Abstract

Pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs) are characterized by several impairments in the domains of social communication, social interaction and expression of social attachment, and other aspects of development like symbolic play. As the role of drugs in treating these impairments is extremely limited, a variety of psychological interventions have been developed to deal with them. Some of these have strong empirical support, while others are relatively new and hence controversial. Though it may prove to be a daunting task to begin with, the final reward of being able to improve the life of a child with PDD is enormous and hugely satisfying. Therefore, knowledge of these psychological interventions is important for a mental health professional, in order to be effective in the profession. Present paper presents an overview of these techniques in the management of PDD.

Keywords: Autism, pervasive developmental disorders, psychological interventions

The first awareness that the newest member of the family may have special problems with receptive or expressive language use in social communication, social interaction and expression of social attachment can come as a shock to the parents with numerous associated uncertainties. They generate numerous questions: What are pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs)? What constitute these unique and challenging disorders? Whether it is mild or severe? Is it curable? Can anything be done about them? The nature, etiology, assessments, and the available treatment are some of the issues that have to be dealt with. PDDs, under ICD-10, comprise of a conglomeration of categories that include childhood autism, atypical autism, Rett's syndrome, other childhood disintegrative disorder, overactive disorder associated with mental retardation and stereotyped movements, Asperger's syndrome, other PDDs and PDD, unspecified.[1] The conditions lead on to disabilities in virtually all the psychological and behavioral sectors with prominent disturbances in social, communicative, and cognitive spheres.

MODIFYING PROBLEM BEHAVIORS IN PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER

The first use of behavioral intervention appears to be done by Thorndike.[2] His major contribution was the description of the law of effect. Since then, over course of a century, our understanding of PDDs has radically changed. With the recognition that these conditions might have a biological basis, an intellectual context in which behavioral and educational interventions could take root developed. Subsequently, investigations on the role of learning in behaviors in PDD[3] promoted an appreciation for highly structured, carefully planned behavior-based interventions in these individuals.

While planning such interventions, it is important to define the premises clearly. Broadly, they would have four goals: A reduction in maladaptive behaviors, improving communication and social interactions, and parent training.[4] Therefore, to begin with, it becomes imperative to clearly identify target behaviors that need to be addressed, on an individual basis. While this constitutes initial assessment, it should simultaneously be flexible enough to accommodate changes as demanded by the progress, building on acquired gains.

Successful intervention starts with a proper assessment. The first step is to comprehensively review current concerns; regarding communication, social, and other behaviors; and early developmental history. Multi-source evaluation, combined with direct observation of and interaction with the child, may be needed. Next important domain for assessment is intellectual functioning. Intellectual functioning influences severity of autistic symptoms as well as subsequent abilities to acquire skills and adaptive functions;[5] thus facilitating rehabilitative planning and prognostication. This is followed by an evaluation expressive language level and adaptive behavior. Together, they allow the therapist for setting appropriate goals in treatment planning.[6] Beyond this proposed “core battery” of assessment for PDD, neuropsychological testing may be able to provide greater clarity about the individual's profile of strengths and weaknesses, an important foundation for treatment and educational planning[7] as well as for monitoring gains. Extended evaluation may also include measurement of academic abilities; psychiatric and other comorbidities and assessment of the family system and community resources;[8] latter being important for service delivery and related outcomes.

Identifying target behaviors in PDD is important first step. A “behavioral cusp,” as defined by Rosales-Ruiz and Baer,[8] is “a behavior change that has consequences for the organism beyond the change itself.” Bosch and Fuqua[9] have qualified behavioral cusps; and propose that a change in behavioral cusp would lead to “access to new reinforcers, contingencies, or environments” not previously encountered. This change would also meet “the demands of the social community of which the learner is a member;” facilitate “subsequent learning by being either a prerequisite or a component of more complex responses;” and the changes must interfere with or replace inappropriate behaviors in a way that benefits other stakeholders in caregiving. When some behavior is targeted, it must be clearly defined in objective, observable, and quantifiable terms; to plan adequately, enhance accountability and promote cross-caregiver communication and collaboration.

