Abstract

Objective

To examine the relation between “sexting,” (sending and sharing sexual photos online via text messaging and in-person) with sexual risk behaviors and psychosocial challenge in adolescence.

Methods

Data were collected online between 2010 and 2011 with 3,715 randomly selected 13- to 18-year-old youth across the United States.

Results

Seven percent of youth reported sending or showing someone sexual pictures of themselves, where they were nude or nearly nude, online, via text messaging, or in-person, during the past year. Although females and older youth were more likely to share sexual photos than males and younger youth, the profile of psychosocial challenge and sexual behavior was similar for all youth. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, sharing sexual photos was associated with all types of sexual behaviors assessed (e.g., oral sex, vaginal sex) as well as some of the risky sexual behaviors examined—particularly having concurrent sexual partners and having more past-year sexual partners. Adolescents who shared sexual photos also were more likely to use substances and less likely to have high self-esteem than their demographically similar peers.

Conclusions

While the media has portrayed “sexting” as a problem caused by new technology, health professionals may be more effective by approaching it as an aspect of adolescent sexual development and exploration and, in some cases, risk-taking and psychosocial challenge.

Keywords: Sexual behavior, adolescents, media, sexting, sexual risk, psychosocial functioning

Introduction

“Sexting” originated as a media term [1] that generally refers to sending sexual images via text messaging and can also include uploading sexual pictures to websites. “Sexting” has received attention from legal scholars because some youth are creating and distributing images that meet definitions of child pornography under criminal statutes [2]. Whether there are adolescent health implications, however, is less well understood. In a study of high school students across 7 schools in Texas state, youth who reported sharing sexual photos of themselves were more likely to be dating and to have had sex [3]. The study also found that “sexting” was a marker for risky sexual behavior for female but not male students. On the other hand, among high school student participants in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in Los Angeles, “sexting” was associated with being sexually active, but not necessarily with a lack of condom use [4]. This would suggest that sharing or posting sexual pictures is reflective of typical sexual expression in romantic relationships among adolescents. Studies of young adults also are conflicting; some have found “sexting” is associated with risky sexual behavior [5], while others have not [6, 7]. Further research is needed before more concrete conclusions can be drawn about where “sexting” falls on the spectrum of healthy versus risky sexual behavior for young people [8].

The importance of studying “sexting” at the national level is evident by the wide variation in prevalence rates between regional and national studies. Although regional studies report that between 15% [4] and 28% [3] of high school-aged youth have sent a sexual photo, national studies among adolescents report much lower rates (3% [9] and 4% [10]). Rates may differ for a variety of reasons, including: age variation of youth across studies, variations in behaviors in urban versus non-urban settings and/or different regions of the country, variations of the mode (i.e., texting, online, in-person) included in the definition of sharing images, and differences in the types of behaviors captured when defining “sexting.” In the current study, we use a broad definition of “sexting”: “sending or showing someone sexual pictures of yourself where you were nude or nearly nude.”

Sexual relationships are normative, age-typical experiences for adolescents, and these relationships have significant implications for health, adjustment, and psychosocial functioning [11, 12]. Sexually curious behavior is reflective of typical sexual development during adolescence [13–15]. Sharing or posting sexual pictures may therefore be reflective of usual sexual expression in romantic relationships in adolescence. Alternatively, “sexting” may be a marker for involvement in a larger continuum of risky sexual behaviors. Certainly, “sexting” may also have a function in both of these arenas. In the current study, we examine how “sexting” is related to sexual behavior. We also examine how this behavior relates to psychosocial functioning, as this is less well understood. To examine whether potential differences in previous findings are perhaps related to age differences, correlates are examined for younger and older youth separately. As the first national study to examine these adolescent health outcomes, findings will inform how “sexting” falls into the larger rubric of adolescent sexual behavior in today’s digital age [16].

Methods

Data for the Teen Health and Technology (THT) Study were collected online between August 2010 and January 2011 from 5,907 13- to 18-year-olds in the United States (U.S.). The survey protocol was reviewed and approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board (IRB), the University of New Hampshire IRB, and GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network) Research Ethics Review Committee. A waiver of parental consent was granted to protect youth who would be potentially placed in harm’s way if their sexual orientation was unintentionally disclosed to their caregivers.

Participants were recruited from: (1) the Harris Poll Online (HPOL) opt-in panel (n=3989 respondents) and (2) through referrals from GLSEN (n=1918 respondents) to obtain an oversample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered youth. Because the focus in this paper is on the general population of adolescents, the current analyses are restricted to the HPOL sample. Members were recruited through a variety of methods, including targeted mailings, word of mouth, and online advertising. Panelists enrolled in the opt-in panel at the HPOL website, http://www.harrispollonline.com. HPOL members were randomly recruited for survey participation through email invitations that referred to a survey about their “online experiences.” The survey questionnaire was self-administered online. Qualified respondents were: (1) United States residents, (2) 13–18 years old, (3) in 5th grade or above, and (4) those who provided informed assent. The median survey length was 23 minutes.

