Abstract

(R,R’)-4’-methoxy-1-naphthylfenoterol [(R,R’)-MNF] is a highly-selective β2 adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) agonist. Incubation of a panel of human-derived melanoma cell lines with (R,R’)-MNF resulted in a dose- and time-dependent inhibition of motility as assessed by in vitro wound healing and xCELLigence migration and invasion assays. Activity of (R,R’)-MNF positively correlated with the β2-AR expression levels across tested cell lines. The anti-motility activity of (R,R’)-MNF was inhibited by the β2-AR antagonist ICI-118,551 and the protein kinase A inhibitor H-89. The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin and the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor Ro 20–1724 mimicked the ability of (R,R’)-MNF to inhibit migration of melanoma cell lines in culture, highlighting the importance of cAMP for this phenomenon. (R,R’)-MNF caused significant inhibition of cell growth in β2-AR-expressing cells as monitored by radiolabeled thymidine incorporation and xCELLigence system. The MEK/ERK cascade functions in cellular proliferation, and constitutive phosphorylation of MEK and ERK at their active sites was significantly reduced upon β2-AR activation with (R,R’)-MNF. Protein synthesis was inhibited concomitantly both with increased eEF2 phosphorylation and lower expression of tumor cell regulators, EGF receptors, cyclin A and MMP-9. Taken together, these results identified β2-AR as a novel potential target for melanoma management, and (R,R’)-MNF as an efficient trigger of anti-tumorigenic cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling in β2-AR-expressing lesions.

Keywords: beta2 adrenoreceptor selective agonist, melanocyte, metastasis, beta blocker, migration, melanocortin 1 receptor

1 Introduction

(R,R’)-4’-methoxy-1-naphthylfenoterol [(R,R’)-MNF] is a potent (EC50 = 3.9 nM) and selective β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) agonist with a 573-fold greater selectivity for β2-AR relative to β 1-AR [1]. The β2-AR agonist properties of (R,R’)-MNF have been associated with the inhibition of mitogenesis in 1321N1 cells, a human-derived astrocytoma cell line [2]. [3H]-thymidine incorporation was decreased by (R,R’)-MNF in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 3.98 nM. This effect was attenuated by the β2-AR antagonist ICI-118,551 and the protein kinase A inhibitor H-89 and mimicked by the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin [2]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in addition to acting as a β2-AR agonist, (R,R’)-MNF is also an antagonist of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR55 and promotes growth inhibition and apoptosis both in a human-derived hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell line and a human-derived pancreatic cancer (PANC-1) cell line [3].

In the present study we have investigated the β2-AR agonist properties of (R,R’)-MNF on the proliferation and motility of human-derived melanoma cell lines. This pharmacological activity of (R,R’)-MNF was studied as β2-AR is expressed in all types of normal skin cells [4–7]. However, until recently, its importance in skin biology has been largely overlooked. β2-AR has been identified as a negative regulator of wound healing [8], a biological process that resembles tumor development [9]. Physical damage to the epithelium induces activation of keratinocytes, transiently turning them into hyperproliferative and motile cells targeted to heal the wound [10]. When the site of injury is sealed the keratinocytes undergo apoptosis-like process of differentiation aimed to restore the stratified structure of epithelial tissue [10]. In case of tumor formation the proliferative signaling is sustained and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition occurs to initiate invasion and metastasis [9]. Because β2-AR activation has been linked with decreased wound healing and reduced migratory capabilities of normal keratinocytes [11–14], it was tempting to speculate that activation of β2-AR with (R,R’)-MNF may contribute to inhibition of proliferation and motility in malignant skin tumor cells.

Melanoma constitutes only a small fraction of skin cancer cases, but it accounts for the majority of all skin cancer-associated deaths. Individuals diagnosed with early stage (IA and IB) melanoma have a 5-year survival rate of about 90%. In case of late diagnosis (stage IV), the 5-year survival rate drops to a grim 10% [15]. In this work, we investigated the ability of (R,R’)-MNF to inhibit invasion and prosurvival signaling in a panel of human melanoma cell lines via selective activation of β2-AR. UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cell lines were chosen for this study due to their metastatic capacity [16]. All three cell lines have been previously classified, based on gene expression profiling, into the subset of invasive melanomas characterized by tubular network formation, ability to contract collagen gels and high motility [17].

Here, we report new insights into (R,R’)-MNF activity that enable us to better understand the process of metastasis inhibition in melanoma cells. We found that the accumulation of cAMP and subsequent PKA activation are crucial steps that drive the anti-migratory signaling of β2-AR. Inhibition of cellular motility and proliferation in response to (R,R’)-MNF treatment was accompanied by time- and dose-dependent reduction in MEK/ERK activation and inhibition in protein translation through increased phosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2).

2 Materials and Methods

Reagents

(R,R’), (S,R ’), (R,S’) and (S,S’) stereoisomers of MNF as well as (R,R’)-Fenoterol (Fen) were synthesized according to previously reported synthesis scheme [1, 18]. Forskolin, NKH-477, Ro 20–1724, (R)-(−)-rolipram, zardaverine, H-89 and KT 5720 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). Epinephrine, isoproterenol, ICI-118,551 and CGP-20712A were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tritiated compounds, [3H]CGP-12177 (41.6 Ci/mmol), [3H]thymidine (10 Ci/mmol) and [35S]-protein labeling mix (0.1 Ci/mmol) were from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture

Human UACC-647, UACC-903 and M93-047 melanoma cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (all from Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). All cell lines were cultured in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Scratch assay

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and were cultured in complete medium until confluent. Uniform scratch wounds were made on the monolayer cultures using polyethylene cell scraper (Corning, Tewksbury MA, USA). The cells were washed twice with serum-free medium and challenged with compounds of interest or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Images were captured at the onset of the treatment and at selected time-points using an AxioCam HRc digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) attached to an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss). TScratch 1.0 picture analysis software was employed to measure the wound surface area [19]. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times in quadruplicates.

Migration and invasion

Migration and invasion assays were performed using xCELLigence RTCA Analyzer (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. Cells were serum-starved for 20 h, seeded out to the upper chamber of Cell Invasion and Migration (CIM) plate (ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well, treated with (R,R’)-MNF (from 100 pM to 10 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%), and allowed to migrate via microporous polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane towards the lower chamber of the CIM plate filled with culture media containing 10% FBS. In other series of experiments the cells were pre-treated for 45 min with ICI-118,551 (50 nM), CGP-20712A (50 nM), Ro 20–1724 (10 µM), (R)-(−)-rolipram (10 µM), zardaverine (10 µM), H-89 (20 µM), KT 5720 (10 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) followed by the addition of (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM), forskolin (10 µM), NKH-477 (10 µM), or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) where indicated. In case of invasion assessment, the membrane in CIM plate was covered with Matrigel (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) reconstituted in serum-free media (1:200, v:v). Impedance of the gold microelectrode array attached to the bottom side of the membrane was monitored independently for each well and converted by RTCA Software v1.2 (ACEA Biosciences) to cell index (CI), a dimensionless parameter, which was directly proportional to the total area of microelectrodes populated by the cells. Readouts were performed every 10 min for up to 50 h. CI values were plotted against time, fitted to four-parameter sigmoidal equation and half-time of migration/invasion (half maximal effective time, ET50) was calculated for each experimental condition using GraphPad Prism v5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Real-time proliferation measurement

UACC-647, M93-047 or UACC-903 melanoma cells were seeded in an E plate (ACEA Biosciences) at a density of 4 × 103 cells per well in complete RPMI medium (10% FBS) and cultured in the xCELLigence instrument where impedance was recorded every 15 min. After 15 h of incubation the CI was set to 1 and the culture media was replaced with RPMI containing reduced serum (2% FBS) together with 100 nM (R,R’)-MNF or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Impedance was measured for an additional 48 h.

[3H]-Thymidine incorporation

UACC-647 cells were plated in a 96-well plate at 5 × 103 cells per well. After 24 h the cells were pretreated with ICI-118,551 (100 nM) or vehicle (H2O, 0.1%) followed by the addition of increasing concentrations of (R,R’)-MNF. Forty-eight hours later, 0.25 µCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well. The cells were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C, at which point 30 µL of 10 × trypsin was added, and the resuspended cells were harvested with a Tomtec 96 harvester through glass fiber filters. DNA-associated radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously [3]. The antibodies developed against β2-AR (#ab40834) and β-actin (#ab6276) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Anti-EGFR (#sc-03), anti-HSP90 (#sc-13119), anti-phospho-c-Raf (#sc-21833-R) and anticyclin A (#sc-751) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies detecting phospho-ERK1/2 (#4376), total ERK2 (#9108), phospho-MEK1/2 (#9121), total MEK1/2 (#9122), phospho-eEF2 (#2332), total eEF2 (#2331), total c-Raf (#9422) and phospho-PKA-substrates (#9621) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The band intensities were quantified by means of volume densitometry using Fiji image processing package [20].

