Abstract

Objectives

To determine prognostic factors and optimal timing of postoperative radiation therapy (RT) in adult low-grade gliomas.

Methods

Records from 554 adults diagnosed with nonpilocytic low-grade gliomas at Mayo Clinic between 1992 and 2011 were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

Median follow-up was 5.2 years. Histology revealed astrocytoma in 22%, oligoastrocytoma in 34%, and oligodendroglioma in 45%. Initial surgery achieved gross total resection in 31%, radical subtotal resection in 10%, subtotal resection (STR) in 21%, and biopsy only in 39%. Median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were 11.4 and 4.1 years, respectively. On multivariate analysis, factors associated with lower OS included astrocytomas and use of postoperative RT. Adverse prognostic factors for PFS on multivariate analysis included tumor size, astrocytomas, STR/biopsy only and not receiving RT. Patients undergoing gross total resection/radical subtotal resection had the best OS and PFS. Comparing survival with the log-rank test demonstrated no association between RT and PFS (P = 0.24), but RT was associated with lower OS (P < 0.0001). In patients undergoing STR/biopsy only, RT was associated with improved PFS (P < 0.0001) but lower OS (P = 0.03). Postoperative RT was associated with adverse prognostic factors including age > 40 years, deep tumors, size ≥ 5 cm, astrocytomas and STR/biopsy only. Patients delaying RT until recurrence experienced 10-year OS (71%) similar to patients never needing RT (74%; P = 0.34).

Conclusions

This study supports the association between aggressive surgical resection and better OS and PFS, and between postoperative RT and improved PFS in patients receiving STR/biopsy only. In addition, our findings suggest that delaying RT until progression is safe in patients who are eligible.

Keywords: low-grade glioma, clinical outcomes, radiotherapy, prognosis

Low-grade gliomas (LGGs) are primary brain tumors classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I or II.1 LGGs are most often diagnosed in children and young adults, but can occur at any age. Outcomes are highly variable based on prognostic factors reported primarily by retrospective reviews.2-4 Although a small number of prospective trials have been conducted,5-8 the optimal use and timing of radiation therapy (RT) remains controversial.

Prospective data from European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22845 reported improved progression-free survival (PFS) but not overall survival (OS) with postoperative RT.5,7 We previously conducted a retrospective study of adult LGG patients seen at Mayo Clinic between 1960 and 1992 with long-term follow-up (median 13.2 y).9 Our study confirmed the generally accepted PFS and OS benefit of extensive surgical resection. In contrast to EORTC 22845, postoperative RT was associated with improved OS and PFS in the large number of patients receiving less aggressive resections. In the present study, we extend our previous findings with an analysis of adults diagnosed with LGG at Mayo Clinic between 1992 and 2011. The goal of this study is to evaluate prognostic factors and treatment outcomes in adult LGG patients, with attention to the controversial role of RT in treating these tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Records from 554 adults diagnosed at Mayo Clinic with LGG between 1992 and 2011 were reviewed. Patients were at least 18 years of age with a WHO grade II glioma confirmed by review of pathology specimens by a Mayo Clinic neuro-pathologist. Neurofibromatosis type 1 patients were excluded from this study. Data including symptoms, extent of surgery, postoperative treatment, histologic classification, and other prognostic factors were recorded.

Postoperative imaging and operative reports, if postoperative imaging was not available, were used to determine the extent of surgical resection. Postoperative imaging was available for 387 patients (70%), which was concordant with neurosurgeon’s impression in 378 cases (98%). All 9 patients with discordance between operative reports and postoperative imaging were apparent gross total resections (GTRs) that postoperative imaging revealed to be radical subtotal resections (rSTRs). GTR was defined as no evidence of remaining tumor after excision. If GTR was unsuccessful but >80% of the tumor was removed, it was classified as rSTR. If debulking was attempted but < 80% of the tumor was removed, it was classified as subtotal resection (STR). If tumor tissue was solely obtained for diagnostic purposes and no effort was made to reduce size, it was classified as biopsy only.

Tumors were graded by WHO standards.1 Grade I tumors were excluded from this study. Grade II tumors included: astrocytomas (diffuse and gemistocytic), oligodendrogliomas, and mixed oligoastrocytomas. Progression was identified by clinical assessment, imaging, pathology reports, or other additional treatments. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. Status of 1p/19q was assessed using fluorescent in situ hybridization routinely performed in oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas diagnosed at Mayo Clinic since 2003.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors was performed to determine associations with OS and PFS. Factors chosen based on importance in previous studies2,3,6-9 included: age, symptom duration and character, tumor size, location, histology, surgery, RT, and grade.

