Abstract

Naturally-occurring epimutants are rare and have mainly been described in plants. However how these mutants maintain their epigenetic marks and how they are inherited remain unknown. Here we report that CHROMOMETHYLASE3 (SlCMT3) and other methyltransferases are required for maintenance of a spontaneous epimutation and its cognate Colourless non-ripening (Cnr) phenotype in tomato. We screened a series of DNA methylation-related genes that could rescue the hypermethylated Cnr mutant. Silencing of the developmentally-regulated SlCMT3 gene results in increased expression of LeSPL-CNR, the gene encodes the SBP-box transcription factor residing at the Cnr locus and triggers Cnr fruits to ripen normally. Expression of other key ripening-genes was also up-regulated. Targeted and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing showed that the induced ripening of Cnr fruits is associated with reduction of methylation at CHG sites in a 286-bp region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter, and a decrease of DNA methylation in differentially-methylated regions associated with the LeMADS-RIN binding sites. Our results indicate that there is likely a concerted effect of different methyltransferases at the Cnr locus and the plant-specific SlCMT3 is essential for sustaining Cnr epi-allele. Maintenance of DNA methylation dynamics is critical for the somatic stability of Cnr epimutation and for the inheritance of tomato non-ripening phenotype.

Spontaneous epimutations can result from heritable changes in DNA methylation without alteration in the underlying sequence, but these changes can influence gene expression and associated phenotypes1,2,3,4,5. Indeed epimutations can affect inbred traits in plants and animals6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However natural epigenetic variations are rare and little is known about how spontaneous epimutations retain their heritable stability1,2,3,4,5. In plants, methylation occurs at cytosines in CG, CHG and CHH contexts (where H = A, T, C) through the combined enzymatic activity of DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASEs (DRMs), METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (MET1) and the plant specific CHROMOMETHYLASEs (CMTs)15,16. These enzymes are required for RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) and methylation maintenance. In Arabidopsis, DRM2 catalyses de novo methylation in all sequence contexts and CMT2 is involved in non-symmetrical methylation while MET1, CMT3 and DRM2 participate in methylation maintenance at the CG, CHG and CHH sites, respectively15,16.

The tomato Colourless non-ripening (Cnr) is one of the best characterized naturally occurring epimutants3. Cnr differs from structural epi-variants such as CmWIP, FWA, FOLT1 and SP1117,18,19,20 in Arabidopsis, melon and Brassica, of which the epigenetic changes are either induced by transposon or trans-acting small RNAs, or genetic non-ripening mutants such as tomato rin, ripening-inhibitor21. Cnr contains eighteen hypermethylated cytosines in a 286-bp region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter at the Cnr locus and the Cnr epimutation and phenotype are very stable3. We only observed four Cnr fruits with revertant sectors showing red stripes out of thousands of fruits grown over more than twenty years. In this paper, using the spontaneous Cnr epimutant together with VIGS-based gene functional screening, targeted and whole-genome DNA methylation profiling and qRT-PCR assay, we investigate the mechanism responsible for somatic inheritance of Cnr. We unravel that SlCMT3 silencing results in reduction of DNA methylation and leads to Cnr-to-ripening reversion in tomato. Our results demonstrate that SlCMT3, possibly along with other key components including SlCMT2, SlDRM7 and SlMET1 in the RdDM and methylation maintenance pathways, is required to maintain the Cnr epi-allele, and CMT3 possesses an important role in epigenetic regulation of structural genes such as transcription factors in addition to its role in maintaining the methylation of repetitive DNA and transposon-related sequences.

