Abstract

Background:

The pulsatility index (PI), measured by transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography, can reflect vascular resistance induced by cerebral small-vessel disease (SVD). We evaluated the value of TCD-derived PI for diagnosing SVD as compared with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-six consecutive cases with SVD (based on MRI) and 48 controls with normal MRI underwent TCD. Based on MRI findings, patients were categorized into five subgroups of preventricular hyperintensity (PVH), deep white matter hyperintensity (DWMH), lacunar, pontin hyperintensity (PH), and PVH+DWMH+lacunar. The sensitivity and specificity of TCD in best PI cut-off points were calculated in each group.

Results:

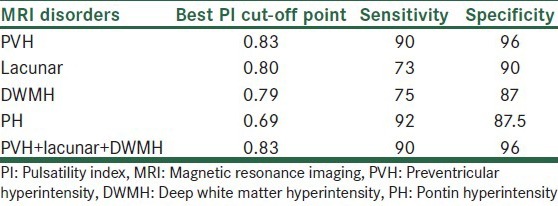

The sensitivity and specificity of TCD in comparison with MRI with best PI cut-off points were as follows: In PVH with PI = 0.83, the sensitivity and specificity was 90% and 98%, respectively. In DWMH with PI = 0.79, the sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 87.5%, respectively. In lacunar with PI = 0.80, the sensitivity and specificity was 73% and 90%, respectively. In PH with PI = 0.69, the sensitivity and specificity was 92% and 87.5%, respectively. And, in PVH+DWMH+lacunar subgroup with PI = 0.83, the sensitivity and specificity was 90% and 96%, respectively.

Conclusions:

Increased TCD derived PI can accurately indicate the SVD. Hence, TCD can be used as a non-invasive and inexpensive method for diagnosing SVD, and TCD-derived PI can be considered as a physiologic index of the disease as well.

Keywords: Cerebral small-vessel disease, diagnosis, pulsatility index, small-vessel disease, transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, vascular resistance

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral small-vessel disease (SVD) is one of the etiologies of ischemic stroke accounting for up to 20% of all strokes.[1] Because of its mortality and morbidity, early diagnosis and prompt treatment are very important.[2,3] Traditionally, diagnosis of SVD has been made only indirectly using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and by looking for evidence of brain parenchymal consequences of the disease.[4] These imaging methods, however, are capable of presenting the anatomical but not the physiological disorder. Also, while the CT scan is associated with the risks of radiation and the images have not a high quality, the MRI is quite expensive. Nowadays, techniques that directly assess brain penetrating vessels are available. Hence, it is a good idea to find a cost-benefit method that, in addition to anatomical data, can be used to simply obtain physiological data of the disease.[5]

The pulsatility index (PI) measured by transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography characterizes the shape of a spectral waveform. Firstly described by Gosling and King,[6] the PI suggested to reflect the degree of downstream vascular resistance.[5,7] Low-resistance vascular beds have high diastolic flow with rounded waveforms and lower PIs. On the other side, higher resistance beds have low diastolic flow, a peaked waveform, and higher PIs. Compared with other organs, the intracranial cerebral vasculature has relatively low downstream vascular resistance that provides a robust blood supply to the brain. One potential cause of increased downstream resistance in the cerebral circulation is narrowing of the small vessels due to lipohyalinosis and microatherosclerosis. Small-vessel blocks increases the PI that can be determined with TCD.[5]

Because of using ultrasonography, TCD is a noninvasive, inexpensive, and mobile (if needed) diagnostic method that provides physiologic data in the evaluation of stroke such as mean velocity, peak systolic velocity, and end diastolic velocity from intracranial vessels.[5,7] Some previous studies have indicated that TCD-derived PI has a sensitivity of 70-89% and specificity of 73-86%[5] and also a high negative predictive value for diagnosing SVD.[8] Other study showed that the PI is useful in determining the extent of structural changes[9] due to SVD. However, there is still lack of data in this regard. Therefore, in this study we evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of TCD with best PI cut-off points compared with MRI in diagnosing SVD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and settings

This cross-sectional study was conducted on adult patients with cerebral SVD (based on MRI) consecutively referred to the department of neurology of the Alzahra University Hospital, in Isfahan city (Iran). Those with normal pressure hydrocephalus, multiple sclerosis, non-Ischemic leukoencephalopathy and ischemic size of < 1/3 middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory were excluded from the study. The control group contains patients with normal MRI. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Assessments

Information regarding age, sex, MRI findings and TCD findings were gathered using a checklist. The MRI was done with 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (Philips company, Andover, MA, USA) in T1-weighted, T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, commonly used as sequences in evaluation of the SVD [23441036]. Based on the MRI findings, patients were categorized into five subgroups: periventricular hyperintensity (PVH), deep white matter hyperintensity (DWMH), lacunar disease, pontin hyper intensity (PH), and PVH+DWMH+lacunar.

