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Kinsler, Sneed, Morisky et al. (2004)73 | 150 adolescents from 6 schools, ages 13–17 | Belize City, Belize | School-based intervention, peer-led education, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, sociocultural component, condom promotion | 90 days | 7 weekly sessions | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Levine, Revollo, Kaune et al. (1998)76,77 | 508 FCSW who work at brothels and attend to a public STD clinic, mean age 24 | La Paz, Bolivia | Worksite-based intervention with testing and counseling, HIV/AIDS/STD education through groups and small media, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion and distribution | 1095 days | 1095 days | Condom use |

| Magnani, Gaffikin, et al. (2001)59 | 3520 adolescents, ages 11–19 | Bahia, Brazil | School- and health-clinic-based intervention, HIV/AIDS/Reproductive-health education, biobehavioral and sociocultural components, condom promotion | 730 | 40 weeks (1 or 2 hours per week) | Condom use |

| Martinez-Donate, Hovell et al. (2004)51 | 320 adolescents, mean age 17.6 | Tijuana, Mexico | School-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, sociocultural and biobehavioral components, condom promotion and distribution | 90 days | 3 h | Condom use |

| McBride, Inciardi, Surratt et al. (1998)60 | 617 IDUs, mean age 29 | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | HIV/AIDS education through small media, behavioral and negotiation skills, testing and counseling, needle-cleaning promotion, condom promotion and distribution | 180 days | 90 days 2 session of 1 h and half each. | Condom use |

| Patterson, Semple, Fraga, Bucardo et al. (2005)53 | 82 FCSW, ages 19–49 | Tijuana, Mexico | Counseling-testing intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion and distribution | Unknown | 1 session of 30 minutes | Knowledge |

| Patterson, Mausback, Lozada et al. (2008)52 | 924 FCSW, mean age 33.5 | Tijuana, Mexico | Counseling-testin intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and sociocultural components, negotiation skills | 365 days | 1 session of 35 minutes | Condom use |

| Pauw, Ferrie, Rivera et al. (1996)63 | 2271 residents, ages 15–45 | Managua, Nicaragua | Household-based health education intervention, small groups and media components, behavioral skills, condom promotion and distribution | 365 days | 6 months with 1 session of 25 minutes session | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Pick de Weiss, Andrade-Palos et al. (1994)54 | 1632 adolescents, ages 15–19, mean age 33.1 | Mexico City, Mexico | School-based intervention, HIV/AIDS and Reproductive-Health education, behavioral and negotiation skills, biosociocultural components, condom promotion | 180 days | 24 hours | Condom use |

| Robles, Marrero, Matos et al. (1998)68 | 1004 drug users, ages | San Juan, Puerto Rico | Counseling intervention, HIV/AIDS education, needle-cleaning promotion, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion and distribution | 180 days | 8 sessions of 45 minutes | Condom use |

| Sampaio, Brites, Stall et al. (2002)61 | 227 MSM, mean age 29 | Salvador, Brazil | HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion | 90 days | One session lastin 1–4 hours | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Walker, Gutierrez, Torres et al. (2006)55 | 9372 adolescents, ages 16–17 | Rural setting in Morelos, Mexico | School-based intervention, HIV/AIDS education, behavioral and negotiation skills, condom promotion | 120 days | 32 hours over 15 weeks | Condom use, Knowledge |

| Welsh, Puello, Meade et al. (2001)71 | 541 FCSW, mean age 28 | La Romana & San Pedro, Dominican Republic | Peer-education based HIV/AIDS intervention, behavioral skills, condom promotion | 120 days | 120 days | Condom use |