Results

Silencing of DNA methylation-associated genes affects Cnr fruit ripening

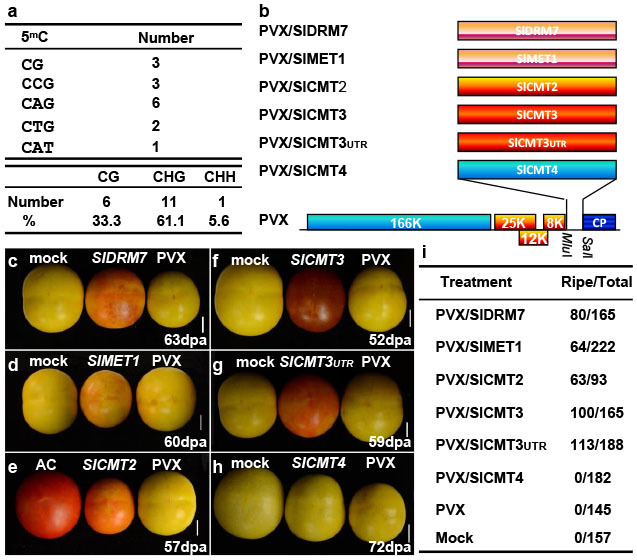

Cnr phenotype could be recreated in normal fruits by repression of LeSPL-CNR3,22 or by increasing methylation level in the 286-bp region23 (Supplementary Fig. 1), demonstrating that hypermethylation causes the phenotype. The eighteen hypermethylated cytosines in a 286-bp region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter are thought to be responsible for the non-ripening phenotype (Fig. 1a). To uncover the mechanism guarding the stability of the Cnr epi-allele, we used Potato virus X (PVX)-based VIGS3,22 to silence a range of DNA methylation-associated genes including SlDRM7, SlMET1, SlCMT2, SlCMT3 and SlCMT424 (Fig. 1b). These genes were selected based on sequence homology to the well-characterized Arabidopsis DNA-methyltransferases (DMTs; Supplementary Fig. 2). Specific cDNA fragments corresponding to each of the SlDMT genes were cloned into the PVX-based VIGS vector (Fig. 1b). It is worthwhile noting that nucleotide similarities among sequences of VIGS inducers are mostly around 30% or lower (Supplementary Table 1). Considering the requirement of perfect complementarity between silencing inducer and target sequences for small RNA (siRNA and microRNA)-mediated silencing in plants, we expect that these constructs including PVX/SlCMT2 and PVX/SlCMT3 should target their intended genes for gene-specific VIGS.

Figure 1. SlDMT silencing causes Cnr epimutant to ripening.

(a), Context, number and percentage of the hypermethylated cytosines (5mC) in the 286-bp LeSPL-CNR promoter region. (b), Diagram of VIGS vectors PVX/SlDRM7, PVX/SlMET1, PVX/SlCMT2, PVX/SlCMT3, PVX/SlCMT3UTR and PVX/SlCMT4. (c–h), Ripening in Cnr fruits, assessed by red colour as compared to wild-type fruits (AC, (e)). No ripening was observed in fruits mock-inoculated (mock), inoculated with PVX or PVX/SlCMT4 (h). Photographs were taken at the indicated day post-anthesis (dpa). Bar = 1 cm. (i), Number of ripening fruits out of total number of inoculated fruits from at least two independent experiments.

Indeed, Cnr fruits undergoing VIGS of SlDRM7, SlMET1, SlCMT2 and SlCMT3 ripened to various degrees (Fig. 1c–e, Supplementary Fig. 3a–n). Particularly VIGS of SlCMT3 by PVX/SlCMT3, targeting the coding region of SlCMT3 mRNA, caused Cnr fruits to reach the stage of losing chlorophyll (equivalent to breaker) approximately 4 days earlier than Cnr fruits mock-inoculated with TE buffer or injected with PVX (Supplementary Fig. 4). SlCMT3-silenced fruits continued to ripen almost completely (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 5a–h). PVX/SlCMT3UTR targeting the 3′-UTR of SlCMT3 mRNA could also trigger Cnr fruit ripening (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 6a–i). However, not all CMT genes are necessary for maintenance of Cnr since SlCMT4 silencing had no effect on ripening (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 3o), further demonstrating that the observed ripening phenotypes were resulted from gene-specific VIGS by specific SlDMT constructs (Fig. 1b–i).

More than 60% of fruits at 5–15 days post anthesis were injected with PVX/SlCMT3, PVX/SlCMT3UTR or PVX/SlCMT2 developed ripening phenotype. Only approximately 29% and 48% of fruits treated with PVX/SlMET1 or PVX/SlDRM7 appeared ripening. There was no ripening of Cnr fruits treated with PVX/SlCMT4, empty VIGS vector PVX, or mock-inoculated (Fig. 1i). It is worthwhile noting that no ripening was observed in rin fruits injected with PVX/SlCMT3 (Supplementary Fig. 3p). Taken together, our results demonstrate that functional SlDMTs in the RdDM and methylation maintenance pathways are required for maintain the somatic stability of the non-ripening Cnr phenotype in the natural epimutant.

