Abstract

Double layered peritoneal folds or ligaments act as conduits for the passage of blood vessels in intraperitoneal organs and also provide a pathway for the spread of disease. It is difficult to identify these normal peritoneal folds at imaging. Computed tomography is the most common imaging modality used to detect diseases of the peritoneum. The ultrasound (US) has been also used for evaluation of diseases involving ligaments. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is being increasingly used both for diagnostic and interventional purposes in abdomen. In this article, we have described the normal EUS anatomy of the peritoneal ligaments.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, liver, peritoneal ligaments

INTRODUCTION

Double layered peritoneal folds, variously named as ligaments, omenta and mesenteries, connect the intraperitoneal organs to the abdominal wall. Some of these ligaments contain blood vessels and lymph nodes (LNs) while others are avascular.[1] The peritoneal folds not only act as conduits for the passage of blood vessels and lymphatic's from the retro peritoneum to reach intraperitoneal organs, but also provide a pathway for the spread of disease processes.[2,3] The peritoneal folds also form boundaries of various peritoneal spaces or recesses and become well delineated by fluid collection or abscess formation affecting the spaces.[4,5] It is difficult to identify these normal peritoneal folds at imaging. Computed tomography (CT) is the most common imaging modality used to detect diseases of the peritoneum fully to delineate peritoneal anatomy and the extent of disease.[1] Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is increasingly used to depict peritoneal disease. Disadvantages of MR imaging include motion artifacts caused by respiration and peristalsis and chemical shift artifacts at the bowel-mesentery interface.[6] The ultrasound (US) finding of abnormalities includes nodal involvement from metastatic tumors, contiguous spread of primary neoplasia and presence of collaterals in portal hypertension.[7] A specific advantage of US is its portability, which allows patients who are ill and who cannot be safely moved from their hospital beds to be imaged.[8] Compared with CT, other advantages of US are its lack of ionizing radiation and lower cost. Though endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is being increasingly used both for diagnostic and interventional purposes in abdomen, it has not been used to assess the peritoneal ligaments till now. In this article, we have described the normal EUS anatomy of the peritoneal ligaments.

EMBRYOLOGY OF PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS

Most peritoneal ligaments arise from the ventral or dorsal mesentery of the gut. The liver and its ligaments arise in the ventral mesentery, (ventral mesogastrium) whereas the stomach, spleen and pancreatic tail and their ligaments develop in the dorsal mesentery of the foregut (dorsal mesogasrium). The ventral part of the ventral mesentery becomes the falciform, coronary and triangular ligaments and the dorsal part of the ventral mesentery becomes the lesser omentum (hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal parts). The derivatives of the dorsal mesogastrium include gastrophrenic, gastrosplenic, lienorenal ligaments and greater omentum (gastrocolic ligament). At the level of spleen, the ventral part of the dorsal mesentery becomes the gastrosplenic ligament, and the dorsal part of the dorsal mesentery becomes the splenorenal ligament. Above the level of spleen the dorsal mesentery gives rise to gastrophrenic ligament and below the level of spleen it gives rise to gastrocolic ligament.[3]

ECHOENDOSCOPE POSITION DURING IMAGING FROM ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASOUND

Four positions are commonly used during imaging from EUS. The neutral position is where the front of the handle is facing the patient. The open position to the left is where the front of the handle is facing the patient's feet. It is reached by turning anticlockwise through 90° from the neutral position. The open position to the right is the opposite of the open position to the left. It is reached by turning clockwise through 90° from the neutral position. A further 90° rotation from the open position to the right can bring the handle in a position opposite to the neutral position.

CLASSIFICATION OF PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS

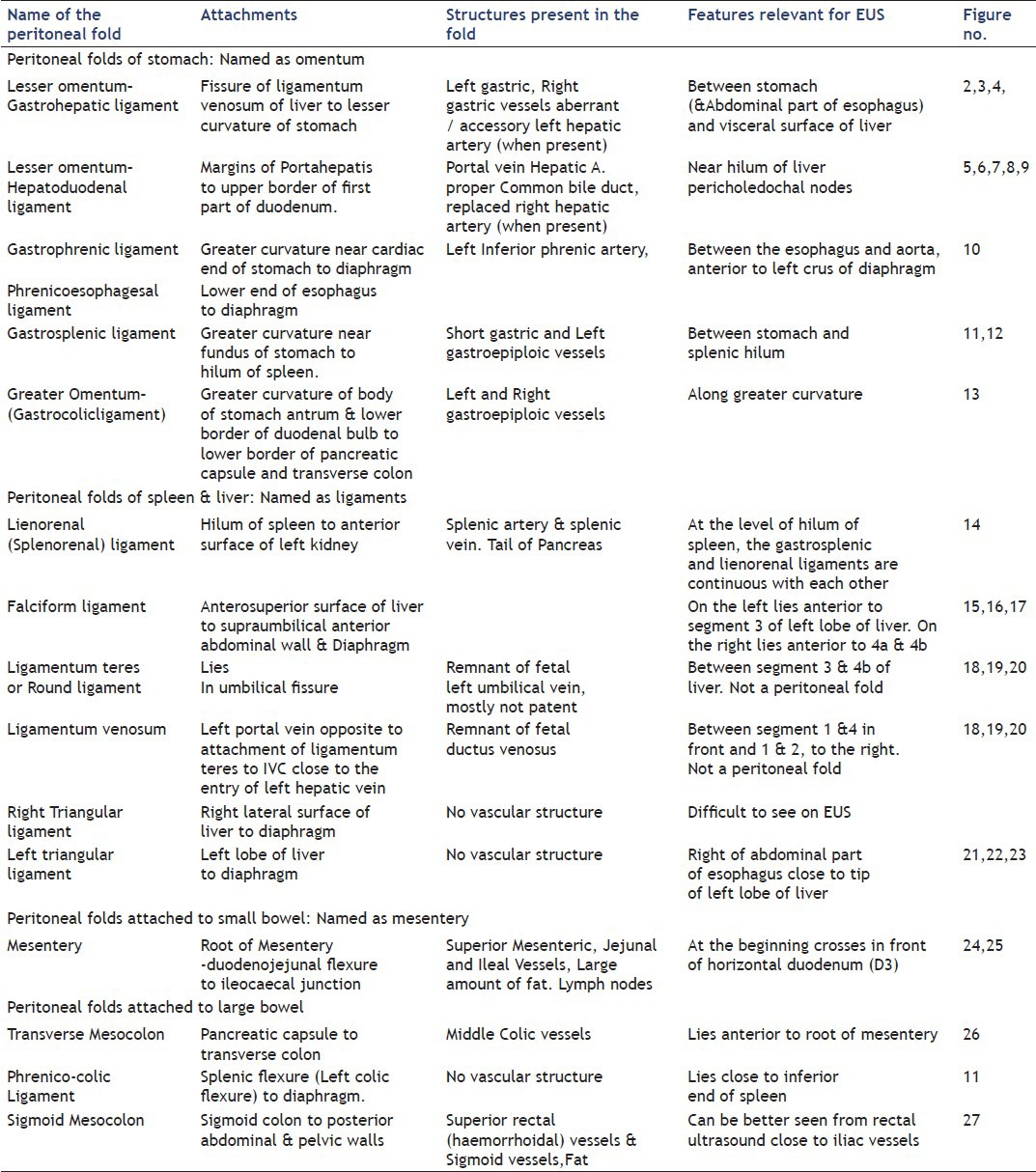

The peritoneal ligaments can be classified into the following groups [Table 1]

Table 1.

Peritoneal folds and structures present in them

Ligaments of the stomach

Ligaments of the liver and spleen

Ligaments attached to the small bowel

Ligaments attached to the large bowel.

