Abstract

Treatment of patients with INTERMACS class I heart failure can be very challenging, and temporary long-term device support may be needed. In this article, we review the currently available temporary support devices in order to support these severely ill patients with decompensated heart failure. Strategies of using a temporary assist as a bridge to long-term device support are also discussed.

Keywords: heart failure, heart assist device, right heart dysfunction, cardiac risk factors, INTERMACS system

W. K. Abu Saleh, M.D.

Introduction

Providing acutely ill patients with temporary mechanical support can be a challenging task due to difficulty in patient selection and timing of device placement. On one hand, patients who require cardiopulmonary resuscitation for prolonged periods with no return of spontaneous circulation may be too sick for acute mechanical support. On the other hand, patients who can be medically managed with a short bridge of inotropes leading to recovery or transplant may not need mechanical support devices. Due to prolonged waiting times for cardiac transplantation and lack of suitable donors, the use of temporary assist devices have increased as waiting times on the transplant list have increased. However, placing acute support devices in patients with known pre-existing chronic heart failure who were candidates for cardiac transplantation can be challenging in that the patient, despite having acute mechanical support, still may have to wait an appreciable amount of time for an available organ. As further reviewed in this article, these temporary support devices are intended to be a temporary solution and most often serve as a bridge to recovery or to a more permanent device. In order to stratify acutely ill patients with heart failure, the Interagency Registry of Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) system has been developed (Table 1).1 The purpose of INTERMACS is to classify patients with heart failure and delineate them based on their degree of acuity or requirement for inotropic support and clinical status. The sickest patient would be in INTERMACS class I, commonly referred to as a “crash and burn” patient and typically profoundly ill on multiple pressors and inotropic agents. The less-sick heart failure patients are grouped in higher INTERMACS classes such as IV, V, and VI; these patients are usually medically managed outside the hospital but may require frequent hospital visits. As expected, patients with an INTERMACS profile of I are at highest risk for poor outcome, and their mortality can be as high as 50% even with significant support. These higher acuity patients are the candidates that may be served by placement of a temporary ventricular assist device (VAD).2 Due to the heterogeneity in patient profiles presenting with INTERMACS 1 and heterogeneity in the care provided at different institutions, there is a paucity of data to guide clinicians on what is the best type of short term device, ideal duration of support and best exit strategy for an individual patient.

Table 1.

INTERMACS Profiles of Limitation at Time of Implant

Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

One of the easiest and simplest devices to place—whether at the bedside or the cardiac catheterization lab—is the intraaortic balloon pump (IABP). The IABP is a polyethylene balloon mounted on a catheter, which is inserted into the aorta through the femoral artery in the leg and guided into the descending aorta approximately 2 cm from the left subclavian artery. The net effect is to decrease systolic aortic pressure by as much as 20% and increase diastolic pressure.3 At the start of diastole, the balloon inflates, augmenting coronary perfusion. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation is a method of temporary mechanical circulatory support that attempts to create a more favorable balance of myocardial oxygen supply and demand by using the concepts of systolic unloading and diastolic augmentation. There are absolute and relative contraindications concerning IABP usage, with the absolute contraindication being significant aortic regurgitation or aortic dissection. Relative contraindications include severe peripheral vascular disease, presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm or stents in the iliac arteries, or severe coagulopathy, all of which may preclude pump insertion.

Intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation remains the workhorse of mechanical circulatory support used for decompensated heart failure patients. It is considered by some to be the first line therapy of decompensated heart failure and is the first support device placed in the majority of patients who present to the heart failure practice. If the patient's heart failure does not improve with balloon pump intervention, the patient will most likely require a more definitive mechanical support therapy.

Continuous-Flow Devices

Continuous-flow pumps have a continuously spinning rotor or impeller that produces forward flow by pulling blood from the ventricle and ejecting it into the arterial system, typically the proximal aorta. The pump operates at a speed set by the clinician, with higher speeds delivering more flow.4 The two types of continuous-flow devices are axial and centrifugal flow. Axial flow pumps have an impeller in the same axis as the blood flow that accelerates blood and provides flow. Centrifugal pumps have a rotor that is suspended by a fluid layer or magnetically levitated within an outer casing.5

Impella (2.5 and 5.0)

The Impella® systems (Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) are a set of percutaneously placed microaxial VADs used to provide rapid, short-term support during high-risk percutaneous interventions, acute heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or during/after cardiac surgery.6 They are inserted retrograde across the aortic valve, with the caged inlet within the left ventricular (LV) cavity and the outflow in the ascending aorta. Blood is aspirated by an electrically driven motor from the left ventricle and pumped into the aorta.

