Abstract

Background

IgG4-associated autoimmune diseases are systemic diseases affecting multiple organs of the body. Autoimmune pancreatitis, with a prevalence of 2.2 per 100 000 people, is one such disease. Because these multi-organ diseases present in highly variable ways, they were long thought just to affect individual organ systems. This only underscores the importance of familiarity with these diseases for routine clinical practice.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, and on the published conclusions of international consensus conferences.

Results

The current scientific understanding of this group of diseases is based largely on case reports and small case series; there have not been any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to date. Any organ system can be affected, including (for example) the biliary pathways, salivary glands, kidneys, lymph nodes, thyroid gland, and blood vessels. Macroscopically, these diseases cause diffuse organ swelling and the formation of pseudotumorous masses. Histopathologically, they are characterized by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with IgG4-positive plasma cells, which leads via an autoimmune mechanism to the typical histologic findings—storiform fibrosis (“storiform” = whorled, like a straw mat) and obliterative, i.e., vessel-occluding, phlebitis. A mixed Th1 and Th2 immune response seems to play an important role in pathogenesis, while the role of IgG4 antibodies, which are not pathogenic in themselves, is still unclear. Glucocorticoid treatment leads to remission in 98% of cases and is usually continued for 12 months as maintenance therapy. Most patients undergo remission even if untreated. Steroid-resistant disease can be treated with immune modulators.

Conclusion

IgG4-associated autoimmune diseases are becoming more common, but adequate, systematically obtained data are now available only from certain Asian countries. Interdisciplinary collaboration is a prerequisite to proper diagnosis and treatment. Treatment algorithms and RCTs are needed to point the way to organ-specific treatment in the future.

Probably the first description of an IgG4-related disease of the salivary gland was by Mikulicz-Radecki (e1). Later publications identified the mononuclear infiltrate in what became known as Mikulicz disease as IgG4-positive plasma cells (e2). An autoimmune cause of chronic sclerosing pancreatitis was suspected as early as 1961 (e3).

The first evidence of an association between raised serum concentrations of IgG4 and the occurrence of a steroid-sensitive sclerosing pancreatitis was shown in 2001 (e4). In autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), two forms of disease are distinguished: type 1 and type 2 AIP, only the former of which is an IgG4-related disease. In patients with type 1 AIP, additional extrapancreatic manifestations were an early finding (1).

In 2003, a connection between various apparently discrete diseases and the occurrence of raised IgG4 levels and a pathognomonic histological appearance were described (1, 2, e4– e6). Any organ system—bile ducts, for example, or salivary glands, kidneys, lymph nodes, thyroid, or blood vessels—can be affected (Table 1). The term “IgG4-related disease” was coined in 2010 at a Japanese consensus conference (3, e7).

Table 1. IgG4-related diseases: specific names, symptoms, prevalence.

| Organ system | Specific name(s) | Symptoms | Prevalence data | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas | AIP types 1 and 2 | Epigastric pain, weight loss, cholestasis | Prevalence 2.2 : 100000 in a nationwide survey at two Japanese university hospitals | (4, 7, e11) |

| Liver | IgG4-related hepatitis | Icterus, hepatic mass | Only small case series | (e11, e40) |

| Biliary tract | IgG4-related cholangiopathy | Cholestasis, pruritus | In 80% of AIP patients the biliary tract is involved | (19, 22, e11) |

| Salivary and lacrimal glands | Mikulicz syndrome, Küttner’s tumor | Usually bilateral swelling Warning: Must be distinguished from Sjögren syndrome, in which the submandibular gland is usually spared | Approx. 2% in a retrospective study of 129 patients with obstructive sialadenitis | (e11, e32) |

| Ophthalmologic manifestation | Chronic sclerosing dacryoadenitis, eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis, orbital pseudotumor, idiopathic orbital inflammation | Lacrimal gland swelling with secondary proptosis | In 23% of 113 patients with IgG4- related disease, ophthalmologic manifestation was noted in a retrospective database | (e11, e41) |

| Thyroid | Riedel’s thyroiditis (=IgG4-positive, fibrosing Hashimoto thyroiditis) | Hypothyroidism, neck pain, dyspnea, dysphagia, dysphonia | 12 of 53 Hashimoto patients were IgG4-positive in a retrospective analysis | (33, e11) |

| Kidneys | Tubulointerstitial nephritis | Proteinuria, hematuria, increased creatinine up to the point of chronic or acute renal failure, hypocomplementemia | 13 of 114 patients with IgG4- associated disease had retroperitoneal involvement, including Ormond’s disease | (34, 35, e11) |

| Blood vessels | IgG4-related aortitis, periaortitis, or IgG4-related abdominal aortic aneurysm | Angina pectoris, chest pain, dyspnea | 13 cases of IgG4-related aortic aneurysm in a series of 252 operated cases | (e11, e42) |

| Retroperitoneal space | Retroperitoneal fibrosis (Ormond’s disease) | Flank pain, leg edema, hydronephrosis | Estimated prevalence of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is 1: 200000 (no data on percentage of IgG4-positive cases) | (35, 36, e11) |

| Mesentery | Sclerosing mesenteritis | In the early stage, nonspecific abdominal pain, meteorism | In 0.6% of 7000 abdominal CT studies the corresponding radiological criteria for scleorsing mesenteritis were found | (e11, e43) |