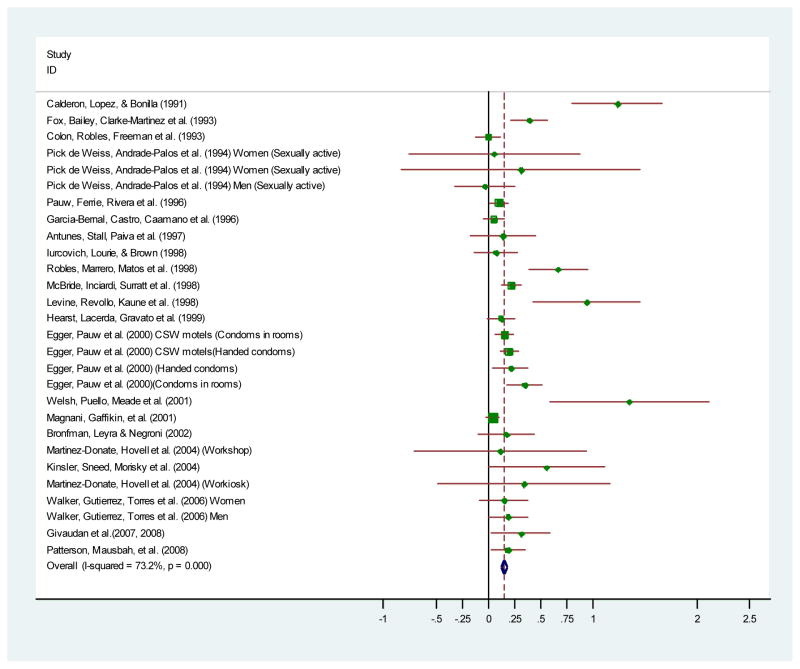

Twenty-eight of the interventions included condom use as an outcome measure; thirteen evaluated knowledge about HIV/AIDS transmission and prevention methods; and nine included both outcomes. One study’s condom use d was a statistical outlier (d = 1.89); it used a within-subjects design, was conducted in Haiti, and had less than three hours of intervention content.74 This intervention was conducted in the country with the lowest HDI, with HIV seropositives and their non-infected partners, and employed counseling and condom distribution. Hence, the large ES is likely due to the intervention including several characteristics most associated with better intervention success. Perhaps the intervention success in this study is also related to differences in culture and circumstance, as Haiti has the weakest Hispanic ties and is the only Francophone country in our sample. Given that the ES was so much greater than the other studies’ results, this study was excluded from further analyses. On average, interventions increased condom use and knowledge about HIV/AIDS transmission and prevention methods. Although the interventions’ effects were overall medium to large in size, the magnitude of change was greatest for knowledge (d = 0.51, d = 0.51, under fixed- and random-effects models, respectively) as compared to condom use (d = 0.15, d = 0.28, under fixed- and random-effects models, respectively). The overall patterns of results did not depend on the use of fixed- or random-effects assumptions. Study outcomes were highly variable (I2 for knowledge = 98.7; I2 for condom use = 73.0); Figure 2 illustrates the variability of the condom use outcomes and reveals that no intervention had significant negative values. Publication bias was examined using trim and fill technique, Begg’s test and Egger’s test and all indicated no significant bias.78–80

Figure 2.

Condom use outcome effect sizes in chronological order.

Sufficient numbers of studies were available to examine effect modifiers only for the averaged condom use ES index. As Table III shows, interventions succeeded better at increasing condom use when they (a) focused on individuals or couples; (b) were conducted in non-school settings; (c) when members of groups at higher risk for HIV infection (community sex workers [CSW], CSW clients, or injection drug users [IDU]) were targeted; (d) when measures were taken sooner after the intervention; (e) distributed condoms, (f) focused on behavior change, and (g) focused on social-cultural components (i.e., discussions about stigma, homophobia, spiritual and ethical issues, gender bias, and gender norms). Some moderators showed high collinearity (rs > 0.62) that, when coupled with the relatively small numbers of studies, did not permit stable tests of these variables in the same model. For example, school-based interventions tended not to distribute condoms and never targeted IDUs or CSWs. In contrast, if an intervention was community-wide, it usually focused on groups at higher risk for HIV infection and incorporated condom distribution. Other moderators listed in Table I were non-significant (e.g., study design, participant characteristics).

Table III.

Efficacy of 34 HIV Interventions at Improving Condom Use as a Function of Sample and Study Characteristics.

| Features of studies | d+ia | 95% CI for d+i | β Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | |||