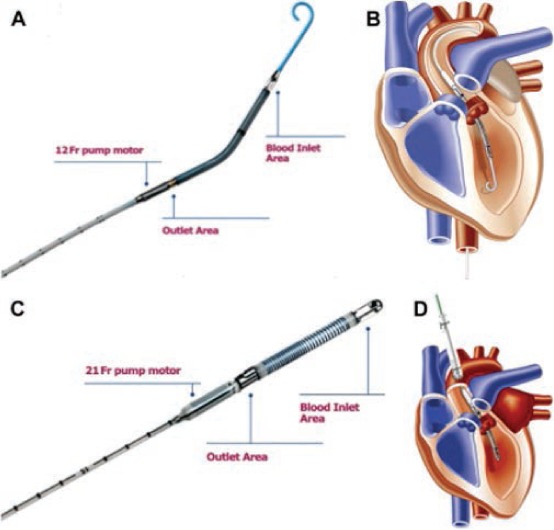

The Impella Recover LP 2.5 (Figure 1 A, B) is the smallest of the microaxial flow temporary VADs. It is inserted through a 12-Fr femoral artery sheath and can generate up to 2.5 L/min of flow.5 The Impella LD 5.0 is available for percutaneous delivery or via a vascular graft and provides up to 5.0 L/min of flow. The Impella Recover LP 5.0 is a larger version of the LP 2.5 that is inserted through a 21-Fr sheath and requires surgical cut down of the femoral artery for placement. The LD (Figure 1 C, D) is inserted directly into the ascending aorta through a 10-mm vascular graft.8

Figure 1.

(A) Impella LP 2.5 pump. (B) Impella LP 2.5 inserted from femoral artery across aortic valve. (C) Impella LD pump. (D) Impella LD inserted through ascending aorta. Courtesy of Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA; with permission.

There is now clinically available a more powerful Impella heart pump in the U.S., the 4L/min Impella CP (Cardiac Power). In Europe the device is known as Impella cVAD and it's been cleared with a CE Mark in April of this year. The Impella CP is built on the same foundation as the Impella 2.5, but provides more than a 50% increase in pumped blood volume, extending the technology for use to more acute patient cases.

The Impella cannot be used in patients with heavily calcified or prosthetic aortic valves. Although severe aortic regurgitation is not an absolute contraindication, it will reduce the effectiveness of the pump.9 Severe peripheral vascular disease may preclude femoral insertion.6,8,10

Major complications of the Impella system include hemolysis, bleeding, limb ischemia (peripheral insertion), device malpositioning, endocardial or valvular injury caused by suction events, thromboembolism, and infection. These devices received 510(k) clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in June 2008 for providing up to 6 hours of partial circulatory support. In Europe, the Impella 2.5 is approved for use up to 5 days. Reports of longer duration of therapy in both the United States and Europe have been published.11,12

TandemHeart

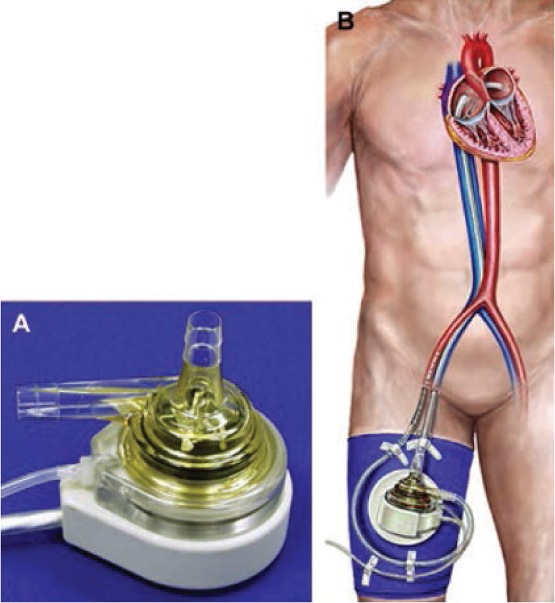

The TandemHeart™ (CardiacAssist, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) is a percutaneous centrifugal pump (Figure 2) that houses a 6-blade rotor which can generate up to 5.0 L/min at 7500 rpm. The inflow cannula is a 21-Fr polyurethane tube with an end hole and multiple side holes that are inserted through the femoral vein into the left atrium via a transseptal puncture approach. Blood is returned to patients by the outflow cannula (either one 17-Fr cannula or two 15-Fr cannulas connected to a Y catheter) in the contralateral femoral artery, although insertion via the axillary artery and vein has also been reported.13 Complications associated with the transseptal puncture include perforation of the aortic root, coronary sinus, or posterior right atrial free wall.14 Long-term disposition of the transseptal puncture is unknown, but the majority of echocardiographic studies have not shown any significant left-to-right shunting after removal of the transseptal catheter.15 Widespread use of the TandemHeart has been limited by the need for transseptal placement of the inflow catheter, which, if not done during cardiovascular surgery, requires the expertise of trans-septal puncture by an electrophysiologist or interventional cardiologist.9

Figure 2.