| Intracranial manifestation | IgG4-related hypophysitis, IgG4-related pachymeningitis | Headache corresponding to the involved hormonal axis, spinal compression, radiculopathies | In 4% of 170 patients with hypopituitarism and/or diabetes insipidus, an IgG4-related disease was found | (e11, e44) |

| Genitalia | IgG4-related prostatitis, IgG4-related orchitis | Pain, pollakisuria, BPH-typical, improves after steroid treatment | 9 cases of IgG4-related prostatitis in a cohort of 117 men with diagnosed AIP or IgG4-related cholangiopathy | (e11, e45) |

| Lung | IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor, interstitial pneumonia, or pleuritis | Dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, pleural effusion | Only small case series | (37, e11) |

| Skin | 7 different subtypes | See further literature (38, e11) | Only small case series | (38, e11) |

CT, computed tomography; AIP, autoimmune pancreatitis; BPH, benign prostate hyperplasia

Epidemiology

Only a few epidemiological studies have been carried out into IgG4-related diseases. Japanese studies show a prevalence of around 100 cases per 1 million inhabitants, with an annual incidence of around 1 in 100 000 persons (3, 4). A study carried out at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota (USA) reported that 11% of 245 patients who underwent pancreatectomy for benign disease had autoimmune pancreatitis (e8). A recent study from the German-speaking countries investigated 72 AIP patients, 40 with type 1 and 32 with type 2 AIP. In 15 of the type 1 AIP patients, the diagnosis was made surgically. All 32 patients with type 2 AIP underwent surgery (5). Overall, the incidence and prevalence of IgG4-related disease are probably underestimated. However, as awareness of IgG4-related disease has increased over the past 10 years, it is being diagnosed more often (Table 1) (3, 6).

IgG4-related disease occurs predominantly in men (in the case of AIP, for example, 3.5 times more often in men than in women). However, there is a certain variability, depending on the organ or organ system affected: in the head–neck region, for example, IgG4-related disease occurs in men and women with almost equal frequency (Table 1) (6, 7).

Most of the data about genetic predisposition to IgG4-related disease originates in Japanese AIP patient groups and needs to be validated in non-Asiatic countries (e9).

Pathophysiology

Of all IgG subclasses in peripheral blood, IgG4 antibodies have the lowest concentration (0.35 to 0.51 mg/mL) (e9). They are formed in response to environmental or nutritional antigens, but only after long-term exposure. IgG4 antibodies induce only a low level of phagocytosis, antibody-mediated cytotoxicity, and complement activation (6, e10). The exact pathophysiology is insufficiently understood. Molecular mimicry may play a role, in the form of cross-reactivity between bacterial peptide sequences (e.g., ubiquitin ligase from Helicobacter pylori [e11]) with the body’s own/autologous proteins, triggering the formation of autoantibodies (e12, e13). These findings led to the proposal of a two-stage model with initial molecular mimicry and induction of a Th1-response. Persistence of the triggering pathogens could then lead to a Th2- and Treg-mediated immune response and to IgG4-related disease (8). The cytokines released during this process (e.g., IL-4, TGF-β1) are probably responsible for the organ fibrosis typically found in IgG4-related disease (e14).

Diagnosis

So far, a variety of organ-specific diagnostic systems have been developed, largely using the same parameters (9). The Japanese study group for the diagnostic evaluation of IgG4-related disease proposes three main diagnostic criteria (10):

Characteristic organ swelling or space-occupying mass in the clinical examination or corresponding axial imaging

Raised serum IgG4 concentration

Characteristic histology.

The organ swelling can be diffuse or focally limited. When it occurs in paired organs—e.g., the salivary glands— symmetrical swelling increases the likelihood of the diagnosis (3). For a description of the appearance of the organ swelling on various imaging techniques, readers are referred to published review articles (e15). The final diagnostic gold standard remains histopathological confirmation (10) (Figure 1, (eFigure 1).

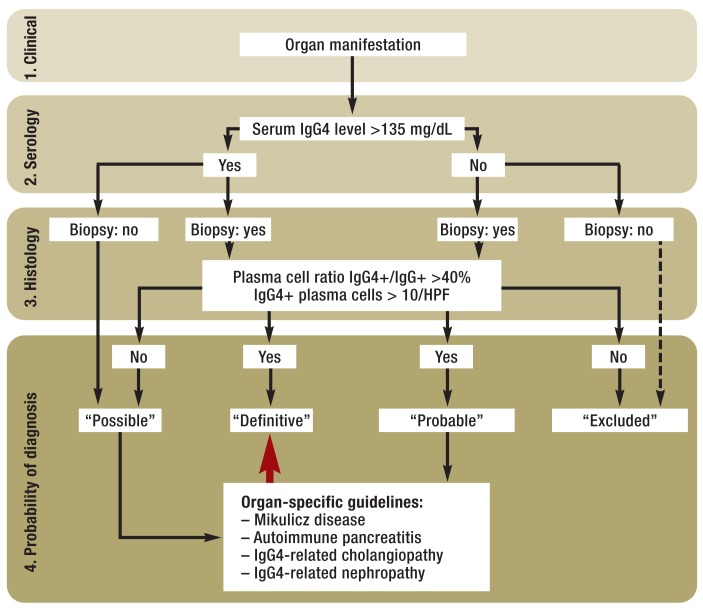

Figure 1.

