Abstract

Background: The skeletal phenotype of mucopolysaccharidosis VI (MPS VI) is characterized by short stature and growth failure.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to construct reference growth curves for MPS VI patients with rapidly and slowly progressive disease.

Methods: We pooled cross-sectional and longitudinal height for age data from galsulfase (Naglazyme®, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.), treatment naïve patients (n = 269) who participated in various MPS VI studies, including galsulfase clinical trials and their extension programs, the MPS VI clinical surveillance program (CSP), and the MPS VI survey and resurvey studies, to construct growth charts for the MPS VI population. There were 229 patients included in this study, of which data from 207 patients ≤25 years of age with 513 height measurements were used for constructing reference growth curves.

Results: Height for age growth curves for the 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles were constructed for patients with rapidly and slowly progressing disease defined by the pre-enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) uGAG levels of > or ≤200 μg/mg creatinine. The mean (SD) pre-ERT uGAG levels were 481.0 (218.6) and 97.8 (56.3) μg/mg creatinine for the patients ≤25 years of age with rapidly (n = 131) and slowly (n = 76) progressing MPS VI disease, respectively. The median growth curves for patients with ≤ and >200 μg/mg creatinine were above and below the median (50th percentile) growth curve for the entire MPS VI population.

Conclusion: MPS VI growth charts have been developed to assist in the clinical management of MPS VI patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this chapter (doi:10.1007/8904_2014_333) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

The skeletal phenotype of mucopolysaccharidosis VI (MPS VI; OMIM: 253200), a rare lysosomal storage disorder, is characterized by short stature, growth failure, and dysostosis multiplex (Neufeld et al. 2013). Dysostosis multiplex involves severe abnormalities in the development of skeletal cartilage and bone and is a characteristic of all MPS disorders except MPS III (Lachman et al. 2010). Accelerated growth with advanced bone maturation has been reported during the first year of life in MPS VI infants, which is followed by a deceleration and growth failure after the 2nd year of life, and delayed onset and progression of puberty (Heron et al. 2004; Scarpa et al. 2009; Decker et al. 2010). The adult height (range 110–140 cm) of most MPS VI patients is below −2 SD of the reference growth curves from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) growth charts for normal age-adjusted peers (Neufeld et al. 2013; Kuczmarski et al. 2002). The CDC provides data from the normal population from which height Z-scores can be calculated based on age and gender. These CDC curves refer specifically to the normal population. The rationale for generating MPS VI-specific curves is to be able to judge the normality of growth for this unique population. MPS VI patients exhibit severe and continuous deceleration in growth compared to the growth rates exhibited in the normal population as portrayed in the CDC growth charts, thus limiting the value of using the CDC growth charts to readily interpret and follow growth of MPS VI patients over time. Reference growth charts for the MPS VI population are currently not available.

Disease-specific growth charts are valuable tools to clinicians for tracking growth as deviations from what is considered normal for that patient population and can alert them of secondary problems such as malnutrition, endocrine abnormality, or psychosocial deprivation (Ranke 1989). In addition, disease-specific growth charts are valuable for counseling parents in regard to expected growth or developmental milestones (Ranke 1989). While disease-specific growth charts are available for several other syndromes where short stature is a common feature (Hall et al. 2012), these references cannot be used as a guide for MPS VI patients because of dissimilar growth patterns (Horton et al. 1982; Tomatsu et al. 2012). Specific growth charts are needed for MPS VI patients with either rapidly or slowly progressive disease (as defined in Methods section (Swiedler et al. 2005)) to assist clinicians in managing their development.

Methods

Data Source for Integrated Height Analysis

We pooled cross-sectional and longitudinal height for age data from patients who participated in the MPS VI cross-sectional Survey Study done in 2001–2002 (Swiedler et al. 2005); clinical trials and their extension programs, including phase 1/2, phase 2, phase 3 (Harmatz et al. 2004; Harmatz et al. 2005; Harmatz et al. 2006; Harmatz et al. 2008), and a phase 4 study (Harmatz et al. 2013); the MPS VI clinical surveillance program (CSP; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00214773); and the Resurvey Study (Giugliani et al. 2014) to construct growth charts for patients with the MPS VI disorder. Patients treated with galsulfase (recombinant human arylsulfatase B; rhASB; Naglazyme®; an enzyme replacement therapy [ERT] for MPS VI) or patients status post hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) were excluded from this analysis. The number of patients in the above mentioned studies that contributed height data for the development of the growth charts is listed in Table 1. Because patients may have participated in more than one MPS VI study, duplicate entries were identified in order to determine a unique dataset for the patients (n = 269). All height measurements included in the integrated dataset were from ERT or HSCT treatment naïve patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MPS VI patients included in the studya,b,c

| Group | Parameter | All ages | Age 2–18 years | Age ≤25 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | n Patients | 229 | 168 | 207 | |

| Males | n (%) | 112 (49) | 79 (47) | 100 (48) | |

| Females | n (%) | 117 (51) | 89 (53) | 107 (52) | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 12.7 (9.6) | 9.5 (4.2) | 10.4 (5.9) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 10.2 (6.1, 16.5) | 8.9 (6.0, 13.2) | 9.2 (5.7, 15.0) | ||