Developmentally regulated SlCMT3 is likely the key modulator for maintaining the Cnr epi-allele

In Arabidopsis, CMT genes are predominantly associated with maintenance of cytosine methylation in transposable elements12,13,15. It is therefore surprising that silencing of SlCMT2 and SlCMT3 (a close relative of Arabidopsis CMT3) should rescue Cnr ripening. It is also intriguing that SlCMT3 silencing had a greater effect on reverting the Cnr phenotype than silencing of SlDRM7 (a homologue of the Arabidopsis de novo methyltransferase DRM2) or other SlDMTs (Fig. 1). These phenotypic differences may be due to variations in VIGS efficiencies, although this is unlikely because the PVX system is highly effective at silencing genes in tomato3,22. Alternatively, our results may suggest that SlCMT3 plays a more prominent role in maintaining epi-alleles such as Cnr than SlDRM7 and other SlDMTs. This is consistent with a high frequency of CHG hypermethylation in the LeSPL-CNR epimutated-region (Fig. 1a), the maintenance of which mainly requires functional SlCMT316. We interpret these data to mean that SlCMT3 is probably one of the key genetic regulators underlying the inheritable maintenance of Cnr epimutation.

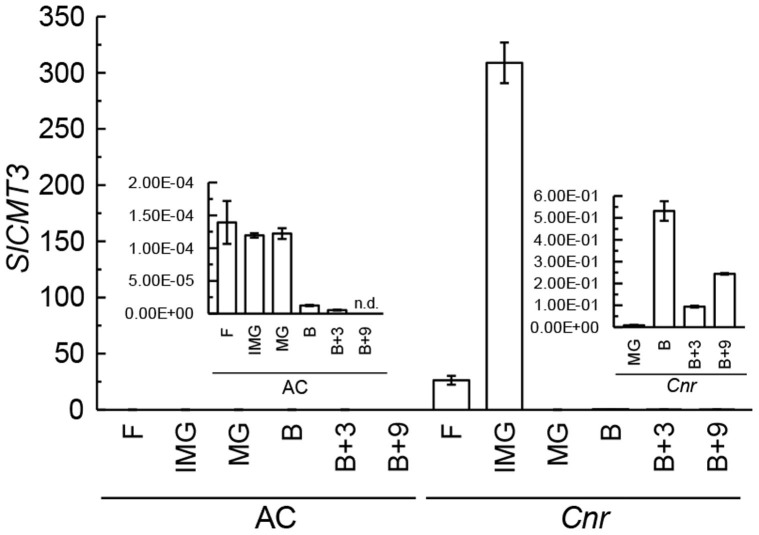

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that SlCMT3 expression is subject to developmental regulation. Expression of SlCMT3 changed dramatically in developing Cnr fruits, being extremely high at the immature stage then declining in mature green fruits (Fig. 2). The levels of SlCMT3 expression in immature Cnr fruits are so high that they dwarf those at all other stages of fruit development in normal and Cnr fruits (inset panels, Fig. 2). The SlCMT3 transcripts were again up-regulated in fruits at breaker before declining to lower levels in later stages. Expression of SlCMT3 in normal fruits was highest in green stages, but significantly lower than in immature Cnr fruits, and was down-regulated at breaker stage (Fig. 2). The prominent quantitative differences in expression of SlCMT3 between wild-type and Cnr fruits suggest that high level expression of SlCMT3 may be associated with the maintenance of the Cnr epi-status.

Figure 2. Developmental regulation of SlCMT3 expression.

Relative levels of SlCMT3 mRNA in fully-opened flowers (F) and pericarps from wild-type (AC) and Cnr epimutant fruits at immature green (IMG), mature green (MG), breaker (B), breaker + three days (B+3) and breaker + nine days (B+9) stages. The inset-figures have different y-axis scales to show the low levels of SlCMT3 mRNA at different ripening stages of in the AC and Cnr fruits. These values are dwarfed by the exceptionally high levels of expression of SlCMT3 in IMG Cnr fruit.