Once the maladaptive behavior is identified, there are various techniques to reduce these and to teach new skills, which we shall discuss presently. To begin with, we discuss applied behavioral analysis (ABA). It is based on experimentally derived principles of behavior, analyzed within the framework of a three-term contingency of operant conditioning of “antecedents,” behavior itself, and “consequences;” with reinforcements and punishments, applied judiciously to modify behavior.[10] The aim is to understand the function of problem behavior; which might be consequent upon deficits in skills; subsequently reducing it by helping the child attain same function through an adaptive behavior. To increase socially appropriate behaviors, ABA focuses on teaching small, measurable units of behavior systematically. Targeted skills are broken down into small steps using task analysis, and each step is taught using behavioral techniques such as shaping, prompting, and chaining. Apart from that, differential reinforcement techniques and punishment procedures are used to decrease maladaptive behaviors.[10,11] Unconditioned aversive stimuli like water spray directly on the face or a mild tick or pungent odors may be successful in managing stereotyped behaviors. Conditioned aversive stimulus, overcorrection and response interruption and redirection are other methods, latter being especially useful in reducing vocal stereotypy and increase appropriate vocalizations through use of social reinforcement for appropriate vocalizations.[12]

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION IN PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER

The methods of improving communication in PDD employ either verbal procedures like time delay and milieu teaching or nonverbal procedures like augmentative and alternative communication systems (AACs) likes sign language, photographs, etc. There is now a large body of empirical support for the effectiveness of former approaches in teaching speech, language, and communication skills to children with PDD,[13,14] simultaneously inculcating spontaneity and generalization. AAC interventions aim to assist individuals with severe communication disorders[15] and involve processes by which information is gathered and analyzed in a way so that users, and those who assist them, can make informed decisions. This participation model,[15] a widely used process in AAC, addresses three primary assessment goals: Gathering information about communication needs; assessing abilities with regard to the sensory, receptive language, expressive communication, symbol representation, lexical organization, and motor skills needed for communication; and investigating interaction strategies used by frequent communication partners and identify barriers that limited child's opportunities to communicate. Aided language stimulation (ALS) is an AAC and “input + output” approach which teaches individuals to understand and use visual-graphic symbols for communication.[16] In ALS, a communication partner, while communicating verbally with the user, highlights symbols on the user's communication display. Augmented input is achieved when the facilitator points to or highlights symbols while he or she is talking. Augmented output is elicited from the user through the use of a rather elaborate hierarchy of nonverbal and verbal instructional strategies.[17] The picture exchange communication system (PECS)[18] is a six-step approach for those children with PDD, who have limited or no verbal communication skills. Using PECS, a child is taught to spontaneously initiate communicative interaction using a picture card to request a desired item or to comment on something he observes. Typically, requesting skills are the first skills taught to children with PDDs. The use of sign language is often helpful, especially for children who are nonverbal or who have very limited verbal skills. It can be used alone, or can be combined with verbalizations to accompany the gestures, also commonly referred to as signed speech, simultaneous communication, or total communication. Some children with PDDs learn more easily when using signed speech, while others have trouble associating auditory with visual symbols, and are best taught using sign alone. A subgroup of children with PDDs also have difficulty with learning to imitate motor patterns (called dyspraxia), and sign language may be too difficult for these children. Often, children who learn sign language are also provided with some sort of picture communications system so that they have a mechanism for communicating with people who do not know sign language.[19] Interestingly, while as many as half of children with PDDs do not talk at all; others may have rich vocabularies but struggle with the use of language in context of socially appropriate communication. Thus, it might cause frustration for the child and contribute to tantrums, self-injurious behavior, and aggression.