| Range | 0.0, 56.2 | 2.0, 17.8 | 0.0, 25.0 | ||

| uGAG | Mean (SD) | 313.2 (257.9) | 347.1 (216.8) | 340.3 (256.1) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 289.5 (94.0, 466.7) | 343.7 (172.4, 485.7) | 323.6 (131.0, 488.5) | ||

| Range | 0.0, 1491.3 | 0.0, 1292.4 | 0.0, 1491.3 | ||

| n Height Measurementsd | 558 | 396 | 513 | ||

| Height (cm) | Mean (SD) | 112.1 (26.6) | 105.9 (19.8) | 107.9 (24.0) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 103.0 (93.3, 132.4) | 99.5 (93.0, 112.1) | 100.0 (92.2, 122.0) | ||

| Range | 49.8, 182.9 | 80.0, 182.9 | 49.8, 182.9 | ||

| Low uGAG | n Patients | 97 | 51 | 76 | |

| uGAG | Mean (SD) | 87.4 (56.5) | 107.1 (55.6) | 97.8 (56.3) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 68.6 (42.0, 134.7) | 102.1 (65.0, 154.1) | 92.7 (51.7, 144.4) | ||

| Range | 0.0, 199.3 | 0.0, 199.3 | 0.0, 199.3 | ||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 17.7 (11.7) | 10.2 (4.7) | 12.9 (6.7) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 15.7 (8.7, 23.4) | 10.2 (5.8, 14.7) | 14.2 (6.1, 18.8) | ||

| Range | 0.0, 56.2 | 2.7, 17.2 | 0.0, 25.0 | ||

| Height (cm) | Mean (SD) | 132.3 (27.0) | 121.6 (25.6) | 126.2 (27.2) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 140.5 (113.5, 152.6) | 119.8 (99.5, 142.6) | 127.5 (106.5, 150.0) | ||

| Range | 57.9, 182.9 | 81.5, 182.9 | 57.9, 182.9 | ||

| High uGAG | n Patients | 132 | 117 | 131 | |

| uGAG | Mean (SD) | 479.1 (218.9) | 451.7 (173.1) | 481.0 (218.6) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 437.9 (338.9, 547.8) | 419.2 (336.8, 531.4) | 438.7 (340.9, 549.3) | ||

| Range | 202.0, 1491.3 | 202.0, 1,292.4 | 202.0, 1,491.3 | ||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 9.0 (5.2) | 9.3 (4.0) | 8.9 (4.9) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.3 (5.4, 12.0) | 8.5 (6.3, 12.0) | 8.2 (5.4, 12.0) | ||

| Range | 0.1, 29.8 | 2.0, 17.8 | 0.1, 22.4 | ||

| Height (cm) | Mean (SD) | 97.4 (13.3) | 99.0, 11.3 | 97.3 (13.4) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 97.3 (90.0, 103.7) | 98.0 (92.2, 104.2) | 97.0 (90.0, 103.8) | ||

| Range | 49.8, 159.0 | 80.0, 159.0 | 49.8, 159.0 |

aThe baseline characteristics were calculated from data collected at study baseline, ie, first baseline. All patients had both pre-ERT uGAG levels and pre-ERT (or within 1 month of ERT) height measurements

bLow and high uGAG refers to pre-ERT uGAG levels of ≤ or >200 μg/mg creatinine, respectively

cHeight in cm refers to height at enrollment

dTotal number of height measurements include all pre-ERT visits from patients who also had pre-ERT uGAG values available

Definitions of Slowly and Rapidly Progressive Disease

Patients with rapidly or slowly progressive disease were defined by the pre-ERT urinary glycosaminoglycan (uGAG) levels of > or ≤200 μg/mg creatinine, respectively (Swiedler et al. 2005). High uGAG levels (>200 μg/mg creatinine) have been reported to be associated with age-adjusted short stature, reduced joint range of motion, compromised pulmonary function, and impaired endurance as measured by the 6-minute walk test. Low uGAG levels (≤200 μg/mg creatinine) have been reported to be associated with later onset of typical symptoms with less pronounced growth retardation. The pre-ERT uGAG values were obtained from 2 sources: (1) the uGAG measurements of ERT-naïve patients, such as those in the placebo arm of clinical trials and the cross-sectional Survey Study, and (2) the measurements made prior to the initiation of ERT on ERT-treated patients in all studies. When more than one pre-ERT uGAG measurement was available, an average of all values was used for determination of rapidly or slowly progressive disease.

The height data included all height measurements for age for ERT-naïve patients as well as measurements from ERT patients prior to or within one month of the first ERT infusion.

Laboratory Assessments

Urinary GAG levels were determined by spectrophotometric detection of metachromatic change in the 1,9-dimethyl-methylene blue (DMMB) dye upon GAG binding (Whitley et al. 1989) (performed at BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. labs). Urinary GAG levels were measured on the first morning voided samples and normalized for urine creatinine levels.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were conducted with PC-SAS 9.3 (TS Level 1 M1) software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Lambda Mu Sigma (LMS) Chartmaker Pro, Version 2.54 (the Institute of Child Health, London). Demographic information was obtained on patients’ pre-ERT and summarized using descriptive statistics, including the following parameters: age, gender, pre-ERT uGAG, height, and the associated characteristic collected with that measurement (e.g., height by pre-ERT uGAG group). Height by age was plotted by uGAG categories, ≤200 and >200 μg/mg creatinine.