Silencing of SlCMT3 enhances LeSPL-CNR and other key ripening TF gene expression

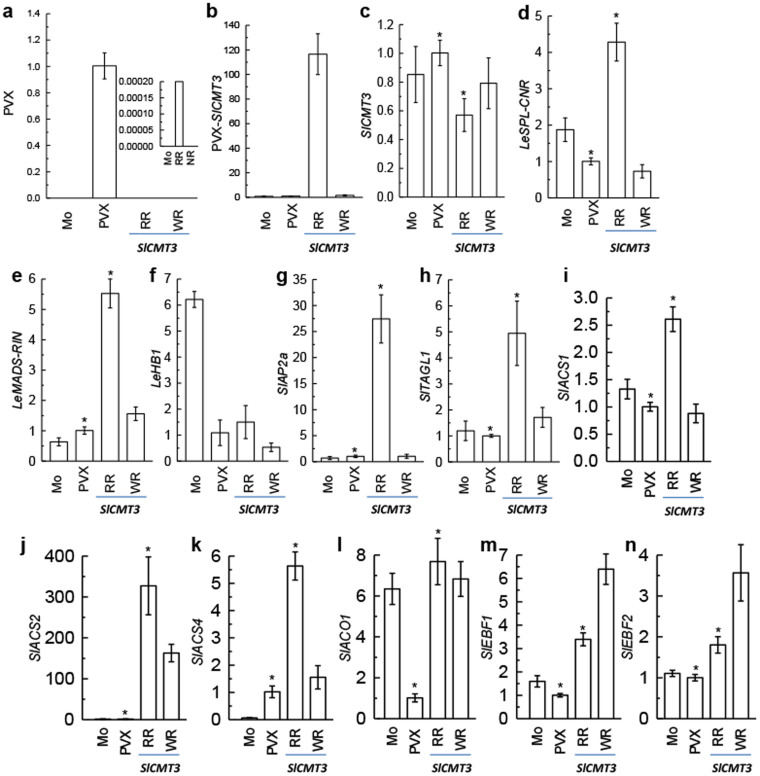

To dissect the mechanism by which SlCMT3 repression causes the reversion of the Cnr to ripening, we analyzed whether SlCMT3 silencing affects expression of LeSPL-CNR and other key ripening transcription factor (TF) genes including LeMADS-RIN, LeHB1, SlAP2a and SlTAGL122,25,26,27. Viral RNA declined dramatically in PVX/SlCMT3-injected fruits (Fig. 3a) and the silencing trigger SlCMT3 RNA was detected (Fig. 3b). Endogenous SlCMT3 mRNA in ripening pericarps was significantly reduced although only a moderate decrease was observed in the weakly ripe tissues of the same fruits (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 7a). In contrast with the reduction of SlCMT3 mRNA in silenced fruits, LeSPL-CNR was up-regulated when compared to levels in the control (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 7b). LeMADS-RIN, SlAP2a and SlTAGL1 were also up-regulated, although LeHB1 expression was not significantly affected (Fig. 3e–h, Supplementary Fig. 7c–f). It should be noted that all TFs tested are known to be developmentally regulated in normal and Cnr fruits, although their expression levels differ and are generally much lower in Cnr3,22,25,26,27 (Supplementary Fig. 7g–h). These results demonstrate that Cnr-to-ripening reversion by SlCMT3 silencing is inversely correlated not only to the expression of LeSPL-CNR, but also to that of other ripening-associated TF genes. However, how VIGS of SlCMT3 influences expression of additional ripening TF genes remains to be elucidated. It is possible that such an impact could be a secondary effect of ripening or the change of the LeSPL-CNR expression, or/and is due to altered methylation of promoters of these TF genes.

Figure 3. SlCMT3 affects expression of LeSPL-CNR and ripening genes.

(a), PVX RNA. (b), Silencing trigger RNA (PVX-SlCMT3). (c–n), Endogenous SlCMT3, LeSPL-CNR, LeMADS-RIN, LeHB1, SlAP2a, SlTAGL1, SlACS1, SlACS2, SlACS4, SlACO1, SlEBF1 and SlEBF2 mRNAs in non-ripening fruits mock-inoculated (Mo), inoculated with PVX, or in red-ripening (RR) and weak-ripening (WR) sectors of Cnr fruits inoculated with PVX/SlCMT3 (SlCMT3) at 31 days post inoculation. The inset-figure in (a) shows a low level of PVX RNA. Asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.001) by Student's t-tests between the SlCMT3-silenced and PVX control samples.

Silencing of SlCMT3 enhances expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis and signal transduction of the ripening hormone ethylene

We also examined the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes SlACS1, SlACS2, SlACS4 and SlACO1, and two ethylene signal transduction genes SlEBF1 and SlEBF224 during ripening of Cnr fruits. Consistent with up-regulation of ripening-associated TF gene expression, these ripening hormone-related genes were all found to be up-regulated in the ripe pericarp tissues in which SlCMT3 was silenced (Fig. 3i–m, Supplementary Fig. 8a–f). Indeed TFs such as LeMADS-RIN are known to regulate the expression of ethylene biosynthetic genes25. It is also possible that SlCMT3 is involved in the epigenetic regulation of these genes because levels of DNA methylation in their promoter regions in SlCMT3-silenced fruits were reduced, or that their up-regulation is the direct or indirect down-stream effect of LeSPL-CNR.

