Abstract

The status of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Saudi Arabia (SA) was examined from various perspectives based on a systematic literature review and the authors’ personal experiences. In this regard, database and journal search were conducted to identify studies on RA in SA, yielding a total of 43 articles. Although efforts have been made to promote RA research in SA, current studies mostly represent only a few centers and may not accurately portray the national status of RA care. Notably, biological therapies were introduced early for almost all practicing rheumatologists in SA (government and private). However, no national guidelines regarding the management of RA have been developed based on local needs and regulations. Also, while efforts were made to establish RA data registries, they have not been successful. Taken together, this analysis can contribute to the planning of future guidelines and directives for RA care in SA.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that usually occurs in middle-aged individuals and leads to tissue destruction in the synovial joints (for example, hands, wrists, knees). Although RA manifestation includes pain, stiffness, swelling, and functional impairment, it can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages, as its symptoms can closely mimic other diseases.1 Moreover, clinical management of RA can be complicated by the fact that it represents a variable disease that exhibits differential therapeutic responses.2 For this reason, ongoing investigation into the origin of patient variability and ways to enhance RA management/treatment are essential for improving the current level of clinical care provided by rheumatologists. There are several methods presently employed for RA diagnosis and monitoring of therapeutic outcomes,3 such as direct examinations, and more sophisticated imaging technologies (for example, ultrasound).4 Following diagnosis, therapy for RA focuses on controlling symptoms to prevent further joint damage. In this regard, RA is commonly treated using disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and/or biological therapies (for example, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-a]).3 Notably, the study of the differential utilization of these management options in various centers or regions, as well as the way in which distinct clinical practices can influence the efficacy of diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment strategies, can yield insight into effective treatment options for RA patients. To improve patient care, there has recently been a growing initiative to conduct RA-related studies in various regions of Saudi Arabia (SA). Nevertheless, data from these investigations have not yet been compiled to highlight the current status of RA management in SA. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to systematically analyze the literature regarding RA in SA to thoroughly examine this topic from various perspectives, including our own personal experiences. Here, we discuss the results of our analysis, which can contribute to the planning of future national guidelines and directives on the care of RA patients in SA. In addition, our findings can promote further research aimed at solving current obstacles in RA management at both the national and international levels.