IMPROVING SKILLS IN PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER

Deficits in appropriate social skills might hinder functioning in PDD, and this might complicate attempts at the habilitation of the individual. A useful instructional procedure that facilitates initiation and generalization of such skills is incidental teaching (IT). It refers to instruction that focuses on teaching children directly whenever the child shows motivation to request an item or activity in the natural environment.[20] In IT, while the teachers carefully select target behaviors to meet each child's individual needs and abilities, materials or activities are selected by the individual according to his or her interests and motivation. Another approach to enhance initiation and generalization of skills in children with PDDs is pivotal response training (PRT)[21] in which “pivotal response” refers to responses that seem to be central to many different aspects of functioning in children with PDD; such that changes in these skills influence a multitude of behaviors. In PRT, the focus is on pivotal responses such as motivation, responsivity to multiple cues, self-management, and self-initiation; instead of being taught one at a time.[21] Time delay is a prompting procedure in which delay is imposed between a stimulus and a prompt or a hierarchy of prompts. The delay can be held constant or lengthened progressively or until the child anticipates the prompt and produces the desired verbal or motor responses.[22]

To improve social interactions in PDD, DIR®/Floortime provides a comprehensive framework. It focuses on helping children to relate, think, and communicate; instead of focusing on treating a set of symptoms or problem behaviors.[23] This involves an interdisciplinary approach to develop skills in all areas, including social-emotional functioning, motor skills, body awareness, and attention. The term DIR stands for the three components of this approach: Developmental milestones that every child must master for healthy emotional and intellectual growth; individual-difference, which refers to unique sensory processing in each child, and their impact on behavior; and relationship-based, which focuses on helping the child to form relationships with primary caregivers and peers, and methods of interaction that will help to foster further development. Central to this approach is an intensive home program, called Floortime, in which parents and other helpers play with the child on his or her own developmental level, and gradually entice the child to interact and attend to play and to social interactions.

The use of social stories is a concept developed by Gray.[24] Impairment with reciprocal social interaction is one of the diagnostic hallmarks of people with PDD, and social stories may help in better understanding social situations, thus appreciating feelings and attitudes of others. They are individualized and are written in first person and present tense. They incorporate simple and clear descriptions of specific social cues and corresponding appropriate behaviors. Because many children with PDDs are visual learners, the stories may be illustrated, recorded on videotape, or may use concrete objects as a props. The stories are constructed using specific pattern of sentences; starting with a descriptive sentences, then a perspective sentences, one or two directive sentences that teach the child a specific response to the situation, and finally control sentences to help the child remember underlying concepts in that story.

Video modeling is a specialized teaching,[25] which entail presenting the child with a videotaped sample of how to behave in certain selected social situations. They can produce rapid learning of a variety of skills in children with PDD; like play, self-care activities, communication in social situations, and behavior under challenging circumstances. Video self-modeling involves showing children their own positive performances of a target[26] while video models of others[27] involves having children with PDD watch a videotape of other children perform a target behavior successfully. Children are then verbally praised for attending to the video before being asked to repeat the behavior. Techniques using ecological variations promote social interactions and its development through manipulations or arrangements of general features of the physical or social environment. Koegel et al.[21] found that children with PDD tend to engage in more social interaction when the activities and the materials that appear to them are more predictable. An interesting approach is collateral skills intervention, in which increased social interaction emerge as a function of training in other seemingly different skills. Social skills groups are a broad category of interventions in which a small group of children with PDD is brought together on a regular basis to receive specific instruction in relevant social skills. Groups vary in frequency and duration of sessions, number and type of children involved, as well as content of instruction.[28] Curriculum or teaching materials also tend to vary across skills groups.

NEWER BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS FOR PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER

Other than those described above, there exist some controversial approaches to PDD management. Interactions with animals are believed to reduce stress, increase motivation and sense of well-being, and increase communication skills. Animal assisted activities, resident animals, and human-animal support services have all been used in children with PDD with mixed results.[29] Art therapy utilizes art materials and creative process to improve physical, mental, and emotional well-being of individuals, allowing individual to fully express their feelings and emotions.[30] It is especially effective for children, who tend to have more difficulty than adults when expressing themselves using words. A number of auditory training programs have been developed to address the needs of children and adults who have central auditory processing disorders as a result of developmental disabilities. Of these, auditory integration training is the most widely used and researched methods.[31] This therapy consists of wearing earphones and listening to music that has been computer-modified by reducing the predictability of auditory patterns, and removing frequencies that cause sensitivity. Treatment is usually concluded at the end of 10 days but may be repeated after an interval of 9–12 months for some patients. Dance or movement therapy is the psychotherapeutic use of movement and dance to promote social, cognitive, emotional, and physical development. As a profession, dance therapy began with the work of Chace, and presently is widely used with people who have serious emotional disturbances, including children with PDD.[32,33]