ELISA

Levels of ERK1/2 and its phosphorylated form were determined using PathScan ELISA kits (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Global [35]S-labeled protein translation assay

UACC-647 and UACC-903 melanoma cells were seeded in 6-well plates, cultured for 24 h and then starved for 3 h. After a series of washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were incubated in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium without methionine and cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich). Then, cells were treated with (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) or incubated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) for 15 min followed by [35S]Met/Cys labeling for 30 min. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and autoradiography was performed. The membrane was later probed with anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal protein loading.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v5.03. Data were plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless noted otherwise. Differences between the means of treatments were evaluated using unpaired Student’s t-test and/or one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s test. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were calculated by fitting experimental values to sigmoidal, biphasic or bell-shaped equation. Significance was designated as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001.

3 Results

3.1 (R,R’)-MNF inhibits in vitro wound healing in melanoma cell lines

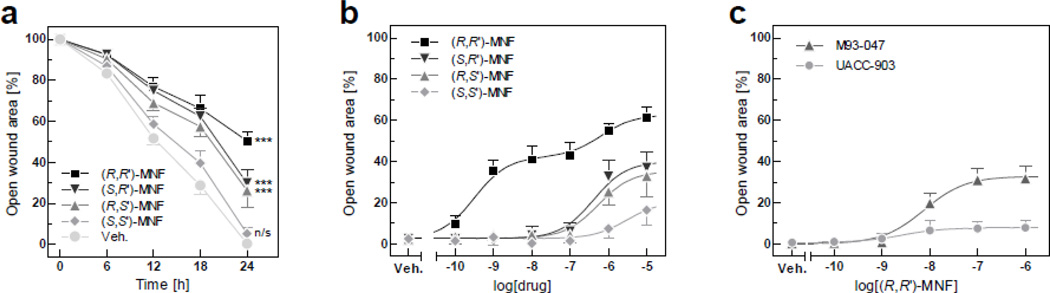

Earlier studies showed that the β2-AR agonistic activity of MNF and other Fen derivatives strongly depends on stereoconfiguration of the molecule [1, 2, 21]. The in vitro scratch assay was performed to assess the inhibitory potential of MNF stereoisomers against melanoma cell motility. Time-course analysis revealed that a 24-h incubation was required for the vehicle-treated UACC-647 cells to fully seal the wound site (Fig. 1a). (R,R’)-MNF (1 µM) markedly slowed down the process of wound healing – around 50% of initial gap area remained unsealed after 24 h of treatment. Challenge with (S,R’) and (R,S’) enantiomers was less effective compared to (R,R’)-MNF, with roughly 70% closure of the wound at 24 h. (S,S’)-MNF did not significantly alter the motility rate of UACC-647 cells as compared to vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 1a). It would appear therefore that the (R,R’) stereoisomer of MNF is the most potent inhibitor of wound healing in UACC-647 cells.

Figure 1. (R,R’)-MNF inhibits in vitro wound healing in cultured melanoma cells.

(a) Scratch assays were performed with UACC-647 cells in the presence of (S,S’), (S,R’), (R,S’) and (R,R’) stereoisomers of MNF (1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). Pictures were taken immediately after wound generation and every 6 h until the closure of the scratch wound in vehicle-treated cells (24 h). Open wound areas were measured over time and plotted. Values were gathered from three independent experiments carried out in quadruplicates (n = 12). Data are expressed as mean ± 95% confidence interval. Effects of MNF isomers versus control were statistically evaluated at 24 h time-point using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. ***, P < 0.001; n/s, not significant. (b) UACC-647 cells were subjected to scratch wound and treated with 100 pM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 µM and 10 µM of (R,R’), (S,R’), (R,S’) and (S,S’) stereoisomers of MNF or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). Dose-dependent effects of MNF stereoisomers were evaluated using non-linear regression (see section 3.1 for IC50 values). (c) Capacity of (R,R’)-MNF to inhibit wound healing was assessed in M93-047 and UACC-903 cells. The relative wound surface area of 12 independent observations at the 24 h time-point is plotted.

Dose-dependent effects of MNF isomers on UACC-647 motility were studied. Wound sites were pictured 24 h after stimulation with doses of MNF isomers ranging from 100 pM to 10 µM (Fig. 1b). (R,R’)-MNF displayed a biphasic sigmoidal dose-response characterized by sub-nanomolar and low micromolar activities, with IC50 = 0.32 nM and 0.64 µM, respectively. Treatment with (S,R’), (R,S’) and (S,S’)-MNF resulted in standard sigmoidal dose-responses, with IC50 of 0.41, 0.55 and 3.06 µM, respectively (Fig. 1b).

Dose ranging studies with (R,R’)-MNF resulted in comparable half-maximal inhibitory concentrations of 7.60 and 2.61 nM for M93-047 and UACC-903 cell lines, respectively (Fig. 1c). However, only 8% of initial wound area remained open after a 24-h treatment of UACC-903 cells with 1 µM (R,R’)-MNF compared to 32% in M93-047 cells (Fig. 1c). Representative pictures for all in vitro wound healing experiments described in this section are shown in Fig. S1.

3.2 (R,R’)-MNF inhibits melanoma cell migration and invasion

UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cell lines are highly metastatic [22, 23]. To get more insight into the temporal effects of (R,R’)-MNF on the mobility of these cell lines, real-time measurements of migration and invasion were carried out employing xCELLigence system. In this approach, the cells were treated with a range of (R,R’)-MNF concentrations and allowed to migrate through unmodified or Matrigel-coated microporous membrane towards chemoattractant. The amount of cells that traveled through the membrane was continuously recorded (Fig. S2).

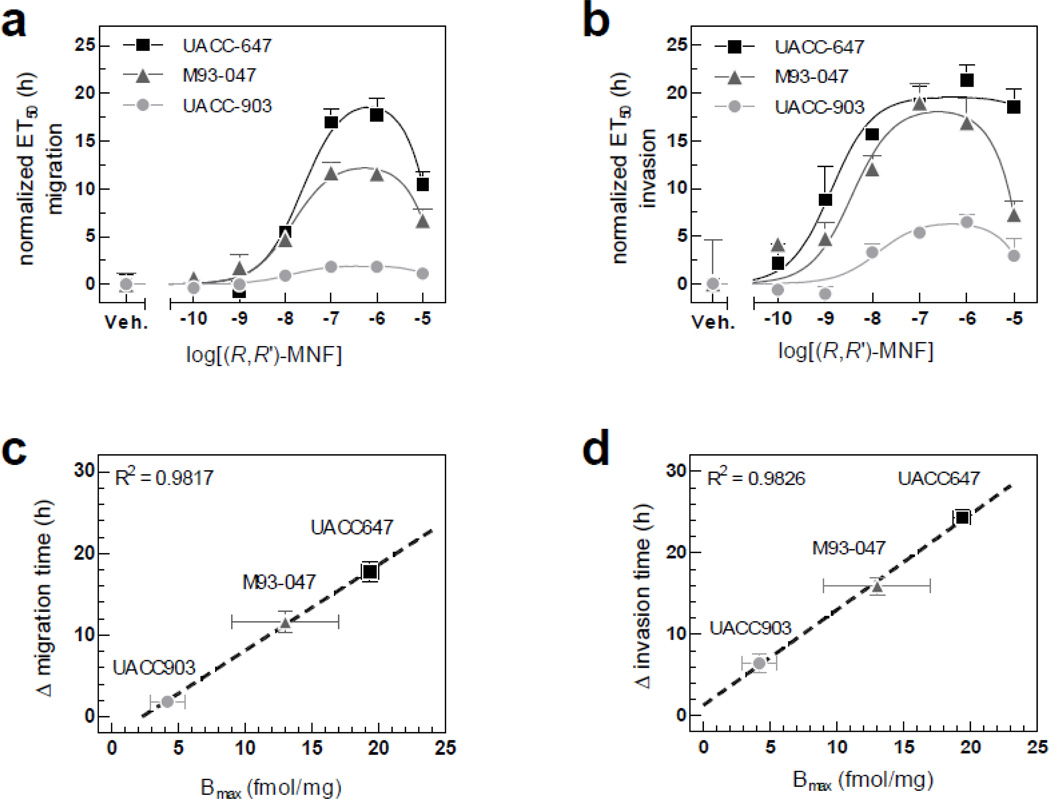

(R,R’)-MNF dose-dependently inhibited the migration of UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cells through microporous PET membrane, with IC50 values of 23.82, 14.62 and 12.94 nM, respectively (Fig. 2a). Despite comparable half maximal inhibitory concentrations, the delay in migration in response to (R,R’)-MNF differed significantly across cell lines, ranging from 17.7 ± 1.3 h in UACC-647 cells to 11.6 ± 1.3 h in M93-047 cells, and only 1.8 ± 0.2 h in UACC-903 cells (Fig. S2a, c, e).

Figure 2. (R,R’)-MNF activity on melanoma cell migration depends on the expression of β2-AR.