Height measurements were taken as standing height as per the center’s procedure for height measurement. Height for age data from patients who provided both pre-ERT uGAG measurement and pre-ERT (or within 1 month of ERT) height measurement(s) was included in the analyses for construction of MPS VI reference growth curves using the LMS method (Cole and Green 1992). The distribution of height measurements as a function of age (covariate) is summarized by 3 curves representing the following parameters: skewness (Lambda, L), median (Mu, M), and the generalized coefficient of variation (Sigma, S). For the LMS procedure, the method of maximum penalized likelihood was used to generate reference percentile curves for MPS VI. Schwarz Bayesian Criteria (SBC) was used for the model selection. Many patients provided multiple height measurements; however, the LMS method allowed for statistical assignment of equal weight per patient regardless of the number of measurements leading to robust calculations of reference growth curves. The final L, M, and S parameters and percentile data are shown in Supplement Tables 1–3. These age-specific L, M, and S parameters can be used to calculate z-score height of an individual child at any given age using a simple formula (height of child /M)L – 1(L/S)) (Cole 1989).

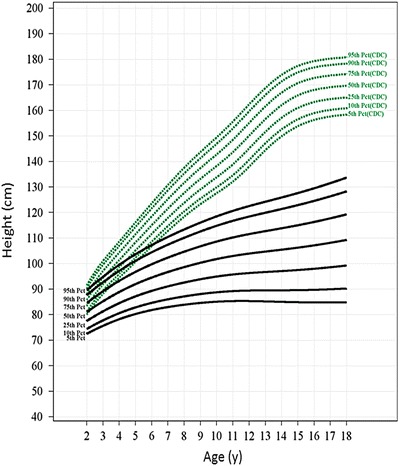

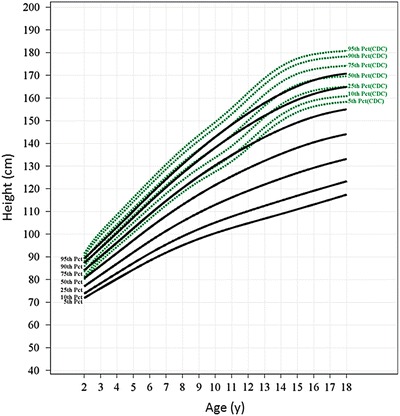

Reference height for age curves for the 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles was constructed for patients with rapidly and slowly progressive disease as defined by the pre-ERT uGAG level. Data were plotted for comparison purposes with the normative 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles using the CDC’s national growth data. The LMS Z-scores graphs were generated for patients with rapidly and slowly progressive disease, respectively.

The growth curves in this report represent ages 2–18 years; however, height data from patients ≤25 years of age was used in the growth modeling to attenuate flaring “right edge effect” of data truncation on statistical smoothing as previously described (Tarquinio et al. 2010). The growth curves in this report exclude 0–2 years of age due to a small sample size for this age range (Supplement Table 4) and the limitations of the methodology used for this age group.

Results

Demographics

Of the unique set of 269 patients identified across various MPS VI studies, pre-ERT uGAG and pre-ERT (or within 1 month of ERT) height measurements were available for 229 patients with 558 height measurements (Table 1). Both male and female patients were nearly equally represented in this dataset. The mean (SD) age of all patients was 12.7 (9.6) years and the mean (SD) height was 112.1 (26.6) cm (Table 1). Of the 229 patients, height for age data from patients ≤25 years of age (n = 207) (total height measurements = 513) was included for the construction of the MPS VI growth charts. The number of height measurements per patient ranged from 1 to 41 (median: 1) with a mean (SD) of 1.5 (1.4) to 2.7 (6.9) data points across various age ranges (Supplement Table 4).

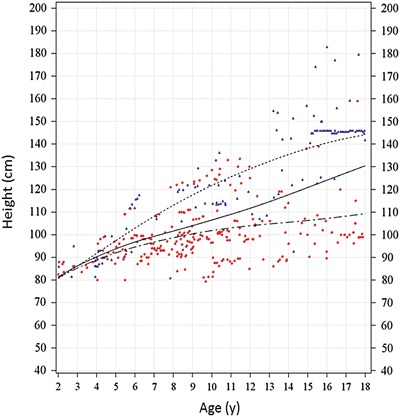

MPS VI Growth Curves

Height data for ages 0–25 years were used to generate growth curves; however, the growth curves are displayed for the age range of 2–18 years as discussed in methods. Figure 1 shows the height for age of patients 2–18 years of age. The estimated median height of the overall population showed a significant increase from 81.4 cm at age 2 to 130.5 cm at age 18 (Fig. 1).The heights of MPS VI patients as shown in Fig. 1 scatterplot were heterogeneous; therefore, we used the LMS procedure to transform the height for age data into normal distribution and smooth the resultant curves as described in the methods.

Fig. 1.