Recent survey response rates are noticeably lower than in the past [17, 18]. The response rate for the HPOL sample was 7%. It was calculated as the number of individuals who started the survey divided by the number of email invitations sent, less any email invitations that were returned as undeliverable.

Measures

Sexting was defined as sexual photo-sharing through any mode. The behavior was queried based on a question developed by Lenhart and colleagues [10]: “In the past 12 months, how often have you sent or showed someone sexual pictures of yourself where you were nude or nearly nude? We are talking about times when you wanted to do these things. Please keep in mind that these things can happen anywhere including in-person, on the Internet, and on cell phones or text messaging.” Youth who responded positively were asked to indicate how the pictures were shared: in-person, by text message, online, or in some other way. Youth who had shared pictures online were asked follow-up questions about the most recent incident, including whether they knew the recipient offline and the age difference between the respondent and the recipient.

A range of sexual activities ever engaged in were also queried. Items 1, 2, 5, and 6 were modified from the Protecting the Next Generation project [19] and items 3 and 4 were created for this survey: (1) kissed or been kissed by someone romantically; (2) fondling (touching someone else’s body or someone else touching your body in a sexual way); (3) oral sex (stimulating the vagina or penis with the mouth or tongue); (4) sex with another person that involved a finger or sex toy going into the vagina or anus; (5) sex where a penis goes into a vagina (referred to here as “vaginal sex”); and (6) sex where a penis goes into an anus (referred to here as “anal sex”). All behaviors referred to “when you wanted to”, in order to distinguish between wanted and unwanted experiences.

Sexual risk behavior was queried for youth who reported having had vaginal and/or anal sex, including: number of past year sex partners, whether their most recent partner has ever had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), whether they talked about condoms before the first time they had sex, and general frequency of using a condom (1 [none of the time] – 5 [all of the time]).

Depressive symptomatology was measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-revised 10-item version for adolescents [20], social support with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [21], and past year substance use using measures from the Youth Risk Behavioral Survey [22]. Further detail is available upon request.

Weighting and identifying the final analytical sample

Data were weighted to known demographics of 13- to 18-year-olds based on the 2009 Current Population Survey [23], including biological sex, age, race/ethnicity, parents’ highest level of education, school location, and U.S. region. Next, a validity check was applied (i.e., survey response time less than five minutes; reporting one’s age at the beginning and end of the survey to be more than one year apart; and “straight lining,” providing the exact same response to each item in the last two grids of the survey); as a result, 69 participants were dropped. Youth who identified as transgender or gender non-conforming were excluded (n=62) because gender identity is likely related to “sexting” in ways that could not be examined within the scope of the current paper. Finally, missing responses (i.e., “don’t know”) on non-outcome variables (i.e., everything but the “sexting” indicators) were imputed using Stata version 11 statistical software’s “impute” command [24]. To avoid imputing truly non-responsive participants, respondents’ valid answers were required for at least 80% of the main variables; 143 respondents (4% of the 3,989) were dropped as a result. The final analytical sample was 3,715 youth.

Data analyses

First, differences in demographic characteristics were examined for youth who reported “sexting” versus youth who did not report “sexting” in the past year. Statistical significance was determined using F statistics, which are chi-square statistics that take the weighting scheme into account, for categorical data and linear regression for continuous data. Next, details of the most recent “sexting” incident were described for the overall sample, as well as by biological sex and age group (younger [13–15 years old] versus older [16–18 years old] youth). Differences were again tested for statistical significance, using F statistics for categorical data and linear regression for continuous data. Finally, rates of sexual behavior, risky sexual behaviors, and psychosocial indicators were examined for differences by past year “sexting” behavior by stratifying the sample by age group, as well as biological sex. Differences were quantified using logistic regression. Odds ratios were adjusted for demographic characteristics: youth age, biological sex, sexual identity, ethnicity, race, household income, region, being born again Christian (which may relate to sexual behavior [25]), school type (i.e., private, public, home schooled), and caregiver educational attainment.

Results

Seven percent (n=267) of youth 13–18 years of age reported “sexting” (sending or showing someone sexual pictures of themselves where they were nude or nearly nude) in the past year: 1% did so in-person, 5% by text message, 2% online, and 0.2% in some other way. Just over 1% (n=42) of youth reported “sexting” through more than one mode. Among youth under 18 years of age, 7% (n=212) admitted they sent or showed someone a sexual picture of themselves. The percentages by mode were similar to the overall sample.