PFS and OS curves were created using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.10 The Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Deaths occurring without documented recurrence were considered censored observations for recurrence at the time of death. This assumes all patients with unknown disease status at death or last follow-up died of disease. All tests performed were 2-tailed. Relationships between prognostic factors and extent of surgery or postoperative RT were analyzed with the χ2 test and Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

Patient, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients (539/554; 97%) had supratentorial tumors. For chemotherapy, 44 patients received a combination of procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine, and 30 received temozolomide. The median total dose of radiation delivered was 54 Gy (range, 45 to 72 Gy), delivered in (median) 30 fractions over (median) 40 days. The most common total doses were 54 Gy in 88 patients, 50 to 50.4 Gy in 42, and 59.4 Gy in 26.

TABLE 1.

Overall Patient and Treatment Characteristics (n = 554)

| Characteristic | Overall*

|

|---|---|

| 554 | |

| Age of primary histologic diagnosis (y) | |

| Mean (range) | 39.5 (18.6-76.0) |

| Age of symptom onset (y) | |

| Mean (range) | 38.3 (7.0-75.4) |

| Time from symptom onset to diagnosis (d) | |

| Mean (median) | 428 (80) |

| Follow-up time (y) | |

| Median | 5.2 |

| Time-to-recurrence (y) | |

| Median | 2.8 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 230 (42) |

| Male | 324 (58) |

| Extent of resection | |

| Gross total | 171 (31) |

| Radical subtotal | 54 (10) |

| Subtotal | 114 (21) |

| Biopsy only | 215 (39) |

| Histology | |

| Astrocytoma | 120 (22) |

| Mixed oligoastrocytoma | 187 (34) |

| Oligodendroglioma | 247 (45) |

| Location† | |

| Cortical | 532 (96) |

| Frontal | 366 (66) |

| Temporal | 163 (29) |

| Parietal | 131 (24) |

| Occipital | 30 (5) |

| Deep | 171 (31) |

| Basal ganglia/thalamus | 41 (7) |

| Corpus callosum | 48 (9) |

| Hypothalamus/third ventricle/hippocampus | 7 (1) |

| Cerebellum/fourth ventricle | 4 (1) |

| Brainstem | 11 (2) |

| Size (cm) | |

| ≥ 5 | 116 (21) |

| < 5 | 155 (28) |

| Unavailable | 283 (51) |

| Symptoms | |

| Seizures | 378 (68) |

| Headaches | 123 (22) |

| Speech | 33 (6) |

| Sensory/motor | 155 (28) |

| Postoperative | |

| RT alone | 235 (42) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 13 (2) |

| Chemotherapy/RT | 87 (16) |

| Observation | 219 (40) |

Values are number (percentage) unless otherwise noted.

Numbers exceed total number as tumors may involve more than 1 location.

RT indicates radiotherapy.

Recurrence and Progression Outcomes

Median follow-up was 5.2 years. Recurrence occurred in 330 patients. The 5-, 10-, and 15-year PFS rates were 42%, 19%, and 13%, respectively (Fig. 1A). Median PFS was 4.1 years. Adverse prognostic factors on univariate analysis for PFS included deep location, tumor size ≥ 5 cm, astrocytoma histology, STR/biopsy only, and sensory/motor symptoms (Table 2). Neither postoperative RT nor chemotherapy were associated with PFS on univariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, adverse prognostic factors for PFS included tumor size ≥ 5 cm, astrocytoma histology, STR/biopsy only, and not receiving postoperative RT (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) for all 554 patients studied.

TABLE 2.

Results From Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

| Univariate

|

Multivariate

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio | 95% CI | P | Risk Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| Age > 40 | 1.00 | 0.80-1.22 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.78-1.21 | 0.82 |

| Deep location | 1.29 | 1.03-1.61 | 0.03 | 1.16 | 0.91.1.47 | 0.24 |

| Tumor size ≥ 5 cm* | 1.77 | 1.29-2.44 | 0.0005 | 1.87 | 1.33-2.63 | 0.0004 |

| Astrocytoma | 1.60 | 1.24-2.04 | 0.0003 | 1.56 | 1.20-2.02 | 0.001 |

| GTR or rSTR | 0.60 | 0.48-0.74 | < 0.0001 | 0.49 | 0.38-0.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Headaches | 1.28 | 1.00-1.62 | 0.053 | 1.21 | 0.90-1.61 | 0.20 |

