Abstract

Catatonia is a syndrome, comprised of symptoms such as motor immobility, excessive motor activity, extreme negativism, and stereotyped movements. Neuroleptic is able to induce catatonia like symptoms, that is, the neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). In NMS, patients typically show symptoms such as an altered mental state, muscle rigidity, tremor, tachycardia, hyperpyrexia, leukocytosis, and elevated serum creatine phosphorous kinase. Several researchers have reported studies on catatonia and the association between catatonia and NMS, but none were from this part of the eastern India. In our case, we observed overlapping symptoms of catatonia and NMS; we wish to present a case of this diagnostic dilemma in a patient with catatonia, where a detailed history, investigation, and symptom management added as a great contribution to the patient's rapid improvement.

Keywords: catatonia, management, neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Catatonia is a syndrome, comprised of symptoms such as motor immobility, excessive motor activity, extreme negativism, and stereotyped movements. It mainly occurs in primary mood or psychotic illness and medical and surgical conditions such as neoplasms, encephalitis, head traumas, diabetes, and metabolic disorders.[1] With the introduction of the neuroleptics, the incidence of catatonia declined.[2] However, neuroleptics are able to induce catatonia like symptoms, that is, the neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS).[3,4] In NMS, patients typically show symptoms such as an altered mental state, muscle rigidity, tremor, tachycardia, hyperpyrexia, leukocytosis, and elevated serum creatine phosphorous kinase (CPK).[5] Any antipsychotic drug including the atypical ones, can cause NMS; it is similar to catatonia and Parkinson's disease. The NMS shows strong motor symptoms with akinesia and rigidity. While the most bizarre catatonic motor symptom, like posturing, is lacking in both NMS and Parkinson’s. Moreover, unlike catatonia, the NMS neither shows affective symptoms with intense and uncontrollable emotions nor behavioral abnormities like automatic obedience, negativism, stereotypes, etc.[2]

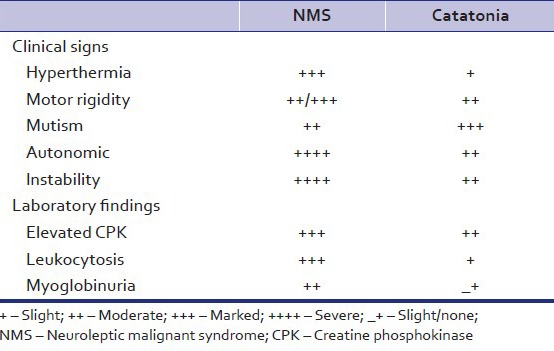

According to studies, differentiating characteristics of NMS and catatonia are as shown in table 1:[6,7]

Table 1.

Differentiating characteristics of NMS and catatonia (common variety)

Common laboratory findings of NMS include increased CPK, leukocytosis (10,000–40,000 cells/mm3 with a left shift), and myoglobinuria.[8] Other less common laboratory changes include mild elevations of hepatic enzymes (transaminase, lactic dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase). CPK is frequently elevated and often exceeds 1000 units/L. The upper limit of most reference ranges is 200 units/L. However, CPK is sensitive to disruption by many factors including intramuscular injections, muscular injuries, and exertion. It is also liable to be raised in those treated with neuroleptics who become febrile for other reasons.[9] Hence, it is not a very reliable diagnostic test. Serial estimations in documented cases indicate that rises and falls tend to correspond to fluctuations in the clinical state, so it may be considered a reasonably good marker for clinical progression of the syndrome. The role of CPK is important to detect and monitor NMS, although CPK is not specific to NMS.[10]

Recently, several researchers have reported studies on catatonia and the association between catatonia and NMS but none were reported from this part of the eastern India. Here, we report a case of catatonia with atypical presentations and symptoms resembling that of NMS and its subsequent treatment.

CASE REPORT

Ms. Aarti 23 years female admitted to female medical ward Tata Main Hospital (TMH) with acute onset mutism, complete refusal of food, stupor and generalized rigidity of the body. On detail exploration, patient had a history of abnormal behavior in the form of social withdrawal, suspiciousness, persecutory delusion, fleeting auditory hallucinations since last 1 year. She was initially treated with tablet olanzapine up to 10 mg/day, and tablet escitalopram 10 mg/day. She partially improved but voiced depressive cognitions and suicidal ideation. She was seen by another psychiatrist, where tablet escitalopram was changed to tablet venlafaxine 150 mg/day but continued with tablet olanzapine 10 mg/day. Subsequently over next 3–4 days, her clinical condition deteriorated and she was admitted to TMH.