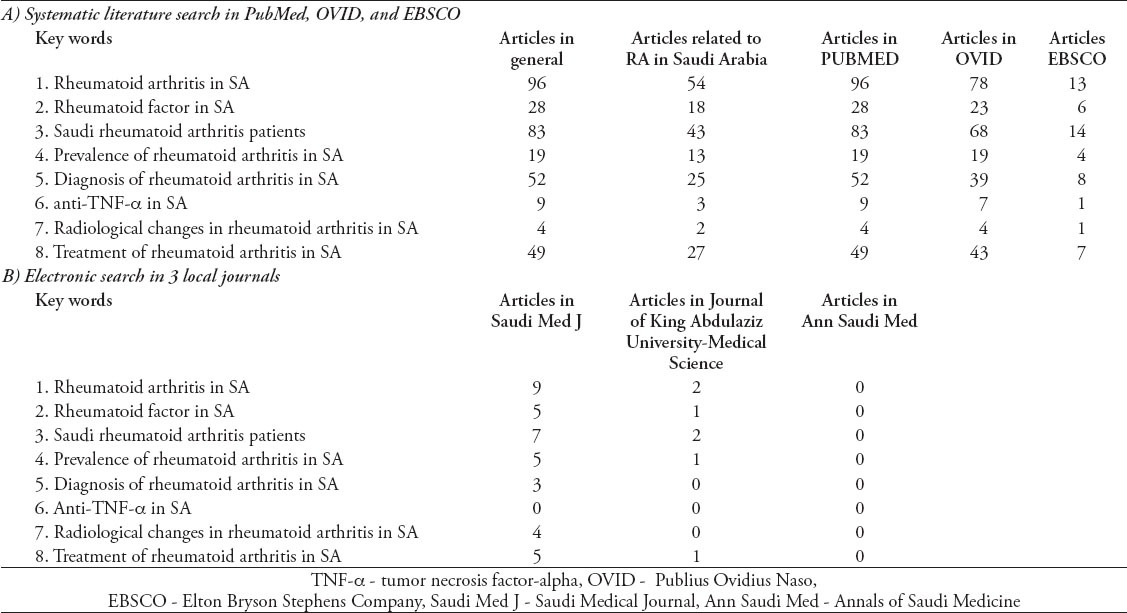

Systematic search strategy and study selection

Here, we have conducted an electronic literature search via MEDLINE using PubMed (US National Library of Medicine, 1984 to February 2014), Ovid, and EBSCO databases. In addition, we performed an electronic search in 3 local journals (for example, Saudi Medical Journal, Annals of Saudi Medicine, and Journal of King Abdulaziz University Medical Science), identifying 2 more articles.5,6 The following search terms were used: “rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia”, “rheumatoid factor in Saudi Arabia”, “diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia”, “Saudi rheumatoid arthritis patients”, and “anti-TNF-a in Saudi Arabia”. Studies on RA in SA were reviewed, and relevant articles were selected (Table 1). Included articles fulfilled the following criteria: 1) prospective study, retrospective study, or review article; and 2) written in English. However, articles on juvenile RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren syndrome, or other rheumatic diseases were excluded. Moreover, studies regarding RA in non-Saudi populations and case reports were excluded. Data were classified according to different categories: epidemiological, clinical features, laboratory, radiological, management, and reviews (Table 2). Eight studies were excluded: 2 represented double publications,7,8 5 were case reports,9-13 and one was conducted on non-Saudi RA patients.14 Ultimately, a total of 43 studies were identified through our literature searches.

Table 1.

Results from a systematic literature search on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Saudi Arabia (SA).

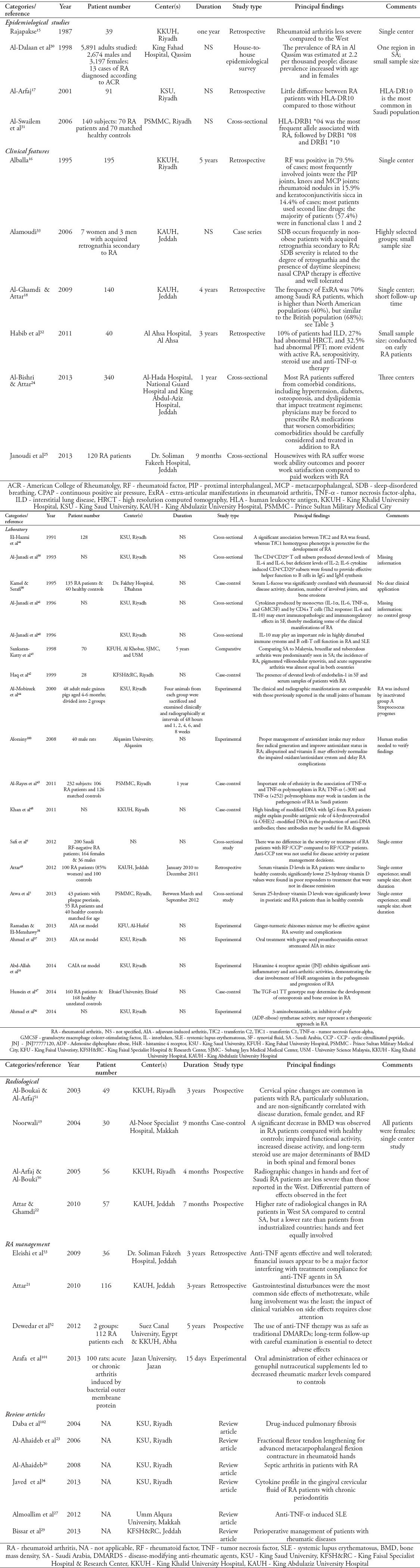

Table 2.

Classification of identified studies on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Saudi Arabia.

Study types and characteristics

We first analyzed the features of the articles identified in our systematic literature search regarding RA in SA (Table 1). We found that most studies involved only a single center.7-15-18 Also, there were a few early articles published by single authors, reporting their own experiences, including retrospective case series following patients over one or 5-year periods at a single center (King Khalid University Hospital).15,16 Subsequently, this pattern of publication continued, with one17,19-21 or multiple authors18,22,23 using a retrospective case methodology to report findings. These publications included both clinical, and laboratory results, which were obtained from cohorts of RA patients from various centers. Additionally, there were some reports published by multiple authors from more than one center using either cross-sectional methodologies24 or questionnaire-based studies.25 We also identified several RA-related review articles published by Saudi authors.26-29

The epidemiology and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia

As previously mentioned, most of the identified studies represented single center experiences. One of the earliest reports indicated that 39 out of 194 RA patients displayed less severe findings when compared to RA patients in “the west”, but no specific details were given.15 In contrast, a later study from the same center, involving 195 patients who were followed over a 5-year period, concluded that the RA disease pattern (rheumatoid factor [RF] positivity) and joint distribution in SA resembled that observed in other developed countries.16 Notably, the only study of its kind, 5,891 adult subjects were analyzed within the Qassim region of SA to determine the prevalence of RA in SA, which was estimated to be 2.2 per thousand people.30 However, future studies are needed to confirm this relatively low rate of RA in SA. Moreover, it was found that RA in SA was more common in women, increasing with age.30