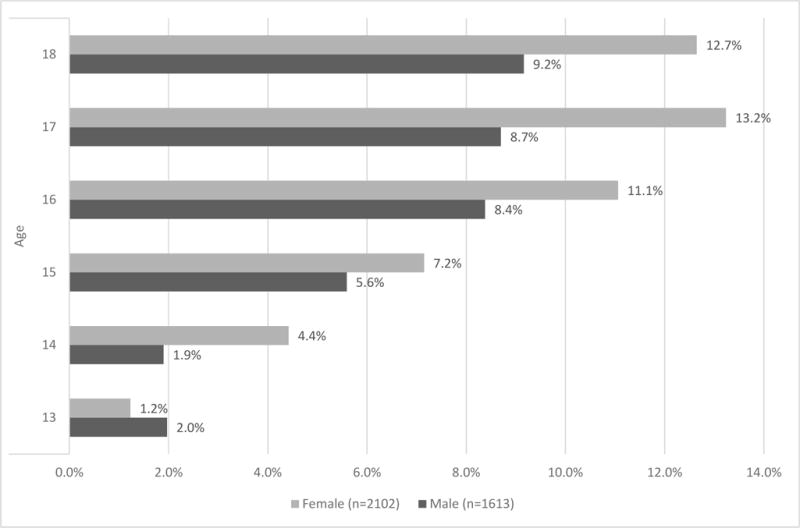

Females (9%) were significantly more likely than males (6%) to engage in “sexting” behavior (F(1, 3709)=8.4, p=0.004), although increasing age was associated with increasing rates of sending or showing sexual pictures for both sexes (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, male and female youth who sent or showed sexual pictures were significantly older and more likely to be Hispanic as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or other non-heterosexual identity (LGB). Males who sent or showed sexual photos were more likely to be living in a small town compared to males who did not send or show sexual pictures. Females who sent or showed sexual photos were less likely to be born again Christian. Aside from age and sexual identity, differences were not noted between youth who did and did not send or show sexy photos among younger youth (Table 2). Among older youth, those who sent or showed sexual photos were more likely to be female, Hispanic ethnicity, or LGB and were less likely to be born again Christian.

Figure 1.

Past year prevalence rates of “sexting” (online, via text messaging, and in-person) by age for males and females

Males: Design-based F(4.5, 7177.6) = 4.04, p=0.002

Females: Design-basd F(4.8, 9998.0) = 8.00, p<0.001

Table 1.

A comparison of demographic characteristics based upon involvement in “sexting” (online, via text messaging, and in-person) in the past year for male and female youth

| Demographic characteristics | Male youth (n=1613)

|

Female youth (n=2102)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No “sexting” (94%, n=1524) |

“Sexting” (6%, n=89) |

p-value | No “sexting” (91%, n=1924) |

“Sexting” (9%, n=178) |

p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Age | 15.4 (0.03) | 16.3 (0.17) | <0.001 | 15.6 (0.03) | 16.5 (0.10) | <0.001 |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 16.9 (137) | 30.5 (17) | 0.01 | 17.6 (211) | 24.5 (32) | 0.07 |

| Race | 0.39 | 0.33 | ||||

| White | 72.6 (1253) | 65.6 (66) | 66.2 (1367) | 59.7 (115) | ||

| Black/African American | 13.4 (99) | 20.1 (11) | 14.7 (235) | 17.9 (32) | ||

| All other | 14.0 (172) | 14.3 (12) | 19.1 (322) | 22.4 (31) | ||

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual or other non-heterosexual identity | 3.0 (41) | 11.5 (13) | <0.001 | 4.7 (86) | 13.9 (26) | <0.001 |

| Household income lower than average | 27.2 (349) | 24.7 (19) | 0.67 | 27.4 (455) | 32.5 (50) | 0.20 |

| Region | 0.02 | 0.42 | ||||

| Urban | 27.4 (405) | 42.0 (32) | 26.2 (530) | 29.9 (57) | ||

| Suburban | 33.7 (633) | 22.0 (28) | 30.4 (746) | 25.9 (58) | ||

| Small town | 38.9 (486) | 36.0 (29) | 43.4 (648) | 44.2 (63) | ||

| Born-again Christian | 27.7 (395) | 21.5 (16) | 0.34 | 28.7 (534) | 19.7 (35) | 0.02 |

| Type of school | 0.15 | 0.66 | ||||

| Public | 85.4 (1279) | 87.1 (78) | 87.8 (1651) | 90.8 (161) | ||

| Private | 8.5 (157) | 7.4 (8) | 7.1 (175) | 4.9 (10) | ||

| Home schooled | 4.9 (74) | 1.4 (1) | 3.7 (75) | 3.6 (6) | ||

| Not in school | 1.2 (14) | 4.1 (2) | 1.5 (23) | 0.8 (1) | ||

| Caregiver education attainment high school or less | 28.3 (295) | 32.4 (18) | 0.53 | 29.6 (391) | 32.5 (39) | 0.51 |

Table 2.