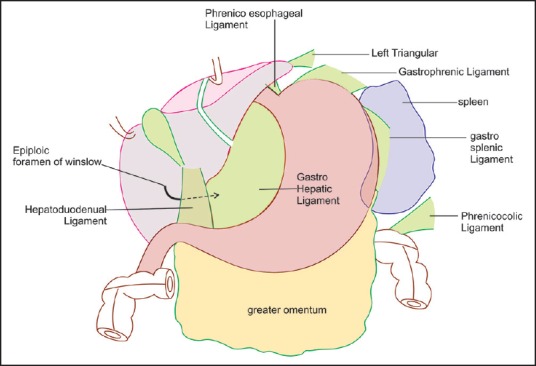

THE PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS OF THE STOMACH

The peritoneal ligaments of the stomach include two main groups: Ligaments attached to the lesser curvature which include the lesser omentum with gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligaments (HDLs) and ligaments attached to the greater curvature which include gastrophrenic, gastrosplenic ligaments and the greater omentum.

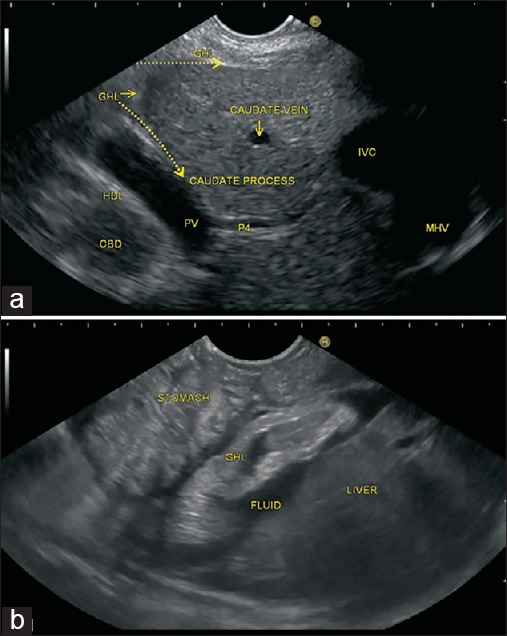

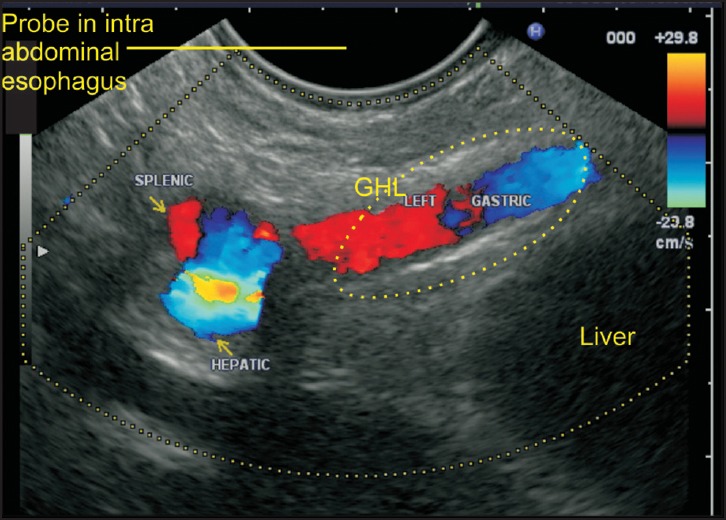

Anatomy of gastrohepatic ligament

Lesser omentum is a double-layered ligament that extends from its L-shaped attachment on the visceral surface of the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach (the gastrohepatic ligament [GHL]) and upper border of the first part of the duodenum (HDL). The GHL is identified at CT as a triangular fat-containing area between the stomach and liver. On US the hepatic artery and portal vein (PV) are identified in a parasagittal plane close to the right edge of the GHL. In the transverse axial plane near the level of the diaphragm, the GHL points to the intra-abdominal esophagus. On a transverse axial plane at the level of the pancreas the GHL spans the gap between the gastric body, antrum and liver, where it is commonly mistaken for retroperitoneal fat. The GHL divides the fluid into the greater peritoneal sac from fluid in the lesser peritoneal sac and the fluid touching the caudate lobe, posterior to the GHL lies in the superior recess of the lesser sac [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Gastrohepatic ligament (GHL) has an L-shape attachment to the liver. As it approaches the liver one of the limb runs on the under surface of the liver and goes towards the hepatoduodenal ligament whereas the other limb goes in the area between abdominal part of esophagus and liver where it is attached at the upper end to the fissure for ligamentum venosum. At the upper end of the fissure for ligamentum venosum, its anterior layer is continuous with left triangular ligament and its posterior layer is continuous with the inferior layer of the coronary ligament passing around the caudate lobe of the liver. At its attachment in liver, the GHL precisely divides the left portal vein into its two major segments the pars transversa and umbilical segments (ultrasound) and also divides the left lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe from the caudate lobe

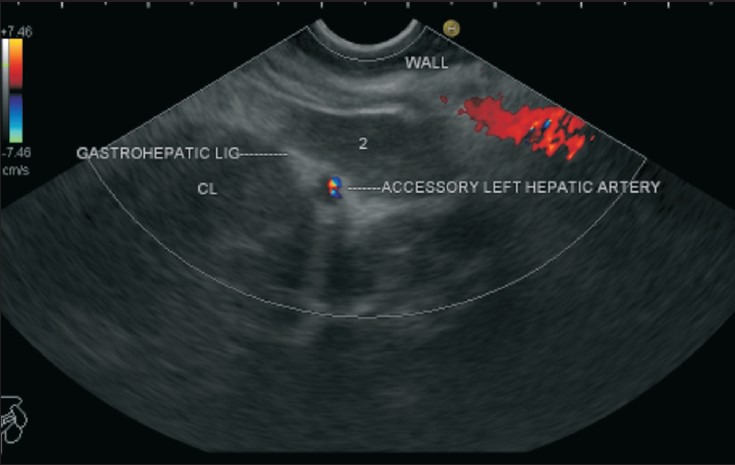

Technique of examination

The GHL occupies the area between the lower end of esophagus and liver and between the stomach and liver while imaging from stomach [Figure 2 and Video 1]. The hepatic artery is not a normal part of this ligament but when the left hepatic artery has an aberrant origin it enters the left lobe of the liver through the GHL into fissure for ligamentum venosum [Figure 3 and Video 2]. In a normal person, the left gastric artery enters this ligament near the lesser curvature of the stomach [Figure 4].

Figure 2.

(a and b) In this figure the two limbs of gastrohepatic ligament (GHL) are seen and one of the limb runs on the under surface of the liver, and the other limb goes in the area between abdominal part of esophagus and liver. The GHL is identified between the liver and the lesser curvature of the stomach. The GHL is seen lying between the liver and stomach. The presence of ascites is also noted

Figure 3.

The accessory or the aberrant left hepatic artery reaches the liver through the gastrohepatic ligament (GHL). In this case, the left hepatic artery is seen coursing through the GHL and then entering the ligamentum venosum enter the liver parenchyma

Figure 4.

Near the esophago-gastric junction, the gastrohepatic ligament (GHL) points to the intra-abdominal esophagus. In this image, the trifurcation of the celiac artery into its three branches is seen, and the left gastric artery is seen entering the GHL, which lies, between the intra-abdominal part of esophagus and liver

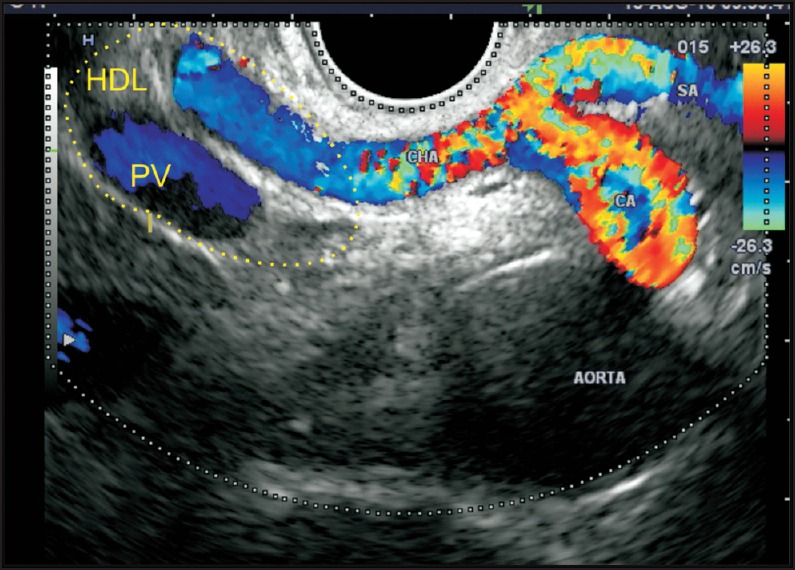

Anatomy of hepatoduodenal ligament

Liver has two surfaces: The diaphragmatic (anterosuperior) surface, which is smooth and convex, and the visceral (posteroinferior) surface which is flat and irregular. The HDL is a peritoneal fold enclosing the PV, hepatic artery and common bile duct on the visceral surface of the liver [Figure 1]. It can be evaluated from stomach and from duodenum.