| Seizures | 0.82 | 0.66-1.03 | 0.10 | 1.09 | 0.80-1.48 | 0.59 |

| Speech | 1.25 | 0.78-1.89 | 0.34 | 0.95 | 0.58-1.48 | 0.82 |

| Sensory/motor symptoms | 1.47 | 1.16-1.84 | 0.002 | 1.30 | 0.98-1.72 | 0.07 |

| Postoperative RT | 0.88 | 0.71-1.09 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.41-0.68 | < 0.0001 |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Age > 40 | 1.48 | 1.10-1.99 | 0.009 | 1.31 | 0.97-1.78 | 0.08 |

| Deep location | 1.53 | 1.11-2.09 | 0.0094 | 1.12 | 0.80-1.56 | 0.49 |

| Tumor size ≥ 5 cm* | 1.67 | 1.06-2.63 | 0.0264 | 1.47 | 0.91-2.36 | 0.12 |

| Astrocytoma | 2.26 | 1.60-3.13 | < 0.0001 | 1.83 | 1.27-2.60 | 0.001 |

| GTR or rSTR | 0.47 | 0.33-0.65 | < 0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.46-1.02 | 0.06 |

| Headaches | 1.38 | 0.98-1.92 | 0.06 | 1.35 | 0.91-1.97 | 0.14 |

| Seizures | 0.75 | 0.55-1.04 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.58-1.36 | 0.59 |

| Speech | 1.60 | 0.84-2.76 | 0.14 | 1.12 | 0.57-2.01 | 0.74 |

| Sensory/motor symptoms | 1.45 | 1.04-2.00 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.73-1.67 | 0.63 |

| Postoperative RT | 2.60 | 1.85-3.76 | < 0.0001 | 1.79 | 1.20-2.71 | 0.004 |

Risk ratio shown excludes tumors of unknown size.

CI indicates confidence interval; GTR, gross total resection; rSTR, radical subtotal resection; RT, radiotherapy.

Patients undergoing rSTR or GTR had similar PFS (P = 0.26) and were grouped together for the remainder of this study. Patients undergoing STR had lower PFS than biopsy only (10-year PFS 8.2% with STR vs. 17% with biopsy; P = 0.02). However, because of grouping of STR and biopsy only patients in past studies9 along with the overall poor PFS in these patients, we kept the same convention and grouped them for our PFS analysis.

Extent of resection was strongly associated with PFS. Ten-year PFS for GTR/rSTR versus STR/biopsy only was 27% and 14%, respectively (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A). Factors associated with surgery achieving less than rSTR analyzed by χ2 analysis included patients older than 40 years (P = 0.0001), sensory/motor symptoms (P = 0.02), astrocytoma histology (P < 0.0001), and deep location (P < 0.0001).

FIGURE 2.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) based on extent of resection. Also seen is progression-free survival (C) and overall survival (D) based on the use of postoperative RT. GTR indicates gross total resection; rSTR, radical subtotal resection; RT, radiation therapy; STR, subtotal resection.

Postoperative RT was not associated with PFS overall (P = 0.24; Fig. 2C). However, it was associated with improved 5-year PFS (41%) versus no postoperative RT (18%) in patients receiving STR/biopsy only (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3C). Factors associated with postoperative RT are summarized in Table 3. No significant association was found between postoperative chemotherapy and PFS (P = 0.06).

FIGURE 3.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) by postoperative RT in patients undergoing GTR/rSTR. Also seen is progression-free survival (C) and overall survival (D) by postoperative RT in patients undergoing STR/biopsy only. GTR indicates gross total resection; rSTR, radical subtotal resection; RT, radiation therapy; STR, subtotal resection.

TABLE 3.

Patient Characteristics Associated With Postoperative RT on Univariate Analysis

| Factor | RT (%) | No RT (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 40 y | 48.8 | 30.2 | |

| P | < 0.0001 | ||

| Deep location | 38.2 | 20.7 | |

| P | < 0.0001 | ||

| Tumor size ≥ 5 cm* | 51.8 | 32.8 | |

| P | 0.0021 | ||

| Astrocytoma | 27.3 | 13.8 | |

| P | 0.0002 | ||

| GTR or rSTR | 20.5 | 68.5 | |

| P | < 0.0001 | ||

| Headaches | 21.4 | 23.4 | |

| P | 0.61 | ||

| Seizures | 70.2 | 65.8 | |

| P | 0.31 | ||

| Speech | 7.1 | 4.3 | |

| P | 0.20 | ||

| Sensory/motor symptoms | 29.8 | 25.5 | |

| P | 0.29 |

Excluding tumors with unknown size.