A comparison of demographic characteristics based upon involvement in “sexting” (online, via text messaging, and in-person) in the past year for younger and older youth

| Demographic characteristics | Younger youth (13–15 years old; n=1617)

|

Older youth (16–18 years old; n=2098)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No “sexting” (96%, n=1555) |

“Sexting” (4%, n=62) |

p-value | No “sexting” (89%, n=1893) |

“Sexting” (11%, n=205) |

p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Age | 14.0 (0.02) | 14.4 (0.1) | <0.001 | 17.0 (0.02) | 17.0 (0.07) | 0.56 |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| Female | 46.4 (813) | 55.7 (38) | 0.24 | 52.7 (1111) | 62.2 (140) | 0.03 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 17.8 (132) | 11.7 (6) | 0.28 | 16.7 (216) | 31.6 (43) | <0.001 |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual or other non-heterosexual identity | 3.0 (48) | 15.4 (11) | <0.001 | 4.6 (79) | 12.2 (28) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.85 | 0.08 | ||||

| White | 71.5 (1244) | 73.5 (52) | 67.5 (1376) | 58.5 (129) | ||

| Black/African American | 13.9 (117) | 15.2 (4) | 14.2 (217) | 19.9 (39) | ||

| All other | 14.6 (194) | 11.3 (6) | 18.3 (300) | 21.6 (37) | ||

| Household income lower than average | 25.6 (325) | 23.9 (16) | 0.78 | 28.9 (479) | 31.1 (53) | 0.58 |

| Region | 0.25 | 0.12 | ||||

| Urban | 25.3 (378) | 35.3 (17) | 28.3 (557) | 34.5 (72) | ||

| Suburban | 33.0 (652) | 24.5 (21) | 31.2 (727) | 24.3 (65) | ||

| Small town | 41.7 (525) | 40.2 (24) | 40.5 (609) | 41.2 (68) | ||

| Born-again Christian | 27.5 (410) | 28.4 (13) | 0.91 | 28.9 (519) | 18.0 (38) | 0.003 |

| Type of school | 0.71 | 0.64 | ||||

| Public | 86.9 (1310) | 90.2 (55) | 86.3 (1620) | 89.1 (184) | ||

| Private | 7.8 (156) | 4.0 (3) | 7.8 (176) | 6.4 (15) | ||

| Home schooled | 5.1 (86) | 5.8 (4) | 3.5 (63) | 1.8 (3) | ||

| Not in school | 0.2 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 2.4 (34) | 2.7 (3) | ||

| Caregiver education attainment high school or less | 27.5 (286) | 23.1 (10) | 0.61 | 30.3 (400) | 35.4 (47) | 0.23 |

Details of the most recent online incident

The 79 youth who reported sending or posting sexual photos online were asked follow-up questions about the recipient’s age and sex and whether the recipient was known offline. The majority of youth (69%: 76% of females and 62% of males) who sent or showed sexual pictures online did so with someone they knew offline. Ninety-five percent of female youth sent or showed sexual pictures to males; five percent to other females. In contrast, 26% of the males sent or showed sexual pictures to other males, and 74% to females. For both males and females, sexual identity predicted sending or showing a sexual photo to someone of the same sex: Seven of the nine males (66%) and two of the three females (68%) who sent sexual pictures to someone of the same sex were LGB youth.

Almost half (46%) of the recipients were same aged youth: 41% were older, 7% were younger, and 6% of respondents said they did not know what their age difference might be. Differences were noted by sex: more females (61%) than males (20%) sent or showed sexual pictures with someone older, whereas more males (10%) than females (1%) sent or showed sexual pictures to someone of unknown age (p=0.003). Among youth who sent or showed sexual pictures to different aged youth, 79% said the recipient was within four years of their own age. In all cases when the age differed by more than four years, the recipient was older, not younger. Differences, although non-significant due to small cell sizes, were noted by sex: among youth who sent or showed sexual pictures to someone older, 21% of females, compared to 2% of males, reported the recipient was more than four years older than them (p=0.40).

Relations between sending/showing sexual photos, sexual behavior, and risky sexual activity

Compared to 63% of youth who had ever had vaginal or anal sex, 14% of youth who had not had vaginal or anal sex sent or showed sexual photos of themselves in the past year (p<0.001). As shown in Tables 3 (by sex) and 4 (by age group), all sexual behaviors were associated with elevated odds of having sent or showed sexual photos of oneself in the past year among otherwise similar youth. For example, 51% of male youth who sent or showed sexual pictures had also had vaginal sex compared to 13% of males who did not (aOR = 5.6; 95% CI: 3.1, 10.1). Thirty-seven percent of younger youth who sent or showed sexual pictures reported having vaginal sex versus five percent of same age youth who did not (aOR = 7.7; 95% CI: 3.6, 16.3).

Table 3.

Associations between “sexting” (online, via text messaging, and in-person) and other sexual behaviors and psychosocial indicators for males and females

| Youth characteristics | Male youth (n=1613)

|

Female youth (n=2102)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No “sexting” (94%, n=1524) |