(A) TandemHeart pump. (B) TandemHeart system. Courtesy of CardiacAssist, Inc., Pittsburg, PA; with permission.

The TandemHeart is contraindicated in patients with large ventricular septal defects due to the risk of hypoxemia caused by right-to-left shunting with LV unloading. Severe peripheral vascular disease may prevent TandemHeart insertion.16 The intended use of the TandemHeart left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is to provide temporary mechanical support and complete unloading of the left heart. The device provides short-term support from a few hours up to 14 days, until the heart can be bridged to recovery or a more permanent LVAD.17 Additionally, the TandemHeart can be used in a temporary fashion during high-risk cardiac catheterization procedures including high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention, and it can also be used as a temporary right ventricular assist device and is placed percutaneously as well.18

Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

In venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO), the drainage cannula is commonly placed in the inferior vena cava (IVC) or right atrium (RA). This can be done either via a sternotomy or percutaneously by inserting the cannula through the internal jugular or the femoral vein. Blood is returned to the patient through a cannula inserted in either the ascending aorta (central ECMO, inserted surgically) or the femoral artery (peripheral ECMO, inserted either surgically or percutaneously). Central ECMO is a preferred option when used immediately after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) as the location of the cannulae is similar to the ones used during surgery and the chest is open for easy access and cannulation.

VA ECMO support decreases cardiac work and reduces cardiac oxygen consumption. It also provides adequate systemic organ perfusion with oxygenated blood because the oxygen present in the ECMO circuit provides adequate tissue oxygenation regardless of the underlying lung function.

If cardiac recovery is expected, it is important to reduce distension of the ventricles; VA ECMO can achieve this if the left ventricle continues to eject or a drainage catheter is inserted directly into the left ventricle.

Whether a peripheral or central ECMO, these circuits are usually placed in patients who are in extremis or undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The peripheral VA ECMO circuit is the one that can be placed the most quickly. However, with the drawbacks of leg ischemia and inability to unload the left ventricle, it is intended to be a short-term acute device and often requires transition to another temporary device in profoundly ill patients who are unlikely to recover cardiac function.

Another commonly used indication for ECMO support is in patients who have undergone a recent cardiac surgery and have developed post-cardiotomy shock. Because the chest is still open, the transition to a central ECMO is easily done, and a left-ventricular vent can also be placed to unload the left ventricle. The goal of central ECMO in this setting is to allow time for the patient's heart to recover and thus allow explantation of the central device. However, as in other indications of ECMO placement, patients who do not recover their cardiac function may need to be bridged to another temporary or more permanent device.

CentriMag/BioMedicus Centrifugal Pumps

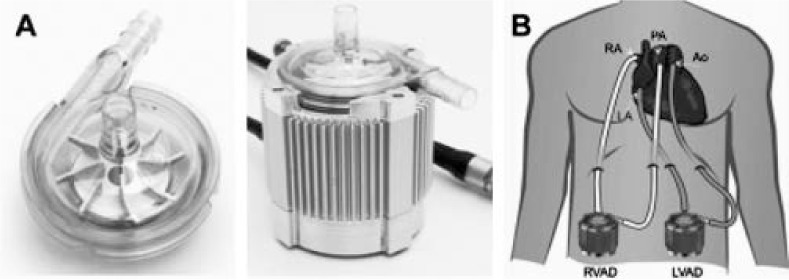

The CentriMag® pump (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA) (Figure 3 A) and the BPX-80 Bio-Pump® Plus centrifugal pump (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) are surgically implanted centrifugal pumps with a bearingless, magnetically levitated rotor. These pumps are specifically designed for extracorporeal circulatory support applications, such as CPB or used as an ECMO circuit, or for a temporary ventricular assist device.19 The pump has no contact between the impeller and the rest of the pump components; therefore, it creates a frictionless motor that does not generate heat or wear of the components, which leads to lower rates of hemolysis and pump thrombosis.7 The pump can provide up to 10 L/min of flow and is intended for up to 14 days of support.9 A console displays the pump's rotational speed and flow rate (Figure 3 B). Although insertion is usually via a sternotomy, peripheral cannulation through the femoral artery and vein has also been reported.20 If full cardiopulmonary support is needed, an oxygenator can be added to the circuit to adapt it for ECMO.21

Figure 3.

