Summary

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the validity and reliability of air displacement plethysmography (ADP) compared to a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) criterion for body composition measurement in overweight and obese women (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg m2).

Subjects/Methods

Twenty-four overweight and obese women (Mean ± SD; Age: 36.6 ± 12.0 years; Height: 166.4 ± 5.8 cm; Weight: 86.5 ± 14.2 kg; Body Fat: 38.5 ± 3.7%; BMI: 31.3 ± 5.5 kg m2) were tested after an 8-h fast. Fat mass (FM), fat-free mass (FFM) and percent body fat (%BF) were measured by ADP and compared to values determined by the DXA criterion. FFM from DXA was calculated as lean mass plus bone mineral content. A paired samples t-test was used to test for significant differences in the body composition variables between methods. A one-way ANOVA along with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), SEM,%SEM and MD was used to represent reliability.

Results

Validity data comparing ADP and DXA demonstrated no significant difference in FM (ADP-DXA FM = 0.99 kg; P = 0.113), FFM (0.98 kg; P = 0.115) and %BF (1.56%; P = 0.540). Reliability data for ADP between the first and second trials showed no significant difference in FM (P = 0.168; ICC = 0.994; SEM = 0.668), FFM (P = 0.058; ICC = 0.973; SEM = 0.892) or %BF (P = 0.121; ICC = 0.971; SEM = 0.813).

Conclusions

For overweight and obese women, ADP was found to be a valid measure of FM, FFM and %BF when compared with DXA. The reliability of ADP was supported for all body composition variables.

Keywords: dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, fat-free mass, percent body fat, sensitivity, sex

Introduction

Body composition is an important measure of health and nutritional status. As of 2010, 66% of Americans older than 20 years were reported to be overweight, and more than 35% of American adults and 15% of American children were considered obese (Ogden et al., 2012). These numbers have been steadily increasing over the last 20 years. Due to the rise in obesity, it is imperative to have valid and reliable body composition assessment tools to accurately classify overweight individuals, to prescribe correct exercise and nutrition interventions, and to detect body composition changes.

Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a common technique that assumes the human body can be subdivided into three compartments (3C): fat mass (FM), bone-free lean mass (LM) and bone mineral content (BMC) (Norcross & Van Loan, 2004). In clinical medicine, DXA is considered one of the most precise assessments of body composition when bone mineral density is taken into account (Brownbill & Ilich, 2005). However, due to obesity, subjects may be too wide, thick or heavy for the DXA; therefore, due to size limitations, DXA may not be the most appropriate assessment (Duren et al., 2008). In addition, DXA instruments are costly, not easily accessible to the public and give off small amounts of radiation during the total body scans. Therefore, other instruments should be considered when measuring body composition in special populations such as those that are too large or those that cannot tolerate radiation (i.e. pregnant women, cancer patients, children).

Air displacement plethysmography (ADP) is another technique that uses measurements of body density for body composition estimation (Levenhagen et al., 1999). This technique calculates body volume by measuring the volume of displaced air by a subject inside the machine (Lee & Gallagher, 2008). ADP has several advantages over DXA in that it is easy to use, it is less expensive and it does not expose subjects to radiation. In addition, ADP can measure subjects of various sizes (Minderico et al., 2006), requires less technician training (McCrory et al., 1995) and has been found to be reliable in various populations (Miller & Diamond, 2005), (Noreen & Lemon, 2006). However, little research has been conducted to assess ADP's validity and reliability in overweight women.

To date, we are aware of only two previous studies that have evaluated the agreement between ADP and DXA in an overweight population (Levenhagen et al., 1999) (Minderico et al., 2006). However, there has yet to be a single, specific evaluation in overweight and obese women. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the validity and reliability of ADP compared to a DXA criterion for body composition measurement in overweight and obese women.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Twenty-four Caucasian (n = 17) and African American (n = 7) overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) and obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) women volunteered to participate in this study. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The experiments on subjects were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the University's Institutional Review Board. All subjects read, understood and provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Subjects reported to the Applied Physiology Laboratory after an eight-hour fast for two separate visits at least 24–48 h, but no more than 72 h apart. During the first visit, the subjects underwent ADP and DXA testing. The second visit consisted of only ADP testing.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics (n = 24).