Diagnostic algorithm corresponding to the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japanese study group for IgG4-related disease (modified from Okazaki et al. [10])

IgG4+: IgG4-positive

HPF: high power field

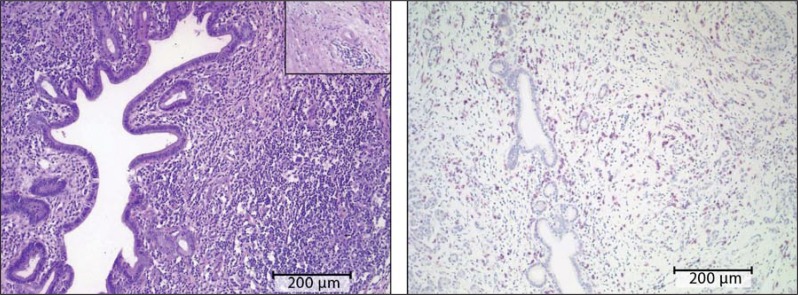

eFigure 1.

Histopathological findings in type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis: a) hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining. Inset: vascular involvement in the inflammatory process. b) Immunohistochemical evidence of IgG4-positive plasma cells

Typically, a triad of histological features is found (eFigure 1a and b) (e6):

Dense lymphoplasmacellular inflammatory infiltrate, consisting of IgG4-positive plasma cells among others

Marked fibrosis with a storiform pattern

Vascular inflammation with phlebitis with or without obliteration of the lumen.

In most cases, increased eosinophilic granulocytes are seen (e16). Except in type 2 AIP, epithelioid cell granulomas and prominent neutrophilic infiltrates are atypical (Table 2) (e11). A small number of IgG4-positive cells are found in physiological conditions and also in other diseases in various tissues, and for this reason, the published literature recommends determining the ratios of IgG4-positive to IgG-positive cells. If the proportion of IgG4-positive cells is more than 40%, the diagnosis of IgG4-related (auto)immune disease may be regarded as confirmed. In (small) biopsies, >10 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high power field (HPF) should be visible, although the threshold values described in the literature vary widely. It is rare that a diagnosis can be confirmed on the basis of a cytological sample alone. If AIP is suspected, gastric and/or papillary biopsy may help to provide indicators for the diagnosis, since in some cases of AIP gastric or duodenal involvement has been described (e11). IgG4-positive cells can also be present in the intratumoral inflammatory infiltrate of malignant tumors (e17). This finding underlines the importance of the classical histological criteria for diagnosing IgG4-related disease. Details of diagnostic serological analysis are shown separately (Box) (3, 10– 12, e11, e18, e19).

Table 2. Comparison of type 1 and type 2 AIP.

| Histopathological feature | Type 1—sclerosing (lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, LPSP) | Type 2—florid, duct-centric (idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis, IDCP) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared criteria | Periductal lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate | Present | Present |

| Inflammatory cell-rich stroma | Present | Present | |

| Diagnosis of type 1 AIP | Storiform fibrosis | Very prominent | Rare |

| Obliterating phlebitis | Present | Rare | |

| Prominent lymph follicle | Present | Rare | |

| IgG4-positive plasma cells | Increased (>10 per high power field) | Less noticeable | |

| Diagnosis of type 2 AIP | Granulocytic epithelial lesions (GELs) | Absent | Present |

| Neutrophilic periacinar infiltrate | Absent | Very frequent | |

| Abscesses | Absent | Present | |

| Acinus/lobe | Normal | Atrophic | |

| Ductal epithelium | Intact | Inflamed/regenerative | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis (14–39%) IgG4-related cholangitis (IAC) (12–47%) IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis and renal parenchyma lesions (35%) Swelling of hilar lymph nodes of the lung (8–13%) Retroperitoneal fibrosis (n. d.) Chronic thyroiditis (n. d.) Prostatitis (n. d.) Inflammatory bowel disease (0.1–6%) | Inflammatory bowel disease (16%) | |

AIP, autoimmune pancreatitis; n. d., no data

Box. Serology.

A serum IgG4 concentration >135 mg/dL has been defined as the threshold value for diagnosis.

A serum IgG4:IgG ratio >8% has been defined as the threshold value for diagnosis.

Recent research recommends an IgG4:IgG1 ratio of >0.24 as a possible parameter for distinguishing serologically between primary sclerosing cholangitis (PCS) and IgG4-associated cholangiopathy.

About 70% to 80% of patients with type 1 AIP had raised IgG4 concentrations. Studies on autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) showed that in some patients IgG4 levels did not return to normal even during clinical remission.

The prognostic significance of the rise in IgG4 remains unclear.

Cases do occur where a typical histology is shown but IgG4 levels are normal.

Polyclonal gammaglobulinemia, increased IgE, or complement consumption can occur in IgG4-related disease but their sensitivity is low.

Separate guidelines have been developed for type 1 AIP, Mikulicz disease, and IgG4-dependent renal disease.