Holding therapy or regulatory bonding therapy is based upon the assumption that many childhood behavior disorders stem from a stress-related physiological phenomenon in which the parent fails to bond with the child. During holding therapy, an adult (may not be the parent) forcefully restrains the child while talking, poking or tickling to elicit a reaction, and make an eye contact. Even if the child struggles, the adult does not release the child until he or she initiates eye contact with the parent, a sign believed to indicate that the child is ready to interact and bond with the adult.[34] Intensive Interaction refers to a method for supporting and developing nonverbal communication and socialization skills in children and adults with severe or profound disabilities. This approach builds upon the concept of augmented mothering,[35] where continued infant-mother interaction gradually enables the infant to develop the ability to communicate more intentionally so that his or her needs are met more easily. Rhythmic entrainment intervention (REI) is a music medicine program that is based on the principle of entrainment,[36] in which, following an assessment of the child's unique cognitive and behavioral characteristics, the REI provider develops two personalized CD percussion recordings, with rhythms selected to address specific areas of concern, such as communication skills, attention span, self-stimulatory behavior, aggression, or anxiety. Through the process of entrainment, the auditory rhythms chosen for the child are believed to stimulate the central nervous system and ultimately to improve brain function.

Sensory integration (SI) therapy[37] is based on the ability of the child's central nervous system to organize multiple sensations from the environment and from within the body; and to make adaptive responses necessary for learning and for behavioral regulation. Signs of sensory processing difficulties may include over- or under-sensitivity to certain sensory experiences, abnormally high or low activity level, poorly organized behavior, poor coordination and motor learning, or delays in language development or academic progress despite adequate intelligence. It is one of the most common approaches for children with PDD, and the schedule for this is sometimes referred to as designing a sensory diet for the child. Finally, touch therapy is a particular method of massage that involves specific sequences of rubbing the body using moderate pressure and smooth, stroking movements. Proponents of touch therapy suggest it may be beneficial for children with PDD, who often have problems with touch aversion, withdrawal, and inattentiveness.[38]

UTILITY AND SHORTCOMINGS OF THE METHODS

The behaviors of paramount concern in children with PDD include stereotypy, self-injurious behaviors, and aggression. These must be dealt with early and decisively, before they start interfering with and clout the learning process in profound ways. Methods which work on operant principles have been used in the management of maladaptive behaviors in PDD. However, implementing reinforcement procedures require a constant monitoring of the occurrence or nonoccurrence of problem behavior in order to instil an adequate schedule for reinforcement, thus limiting practicality. Punishment-based procedures are sparingly recommended in cases where the occurrence of stereotypy is debilitating for the individual's quality-of-life or when other types of methods desist successful implementation. Moreover, punishments should be immediate and of enough intensity to suppress the behavior.[39] Research in the area of communication favors adoption of learning-based methods with regard to its effectiveness.[40] PECS score better in research over manual signs, for the latter involves motor planning and motor imitation, tasks difficult for these children to accomplish. On this line, Brunner and Seung[41] argues that though use of sign language training has received strong empirical support through the years, research comparing sign language training to other treatment methods is quite limited with mixed findings. Other and newer options like holding therapy, animal assisted therapy, SI, and a number of others, as discussed above, still remain controversial. Interventions aimed at improving social skills of children with PDD depend on a number of factors: The initiator of social exchange (adult vs. peer), the context (individual vs. group teaching), and specific social goals being taught (initiations vs. response, play, etc.). Studies suggest an improvement in social skills of children with PDD with intervention, but the gains may not generalize to more naturalistic contexts or produce changes in teacher-reported social behavior.[42] Floortime™ intervention[43] and video modeling[44] have been shown to be effectiveness in the treatment of individuals with autism; Peer-mediated techniques have been shown to be particularly effective in engendering generalizability in PDD.[45]