Technique of examination from the stomach

Once the EUS probe lies in the stomach, the evaluation of the structures of the portal triad can be performed from the cardia or body of the stomach. When the scope is positioned near the body of the stomach, the celiac bifurcation can be identified, and the origin of the common hepatic artery and proper hepatic artery can be followed into HDL [Figure 5 and Video 3]. From the same location, the formation of PV can be followed-up from a caudal to cranial direction towards the hilum of the liver into HDL [Figure 6]. Alternatively when the scope is positioned near the cardia in an open position to the left a clockwise rotation provides transhepatic visualization of the liver hilum from where the portal triad and HDL can be followed in a craniocaudal direction.

Figure 5.

When the scope is positioned anterior to aorta the origin of the celiac artery and its bifurcation into two branches is seen. This bifurcation and the common hepatic artery are placed in a retroperitoneal location. As the common hepatic artery comes near the upper border of the pancreas near the portal vein, it enters the hepatoduodenal ligament. CA: Celiac artery, PV: Portal vein, HDL: Hepatoduodenal ligament, CHA: Common hepatic artery, SA: Splenic artery

Figure 6.

As the scope is positioned near the fundus of the stomach, it can see the inferior vena cava (IVC) and portal vein (PV) in the long axis. The IVC passes posterior to the hepatoduodenal ligament (HDL) while the PV exits from the upper border of the pancreas and enters the lower part of HDL. In this position, the bile duct is seen entering the ligament from the pancreas. In this position, the epiploic foramen can be imagined as a place between the IVC and PV just above the upper border of the pancreas

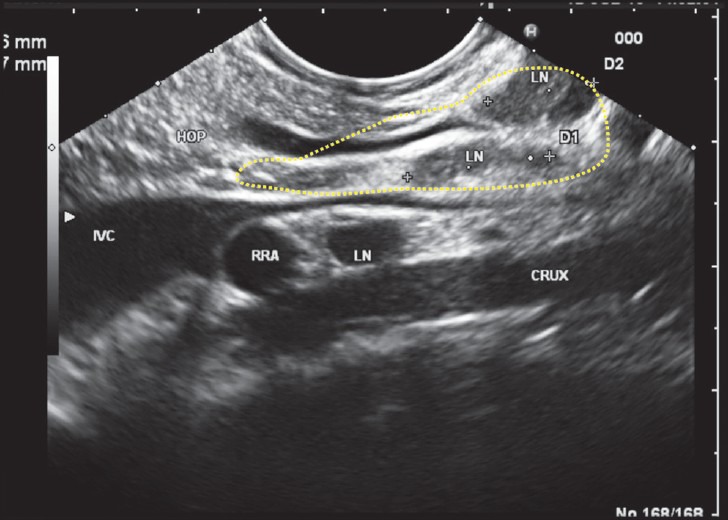

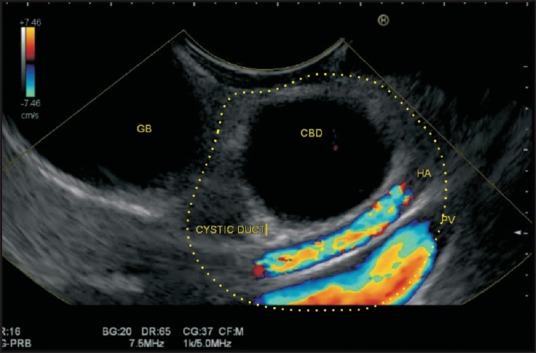

Technique of examination from the duodenal bulb

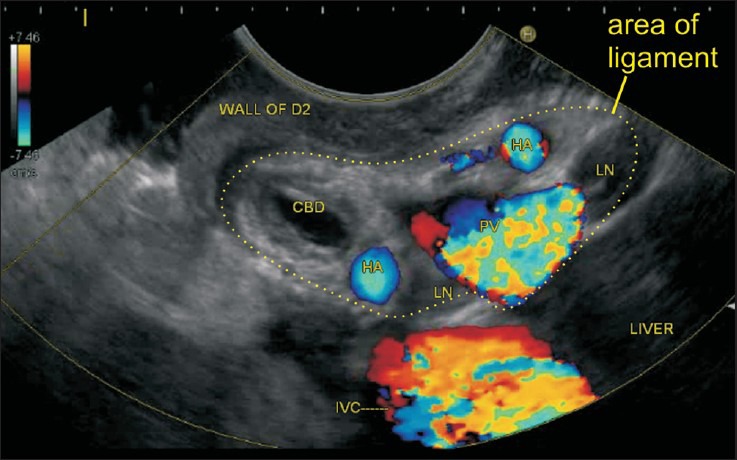

As the scope passes the pylorus it is pushed into the apex of the bulb, forming a J-shaped configuration. The scope tip is directed superiorly, and the probe faces posteriorly. A counter-clockwise rotation directs the scanning plane towards the liver hilum. In this position the HDL is located near the hilum where the structures of the portal triad are identified [Figures 7–9, Videos 4–6].

Figure 7.

As the scope passes into the second part of the duodenum and is shortened, an anticlockwise rotation takes the probe towards the hilum of the liver. In this position, the bile duct is demonstrated in a transverse axis along with cystic duct and gall bladder. The portal vein and hepatic artery are demonstrated in the long axis. All these structures shown lie in the hepatoduodenal ligament near the hilum except the gallbladder

Figure 9.

Once the scope is positioned in the second part of the duodenum, an anticlockwise rotation can trace the hepatoduodenal ligament near the liver hilum where the hepatic artery has already divided into right and left branches. Two-lymph nodes are also seen

Figure 8.

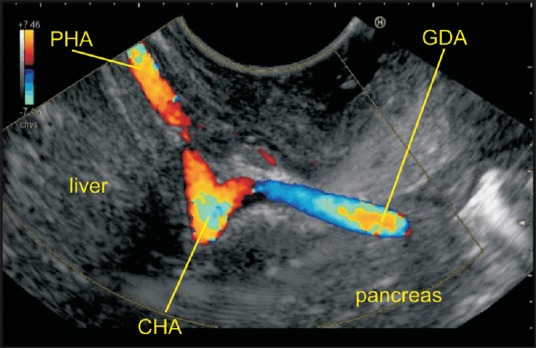

The common hepatic artery lies just outside the hepatoduodenal ligament and in this case the common hepatic artery is seen dividing into the hepatic artery proper and gastroduodenal artery. This division gives an appearance of vascular seagull when seen from duodenum. GDA: Gastro duodenal artery, PHA: Proper hepatic artery, CHA: Common hepatic artery

Anatomy of the gastrophrenic ligament and phrenicoesophageal ligament

The posterior surface of the esophagus and stomach are devoid of peritoneum close to the gastroesophageal (GE) junction and phrenicoesophageal ligament is attached to the posterior surface of the esophagus while the gastrophrenic ligament is attached to the posterior surface of the stomach. The attachment of the gastrophrenic ligament lies in apposition with the diaphragm, and frequently with the upper portion of the left suprarenal gland. The phrenicoesophageal ligament is a fascial expansion extending in a cone-like manner from the margins of the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm to the esophageal wall.