(a) Migration of UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 melanoma cells was studied using xCELLigence system. Serum-depleted cells were treated with increasing concentrations of (R,R’)-MNF (from 100 pM to 10 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) and allowed to migrate via microporous PET membrane towards 10% FBS. CI was recorded over time (see Fig. S2) and was used to calculate ET50 values. All ET50 values were normalized to the data obtained for vehicle-treated cells. Bell-shaped curve was fitted to the data and IC50 values were calculated. (b) Invasion of UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cells through Matrigel coating was studied in parallel using the same approach. (c) Linear regression model was used to correlate maximal delay in migration time (Δ migration time) caused by (R,R’)-MNF with expression level of β2-AR (Bmax). (d) Analogously, (R,R’)-MNF-dependent delay in invasion through Matrigel was correlated with expression level of β2-AR.

Invasion assays were then carried out by allowing cells to infiltrate the Matrigel-coated PET membrane. (R,R’)-MNF slowed down the invasion of UACC-647 cells through Matrigel by 21.3 ± 0.9 h, with IC50 of 1.35 nM (Fig. S2b and Fig. 2b). Moreover, the process of invasion was delayed by 19.0 ± 1.1 h in M93-047 cells, with IC50 of 3.75 nM (Fig. S2d and Fig. 2b). UACC-903 cells were the least responsive to (R,R’)-MNF treatment, with the delay in the invasion of only 6.5 ± 1.2 h, with IC50 of 13.34 nM (Fig. S2f and Fig. 2b). Noteworthy, in all motility assays described in sections 3.1 and 3.2 the effective concentrations of (R,R’)-MNF were in nanomolar range and were not cytotoxic (Fig. S3).

Expression of β2-AR in UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cell lines was determined by immunoblotting (Fig. S4a) and membrane receptor binding assay (Fig. S4b). The results confirmed β2-AR expression, although to varying degree across the tested cell lines. The density of β2-AR (Bmax) versus shift in time of migration or invasion in response to (R,R’)-MNF were curve fitted to straight-line model, and presented in Fig. 2c–d. Importantly, β2-AR expression positively and significantly correlated with (R,R’)-MNF’s ability to inhibit migration (Fig. 2c) and invasion (Fig. 2d) of melanoma cells.

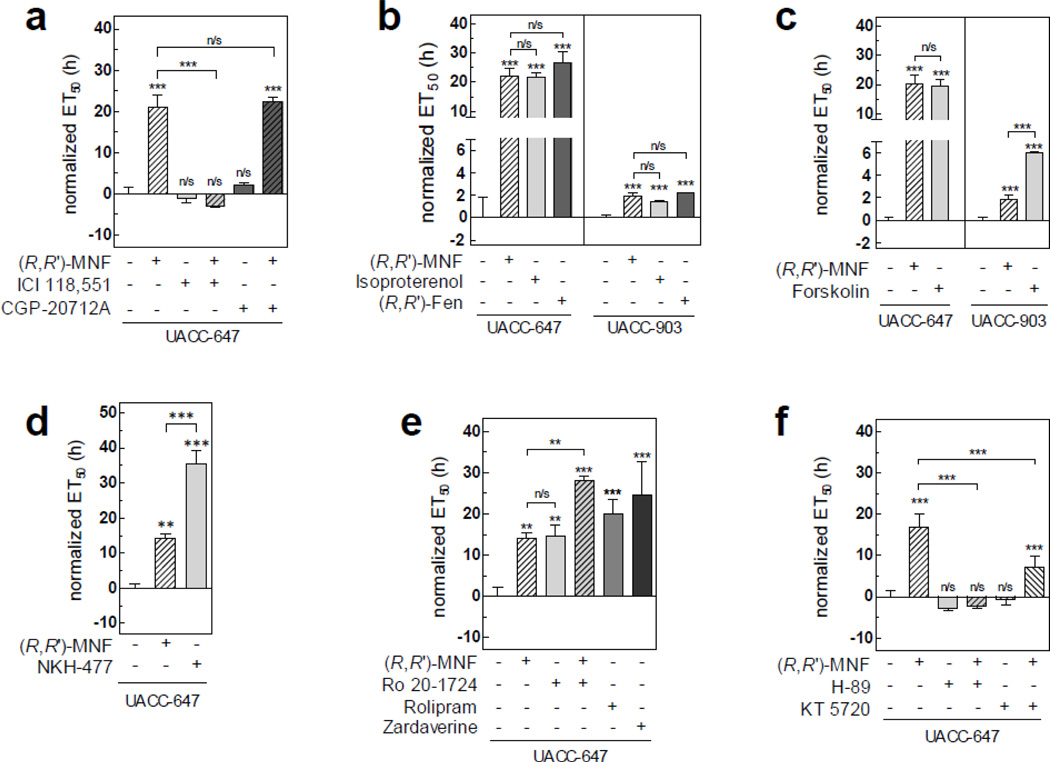

3.3 β2-AR/AC/cAMP/PKA signaling axis drives the anti-migratory activity of (R,R)-MNF

(R,R’)-MNF is a specific agonist of β2-AR over β 1-AR [1]. To test the involvement of these receptors in the inhibitory activities of (R,R’)-MNF on tumor cell migration, UACC-647 cells were pre-treated with CGP-20712A (50 nM), a selective antagonist of β1-AR [24], and ICI-118,551 (50 nM), a selective antagonist of β2-AR [24], prior to stimulation with (R,R’)-MNF. Pharmacological blockage of β2-AR, but not β1-AR, was sufficient to completely inhibit the anti-migratory activity of (R,R’)-MNF, indicating that β2-AR constitutes the molecular point of entry for (R,R’)-MNF-dependent signaling in UACC647 cells (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. (R,R’)-MNF acts via cAMP to inhibit melanoma cell migration.

UACC-647 or UACC-903 melanoma cells were serum-starved for 20 h and their migratory capabilities were assessed using xCELLigence system. Recorded CI values that were used to calculate ET50 values are depicted on Fig. S5. (a) Serum-starved UACC-647 cells were pre-treated with ICI-118,551 (50 nM) or CGP-20712A (50 nM) for 45 min followed by the addition of (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) and allowed to migrate via PET membrane towards 10% FBS. Serum-free medium was used as negative control (Neg. ctrl.). ET50 was calculated for each treatment and normalized to vehicle. (b) Serum-depleted UACC-647 and UACC-903 cells were treated with β2-AR agonists: (R,R’)-MNF, isoproterenol or (R,R’)-Fen (all at 100 nM concentration). Migration through PET membrane was measured. (c) Activity of forskolin (10 µM) was compared with the anti-migratory properties of (R,R’)-MNF in UACC-647 and UACC-903 cells. Normalized ET50 values are given. (d) UACC-647 cells were serum-starved and treated with NKH-477 (10 µM), (R,R’)-MNF or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). (e) UACC-647 cells were incubated with (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM), Ro 20-1724 (10 µM) or combination of the two. Additionally, the cells were treated with Rolipram (10 µM) or Zardaverine (10 µM). ET50 values were calculated. (f) UACC-647 cells were serum-depleted and pre-treated with H-89 (20 µM) or KT 5720 (10 µM) followed by the addition of (R,R’)-MNF or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). Anti-migratory effect of tested compounds is presented as ET50 values. All experiments were performed in triplicates. Error bars represent SD. Statistical evaluation of either ‘treatments versus control cells’ (symbols directly above the bars) or ‘differences between the indicated treatments’ was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; n/s, not significant.

To further confirm that the β2-AR is a regulator of melanoma cell migration, the activity of two additional β2-AR agonists was assessed using xCELLigence system. Isoproterenol (100 nM) and (R,R’)-Fen (100 nM) mimicked (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) and significantly delayed the migration of UACC-6047 cells by 21.63 ± 1.54 and 26.47 ± 3.75 h, respectively (Fig. 3b). In UACC-903 cells, which express low levels of β2-AR (Fig. S4), the activity of isoproterenol and (R,R’)-Fen was comparable to that of (R,R’)-MNF (Fig. 3b).

Activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) and subsequent increase in cellular cAMP levels is a canonical signaling outcome triggered upon agonist binding to β2-AR [25]. It is noteworthy that accumulation of cAMP has been previously linked with decreased metastatic potential in melanomas [26]. (R,R’)-MNF stimulated the production of cAMP in UACC-647 cells, with EC50 of 135.0 nM (Fig. S6a). Similarly, treatment with forskolin, a direct activator of AC, also led to a rise in cAMP levels (EC50 = 20.39 µM, Fig. S6b). Moreover, forskolin (10 µM) caused a 19.4 ± 2.4 h delay in UACC-647 cell migration as compared to vehicle-treated cells, which was similar to the effect observed with 100 nM (R,R’)-MNF (Fig. 3c). The water-soluble forskolin analogue, NKH-477 (10 µM), was even more potent in slowing cell migration down by more than 35.3 ± 4.0 h (Fig. 3d).

Treatment of UACC-903 cells with forskolin led to rise in cAMP production, with EC50 = 12.90 µM (Fig. S6c). Furthermore, forskolin (10 µM) was significantly more potent than (R,R’)-MNF in delaying UACC-903 cell migration by bypassing the low β2-AR expression in these cells. When compared to vehicle-treated UACC-903 cells, the delay caused by (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) was 1.85 ± 0.20 h versus the 6.03 ± 0.30 h elicited by forskolin (Fig. 3c).