Silencing of SlCMT3 reduces cytosine methylation in the epimutated region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter

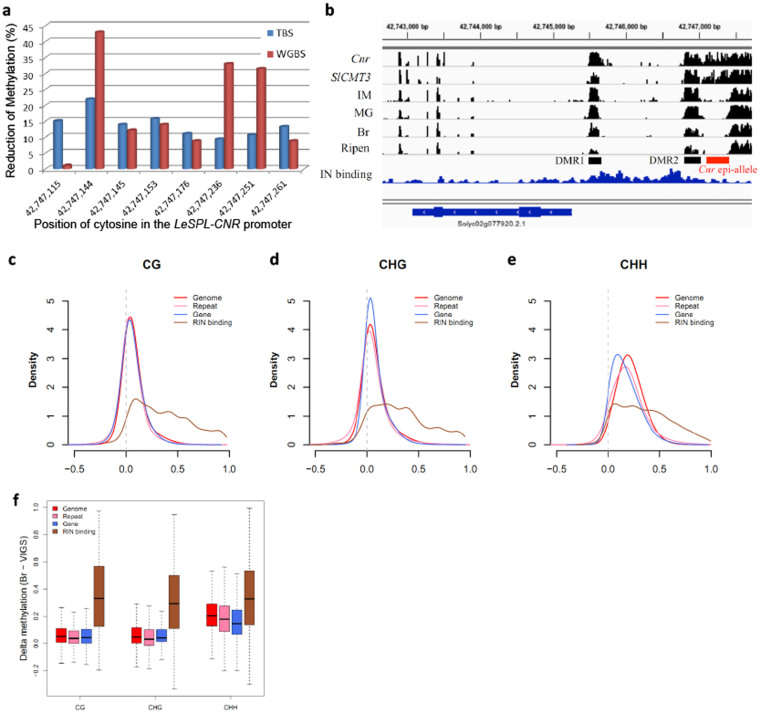

Targeted-bisulfite sequencing3 was used to examine methylation in the 286-bp region, and its flanking sequences, of the LeSPL-CNR promoter in the SlCMT3-silenced epi-allele fruits. A marked reduction of methylation was observed at eight specific cytosines, seven at the CHG sites and one in the CG context among the eighteen cytosine residues that are fully methylated in Cnr (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 9a–i). No clear difference in methylation was observed up- and downstream of the 286-bp region. These results indicate that the hypermethylation status of the eight cytosines is critical for inhibition of the LeSPL-CNR promoter activity, and the reduction in methylation of these residues may allow an increase in LeSPL-CNR expression; resulting in the “Cnr-to-ripening” reversion in the epimutant fruits. Taken into account of the gene-specific VIGS (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 3, 5, 6), the effect of SlCMT3 reduction on the eight specific cytosine residues seems to refine the Cnr epi-allele in terms of functional hypotethylation.

Figure 4. Analysis of single-base resolution methylome.

(a–b), Targeted and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (TBS, WGBS) reveals methylation changes in specific cytosine residues (a) and the overall Cnr promoter region (b) in the SlCMT-silenced Cnr fruit. Bar-chart shows the methylation levels in the Cnr gene locus in epimutant fruit at breaker stage (Cnr), SlCMT3-silenced Cnr fruit at breaker stage (VIGS), and in wild-type fruit at immature (IM), mature green (MG), breaker (Br), ripening stages (Ripen), and LeMADS-RIN ChIP-Seq (RIN binding). The location of the two differentially methylated regions (DMR1 and DMR2) and the epi-allele in the promoter region of Cnr are shown. (c–d), Genome-wide hypomethylation caused by SlCMT3 silencing. Kernel density plots of the loss of CG (c), CHG (d) and CHH (e) methylation in the SlCMT3-silenced Cnr fruit at breaker stage. Methylation differences (methylation level of Cnr minus SlCMT3 silenced Cnr fruit at breaker stage) of the whole-genome (bin = 1000 bp), annotated gene regions, repeats and the LeMADS-RIN bindings sites are shown, and regions with zero methylation are discarded29. (f), SlCMT3 silencing causes global demethylation in Cnr fruit. Boxplot showing the delta-methylation levels of Cnr and SlCMT3-silenced fruits at the breaker stage. For calculation of the global methylation delta, genome is divided into 200-bp bins and the methylation levels of each bin are calculated. Gene and the repeat are defined according to the ITAG v2.5 annotation. RIN binding sites are called as previously described29.