Technique of examination

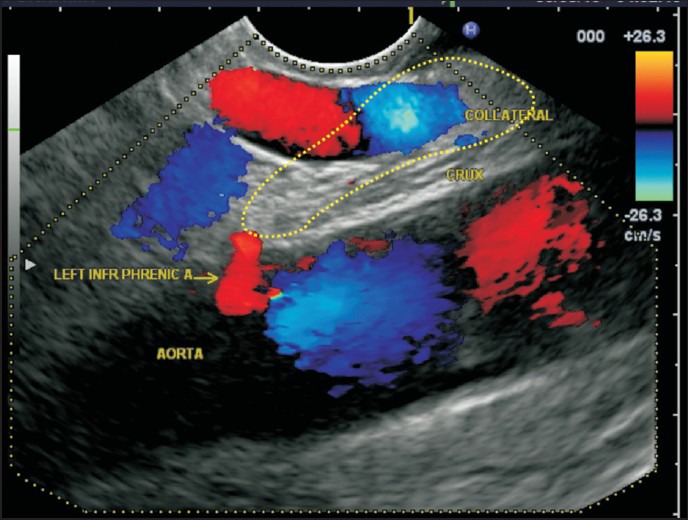

The examination of ligaments near cardia is performed by rotation of the EUS probe near the lower end of the esophagus and GE junction. The area between the aorta and esophagus anterior to crux of the diaphragm is occupied by the gastrophrenic ligament in which the left inferior phrenic artery or the posterior gastric artery (when present) can be sometimes seen [Figure 10 and Video 7].

Figure 10.

Most of the collaterals in portal hypertension are found within the ligaments. In this case, a collateral vein is seen between the esophagus and anterior to the crux of diaphragm and lies within the gastrophrenic ligament. The left inferior phrenic artery also enters this ligament close to esophago gastric junction

Anatomy of the gastrosplenic ligament

The gastrosplenic ligament is contiguous with the greater omentum and is derived embryologically from the dorsal mesogastrium. The gastrosplenic ligament connects the greater curvature of the stomach with the hilum of the spleen and contains short gastric vessels and left gastro-epiploic vessels.

Technique of examination

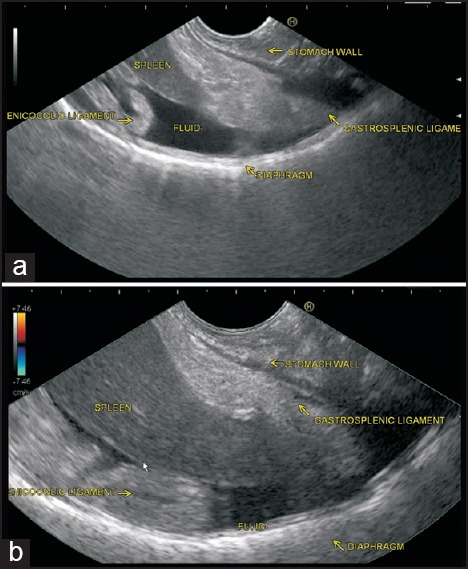

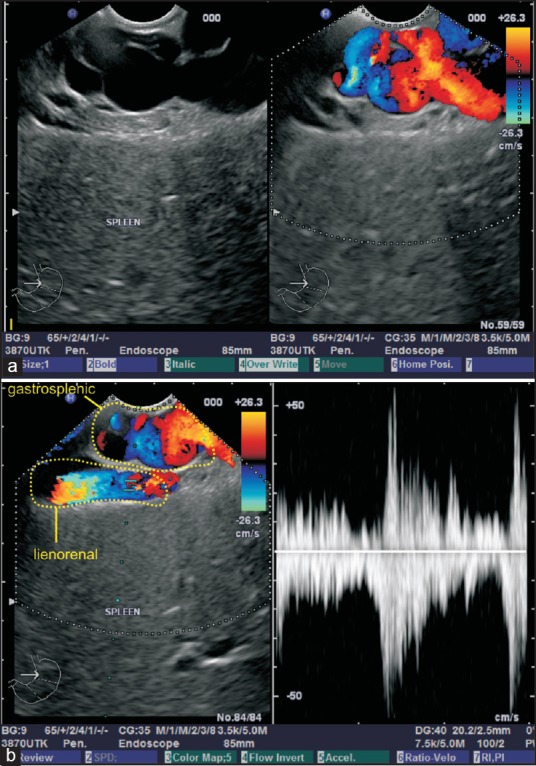

The gastrosplenic ligament is seen between the wall of the stomach and spleen [Figures 11 and 12 and Video 8].

Figure 11.

(a and b) The gastrosplenic ligament connects the greater curvature of the stomach with the hilum of the spleen. The gastrosplenic ligament is seen between the wall of the stomach and the lower pole of spleen. The phrenicocolic ligament is also seen beyond the lower pole of spleen. Both ligaments are floating because of the presence of ascitic fluid

Figure 12.

(a and b) The gastrosplenic ligament is seen between the wall of stomach and spleen. In this case, the collaterals are seen within the gastrosplenic ligament. Near the hilum of spleen, the gastrosplenic ligament and lienorenal ligament lie close together and in the image b the splenic artery is seen lying within the lienorenal ligament

Anatomy of the greater omentum

The greater omentum is a large apron-like fold of visceral peritoneum. It extends from the greater curvature of the stomach, and passes in front of the small intestine. It is composed of four layers of the peritoneum that hangs down like an apron from the greater curvature of the stomach and the proximal part of the duodenum, covering the small bowel, beneath the anterior abdominal wall and anterior to the transverse colon and small bowel. Its descending and ascending portions fuse to form a four-layer vascular fatty layer (the gastrocolic ligament).

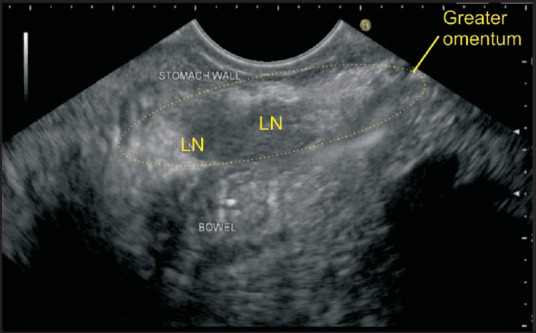

Technique of examination

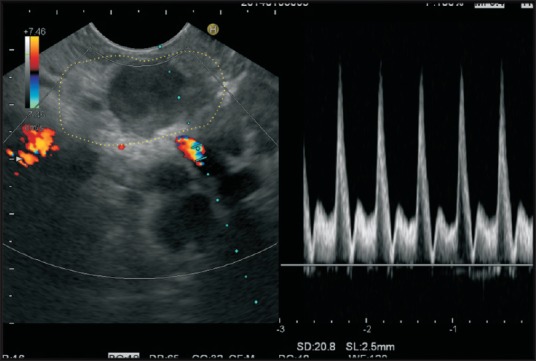

Presence of a large amount of fat in greater omentum shows it as a hyperechoeic layer along the greater curvature of the stomach. The presence of LNs and vessels can be easily appreciated. The presence of moving bowels of the small intestine is appreciated if the US waves are able to go through the hyperechoeic fatty layer of the greater omentum [Figure 13 and Video 9].

Figure 13.

The greater omentum passes in front of the small intestines beneath the anterior abdominal wall. In this image, the imaging is done from stomach, and greater omentum lies anterior to small bowel. Two lymph nodes surrounded by fat are seen in the greater omentum

PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS OF THE LIVER AND SPLEEN

The peritoneal ligaments of the liver include two main groups: suspensory ligaments of the liver and lesser omentum (gastrohepatic and HDL). The suspensory ligaments of the liver include the falciform, coronary and triangular ligaments. The peritoneal ligaments of spleen include gastrosplenic and lienorenal ligaments. The gastrohepatic, hepatoduodenal and gastrosplenic ligaments have been discussed above.