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.6 ± 12.0 | 20.0–54.0 |

| Height (cm) | 166.4 ± 5.8 | 156.8–178.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 86.5 ± 14.2 | 62.9–117.4 |

| Body fat (%) | 38.5 ± 3.7 | 32.5–45.7 |

| Body mass index (kg m2) | 31.3 ± 5.5 | 25.0–45.6 |

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

Whole body composition was measured on a Hologic Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometer (DXA; Hologic Discovery W, Bedford, MA, USA) using the device's default software (Apex Software Version 3.3; Hologic Discovery W, Bedford, MA, USA). The device used rectilinear fan beam acquisition to give measurements for fat mass (FM; kg), lean mass (LM; kg), percent body fat (%BF;%) and bone mineral content (BMC; kg). In accordance with Bertoli et al. (2008), FFM values from DXA were calculated as LM + BMC. After removing all metal objects from their person, subjects laid supine in the middle of the platform with hands facedown near their sides; if necessary, thumbs were placed under their buttocks to maintain width restrictions. Subjects were instructed to remain still and breathe normally for the duration of the scan. All scans were performed by the same individual. The device was calibrated according to the manufacturer before testing occurred to ensure valid results.

Air displacement plethysmography

Air Displacement Plethysmography (ADP; BodPod®; COSMED USA, Inc., Concord, CA, USA) was used to estimate body volume after an eight-hour fast using the device's default software (Software Version 4.2+, COSMED USA, Inc.). Prior to each test, the BodPod was calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions. The subjects' weight and body volume were measured and used to determine fat mass (FM; kg), fat-free mass (FFM; kg) and percent body fat (%BF;%). The Brozek et al. (1963) and Siri (1956) equations were used to estimate body composition for Caucasian and African American women, respectively.

Statistical analysis

To test for significant differences in FM, FFM and %BF between the ADP and DXA methods, a paired samples t-test was used. In addition, a Pearson's product-moment correlation was used to determine the relationship between the two methods. The Bland and Altman method was used to calculate the limits of agreement between ADP and DXA for the assessment of FM, FFM and %BF (Bland & Altman, 1986). To examine ADP reliability for all variables across testing days 1 and 2, a one-way repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. Also for reliability, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), standard error of the mean (SEM), percent standard error of the mean (%SEM) and minimal difference (MD) were calculated to examine the sensitivity for all body composition variables. The ICC was calculated with the following equation (Weir, 2005):

All components of the ICC equation were derived from the output of the one-way ANOVAs. MSS represents the mean square for subjects, MSE is the mean square error, MST is the mean square for trial, k represents the number of trials and n is the sample size. The SEM for this model was calculated using the following equation (Hopkins, 2000):

SPSS Version 20 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the paired samples t-test and the one-way ANOVA. A custom-written spreadsheet was used to calculate ICC, SEM, % SEM and MD. An alpha level was set at P≤0.05 a priori.

Results

Validity of body composition with ADP and DXA

Validity statistics for FM, FFM and %BF between ADP and DXA are presented in Table 2. A paired samples t-test revealed no significant difference for FM measured by ADP compared to DXA (mean difference ± SD; Δ 0.99 ± 2.97 kg; P = 0.113). There was no significant difference between ADP and DXA methods in FFM (Δ 0.98 ± 2.92 kg; P = 0.115). There was no significant difference in %BF between ADP and DXA measurements (Δ 1.56 ± 3.75%; P = 0.540). Pearson's product-moment correlation demonstrated a significant correlation for FM, FFM and %BF between ADP and DXA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Validity statistics for the body composition variables between air displacement plethysmography (ADP) and Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

| Fat mass (FM; kg) | Fat-free mass (FFM; kg) | Body fat% (%BF; %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADP (mean ± SD) | 34.39 ± 9.05 | 52.07 ± 5.82 | 40.09 ± 4.95 |

| DXA (mean ± SD) | 33.39 ± 7.79 | 53.05 ± 6.77 | 38.53 ± 3.70 |

| r | 0.95* | 0.90* | 0.66* |

r, Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient.

Significance at P≤0.05.