GTR indicates gross total resection; rSTR, radical subtotal resection; RT, radiotherapy.

Survival Outcomes

The median OS for the cohort was 11.4 years (range, 1 mo to 18.3 y), representing 178 deaths. The 5-, 10-, and 15-year OS rates were 81%, 56%, and 34%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Overall, 140 patients died with residual or progressive tumor and 38 died with unknown disease status. No patients documented died with no evidence of disease. At last documented contact, 148 patients were alive without disease, 216 were alive with disease, and 12 were alive with unknown disease status.

When extent of surgical resection was analyzed, we found no difference in OS between GTR and rSTR (P = 0.13) and found no difference in OS between STR and biopsy only (P = 0.48). Hence, we grouped GTR and rSTR and grouped STR and biopsy for OS analysis. Ten-year OS for patients undergoing GTR/rSTR was 66% compared with 48% for STR/biopsy only (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2B).

Adverse prognostic factors for OS identified on univariate analysis included age 40 years or older, deep tumor, size ≥ 5 cm, astrocytoma histology, STR/biopsy only, sensory/motor symptoms, and postoperative RT (Table 2). Postoperative chemotherapy was not associated with OS (P = 0.49). On multivariate analysis, factors associated with lower OS included astrocytoma histology and postoperative RT (Table 2). Extent of resection was not associated with OS on multivariate analysis. To understand this lack of significance, we conducted an exploratory multivariate analysis without RT as a variable. With RT removed, we found similar results to univariate analysis with age 40 or older, astrocytoma histology and STR/biopsy only being associated with lower OS (all P < 0.05) on multivariate analysis. Most notably, those receiving STR/biopsy only had a significantly increased risk of death (relative risk, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.7; P = 0.0005).

Overall, those receiving postoperative RT had lower 10-year OS (45%) than those not receiving postoperative RT (73%; P < 0.0001; Fig. 2D). Patients who underwent STR/biopsy only that received postoperative RT also had lower 10-year OS (46%) than those not receiving RT (60%; P = 0.03; Fig. 3D). This was also seen in patients undergoing GTR/rSTR (10-year OS, 45% vs. 78%; P = 0.0005; Fig. 3B). Postoperative RT was associated with reduced OS after GTR/rSTR (median, 9.4 y) and after STR/biopsy (median, 8.7 y) to similar rates (P = 0.23). Patients receiving postoperative RT had more adverse prognostic factors on univariate analysis (Table 3). In the 147 patients receiving postoperative RT who died, 107 died with residual or progressive tumor. In the remaining 32 patients, the cause of death was unknown and occurred a median of 2.3 years (range, 0.3 to 9.1 y) after last follow-up. At last follow-up of these patients, 7 had no evidence of tumor, 11 had stable residual tumor, and 14 had tumor progression. A total of 2 patients most likely died as a consequence of radiation necrosis.