Anatomy of the lienorenal ligaments

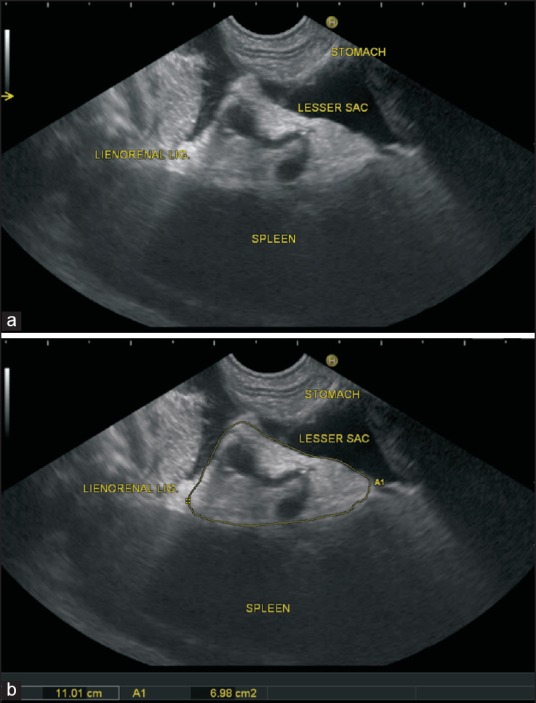

The lienorenal ligament lies between the left kidney and the spleen. The splenic vessels pass between its two layers. It contains the tail of the pancreas which is the only intraperitoneal portion of the pancreas.

Technique of examination

The lienorenal ligament is seen between the left kidney and spleen [Figure 14 and Video 10].

Figure 14.

The lienorenal ligament lies between the left kidney and spleen and contains the splenic artery and splenic vein. In this case, the lienorenal ligament is outlined

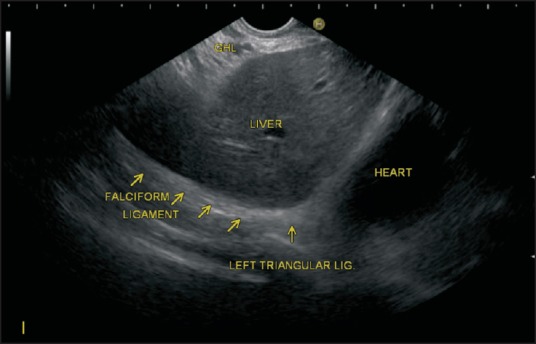

Anatomy of the falciform ligament

The falciform ligament is attached by its left margin to the under surface of the diaphragm and the posterior surface of the sheath of the right rectus as low down as the umbilicus. The posterior margin is free till it attaches to the notch on the anterior margin of the liver and then it extends back to the posterior surface [Figures 15 and 16].

Figure 15.

The falciform ligament attaches the liver to the anterior body wall. It is a broad and thin antero-posterior peritoneal ligament, its base being directed downward and backward and its apex upward and backward. It is situated in an antero-posterior plane but lies obliquely, so that one surface faces forward and is in contact with the peritoneum behind the right rectus and the diaphragm, while the other is directed backward and is in contact with the left lobe of the liver. As the falciform ligament approaches the diaphragm, it separates to surround the bare area of the liver. To the right, it is continuous with the superior layer of the right coronary ligament, which travels downward to form the right triangular ligament. To the left, it is continuous with the superior layer of the left coronary ligament, which is continuous with the left triangular ligament. The inferior layer of right coronary ligament is continuous with posterior layer and right leaf of the lesser omentum after passing in front of the groove for the inferior vena cava and then travels a half-circle course in front of the caudate lobe. The inferior layer of the left triangular ligament is continuous with the left leaf of the lesser omentum. IVC: Inferior vena cava

Figure 16.

The antero-superior surface of the liver lies farthest away from the screen in this image. The left lobe of the liver is identified in an open position to the left. The imaging of the left leaf of ligament is seen as a hyperechoeic structure between the surface of the liver and anterior rectus muscles. In this case, the ribs are seen

Technique of examination

The falciform ligament lies close to anterosuperior surface of the liver and is the farthest away from the screen during EUS. The imaging of the left leaf ligament is relatively easy in ectomorphic patients where the left lobe of the liver is identified as a triangular parenchymal structure in an open position to the left. In this situation, the ligament is seen as a hyperechoeic structure between the surface of the liver and anterior rectus muscle [Figure 17]. The falciform ligament is seen as a floating hyperechoic structure when surrounded by ascites [Figure 18]. The ligament can be followed along the anterior margin of the liver during clockwise rotation. As the clockwise rotation continues a notch is noted on the anterior margin of the liver where ligament dips into umbilical fissure as ligamentum teres [Figure 19, Video 11]. On further clockwise rotation, the right leaf of the falciform ligament can be seen in the same position but as larger amount of liver parenchyma of the right lobe appears between the probe and ligament, the examination of this part of the ligament may be difficult. A change to the lowest frequency may be helpful in visualizing the right leaf of ligament between the right lobe of the liver and the anterior abdominal wall muscles.

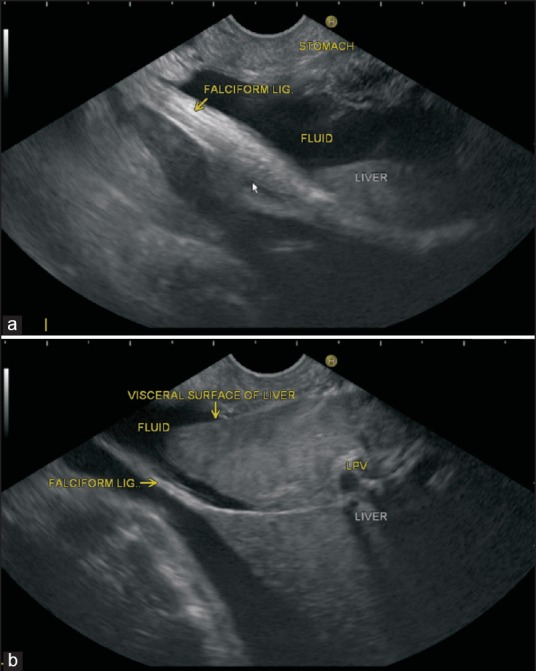

Figure 17.

(a and b) This patient has ascitis and in an open position on the left side the left lobe of the liver is seen. There is the presence of ascitis between the probe and liver. The falciform ligament is itself seen as a floating hyperechoic structure surrounded by ascites and is attached to the anterior margin of the liver. In one frame, the total thickness of ligament is seen while in another frame a thinner strip of ligament is shown in a and b

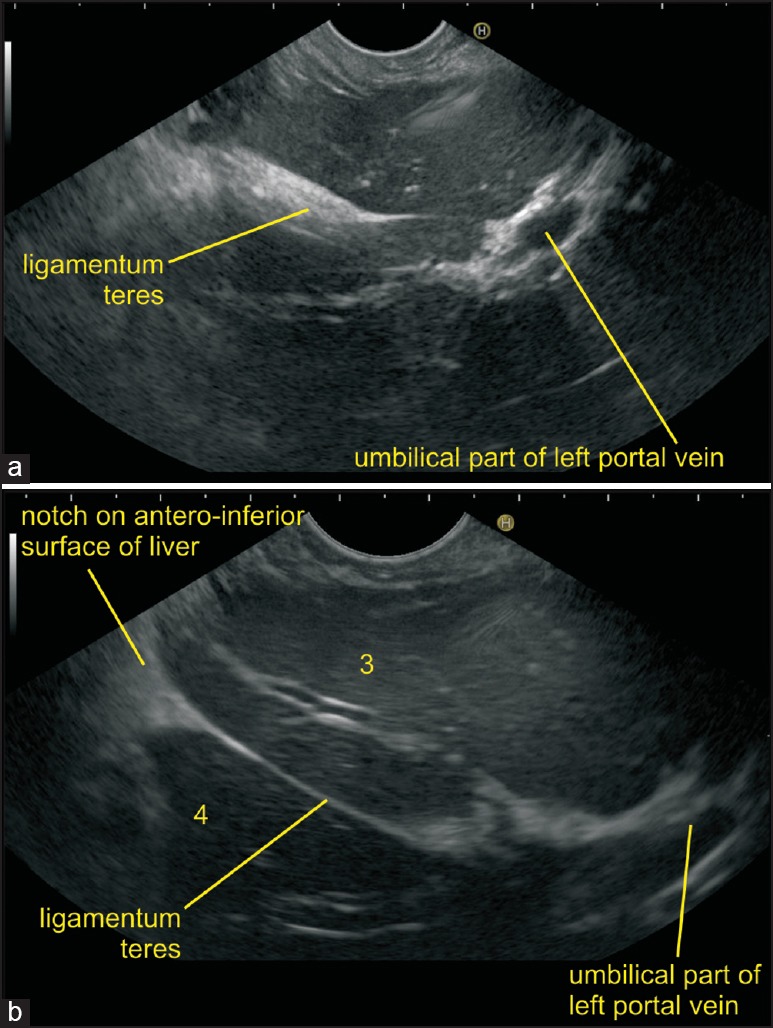

Figure 18.