The Japanese study group propose that a definitive diagnosis of IgG4-related disease should only be given in the presence of all three criteria (clinical features, histology, raised serum IgG4). If only clinical features and a histological result consistent with IgG4-related disease are present, the diagnosis is “probable.” If only the typical clinical features and a serum IgG4 concentration above the threshold value are present, the diagnosis is “possible” (10). The sensitivity of the three above-mentioned criteria is satisfactory for a “definitive” or “probable” diagnosis in Mikulicz disease and in IgG4-related kidney disease; only AIP is inadequately represented by these criteria (e20). A possible diagnostic algorithm for IgG4-related disease is given in Figure 1.

Clinical manifestations

Autoimmune pancreatitis type 1

Type 1 AIP represents the pancreatic manifestations of systemic sclerosing IgG4-related disease (Tables 1 and 2). Diagnosis on the basis of a combination of the criteria shown in Figure 1 is possible in only about 70% of patients (e21), and for this reason, specific criteria have been laid down for type 1 AIP (13). In addition to the histological findings, the following criteria are taken into account:

Imaging findings in the parenchyma and biliary system

Serology results

Extrapancreatic manifestations

Response to steroids.

Another possible diagnostic system is the HISORt score, which basically uses the same criteria weighted differently (9). Sensitivity and specificity are 92% and 97% respectively (e22). Despite this, AIP is found in around 2.6% of patients undergoing surgery for suspected cancer (14). According to one small prospective study, it is possible to distinguish reliably between cancer and AIP by trialing steroid therapy for 2 weeks (15). However, it has to be borne in mind that this entails the risk of masking the diagnosis in a patient with malignant lymphoma (10).

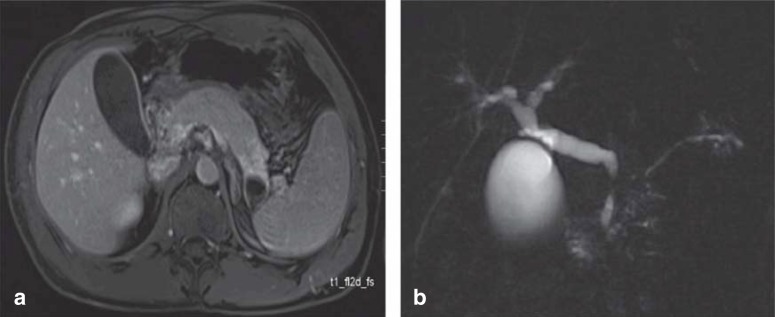

In the acute stage, in 40% of patients transabdominal or endoscopic ultrasonography shows the pancreas as diffusely enlarged (“sausage-shaped pancreas”) (MRI in Figure 2a, the same on CT), with reduced echogenicity and a very narrow pancreatic duct. In 60%, a focus is found (up to 50 mm) (16, e21). In such a case, it can be difficult to distinguish between AIP and pancreatic cancer (13, e23). The pancreatic duct may be stenotic for a long stretch or in segments. Prestenotic dilatations are typically absent (Figure 2b). Where AIP is suspected, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) can be used as a primary diagnostic investigation (e24). Four core criteria have been developed for the diagnosis of AIP by ERP (17):

Figure 2.

Imaging in autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP): a) MRI shows a sausage-shaped, swollen pancreas with the main finding in the area of the body and tail. b) MRCP shows the AIP-typical variations in the caliber of the pancreatic duct without prestenotic dilatation and with a classic double duct sign, i.e., localized stenosis in both the bile duct and the pancreatic duct. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CHD, common hepatic duct; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Stricture or narrowing of the pancreatic duct over more than a third of its course

No duct dilatation >5 mm proximal to the stricture

Multiple strictures or narrowings

Contrast enhancement of side branches leaving the stenosed main duct at right angles.

The greatest accuracy is found for the combination “duct dilatation >5 mm proximal to the stricture” and “multiple strictures/narrowings” (sensitivity 89%, specificity 91%) (17). ERP/ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) cannot exclude malignant disease, since for example the classic double duct sign—that is, localized stenosis of both the bile duct and the pancreatic main duct—is present in up to 67% of patients with AIP (15, e25). Enlarged lymph nodes are seen in around 50% of patients. Pancreatic stones and pseudocysts are found only in advanced stage disease (e26). Histological confirmation is usually by means of endoscopic ultrasound. Raised serum concentrations of IgG4 are found in 63% of patients with type 1 AIP with classic histology and only 23% of patients with type 2 AIP, although marked regional variation exists (16). Type 2 AIP is a separate entity with a different pathophysiology, lower recurrence rates, and a close association with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Both types respond excellently to steroids (18). Type 2 AIP is more extensively discussed by Beyer et al. (e27) and is compared to type 1 AIP in Table 2.

IgG4-related cholangiopathy

The differential diagnosis of IgG4-related cholangiopathy must include all primary and secondary forms of sclerosing cholangitis and pancreatobiliary tumors. In around 50% to 80% of cases there is an association with type 1 AIP (19). Patients with IgG4-related cholangiopathy and AIP are usually over 60 years old and often male (men are affected eight times as often as women) (20, e28). As would be expected with this sex distribution, in several independent IAC cohorts there was a disproportionately high number of workers who had had high exposure to solvents, industrial dust and lubricants, and pesticides (21), and a significantly higher proportion of IgG4-positive B-cell receptor clones (e29).