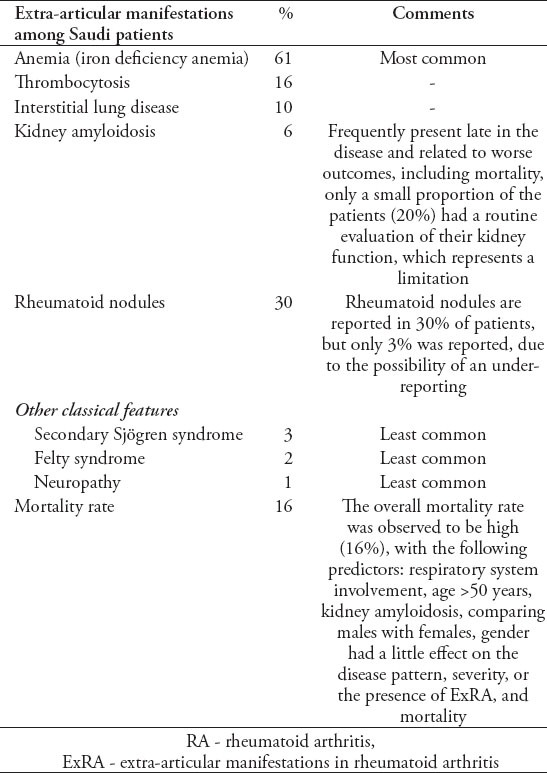

Although human leukocyte antigen (HLA-DR10) was identified as the most common human leukocyte antigen associated with RA in 91 patients from King Saud University,17 those with HLA-DR10 showed only limited differences in clinical presentation when compared to those without.17 However, it must be noted that the study contained no control group. However, a later cross-sectional study among 70 RA patients and 70 controls revealed that HLA-DRB1 *04 was the most frequent allele associated with RA, followed by DRB1 *08, and DRB1 *10.31 In addition, further molecular subtyping revealed a statistically significant association between RA and DRB1 *0405.31 All studies addressing the clinical features of RA in SA are listed in Table 2. Cross-sectional studies24,25 and retrospective case series16,18,32,33 represented the most frequently used methodologies. Among 340 RA patients from 3 different centers in western SA, hypertension (35.9%) was observed to be the most common comorbidity, followed by diabetes mellitus (30.9%), osteoporosis (25.8%), and dyslipidemia (19.4%).24 Furthermore, there was one study involving 140 RA patients at King Abdulaziz University hospital, which retrospectively reviewed the incidence of extra-articular manifestations of RA18 (Table 3). In a highly selected patient group (7 females and 3 males), which acquired retrognathia secondary to RA, 3 patients were found to have obstructive sleep apnea. Additionally, in 40 patients with early RA, 10% were found to have interstitial lung disease, 27% showed abnormal high resolution computed tomography, and 32.5% displayed abnormal pulmonary function tests.32

Table 3.

Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis among Saudi patients.18

Finally, although few studies in the literature have addressed work ability among housewives with RA, a cross-sectional study involving 120 patients from 3 different hospitals in SA found that housewives suffered worse work ability outcomes and poorer work satisfaction compared to paid workers with RA.25

Laboratory-related studies

We identified a total of 18 publications concerning laboratory findings in Saudi RA patients (Table 2). However, one laboratory-related article, which focused on cytokine profiling in gingival crevicular fluid from RA patients with chronic periodontitis, was categorized as a review.34 Among the remaining 17 studies, 4 focused on experimental mouse models,35-38 whereas the majority were retrospective patient studies. These investigations often described the experiences of single centers and represented specific regions of SA.

In addition, the articles on laboratory findings could be classified as either basic science or experimental results. With regard to the basic science papers, we could further divide them into immunological or genetic studies. Among the immunological studies,39-43 the levels of various cytokines were measured in RA patients. However, there was no clear clinical significance for these findings. Most of these articles concluded that cytokines produced by monocytes (interleukin-1 alpha [IL-1 a], IL-6, TNF-a, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GMCSF]) and CD4+ T cells (Th2 cytokines: IL-4 and IL-10) played important immunopathologic and immunoregulatory roles in RA patients.42,44,45 Among the articles that focused on genetics,43,46-48 we identified a case-control study involving 232 Saudi subjects (106 RA patients and 126 matched controls), which was conducted at the Prince Sultan Military Medical City, Riyadh.43 It was found that individuals with the GG genotype at position -308 of TNF-a were susceptible to RA, whereas genotype AA conferred a potentially protective effect with regard to RA susceptibility. In contrast, the GG and AA genotypes of TNF-a at +252 position were suggested to contribute to additive RA susceptibility. Thus, these TNF-a (-308) and TNF-a (+252) polymorphisms may represent pivotal genetic changes that can influence RA susceptibility within the Saudi population. Furthermore, transferrin C (TfC) subtypes were investigated in RA patients, revealing a significant association between TfC2 and RA. Indeed, while the TfC1 homozygous phenotype was found to protect against the onset of RA, TfC2 was linked to an increased risk of cellular damage.46