Intracellular concentration of cAMP is negatively regulated by phosphodiesterases (PDEs), a family of enzymes hydrolyzing cyclic nucleotides [27]. Interestingly, expression of cAMP-specific PDE4 is often upregulated in melanomas [28]. We found that pretreatment of UACC-647 cells with a panel of selective PDE4 inhibitors [Ro 20–1724 (10 µM), (R)-(−)-rolipram (10 µM) or zardaverine (10 µM)] delayed the migration rate of UACC-647 cells by 14.5 ± 2.7, 20.0 ± 3.5 and 24.6 ± 8.1 h, respectively (Fig. 3e). The combination of Ro 20–1724 (10 µM) and (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) had an additive inhibitory effect on the migration of UACC-647 cells, causing a 28.1 ± 1.0 h delay over control cells (Fig. 3e).

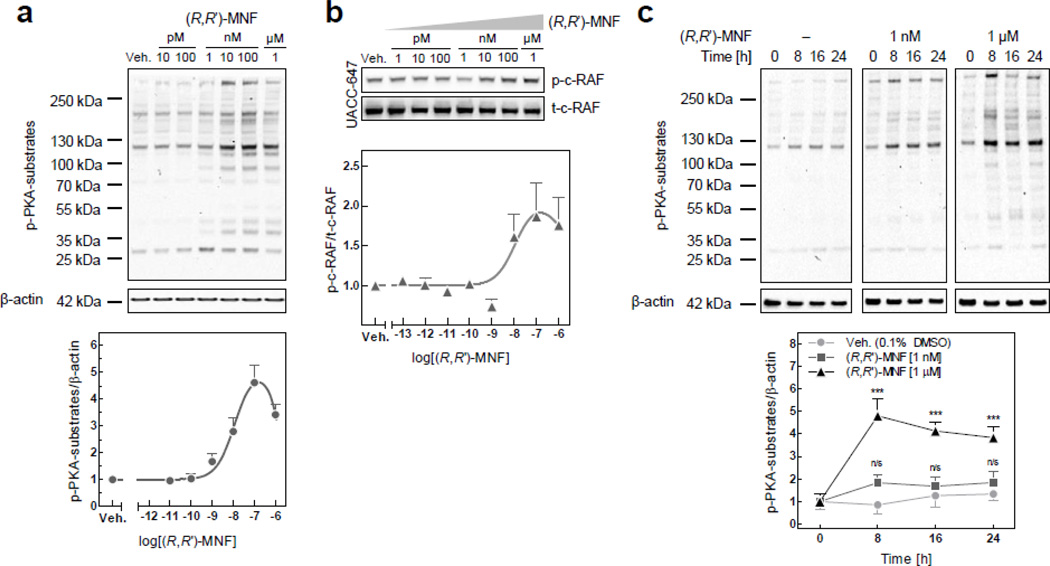

Activation of protein kinase A (PKA) requires the binding of cAMP to its regulatory subunits. Pretreatment of UACC-647 cells with the specific PKA inhibitors, H-89 (20 µM) and KT 5720 (10 µM), abolished the anti-migratory activity of MNF (Fig. 3f), supporting the notion that PKA plays an important role in transducing (R,R’)-MNF signaling. Next, immunoblot analyses were performed with an antibody specific for PKA protein substrates using total cell lysates prepared from UACC-647 cells (Fig. 4). (R,R’)-MNF dose-dependently increased PKA-mediated phosphorylation of protein substrates, with EC50 of 11.75 nM (Fig. 4a). These phosphorylated proteins ranged in size from 25 kDa to over 250 kDa representing a broad spectrum of PKA substrates. PKA targets and inhibits a 74-kDa kinase known as c-Raf or Raf-1 by phosphorylation at Ser259 [29, 30]. (R,R’)-MNF caused dose-dependent phosphorylation of c-Raf at this inhibitory residue (Fig. 4b). (R,R’)-MNF (1 µM) treatment sustained the elevated phosphorylation levels of PKA protein substrates over a 24-h period (Fig. 4c). Of significance, cell pretreatment with H-89 (20 µM) completely abolished the ability of (R,R’)-MNF to induce PKA protein substrate phosphorylation (Fig. S7a). Similarly to (R,R’)-MNF, treatment with isoproterenol (1 µM) or epinephrine (1 µM) induced rapid phosphorylation of PKA targets in UACC-647 cells (Fig. S7b).

Figure 4. (R,R’)-MNF activates PKA.

(a) UACC-647 cells were serum-starved for 3 h and treated for 15 min with increasing concentrations of (R,R’)-MNF (10 pM – 1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). PKA activity was assessed by western blotting using antibody detecting phosphorylated substrates of PKA. β-actin was used as loading control. Intensities of all phospho-PKA substrate bands were measured, normalized to β-actin and plotted. (b) Serum-depleted UACC-647 cells were challenged with (R,R’)-MNF (1 pM - 1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). Expression and phosphorylation pattern of c-Raf at inhibitory Ser259 was determined by western blotting. (c) Serum-starved UACC-647 cells were treated with (R,R’)-MNF (1 nM or 1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) for 0, 8, 16 or 24 h. Levels of phosphorylation of PKA targets were plotted over time and statistically evaluated using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test. ***, P < 0.001; n/s, not significant (versus control cells).

3.4 (R,R’)-MNF reduces melanoma cell proliferation

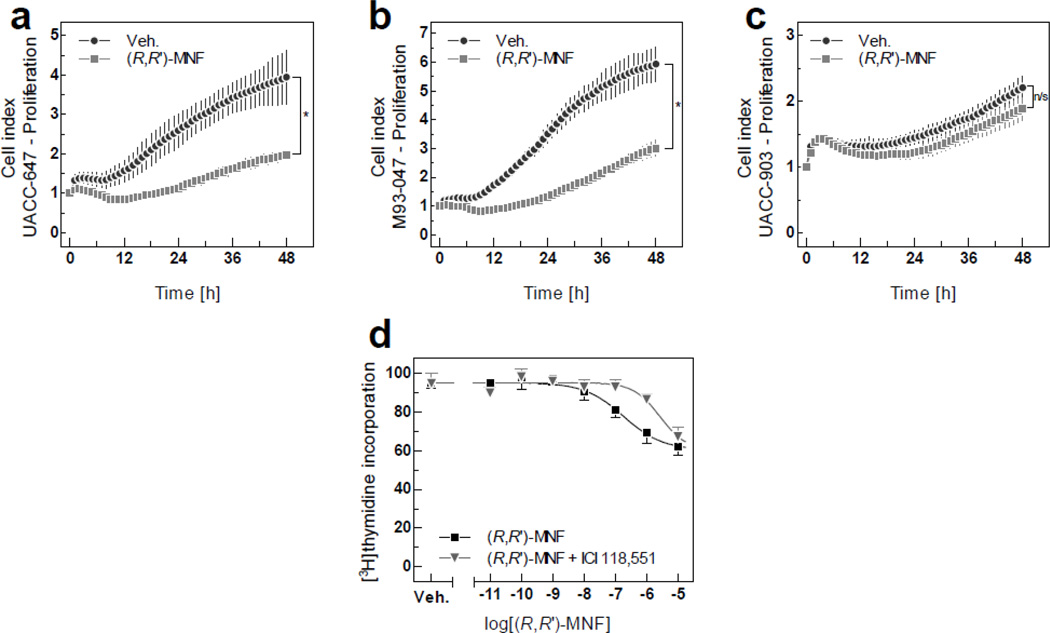

(R,R’)-MNF and other fenoterol derivatives were previously found to inhibit proliferation of cancer cell lines of different origin [2, 31, 32]. When cell proliferation assays were performed using xCELLigence system, significant reduction in growth rate was observed both in UACC-647 cells (50.3% decrease, Fig. 5a) and M93-047 cells (49.3% decrease, Fig. 5b) after 48 h of treatment with 100 nM (R,R’)-MNF. However, UACC-903 cells were unresponsive to the anti-proliferative activity of (R,R’)-MNF, likely due to their low levels of β2-AR expression (Fig. 5c). Observed changes in impedance signals were not associated with significant changes in cell size, confirming that readouts from xCELLigence system truly resulted from altered growth rate and not from changes in cellular morphology (Fig. S8).

Figure 5. Anti-mitogenic activities of (R,R’)-MNF.

Proliferation of human melanoma cell lines in culture was monitored in real-time using xCELLigence system. The UACC-647 (a), M93-047 (b) and UACC-903 (c) cells were cultured for 15 h followed by treatment with 100 nM (R,R’)-MNF or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). Impedance was recorded every 15 min., but to improve the clarity of the graphs only every fourth readout was plotted. Data show the average ± SD of three independent measurements. Differences between CI values for (R,R’)-MNF-treated and control cells were statistically evaluated using Student’s t-test. *, P < 0.05; n/s, not significant. (d) UACC-647 cells were pretreated with ICI-118,551 (100 nM) or vehicle (H2O) for 30 min followed by a 48-h incubation with increasing concentrations of (R,R’)-MNF. Cellular proliferation was measured after subsequent addition of [3H]thymidine for 4 h (see Materials and Methods for further details). Data show the average ± SD of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate wells.