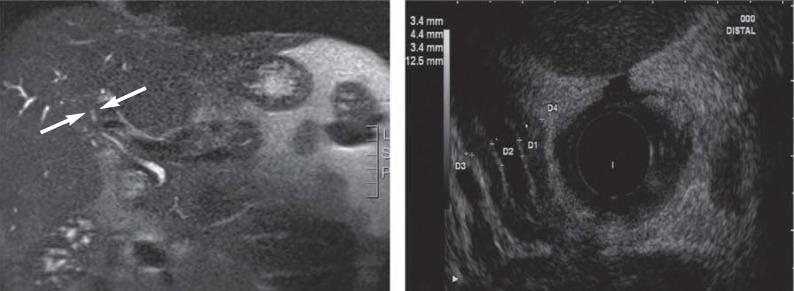

Four types can be distinguished cholangiographically (eFigure 2a):

eFigure 2.

Imaging in IgG4-related cholangitis (IAC): a) MR image of a stenosis close to the hilum with evidence of an inflammatory pseudotumor (arrows). b) Endoscopic ultrasound shows circular wall thickening with distal common hepatic duct stenosis

Type 1: Isolated distal stenosis of the common hepatic duct (CHD)

Type 2: Diffuse stenoses

Type 3: Hilar and distal CHD stenosis

Type 4: Isolated hilar CHD stenosis.

Imaging shows symmetrical, circular wall thickening (endoscopic ultrasound appearance shown in eFigure 2b), which can also affect nonstenosed regions of the bile duct (22). Criteria for IgG4-related cholangiopathy are a pathological cholangiogram (types 1–4), raised serum IgG4 concentration, coexisting AIP, sialadenitis, or retroperitoneal fibrosis, and typical histological findings (e30). Sensitivities around 50% with specificities above 90% were found for endoscopic biopsy of the ampulla of Vater and distal part of the bile duct (23). However, false positive histological results for IgG4-positive cells were noted in 12% of cases, making it harder to distinguish IgG4-related cholangiopathy from sclerosing cholangitis or cholangiocarcinoma. For this reason, diagnosis is often only possible on the basis of assessing the response to a trial of steroid therapy (15, 19, 23). Diagnosis is usually according to the HISORt criteria (19).

Head and neck manifestations

IgG4-related diseases in the head–neck area are (24, e31):

Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis

Riedel thyroiditis

Chronic sclerosing dacryoadenitis

Many orbital pseudotumors

Eosinophilic angiocentric and cervical fibrosis.

Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis of the submandibular gland (Küttner’s tumor) is a typical manifestation, although the relative frequency measured against all cases of sialadenitis—especially those obstructively triggered—is low (about 2% in a retrospective study of 129 cases [e32]). An important clinical feature is a notably rough, movable, indolent space-occupying mass located caudal to the lower jaw, and occasionally bilateral (25, e31).

The rare Riedel thyroiditis, an invasive sclerosing inflammation of the thyroid, is a special form of IgG4-related disease. The hard struma or goiter, also known as “cast iron struma”, typically does not move with swallowing, and can constrict the airway by invasive growth until it causes laryngeal paralysis, thus mimicking a malignant tumor. The fibrosing subform Hashimoto thyroiditis is now also classed as an IgG4-related disease (24, e33). Orbital involvement, through involvement of the lacrimal glands and the periorbital tissue, can lead to swelling of the eyelids, proptosis, double vision, and other alterations of vision.

The orbit can also be affected by so-called eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis, but here the sinus tract will also be involved, giving rise to a similarity with Wegener disease. In addition to the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis, episodes of epistaxis have been reported (e16, e34).

In the neck region, in addition to cervical fibrosis with diffuse infiltrative soft tissue processes, an asymptomatic lymphadenopathy (five histological subtypes) has been described, which may be accompanied by synchronous or metachronous extranodal lesions (25, e31, e33). For histological confirmation and differential diagnosis of the lesions, an (open) biopsy or tumor resection (Küttner’s tumor) is usually necessary (24, e1, e6).

IgG4-related kidney disease

The most frequent renal manifestation of IgG4-related disease is tubulointerstitial nephritis, which is associated with either chronic renal insufficiency or acute renal failure (e11). Typically, non-nephrotic proteinuria, hematuria, and hypocomplementemia are found (e35). In addition, renal space-occupying masses are found, often multiple and bilateral (26). Renal biopsy shows, in addition to the typical IgG4-positive plasma cells, extensive interstitial fibrosis and immune complex deposits along the tubular basement membrane (26). Glomerular involvement in the form of membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) may occur (e36). Immunohistochemically, the form of MGN, unlike the classical form, is negative for the phospholipase A2 receptor (e36). Although the disease typically responds well to steroid treatment, if delayed diagnosis has led to renal fibrosis or atrophy, chronic renal insufficiency may result (e11, e35).