Height for age scatterplot for MPS VI patients 2–18 years of age. Height for age individual measurements for patients 2–18 years of age is plotted using color-coded symbols per pre-ERT uGAG levels (red circles for high and blue triangles for low pre-ERT uGAG levels). The LMS-generated smoothened growth curves for rapidly progressing (dotted-dash), slowly progressing (dotted), and whole population (solid line) are shown. The L, M, and S parameters for generating these smoothened curves are shown in Supplement Tables 1–3. Many patients provided multiple height measurements as shown in this figure; however, LMS method allowed for statistical assignment of equal weight per patient regardless of the number of measurements leading to robust calculations of reference growth curves. The growth curve for the slowly progressing population continued on a positive trajectory between ages 18 - 25 years likely due to distribution of patients with taller heights in this subgroup containing largely cross-sectional data (not shown). The positive slope of the growth curve for slowly progressing patients (ages 18–25 years) also skewed the overall growth curve for MPS VI (not shown). Thus, in the absence of a larger dataset (including longitudinal data) for this age range, the growth curves were truncated at age 18 years. Further, heights of MPS VI patients increase by <1 cm after age 18 years (Giugliani et al. 2014)

There were limited differences in the height for age curves for male and female MPS VI individuals (Supplement Fig. 1). Therefore, we combined data from the male and female patients to create more robust reference growth charts as shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 3.

Fig. 2.

Growth charts for the rapidly progressing MPS VI population. The 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentile reference growth curves for the rapidly progressing population (black) ages 2–18 years are shown along with the 5th to 95th CDC reference curves for normal population (green). CDC curves were recreated from data from the CDC website using mean heights of males and females at each age point. The L, M, and S parameters used for generating reference curves for rapidly progressing patients and the percentile values are shown in Supplement Table 2

Fig. 3.

Growth charts for the slowly progressing MPS VI population. The 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentile reference growth curves for the slowly progressing population (black) aging 2–18 years are shown along with the 5th to 95th CDC reference curves for normal population (green). The L, M, and S parameters used for generating reference curves for rapidly progressing patients and the percentile values are shown in Supplement Table 3

Growth of Rapidly and Slowly Progressing MPS VI Patients

The patients were further stratified as rapidly and slowly progressive patients based on the pre-ERT uGAG levels as defined in the methods. The mean (SD) pre-ERT uGAG levels were 481.0 (218.6) μg/mg creatinine for the rapidly progressive (n = 131) and 97.8 (56.3) μg/mg creatinine for the slowly progressive (n = 76) patients ≤25 years of age (Table I).

The slowly progressing ≤25 years of age patient group had higher age-adjusted mean (SD) heights compared to the rapidly progressing group (126.2 [27.2] vs. 97.3 [13.4] cm; Table 1 and Fig. 1). The difference between the two groups progressively increased after age 4–5 years (Fig. 1). The estimated median height of the slowly progressing group continued to increase during the teenage years (estimated median height at age 18 = 144.1 cm; Fig. 1). On the other hand, the estimated median height of the rapidly progressing patients showed a much slower but gradual increase in height past age 10–12 years, increasing to 109.3 cm by age 18 years (Fig. 1).

MPS VI Growth Charts and Z-Scores for Rapidly and Slowly Progressing MPS VI Patients

Figures 2 and 3 show reference growth curves for rapidly and slowly progressive patients, respectively, for 7 percentiles (5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th) along with the CDC reference percentiles for normal peers. The growth of rapidly progressing patients followed a slower but continuous trajectory during the teen years (Fig. 2), whereas the 50th percentile of slowly progressing patients followed a growth trajectory below and nearly parallel to the 5th percentile of the normative CDC curve (Fig. 3). The 90th percentile of slowly progressing patients had heights comparable to the 25th percentile of the normative CDC curves by late teen years.

The LMS method also allowed for Z-score calculation. Based on the growth charts developed for rapidly and slowly progressing patients, the Z-scores were distributed between +2 SD and −2 SD for the respective groups (Supplement Figs. 2 and 3).

Discussion

We collected pre-ERT (or within 1 month of ERT) height measurements from the largest cohort of MPS VI patients, to date, to construct growth charts for the MPS VI population. The 207 patients ≤25 years of age with available pre-ERT (or within 1 month of ERT) height measurements represent approximately 19% of the estimated worldwide MPS VI population (Swiedler et al. 2005); however, these numbers are an underestimation of the true prevalence as the referenced numbers are based on the estimates from the USA, Europe, and Brazil. The patient population in this dataset included patients from many countries and, thus, supports wide applicability of these MPS VI growth charts. We further developed growth charts specific for patients with rapidly or slowly progressive MPS VI disease given their different progressions of growth.

The pre-ERT heights of patients plotted on a scatterplot were heterogeneous suggesting a possibility of a nonlinear relationship. Therefore, we used the LMS procedure to smooth the height for age scatterplots as described in the methods.

Pre-ERT height and uGAG measurements from patients ≤25 years of age were chosen for calculations to construct MPS VI growth charts. Even though data from 18 to 25 years of age were used for developing the growth curves, patients >18 years of age were not displayed due to the changing ratio between slowly and rapidly progressive disease in this age cohort limiting the dataset available for more severely affected patients because of early mortality, as well as to attenuate the flaring “right edge effect” of data truncation on statistical smoothing. Similarly, MPS VI reference growth curves in this report do not extend to the <2 years age group due to limited availability of data and the limitations of the methodology used for this age group.