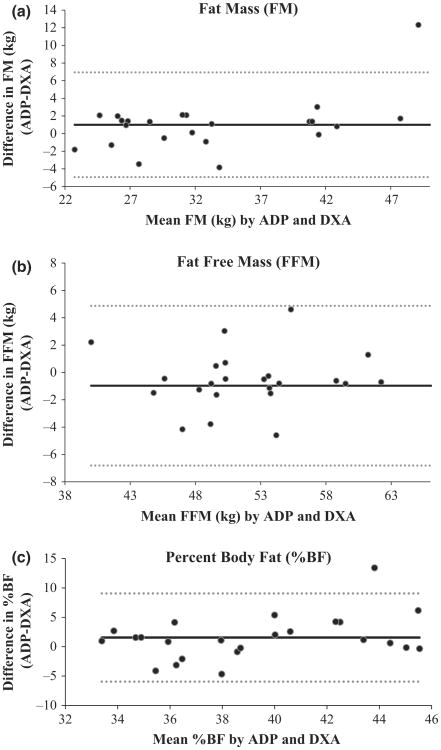

Bland–Altman analyses were performed for FM, FFM and % BF to determine if bias existed between ADP and DXA, with plots shown in Fig. 1. A non-significant trend was observed for each body composition variable, indicating no bias between the two measurement methods.

Figure 1.

(a) The Bland–Altman analysis for Fat mass (FM). The middle solid line represents the mean difference between FM (kg) from air displacement plethysmography (ADP) – FM (kg) from Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and the upper and lower dashed lines represent ± 2 SD from the mean. Bias between ADP and DXA was not observed for FM, as indicated by a non-significant P value (P = 0.113). (b) The Bland-Altman analysis for Fat-free mass (FFM). The middle solid line represents the mean difference between FFM (kg) from ADP – FFM (kg) from DXA and the upper and lower dashed lines represent ± 2 SD from the mean. A nonsignificant P value (P = 0.115) indicated no bias between ADP and DXA for FFM (kg). (c) The Bland-Altman analysis for percent body fat (%BF). The middle solid line represents the mean difference between %BF from ADP–%BF from DXA and the upper and lower dashed lines represent ± 2 SD from the mean. Bias between ADP and DXA was not observed for %BF, as indicated by a non-significant P value (P = 0.540).

Reliability of ADP

The reliability statistics for FM, FFM and %BF for trials 1 and 2 are presented in Table 3. A one-way repeated-measure ANOVA revealed no significant difference between trials 1 and 2 in measures of FM (Δ 0.275 ± 0.194 kg; P = 0.168), FFM (Δ −0.510 ± 0.363 kg; P = 0.058) or %BF (Δ 0.378 ± 0.267%; P= 0.121). Reliability values (Table 3) demonstrate strong reliability in overweight/obese women.

Table 3.

Reliability statistics for body composition variables in trials 1 and 2.

| Fat mass (FM; kg) | Fat-free mass (FFM; kg) | Body fat% (%BF; %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 (mean ± SD) | 34.385 ± 9.046 | 52.074 ± 5.817 | 40.086 ± 5.048 |

| Visit 2 (mean ± SD) | 34.110 ± 8.993 | 52.587 ± 5.654 | 39.707 ± 4.924 |

| ICC2,1 | 0.994 | 0.973 | 0.971 |

| SEM | 0.668 | 0.892 | 0.813 |

| %SEM | 1.952 | 1.704 | 2.038 |

| MD | 1.85 | 2.47 | 2.25 |

ICC2,1, intraclass correlation coefficient, model 2,1 [14]; SEM, standard error of measurement; SEM%, standard error of measurement expressed as a percentage of the mean; MD, minimum difference to be considered real.

Discussion

This study examined FM, FFM and %BF to evaluate the validity and reliability of ADP to the DXA criterion for body composition measurement in overweight and obese women. ADP was found to be a valid measure of FM, FFM and %BF. When compared to DXA, ADP non-significantly (P = 0.113–0.540) overestimated FM (Δ 0.99 ± 2.97 kg) and %BF (Δ 1.56 ± 3.75 kg), while FFM (Δ 0.98 ± 2.92 kg) values were non-significantly (P = 0.115) underpredicted. ADP was also found to be a reliable measure of FM (ICC = 0.994), FFM (ICC = 0.973) and %BF (ICC = 0.971) when two trials were performed across testing days.