Effect of SlCMT3 silencing on whole-genome DNA methylation

The single-base resolution methylome of the SlCMT3-silenced Cnr fruit was further profiled by whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), and confirmed the loss of methylation at the eight specific cytosines in the 286-bp promoter region (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover we observed that genome-wide hypomethylation occurred at CHG as well as CG and CHH sites in repeats and gene regions (Fig. 4c–e). It is unlikely that the occurrence of hypomethylation at CG and CHH sites was due to non-specific silencing of other DMT genes by PVX/SlCMT3-mediated VIGS (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 3, 5, 6, 10), although the underlying mechanism for such reduction of methylation requires further investigation. On the other hand, it has been well-documented that LeMADS-RIN is required for the activation of fruit ripening genes by directly binding to promoters of those genes21,28,29. It has also been shown that LeMADS-RIN binding sites are demethylated in normal fruit and that LeMADS-RIN is unable to bind to the same sites in Cnr fruit due to a higher methylation level at those binding sites in Cnr than normal fruit29. We thus examined the methylation levels of LeMADS-RIN binding sites in our WGBS data and found that these sites became hypomethylated after SlCMT3 silencing (Fig. 4f). These findings suggest that SlCMT3 loss-of-function not only disrupted the Cnr epi-allele but might have also helped to elevate LeMADS-RIN expression (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 7c) that would allow functional restoration of the LeMADS-RIN activity for binding to these demethylated sites.

Discussion

We describe a mechanism that maintains the stability of a naturally occurring epimutation, and thus of its associated phenotype in tomato. This mechanism relies on SlCMT3, possibly along with other key components such as SlDRM7, SlCMT2 and SlMET1, in the RdDM and methylation maintenance pathways6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Silencing of SlCMT3 in the epimutant fruits reduces methylation of eight specific cytosines mostly in the CHG context in the region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter and causes genome-wide hypomethylation, resulting in an up-regulation of LeSPL-CNR and key ripening genes and “Cnr-to-ripening” reversion.

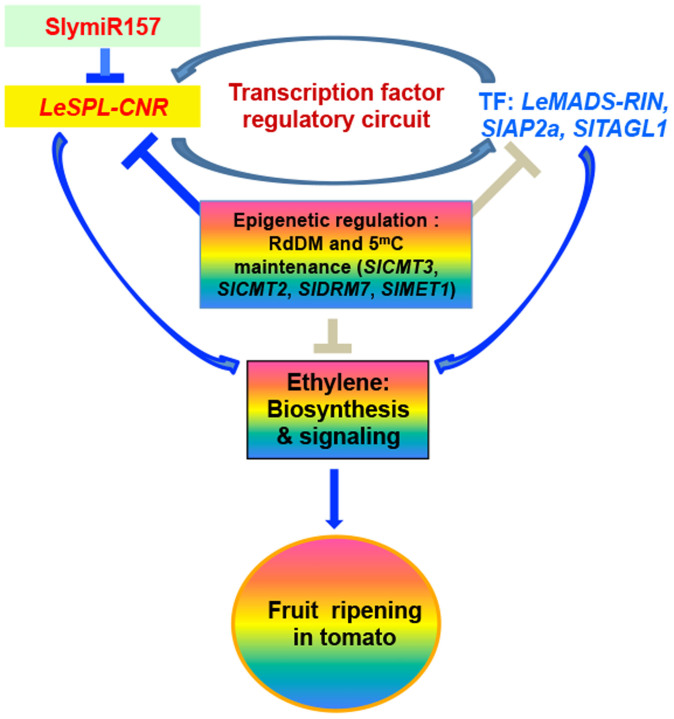

It is possible that the epi-allele LeSPL-CNR and key ripening-associated transcription factor (TF) genes including LeMADS-RIN, SlAP2a and SlTAGL1 form a regulatory network that controls tomato development and fruit ripening. These TFs can regulate each other and they are involved in possible feedback loops in the genetic regulation of ripening25,26,27,28. TFs also regulate fruit ripening via transcriptional regulation of ethylene biosynthesis and signalling25,26,27,28. In tomato, DNA methylation may also contribute to fruit ripening3,23,29. Consistent with this hypothesis, the content of globally methylated cytosine (5mC) is under dynamic changes during tomato development and fruit ripening, and chemical-mediated demethylation can facilitate early premature ripening24,28,31,32,33. In Cnr, DNA methylation maintenance is critical for maintaining epigenetic stability of the naturally occurring epimutation. Silencing of key SlDMTs in RdDM and 5mC maintenance pathways can destabilise epigenetic status which is required to down-regulate LeSPL-CNR. Such negative epigenetic control may also play a direct or indirect role in modulation of key ripening-associated TFs, and ethylene biosynthetic and signalling genes. Furthermore, microRNAs may be also involved in the fine-tuning of LeSPL-CNR expression in modulation of tomato fruit ripening34. Taken together, this model suggests that TFs, ethylene structural and signal transduction genes, microRNAs, epigenetic maintenance and developmentally regulated epigenetic modifying genes such as SlCMT3 involve tomato development and fruit ripening (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Maintenance of epigenetic stability in regulating tomato fruit ripening.