A neurologist who was blinded to the MRI findings performed TCD for all participants using Multi-Dop X4 (DWL, Sipplingen, Germany). TCD was done bilaterally and through the temporal window on the MCA. The depth and angle of insonation giving the highest mean flow velocity was selected. MCA was selected for obtaining accurate indexes. PI was derived from the difference in the systolic and diastolic velocity divided by the mean flow velocity; PI = (PSV – EDV)/MFV.[5]

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were done using SPSS software for windows version 16.0. For determining the specificity and sensitivity of PI in different cut-off points we used ROC method. Then, the mean of PI in each group was compared with the control group. Pearson test was used for analyzing the relationship between age and PI index. A P < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

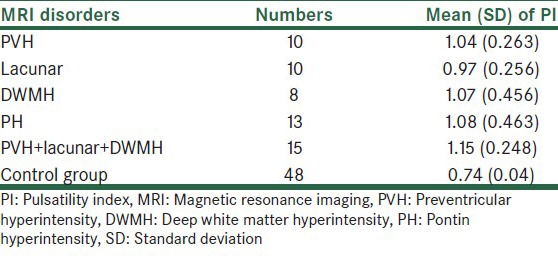

There were 56 patients in the case and 48 in the control groups. Mean age in the case and control group was 68.4 and 62.6 years, respectively (P > 0.05). The Pearson test showed that there was no significant relationship between age and PI index (P = 0.325, R = 0.134). The mean of PI index for each group are showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

PI index for each of the study groups

The mean of PI index in the control group was 0.74 in anterior cerebral artery and 0.65 in PCA. For determining the specificity and sensitivity of TCD PI we used ROC method then the mean of PI in each group was compared with the control group [Table 1]. In the PVH subgroup there was significant difference for PI index as compared with the control group (P < 0.001). In ROC method PI had sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96% as compared with MRI with the best PI cut-off point of 0.83 [Table 2]. In the lacunar subgroup there was significant difference for PI as compared with the control group (P < 0.001). In ROC method PI had sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 90% as compared with MRI with the best PI cut-off point of 0.80. In the DWMH subgroup there was significant difference for PI as compared with the control group (P < 0.001). In ROC method PI had sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 87.5% as compared with MRI with the best PI cut-off point of 0.79. In the PH subgroup there was significant difference for PI as compared with the control group (P < 0.001). In ROC method PI had sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 87.5% as compared with MRI with the best PI cut-off point of 0.69 and finally. In PVH + DWMH + lacunar subgroup there was significant difference for PI as compared with the control group (P < 0.001). In ROC method PI had sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96% as compared with MRI with the best PI cut-off point of 0.83.

Table 2.

Best PI cut points for various MRI manifestations of small-vessel disease

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that elevated PIs measured by TCD correlates well with a variety of MRI manifestations of the SVD, including periventricular hyperintensity, deep white matter hyperintensity, lacunar disease, and pontine hyperintensity. These findings support the hypothesis that the PI reflects the degree of downstream resistance in the intracranial circulation and that these measures are elevated when SVD is present.

Lacunar strokes are most commonly caused by lipohyalinosis or microatherosclerosis of small penetrating vessels.[10] Accumulating data suggest that irregular periventricular changes, deep white matter abnormalities, and pontine hyperintensity reflect a similar arteriopathic process affecting the small penetrating vessels.[11] Histopathologic studies of these processes have shown that the smooth muscle in the vessel wall is partially replaced with fibrotic material that thickens the wall and narrows the lumen.[11] It has been speculated that the thickened fibrotic wall loses its elastic properties, becoming rigid and unable to adequately dilate and constrict as needed. Of particular relevance to this study is the fact that prior studies have suggested that small arterial vessels are a significant determinant of vascular resistance.[12,13]

In a similar study,[5] Kidwell et al. retrospectively compared TCD-derived PIs and MRI manifestations of SVD in 55 consecutive patients who underwent TCD studies and brain MRI within 6 months of each other during a 2-year period. They found correlations between PIs of MCA and MRI measures in PVH, DWMH, lacunar disease, and combined PVH/DWMH/lacunes. Correlation between pontine ischemia and vertebrobasilar PIs was significant. These investigators also showed that age, elevated PI, and hypertension strongly correlated with white matter disease measures with PI as the independent predictor of white matter disease. Receiver operator curve analyses identified PI cut points that allowed discrimination of PVH with 89% sensitivity and 86% specificity and discrimination of DWMH with 70% sensitivity and 73% specificity.