(a and b) In this image the ligamentum teres is seen in two frames. (a) Multiple fibers in the form of a thick band are seen and (b) only a thin line of fiber is seen. On clockwise rotation from an open position facing the toes of patient the tributaries of the portal vein (PV) of segment 2 and 3 of the left lobe of the liver are seen to converge into the umbilical part of the LPV. The ligamentum teres, is seen as a hyperechoic band extending from the umbilical part of the LPV to the antero-superior liver surface. Use of the highest frequency with compound imaging and harmonics shows the separate fibers of the hyperechoic band

Figure 19.

Imaging of ligamentum teres from fundus of the stomach. The transition between the pars transversa and umbilical segments of left portal vein (PV) occurs at the point where the vessel's direction changes. In this image, it is identified as the hyperechoeic area where the tributaries of segment 2 and 3 of PV converge. The ligamenteum teres can be seen going away from the screen in this position, and the ligamentum venosum is seen going towards the probe. The presence of middle hepatic vein in this figure divides the liver lobe into three segments

Anatomy of the ligamentum teres

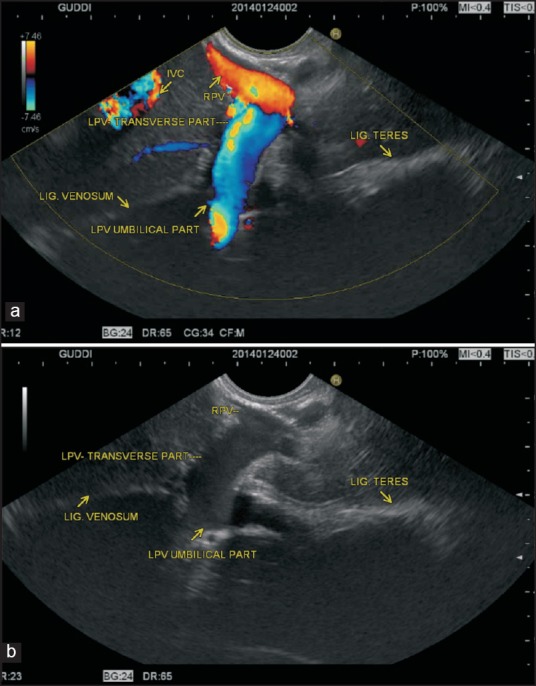

The left lobe is divided into medial (segment IV) and lateral sections or sectors (segments II, III) by the umbilical fissure, which is the main feature of the visceral surface of the liver. The ligamentum teres, which lies within the free margin of the falciform ligament, is located in umbilical fissure. The umbilical part of the left PV (LPV) remains surrounded on all sides (except the inferior surface where the umbilical fissure ends) by the liver parenchyma and continues into the transverse part of PV where it exits out of liver parenchyma. The deeper aspect of umbilical fissure contains the ligamentum teres which is attached to the LPV at the point where vessel's direction changes, and a transition occurs between the pars transversa and umbilical segments of the LPV. This change of direction always occurs at the top of the fissure for the LV. The ligamentum teres, a fibrous remnant of fetal left umbilical vein and the ligamentum venosum, the fibrous remnant of the ductus venosus are attached to the left branch of PV near the angulation.

Technique of examination

The technique of demonstration of the ligamentum teres from the notch in the anterior surface of the liver has been described above [Figures 18 and 19]. The other way to identify the ligament is by identifying the umbilical segment of PV and then following it toward the surface of the liver. It can be evaluated from the stomach and duodenum

Technique of examination from the fundus of the stomach

In an open position on the left side, the PV tributaries of segments 2 and 3 of the left lobe of the liver are identified. On clockwise rotation, the tributaries are seen to converge into the umbilical part of the LPV. The umbilical part of the LPV describes a smooth arch towards the ligamentum teres, which can be seen as a hyperechoic band extending from the umbilical part of the LPV to the anterosuperior liver surface. Use of the highest frequency with compound imaging and harmonics may show the separate fibers of the hyperechoic band. Pushing of scope towards the pyloric part of the stomach can follow the ligamentum teres from the umbilical fissure downwards towards the falciform ligament [Figure 18 and Video 12].

Technique of examination from the duodenal bulb

As the scope passes the pylorus, the PV is traced upwards to the hilum where its bifurcation can be seen with the right PV branch directed upwards, and the LPV branch directed downwards. The LPV is seen as an elongated structure going down vertically towards the umbilical fissure in the distance where it takes an L-shaped turn. The ligamentum teres can be seen from this position going from the junction of the transverse part and umbilical part of the LPV in a direction parallel to the probe [Figure 20 and Video 13].

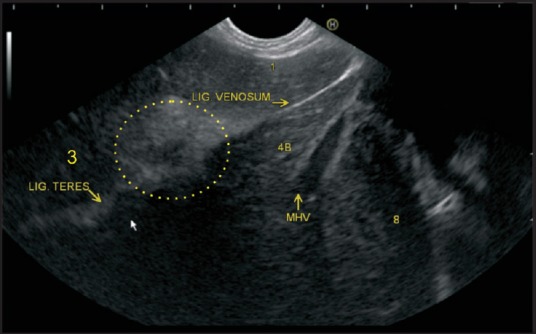

Figure 20.

(a and b) The imaging of ligamentum teres can be done from a duodenal bulb. The scope is positioned in the bulb and PV is traced to its bifurcation with the right PV branch directed upwards and the left branch downwards towards the umbilical fissure in the distance. The left PV (LPV) has two parts: Pars transversa and umbilical segments and at the junction of these two parts the direction of LPV changes. The ligamenteum teres is attached to this junction and is seen in a direction parallel to the probe. The ligamentum venosum is seen going away from the probe

Anatomy of the ligamentum venosum

Ligamentum venosum runs from the angle between the transverse and umbilical part of the LPV to the inferior vena cava (IVC) at the drainage of the left hepatic vein (HV) and middle HV. The ligamentum venosum is attached to the angle between the transverse and umbilical part of the LPV. It can be evaluated from the stomach and from the duodenum.

Technique of examination from the stomach

The ligamentum venosum demarcates the upper limit of the caudate lobe of the liver, which is bounded inferiorly by the ligamentum teres. On slight clockwise rotation from an open position to the left the posterior limit of the caudate lobe is identified by presence of the IVC [Figure 19].

Technique of examination from the duodenal bulb

The imaging of ligamentum teres helps in imaging of ligamentum venosum, which extends to the other side [Figure 20].