“Sexting” (6%, n=89) |

aOR | p-value | No “sexting” (91%, n=1924) |

“Sexting” (9%, n=178) |

aOR | p-value | |

| Sexual behaviors (past 12 months) | ||||||||

| Kissed | 45.6 (716) | 82.0 (71) | 5.1 (2.7, 9.5) | <0.001 | 45.4 (884) | 91.8 (160) | 11.0 (6.4, 18.9) | <0.001 |

| Fondled | 27.1 (428) | 78.9 (68) | 8.3 (4.2, 16.4) | <0.001 | 22.7 (462) | 83.0 (145) | 14.2 (9.1, 22.3) | <0.001 |

| Oral sex | 12.9 (207) | 52.0 (45) | 5.5 (3.1, 9.6) | <0.001 | 11.1 (216) | 70.7 (124) | 17.5 (11.5, 26.6) | <0.001 |

| Sex with a finger or toy | 11.4 (188) | 50.7 (45) | 6.6 (3.9, 11.0) | <0.001 | 11.7 (230) | 69.1 (124) | 14.7 (9.7, 22.5) | <0.001 |

| Vaginal sex | 13.0 (199) | 51.1 (41) | 5.6 (3.1, 10.1) | <0.001 | 13.0 (248) | 67.0 (115) | 11.4 (7.6, 17.0) | <0.001 |

| Anal sex | 2.7 (38) | 21.6 (15) | 7.5 (2.7, 20.4) | <0.001 | 2.1 (38) | 25.5 (41) | 10.8 (6.1, 19.2) | <0.001 |

| Risky sexual behaviorsa | ||||||||

| Use condoms most/all of the time | 75.1 (166) | 63.9 (26) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.5) | 0.30 | 68.3 (177) | 61.0 (65) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.18 |

| Most recent sex partner had an STI | ||||||||

| No | 61.9 (142) | 76.4 (32) | 1.0 (RG) | 67.0 (176) | 67.1 (79) | 1.0 (RG) | ||

| Yes | 1.8 (6) | 3.9 (3) | 2.9 (0.6, 14.5) | 0.19 | 4.5 (10) | 5.1 (6) | 1.1 (0.3, 4.6) | 0.85 |

| Don’t know | 36.3 (66) | 19.7 (10) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.01 | 28.5 (66) | 27.8 (31) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.7) | 0.87 |

| Talked about condoms before having sex with most recent sex partner | 63.9 (144) | 63.2 (29) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.87 | 70.5 (181) | 67.4 (76) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 0.62 |

| Had concurrent sex partners | 9.4 (21) | 23.4 (8) | 3.9 (1.3, 11.6) | 0.01 | 5.6 (14) | 10.6 (15) | 1.9 (0.8, 4.5) | 0.18 |

| Mean # of sex partners in the past year (M:SE) | 1.9 (0.4) | 3.5 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.03 | 1.4 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.4) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial indicators | ||||||||

| Depressive symptomatologyb | ||||||||

| Non-clinical | 96.2 (1474) | 91.0 (81) | 1.0 (RG) | 94.2 (1812) | 86.3 (157) | 1.0 (RG) | ||

| Mild | 3.0 (40) | 5.0 (4) | 1.5 (0.5, 5.0) | 0.47 | 3.6 (68) | 8.1 (13) | 2.4 (1.2, 4.8) | 0.01 |

| Major | 0.8 (10) | 4.0 (4) | 3.6 (0.4, 34.6) | 0.26 | 2.3 (44) | 5.6 (8) | 1.8 (0.6, 5.5) | 0.32 |

| High self-esteemb | 18.1 (268) | 4.4 (5) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.005 | 15.0 (299) | 5.2 (9) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.003 |

| High social supportb | 10.4 (169) | 14.2 (14) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.8) | 0.28 | 22.2 (437) | 24.6 (42) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 0.30 |

| Monthly use of alcohol | 8.5 (137) | 39.8 (31) | 5.4 (3.0, 9.5) | <0.001 | 7.7 (146) | 20.8 (41) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.6) | 0.001 |

| Monthly use of marijuana | 5.2 (78) | 33.0 (23) | 8.7 (4.3, 17.3) | <0.001 | 4.2 (79) | 13.4 (27) | 2.8 (1.6, 5.0) | <0.001 |

Among the 259 male youth and 368 female youth who reported having vaginal or anal sex

Major depressive symptomatology = 5 or more symptoms of depression nearly every day for the past two weeks, one of which is anhedonia or dysphoria, as well as interference in school work; family relationships, and/or friend relationships; Mild depressive symptomatology = 3 or more symptoms nearly every day for the past two weeks; Non-clinical = all other youth. High self-esteem = a score one standard deviation or greater above the sample mean (i.e., 49 and above). High social support = a score one standard deviation or greater above the sample mean (i.e., 27 and above).

aOR = Odds Ratio adjusted for demographic characteristics (youth age, biological sex, sexual identity, ethnicity, race, household income, region, born again Christian, school type, and caregiver educational attainment)

RG = Reference group

Table 4.