Recent studies showed that PI increases in hyperlipidemia, hypertension,[14] diabetes,[15] increasing age,[16] and vascular dementia.[17] Some studies showed that another indexes in TCD not PI increase due to SVD. As an example, Bakker et al. showed strong relationship between vasomotor reactivity and periventricular white matter.[18] Molina et al. showed more decreasing in cerebrovascular reactivity in lacunar lesions.[19] In addition, Panczel and colleagues[20] reported impaired basilar artery vasoreactivity in patients with brainstem lacunar strokes compared with healthy volunteers and attributed this finding to microangiopathy within the brainstem. Puls et al.[21] demonstrated the use of TCD arteriovenous cerebral transit time measurements to evaluate the cerebral microcirculation, finding substantially prolonged transit times in patients with vascular dementia compared with controls. Our results support and extend these findings by demonstrating the correlation of more simply assessed PIs with various MRI manifestations of SVD.

Early detection of SVD may be critical in arresting this progressive disease process, allowing aggressive medical treatment including control of vascular risk factors. Thus, a TCD finding of diffusely elevated PIs may suggest previously undiagnosed small-vessel ischemic disease and prompt a search for and treatment of underlying vascular risk factors. At high values, the PI becomes highly specific (but less sensitive). For example, in our data an MCA PI of 0.83 or higher indicated combined hemispheric SVD with about 96% specificity. Future studies will be required to determine whether serial TCDs are a useful measure of either disease progression or the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions (such as antiplatelet agents).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study confirms the association of elevation in PI with MRI evidence of small-vessel disease. These findings suggest that TCD may be a useful physiologic index of the presence and severity of diffuse SVD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. We are thankful to patients who participated in this study. Also we are thankful to Dr. Ali Gholamrezaei who edited this paper.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Hennerici MG. Classification of stroke subtypes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:493–501. doi: 10.1159/000210432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mok VC, Lau AY, Wong A, Lam WW, Chan A, Leung H, et al. Long-term prognosis of Chinese patients with a lacunar infarct associated with small vessel disease: A five-year longitudinal study. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:81–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conijn MM, Kloppenborg RP, Algra A, Mali WP, Kappelle LJ, Vincken KL, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and risk of death, ischemic stroke, and cardiac complications in patients with atherosclerotic disease: The Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease-Magnetic Resonance (SMART-MR) study. Stroke. 2011;42:3105–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel B, Markus HS. Magnetic resonance imaging in cerebral small vessel disease and its use as a surrogate disease marker. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidwell CS, el-Saden S, Livshits Z, Martin NA, Glenn TC, Saver JL. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility indices as a measure of diffuse small-vessel disease. J Neuroimaging. 2001;11:229–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2001.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gosling RG, King DH. Arterial assessment by Doppler-shift ultrasound. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:447–9. doi: 10.1177/00359157740676P113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michel E, Zernikow B. Gosling's Doppler pulsatility index revisited. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1998;24:597–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok V, Ding D, Fu J, Xiong Y, Chu WW, Wang D, et al. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound for screening cerebral small vessel disease: A community study. Stroke. 2012;43:2791–3. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.665711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heliopoulos I, Artemis D, Vadikolias K, Tripsianis G, Piperidou C, Tsivgoulis G. Association of ultrasonographic parameters with subclinical white-matter hyperintensities in hypertensive patients. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/616572. 616572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher CM. Lacunar strokes and infarcts: A review. Neurology. 1982;32:871–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullicino P, Ostrow P, Miller L, Snyder W, Munschauer F. Pontine ischemic rarefaction. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:460–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1566–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper SL, Bohlen HG, Rubin MJ. Arterial and microvascular contributions to cerebral cortical autoregulation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:H17–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.1.H17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho SJ, Sohn YH, Kim GW, Kim JS. Blood flow velocity changes in the middle cerebral artery as an index of the chronicity of hypertension. J Neurol Sci. 1997;150:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)05391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KY, Sohn YH, Baik JS, Kim GW, Kim JS. Arterial pulsatility as an index of cerebral microangiopathy in diabetes. Stroke. 2000;31:1111–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titianova EB, Velcheva IV, Mateev PS. Effects of aging and hematocrit on cerebral blood flow velocity in patients with unilateral cerebral infarctions: A Doppler ultrasound evaluation. Angiology. 1993;44:100–6. doi: 10.1177/000331979304400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foerstl H, Biedert S, Hewer W. Multiinfarct and Alzheimer-type dementia investigated by transcranial Doppler sonography. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;26:590–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakker SL, de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Cerebral vasomotor reactivity and cerebral white matter lesions in the elderly. Neurology. 1999;52:578–83. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina C, Sabín JA, Montaner J, Rovira A, Abilleira S, Codina A. Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity as a risk marker for first-ever lacunar infarction: A case-control study. Stroke. 1999;30:2296–301. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panczel G, Bönöczk P, Voko Z, Spiegel D, Nagy Z. Impaired vasoreactivity of the basilar artery system in patients with brainstem lacunar infarcts. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9:218–23. doi: 10.1159/000015959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puls I, Hauck K, Demuth K, Horowski A, Schliesser M, Dörfler P, et al. Diagnostic impact of cerebral transit time in the identification of microangiopathy in dementia: A transcranial ultrasound study. Stroke. 1999;30:2291–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]