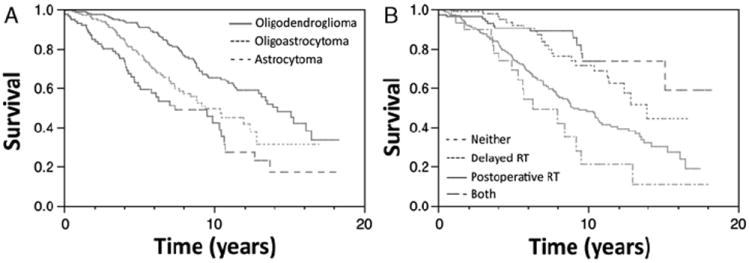

Outcomes by Histology

Astrocytomas, mixed oligoastrocytomas, and oligoden-drogliomas had 10-year OS rates of 42%, 49%, and, 65%, respectively (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4A) and 10-year PFS rates of 13%, 16%, and 23%, respectively (P < 0.0001). Astrocytoma histology was an adverse prognostic factor for OS and PFS on univariate and multivariate analysis (all P < 0.01). Testing of 1p/19q deletion status was recorded in 133 patients, with the majority having oligodendroglial tumors (128). Codeletion of 1p/19q was reported in 80% of oligodendrogliomas and 43% of oligoastrocytomas tested. Median follow-up for patients with 1p/19q testing was 4.0 years. There was no statistically significant association between 1p/19q codeletions and the use of postoperative chemotherapy (P = 0.81). Higher PFS (5 y, 49% vs. 7%; P < 0.0001) and OS (10 y, 64% vs. 30%; P = 0.0001) were seen in patients with 1p/19q codeletions. Multivariate analysis of previously assessed prognostic factors with 1p/19q status replacing astrocytoma histology as a variable revealed a significant association between 1p/19q codeletions and improved PFS and OS (both P < 0.0001). In this subgroup analysis, other factors associated with improved PFS included not having headaches or seizures, receiving postoperative RT and surprisingly, tumors in deep locations (all P < 0.05). Not receiving postoperative RT (P < 0.0001) was the only additional factor associated with OS on this subgroup multivariate analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Overall survival in patients based on histology (A). Overall survival comparing time of RT administration (B). RT indicates radiation therapy.

Radiation Dose

The median dose (54 Gy) was chosen as a cutoff to determine the effect of radiation dose on outcomes. There was a trend toward improved OS in those receiving at least 54 Gy versus those receiving less (10 years, 48% vs. 20%; P = 0.08). However, no significant difference was seen in PFS, (10 years, 22% vs. 12%; P = 0.82).

Postoperative Imaging

Postoperative imaging confirmed the neurosurgeon’s impression in 378 cases (98%). All 9 cases of discordance were GTRs by operative reports that postoperative imaging revealed to be rSTRs. There was only 1 recorded death of the 9 cases of discordance, limiting our ability to meaningfully assess differences in outcomes with statistical analysis.

OS 5 years after GTR determined by neurosurgeon’s impression was 92% versus 92% with postoperative imaging. Five-year OS after rSTR by neurosurgeon’s impression was 92% versus 90% with postoperative imaging. Rates for STR and biopsy were identical. PFS 5 years after GTR determined by neurosurgeon’s impression was 49% versus 48% with postoperative imaging. Five-year OS after rSTR by neuro-surgeon’s impression was 53% versus 55% with postoperative imaging. Again, rates for STR and biopsy were identical.

Recurrence

In the 330 patients with documented recurrence, 156 presented with symptoms. Radiographic confirmation was documented in 329. One hundred sixty-four patients underwent confirmatory biopsy, revealing higher-grade transformation in 103. Development of higher-grade transformation was not associated with extent of surgical resection (P = 0.73) or postoperative RT (P = 0.74). At recurrence, 61% of patients with higher-grade transformation received postoperative RT and 57% of patients without transformation received postoperative RT. Treatment of recurrence was documented in 277 patients. At recurrence, 203 received chemotherapy, 128 received RT, 119 underwent surgical resection, and 7 received no treatment.

Chemotherapy at recurrence was not associated with OS (P = 0.44). Those undergoing surgical excision for recurrence had higher 10-year OS (56%) compared with those not receiving surgery (41%; P = 0.047). RT at recurrence was associated with better 10-year OS (59%) versus patients not receiving RT at recurrence (39%; P = 0.0001).

Patients delaying RT until recurrence compared with those receiving RT postoperatively had higher OS (10-year OS, 71% vs. 48%; P = 0.0005). However, because of associated adverse prognostic factors, postoperative RT versus delayed RT was not associated with OS on multivariate analysis (P = 0.11). Ten-year OS with delayed RT (71%) was not significantly different from lower-risk patients never receiving RT, including those without recurrence (74%; P = 0.39; Fig. 4B). Factors associated with delaying RT until recurrence included age <40 years (P = 0.008), GTR/rSTR (P < 0.0001), non-astrocytoma histology (P = 0.0008), and non-deep tumor location (P = 0.01). On univariate analysis, prognostic factors previously assessed including age > 40 years, symptoms, histology, and deep location were not significantly different between delayed and no RT (all P > 0.05). However, GTR/rSTR (P = 0.01) and smaller tumor size (P = 0.007) were more common in those never receiving RT.

DISCUSSION

There is uncertainty regarding optimal treatment regimens in adult LGG. The goal of this study was to provide further information on prognostic factors and optimal treatment for LGG patients. With a cohort of 554 patients, this is one of the largest studies conducted retrospectively on adults with LGG.