Finally, 2 additional laboratory studies found that serum levels of vitamin D in RA patients were similar to those of healthy control subjects, whereas lower levels were detected in patients who responded poorly to treatment and were not in disease remission.5,49 Thus, although more research is needed, these laboratory-related findings have yielded important insight into the differences that exist between RA patients.

Radiological studies in rheumatoid arthritis patients

There were 4 articles focusing on the radiological manifestations of RA patients in SA (Table 2), including a 7-month prospective study among 57 RA patients from King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital. This study reported that RA patients from the Western region of SA had a higher rate of radiological changes than those from the Central region, but a lower rate than those from industrialized countries. Notably, the hands and the feet were found to be equally involved. Moreover, no significant associations were observed between radiological findings and RF or smoking history.22 Also, a 4-month study conducted at King Khalid University Hospital revealed similar results with regard to radiographic changes in the hands and feet, demonstrating that Saudi RA patients were less severe than those reported in the West. Moreover, a differential radiological pattern was observed, with lower effects in the feet of RA patients in SA.50 Furthermore, a study conducted at AlNoor Specialist Hospital (Makkah) examined bone mineral density (BMD) in female RA patients, observing a significant decrease in BMD in RA patients compared to healthy controls, which was suggested to stem from impaired functional activity, increased disease activity, and long-term use of steroids.19 Finally, a study assessing radiographic changes in the cervical spine of RA patients concluded that they were common in RA patients, particularly subluxation in the upper cervical spine. However, these changes were somewhat less prevalent than reported, and non-significantly correlated with disease duration, female sex, and RF.51

Studies on rheumatoid arthritis management

We did not identify any randomized controlled trials on the management of RA in SA. Nevertheless, one study that compared 112 RA patients receiving anti-TNF-a therapy to 112 RA patients treated with traditional DMARDs found no significant difference with regard to side effects.52 Moreover, a retrospective study involving 116 RA patients described the presence of methotrexate-related side effects.21 Finally, financial issues were found to be the major factor interfering with compliance related to anti-TNF-a therapy in a study of 36 RA patients at Dr. Soliman Fakeeh Hospital in Jeddah.53

Patient support programs

One national patient support program exists in SA, which was developed and implemented by AbbVie Biopharmaceuticals. The general objective of the program is to improve the quality of care for patients with arthritis, with a particular emphasis on those with RA. It supplies trained ultrasonographers to large rheumatology clinics in SA based on the requests of those clinics. These highly skilled individuals, some of them with medical degrees, provide ultrasonographic findings obtained from RA patients to treating rheumatologists (with the consent of both rheumatologists and patients). In addition, they contribute additional information, including Disease Activity Score in 28 Joints (DAS-28) and Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores. Patient counseling regarding the use of biological agents represents another aspect of the support program that is helpful in busy rheumatology clinics. This support team has participated in various studies on arthritis54 and RA.25

Discussion

This review highlights the current status of RA in SA. There have been great initiatives from various researchers and centers in SA to conduct RA studies. However, our analysis revealed that the majority of findings reported in the literature resulted from descriptive investigations, representing only one or a few centers rather than the national experience. Thus, these studies may not provide an accurate picture of the present state of RA management in SA. We found that biological therapies were introduced early in SA for almost all practicing rheumatologists in both government and private sectors. Moreover, there are no national guidelines on the proper management of RA based on local needs and regulations. In addition, although efforts have been made to establish data registry programs for RA, to date they have not been successful. Nevertheless, improvements in RA care seem imminent, as the number of rheumatologists is increasing in SA. Indeed, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialists has even established a local training program in rheumatology.

Overall, our analysis has revealed that promoting future collaboration between researchers from different centers is essential for increasing the number of patients enrolled in studies and improving the validity of results. In addition, collaborative investigations, which are not limited to one or a few centers, should result in longer follow-up periods and the use of more stringent methodologies. Furthermore, there is a fundamental need to establish a national data registry in SA to unify data from different researchers, which can improve the power and reliability of analyses regarding RA.

Currently, epidemiological results found in the literature regarding RA in SA are suboptimal. In fact, the exact prevalence of RA in the Saudi population remains uncertain. Indeed, the only study to examine the rate of RA in SA was published in 1998, involving a single Saudi region, small sample size, and simple methodology. Therefore, conducting a nation wide study on the prevalence of RA in SA is fundamentally important for developing effective management strategies for disease control.