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

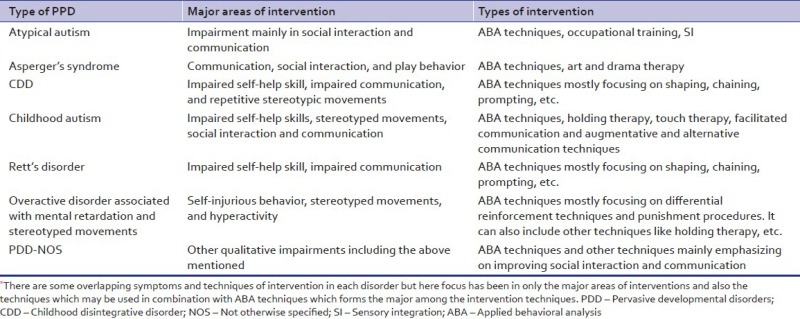

We discussed various methods [Appendix 1] which may be used to improve different skill-sets in a person with PDD. The uniqueness of treatment research in PDD is that it makes a very heterogeneous group, thus commanding an enormous range of interventions. Research over the past decade suggests that remarkable advances can be made for dramatic improvements in symptoms with concerted efforts. The progress that have made so far gives us reasons enough to feel optimistic for the future.

Appendix 1: Classification specific management in PDD

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorndike EL. New York: Macmillan; 1911. Animal intelligence: Experimental Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartak L, Rutter M. Educational treatment of autistic children. In: Rutter ML, editor. Infantile Autism: Concepts, Characteristics and Treatment. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1971. pp. 258–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health; 1999. New York State Department of Health Early Intervention Program. Clinical Practice Guideline, Autism/Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Assessmentand Intervention for Young Children. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens MC, Fein DA, Dunn M, Allen D, Waterhouse LH, Feinstein C, et al. Subgroups of children with autism by cluster analysis: A longitudinal examination. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:346–52. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szatmari P, Bartolucci G, Bremner R, Bond S, Rich S. A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1989;19:213–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02211842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser-Cram P, Warfield ME, Shonkoff JP, Krauss MW, Sayer A, Upshur CC. Children with disabilities: A longitudinal study of child development and parent well-being. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2001;66:i–viii. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosales-Ruiz J, Baer DM. Behavioral cusps: A developmental and pragmatic concept for behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal. 1997;30:533–44. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch S, Fuqua RW. Behavioral cusps: A model for selecting target behaviors. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34:123–5. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zirpoli TJ, Melloy KJ. New York: Maxwell Macmillan International; 1993. Behaviour Management Applications for Teachers and Parents; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matson JL, Tureck K, Turygin N, Beighley J, Rieske R. Trends and topics in Early Intensive behavioural interventions for toddlers with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;27:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahrens EN, Lerman DC, Kodak T, Worsdell AS, Keegan C. Further evaluation of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. J Appl Behav Anal. 2011;44:95–108. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delprato DJ. Comparisons of discrete-trial and normalized behavioral language intervention for young children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:315–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1010747303957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein H. Communication intervention for children with autism: A review of treatment efficacy. J Autism Dev Disord. 2002;32:373–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1020589821992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beukelman D, Mirenda P. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes; 1998. Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Management of Severe Communication Disorders in Children and Adults. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goossens C, Crain S, Elder P. Birmingham, AL: Southeast Augmentative Communication Conference Publications; 1995. Engineering the Preschool Environment for Interactive, Symbolic Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romski MA, Sevcik RA. Baltimore: Brookes; 1996. Breaking the Speech Barrier: Language Development through Augmented Means. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bondy A, Frost L. The picture exchange communication system. Focus Autistic Behav. 1994;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tincani M. Comparing the picture exchange communication system and sign language training for children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2004;19:152–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGee GG, Krantz PJ, Mason D, McClannahan LE. A modified incidental-teaching procedure for autistic youth: Acquisition and generalization of receptive object labels. J Appl Behav Anal. 1983;16:329–38. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1983.16-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koegel L, Koegel R, Shoshan Y, McNerney E. Pivotal response intervention II: Preliminary long-term outcomes data. J Assoc Pers Sev Handicaps. 1999;24:186–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlop-Christy MH, Carpenter M, Le L, LeBlanc LA, Kellet K. Using the picture exchange communication system (PECS) with children with autism: Assessment of PECS acquisition, speech, social-communicative behavior, and problem behavior. J Appl Behav Anal. 2002;35:213–31. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenspan SJ, Wieder S. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press; 2006. Engaging Autism: Helping Children Relate, Communicate, and Think with the DIR Floortime Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray C. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc; 2000. The New Social Story Book. Illustrated edition. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson RL. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press; 2005. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Interventions and Treatments for Children and Youth. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buggey T. VSM applications with students with autism spectrum disorder in a small private school setting. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2005;20:52–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCoy K, Hermansen E. Video modeling for individuals with autism: A review of model types and effects. Educ Treat Children. 2007;30:183–213. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barry TD, Klinger LG, Lee JM, Paslardy N, Gilmore T, Bodin SD. Examining the effectiveness of an outpatient clinic-based social skills group for high-functioning children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:685–701. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000006004.86556.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arkow P. 9th ed. Stratford, NJ: Phil Arkow/!deas; 2004. Animal-Assisted Therapy and Activities: A Study, Resource Guide, and Bibliography for the Use of Companion Animals in Selected Therapies. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards D. London: Sage Publications; 2004. Art Therapy. Creative Therapies in Practice Series. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berard G. New Canaan, CT: Keats Publishing Inc; 1993. Hearing Equals Behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chace M. Dance as an adjunctive therapy with hospitalized mental patients. Bull Menninger Clin. 1953;17:219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pratt RR. Art, dance, and music therapy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2004;15:827–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2004.03.004. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welch MG, Northrup RS, Welch-Horan TB, Ludwig RJ, Austin CL, Jacobson JS. Outcomes of prolonged parent-child embrace therapy among 102 children with behavioral disorders. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006;12:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caldwell P. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. From Isolation to Intimacy: Making Friends Without Words. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strong J. Rhythmic Entrainment Intervention (Rei): Blending Ancient Techniques with Modern Research Findings. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayres AJ. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1979. Sensory Integration and the Child. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escalona A, Field T, Singer-Strunck R, Cullen C, Hartshorn K. Brief report: Improvements in the behavior of children with autism following massage therapy. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:513–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1012273110194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson RH, Iwata BA, Conners J, Roscoe EM. Effects of reinforcement for alternative behavior during punishment of self-injury. J Appl Behav Anal. 1999;32:317–28. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coe D, Matson J, Fee V, Manikam R, Linarello C. Training nonverbal and verbal play skills to mentally retarded and autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1990;20:177–87. doi: 10.1007/BF02284717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunner DL, Seung H. Evaluation of the efficacy of communication-based treatments for autism spectrum disorders: A literature review. Commun Disord Q. 2009;31:15–41. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoder P, Stone WL. A randomized comparison of the effect of two prelinguistic communication interventions on the acquisition of spoken communication in preschoolers with ASD. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49:698–711. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/051). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wieder S, Greenspan SJ. Can children with autism master the core deficits and become empathetic, creative and reflective? A ten to fifteen year follow-up of a subgroup of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) who received a comprehensive developmental, individual-difference, relationship-based (DIR) approach. J Dev Learn Disord. 2005;9:39–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schreibman L. Intensive behavioural psychoeducational treatments for autism: Research needs and future directions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:373–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1005535120023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldstein H, Kaczmarek L, Pennington R, Shafer K. Peer-mediated intervention: Attending to commenting on, and acknowledging the behaviour of preschoolers with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;25:289–305. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]