Treatment

Recommendations for the treatment of IgG4-related disease are limited to retrospective analyses or small prospective, one-armed studies. At present, no data from RCTs exist. All IgG4-positive syndromes respond very well to steroids (6), with 98% of cases going into remission. Most treatment experience has been with autoimmune pancreatitis (18, 27). Type 1 AIP does not always require treatment. Remission occurs in 74% of patients even without treatment (28). International guidelines recommend steroid therapy for AIP in patients with symptoms such as clinically significant cholestasis, pancreatogenic pain, and weight loss (29). Similar recommendations apply for all other IgG4-positive diseases (6).

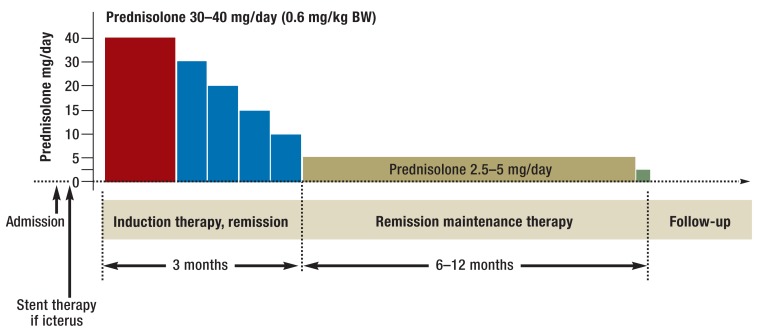

Disease recurrence is seen in 42% of patients who have not received steroid therapy and only 24% of those who have (28). For this reason, 12-month maintenance therapy is favored in Asia (Figure 3). The possible negative effects of long-term steroid therapy need to be weighed against the recurrence rate (5.1% with maintenance treatment versus 22.7% without) (30). Recurrent flare-ups of an IgG4-positive disease lead to irreversible damage to the organ concerned; in AIP this means a similar course to chronic pancreatitis with calcifications in up to 54% of cases (31, e37). In a cohort at the Mayo Clinic, after steroid therapy for type 1 AIP, recurrence was seen in 43% of cases (32). The recurrence rate was highest (67%) in the group in which steroid therapy was stopped abruptly; by contrast, slow step-wise tapering off of steroid therapy and steroid maintenance therapy were both associated with lower recurrence rates (18% each) (32). These data support a 12-month maintenance regime (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scheme for treatment of IgG4-related disease according to the Japanese guidelines. The recommendations relate mainly to autoimmune pancreatitis, but can probably be applied to other forms of IgG4-related disease.

BW, body weight

Independent factors that promote recurrence are (31, e38): male sex, young age at onset, and low IgG4 concentration in disease shown on imaging to be advanced. A low steroid dosage to treat the first episode of an IgG4-mediated disease also appears to be associated with a higher rate of recurrence (e38). Combined therapy with an alternative immunosuppressant and a steroid does not lead to a lower recurrence rate (18). However, steroid-free therapy with an alternative immunosuppressant (e.g., azathioprine) to maintain remission after a recurrence is no less effective than a new course of steroid therapy (18). As to the efficacy of non-steroid-based therapies to induce remission, only uncontrolled case reports exist. The CD20 antibody rituximab has been reported as successfully used in AIP, though only in very small numbers of patients (18, e39). Similar data exist for IgG4-positive cholangiopathy and hepatopathy, and for Mikulicz disease (e39).

Key Messages.

The term “IgG4-related disease” has become established in the past few years as a generic term for a group of diseases in numerous organ systems that previously were not regarded as connected with each other. It refers to fibrotic inflammatory disease manifestations that can affect almost any organ. Because the disease can often have a pseudotumorous appearance, it is essential for the differential diagnosis to include malignancy.

Current lack of understanding of IgG4-related disease has led to the proposal of a two-stage model involving molecular mimicry and induction of a Th1 immune response in the first stage. Persistence of the triggering pathogens could then lead to a Th2– and Treg-mediated immune response and thus to the IgG4-related disease.

The three main diagnostic criteria are: characteristic organ swelling or space-occupying mass on clinical examination or imaging, raised serum IgG4 concentration, and characteristic histology.

The histology is based on a lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate with IgG4-positive plasma cells that, mediated by the immune system, eventually leads to the histological features of storiform fibrosis and obliterating phlebitis. Eosinophilia can accompany IgG4-related disease.

The mainstay of treatment is steroid therapy, which achieves very good remission rates in all IgG4-related disease. Maintenance therapy with steroids can reduce the recurrence rate. In steroid-refractory cases, good results have been reported using the CD20 antibody rituximab.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

We thank the Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology of Ulm University Hospital for allowing us to use the MRI scans available.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

All the authors receive honoraria, e.g., lecture fees or reimbursement of travel expenses, from Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Falk, and Merck. They also receive consultancy fees from these companies. Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Celgene give financial support to studies carried out by the authors.