| Implementation | 0.40* | ||

| Small groups (k = 16) | 0.097 | 0.056, 0.14 | |

| Individual (k = 3) | 0.27 | 0.18, 0.36 | |

| Mixed (individual & groups, k = 5) | 0.14 | 0.065, 0.21 | |

| Couples (k = 3) | 0.20 | 0.15, 0.26 | |

| Risk group | 0.27* | ||

| Relatively low (k = 19) | 0.11 | 0.078, 0.15 | |

| Relatively high (CSW, clients or IDUs, k = 10) | 0.20 | 0.15, 0.24 | |

| Interval in days between pre- and post-test (k = 21) | −0.35** | ||

| 30 | 0.23 | 0.17, 0.30 | |

| 1095 | −0.040 | −0.15, 0.071 | |

| Type of Intervention | |||

| School-based | −0.33** | ||

| No (k = 15) | 0.19 | 0.15, 0.22 | |

| Yes (k = 13) | 0.088 | 0.042, 0.13 | |

| Components within Interventions | |||

| Condom distribution | 0.30* | ||

| No (k = 15) | 0.089 | 0.041, 0.14 | |

| Yes (k = 13) | 0.18 | 0.15, 0.22 | |

| Behavioral components | 0.28* | ||

| No (k = 15) | 0.092 | 0.044, 0.14 | |

| Yes (k = 13) | 0.18 | 0.14, 0.21 | |

| Health and behavioral components | −0.31* | ||

| No (k = 16) | 0.18 | 0.14, 0.21 | |

| Yes (k = 11) | 0.079 | 0.026, 0.13 | |

| Social-cultural components | 0.32* | ||

| No (k = 25) | 0.14 | 0.11, 0.17 | |

| Yes (k = 4) | 0.53 | 0.29, 0.76 | |

| Bio/Social-cultural components | −0.31* | ||

| No (k = 19) | 0.17 | 0.14, 0.21 | |

| Yes (k = 8) | 0.063 | 0.0019, 0.12 | |

Note. Weighted mean effect sizes (d+is) are positive for improvements in the outcome studied and negative for impairments. Each model considers each meta-analysis feature independently rather than simultaneous with the other meta-analysis features.

Displayed values are observations at representative values observed for the study dimension.

Values in this column are standardized regression coefficients. For categorical variables, the beta value was derived by taking the square root of the quotient of QModel divided by QTotal (which results in R2). d+i = Weighted mean effect size. k = Number of studies.

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01

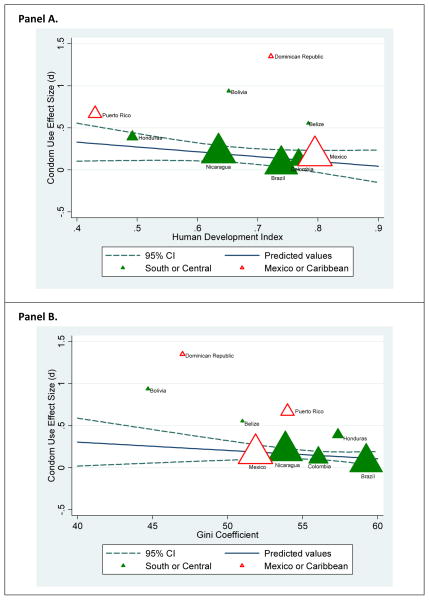

Although HDI, GDI and Gini values did not relate to the efficacy of the trials overall, they did relate significantly to the magnitude of ESs for interventions that were relatively intense, with three or more hours of intervention content (see Table IV). A combined model excluded GDI from these analyses because of high collinearity with HDI (r = 0.92), but added geographical region. Together these three factors explained 54% of the variance in ESs, but left more variation than would be expected by sampling error alone, I2(18) = 51 (95% CI = 18.76, 70.21). Figure 3 shows that for these more intensive interventions, greater efficacy resulted in nations with less development (lower HDI and GDI; refer to Panel A: HDI and condom use), less inequality among citizens (Gini) (refer to Panel B: Gini and condom use), and for those that were evaluated in regions with greatest proximity to the U.S. (i.e., Mexico or Caribbean nations). Moreover, no moderator dimensions listed in the preceding paragraphs remained significant when entered in a model simultaneously with these three dimensions. Finally, a mixed-effects model incorporating a random-effects constant confirmed the same patterns as the purely fixed-effects model.

Table IV.

Condom Use Effect Sizes as a Function of Study Characteristics, for Studies with at least 3 Hours of Intervention Content.*

| Study dimension and level | Adjusted d+ (95% CI)‡ | Standardized regression coefficient (β) |

|---|---|---|

| HDI | −0.53 (p < 0.001) | |

| Low (0.43)† | 0.55 (0.41, 0.69) | |

| High (0.88) | 0.085 (−0.0073, 0.18) | |

| Gini | −0.31 (p < 0.05) | |

| Low (44)† | 0.40 (0.24, 0.56) | |

| High (59) | 0.12 (0.029, 0.23) | |

| Region | 0.31 (p < 0.05) | |

| South or Central America | 0.17 (0.097, 0.23) | |

| Mexico or Caribbean | 0.32 (0.22, 0.42) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; d+, weighted mean effect size; HDI, Human Development Index.