Associations between “sexting” (online, via text messaging, and in-person) and other sexual behaviors and psychosocial indicators for younger and older youth

| Younger youth (n=1617)

|

Older youth (n=2098)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth characteristics | No “sexting” (96%, n=1577) |

“Sexting” (4%, n=63) |

aOR (95% CI) | p-value | No “sexting” (89%, n=1924) |

“Sexting” (11%, n=213) |

aOR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Sexual behaviors (past 12 months) | ||||||||

| Kissed | 34.7 (534) | 78.5 (48) | 5.3 (2.7, 10.4) | <0.001 | 55.9 (1066) | 90.8 (183) | 7.9 (4.8, 13.0) | <0.001 |

| Fondled | 13.9 (226) | 62.9 (39) | 7.7 (4.0, 14.7) | <0.001 | 35.5 (664) | 87.1 (174) | 11.4 (7.3, 17.8) | <0.001 |

| Oral sex | 5.5 (86) | 36.6 (21) | 7.5 (3.3, 17.2) | <0.001 | 18.2 (337) | 71.7 (148) | 11.2 (7.6, 16.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex with a finger or toy | 5.2 (83) | 35.0 (25) | 7.5 (3.8, 14.9) | <0.001 | 17.7 (335) | 70.2 (144) | 10.0 (6.9, 14.6) | <0.001 |

| Vaginal sex | 5.3 (74) | 36.6 (21) | 7.7 (3.6, 16.3) | <0.001 | 20.3 (373) | 68.2 (135) | 8.0 (5.6, 11.5) | <0.001 |

| Anal sex | 1.4 (20) | 17.1 (7) | 10.1 (2.5, 41.2) | 0.001 | 3.4 (56) | 26.1 (49) | 8.3 (5.0, 13.7) | <0.001 |

| Risky sexual behaviorsa | ||||||||

| Use condoms most/all of the time | 71.4 (59) | 56.7 (10) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.03 | 72.0 (284) | 62.9 (81) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.21 |

| Most recent sex partner had an STI | ||||||||

| No | 50.9 (48) | 73.5 (14) | 1.0 (RG) | 68.0 (270) | 69.8 (97) | 1.0 (RG) | ||

| Yes | 1.9 (3) | 2.7 (1) | 1.7 (0.2, 14.3) | 0.61 | 3.4 (13) | 5.1 (8) | 1.3 (0.4, 4.1) | 0.7 |

| Don’t know | 47.2 (32) | 23.8 (7) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.8) | 0.29 | 28.6 (100) | 25.2 (34) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | 0.37 |

| Talked about condoms before having sex with most recent sex partner | 54.8 (49) | 50.5 (13) | 0.6 (0.2, 2.2) | 0.48 | 70.5 (276) | 68.6 (92) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.96 |

| Had concurrent sex partners | 11.1 (9) | 31.0 (4) | 3.7 (0.9, 15.7) | 0.07 | 6.6 (26) | 12.4 (19) | 2.3 (1.1, 4.8) | 0.03 |

| Mean # of sex partners in the past year (M:SE) | 2.6 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 0.47 | 1.4 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.5) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial indicators | ||||||||

| Depressive symptomatologyb | ||||||||

| Non-clinical | 96.3 (1496) | 89.1 (55) | 1.0 (RG) | 94.1 (1790) | 87.8 (183) | 1.0 (RG) | ||

| Mild | 2.6 (40) | 6.3 (4) | 2.4 (0.7, 7.8) | 0.16 | 3.9 (68) | 7.1 (13) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.4) | 0.11 |

| Major | 1.1 (19) | 4.6 (3) | 4.4 (0.7, 26.6) | 0.11 | 2.0 (35) | 5.1 (9) | 1.9 (0.7, 5.3) | 0.247 |

| High self-esteemb | 17.8 (261) | 0.0 (0) | NC | 15.4 (306) | 6.4 (14) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.005 | |

| High social supportb | 15.4 (267) | 26.2 (16) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.5) | 0.04 | 17.1 (339) | 18.7 (40) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 0.40 |

| Monthly use of alcohol | 3.9 (64) | 24.6 (16) | 6.1 (2.9, 12.9) | <0.001 | 12.2 (219) | 29.4 (56) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.9) | <0.001 |

| Monthly use of marijuana | 3.0 (47) | 27.9 (13) | 10.3 (4.4, 24.0) | <0.001 | 6.3 (110) | 19.0 (37) | 3.1 (1.9, 5.1) | <0.001 |

Among the 105 younger youth and 522 older youth who reported having vaginal or anal sex

Major depressive symptomatology = 5 or more symptoms of depression nearly every day for the past two weeks, one of which is anhedonia or dysphoria, as well as interference in school work; family relationships, and/or friend relationships; Mild depressive symptomatology = 3 or more symptoms nearly every day for the past two weeks; Non-clinical = all other youth. High self-esteem = a score one standard deviation or greater above the sample mean (i.e., 49 and above). High social support = a score one standard deviation or greater above the sample mean (i.e., 27 and above).

aOR = Odds Ratio adjusted for demographic characteristics (youth age, biological sex, sexual identity ethnicity, race, household income, region, born again Christian, school type, and caregiver educational attainment)

RG = Reference group

NC = Not calculable

For male (Table 3), and older and younger (Table 4) youth, having versus not having concurrent sexual partners during one’s most recent sexual relationship was associated with elevated odds of sending or showing sexual pictures among otherwise demographically similar youth. For male and female youth (Table 3) as well as older youth (Table 4), the relative odds of “sexting” also increased incrementally with each additional past-year sexual partner that youth reported, after adjusting for demographic characteristics. Among otherwise demographically similar males, lower odds of “sexting” were also associated with not knowing their sexual partner’s STI history.