To further corroborate the anti-proliferative properties of (R,R’)-MNF, dose-ranging experiments based on [3H]thymidine incorporation were performed in UACC-647 cells. (R,R’)-MNF inhibited the uptake of radiolabelled thymidine by 40.8 ± 1.8 %, with IC50 of 184.41 nM (Fig. 5d). Inhibition of β2-AR activity with ICI-118,551 abrogated the anti-mitogenic effect of (R,R’)-MNF, which was correlated with an increase of the IC50 value to 2.62 µM (Fig. 5d). Addition of ICI-118,551 alone had no effect on the [3H]thymidine uptake in UACC-647 cells (Fig. 5d).

Consistent with the anti-proliferative activity of (R,R’)-MNF, we observed significant reduction in the expression and/or activity of key signaling proteins implicated in the control of cell cycle, proliferation and motility, including cyclin A, EGF receptor and MMP-9, in response to (R,R’)-MNF treatment (Fig. S9).

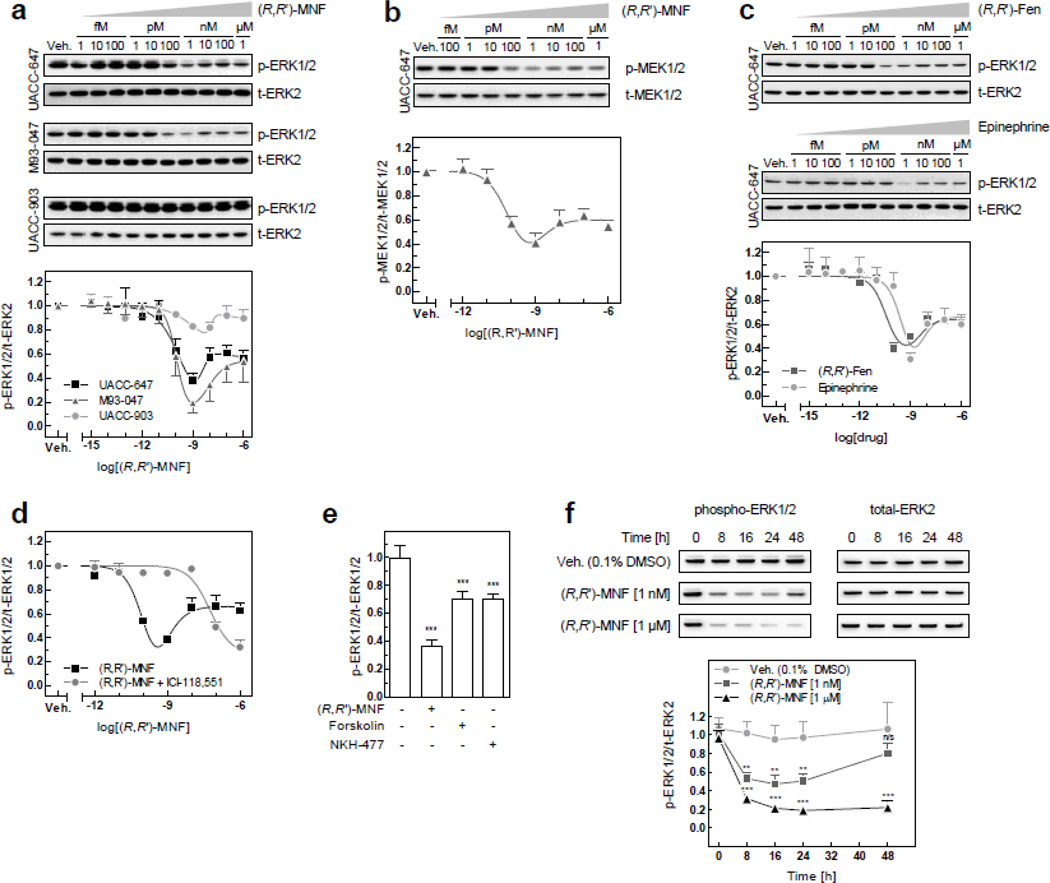

3.5 (R,R’)-MNF alters ERK signaling in melanoma cells

Cyclic AMP blocks tumor cell proliferation induced by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) ERK [33, 34]. Deregulation of ERK signaling pathway in common in melanoma partly due to the b-RAF-to-c-Raf isoform switching and concomitant inhibition of cAMP signaling [35]. Here, we investigated whether (R,R’)-MNF targets the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in melanoma cell lines by probing for MEK and ERK phosphorylation. (R,R’)-MNF reduced the constitutive levels of phosphorylated MEK and ERK, displaying U-shaped dose-response curves with a nadir at 1 nM (Fig. 6a and 6b). (R,R’)-MNF exerted comparable inhibitory effects on ERK phosphorylation in UACC-647 and M93-047 cells, while being largely inactive in UACC-903 cells (Fig. 6a). A similar dose-response relationship was observed with the β-AR agonists, (R,R’)-Fen and epinephrine, in UACC-647 cells (Fig. 6c). Pretreatment of UACC-647 cells with 50 nM ICI-118,551 blunted the decrease in phospho-ERK levels elicited by (R,R’)-MNF (Fig. 6d). Although less potent than (R,R’)-MNF, forskolin (10 µM) and NKH-477 (10 µM) also inhibited ERK phosphorylation, indicating critical involvement of cAMP in the regulation of ERK activity (Fig. 6e).

Figure 6. (R,R’)-MNF inhibits ERK activity.

(a) UACC-647, M93-047 and UACC-903 cells were serum-starved for 3 h and subsequently treated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) or a range of (R,R’)-MNF concentrations (1 fM to 1 µM) for 15 min. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylated and total forms of ERK. Top panel depicts representative blots. Values on the graph (bottom panel) represent means ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (b) Serum-starved UACC-647 cells were treated with (R,R’)-MNF (100 fM to 1 µM) for 15 min; cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted for total and phosphorylated forms of MEK1/2. Representative blots (top panel) and densitometric quantification (bottom panel) are given based on 3 independent experiments. (c) Serum-depleted UACC-647 cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) or increasing concentrations of (R,R’)-Fen or epinephrine (1 fM to 1 µM) for 15 min. The levels of total and phosphorylated ERK were determined by immunoblotting (top panel) and dose-response curves were generated (bottom panel). (d) UACC-647 cells were serum-starved for 3 h followed by the addition of ICI-118,551 (50 nM) or vehicle (water, 0.1%) for 15 min. Subsequently, cells were treated with a range of (R,R’)-MNF concentrations (1 fM to 1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%). The levels of phosphorylated and total forms of ERK1/2 were determined by ELISA. (e) UACC-647 cells were serum-starved for 3 h and treated with (R,R’)-MNF (1 nM), forskolin (10 µM), NKH-477 (10 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) for 15 min. Expression of total and phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 were assessed by ELISA. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test were used to statistically evaluate the effect of the treatments versus control cells. ***, P < 0.001. (f) Serum-depleted UACC-647 cells were treated with (R,R’)-MNF (1 nM or 1 µM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) for 0, 8, 16, 24 or 48 h. Changes in ERK phosphorylation pattern were studied by western blotting. Representative blots are depicted. Densitometric quantitation of the blots was performed and plotted (bottom panel). Statistical analysis was performed applying two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test. Asterisk symbol depicts differences in phospho-ERK in (R,R’)-MNF-treated cells versus controls for each time-point. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; n/s, not significant.

Cell stimulation with (R,R’)-MNF for short periods of time (e.g., 15 min) was more effective at blocking ERK phosphorylation when used at a concentration of 1 nM as compared to 1 µM. However, when the cells were challenged with 1 nM of (R,R’)-MNF for 48 h, the level of active, phosphorylated ERK returned to that of control cells. In contrast, incubation with 1 µM of (R,R’)-MNF maintained the repression in ERK phosphorylation for up to 48 h (Fig. 6f). These results are consistent with our observation that 1 µM of (R,R’)-MNF was effective in delaying the onset of migration and inhibiting proliferation in UACC-647 cells (see section 3.2 and 3.4).