(A) CentriMag pump and pump with motor. (B) Common CentriMag cannulation configurations for univentricular or biventricular support. Ao: aorta; LA: left atrium; LVAD: left-ventricular assist device; PA: pulmonary artery; RA: right atrium; RVAD: right-ventricular assist device. Courtesy of Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA; with permission.

Both of these centrifugal pumps can provide right-ventricular or left-ventricular support depending on the cannulation involved. They can be used together for biventricular support as well, using the combination of left and right heart cannulation strategies. Since these devices commonly require a sternotomy, and patients often undergo delayed sternal closure, there is always a risk of bleeding and infection. Other concerns regarding use of these extracorporeal pumps are the effects on the patient's coagulation cascade, rate of hemolysis, and platelet dysfunction.19

Discussion

There are multiple options available to the patient in acute cardiogenic shock or INTERMACS class I status. The clinician may be limited in the selection of devices depending on the patient's clinical status, availability of the device, and the time needed to place the device. For example, patients requiring open surgical placement of devices usually needs time to get to the operating room, whereas a patient in extremis requires immediate device support.

Devices that are placed in the cardiac catheterization lab, such as the Impella 2.5 and TandemHeart, can provide unloading of the left ventricle, although the smaller Impella only results in partial unloading. The TandemHeart does require a transseptal puncture, which requires a skilled practitioner and fluoroscopy. Intra-cardiac ultrasound or transesophageal echocardiography are used at some centers to guide the transseptal puncture or cannula placement. The Impella can be placed under simple fluoroscopic guidance and can provide partial support, or it can provide full support if the larger Impella is placed through an arterial conduit. Choice of device depends on clinician experience and preference and stability of the patient. The need for a biventricular support may necessitate a more aggressive approach, including open surgery. In order to adequately unload both ventricles, it may be necessary to place separate CentriMag or centrifugal pumps in an extracorporeal manner. Since these pumps are placed during surgery and often require an open chest, they may be limited in their ability to provide long-term support. Recovery from temporary biventricular support is rare, and more often than not the patient will require a bridge to a more permanent biventricular solution that could include a bilateral Thoratec Paracorpeal Ventricular Assist Device™ or SynCardia total artificial heart (SynCardia Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ). Additionally, if appropriately stabilized by the acute device intervention, the patient may be considered for cardiac transplantation. There are isolated reports in the literature of patients bridged to cardiac transplantation successfully from acute support devices.22–24 However, with the challenges of donor availability and the nature of this high-risk procedure, it may not be feasible to proceed directly to cardiac transplantation.

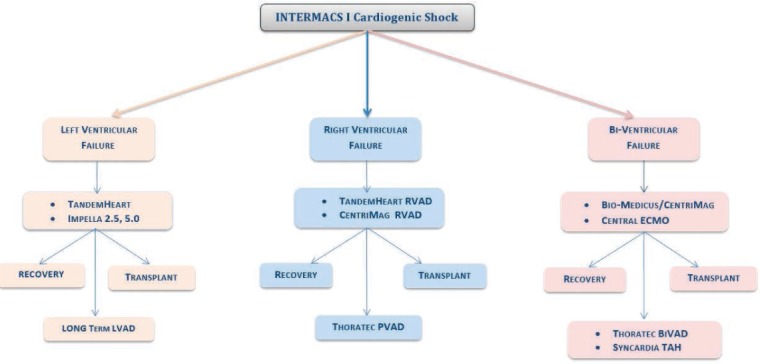

These acute devices are intended to be used in a temporary manner and not as a long-term solution. There are extracorporeal devices that are temporary in nature and placed through groin cannulation or even through open chest. All of these devices require systemic anticoagulation that can increase the risk of bleeding; additionally, access to the arteries can lead to arterial injuries including dissection, ischemic extremities, and even limb loss. Figure 4 provides a summary of our approach to patients with isolated left-ventricular failure, right-ventricular failure, and biventricular failure.

Figure 4.

Treatment approach to patients with isolated left ventricular failure, right ventricular failure and bi-ventricular failure.