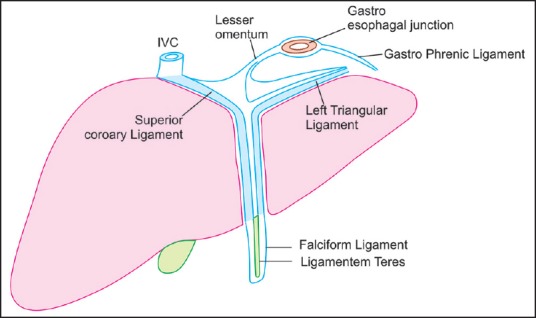

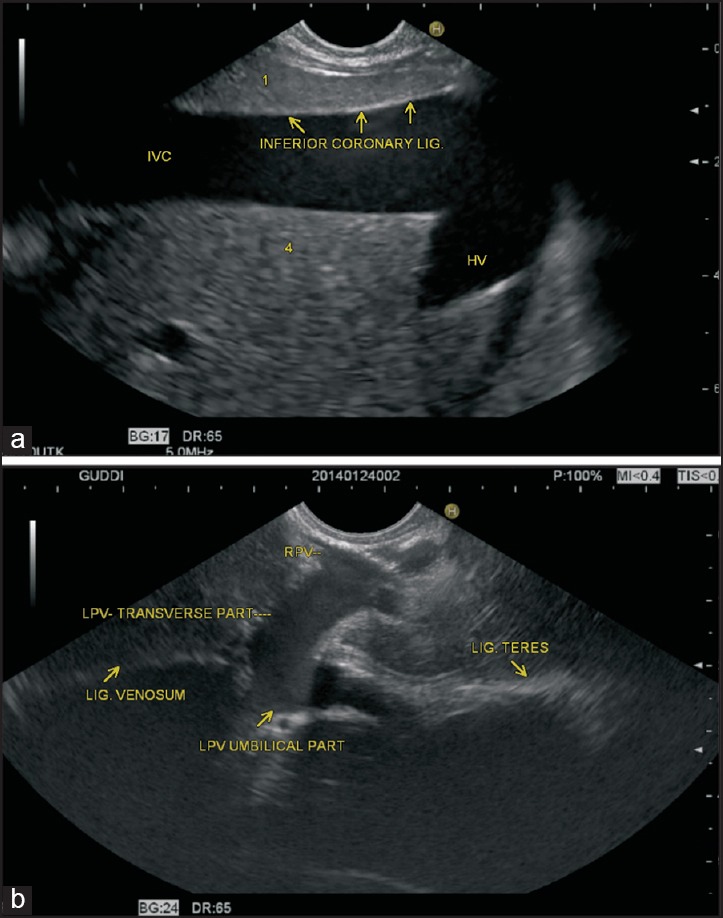

Anatomy of coronary and triangular ligament

As the falciform ligament approaches the diaphragm, it separates to surround the bare area of the liver. To the right, it is continuous with the superior layer of the right coronary ligament, which travels downward to form the right triangular ligament. To the left, it is continuous with the superior layer of the left coronary ligament, which is continuous with the left triangular ligament. The inferior layer of right coronary ligament is continuous with the posterior layer and right leaf of the lesser omentum after passing in front of the groove for the IVC and then travels a half-circle course in front of the caudate lobe. The inferior layer of the left triangular ligament is continuous with the left leaf of the lesser omentum. The right triangular ligament is formed by the fusion of the superior and inferior reflections of the right coronary ligament, and the left triangular ligament is formed by the fusion of the inferior and superior reflections of the left coronary ligament.

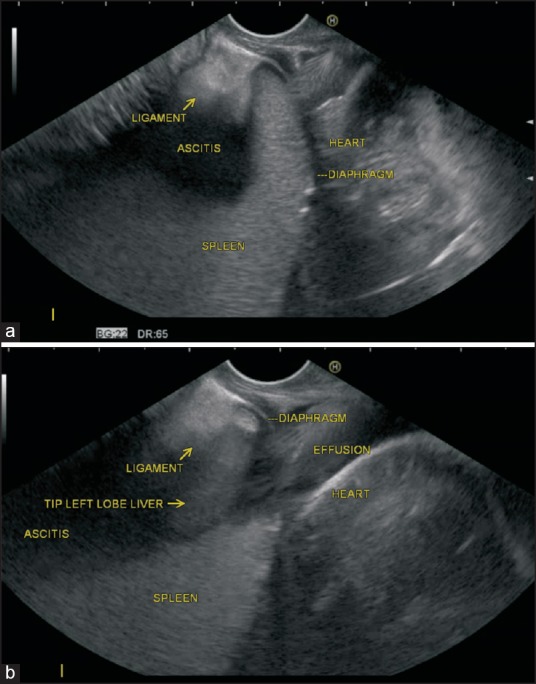

Technique of examination

Identification of the triangular ligaments is not possible by EUS easily. In the presence of ascites, the left triangular ligament can be identified between the left lobe of liver and diaphragm. The right triangular ligament is difficult to visualize [Figures 21–23 and Video 14].

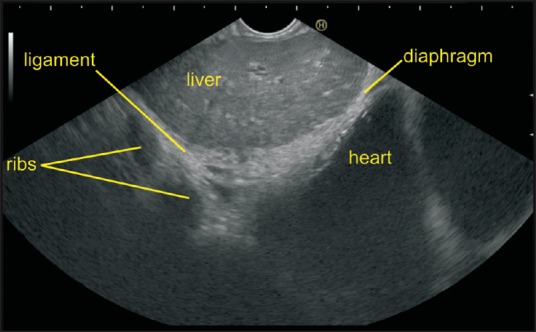

Figure 21.

The falciform ligament on the left is continuous with the superior layer of left coronary ligament, which is continuous with the left triangular ligament. In this case, the triangular ligament is seen in the area between liver and heart

Figure 23.

(a and b) At the upper end of the fissure for ligamenteum venosum, posterior layer of gastrohepatic ligament is continuous with the inferior layer of the coronary ligament after passing around the caudate lobe of the liver. In this case, the hyperechoeic line between the inferior vena cava and caudate of liver points to inferior coronary ligament. The upper end of the diaphragmatic surface is attached to the liver by left coronary ligament

Figure 22.

(a and b) As the falciform ligament approaches the diaphragm to the left, it is continuous with the superior layer of the left coronary ligament, which is continuous with the left triangular ligament. The inferior layer of the left triangular ligament is continuous with the left leaf of the lesser omentum. In this case, the ascitic fluid is present in the lesser omentum, and the left triangular ligament is seen between the tip of the left lobe of the liver and the spleen attached to the under surface of the diaphragm. The first image shows the tip of spleen and the second image shows the tip of the left lobe of the liver

PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS ATTACHED TO SMALL BOWEL

Anatomy of the mesentry

The mesentery proper refers to the peritoneum responsible for connecting the jejunum and ileum to the back wall of the abdomen. The line of attachment is called the root of mesentery, which is about 15 cm long. The root of the mesentery extends from the duodenojejunal flexure to the ileocecal junction and at the beginning crosses in front of horizontal duodenum from where it can be easily seen. It can be evaluated from the stomach and from the duodenum.

Technique of examination from the stomach

If at any time during the examination from the stomach the moving bowels are visualized, it indicates that the imaging is being done along the greater curvature of the stomach. In this situation, some part of the greater omentum and transverse mesocolon is almost always interposed between the greater curvature of the stomach and small bowel.

Technique of examination from the duodenum

When the probe is placed in the second part of the duodenum, it lies very close to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery, which is enclosed within the root of the mesentry [Figures 24 and 25, Video 15].

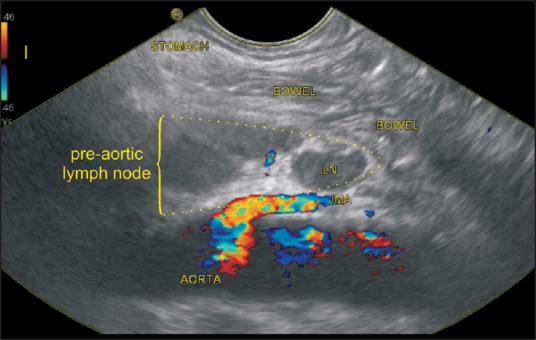

Figure 24.