Published reports suggest that MPS VI infants and toddlers have normal to accelerated growth velocity and often with above-average heights during the first year of life followed by decreased growth rates during the 2nd year (Heron et al. 2004; Scarpa et al. 2009). Although our dataset had limited height for age data for patients <2 years of age the trajectory of the MPS VI reference growth curves described in this report is consistent with growth deceleration during or after the 2nd year of life particularly in the rapidly progressing patients. As expected, the estimated median height of MPS VI patients after age 3 years was lower than the 5th percentile for height of the age-adjusted peers in the normal population (CDC).

The heights of slowly and rapidly progressing patients continue to increase during the teenage years with median heights measuring 144.1 and 109.3 cm by age 18 years, respectively. Unlike the slowly progressing patients, the median height of the rapidly progressing patients increases at a much slower rate reaching a relative plateau by approximately 10 years of age. Thus, it is not only important to use syndrome-specific growth charts for these genetic disorders but also to tailor the use of growth charts according to the severity of the disease. The CDC growth charts do not capture the differences in growth velocities or the variation in growth trajectory seen in MPS VI patients with rapidly or slowly progressive disease. Furthermore, appearance or worsening of joint contractures or scoliosis limits the ability for accurate height or length measurements in this population.

Several MPS and other disorders characterized by growth failure show a correlation of height for age with phenotypic severity as assessed by genotype or surrogate biomarkers (Decker et al. 2010; Tarquinio et al. 2010; Tylki-Szymanska et al. 2010; de Ruijter et al. 2013; Hendriksz et al. 2013; Jurecka et al. 2013). In the MPS VI population, height for age was previously reported to correspond with the pre-ERT uGAG levels (Swiedler et al. 2005; Decker et al. 2010). However, uGAG levels are naturally high in unaffected individuals during infancy (Gallegos-Arreola et al. 2000; Gray et al. 2007), and pretreatment uGAG levels in infants with MPS VI do not correlate closely with disease severity. In addition, uGAG levels decrease post-ERT (Harmatz et al. 2006; Harmatz et al. 2008), again limiting the utility of uGAG in categorizing disease after ERT has been started. Nevertheless, patients 4 - 18 years of age with rapidly progressing disease have pre-ERT uGAG levels in excess of 3 times the upper limit of normal (Swiedler et al. 2005). Although age-specific disease severity-defined uGAG levels have not been established, uGAG levels >200 μg/mg creatinine correlate with the rapidly progressive phenotype in patients <16 years of age (Hendriksz et al. 2013). Untreated patients with rapidly progressive disease usually do not survive beyond their late teens (Swiedler et al. 2005), and therefore, the >16 years age group represented in this analysis are more heavily represented by those with slowly progressive disease. This was supported in a publication on the CSP cohort where the untreated patients ≥16 years of age were found to have uGAG levels ≤200 μg/mg creatinine and reported to have slowly progressive disease (Hendriksz et al. 2013). Although a GAG-based biomarker may not be a reliable predictor of disease severity or in very young (first year of life) MPS patients before or after treatment with galsulfase, mutation analysis or determination of height using the MPS VI growth charts may provide an additional for defining rapidly progressing disease regardless of age or ERT status. Genotype-phenotype correlation studies of 105 arylsulfatase B (ARSB) gene mutations indicate that ARSB active-site mutations and nonsense or deletion mutations resulting in truncated proteins generally correlate with early onset of severe clinical phenotype and high pre-ERT uGAG levels (Karageorgos et al. 2007). Further, some MPS VI mutations have been correlated with severe clinical phenotype and lower height z-scores (Jurecka et al. 2013; Kantaputra et al. 2014).

The pathophysiology of short stature in MPS VI is not well elucidated. A combination of early bone maturation, growth failure, bone growth plate disorganization, joint contractures, and endocrine abnormalities has been proposed for short stature of patients with various MPS disorders (Polgreen et al. 2008; Decker et al. 2010; White 2011). Growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) deficiency or resistance has been reported in some patients with MPS IH (Hurler syndrome), MPS II, and MPS IIIA and in a rare case of MPS VI (Buyukgebiz et al. 1995; Polgreen et al. 2008; Gardner et al. 2011). However, others have not observed GH/IGF-1, thyroid hormone, or pituitary-hypothalamic insufficiency (in spite of a report of empty pituitary sella) as cause(s) of growth retardation in MPS VI (Von Muhlendahl and Bradac 1975; Borges et al. 2003; Decker et al. 2010). Growth plate abnormalities and disorganization secondary to GAG accumulation most likely contribute to growth failure in MPS disorders. Disruption of chondrocyte proliferative and hypertrophic zones in the growth plate secondary to GAG accumulation, cytokine/inflammatory response, and cellular dysfunction may lead to early bone maturation and impaired growth velocity (Abreu et al. 1995; Alliston 2010; Simonaro et al. 2010).

We did not observe increased acceleration in growth during preteen or early-teen years in the MPS VI patients with either slowly or rapidly progressive disease. Since most of the data presented was collected in a cross-sectional fashion through a variety of data sources, individual change in growth spurts during adolescence, if any, may not have been evident in the growth curves presented here. Further, no evidence of a growth spurt was apparent when growth curves for males and female patients were plotted separately (Supplement Fig. 1). Bone ages were not available to assess potential delays in growth and puberty. However, limited published data does not indicate differences between bone and chronological ages in MPS VI (Polgreen et al. 2014). Tanner staging was not collected in this study. However, a sub-analysis of patients who participated in previous clinical trials (n = 56) showed that when excluding prepubertal patients who were appropriate Tanner stage for age (n = 32), a large percentage (42%,10/24) of the remaining patients had delayed onset or delayed progression of puberty (Decker et al. 2010). The exact etiology of possible endocrine failure responsible for delayed puberty and possible growth failure in MPS VI patients remains unknown.