Conclusion

Since the first clinical LVAD was implanted in 1963 as salvage therapy for postcardiotomy shock,25 temporary mechanical support has become a routine bridge to recovery or other long-term therapies in patients with cardiogenic shock. It is hoped that advances in device design and patient selection will result in further improvements in outcomes and reductions in adverse events.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

Funding/Support: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Stevenson LW, Couper G. On the fledgling field of mechanical circulatory support. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007 Aug 21;50(8):748–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Miller MA, Timothy Baldwin J, Young JB. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014 Jun;33(6):555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urschel CW, Eber L, Forrester J, Matloff J, Carpenter R, Sonnenblick E. Alteration of mechanical performance of the ventricle by intraaortic balloon counterpulsation. Am J Cardiol. 1970 May;25(5):546–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen DM. Physiology of continuous-flow pumps. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2012 Jan–Mar;23(1):46–54. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e31824125fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teuteberg JJ, Chou JC. Mechanical circulatory devices in acute heart failure. In: Desai S, Puri N, editors. Cardiac Emergencies in the ICU, An Issue of Critical Care Clinics. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2014 Jul.. p. 588. p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza CF, de Souza Brito F, De Lima VC, De Camargo Carvalho AC. Percutaneous mechanical assistance for the failing heart. J Interv Cardiol. 2010 Apr;23(2):195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers TJ. Temporary ventricular assist devices in the intensive care unit as a bridge to decision. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2012 Jan–Mar;23(1):55–68. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e318240e369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziemba EA, John R. Mechanical circulatory support for bridge to decision: which device and when to decide. J Card Surg. 2010 Jul;25(4):425–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2010.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koerner MM, Jahanyar J. Assist devices for circulatory support in therapy-refractory acute heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008 Jul;23(4):399–406. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328303e134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garatti A, Russo C, Lanfranconi M et al. Mechanical circulatory support for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: an experimental and clinical review. ASAIO J. 2007 May–Jun;53(3):278–87. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318057fae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber DM, Raess DH, Henriques JPS, Siess T. Principles of Impella cardiac support: the evolution of cardiac support technology toward the ideal assist device. Card Interv Today. 2009 Jun–Jul;(Suppl):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriques JPS, Remmelink M, Baan J, Jr et al. Safety and feasibility of elective high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention procedures with left ventricular support of the Impella Recover LP 2.5. Am J Cardiol. 2006 Apr 1;97(7):990–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anyanwu AC, Fischer GW, Kalman J, Plotkina I, Pinney S, Adams DH. Preemptive axillo-axillary placement of percutaneous transseptal ventricular assist device to facilitate high-risk reoperative cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010 Jun;89(6):2053–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman PA, Munger TM, Torres N, Rihal C. Percutaneous endocardial and epicardial ablation of hypotensive ventricular tachycardia with percutaneous left ventricular assist in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007 Jan;18(1):106–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiele H, Smalling RW, Schuler GC. Percutaneous left ventricular assist devices in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2007 Sep;28(17):2057–63. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aragon J, Lee MS, Kar S, Makkar RR. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device: “TandemHeart” for high-risk coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005 Jul;65(3):346–52. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckner BA, Jacob LP, Gregoric ID et al. Clinical experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device as a bridge to cardiac transplantation. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35(4):447–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prutkin JM, Strote JA, Stout KK. Percutaneous right ventricular assist device as support for cardiogenic shock due to right ventricular infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008 Jul;20(7):E215–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshi H, Shinshi T, Takatani S. Third-generation blood pumps with mechanical noncontact magnetic bearings. Artif Organs. 2006 May;30(5):324–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgerald D, Ging A, Burton N, Desai S, Elliott T, Edwards L. The use of percutaneous ECMO support as a ‘bridge to bridge’ in heart failure patients: a case report. Perfusion. 2010 Sep;25(5):321–5. 327. doi: 10.1177/0267659110378387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz TA, Singh G, Popjes E et al. Initial experience with CentriMag extracorporal membrane oxygenation for support of critically ill patients with refractory cardiogenic shock. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010 Jan;29(1):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kar B, Adkins LE, Civitello AB et al. Clinical experience with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(2):111–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra D, Kar B, Idelchik G et al. Usefulness of percutaneous left ventricular assist device as a bridge to recovery from myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2007 Jun;99(12):1755–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Francesca S, Palanichamy N, Kar B, Gregoric ID. First use of the TandemHeart percutaneous left ventricular assist device as a short-term bridge to cardiac transplantation. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(4):490–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liotta D, Hall CW, Henly WS et al. Prolonged assisted circulation during and after cardiac or aortic surgery. Prolonged partial left ventricular bypass by means of intracorporeal circulation. Am J Cardiol. 1963 Sep;12:399–405. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(63)90235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]