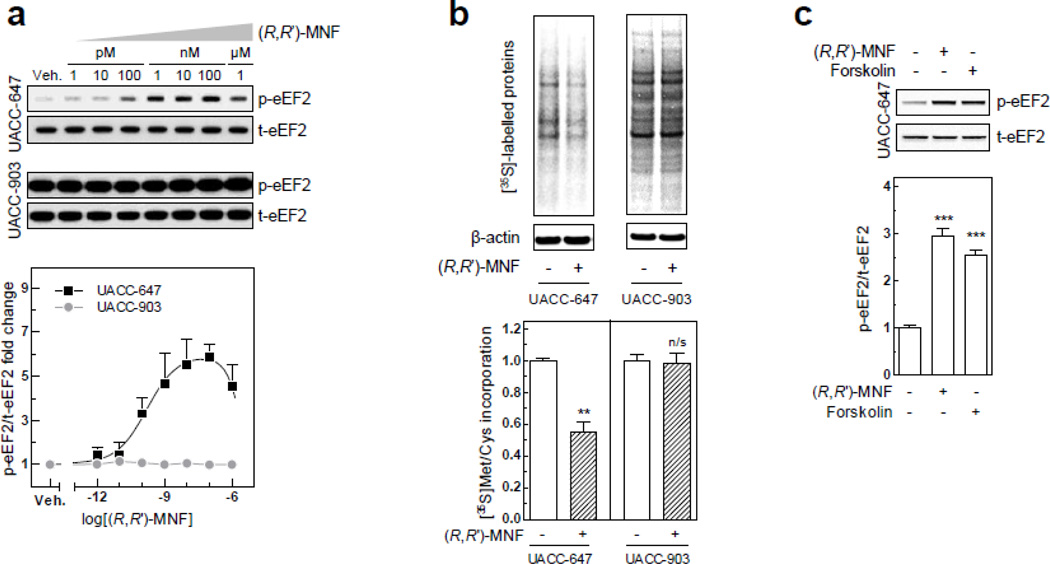

3.6 (R,R’)-MNF interferes with de novo protein synthesis

The enzyme eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) has been previously linked with β2-AR activation [36]. It is a 95-kDa protein that facilitates the translocation of the nascent protein chain from the A-site to the P-site of the ribosome, and whose activity is negatively regulated by phosphorylation on Thr56 [37]. Interestingly, a rapid and robust increase in eEF2 phosphorylation was observed in UACC-647 cells treated with (R,R’)-MNF for 15 min (Fig. 7a). The basal eEF2 phosphorylation levels were already high in UACC-903 cells and, therefore, no effect of (R,R’)-MNF was observed (Fig. 7a). Pulse-labeling experiments with [35S]-methionine were then conducted to determine whether the (R,R’)-MNF-mediated induction of eEF2 phosphorylation was translated to change in de novo protein synthesis. Significant and rapid global defect in protein biosynthesis was observed in UACC-647 cells following (R,R’)-MNF treatment, but not in UACC-903 cells (Fig 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) UACC-647 and UACC-903 cells were serum-starved for 3 h and treated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) or a range of (R,R’)-MNF concentrations (1 pM to 1 µM) for 15 min. Cell lysates were tested for the expression of phosphorylated and total forms of eEF2 by means of western blotting. Representative blots (top panel) and densitometric quantification (bottom panel) are depicted. (b) Serum-depleted UACC-647 and UACC-903 cells were treated with (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) in Met/Cys-free medium for 15 h followed by [35S] labeling for 30 min. De novo protein synthesis was assessed by autoradiography followed by the detection by immunoblotting. Effect of (R,R’)-MNF on the [35S]-Met/Cys incorporation was evaluated by Student’s t-test. **, P < 0.01; n/s, not significant. (c) UACC-647 cells were serum-starved for 3 h and then treated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%), (R,R’)-MNF (100 nM) or forskolin (10 µM) for 15 min. Cells were lysed and expression of phosphorylated and total forms of eEF2 was analyzed by western blotting. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effect of the treatments versus control cells. ***, P < 0.001.

eEF2 phosphorylation is controlled by eEF2 kinase, which, in turn, is activated in response to a number of cellular stimuli, including cAMP [37]. Treatment of UACC647 cells with forskolin (10 µM) for 15 min significantly increased eEF2 phosphorylation levels (Fig. 7c), supporting the notion that cAMP influences eEF2 phosphorylation in melanomas. These results indicate that (R,R’)-MNF decreases protein translation via a cAMP-dependent pathway, and may provide a mechanism by which it reduces expression of tumor progression-related genes (see Fig. S9).

4 Discussion

Adrenoreceptors are emerging as a new target for the management of malignant tumors. In our previous work we demonstrated that adrenergic signaling inhibits proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest in astrocytoma and glioblastoma cell lines that express the β2-AR [2]. In the present study we show that (R,R’)-MNF acts via β2-AR to impair proliferation, motility and pro-survival signaling in cultured human melanoma cells.

β2-AR is expressed in human melanocytes, although variations in magnitude of its expression were observed between individuals [4]. Conflicting results exist regarding changes in the expression level of β2-AR during tumor development. One study reported significantly higher levels of β2-AR in malignant tumors compared to benign melanocytic naevi [38] while a different group highlighted that β2-AR displayed a trend towards loss of expression in melanomas in comparison with normal melanocytes [4]. Here, we had unique opportunity to observe the effect of gene expression, as three different cell lines used throughout the study expressed various amounts of β2-AR. UACC-903 cells expressed very low levels of β2-AR, thus showing only minimal responsiveness to (R,R’)-MNF. In contrast, the M93-047 cell line was characterized by significantly higher β2-AR expression, which was accompanied by increased anti-migratory activity of (R,R’)-MNF. Finally, UACC-647, a cell line abundant in β2-AR, displayed the most profound inhibition of migration and invasion in response to (R,R’)-MNF challenge. These results are consistent with previously published reports suggesting that adrenergic signaling impairs motility of various skin cells [5, 8, 12]. In this study, however, we extend the notion of β2-AR-dependent inhibition of cellular invasiveness to human melanoma cell lines.

We have previously demonstrated that the activity and effect on cellular growth of Fen derivatives, such as (R,R’)-MNF, varies according to the properties of the target cells. In 1321N1 astrocytoma cells, both (R,R’)-MNF and (R,R’)-Fen reduced cell proliferation in a β2-AR-dependent manner [2]. However, these two compounds displayed entirely opposite activities in HepG2 cells, with (R,R’)-MNF inhibiting cellular growth and (R,R’)-Fen promoting HepG2 cell proliferation [31]. The (R,R’)-Fen-mediated increase in HepG2 cell proliferation was abolished by pretreatment with ICI-118,551, a selective β2-AR antagonist, while the anti-mitogenic activity of (R,R’)-MNF was unaffected by ICI-118,551 [31]. Further experiments established the bitopic properties of (R,R’)-MNF by demonstrating its antagonist activity towards GPR55 [3], a recently deorphanized cannabinoid-like GPCR whose activation is associated with malignancy [39]. However, the role of GPR55 in melanoma is not well established yet. In our preliminary experiments in UACC-647 cell line, we observed no effect of classical GPR55 agonists, L-α-lysophosphatidylinositol and O-1602, on cellular motility (data not shown), therefore in this model GPR55 seems to have a minimal role, if any.

In the current study, (R,R’)-MNF-evoked activities were potently inhibited by ICI-118,551 when used at nanomolar concentrations, but not by the selective β 1-AR antagonist CGP-20712A, confirming the β-AR subtype specificity for (R,R’)-MNF [1]. Positive correlation between expression level of β2-AR and the cellular response to (R,R’)-MNF was noted across the three melanoma cell lines examined, and the increase in cAMP/PKA pathway activation was consistent with β2-AR activation. Moreover, differences in potency observed in wound healing assay between the four stereoisomers of MNF were consistent with the binding pattern characteristic of chiral derivatives of Fen toward β2-AR [1, 21]. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the biological potency of (R,R’)-MNF is derived exclusively from its role as β2-AR agonist in the melanoma cell lines used in this study.