LeSPL-CNR and key ripening-associated transcription factor (TF) genes form a regulatory circuit in the genetic and epigenetic control of tomato fruit ripening via modulation of ethylene biosynthesis and signal transduction. Regulation of LeSPL-CNR expression by SlymiRNA157 is also incorporated into this model. Blue arrow indicates activation while the “T” sign represents inhibition. Grey arrow and “T” sign indicate potential functional mode.

In summary our results demonstrate that somatic maintenance of methylation may represent an essential layer of epigenetic regulation in addition to the complex genetic network for the stability of the Cnr epimutation and non-ripening phenotype. This idea is supported by that fruit development and ripening are associated with dynamic modifications of the whole-genome level of DNA methylation in normal tomato. Thus spontaneous, but stable, epigenetic mutations maintained by mechanisms such as those described in this work afford a new route for the evolution of modern plant species and in the case of crops such as tomato these altered phenotypes, if ‘beneficial', will be favored by natural selection and/or plant breeding.

Methods

Constructs

Non-translatable 300–525-bp fragments corresponding to the 5′ ends of each gene were PCR-amplified and cloned into the MluI/SalI sites of the Potato virus X (PVX) vector28 to generate PVX/SlDRM7, PVX/SlMET1, PVX/SlCMT2, PVX/SlCMT3, and PVX/SlCMT4 (Fig. 1b). The 3′ UTR of the SlCMT3 was also cloned into PVX to produce PVX/SlCMT3UTR. The full-length cDNA sequences of the nine tomato DMT genes and the sequences of the short non-translatable fragments that were used for construction of the PVX-based VIGS constructs are included in Supplementary Figure 10. A non-translatable LeSPL-CNR gene and the 286-bp region of the LeSPL-CNR promoter were cloned into the PVX/GFP vector3 to generate PVX/mLeSPL-CNR:GFP and PVX/Pcnr-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 1a). PVX encodes a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (166 K), movement proteins (25 K, 12 K and 8 K) and capsid protein (CP). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

PVX-based gene silencing and plant growth conditions

PVX-based VIGS and Virus-induced transcriptional gene silencing in Cnr, rin and wild-type tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Ailsa Craig) fruits were performed as described3,22. The carpopodium of tomato fruits at 5–15 days post anthesis was needle-injected with recombinant viral RNAs for each of the PVX-based VIGS constructs. Plants were grown in insect-free glasshouses at 25°C with supplementary lighting to give a 16-h photoperiod, examined and photographed with a Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tomato tissues using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using a FastQuant RT Kit (Tiangen). qRT-PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad) using an UltraSYBR Mixture Kit (CoWin Bioscience). At least three technical replicates for each of three biological replicates for each sample were analyzed. The relative level of specific gene expression was calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCt and normalized to the amount of 18S rRNA detected in the same sample as described30.

Bisulfite sequencing

Total DNA was isolated from tomato tissues using DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Bisulfite conversion, PCR amplification and sequencing were performed using the EZ DNA Gold Methylation Kit (Zymo Research), Blue MegaMix Double PCR mixture (Microzone) and BigDye Terminator Reaction Mixture (Applied Biosystems) as described3. Whole genome bisulfite sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were performed as previously described29.

Author Contributions

W.C., J.K., C.Q. and Y.H. designed and performed experiments; J.T., C.W., H.W., Y.S., C.L., B.L., P.Z., Y.W., T.L. Z.Y., X.Z. and N.S. performed experiments; Y.C., S.Y. and S.Z. performed the WGBS and analysed the data; H.-z.W., T.O., Y.L., K.M., S.J., D.R., S.Z. and G.B.S. were involved in discussions and helped writing the paper; P.G. analysed data and helped writing the paper; Y.H. initiated the project, analysed data and wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank D. C. Baulcombe for providing the original PVX vector. This work was in part supported by a Pandeng Pragramme from Hangzhou Normal University (201108), an Innovative Grant for Science Excellence from Hangzhou City Education Bureau, China and the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council core funding (BBS/E/H/00YH0271) to Y.H., and by the General Research Fund 14119814 and the State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology Fund 8300063 to S.Z. G.B.S. was funded from the TomNet project sponsored by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. We also thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31370180, 31401926, 31200913, 31201490) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LQ13C020004, LQ13C060003, LQ12C02005, LY14C010005) for supports.