Note. Condom use ESs for 21 studies with more than 3 hours of intervention were modeled as the dependent variable in a weighted least-squares multiple regression, with the two study dimensions simultaneously entered as independent variables. Positive ESs imply greater risk reduction for the intervention group relative to the comparison group. The regression equation was 0.2435 − 1.044(HDI) − 0.0178 (Gini) + 0.0770(region), where region was contrast-coded with 1 indicating Mexico or Caribbean and −1 South or Central America. The model explains 54.5% of the variance and it explained more variance than expected by chance, I2(18) = 51 (95% CI = 18.76, 70.21). The GDI was also negatively related to the efficacy (β = −0.39, p < 0.001), but it was not included in the model because the high intercorrelation with HDI.

Levels represent the range of observed categories, and d+ is plotted for these levels.

Adjusted (statistically controlling) for the inclusion of the other study dimension.

Figure 3.

Condom use effect sizes for relatively intense HIV prevention interventions (i.e. more than 3 hours of content) as a function of human development index (Panel A) and the Gini coefficient (Panel B). The mean appears for nations with more than one intervention.

Discussion

The results from this meta-analysis support the conclusion that HIV interventions aimed at decreasing sexual risk in LACNs are generally successful, especially when measured in terms of increased HIV-related knowledge and improved condom use; however, the findings also indicate that interventions vary widely with respect to their efficacy. These results not only confirm previous reviewers’ observations that HIV interventions had discrepancies in study findings,81 but also demonstrate that much of this variation can be explained. Moderator models explained a significant amount of the variability in the condom use outcomes, with structural variables playing prominent roles, especially for interventions of longer duration. Specifically, these interventions succeeded better in places where the HDI and Gini values were medium or low at the time the intervention was implemented (Figure 3). This finding may seem counter-intuitive, as one might think that the stresses and demands impoverished conditions place on individuals should impede intervention success. Yet, intervention efforts may be particularly effective in countries with the lowest HDIs (and GDI) expressly because of their poverty, and resulting paucity of education, resources and gender differences. In other words, these results corroborate the notion that individuals living in extreme poverty are receptive to intensive interventions that enhance knowledge, empower individuals, encourage prevention, and expand reproductive choice.

The greater success of interventions in countries with low Gini index values is open to several interpretations. For example, it is possible that the socioeconomic inequality in some Latin American countries is a barrier to intervention success. A second interpretation is that countries with less inequality (resulting from a reduced range of mostly lower incomes) makes the participants more receptive to intervention efforts. Further research should explore the precise nature of this relation between income equality and intervention efficacy. Interventions also succeeded better in Mexican and Carribbean countries, when HDI and Gini values are controlled. This pattern also deserves further exploration, though we speculate that it may be related to the influence of the relatively close U.S. culture. A caveat for the interpretation of our results is that the HDI and Gini indices are indicators of development that are not directly linked to specific structural features which are easily observable at the individual-level. Instead, these indices are suggestive of deficits in related structural factors that either facilitate or hurt prevention efforts. We must also remember that the complex social-cultural diversity of LACNs cannot be easily expressed by a single generalization.82 Future investigations should explore potential mediators of the impact of structural-level variables in LACNs and elsewhere.

The current findings confirm Herbst et al.’s17 speculations that structural factors may relate to intervention efficacy and indeed show that broader structural, not individual, factors carry the weight of the results. This finding has important implications for HIV intervention development and is suggestive of the need for real structural changes in tandem with behavior change for magnified results in HIV prevention. A potential direction for interventionists is to work towards creating self-sustaining HIV prevention enterprises that include components that improve economic stability and opportunity (e.g., microfinance83). At the very least, interventionists should be cognizant of the structural framework within which they conduct interventions and target format and content accordingly.84

Although our results suggested that study-specific dimensions had no impact once structural variables were controlled, these factors may still be important because these results pertain to interventions of all length, not just relatively intensive interventions. Small group interventions were generally less effective than individual or couples-based interventions. Given that school-based interventions tended to have a smaller effect and were often administered in a small group setting, these two moderator results are highly related (r = .86). If the small group setting results can be considered a reflection of the fact that school-based interventions tended to not be as efficacious as other groups, then it becomes important to consider why school-based interventions are less effective. One possible culprit is that, from a developmental perspective, adolescents and young adults tend to be more risk prone, impulsive, and increasingly sexually active.85,86 Thus, increased condom use may be more difficult to achieve as compared to older populations; it is of note that such populations also generally have less access to key resources necessary to safe behavior. Similarly, it is often the case that school-based interventions are limited to the resources and skills that the schools and their teachers have to offer. Teachers in these overcrowded and understaffed schools may lack the requisite technical qualifications to implement an intervention effectively. They may also be uncomfortable discussing sexual topics with their students.70,72 In one intervention conducted in Belize,73 it was noted that schools in rural are as refused even to participate in the intervention, suggesting that discomfort with the sexual nature of the intervention reached the administrative level. Such limitations serve as another barrier to effective intervention implementation by potentially reducing the impact of components found to increase intervention efficacy, such as discussions of social barriers to condom use and distribution. Findings from a relatively recent meta-analysis of HIV prevention studies focused on adolescents (in the United States) indicate that inclusion of these elements increases intervention efficacy without increasing the frequency of sexual encounters.87,88