On admission, she was afebrile, her general physical examinations including vitals were normal. She was in stuporous and mute state; there was drooling of saliva, she was resisting any limb movement and not following any command and refusing oral food and medications. There was fluctuation in her clinical picture. Her routine blood investigations were normal, but her serum CPK was found to be 3200. On 2nd day of admission, patient developed high-grade fever, on examination, patient had crepitations over the left lung, her total leukocytes count was 15,000 and she had consolidation in her left lung in X-ray. All other investigations including computed tomography scan brain were normal. She was initially treated with intravenous lorazepam up to 6 mg/day; tablet sertraline 100 mg/day and intravenous antibiotics. Her fever subsided after introduction of antibiotics but showed minimal improvement in other conditions. She was put on nasogastric feed as oral intake was very poor. Her serum CPK was monitored on a daily basis which remained persistently high (2500–3000). Provisional diagnosis of catatonia was made, and differential diagnosis of NMS was also considered. She was started on tablet aripiprazole 10 mg/day, and tablet bromocriptine 5 mg bid. Patient started showing improvement over next 4–5 days. She started speaking, taking oral food, became mobile, and her rigidity improved. All her blood investigations including serum CPK became normal. She was discharged on tablet aripiprazole 10 mg/day, tablet sertraline 100 mg/day, tablet lorazepam 2 mg/h, and tablet bromocriptine 5 mg bid. She is following up in psychiatry outpatient department TMH. She is maintaining well on tablet aripiprazole 10 mg/and tablet amisulpride 200 mg/day with a diagnosis of psychosis not otherwise specified.

DISSCUSION

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision classifies catatonia into the sub-groups of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and general medical condition.[11] Several recent studies, however, point out an association between catatonia and both neuroleptic use.[12] The researchers attempt particularly to define catatonia due to neuroleptics by first classifying the causes of catatonia as spontaneous, psychogenic, or neuroleptic.[13] In this case, on admission, patient had catatonic symptoms such as mutism, forced rigidity, negativism, and mental stupor. In addition, patient had drooling of saliva, tremor, and fever with raised CPK (3200) leading us to suspect NMS. But as literature suggests, there is a significant overlap of symptoms of NMS and catatonia. The index case was on the same dose of neuroleptic (10 mg of tablet olanzapine) since a long time. Though there are studies reporting olanzapine-induced NMS,[14] but it was considered a remote possibility in our case. Further, on detailed physical examination, the reason for fever and leukocytosis was due to pneumonia which became normal once treated with antibiotics. Thus, the absence of fever, leukocytosis, autonomic instability, cogwheel rigidity, and altered sensorium indicated more toward the definitive diagnosis of catatonia rather than NMS. But such a high CPK levels, tremor in hands and drooling of saliva were symptoms which are typically not described in catatonia. Though, the role of CPK is important to detect and monitor NMS, but CPK is not specific to NMS,[10] our case reiterates the old knowledge about this. Patient's clinical picture did not point towards the consideration of serotonin syndrome and in view of initial diagnostic confusion of catatonia due to depressive disorder versus psychosis, sertraline was continued which helped the recovery without any further deterioration. Poor initial response to lorazepam and rapid response to bromocriptine added to the diagnostic dilemma. Due to several characteristics, some researchers consider catatonia and NMS to be disorders along a single spectrum[15] and there are even such reports as that of Tsai et al.,[16] stating NMS and catatonia are in the same “neuroleptic toxicity spectrum” category, and of Mathews and Aderibigbe,[17] regarding NMS as a severe subtype of catatonia, classified as “drug-induced hyperthermic catatonia.”

Summing up, in this case, we observed overlapping symptoms of catatonia and NMS. In our case, detailed history taking, investigation, and symptom management added as a great contribution to the patient's rapid improvement.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fink M. Treating neuroleptic malignant syndrome as catatonia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:121–2. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200102000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northoff G, Eckert J, Fritze J. Glutamatergic dysfunction in catatonia? Successful treatment of three acute akinetic catatonic patients with the NMDA antagonist amantadine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:404–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fink M. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and catatonia: One entity or two? Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fricchione G, Mann S, Caroff S. Catatonia, lethal catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatry Ann. 2000;30:347–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasan S, Buckley P. Novel antipsychotics and the neuroleptic malignant syndrome: A review and critique. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1113–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caroff SN. The neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980;41:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly JJ, Crowe SF, Lloyd JH. Neuroleptic toxicity syndromes: A clinical spectrum. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991;25:499–505. doi: 10.3109/00048679109064443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones EM, Dawson A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: A case report with post-mortem brain and muscle pathology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:1006–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.8.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adnet P, Lestavel P, Krivosic-Horber R. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:129–35. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Dwyer AM, Sheppard NP. The role of creatine kinase in the diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychol Med. 1993;23:323–6. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarrouf FA, Bhanot V. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: Don’t let your guard down yet. Curr Psychiatry. 2007;2:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhossche DM, Carroll BT, Carroll TD. Is there a Common Neuronal Basis for Autism and Catatonia? Catatonia in Autism Spectrum Disorders. In: Dhossche D, Wing ML, Ohta M, Neumarker K, editors. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Academic Press, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodbury MM, Woodbury MA. Neuroleptic-induced catatonia as a stage in the progression toward neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1161–4. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patra BN, Khandelwal SK, Sood M. Olanzapine induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:98–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.106448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northoff G, Krill W, Eckert J, Russ B, Flug P. Subjective experience of akinesia in catatonia and Parkinson's disease. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 1988;3:161–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai JH, Yang P, Yen JY, Chen CC, Yang MJ. Zotepine-induced catatonia as a precursor in the progression to neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1156–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.8.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews T, Aderibigbe YA. Proposed research diagnostic criteria for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2:129–44. doi: 10.1017/S1461145799001388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]