Surgery has an important role in treating LGG. Our findings are consistent with previous studies4,6 reporting higher OS and PFS with more aggressive surgical resections (GTR/rSTR). Generally, neurosurgeons favor maximally safe resection in LGG patients.6,8,11,12 Although GTR/rSTR was not associated with OS on multivariate analysis, it was likely masked by the strong negative association between postoperative RT and OS. When RT was removed from multivariate analysis, GTR/rSTR was strongly associated with higher OS, as expected. Unfortunately, aggressive resections are not always safely achievable. We found aggressive resections were less likely to be achieved in patients with unfavorable prognostic factors including age 40 years or greater, sensory/motor symptoms, astrocytomas, and deep tumors. In patients with incomplete resections, postoperative RT is often the next treatment considered.

However, the optimal role of postoperative RT in LGG patients is less clear. Because of radiation-related toxicities13,14 and the indolent nature of LGGs, some advocate delaying RT until progression.2,3,15-18 Postoperative RT significantly improved median PFS (3.4 vs. 5.3 y, P < 0.0001) without affecting OS in EORTC 22845.5,7 In contrast, we found an association between postoperative RT and lower OS on univariate and multivariate analysis. Because this study is retrospective and patients were not randomized, RT was delivered based on risk factor stratification. In general, RT was delivered to higher-risk patients undergoing less aggressive resections. Although RT remained an adverse prognostic factor for OS on multivariate analysis, not all potential prognostic factors were considered. Thus, the association between RT and lower OS is most likely confounded by adverse prognostic factors not analyzed (mental status, imaging characteristics, molecular changes, etc.), rather than a direct adverse effect of RT. Our reported low incidence of death because of radiation necrosis and no association between postoperative RT and higher-grade transformation at recurrence make radiation-related deaths unlikely to be responsible for the lower OS in those receiving postoperative RT.

Poor survival outcomes in patients receiving RT have been reported in previous retrospective studies. Olson et al16 demonstrated a trend toward lower OS in patients receiving RT versus observation (median, 13.5 vs. 16.7 y). Leighton et al3 reported lower OS with surgery and RT compared with surgery alone (5-year OS, 62% vs. 84%; P < 0.05). Philippon et al18 reported 5-year OS rates of 55% with surgery and RT compared with 65% for surgery alone. Again, these results conflict with the gold-standard, prospective studies, finding no effect of postoperative RT on OS3,5,7,19 or our previous study reporting better OS with postoperative RT after less aggressive surgical resections.9

In addition, in the lower-risk patients not receiving RT postoperatively, we found no significant difference in OS between those never receiving RT and those receiving RT at the time of tumor progression. This is particularly interesting, because patients not experiencing recurrence were included in the group never receiving RT. Our study supports the safety of delaying RT in these patients as RT at recurrence may improve OS, potentially restoring survival to rates of patients not experiencing recurrence and never receiving RT. Thus, RT at recurrence seems to be a powerful tool in a subset of patients.

The recommendation for observation, even in low-risk LGG, however, is made with little knowledge of the impact of radiologic tumor progression on the quality of life (QOL), seizure control, cognitive function, and functional status of these patients. In addition, knowledge about the predictive role molecular markers play in predicting progression is scarce. To better assess the clinical impact and meaning of tumor progression and whether observation is a reasonable strategy for low-risk LGG, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) has recently opened a phase II trial, RTOG 0925, which will evaluate neurocognitive function, QOL, and seizure control over time and after tumor progression in newly diagnosed LGG patients undergoing observation alone after diagnosis. These outcomes will be correlated prospectively with molecular prognostic factors to help in further decision making.

One hundred (18%) patients received chemotherapy postoperatively. Chemotherapy was used to treat recurrence in 203 patients (62% of those with recurrence). Chemotherapy had no significant association with PFS when given postoperatively, nor was it associated with OS when given postoperatively or at recurrence. This is consistent with randomized, prospective studies.20,21 Temozolomide, an oral alkylating agent with proven benefits in high-grade glioma,22 has demonstrated some promise in delaying RT in newly diagnosed LGG.23,24 However, the optimal duration of treatment and expected tumor response is unclear.25,26 It is expected that EORTC, RTOG, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trials will better define the role of temozolomide in LGG.