Relations between sharing sexual photos and psychosocial characteristics

Among demographically similar youth, psychosocial problems were indicated more frequently for youth who sent or showed sexual photos of themselves, compared to youth who did not (Tables 3 and 4). For all youth, high self-esteem was negatively associated, whereas alcohol and marijuana use were positively associated, with having sent or showed sexual pictures. For female youth, depressive symptomatology was additionally associated with elevated odds of having sent or showed sexual pictures of herself. Similar but non-significant trends of depressive symptomatology were also noted for younger youth. Additionally, for younger youth, high social support was associated with decreased odds of having sent or showed sexual photos of themselves.

Discussion

Among 13- to 18-year-olds surveyed in the national Teen Health and Technology Study, “sexting” is uncommon. Fewer than one in ten youth sent or showed sexual photos of themselves online, via text messaging, or in-person in the past year. Text messaging is the most common mode used to share sexual photos: half as many report sending or sharing sexual photos online, and half as many again, in-person. While perhaps not a new behavior (à la the Polaroid pictures of old), sharing sexual photos is predominately technology-driven for adolescents in today’s digital world. Given how atypical it is to engage in “sexting” behaviors however, the data suggest that technology access is a less important factor than what is going on in the adolescent’s life: Youth who send and show sexual photos of themselves are much more likely to be using substances [26] and less likely to have high self-esteem. They also are much more likely to be engaging in sexual behaviors as well some risky sexual behaviors, particularly having concurrent sex partners for male youth, as well as older and younger youth, and increasing numbers of past year sexual partners for male and female youth, as well as older youth. Thus, “sexting” appears to be related to a more general cluster of behaviors indicative of psychosocial challenge and risky sexual behavior.

Not all youth who send and share sexual photos are necessarily engaging in problematic behavior. For some teens, taking and sending sexual pictures of themselves plays a role in a healthy sexual relationship. Among a sample of “sexting” cases brought to police attention, one-third were considered experimental and reflective of sharing images for the purposes of romance or sexual attention-seeking [27]. In qualitative work with adolescents, Lenhart and colleagues noted that many young people talked about “sexting” as a way to initiate romantic relationships or used in place of having sex [10]. Certainly, from a public health perspective, the risk of sexually transmitted infections is lower for couples who are sharing sexual photos of themselves in place of vaginal or anal sex.

In the current study, almost all youth who share sexual photos of themselves with someone of the same sex self-identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB). Perhaps LGB youth are sharing sexual photos as a way to create intimacy in the absence of being able to be publicly intimate with their romantic partner. Understanding the motivations behind “sexting” is critical for parents, teachers, police, and pediatricians who are trying to determine how to handle such situations as they arise. Future research could examine how these findings translate to other minority youth, such as transgender youth, as this is critical to ensure a comprehensive understanding of “sexting” behavior across adolescents.

Although females are more likely than males and older youth more likely than younger youth to share sexual photos, the profile of psychosocial challenge and sexual risk taking behavior is remarkably similar for all youth. Thus, while the likelihood of sharing sexual photos varies by biological sex and age, the characteristics of these youth are otherwise similar. Extensive tailoring of prevention efforts does not appear warranted.

Some interesting details about “sexting” recipients are also noted. Although the majority of youth who share sexual pictures online did so with recipients they knew offline, almost one in three youth share pictures with recipients they know online but not in-person. Much of the research attention to date has focused on exchanges between friends or romantic partners [10]. Little is known about the motivations and nuanced experiences of exchanges between people only known online. Perhaps this is an opportunity for some youth to explore their sexuality in ways that they are not comfortable doing with people they know. Whether this leads to further sexual exploration and perhaps risky sexual behavior offline may be an important future inquiry.

Among youth who shared or sent a picture online, two in five intended recipients are at least one year older than the respondent. Of those who report an older recipient, one in five indicate that the person is more than four years older. Aggravated “sexting” incidents involving adults represent an estimated one in three of aggravated cases [27]. Such cases that come to police attention typically involve adult offenders who have developed relationships and seduced victims. Without further information, it is unclear whether the situations in the current study involve criminal elements or not. Age differentials between the sender and recipient seem to be a particularly important aspect of the situation that could contextualize whether the behavior is a marker for greater cause for concern and thus in need of a more systematic intervention. However, the sub-samples are not large enough in the current sample to examine this further.

Consensus about the definition and therefore optimal measurement of “sexting” is lacking. Based upon previous work [10], the current study defines the behavior as sending “nude or nearly nude” pictures. This could represent a broad range of behaviors, ranging from being in a revealing bathing suit or shirtless to being completely nude. Mitchell and colleagues used a similar definition and then asked a follow-up question about whether the picture was sexually explicit (i.e., showing naked breasts, genitals, or bottoms) [9]. This narrower definition cut the rate by more than half: 2.5% of 10- to 17-year-olds endorsed the broader definition, whereas 1% endorsed the narrower definition. Importantly, even with this relatively broad definition, uniformly low rates of “sexting” are noted across these three national studies.