The impact of early initiation and long-term galsulfase ERT on growth is under investigation. In the galsulfase clinical trials program, increased growth rates by 1–2 cm/year were demonstrated in patients (mean age: 12 years) receiving up to 96 weeks of galsulfase ERT as compared to growth rates in MPS VI patients treated with placebo (Decker et al. 2010). There have been few studies on the impact of very early initiation of galsulfase ERT in MPS VI patients. Growth data from a retrospective study (n = 34) with follow-up data available from 32 children who initiated galsulfase ERT at mean age 2.9 years showed that 12 (37.5%) patients remained on the same growth percentiles, 3 (9.4%) moved to higher percentiles, and 17 (53%) fell below their baseline percentiles after ERT mean duration of 2.06 years (Horovitz et al. 2013). A Japanese sibling study reported that a patient who started ERT at age 5.6 years showed catch-up growth after 3 years of ERT (Furujo et al. 2011). Further investigations are needed to study if early diagnosis coupled with ERT initiation and long-term treatment may help avoid or mitigate the growth failure seen in MPS VI patients. The challenge is early recognition, and ultimately early diagnosis will depend on the development and initiation of newborn screening programs (Giugliani et al. 2007). MPS VI-specific growth charts will be an important tool to monitor growth outcomes in these ERT-treated patients.

In conclusion, we have developed reference growth charts for the rapidly and slowly progressive MPS VI patients. We encourage the use of these charts in clinical practice to help provide clinically meaningful information to physicians, patients, and parent/caregivers on expected outcomes of normal growth in this MPS VI population; provide an estimate of disease severity based on height; and assess the impact of therapeutic interventions. These charts are provided as Supplement Figs. 4–6 with this report.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was performed based on the suggestion of the MPS VI CSP publication advisory board (Drs Jim McGill, Rossella Parini, Ans van der Ploeg, Paul Harmatz, Chris Hendriksz, Christina Lampe, Vassili Valayannopoulos, and Elisa Leão-Teles). The clinical trials data was provided by the MPS VI Study Group coinvestigators (see below). This study was supported by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. and, in part, with funds provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources (NIH/NCRR) CTSA grant UL1RR024131 (Dr Harmatz). The Authors thank Prof Tim Cole, Center for Pediatric Epidemiology and Biostatistics, UCL Institute of Child Health, London, UK, for his expert advice; Ajay K. Malik, PhD, (BioMarin) for medical writing and graphics support; and Robert Matousek (BioMarin) for statistical analysis.

The MPS VI Study Group coinvestigators were Agata Fiumara, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; Ana Cecília Azevedo, MD, Serviço de Genética Médica/HCPA and Department of Genetics/UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Ana Maria Martins, MD, UNIFESP, Instituto de Oncologia Pediátrica, GRAACC/UNIFESP, Departamento de Pediatria, São Paulo, Brazil; Anne O’Meara, MD, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Dublin, Ireland; Barbara Plecko, Univ. Klinik fur Kinder und Jugendheilkunde, Graz, Austria; Prof. Billette de Villemeur, Hôpital Trousseau, Paris, France; Bonito Victor, MD, Unidade de Doenças Metabólicas, Departamento Pediatria, Hospital de Sao João, Porto, Portugal; Chester B. Whitley, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, USA; Claudia Lee, MPH, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; David Ketteridge, Department of Genetic Medicine, Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia; David Sillence, MD, Children’s Hospital, Westmead, Australia; D.N. Bennett-Jones, MD, Consultant General & Renal Physician, Whitehaven, UK; Eduardo Coopman, MD, Hospital del Cobre De. Salvador, Calama, Chile; Elio Gizzi, MD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; Elisa Leão-Teles ,MD, Unidade de Doenças Metabólicas, Departamento Pediatria, Hospital de Sao João, Porto, Portugal; Emerson Santana Santos, MD, Fundação Universidade de Ciências da Saúde de Alagoas Governador, Departamento de Pediatria, Maceió, Brazil; Eugênia Ribeiro Valadares, MD, PhD, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais-UFMG, Avenida Professor Alfredo Balena, Belo Horizonte-Minas Gerais, Brazil; Prof Giovanni Sorge, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; Gregory Pastores, MD, PhD, NYU Medical Center, Rusk Institute, New York, New York; Ida Vanessa D. Schwartz, MD, Serviço de Genética Médica/HCPA and Department of Genetics/UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Isabel Cristina Neves de Souza, MD, Universidade Federal do Pará, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto, Belém, Brazil; Javier Arroyo, MD, Hospital San Pedro de Alcantara, Hospital de día de Pediatría, Caceres, Spain; J. Edmond Wraith, MD, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK; John J. Hopwood, Department of Genetic Medicine, Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia; John Waterson, MD, PhD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; Julie Simon, RN, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; Laila Arash, Children’s Hospital, University of Mainz, Germany; Laura Keppen, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of South Dakota School of Medicine, Sioux Falls, SD; Lewis Waber, MD, PhD, Pediatric Genetics and Metabolism, University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, Dallas, TX; Lionel Lubitz, MD, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; Lorenzo Pavone, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; Luiz Carlos Santana da Silva, PhD, Universidade Federal do Pará, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto, Belém, Brazil; Maurizio Scarpa, Department of Pediatrics, University of Padova, Padova, Italy; M. Clara Sá Miranda, MD, Unidade de Biologia do Lisossoma e Peroxisoma, Instituto de Biologia Molecular e Celular, Porto, Portugal; Michael Beck, MD,Children’s Hospital, University of Mainz, Germany; Michel Kretz, MD, Hôpital Civil de Colmar, Le Parc Centre de la Mère et de l’Enfant, Colmar, France; Nathalie Guffon, MD, Hôpital Edouard Herriot Pavillon S, Maladies Metaboliques, Lyon, France; Paige Kaplan, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Paul Harmatz, MD Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; Philippe Bernard, MD, Centre Hospitalier d’Arras, Arras, France; Raquel Boy, MD, Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Ray Pais, MD, Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, East Tennessee Children’s Hospital, Knoxville, TN; Rita Barone, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; Robert Steiner, Departments of Pediatrics and Molecular and Medical Genetics, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA; Roberto Giugliani, MD, PhD, Serviço de Genética Médica/HCPA and Department of Genetics/UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Prof Rudolf Korinthenberg, Universitätsklinikum Freiburg, Zentrum für Kinderheilkunde und Jugendmedizin, Klinik II Neuropädiatrie und Muskelerkrankungen, Freiburg, Germany; Shuan-Pei Lin, MD, MacKay Memorial Hospital, Department of Genetics, Taipei, Taiwan; Silvio Pozzi, MD, Ospedale Vito Fazzi, UO Pediatria, Lecce, Italy; Simon Jones, MD, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK; Stephanie Oates, RN Department of Genetic Medicine, Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia; Susan Conrad, MD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, California; Uwe Preiss, MD, Universitaetsklinik und Poliklinik fuer Kinder, Halle, Germany; William Frischman, MD, The Townsville Hospital, Townsville, Australia; Yasmina Amraoui, MD, Children’s Hosp, University of Mainz, Germany.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CSP