References

- 1.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H. Autoimmune pancreatitis is a systemic autoimmune disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2811–2812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1181–1192. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. A novel clinical entity, IgG4-related disease (IgG4RD): general concept and details. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10165-011-0508-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida K, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K. Prevalence of IgG4-related disease in Japan based on nationwide survey in 2009. Int J Rheumatol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/358371. www.hindawi.com/journals/ijr/2012/358371 (last accessed on 13. January 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritz S, Bergmann F, Grenacher L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis types 1 and 2. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1257–1265. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1104650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanno A, Nishimori I, Masamune A, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2012;41:835–839. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182480c99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Koyabu M, Miyoshi H, Takaoka M. Recent advances in the concept and diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related disease. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chari ST. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using its five cardinal features: introducing the Mayo Clinic’s HISORt criteria. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:39–41. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okazaki K, Umehara H. Are classification criteria for IgG4-RD now possible? The concept of IgG4-related disease and proposal of comprehensive diagnostic criteria in Japan. Int J Rheumatol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/357071. www.hindawi.com/journals/ijr/2012/357071 (last accessed on 13. January 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonstra K, Culver EL, de Buy Wenniger LM, et al. Serum immunoglobulin G4 and immunoglobulin G1 for distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:1954–1963. doi: 10.1002/hep.26977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, et al. Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and in distinguishing it from pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1646–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40:352–358. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182142fd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Heerde MJ, Biermann K, Zondervan PE, et al. Prevalence of autoimmune pancreatitis and other benign disorders in pancreatoduodenectomy for presumed malignancy of the pancreatic head. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2458–2465. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon SH, Kim MH, Park DH, et al. Is a 2-week steroid trial after initial negative investigation for malignancy useful in differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer? A prospective outcome study. Gut. 2008;57:1704–1712. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamisawa T, Chari ST, Giday SA, et al. Clinical profile of autoimmune pancreatitis and its histological subtypes: an international multicenter survey. Pancreas. 2011;40:809–814. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182258a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugumar A, Levy MJ, Kamisawa T, et al. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography criteria to diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis: an international multicentre study. Gut. 2011;60:666–670. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.207951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart PA, Topazian MD, Witzig TE, et al. Treatment of relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis with immunomodulators and rituximab: the Mayo Clinic experience. Gut. 2013;62:1607–1615. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubers LM, Maillette de Buy Wenniger LJ, Doorenspleet ME, et al. IgG4-associated cholangitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8430-2. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:706–715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Buy Wenniger LJ, Culver EL, Beuers U. Exposure to occupational antigens might predispose to IgG4-related disease. Hepatology. 2014;60:1453–1454. doi: 10.1002/hep.26999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Koyabu M, et al. IgG4 cholangiopathy—current concept, diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Hepatol. 2014;61 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami H, Zen Y, Kuwatani M, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune pancreatitis: histological assessment of biopsies from Vater’s ampulla and the bile duct. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1648–1655. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agaimy A, Ihrler S. Immunglobulin-G4(IgG4)-assoziierte Erkrankung. Pathologe. 2014;35:152–159. doi: 10.1007/s00292-013-1848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furukawa S, Moriyama M, Kawano S, et al. Clinical relevance of Kuttner tumour and IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialoadenitis. Oral Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1111/odi.12259. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/odi.12259/full (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornell LD. IgG4-related kidney disease. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2012;29:245–250. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khosroshahi A, Stone JH. Treatment approaches to IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:67–71. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328341a240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K, et al. Standard steroid treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:1504–1507. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.172908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, et al. Japanese clinical guidelines for autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009;38:849–866. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b9ee1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamisawa T, Okazaki K, Kawa S, et al. Amendment of the japanese consensus guidelines for autoimmune pancreatitis, 2013 III. Treatment and prognosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:961–970. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0945-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruyama M, Watanabe T, Kanai K, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis can develop into chronic pancreatitis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9 doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart PA, Kamisawa T, Brugge WR, et al. Long-term outcomes of autoimmune pancreatitis: a multicentre, international analysis. Gut. 2013;62:1771–1776. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Zhao L, Gao Y, et al. A classification of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis based on immunohistochemistry for IgG4 and IgG. Thyroid. 2014;24:364–370. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saeki T, Kawano M. IgG4-related kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014;85:251–257. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zen Y, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-related disease: a cross-sectional study of 114 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f7266b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyer A, Sadow PM, Bracamonte E, Gretzer M. Immunoglobulin G4-related retroperitoneal fibrosis of the pelvis. Rev Urol. 2014;16:92–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hui P, Mattman A, Wilcox PG, Wright JL, Sin DD. Immunoglobulin G4-related lung disease: a disease with many different faces. Can Respir J. 2013;20:335–338. doi: 10.1155/2013/418516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokura Y, Yagi H, Yanaguchi H, et al. IgG4-related skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2014;83:521–526. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Mikulicz-Radecki J. Über eine eigenartige symmetrische Erkrankung der Thränen- und Mundspeicheldrüsen. In: Czerny V, editor. Beiträge zur Chirurgie. Stuttgart: Festschrift gewidmet Theodor Billroth; 1892. pp. 610–630. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Yamamoto M, Harada S, Ohara M, et al. Clinical and pathological differences between Mikulicz’s disease and Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:227–234. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, Guien C. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas—an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis. 1961;6:688–698. doi: 10.1007/BF02232341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:732–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, et al. A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related autoimmune disease. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:982–984. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Khosroshahi A, Stone JH. A clinical overview of IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:57–66. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283418057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Stone JH, Khosroshahi A, Deshpande V, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of IgG4-related disease and its individual organ system manifestations. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3061–3067. doi: 10.1002/art.34593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Yadav D, Notahara K, Smyrk TC, et al. Idiopathic tumefactive chronic pancreatitis: clinical profile, histology, and natural history after resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:129–135. doi: 10.1053/cgh.2003.50016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Nirula A, Glaser SM, Kalled SL, Taylor FR. What is IgG4? A review of the biology of a unique immunoglobulin subtype. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:119–124. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283412fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Rispens T, Ooijevaar-de Heer P, Bende O, Aalberse RC. Mechanism of immunoglobulin G4 Fab-arm exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10302–103011. doi: 10.1021/ja203638y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Mahajan VS, Mattoo H, Deshpande V, Pillai SS, Stone JH. IgG4-related disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:315–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D. A concept on the role of helicobacter pylori infection in autoimmune pancreatitis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:196–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Frulloni L, Lunardi C, Simone R, et al. Identification of a novel antibody associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2135–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Wynn TA. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:583–594. doi: 10.1038/nri1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Al Zahrani H, Kyoung Kim T, Khalili K, et al. IgG4-related disease in the abdomen: a great mimicker. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2014;35:240–254. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Deshpande V, Khosroshahi A, Nielsen GP, Hamilos DL, Stone JH. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis is a form of IgG4-related systemic disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:701–706. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318213889e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Resheq YJ, Quaas A, von Renteln D, et al. Infiltration of peritumoural but tumour-free parenchyma with IgG4-positive plasma cells in hilar cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Sah RP, Chari ST. Serologic issues in IgG4-related systemic disease and autoimmune pancreatitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:108–113. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283413469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Masaki Y, Kurose N, Yamamoto M, et al. Cutoff values of serum IgG4 and histopathological IgG4+ plasma cells for diagnosis of patients with IgG4-related disease. Int J Rheumatol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/580814. www.hindawi.com/journals/ijr/2012/580814 (last accessed on 13. January 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), 2011. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s10165-011-0571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Sah RP, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis: an update on classification, diagnosis, natural history and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Ohara H, et al. Comparative evaluation of the Japanese diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2010;39:1173–1179. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f66cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Kamisawa T, Ryu JK, Kim MH, et al. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis: similarities and differences in Japan and Korea. Gut Liver. 2013;7:394–400. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.4.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Hoffmeister A, Mayerle J, Dathe K, et al. Method report to the S3 guideline chronic pancreatitis: definition, etiology, diagnostics and conservative, interventional endoscopic and surgical therapy of the chronic pancreatitis. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50:1225–1236. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Schorr F, Riemann JF. Pancreas duct stenosis of unknown origin. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134:477–480. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1208073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Buscarini E, De Lisi S, Arcidiacono PG, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography findings in autoimmune pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2080–2050. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i16.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Beyer G, Menzel J, Kruger PC, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138:2359–2374. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Tanaka A, Tazuma S, Okazaki K, et al. Nationwide survey for primary sclerosing cholangitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:43–50. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Maillette de Buy Wenniger LJ, Doorenspleet ME, Klarenbeek PL, et al. Immunoglobulin G4+ clones identified by next-generation sequencing dominate the B cell receptor repertoire in immunoglobulin G4 associated cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;57:2390–2398. doi: 10.1002/hep.26232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Ohara H, Okazaki K, Tsubouchi H, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis 2012. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:536–542. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0521-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Bhatti RM, Stelow EB. IgG4-related disease of the head and neck. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:10–16. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31827b619e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Harrison JD, Rodriguez-Justo M. IgG4-related sialadenitis is rare: histopathological investigation of 129 cases of chronic submandibular sialadenitis. Histopathology. 2013;63:96–102. doi: 10.1111/his.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Ahmed R, Al-Shaikh S, Akhtar M. Hashimoto thyroiditis: a century later. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:181–186. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182534868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Loane J, Jaramillo M, Young HA, Kerr KM. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis: a case report and literature review. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:640–641. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.8.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Saeki T, Nishi S, Imai N, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2010;78:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Alexander MP, Larsen CP, Gibson IW, et al. Membranous glomerulonephritis is a manifestation of IgG4-related disease. Kidney Int. 2013;83:455–462. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Takayama M, Hamano H, Ochi Y, et al. Recurrent attacks of autoimmune pancreatitis result in pancreatic stone formation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:932–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Yamamoto M, Nojima M, Takahashi H, et al. Identification of relapse predictors in IgG4-related disease using multivariate analysis of clinical data at the first visit and initial treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;54:45–49. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Khosroshahi A, Carruthers MN, Deshpande V, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of IgG4-related disease: lessons from 10 consecutive patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91:57–66. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182431ef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Umemura T, Zen Y, Hamano H, et al. Clinical significance of immunoglobulin G4-associated autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Stone JH. Ophthalmic manifestations of IgG4-related disease: single-center experience and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:806–817. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Kasashima S, Zen Y, Kawashima A, et al. A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1264–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.11.072. discussion 1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos P, et al. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence and associated diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:427–431. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.2.1740427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.Bando H, Iguchi G, Fukuoka H, et al. The prevalence of IgG4-related hypophysitis in 170 consecutive patients with hypopituitarism and/or central diabetes insipidus and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170:161–172. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.Buijs J, Maillette de Buy Wenniger L, van Leenders G, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related prostatitis: a case-control study focusing on clinical and pathologic characteristics. Urology. 2014;83:521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]