DXA is a commonly used technique for body composition measurement and has been considered an appropriate alternative to a multicompartment model (Minderico et al., 2006). Additionally, DXA is typically used due to its three-compartment evaluation, accounting for FM, LM and BMC. Several studies have compared ADP to DXA in diverse populations, such as elderly men and women (Bertoli et al., 2008), healthy men and women (Levenhagen et al., 1999), healthy women (Minderico et al., 2006) and young adolescents (Radley et al., 2003), demonstrating a range of results. In elderly men and women, Bertoli et al. (2008) found ADP to be an invalid (P = 0.001) comparison to DXA when assessing FFM (Δ 2.8 kg), especially in men. In contrast, the current study utilized similar FFM calculations, and found ADP and DXA to produce valid estimates of FFM in overweight/obese women. In support, Levenhagen et al. (1999) found ADP to be highly correlated with DXA in men (r = 0.94) and women (r = 0.78) when measuring %BF across a wide range of body fat percentages (6.0–41.0%). In healthy, overweight and obese females, Minderico et al. (2006) demonstrated ADP to be invalid against DXA in measuring FM, FFM and %BF before and after a weight-loss programme. However, Radley et al. (2003) validated ADP %BF against DXA in young male and female adolescents, yielding no significant differences. The current study is believed to be the first to examine the validity of ADP in comparison to DXA for measurements of FM, FFM and %BF in exclusively overweight women, while also taking into account race specific considerations for ADP calculations. Body composition differences exist between men and women for any given body mass index, due to higher adiposity in women and varying regional distributions in men (Geer & Shen, 2009). It is therefore important to have assessments that will accurately measure and track changes in body composition compartments in women, especially for those that are overweight or obese.

Results from the present study demonstrated that ADP and DXA yield similar results for FM (Δ 0.99 ± 2.97 kg), supporting the results of Edwards et al. (2011), reporting significantly accurate FM results from ADP in college-aged females, when compared to DXA. In contrast, Minderico et al. (2006) utilized the Siri body density formula and is the only study that has indicated significantly higher DXA FM measures in overweight and obese women. The current study suggests that when utilizing the appropriate body density formula, such as Brozek et al. (1963) and Siri (1956) equations for Caucasian and African American women, respectively, ADP can accurately predict FM in overweight and obese women.

Fat-free mass values from the current study did not demonstrate significant differences between ADP and DXA (Δ 0.98 ± 2.92 kg; P = 0.115) when calculating DXA FFM from LM + BMC. However, when using only LM values, there was a significant difference (Δ 1.38 ± 2.89 kg; P = 0.029; full results not presented) between methods, yielding the importance of appropriate FFM calculations when using DXA for estimates in an overweight/obese population. The current study's findings with FFM are different than those of Bertoli et al. (2008) in a study evaluating men, despite using the same calculation for FFM. In addition, while the calculations for FFM were not disclosed, Minderico et al. (2006) demonstrated significant differences in FFM in women. To date, other than the present study, no studies have found ADP FFM values to be valid in comparison to DXA. The current study suggests that FFM can be accurately predicted by ADP in overweight and obese women, when compared to the appropriate FFM calculation from DXA (LM + BMC).

Furthermore, the %BF values from ADP in the current study were valid compared to the DXA criterion (Δ 1.56 ± 3.75%; P = 0.540). Results of Levenhagen et al. (1999), Miller & Diamond (2005), and Radley et al. (2003) also suggest accurate %BF measurements between the two devices. In opposition to these results, Minderico et al. (2006) found %BF to be significantly higher when measured by DXA. To account for race differences, the current study employed Siri (1956) and Brozek et al. (1963) equations to measure African American and Caucasian women, respectively. The Siri and Brozek equations are commonly used for calculations by the ADP equipment utilized in this study. Two of the above studies used Siri and Lohman (Radley et al., 2003) or Siri and Schutte (Levenhagen et al., 1999) equations for racial differences. Despite the varying equations, ADP predictions of %BF seem to be comparable to DXA %BF values in overweight and obese, African American and Caucasian women.