Over the last decade, several investigations have highlighted the value of ultrasound technology for both clinical and research purposes in rheumatology. Ultrasound is a non-invasive, inexpensive, and non-ionizing radiation imaging technique that provides quick and useful information for the management of RA.4 Access to musculoskeletal ultrasonography (MSKUS) findings by treating rheumatologists within clinics in SA has improved the care of RA patients. Indeed, based on musculoskeletal (MSK) examination alone, it can be difficult to distinguish whether palpable fullness, warmth over a joint, or tenderness on palpation is due to subcutaneous edema, tenosynovitis, paratenonitis [inflamed tissue adjacent to tendons without sheath,55 joint effusion, or synovial proliferation56)]. In this regard, MSKUS was demonstrated to be more sensitive than MSK examination for the detection of joint swelling54,57-60 and better than conventional radiography for identifying erosions.61,62 This increased sensitivity of ultrasound has been shown to result in diagnostic benefit for patients with early synovitis.56,62 Moreover, MSKUS has been employed in the differential diagnosis of early RA.56 In this regard, there are multiple ultrasonographic features that can be used to distinguish different diseases in early inflammatory arthritic disorders. These characteristics have previously been reviewed in detail.56

Since MSKUS is widely used in rheumatology clinics in SA, we believe that it is time to conduct a national study comparing ultrasonographic findings to other outcome measures in RA. In fact, concern has been raised by several studies concerning the validity of the different disease activity measures currently in use. It is true that there is no single gold standard that is applicable for rheumatic disease assessment for all individual patients in clinical trials, clinical research, and clinical care.63 A principal concern is that disease activity measures reflect the sum of several variables rather than a single objective variable, like blood pressure for patients with hypertension or glycated hemoglobin for diabetic patients. Moreover, some of these measures depend on self-reporting by patients, which can be a significant source of bias. Additionally, measures that depend on laboratory values, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), may not necessarily be specific for RA. There is also a major concern regarding the reliability and validity of joint assessment methods, involving the measurement of swollen and tender joint counts by rheumatologists. However, the ability to implement improved outcome measures is limited by practicality, motivation, and resources. Nevertheless, we propose that SA has the capability to incorporate MSKUS findings into busy rheumatology clinics in order to allow for comparative study of these various outcome measures.

Recent treatment recommendations for RA have advocated early introduction of DMARD therapy to preserve joint function, maintain optimal quality of life, and minimize RA-associated comorbid conditions.64,65 In order to achieve these goals a new initiative, called “Treat to Target”,66 was implemented for RA patients in SA. This plan aimed to treat RA patients to the state of remission or low disease activity. However, due to the significant impact of RA on the work ability, it was later recommended that the focus of treatment goals should shift from “Treat to Target” to “Treat to Work”.28 This suggestion resulted from findings obtained form a study examining work ability among RA patients with an emphasis on housewives.25 Thus, it is believed that work ability should also be considered as a valid outcome measure. Therefore, routine use of both MSKUS and work ability as outcome measures in RA could improve the ability to quickly and efficiently achieve treatment targets.

It is known that RA imposes a significant burden on patients, caregivers, employers, and the government.67, 68 In fact, work disability often arises early in the course of the disease. According to several prospective studies, 20-35% of individuals ceased working within 2-3 years of disease onset.69-71 After 5-10 years, the reported work disability rates are approximately 40%.70,72 In this respect, aggressive therapy has been shown to help preserve the work ability of RA patients. In a study of Klimes et al,73 it was reported that patients on biological therapy displayed less reduction in their daily activities (39.8%) compared to patients on DMARDs (50.5%), reflecting approximately 53.6% higher productivity costs related to patients on DMARDs. Moreover, it was recently observed in a cross-sectional study of RA patients in SA that 55% of RA patients suffered from a greater than 50% drop in their work quantity, and 65.8% described a more than 50% effect on their work ability.25 Mau et al74 found that the fastest decline in employment rate among RA patients could be observed within the first 3 years of disease onset, with the 3-year employment rate reduced to 73±5%. Puolakka et al75 supported this finding, concluding that prompt remission translated into the maintenance of work capacity. Taken together, these results reflect the importance of early and aggressive management of RA for preserving work ability.