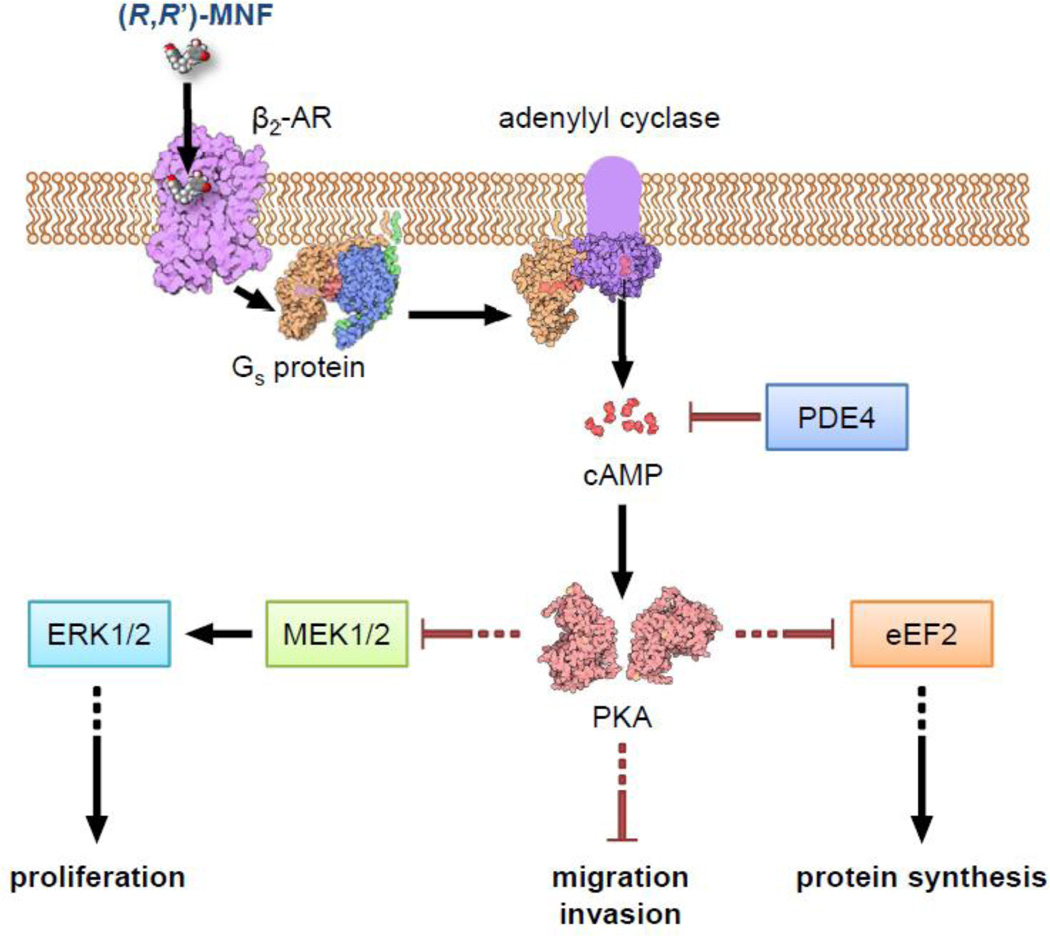

β2-AR couples predominantly to stimulatory Gs protein to induce cAMP production; however, it can also directly activate inhibitory Gi protein and β-arrestins [40]. We used a pharmacological approach to identify the signaling pathway(s) directing the anti-motility activities of (R,R’)-MNF in UACC-647 cells. Forskolin and NKH-477 are two classical activators of AC that were able to mimic (R,R’)-MNF in PET membrane migration assay. This phenomenon pointed towards a Gs/AC-dependent mode of action of (R,R’)-MNF. In UACC-647 cells, (R,R’)-MNF evoked efficient cAMP accumulation with subsequent increase in PKA activity, as evidenced by higher phosphorylation levels of PKA substrates harboring the consensus motif, Rxx[pS/pT] [41]. The fact that cell pretreatment with the PKA inhibitor H-89 successfully blocked (R,R’)-MNF-dependent activation of PKA [e.g., downstream PKA substrate phosphorylation] and abrogated the ability of (R,R’)-MNF to inhibit cell motility supports the notion of (R,R’)-MNF acting through β2-AR/Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA signal transduction pathway (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Mechanism of anti-tumorigenic activities of (R,R’)-MNF in melanoma cells.

Binding of (R,R’)-MNF to β2-AR leads to cAMP accumulation via activation of adenylyl cyclase. The resultant activation of PKA promotes a cascade of downstream signaling pathways that leads to blunted proliferation, motility and protein synthesis in melanoma cells. Phosphodiesterases can reduce cAMP-dependent signaling. This figure and the graphical abstract are adapted from illustrations obtained from ‘Molecule of the Month’ by David S. Goodsell/RCSB PDB available under CC-BY-3.0 license.

cAMP constitutes a crucial signaling molecule involved in melanocyte development and differentiation, as well as in melanin pigment production [42]. Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) is a GPCR that acts via cAMP to stimulate melanin synthesis in response to α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), its endogenous agonist [42, 43]. Jarrett and colleagues found that stimulation of cAMP via MC1R or by forskolin suppresses melanoma and facilitates genome maintenance by increasing repair rate of single-stranded DNA damage [44]. It has been also demonstrated that α-MSH acts on MC1R to inhibit migration of melanocytes in a cAMP-dependent manner [45–48]. Here, we exploited the canonical β2-AR signaling, which also relies on cAMP accumulation, to mimic MC1R activity. Ultimately, we were able to achieve significant inhibition of wound healing, decrease in migration via PET membrane and reduced invasion through matrigel matrix in different human melanoma cell lines.

The potency of cAMP signaling depends on the equilibrium between the activities of ACs and PDEs [49]. Inhibition of cAMP-specific PDEs sharply enhanced (R,R’)-MNF’s ability to reduce the invasive potential of UACC-647 cells, which indicates the importance of maintaining elevated levels of cAMP in the suppression of melanoma cell motility. These findings are supported by other studies illustrating that inhibition of various members of the PDE family reduces motility of melanoma cells [26, 27, 50]. Recently, a novel class of molecules composed of two moieties, β2-AR-agonist pharmacophore and PDE4-inhibitor pharmacophore, was synthetized [51, 52]. This type of bivalent ligands may stimulate cAMP production and prevent its degradation to dually control the migration of melanoma cells.

There are numerous targets of PKA that, when phosphorylated, can become beneficial in terms of melanoma management. For instance, filamin A can be phosphorylated by PKA on Ser2152 [53]. Phosphorylation of this residue increases the resistance of filamin A to calpain-mediated cleavage [54], thus inhibiting cell motility [16]. PKA directly phosphorylates ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) at Ser435, which, in turn, recruits nucleotide excision repair machinery to sites of DNA damage [44]. PKA-dependent phosphorylation of c-Raf at inhibitory Ser259 constitutes a point of intersection between cAMP and MAPK cascade, thus enabling negative regulation of ERK signaling through activation of β2-AR. Our future work will focus on the identification of novel β2-AR-dependent substrates of PKA and validation of their relevance for melanoma cell motility and proliferation.

eEF2 is a biomarker of melanoma cells [55], and its phosphorylation on Thr56 is associated with potent inhibition in protein translational activity [37]. The eEF2 protein was highly expressed in UACC-647 and UACC-903 melanoma cell lines, and cell treatment with (R,R’)-MNF did not reduce its expression. However, treatment of UACC-647 cells with (R,R’)-MNF led to a reduction in eEF2 activity through increased Thr56 phosphorylation, which was accompanied by downregulation of some key regulators of cellular proliferation, including cyclin A. Interestingly, our previous study revealed similar drop in cyclin A and D1 expression in response to (R,R’)-MNF both in C6 glioma cells in culture and an in vivo xenograft model [32]. Overexpression of cyclin A has been correlated with tumor thickness, tumor stage and poor prognosis in melanoma patients [56]. Therefore, inhibition of cyclin A expression may constitute an important anti-melanoma effect of (R,R’)-MNF.

Recent drug discovery programs saw the development of two mutant-selective b-RAF inhibitors, vemurafenib and dabrafenib, approved by FDA for treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma on August 2011 and March 2013, respectively [57, 58]. The use of these drugs in melanoma patients have improved greatly the therapeutic outcomes compared to chemotherapy, as measured by progression-free and overall survival [59, 60]. However, viable treatment of melanoma remains a formidable challenge as the vast majority of patients eventually develop resistance to these agents. (R,R’)-MNF negatively affects the activity of MEK and ERK, two kinases downstream of b-RAF. Thus, (R,R’)-MNF may be included as adjunct therapy to support currently available b-RAF inhibitors.

5 Conclusions

Taken together, this study rationalizes the use of β2-AR agonists for cancer management. To ensure the best clinical outcome, expression profiling should be performed on each patient, as lesions expressing high levels of β2-AR are likely to be the most responsive to (R,R’)-MNF and other β2-AR activators. Data gathered in this study identified (R,R’)-MNF as a potent inhibitor of proliferation and motility of melanoma cells in vitro, and that in these cells, the effect of (R,R’)-MNF is dependent upon cAMP accumulation and downstream inhibition of cell migration, proliferation and protein synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

➢

β2 adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) is differentially expressed in melanoma cell lines.

-

➢

(R,R‘)-4’-methoxy-1-naphthylfenoterol [(R,R ’)-MNF] activates β2-AR in melanoma.

-

➢

(R,R’)-MNF inhibits migration, invasion, and growth of melanoma cells via β2-AR.

-

➢

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) is crucial for anti-tumorigenic activities of β2-AR.

-

➢

β2-AR agonists can be used to restore cAMP signaling in melanomas.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by funds from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging/NIH, NIA/NIH (contract N01-AG-3-1009) and the Foundation for Polish Science (TEAM 2009-4/5 programme).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- α-MSH

α-melanocyte stimulating hormone

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AR

adrenergic receptor

- ATR

ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 -related protein

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CI

cell index

- CIM

cell invasion and migration

- eEF2

eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- Fen

fenoterol

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MC1R

melanocortin 1 receptor

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MNF

4’-methoxy-1 –naphthylfenoterol

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PET

polyethylene terephthalate

- PKA

protein kinase A

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest other than the fact that IW Wainer, M Bernier, RK Paul, LR Toll and LA Jimenez are listed as co-inventors on a patent application for the use of fenoterol and other fenoterol derivatives [including (R,R’)-MNF] in the treatment of glioblastomas and astrocytomas. Wainer, Bernier and Paul have assigned their rights in the patent to the US government, but will receive a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government.