In addition to establishing validity, ADP was found to be reliable in assessing FM (Δ 0.275 ± 0.194 kg), FFM (Δ −0.510 ± 0.363 kg), or %BF (Δ 0.378 ± 0.267 kg) between trials in overweight and obese women. Small SEM values from ADP (Table 3) demonstrate the sensitivity and ability to measure minor changes in body composition. Miller & Diamond (2005) and Noreen & Lemon (2006) have demonstrated similar results in measuring %BF in healthy men and women, through a broad range of body weights. These results contrast with evidence found by one previous study (Anderson, 2007), which found high reliability for within-day measurements, but not for between-day measurements. To date, no other studies have presented the reliability of ADP in measuring FM and FFM exclusively in overweight and obese women.

The results of this study can be applied to real-world situations in which body composition needs to be measured. Less costly than DXA, ADP is a valid and sensitive tool that could be utilized in various settings, such as weight-loss facilities, fitness centres, and hospitals, to detect small changes in FM, FFM, and %BF. A limitation to the current study was that the study population was not inclusive. A sample size that included both overweight and obese individuals was used, potentially confounding validity results when morbidly obese individuals are assessed. In addition, only African American and Caucasian subjects participated. Therefore, results are not generalizable to other populations, such as non-overweight and obese, ethnicities other than Caucasian and African American, and men.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that when compared to DXA, ADP is a valid measure of FM, FFM and % BF in overweight and obese women. In addition, ADP is a reliable measure of FM, FFM and %BF between trials. ADP is a valid, reliable and simple technique that can be used to estimate body composition in overweight and obese women. Future research should be conducted to evaluate the ability of each device to track body composition changes in overweight and obese women following a weight loss or training intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Nutrition Obesity Research Center (P30DK056350).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson DE. Reliability of air displacement plethysmography. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21:169–172. doi: 10.1519/00124278-200702000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoli S, Battezzati A, Testolin G, Bedogni G. Evaluation of air-displacement plethysmography and bioelectrical impedance analysis vs dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for the assessment of fat-free mass in elderly subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownbill RA, Ilich JZ. Measuring body composition in overweight individuals by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. BMC Med Imaging. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek J, Grande F, Anderson JT, Keys A. Densitometric analysis of body composition: revision of some quantitative assumptions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;110:113–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb17079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duren DL, Sherwood RJ, Czerwinski SA, Lee M, Choh AC, Siervogel RM, Cameron Chumlea W. Body composition methods: comparisons and interpretation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:1139–1146. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HL, Randall Simpson JA, Buchholz AC. Air displacement plethysmography for fat-mass measurement in healthy young women. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2011;72:85–87. doi: 10.3148/72.2.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geer EB, Shen W. Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance. Gend Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000;30:1–15. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Gallagher D. Assessment methods in human body composition. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:566–572. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32830b5f23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenhagen DK, Borel MJ, Welch DC, Piasecki JH, Piasecki DP, Chen KY, Flakoll PJ. A comparison of air displacement plethysmography with three other techniques to determine body fat in healthy adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1999;23:293–299. doi: 10.1177/0148607199023005293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory MA, Gomez TD, Bernauer EM, Mole PA. Evaluation of a new air displacement plethysmograph for measuring human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1686–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Diamond JL. Accuracy and reliability of body composition measurements using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and air displacement plethysmography. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S302–S303. [Google Scholar]

- Minderico CS, Silva AM, Teixeira PJ, Sardinha LB, Hull HR, Fields DA. Validity of air-displacement plethysmography in the assessment of body composition changes in a 16-month weight loss program. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2006;3:32. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J, Van Loan MD. Validation of fan beam dual energy x ray absorptiometry for body composition assessment in adults aged 18-45 years. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:472–476. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.005413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noreen EE, Lemon PW. Reliability of air displacement plethysmography in a large, heterogeneous sample. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1505–1509. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000228950.60097.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;82:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley D, Gately PJ, Cooke CB, Carroll S, Oldroyd B, Truscott JG. Estimates of percentage body fat in young adolescents: a comparison of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and air displacement plethysmography. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1402–1410. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri WE. The gross composition of the body. Adv Biol Med Phys. 1956;4:239–280. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4832-3110-5.50011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–240. doi: 10.1519/15184.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]