Compared with our previous study of patients diagnosed before 1992,9 we found higher OS (10-year rate, 56% vs. 36%) and lower PFS in the present study (10-year rate, 19% vs. 27%). Both studies highlight the importance of GTR/rSTR and found better PFS with postoperative RT in patients undergoing STR/biopsy only. However, postoperative RT was previously not associated with OS overall and was associated with improved OS in STR/biopsy only patients, in contrast to our present findings. There are a variety of differences between the studies potentially causing these discrepancies. More patients in the present study underwent GTR/rSTR (41% vs. 24%) and more received chemotherapy (18% vs. 7%). Fewer patients in this study had pure astrocytomas (22% vs. 58%) and fewer received postoperative RT (58% vs. 74%). As expected, median follow-up in the present study was shorter (5.2 vs. 13.6 y), which could account for some differences in results.

In addition to its retrospective design, our study has several limitations. Although our chosen end date made the results more applicable to modern-day LGGs, it limited our follow-up. Still, our median follow-up is appropriate given the study dates and is unlikely to significantly change our results. Postoperative imaging was not available in 30% of our patient cohort and operative reports were used in those cases to evaluate extent of resection. Although operative reports are commonly used to determine the extent of resection in the literature, they are generated from the neurosurgeon’s subjective intraoperative impression, a potentially unreliable measurement. In our review of the subset of patients in which postoperative imaging was available, neurosurgeon impression had excellent correlation with postoperative imaging. Evaluation of only the subset of patients in whom postoperative imaging was available did not reveal any differences in survival outcomes by extent of resection. Other prognostic information unable to be recorded may have precluded statistically significant findings in size (51% unknown), radiographic enhancement (25%), 1p/19q (74%), p53 (not performed), and IDH1 status (not performed). Our subgroup analysis of the 133 patients with available 1p/19q status was limited in scope, but found a significant association between 1p/19q codeletions and improved OS and PFS on univariate and multivariate analysis, consistent with existing literature.27 The currently open low-risk RTOG study, RTOG 0925, will assess molecular factors and QOL in a long-term analysis of low-grade glioma patients and will be important in establishing modern prognostic factors for low-risk patients.

Furthermore, differences in patient characteristics may affect results between studies. Notably, our study cohort contained a large proportion of mixed oligoastrocytomas (34%) and oligodendrogliomas (45%), which differs from previous studies.5-9 For example, EORTC 22844 and 22845 had 26% and 38% mixed oligoastrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. This may be related to neuropathologist diagnostic preferences, but could potentially be influenced by referral bias. Survival trends were consistent with the reported histology, however, with oligodendrogliomas exhibiting higher survival than astrocytomas. Specifically, OS at 5 years was 92% for oligodendrogliomas, 77% for oligoastrocytomas, and 61% for astrocytomas. This is higher than Shaw and colleagues in 2002, reporting 5-year OS of 74% for oligo-predominant and 56% for astrocytoma-predominant tumors, though our results follow the same trend. Thus, although our histologic distribution may be different from other institutions, it seems to accurately reflect clinical prognosis. In specimens with 1p/19q data, 80% of oligodendrogliomas and 43% of oligoastrocytomas had 1p/19q codeletions, further validating our histologic classification.27,28 Because of their overall better prognosis compared with astrocytomas, RT in oligodendrogliomas may not improve29-31 or could reduce16 OS in oligo-predominant tumors.