When we analyzed groups typically characterized as more risky (i.e., IDUs, CSWs, CSW clients) as a single category, we found that interventions targeting these groups were more successful at increasing condom use. Because these groups are at elevated risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV, and because they showed relatively greater positive behavior change, more investment in conducting intervention work with high-risk groups in LACNs seems warranted. Intervention success was also more evident close to the end of the intervention and when condoms were distributed. These two findings support similar results from other research. With length of follow-up, it has consistently been found that the effect of interventions (without booster sessions) tends to decline over time.89–91 Also, a great deal of research conducted with a host of contexts and populations has consistently found that condom provision increases their future use.89,90

Finally, type of intervention content proved to be an important predictor of intervention efficacy. Interventions that focused primarily on behavioral components were found to be more efficacious for those groups. This finding aligns with other research and health behavior theories that contends that behavioral skills training is essential to condom intervention success,89,92 and gives further weight to Albarracín et al.’s21 finding that interventions including condom use skills training and condom distribution with Latin American samples are successful at increasing condom use. Our findings also confirm Albarracín et al.’s21 conclusion of the importance of incorporating culture when intervening with Latino/as and that Latina women seem to respond positively to such interventions. Although only four interventions in this meta-analysis included social-cultural components, they were successful either when targeting females52 and or targeting both genders57,64,73. This success suggests that more interventions should directly deal with social barriers to HIV protective behaviors (e.g., condom use and condom negotiation). That is, in LACNs social-cultural issues such as machismo, simpatía, and familismo must be addressed if condom use interventions are to have the maximum impact.

Several limitations of this research should be noted. First, the synthesis included studies from only a few LACNs. This finding demonstrates how overlooked this region has been in HIV literature to date, and the bulk of the interventions reviewed were conducted in only a handful of those countries. Given the growing HIV epidemic coupled with the unique social-cultural makeup of these countries, it is imperative that this gap be addressed. Of note, our main moderator patterns appeared with those interventions that had relatively intensive content, which excluded three countries for which only brief interventions were available. Another issue is that the same structural factors that related to intervention efficacy may have affected the decision to perform prevention trials or the active components that they delivered. Yet HDI and Gini coefficient index values do not correlate with the numbers of intensive (rs = −0.012 and 0.159, respectively) or less intensive interventions (rs = 0.10 and −0.10) that have to date appeared across all 24 LACNs. More research in these and other countries would be helpful to provide greater evidence about the role that economic and cultural factors relate to HIV prevention efficacy. Additionally, given the gendered nature of the social-cultural barriers to HIV prevention experienced in LACNs, we suspect that gender may play more of a role in intervention efficacy than the current results suggest. In this regard, it is worth noting the research to date in LACNs has isolated samples of females primarily in school-based settings, which may not be representative of the factors at work in the broader context and may limit efficacy.

Finally, although MSM and IDUs constitute growing risk groups in LACNs,93 few of the interventions included in this meta-analysis targeted these groups, making it difficult to draw conclusions about how to tailor sexual risk reduction interventions for these groups. The lack of intervention work with those at highest risk for HIV infection is may be due to the social stigmatization and marginalization of these individuals, again suggesting the need for interventions in LACNs to address gender norms and cultural taboos regarding sexuality. The lack of research on these groups may also be attributed to relatively low economic development, which inhibits the development of interventions.

Conclusion

The current analyses outlined herein suggest that greater investment in scientifically evaluated HIV interventions in LACNs is greatly needed. During our investigation, we found that many LACNs, Brazil especially, have in fact invested substantial time and funds in nationwide HIV prevention and treatment programs and campaigns.2,94 This commitment may have helped this region avoid the severe HIV/AIDS epidemic that now plagues Africa.28 Whereas we applaud the governmental and non-governmental organizations in LACNs for their dedication and sensitivity towards the threat of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we are concerned that these campaigns and interventions are not often being evaluated enough by experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Without data from trials such as these it is difficult to gauge the efficacy of these programs, and time and money could be wasted on inefficacious interventions. As our results suggest, despite the difficulty that ingrained social-cultural beliefs and impoverished environments pose towards HIV prevention, carefully targeted and culturally-sensitive interventions show more promise in promoting condom use in LACNs. While more attention should be paid in the future to groups at greatest need, such as CSWs, MSM, and individuals living in poverty, more effective HIV interventions might also address the social-economic barriers impeding greater sexual health awareness and contraception use. A possible direction for future investigation would be seeing how well structural interventions in tandem with general behavioral interventions reduce sexual risk, and how sustained those behavior change effects are. Greater emphasis should also be placed on elements shown to boost condom intervention success, such as condom distribution, discussion of social-cultural barriers and behavioral skills training in order to curb the incidence of HIV transmission in LACNs.