As outlined in the literature,76 there are several important limitations to identifying promising genetic factors that can predict responses in RA. Indeed, a major challenge in human genetics is to devise a systematic strategy to integrate disease-associated variants with diverse genomic and biological data sets in order to provide insight into disease pathogenesis and/or guide drug discovery for complex traits such as RA.77 Nevertheless, researchers have worked to evaluate approximately 10 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms at the genome-wide level in RA patients, discovering 42 novel RA risk loci, which brings the current total to 101 significant loci.77 These analyses have shed light on fundamental genes, pathways, and cell types that contribute to RA pathogenesis and have provided empirical evidence that the study of genetics in RA patients can provide important information related to drug discovery. In this respect, it is hoped that such genetic studies can also help predict RA predisposition as well as therapeutic responses for patients in SA. So far, laboratory studies have already begun to focus on genetic predisposition to RA43 and the association of RA with specific HLA-DR antigens5 in the Saudi population. As discussed, these findings also have the potential to contribute to the development of specialized drugs for individualized therapy for RA patients in SA.

Regarding the management of RA in SA, recent efforts have been made to identify limitations in RA patient care. In fact, there are reports on the status of MSK examination skills and the education of physicians in SA.54,78,79 Among 296 internal medicine residents in SA, the majority considered themselves incompetent in performing MSK examinations (published in abstract form EULAR 2012).78 Also, MSK procedures currently lack standardization.54,80 In this regard, there has been limited progress in defining and validating simple bedside skills that can aid in the diagnosis of arthritis.54 Furthermore, in general, there have been many international reports addressing the perceived difficulties and inadequate training with regard to performing MSK examination among clinicians and medical students.80-91 Although several factors have been suggested to contribute to poor MSK examination skills,92-96 inadequate training represents an unacceptable explanation considering that physical examination is the most common diagnostic test used by doctors and continues to be an essential tool in modern practice.97 However, despite this body of evidence, there has been very little intervention in SA to address this concern. Thus, dedicated programs for undergraduate and postgraduate education are needed to enhance the competency of rheumatologists. Indeed, improvements in training have the potential to increase the rate of early diagnosis, thereby promoting early treatment of RA. Notably, this simple correlation may not have been previously appreciated among educational leaders in SA.

In addition to programs aimed at enhancing the training of rheumatologists, patient-centered education programs are also essential. In this regard, establishing and implementing initiatives to educate patients about their disease and encourage therapeutic maintenance among patients can complement the improvements made in clinical care within SA. Indeed, these programs are likely to dramatically improve the efficacy of existing drug therapies since recent analysis of the literature has suggested that medication adherence in patients with RA is low, varying from 30-80%.98 In this regard, investigations are needed to specifically assess patient adherence to treatment in SA, including study of the factors contributing to inconsistent treatment as well as analysis of the effect of programs that might promote improved adherence. Indeed, it was already suggested that financial issues represented a major factor interfering with compliance related to anti-TNF-alpha therapy.53 Thus, addressing such issues related to adherence could enhance RA care in SA. For this reason, future discussion and action among rheumatologists regarding patient adherence may be fundamental.

In conclusions, taken together, our thorough analysis of the literature not only highlights the status of current RA management in SA, but also has the potential to contribute to the development of future directives for improving RA care in SA. In this regard, we have identified several topics in RA research that currently require further investigation, including the benefit of ultrasound technology, the genetics of RA, and current RA patient management trends. In addition, evolution of both clinician and patient education programs is fundamental for improving the care of RA patients in SA. Collectively, information obtained from studies on RA in SA can contribute to solving the many obstacles in RA management, at both the national and international levels.

Acknowledgment

This work was supervised and supported by the Alzaidi Chair of Research in Rheumatic Diseases, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Related Articles.

Janoudi N, Almoallim H, Husien W, Noorwali A, Ibrahim A. Work ability and work disability evaluation in Saudi patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Special emphasis on work ability among housewives. Saudi Med J 2013; 34: 1167-1172.

Attar SM. Vitamin D deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis. Prevalence and association with disease activity in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2012; 33: 520-525.

Hanachi N, Charef N, Baghiani A, Khennouf S, Derradji Y, Boumerfeg S, et al. Comparison of xanthine oxidase levels in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other joint inflammations. Saudi Med J 2009; 30: 1422-1425.