Clinical surveillance program

- ERT

Enzyme replacement therapy

- GAG

Glycosaminoglycans

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- LMS

Lambda Mu Sigma

- MPS VI

Mucopolysaccharidosis VI

- uGAG

Urinary glycosaminoglycans

Synopsis

Growth charts for rapidly and slowly progressing MPS VI patients.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Christian J. Hendriksz, Rossella Parini, and Paul Harmatz have worked as consultants and study investigators for BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., received research grants, participated in BioMarin advisory board meetings, and received speaker honoraria and travel support from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. Adrian Quartel, Sue Graham, and Ping Lin are employees and stockholders of BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

Patient Consent Statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Each participant or his/her legally authorized representative provided written informed consent before entering the study in compliance with the applicable local regulations.

Contributions of Individual Authors

Adrian Quartel contributed to the conception and research design, performed data analysis, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Christian J. Hendriksz contributed to the conception and research design, acquisition of data, and revising manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Rossella Parini contributed to the conception and research design, acquisition of data, and revising manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Sue Graham contributed to the conception and research design and revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Ping Lin contributed to the research design, developed statistical methodologies, performed statistical analyses and interpretations, and revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Paul Harmatz contributed to the conception and research design and acquisition of data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Guarantor: Adrian Quartel

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Paul Harmatz, Email: pharmatz@mail.cho.org.

Collaborators: Johannes Zschocke, Matthias Baumgartner, K Michael Gibson, Marc Patterson, and Shamima Rahman