Figure 1.

Selection process for study inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank study authors who made their data available for this study and Jennifer Ortiz, Natalie D. Smoak, and Amanda Northcutt who assisted in coding the meta-analyses and preparing the database of references. The work also benefited from Marijn de Bruin’s comments.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-MH58563 to B. T. Johnson.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: T. B. Huedo-Medina and B. T. Johnson conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and led the writing of the manuscript. M.H. Boynton, J. M. LaCroix, and M.R. Warren assisted with the acquisition, content coding, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. M. P. Carey assisted with the conceptualization of the study and interpretations of data. All authors provided critical revisions of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors indicate no conflicts of interest.

Conference Presentations: None to date

References

(Asterisks indicate reports with studies included in the meta-analysis.)

- 1.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández MI, Kelly JA, Stevenson LY, et al. HIV prevention programs of nongovernmental organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean: the Global AIDS Intervention Network project. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;17(3):154–162. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darbes LA, Kennedy GE, Peersman G, Zohrabyan L, Rutherford GW. [Accessed November 21, 2007];Systematic review of HIV behavioral prevention research in Latinos. 2002 ( http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite.jsp?page=kb-07-04-11)

- 4.Levy V, Page-Shafer K, Evans J, et al. HIV-related risk behavior among Hispanic immigrant men in a population-based household survey in low income neighborhoods of northern California. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(8):487–490. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000161185.06387.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galanti GA. The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: An overview. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(3):180–185. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodyear RK, Newcomb MD, Allison RD. Predictors of Latino men’s paternity in teen pregnancy: Test of a mediational model of childhood experiences, gender role attitudes, and behaviors. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47(1):116–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marín BV, Gómez CA, Tschann JM, Gregorich SE. Condom use in unmarried Latino men: a test of cultural constructs. J Health Psychol. 1997;16(5):458–467. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marín BV, Tschann JM, Gómez CA, Kegeles SM. Acculturation and gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic white unmarried adults. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(12):1759–1761. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrado EA, Flippen CA, McQuiston C. Use of commercial sex workers among Hispanic migrants in North Carolina: Implications for the spread of HIV. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(4):150–156. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.150.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: Power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):723–749. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez CA, Marín BV. Gender, culture and power: Barriers to HIV prevention strategies. J Sex Res. 1996;33(4):355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marín BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(3):186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marín BV, Gómez CA. Latino culture and sex: Implications for HIV prevention. In: Garcia JG, Zea MC, editors. Psychological interventions and research with Latino populations. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1997. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell LD, Alexander MK, Corbo KF. Developing culture-specific interventions for Latinas to reduce HIV high-risk behaviors. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2000;11(3):70–76. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Díaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: Data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(3):255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Díaz RM, Morales ES, Bein E, Dilán E, Rodríguez RA. Predictors of sexual risk in Latino gay/bisexual men: the role of demographic, developmental, social cognitive and behavioral variables. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1999;21(4):480–501. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marín BV, Gómez CA. Latinos, HIV disease, and culture: strategies for HIV prevention. In: Cohen PT, Sande MA, Volberding PA, editors. The AIDS knowledge base. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co; 1994. pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marín G, Marín BV, editors. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zea MC, Reisen CA, Díaz RM. Methodological issues in research on sexual behavior with Latino gay and bisexual men. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31(3–4):281–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1023962805064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albarracín J, Albarracín D, Durantini M. Effects of HIV-prevention interventions for samples with higher and lower percents of Latinos and Latin Americans: A meta-analysis of change in condom use and knowledge. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):521–543. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9209-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manji A, Peña R, Dubrow R. Sex, condoms, gender roles, and HIV transmission knowledge among adolescents in León, Nicaragua: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):989–995. doi: 10.1080/09540120701244935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prado G, Schwartz SJ, Pattatucci-Aragón A, et al. The prevention of HIV transmission in Hispanic adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(Suppl 1):S43–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piot P, Greener R, Russell S. Squaring the circle: AIDS, poverty, and human development. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):1571–1575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(12):1901–1911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United Nations Development Programme. Statistics of the Human Development Report. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Bank. World Development Indicators 2007. Washington, DC: 2007b. CD-ROM. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: Sustaining effects using an ecological approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(8):888–906. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1996. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. Economic growth and human development. [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1997. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. Human development to eradicate poverty. [Google Scholar]