The mesentery of small bowel is difficult to identify. In this case, the lymph node group is present in the pre-aortic fascia anterior to the aorta and inferior mesenteric artery. The small bowel mesentry is seen anterior to the group of node surrounding the bowel

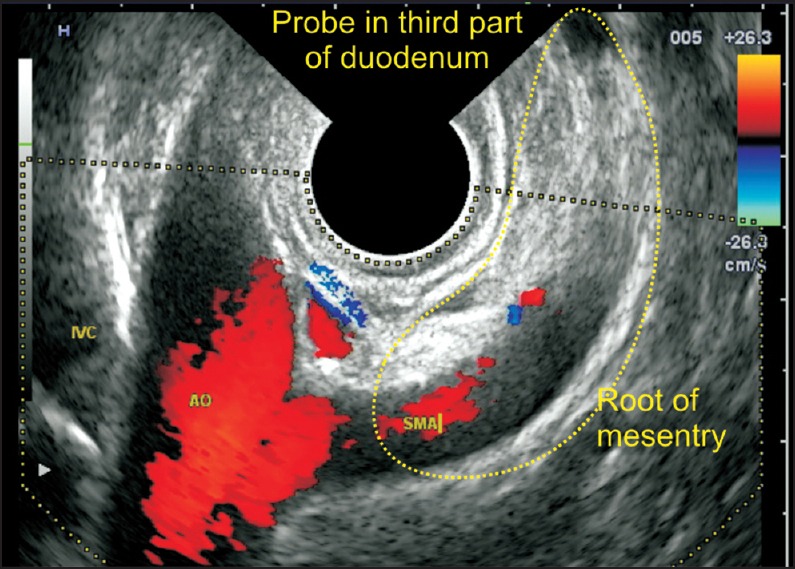

Figure 25.

The root of mesentery of small bowel extends from duodenojejunal flexure to the ileocaecal junction and at the beginning crosses in front of horizontal duodenum where it can be easily seen

PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS ATTACHED TO A LARGE BOWEL

Anatomy of the transverse mesocolon

The transverse mesocolon is a derivative of dorsal mesentery in the embryo and is a broad, fold of the peritoneum, which connects the transverse colon to the posterior wall of the abdomen. It is continuous with the two posterior layers of the greater omentum, which, after separating to surround the transverse colon, join behind it, and are continued backward to the vertebral column, where they diverge in front of the anterior border of the pancreas. This fold contains between its layers the middle colic vessels, which supply the transverse colon. It can be evaluated from the stomach and from the duodenum.

Technique of examination from the stomach

The transverse mesocolon contains a large amount of fat, and it is difficult to identify the structures which are lying within it and beyond it. The transverse mesocolon can be seen through the greater curvature of the stomach as a hyperechoeic structure in the area below the level of the pancreas where the LNs and the blood vessels of transverse mesocolon can be sometimes identified. Anatomically in this position the transverse mesocolon lies more close to the stomach wall whereas the greater omentum lies more close to the anterior abdominal wall but as these two structures are contiguous with each other it may be difficult to identify them separately.

Technique of examination from the duodenum

When the transducer is placed in the third part of the duodenum, the mesenteric vessels are identified in the root of the mesentry, which lies in a location inferior to pancreas. A clockwise rotation sweeps the direction of imaging from a plane lying inferior to the pancreas to a plane lying anterior to the pancreas where the transverse mesocolon is located. Identifying the course of feeding the vessel of the transverse mesocolon (the middle colic artery: the second branch from the right side of the superior mesenteric artery) is also helpful. The right side of the superior mesenteric artery is identified as the side lying towards the superior mesenteric vein in a horizontal portion of the duodenum [Figure 26, Videos 16 and 17].

Figure 26.

Imaging is done from duodenum and a clockwise rotation from the horizontal part of the duodenum after visualization of the mesenteric vessels traces the greater omentumlying anterior to the root of mesentry. In this case lymph nodes are seen within the greater omentum

Anatomy of the sigmoid mesocolon

The sigmoid mesocolon is a peritoneal ligament that attaches the sigmoid colon to the posterior pelvic wall and contains the superior hemorrhoidal and sigmoid vessels.

Technique of examination

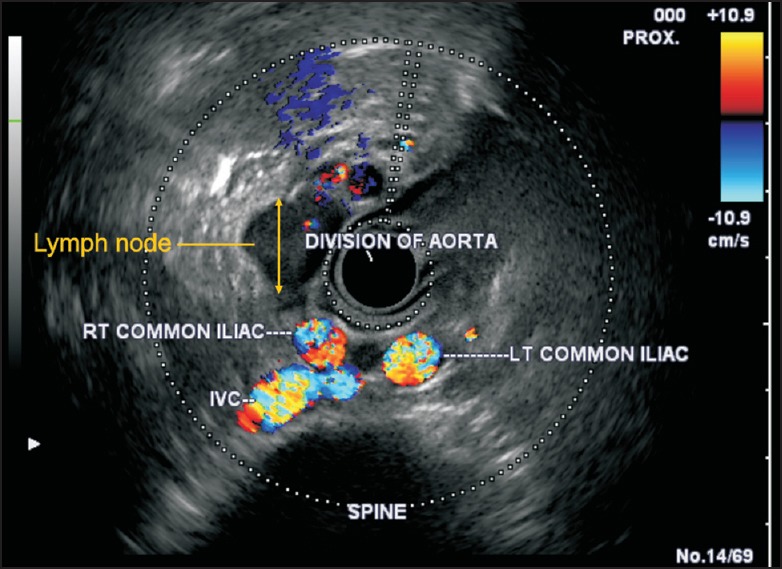

Insertion of echoendoscope for 20-25 cm distance in rectum will reach the sigmoid colon and usually allows visualization of the internal iliac vessels. The LNs surrounding the vessels are within the sigmoid mesocolon [Figure 27].

Figure 27.

Insertion of echoendoscope for 20-25 cm distance in rectum will reach the sigmoid colon and usually allows visualization of the internal iliac vessels. The lymph nodes surrounding the vessels are within the sigmoid mesocolon

Anatomy of the phrenicocolic ligament

The phrenicocolic ligament is seen near the lower pole of spleen and connects the colon with the left part of the diaphragm. A similar kind of supporting ligament is not found near the hepatic flexure. It separates the supramesocolic compartment from the left paracolic gutter [Figure 11].

Technique of examination

The phrenicocolic ligament is difficult to visualize in absence of ascites. When ascites is present, it can be seen near the lower pole of spleen close to the diaphragm.

DISCUSSION

Metastasis within ligament is of clinical importance as the peritoneal surface metastases are stage III and the liver metastases suggest stage IV disease. A better understanding of the location and normal appearance of ligaments by EUS is important for understanding the liver segmentation.[9] A systematic examination of ligaments can be a useful modality for imaging and can provide valuable information to the clinician. EUS of ligament is also useful for group staging of luminal malignancy; for sampling of station nodes; and for decision making regarding neoadjuvant therapy without laparoscopy/laparotomy. It has become essential that clinicians and endosonographers thoroughly understand the peritoneal spaces, the ligaments and mesenteries that form their boundaries in order to localize disease to a particular peritoneal space and formulate a differential diagnosis on the basis of that location.[10] In this article, we have attempted to describe the normal EUS anatomy of the peritoneal ligaments, which will be useful to understand the spread of disease processes.

Video Available on: www.eusjournal.com

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tirkes T, Sandrasegaran K, Patel AA, et al. Peritoneal and retroperitoneal anatomy and its relevance for cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics. 2012;32:437–51. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Kim TU, Lee JW, et al. The perihepatic space: Comprehensive anatomy and CT features of pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2007;27:129–43. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le O. Patterns of peritoneal spread of tumor in the abdomen and pelvis. World J Radiol. 2013;5:106–12. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i3.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healy JC, Reznek RH. The peritoneum, mesenteries and omenta: Normal anatomy and pathological processes. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:886–900. doi: 10.1007/s003300050485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auh YH, Lim JH, Kim KW, et al. Loculated fluid collections in hepatic fissures and recesses: CT appearance and potential pitfalls. Radiographics. 1994;14:529–40. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.3.8066268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoo E, Kim JH, Kim MJ, et al. Greater and lesser omenta: Normal anatomy and pathologic processes. Radiographics. 2007;27:707–20. doi: 10.1148/rg.273065085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vikram R, Balachandran A, Bhosale PR, et al. Pancreas: Peritoneal reflections, ligamentous connections, and pathways of disease spread. Radiographics. 2009;29:e34. doi: 10.1148/rg.e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai G, Filly RA. Sonographic anatomy of the gastrohepatic ligament. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:87–93. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia V, Hijioka S, Hara K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound description of liver segmentation and anatomy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:482–90. doi: 10.1111/den.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wigham A, Alexander Grant L. Preoperative hepatobiliary imaging: What does the radiologist need to know? Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2013;34:2–17. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.