References

- Abreu S, Hayden J, Berthold P, et al. Growth plate pathology in feline mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;57(3):185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00310256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliston T. Chondroitin sulfate and growth factor signaling in the skeleton: possible links to MPS VI. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(2):129–138. doi: 10.3233/PRM-2010-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges MF, Tavares FS, Silva PCL, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome): endocrine evaluation of three cases. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2003;47(1):87–94. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302003000100014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buyukgebiz B, Eroglu Y, Kovanlikaya I, Sen A, Buyukgebiz A. Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome associated with growth hormone deficiency. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1995;8(4):305–307. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.1995.8.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ. Using the LMS method to measure skewness in the NCHS and Dutch National height standards. Ann Hum Biol. 1989;16(5):407–419. doi: 10.1080/03014468900000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1992;11(10):1305–1319. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruijter J, Broere L, Mulder MF, et al. Growth in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type III (Sanfilippo disease) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker C, Yu Z-F, Giugliani R, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI: Growth and pubertal development in patients treated with recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(2):89–100. doi: 10.3233/PRM-2010-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furujo M, Kubo T, Kosuga M, Okuyama T. Enzyme replacement therapy attenuates disease progression in two Japanese siblings with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104(4):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos-Arreola MP, Machorro-Lazo MV, Flores-Martinez SE, et al. Urinary glycosaminoglycan excretion in healthy subjects and in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses. Arch Med Res. 2000;31(5):505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(00)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CJ, Robinson N, Meadows T, et al. Growth, final height and endocrine sequelae in a UK population of patients with Hurler syndrome (MPS1H) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(2):489–497. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani R, Harmatz P, Wraith JE. Management guidelines for mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):405–418. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani R, Lampe C, Guffon N, et al. Natural history and galsulfase treatment in mucopolysaccharidosis VI (MPS VI, Maroteaux–Lamy Syndrome)—10 year follow-up of patients who previously participated in an MPS VI survey study. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray G, Claridge P, Jenkinson L, Green A. Quantitation of urinary glycosaminoglycans using dimethylene blue as a screening technique for the diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidoses: an evaluation. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44(Pt 4):360–363. doi: 10.1258/000456307780945688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JG, Allanson JE, Gripp KW, Slavotinek AM. Special section. Syndrome-specific growth charts. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(11):2645–2646. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmatz P, Whitley C, Waber L, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome) J Pediatr. 2004;144(5):574–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmatz P, Ketteridge D, Giugliani R et al (2005) Direct comparison of measures of endurance, mobility, and joint function during enzyme-replacement therapy of mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome): results after 48 weeks in a phase 2 open-label clinical study of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase. Pediatrics 115(6) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harmatz P, Giugliani R, Schwartz I, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase (recombinant human arylsulfatase B or rhASB) and follow-on, open-label extension study. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmatz P, Giugliani R, Schwartz IV, et al. Long-term follow-up of endurance and safety outcomes during enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI: Final results of three clinical studies of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94(4):469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmatz PR, Garcia P, Guffon N, et al. Galsulfase (Naglazyme(R)) therapy in infants with mucopolysaccharidosis VI. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9654-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksz C, Giugliani R, Harmatz P, et al. Design, baseline characteristics, and early findings of the MPS VI (mucopolysaccharidosis VI) Clinical Surveillance Program (CSP) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):373–384. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron D, Baumann C, Benichou JJ, Harpey JP, Le Merrer M. Early diagnosis of Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome in two patients with accelerated growth and advanced bone maturation. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163(6):323–326. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz DD, Magalhaes TS, Acosta A, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy with galsulfase in 34 children younger than five years of age with MPS VI. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton WA, Hall JG, Scott CI, Pyeritz RE, Rimoin DL. Growth curves for height for diastrophic dysplasia, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, and pseudoachondroplasia. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136(4):316–319. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1982.03970400034010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurecka A, Zakharova E, Cimbalistiene L, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Central and Eastern Europe. Pediatr Int. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ped.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantaputra PN, Kayserili H, Guven Y, et al. Clinical manifestations of 17 patients affected with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI and eight novel ARSB mutations. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;164(6):1443–1453. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgos L, Brooks DA, Pollard A, et al. Mutational analysis of 105 mucopolysaccharidosis type VI patients. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(9):897–903. doi: 10.1002/humu.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski R, Ogden C, Guo S, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman R, Martin KW, Castro S, Basto MA, Adams A, Teles EL. Radiologic and neuroradiologic findings in the mucopolysaccharidoses. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(2):109–118. doi: 10.3233/PRM-2010-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld EF, Muenzer J (2013) The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Valle D, Beaudet AL, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Antonarakis SE, Ballabio A, Gibson K, Mitchell G (eds) OMMBID – the online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseases. McGraw-Hill, New York. http://ommbid.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=474&Sectionid=45374136. Accessed 23 Jan 2014

- Polgreen LE, Tolar J, Plog M, et al. Growth and endocrine function in patients with Hurler syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(12):1005–1011. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgreen LE, Thomas W, Fung E, et al. Low bone mineral content and challenges in interpretation of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in children with mucopolysaccharidosis types I, II, and VI. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(1):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranke MB. Disease-specific growth charts–do we need them? Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1989;356:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1989.tb11236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa M, Barone R, Fiumara A, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis VI: the Italian experience. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(10):1203–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0910-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonaro CM, Ge Y, Eliyahu E, He X, Jepsen KJ, Schuchman EH. Involvement of the Toll-like receptor 4 pathway and use of TNF-alpha antagonists for treatment of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(1):222–227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912937107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiedler S, Beck M, Bajbouj M, et al. Threshold effect of urinary glycosaminoglycans and the walk test as indicators of disease progression in a survey of subjects with Mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome) Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134A(2):144–150. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarquinio DC, Motil KJ, Hou W, et al. Growth failure and outcome in Rett syndrome: specific growth references. Neurology. 2010;79(16):1653–1661. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e9a70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Montaño A, Oikawa H et al (2012) Impairment of body growth in mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Preedy V (ed) Handbook of growth and growth monitoring in health and disease. Springer, New York, pp 2091–2117

- Tylki-Szymanska A, Rozdzynska A, Jurecka A, Marucha J, Czartoryska B. Anthropometric data of 14 patients with mucopolysaccharidosis I: retrospective analysis and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-L-iduronidase (laronidase) Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Muhlendahl KE, Bradac GB. Empty Sella syndrome in a boy with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (Maroteaux–Lamy) Helv Paediatr Acta. 1975;30(2):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K (2011) Orthopaedic aspects of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50(Suppl 5):26–33 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Whitley CB, Ridnour MD, Draper KA, Dutton CM, Neglia JP. Diagnostic test for mucopolysaccharidosis. I. Direct method for quantifying excessive urinary glycosaminoglycan excretion. Clin Chem. 1989;35(3):374–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.