- 31.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1998. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. Consumption for human development. [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1999. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. Globalization with a human face. [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2000. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. Human rights and human development. [Google Scholar]

- 34.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2001. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. Making new technologies work for human development. [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2002. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. Deepening democracy in a fragmented world. [Google Scholar]

- 36.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2003. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. Millennium development goals: A compact among nations to end human poverty. [Google Scholar]

- 37.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2004. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world. [Google Scholar]

- 38.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2006. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. Beyond scarcity: Power, poverty and the global water crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1988;41(2):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat. 1981;6(2):107–128. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Chacón-Moscoso S. Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):448–467. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson BT, Boynton MH. Cumulating evidence about the social animal: Meta-analysis in social-personality psychology. Pers Soc Psych Comp. 2008;2(2):817–841. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Martín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stram DO. Meta-Analysis of published data using linear mixed-effects model. Biometrics. 1996;52(2):536–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Bronfman M, Leyva R, Negroni MJ. HIV prevention among truck drivers on Mexico’s southern border. Cult Health Sex. 2002;4(4):475–488. [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Givaudan M, Van de Vijver FJR, Poortinga YH, Leenen I, Pick S. Effects of a school-based life skills and HIV-prevention program for adolescents in Mexican high schools. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;37(6):1141–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Givaudan M, Pick S. Evaluación del programa escolarizado para adolescentes: “UN equipo contral el VIH/SIDA”. Interam J Psychol. 2005;39(3):339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Givaudan M, Leenen I, Van de Vijver FJR, Poortinga YH, Pick S. Longitudinal study of a school based HIV/AIDS early prevention program for Mexican adolescents. Psychol Health Med. 2008;13(1):98–110. doi: 10.1080/13548500701295256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Givaudan M, Van de Vijver FJR, Poortinga YH. Identifying precursors or safer-sex practices in Mexican adolescents with and without sexual experience: An exploratory model. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2005;35(5):1089–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Martinez-Donate AP, Hovell MF, Zellner J, Sipan CL, Blumberg EJ, Carrizosa C. Evaluation of two school-based HIV prevention interventions in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico. J Sex Res. 2004;41(3):267–278. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.Patterson TL, Mausbach B, Lozada R, et al. Efficacy of a brief behavioral intervention to promote condom use among female sex workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2051–2057. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53*.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Fraga M, Bucardo J, Davila-Fraga W, Strathdee SA. An HIV-prevention intervention for sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico: A pilot study. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2005;27(1):82–100. [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Pick de Weiss S, Andrade-Palos P, Townsend J, Givaudan M. Evaluación de un programa de educación sexual sobre conocimientos, conducta sexual y anticoncepción en adolescentes. Salud Mental V. 1994;17(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Walker D, Gutierrez JP, Torres P, Bertozzi SM. HIV prevention in Mexican schools: Prospective randomized evaluation of intervention. Br Med J. 2006;332:1189–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38796.457407.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Ferreira-Pinto JB, Ramos R. HIV/AIDS prevention among female sexual partners of injection-drug users in Ciudad-Juarez, Mexico. AIDS Care. 1995;7(4):477–488. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.Antunes M, Stall R, Paiva V, et al. Evaluating an AIDS sexual risk reduction program for young adults in public night schools in Sao Paulo, Brazil. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl 1):S121–S127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Hearst N, Lacerda R, Gravato N, Hudes ES, Stall R. Reducing AIDS risk among port workers in Santos, Brazil. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(1):76–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59*.Magnani RJ, Gaffikin L, Aquino EML, Seiber EE, Almeida MC, Lipovsek V. Impact of an integrated adolescent reproductive health program in Brazil. Stud Fam Plan. 2001;32(3):230–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60*.McBride DC, Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Terry YV, Van Buren H. The impact of an HIV risk-reduction program among street drug users in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Am Behav Sci. 1998;41(8):1171–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 61*.Sampaio M, Brites C, Stall R, Hudes ES, Hearst N. Reducing AIDS risk among men who have sex with men in Salvador, Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(2):173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Egger M, Pauw J, Lopatatzidis A, Medrano D, Paccaud F, Smith GD. Promotion of condom use in a high-risk setting in Nicaragua: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9221):2101–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02376-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63*.Pauw J, Ferrie J, Villegas RR, Martínez JM, Gorter A, Egger M. A controlled HIV/AIDS-related health education programme in Managua, Nicaragua. AIDS. 1996;10(5):537–544. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199605000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64*.Calderón E, López M, Bonilla N. Prevención de la transmisión sexual del SIDA mediante un trabajo grupal de cambio de actitudes. Rev Latinoam Sexol. 1991;2:123–136. [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Garcia-Bernal R, Castro JA, Caamano JM, Klaskala WI. Casual sex and condom use: An impact evaluation study in Bogota, Colombia. The XII International AIDS Conference; Geneva, Switzerland. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Colón HM, Robles RR, Freeman D, Matos T. Effects of a HIV risk reduction education program among injection drug users in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 1993;12(1):27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colón HM, Sahai H, Robles RR, Matos TD. Effects of a community outreach program in HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users in San Juan, Puerto Rico: An analysis of trends. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7(3):195–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.Robles RR, Marrero CA, Matos TD, et al. Factors associated with changes in sex behaviour among drug users in Puerto Rico. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):329–338. doi: 10.1080/713612417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Barros T, Barreto D, Pérez F, et al. Un Modelo de prevención primaria de las enfermedades de transmisión sexual y del VIH/SIDA en adolescentes. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2001;10(2):86–94. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892001000800003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70*.Cáceres CF, Rosasco AM, Mandel JS, Hearst N. Evaluating a school-based intervention for STD/AIDS prevention in Peru. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15(7):582–591. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90143-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71*.Welsh JM, Puello E, Meade M, Kome S, Nutley T. Evidence of diffusion from a targeted HIV/AIDS intervention in the Dominican Republic. J Biosoc Sci. 2001;33(1):107–119. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72*.Iurcovich M, Lourie KJ, Brown LK. The AIDS prevention training program for high school students in Buenos Aires, Argentina. J HIV/AIDS Prev Educ Adolesc Child. 1998;2(3–4):91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 73*.Kinsler J, Sneed CD, Morisky DE, Ang A. Evaluation of a school-based intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention among Belizean adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(6):730–738. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74*.Deschamps MM, William J, Hafner A, Johnson WD. Heterosexual transmission of HIV in Haiti. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(4):324–330. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75*.Fox LJ, Bailey PE, Clarke-Matínez KL, et al. Condom use among high-risk women in Honduras: Evaluation of an AIDS prevention program. AIDS Educ Prev. 1993;5(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76*.Levine WC, Revollo R, Kaune V, et al. Decline in sexually transmitted disease prevalence in female Bolivian sex workers: Impact of an HIV prevention project. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1899–1906. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levine WC, Higueras G, Revollo R, et al. Rapid decline in sexually transmitted disease prevalence among brothel-based sex workers in La Paz, Bolivia: The experience of Proyecto Contra SIDA, 1992–1995. The XI International AIDS Conference; Vancouver, Canada. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Egger M, Davey G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, Cowan F. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: A systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(5):659–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoffman K, Centeno MA. The lopsided continent: Inequality in Latin America. Annu Rev Sociol. 2003;29:363–390. [Google Scholar]