References

- Patterson G. I., Thorpe C. J. & Chandler V. L. Paramutation, an allelic interaction, is associated with a stable and heritable reduction of transcription of the maize b regulatory gene. Genetics 135, 881–894 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P., Vincent C. & Coen E. An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 401, 157–161 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning K. et al. A naturally occurring epigenetic mutation in a gene encoding an SBP-box transcription factor inhibits tomato fruit ripening. Nature Genet. 38, 948–952 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K. et al. A metastable DWARF1 epigenetic mutant affecting plant stature in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11218–11223 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira A. B. et al. Extensive natural epigenetic variation at a de novo originated gene. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003437 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth A. et al. Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for maintenance of CpXpG methylation. Science 292, 2077–2080 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J., Lindroth A., Cao X. & Jacobsen S. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416, 556–560 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman D., Cao X. & Jacobsen S. ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation. Science 299, 716–719 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler V. & Stam M. Chromatin conversations: Mechanisms and implications of paramutation. Nature Rev. Genet. 5, 532–544 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S., Henderson I. & Jacobsen S. Gardening the genome: DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Rev. Genet. 6, 351–360 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleman M. et al. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is required for paramutation in maize. Nature 442, 295–298 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards E. J. Inherited epigenetic variation - revisiting soft inheritance. Nature Rev. Genet. 7, 395–401 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R. & Jacobsen S. E. Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 447, 418–424 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S., Baumberger R. & Grossniklaus U. Epigenetic variation, inheritance, and selection in plant populations. Cold Spring Harb. Symp, Quant. Biol. 77, 97–104 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J. A. & Jacobsen S. E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plant s and animals. Nature Rev. Genet. 11, 204–220 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemach A. et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell 153, 193–205 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. et al. A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature 461, 1135–1138 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto R. et al. Epigenetic variation in the FWA gene within the genus Arabidopsis. Plant J. 66, 831–843 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand S. et al. Rapid establishment of genetic incompatibility through natural epigenetic variation. Curr. Biol. 22, 326–331 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarutani Y. et al. Trans-acting small RNA determines dominance relationships in Brassica self-incompatibility. Nature 466, 983–986 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrebalov J. et al. A MADS-box gene necessary for fruit ripening at the tomato ripening-inhibitor (rin) locus. Science 296, 343–346 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z. F. et al. A tomato HD-Zip homeobox protein, LeHB-1, plays an important role in floral organogenesis and ripening. Plant J. 55, 301–310 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A. et al. Virus-mediated efficient induction of epigenetic modifications of endogenous genes with phenotypic changes in plants. Plant J. 65, 156–168 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssier E. et al. Tissue dependent variations of DNA methulation and endoreduplication levels during tomato fruit development and ripening. Planta 228, 391–399 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee H. J. & Giovannoni J. J. Genetics and control of tomato fruit ripening and quality attributes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 41–59 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlova R. et al. Transcriptome and metabolite profiling show that APETALA2a is a major regulator of tomato fruit ripening. Plant Cell 23, 923–941 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrebalov J. et al. Fleshy fruit expansion and ripening are regulated by the tomato SHATTERPROOF gene TAGL1. Plant Cell 21, 3041–3062 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T. et al. Virus-induced gene complementation reveals a transcription factor network in modulation of tomato fruit ripening. Sci. Rep. 2, 836 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S. et al. Single-base resolution methylomes of tomato fruit development reveal epigenome modifications associated with ripening. Nature Biotechnol. 31, 154–159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C. et al. Involvement of RDR6 in short-range intercellular RNA silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. Sci. Rep. 2, 467 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Kimatu J. N., Xu K. & Liu B. DNA cytosine methylation in plant development. J. Genet. Genomics 37, 1–12 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messeguer R., Ganal M. W., Steffens J. C. & Tanksley S. D. Characterization of the level, target sites and inheritance of cytosine methylation in tomato nuclear DNA. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 753–770 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. et al. Tuning LeSPL-CNR expression by SlymiR157 affects tomato fruit ripening. Sci. Rep. 5, 7852 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information