Limitations

Because the data are cross-sectional, directionality cannot be determined. For example, youth may experience depressive symptomatology as a result of this broader pattern of sexual risk behavior or as a result of knowing a sexual picture of them is “out;” or youth with depressive symptomatology may be more inclined to engage in “sexting”. Also, sexual pictures that include one being “nude or nearly nude” reflects a range of pictures, from youth engaging in sexual acts to adolescent females posing in bathing suits to “flash” the camera[9]. The degree of sexual explicitness in the photos may possibly relate to different odds of negative consequences or harmful impact. Certainly too, sexual behavior can be sensitive to discuss and youth may under-report their engagement with these behaviors.

Implications

While the media has portrayed “sexting” as a problem caused by new technology, parents and health professionals may be more effective by approaching it as an aspect of adolescent sexual development and exploration and, in some cases, risk-taking [5]. For youth engaging in risky behaviors across multiple environments, a comprehensive, multi-system approach that broadly targets risky behaviors may be more effective than responding to “sexting” incidents with lectures or punishments. Correspondingly, prevention focusing specifically on “sexting” may be less effective than efforts to incorporate information on “sexting,” such as the potential consequences and risks and how to handle requests for sexual pictures into established and proven sex education, sexual harassment, and other social/emotional-learning programs [28–30].

Implications and contribution.

In a national survey of 13- to 18-year-olds, “sexting” online, via text messaging, and in-person is positively associated with risky sexual behavior and substance use and negatively associated with high self-esteem. Findings suggest that “sexting” is reflective of adolescent sexual development and exploration and, in some cases, risk-taking and psychosocial challenge.

Acknowledgments

We thank the entire study team from the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, the University of New Hampshire, the Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network (GLSEN), Latrobe University, and Harris Interactive, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. And, we thank the study participants for their time and willingness to participate in this study.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by Award Number R01 HD057191 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Abbreviations

- GLSEN

Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network

- HPOL

Harris Poll Online

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- THT

Teen Health and Technology

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Michele L. Ybarra, Center for Innovative Public Health Research.

Kimberly J. Mitchell, Crimes against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire.

References

- 1.Judge A. “Sexting” among U.S. adolescents: psychological and legal perspectives. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20:86–96. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.677360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leary M. Self produced child pornography: The appropriate societal response to juvenile self-sexual exploitation. Va J Soc Policy Law. 2008;15:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, et al. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:828–833. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, et al. Sexually explicit cell phone messaging associated with sexual risk among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:667–673. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, et al. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, et al. Sexting among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson C. Sexting behaviors among young Hispanic women: incidence and association with other high-risk sexual behaviors. Psychiatr Q. 2011;82:239–243. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klettke B, Hallford DJ, Mellor DJ. Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: A national study. Pediatrics. 2012;129:13–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenhart A. Teens and sexting. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2009. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Teens-and-Sexting.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2003;13:1–24. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1301001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchey HA, Furman W. Dating and romantic experiences in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponton LE, Judice S. Typical adolescent sexual development. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2004;13:497–511. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen AC. Adolescent development. Annu Rev Psychol. 1988;39:583–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.39.1.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, Moilanen K. Adolescent sexuality: Behavior and meaning. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis DA, Frintner MP, Mulligan DA, et al. Media education in pediatric residencies: a national survey. Acad Pediatr. 2012;13:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell KJ, Jones LM. Youth Internet Safety (YISS) Study: Methodology report. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire; 2011. Available at: http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/YISS_Methods_Report_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, et al. Social media and young adults. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2010. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttmacher Institute. Adolescent Questionnaire. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2004. Protecting the Next Generation: National Survey of Adolescents. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/PNG-surveys/Uganda2004_Adolescent.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haroz EE, Ybarra ML, Eaton WW. Psychometric evaluation of a self-report scale to measure adolescent depression: the CESDR-10 in two representative adolescent samples in the United States. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2005. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2005. 2006;55:1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States’ Census Bureau. Current Population Survey: population estimates, vintage 2009, national tables. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/2000s/vintage_2009/index.html. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- 24.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM, Shearer CL, et al. Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. J Sex Res. 2004;41:150–159. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Temple JR, Le VD, van den Berg P, et al. Brief report: Teen sexting and psychosocial health. J Adolesc. 2014;37:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ. How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics. 2012;129:4–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ott M, Rouse M, Resseguie J, et al. Community-level successes and challenges to implementing adolescent sex education programs. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0574-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinton-Sherrod AM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Gibbs D, et al. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of four school-based sexual violence interventions. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:19S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908319593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gullotta TP, Bloom M, Gullotta CF, et al., editors. A blueprint for promoting academic and social competence in after-school programs. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2009. [Google Scholar]