- 83.MkNelly B, Dunford C. Freedom from Hunger Research Paper No. 5. Freedom from Hunger; Davis, California: 1999. Impact of credit with education on mothers and their young children’s nutrition: CRECER credit with education program in Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson BT, Redding CA, Diclemente RJ, et al. A network-individual-resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mitchell SH, Schoel C, Stevens AA. Mechanisms underlying heightened risk taking in adolescents as compared with adults. Psychol Bull. 2008;15(2):272–277. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.2.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reyna VF, Farley F. Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making: Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2006;7(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LAJ. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: A research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Cary MP. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for HIV in adolescents: A meta-analysis of trials, 1985–2008. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Earl A, Albarracín D. Nature, decay, and spiraling of the effects of fear-inducing arguments and HIV counseling and testing: a meta-analysis of the short- and long-term outcomes of HIV-prevention interventions. J Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):496–506. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Smoak ND, LaCroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(4):492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Experimental component analysis of a behavioral HIV-AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(4):687–693. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho MH. Test of major assumptions about behaviour change: a comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):356–397. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bastos FI, Cáceres C, Galvão J, Veras MA, Castilho EA. AIDS in Latin America: Assessing the current status of the epidemic and the ongoing response. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(4):729–737. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nunn AS, da Fonseca EM, Bastos FI, Gruskin S. AIDS treatment in Brazil: Impacts and challenges. Health Aff. 2009;28(4):1103–1113. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]