Contributions

Participated in research design: Wnorowski, Paul, Toll, Jozwiak, Bernier, Wainer

Conducted experiments: Wnorowski, Sadowska, Paul, Singh, Boguszewska-Czubara, Jimenez, Abdelmohsen

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Wnorowski, Bernier

Supervised the work: Toll, Jozwiak, Bernier and Wainer

Initiated the research: Wainer, Bernier

Contributor Information

Artur Wnorowski, Email: artur.wnorowski@gmail.com.

Mariola Sadowska, Email: mariolas349@gmail.com.

Rajib K. Paul, Email: rajibkpaul@gmail.com.

Nagendra S. Singh, Email: nagendra.singh@nih.gov.

Anna Boguszewska-Czubara, Email: anna.boguszewska-czubara@am.lublin.pl.

Lucita Jimenez, Email: lucitaj.imenez@sri.com.

Kotb Abdelmohsen, Email: abdelmohsenk@grc.nia.nih.gov.

Lawrence Toll, Email: ltoll@tpims.org.

Krzysztof Jozwiak, Email: krzysztofjozwiak@umlub.pl.

Michel Bernier, Email: bernierm@mail.nih.gov.

Irving W. Wainer, Email: iwainer@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Jozwiak K, Woo AY, Tanga MJ, Toll L, Jimenez L, Kozocas JA, Plazinska A, Xiao RP, Wainer IW. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:728–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toll L, Jimenez L, Waleh N, Jozwiak K, Woo AY, Xiao RP, Bernier M, Wainer IW. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:524–532. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul RK, Wnorowski A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Nayak SK, Pajak K, Moaddel R, Indig FE, Bernier M, Wainer IW. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Zhang G, Pittelkow MR, Ramoni M, Tsao H. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2490–2506. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Leary AP, Fox JM, Pullar CE. J Cell Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jcp.24716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pullar CE, Isseroff RR. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:405–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duell EA. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullar CE, Le Provost GS, O’Leary AP, Evans SE, Baier BS, Isseroff RR. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2076–2084. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arwert EN, Hoste E, Watt FM. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:170–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedberg IM, Tomic-Canic M, Komine M, Blumenberg M. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steenhuis P, Huntley RE, Gurenko Z, Yin L, Dale BA, Fazel N, Isseroff RR. J Dent Res. 2011;90:186–192. doi: 10.1177/0022034510388034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pullar CE, Grahn JC, Liu W, Isseroff RR. FASEB J. 2006;20:76–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4188com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Hoffman BB, Isseroff RR. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1261–1268. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pullar CE, Chen J, Isseroff RR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22555–22562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGettigan S. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5:211–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connell MP, Fiori JL, Baugher KM, Indig FE, French AD, Camilli TC, Frank BP, Earley R, Hoek KS, Hasskamp JH, Elias EG, Taub DD, Bernier M, Weeraratna AT. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1782–1789. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bittner M, Meltzer P, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Seftor E, Hendrix M, Radmacher M, Simon R, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, Sampas N, Dougherty E, Wang E, Marincola F, Gooden C, Lueders J, Glatfelter A, Pollock P, Carpten J, Gillanders E, Leja D, Dietrich K, Beaudry C, Berens M, Alberts D, Sondak V. Nature. 2000;406:536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jozwiak K, Khalid C, Tanga MJ, Berzetei-Gurske I, Jimenez L, Kozocas JA, Woo A, Zhu W, Xiao RP, Abernethy DR, Wainer IW. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2903–2915. doi: 10.1021/jm070030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geback T, Schulz MM, Koumoutsakos P, Detmar M. Biotechniques. 2009;46:265–274. doi: 10.2144/000113083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plazinska A, Pajak K, Rutkowska E, Jimenez L, Kozocas J, Koolpe G, Tanga M, Toll L, Wainer IW, Jozwiak K. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connell MP, Fiori JL, Xu M, Carter AD, Frank BP, Camilli TC, French AD, Dissanayake SK, Indig FE, Bernier M, Taub DD, Hewitt SM, Weeraratna AT. Oncogene. 2010;29:34–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiori JL, Zhu TN, O’Connell MP, Hoek KS, Indig FE, Frank BP, Morris C, Kole S, Hasskamp J, Elias G, Weeraratna AT, Bernier M. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2551–2560. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker JG. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:317–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson GP. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006;31:119–130. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:31:2:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiramoto K, Murata T, Shimizu K, Morita H, Inui M, Manganiello VC, Tagawa T, Arai N. Cell Signal. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe Y, Murata T, Shimizu K, Morita H, Inui M, Tagawa T. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:205–210. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquette A, Andre J, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Dumaz N. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:584–591. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumaz N, Marais R. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29819–29823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown KM, Day JP, Huston E, Zimmermann B, Hampel K, Christian F, Romano D, Terhzaz S, Lee LC, Willis MJ, Morton DB, Beavo JA, Shimizu-Albergine M, Davies SA, Kolch W, Houslay MD, Baillie GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1533–E1542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303004110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul RK, Ramamoorthy A, Scheers J, Wersto RP, Toll L, Jimenez L, Bernier M, Wainer IW. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:157–166. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.195206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernier M, Paul RK, Dossou KS, Wnorowski A, Ramamoorthy A, Paris A, Moaddel R, Cloix JF, Wainer IW. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2013;1:e00010. doi: 10.1002/prp2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook SJ, McCormick F. Science. 1993;262:1069–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.7694367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, Dent P, Jelinek T, Wolfman A, Weber MJ, Sturgill TW. Science. 1993;262:1065–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.7694366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumaz N, Hayward R, Martin J, Ogilvie L, Hedley D, Curtin JA, Bastian BC, Springer C, Marais R. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9483–9491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLeod LE, Wang L, Proud CG. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:225–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaul G, Pattan G, Rafeequi T. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29:227–234. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moretti S, Massi D, Farini V, Baroni G, Parri M, Innocenti S, Cecchi R, Chiarugi P. Lab Invest. 2013;93:279–290. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andradas C, Caffarel MM, Perez-Gomez E, Salazar M, Lorente M, Velasco G, Guzman M, Sanchez C. Oncogene. 2011;30:245–252. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baillie GS, Sood A, McPhee I, Gall I, Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Houslay MD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:940–945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262787199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Kemp BE, Graves DJ, Benjamini E, Krebs EG. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4888–4894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Wortsman J. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155–1228. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newton RA, Smit SE, Barnes CC, Pedley J, Parsons PG, Sturm RA. Peptides. 2005;26:1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarrett SG, Horrell EM, Christian PA, Vanover JC, Boulanger MC, Zou Y, D’Orazio JA. Mol Cell. 2014;54:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Murata J, Ayukawa K, Ogasawara M, Fujii H, Saiki I. Invasion Metastasis. 1997;17:82–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu GS, Liu LF, Lin CJ, Tseng JC, Chuang MJ, Lam HC, Lee JK, Yang LC, Chan JH, Howng SL, Tai MH. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:440–451. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kameyama K, Vieira WD, Tsukamoto K, Law LW, Hearing VJ. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:1151–1158. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murata J, Ayukawa K, Ogasawara M, Watanabe H, Saiki I. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:889–895. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<889::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sassone-Corsi P. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abusnina A, Keravis T, Zhou Q, Justiniano H, Lobstein A, Lugnier C. Thromb Haemost. 2014:113. doi: 10.1160/TH14-05-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shan WJ, Huang L, Zhou Q, Jiang HL, Luo ZH, Lai KF, Li XS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tannheimer SL, Sorensen EA, Cui ZH, Kim M, Patel L, Baker WR, Phillips GB, Wright CD, Salmon M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349:85–93. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.210997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jay D, Garcia EJ, Lara JE, Medina MA, de la Luz Ibarra M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;377:80–84. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peverelli E, Giardino E, Vitali E, Treppiedi D, Lania AG, Mantovani G. Horm Metab Res. 2014 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1384520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki A, Iizuka A, Komiyama M, Takikawa M, Kume A, Tai S, Ohshita C, Kurusu A, Nakamura Y, Yamamoto A, Yamazaki N, Yoshikawa S, Kiyohara Y, Akiyama Y. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2010;7:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yam CH, Fung TK, Poon RY. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1317–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim G, McKee AE, Ning YM, Hazarika M, Theoret M, Johnson JR, Xu QC, Tang S, Sridhara R, Jiang X, He K, Roscoe D, McGuinn WD, Helms WS, Russell AM, Pope Miksinski S, Fourie Zirkelbach J, Earp J, Liu Q, Ibrahim A, Justice R, Pazdur R. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ballantyne AD, Garnock-Jones KP. Drugs. 2013;73:1367–1376. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M, Hogg D, Lorigan P, Lebbe C, Jouary T, Schadendorf D, Ribas A, O’Day SJ, Sosman JA, Kirkwood JM, Eggermont AM, Dreno B, Nolop K, Li J, Nelson B, Hou J, Lee RJ, Flaherty KT, McArthur GA. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, Rutkowski P, Blank CU, Miller WH, Jr, Kaempgen E, Martin-Algarra S, Karaszewska B, Mauch C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Martin AM, Swann S, Haney P, Mirakhur B, Guckert ME, Goodman V, Chapman PB. Lancet. 2012;380:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.