In summary, analysis of a large cohort of patients diagnosed with nonpilocytic LGG at a single institution since 1992 reveals survival outcomes that have improved in the modern era yet still remain poor. Treatments are trending toward more aggressive surgeries and fewer patients receiving postoperative RT. Ultimately, the goal in treating LGGs should be achieving maximally safe resection. Similar to our prior report, postoperative RT seems to improve PFS in patients with less aggressive resections. Our results support our practice of immediate postoperative RT for high-risk patients, including those with deep tumors, size ≥ 5 cm, astrocytomas, receiving STR/biopsy only and patients older than 40 years. The utility of RT in these high-risk patients is further highlighted by our low reported incidence of radiation-related toxicity in this subgroup of patients. In patients where delaying RT is possible, doing so seems to be safe, though our results are restricted by the retrospective nature of this study. These findings support the historic EORTC 22845 trial and further inform the prospective, observational trial conducted through RTOG for low-risk LGG (RTOG 0925). The currently open Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study, E3F05, will be critical in addressing the long-term health outcomes of RT with or without temozolomide, with special attention to QOL and cognitive dysfunction.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janny P, Cure H, Mohr M, et al. Low grade supratentorial astrocytomas. Management and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1994;73:1937–1945. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940401)73:7<1937::aid-cncr2820730727>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leighton C, Fisher B, Bauman G, et al. Supratentorial low-grade glioma in adults: an analysis of prognostic factors and timing of radiation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1294–1301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw EG, Daumas-Duport C, Scheithauer BW, et al. Radiation therapy in the management of low-grade supratentorial astrocytomas. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:853–861. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.6.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karim AB, Afra D, Cornu P, et al. Randomized trial on the efficacy of radiotherapy for cerebral low-grade glioma in the adult: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study 22845 with the Medical Research Council study BRO4: an interim analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:316–324. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim AB, Maat B, Hatlevoll R, et al. A randomized trial on dose-response in radiation therapy of low-grade cerebral glioma: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Study 22844. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:549–556. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O, et al. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:985–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw E, Arusell R, Scheithauer B, et al. Prospective randomized trial of low- versus high-dose radiation therapy in adults with supratentorial low-grade glioma: initial report of a North Central Cancer Treatment Group/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2267–2276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schomas DA, Laack NN, Rao RD, et al. Intracranial low-grade gliomas in adults: 30-year experience with long-term follow-up at Mayo Clinic. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:437–445. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. Analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claus EB, Horlacher A, Hsu L, et al. Survival rates in patients with low-grade glioma after intraoperative magnetic resonance image guidance. Cancer. 2005;103:1227–1233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pignatti F, van den Bent M, Curran D, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in adult patients with cerebral low-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2076–2084. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultheiss TE, Kun LE, Ang KK, et al. Radiation response of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1093–1112. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swennen MH, Bromberg JE, Witkamp TD, et al. Delayed radiation toxicity after focal or whole brain radiotherapy for low-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:333–339. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000014518.16481.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Recht LD, Lew R, Smith TW. Suspected low-grade glioma: is deferring treatment safe? Ann Neurol. 1992;31:431–436. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson JD, Riedel E, DeAngelis LM. Long-term outcome of low-grade oligodendroglioma and mixed glioma. Neurology. 2000;54:1442–1448. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morantz RA. Radiation therapy in the treatment of cerebral astrocytoma. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:975–982. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198706000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philippon JH, Clemenceau SH, Fauchon FH, et al. Supratentorial low-grade astrocytomas in adults. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:554–559. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piepmeier J, Christopher S, Spencer D, et al. Variations in the natural history and survival of patients with supratentorial low-grade astrocytomas. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:872–878. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00002. discussion 878–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eyre HJ, Crowley JJ, Townsend JJ, et al. A randomized trial of radiotherapy versus radiotherapy plus CCNU for incompletely resected low-grade gliomas: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:909–914. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.6.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw EG, Berkey B, Coons SW, et al. Initial report of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9802: prospective studies in adult low-grade glioma (LGG) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:58S–58S. Abtract. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaloshi G, Benouaich-Amiel A, Diakite F, et al. Temozolomide for low-grade gliomas: predictive impact of 1p/19q loss on response and outcome. Neurology. 2007;68:1831–1836. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262034.26310.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoang-Xuan K, Capelle L, Kujas M, et al. Temozolomide as initial treatment for adults with low-grade oligodendrogliomas or oligoastrocytomas and correlation with chromosome 1p deletions. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3133–3138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricard D, Kaloshi G, Amiel-Benouaich A, et al. Dynamic history of low-grade gliomas before and after temozolomide treatment. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:484–490. doi: 10.1002/ana.21125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taal W, Dubbink HJ, Zonnenberg CB, et al. First-line temozolomide chemotherapy in progressive low-grade astrocytomas after radiotherapy: molecular characteristics in relation to response. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:235–241. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins RB, Blair H, Ballman KV, et al. A t(1;19)(q10;p10) mediates the combined deletions of 1p and 19q and predicts a better prognosis of patients with oligodendroglioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9852–9861. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cairncross G, Jenkins R. Gliomas with 1p/19q codeletion: a.k.a. oligodendroglioma. Cancer J. 2008;14:352–357. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwadate Y, Matsutani T, Hasegawa Y, et al. Favorable long-term outcome of low-grade oligodendrogliomas irrespective of 1p/19q status when treated without radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2011;102:443–449. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Souhami L, El-Hateer H, Roberge D, et al. Low-grade oligodendroglioma: an indolent but incurable disease? Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:265–271. doi: 10.3171/2008.11.JNS08983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozyigit G, Onal C, Gurkaynak M, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the management of oligodendroglioma: single institutional review of 88 patients. J Neurooncol. 2005;75:189–193. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-2057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]