References

- 1.Mjaavatten MD, Bykerk VP. Early rheumatoid arthritis: the performance of the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria for diagnosing RA. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:451–466. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padyukov L, Lampa J, Heimbürger M, Ernestam S, Cederholm T, et al. Genetic markers for the efficacy of tumour necrosis factor blocking therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:526–529. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.6.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanmartí R, Ruiz-Esquide V, Hernández MV. Rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical overview of new diagnostic and treatment approaches. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:698–704. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grassi W, Davies A, Boumendil O. Recent Trends and Technology Advances in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical and Ultrasonography and Power Doppler Imaging. European Musculoskeletal Review. 2011;6:148–152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwa MA, Balata MG, Hussein AM, Abdelrahman NI, Elminshawy HH. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis and its association with disease activity and serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:806–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safi M-AA, Houssien DA, Scott DL. Disease Activity and Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (Anti-CCP) Antibody in Saudi RF-Negative Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. JKAU Med Sci. 2012;19:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Arfaj A. HLA-DR pattern of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:92–93. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2001.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Ghamdi A. The Co-Morbidities and Mortality Rate among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients at the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. JKAU Med Sci. 2009;16:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Rikabi AC, Naddaf HO, al Balla SR, al Sohaibani MO. Proteinaceous lymphadenopathy in a patient with known rheumatoid arthritis--case report and review of the literature. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:1087–1089. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Arfaj HF. Klinefelter's syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:86–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakheet SM, Powe J. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease in a patient with thyroid cancer. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Anazi KA, Eltayeb KI, Bakr M, Al-Mohareb FI. Methotrexate-induced acute leukemia: report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Med Case Rep. 2009;2:43–49. doi: 10.4137/ccrep.s3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Shraie NA, Alfadley AA. Lichenoid drug eruption probably associated with rofecoxib. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:795–798. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attar SM, Bunting PS, Smith CD, Karsh J. Comparison of the anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis at an arthritis center. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:446–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajapakse CN. The spectrum of rheumatic diseases in Saudi Arabia. Br J Rheumatol. 1987;26:22–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/26.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alballa SR. The expression of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia. Clin Rheumatol. 1995;14:641–645. doi: 10.1007/BF02207929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Arfaj AS. Characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis relative to HLA-DR in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:595–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Ghamdi A, Attar SM. Extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: a hospital-based study. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:189–193. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noorwali AA. Bone density in rheumatoid arthritis. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:766–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Ahaideb A. Septic arthritis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attar SM. Adverse effects of low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. A hospital-based study. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:909–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attar SM, Al-Ghamdi A. Radiological changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:953–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Ahaideb A, Drosdowech DS, Pichora DR. Fractional flexor tendon lengthening for advanced metacarpophalangeal flexion contracture in rheumatoid hands. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1690–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Bishri J, Attar S, Bassuni N, Al-Nofaiey Y, Qutbuddeen H, Al-Harthi S, et al. Comorbidity profile among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the impact on prescriptions trend. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;6:11–18. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S11481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janoudi N, Almoallim H, Husien W, Noorwali A, Ibrahim A. Work ability and work disability evaluation in Saudi patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Special emphasis on work ability among housewives. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:1167–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan WA, Khan MW. Cancer morbidity in rheumatoid arthritis: role of estrogen metabolites. Biomed Res Int 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/748178. 748178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almoallim H, Al-Ghamdi Y, Almaghrabi H, Alyasi O. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-a Induced Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:315–319. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almoallim H, Kamil A. Rheumatoid arthritis: should we shift the focus from “Treat to Target” to “Treat to Work?”. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:285–287. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bissar L, Almoallim H, Albazli K, Alotaibi M, Alwafi S. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatic diseases. Open Rheumatol J. 2013;7:42–50. doi: 10.2174/1874312901307010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Dalaan A, Al Ballaa S, Bahabri S, Biyari T, Al Sukait M, Mousa M. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18:396–397. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1998.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Swailem R, Al-Rayes H, Sobki S, Arfin M, Tariq M. HLA-DRB1 association in Saudi rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:1019–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Habib HM, Eisa AA, Arafat WR, Marie MA. Pulmonary involvement in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:217–221. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alamoudi OS. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with acquired retrognathia secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR530–CR534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Javed F, Ahmed HB, Mikami T, Almas K, Romanos GE, Al-Hezaimi K. Cytokine profile in the gingival crevicular fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic periodontitis. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abd-Allah AR, Ahmad SF, Alrashidi I, Abdel-Hamied HE, Zoheir KM, Ashour AE, et al. Involvement of histamine 4 receptor in the pathogenesis and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Int Immunol. 2014;26:325–340. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad SF, Attia SM, Zoheir KM, Ashour AE, Bakheet SA. Attenuation of the progression of adjuvant-induced arthritis by 3-aminobenzamide treatment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad SF, Zoheir KM, Abdel-Hamied HE, Ashour AE, Bakheet SA, Attia SM, et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract has potent anti-arthritic effects on collagen-induced arthritis by modifying the T cell balance. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramadan G, El-Menshawy O. Protective effects of ginger-turmeric rhizomes mixture on joint inflammation, atherogenesis, kidney dysfunction and other complications in a rat model of human rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:219–229. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.al-Janadi M, al-Balla S, al-Dalaan A, Raziuddin S. Cytokine production by helper T cell populations from the synovial fluid and blood in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1647–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.al-Janadi M, al-Dalaan A, al-Balla S, al-Humaidi M, Raziuddin S. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) secretion in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis: IL-10-dependent CD4+CD45RO+T cell-B cell antibody synthesis. J Clin Immunol. 1996;16:198–207. doi: 10.1007/BF01541225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.al-Janadi N, al-Dalaan A, al-Balla S, Raziuddin S. CD4+T cell inducible immunoregulatory cytokine response in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:809–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haq A, El-Ramahi K, Al-Dalaan A, Al-Sedairy ST. Serum and synovial fluid concentrations of endothelin-1 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med. 1999;30:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Rayes H, Al-Swailem R, Albelawi M, Arfin M, Al-Asmari A, Tariq M. TNF-α and TNF-β Gene Polymorphism in Saudi Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;4:55–63. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.al-Mobireek AF, Darwazeh AM, Hassanin MB. Experimental induction of rheumatoid arthritis in temporomandibular joint of the guinea pig: a clinical and radiographic study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2000;29:286–290. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sankaran-Kutty M, Das PK, Kannan Kutty M. Synovial biopsy. A comparative study from Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. Int Orthop. 1998;22:189–192. doi: 10.1007/s002640050239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.el-Hazmi MA, al-Ballaa SR, Warsy AS, al-Arfaj H, al-Sughari S, al-Dalaan AN. Transferrin C subtypes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:21–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/30.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussein YM, Mohamed RH, El-Shahawy EE, Alzahrani SS. Interaction between TGF-β1 (869C/T) polymorphism and biochemical risk factor for prediction of disease progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Gene. 2014;536:393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan WA, Moinuddin, Assiri AS. Immunochemical studies on catechol-estrogen modified plasmid: possible role in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:22–29. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Attar SM. Vitamin D deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis. Prevalence and association with disease activity in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Arfaj AS, Al-Boukai AA. Patterns of radiographic changes in hands and feet of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1065–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Boukai AA, Al-Arfaj AS. Rheumatoid arthritis. Radiological changes in the cervical spine. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:396–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dewedar AM, Shalaby MA, Al-Homaid S, Mahfouz AM, Shams OA, Fathy A. Lack of adverse effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α biologics in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: 5 years follow-up. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eleishi HH, Toma NF, Chaki MC, Nada HR. Three years experience with the prescription of anti-TNF-alpha inhibitors at Dr Soliman Fakeeh Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2009;12:14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Almoallim H, Attar S, Jannoudi N, Al-Nakshabandi N, Eldeek B, Fathaddien O, et al. Sensitivity of standardised musculoskeletal examination of the hand and wrist joints in detecting arthritis in comparison to ultrasound findings in patients attending rheumatology clinics. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1309–1317. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Backhaus M, Ohrndorf S, Kellner H, Strunk J, Backhaus TM, Hartung W, et al. Evaluation of a novel 7-joint ultrasound score in daily rheumatologic practice: a pilot project. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1194–1201. doi: 10.1002/art.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thiele RG. Ultrasonography applications in diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38:259–275. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szkudlarek M, Klarlund M, Narvestad E, Court-Payen M, Strandberg C, Jensen KE, et al. Ultrasonography of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints in rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with magnetic resonance imaging, conventional radiography and clinical examination. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R52. doi: 10.1186/ar1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wakefield RJ, Green MJ, Marzo-Ortega H, Conaghan PG, Gibbon WW, McGonagle D, et al. Should oligoarthritis be reclassified? Ultrasound reveals a high prevalence of subclinical disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:382–385. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.007062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vlad V, Berghea F, Libianu S, Balanescu A, Bojinca V, Constantinescu C, et al. Ultrasound in rheumatoid arthritis: volar versus dorsal synovitis evaluation and scoring. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Magni-Manzoni S, Epis O, Ravelli A, Klersy C, Veisconti C, Lanni S, et al. Comparison of clinical versus ultrasound-determined synovitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1497–1504. doi: 10.1002/art.24823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakefield RJ, Gibbon WW, Conaghan PG, O’Connor P, McGonagle D, Pease C, et al. The value of sonography in the detection of bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with conventional radiography. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2762–2770. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2762::AID-ANR16>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Filer A, de Pablo P, Allen G, Nightingale P, Jordan A, Jobanputra P, et al. Utility of ultrasound joint counts in the prediction of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with very early synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:500–507. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sokka T, Rannio T, Khan NA. Disease activity assessment and patient-reported outcomes in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:964–975. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–639. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haraoui B, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, Codreanu C, et al. Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis to Target: multinational recommendations assessment questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1999–2002. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Yelin E. Prevalence and correlates of arthritis-attributable work limitation in the US population among persons ages 18-64: 2002 National Health Interview Survey Data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:355–363. doi: 10.1002/art.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jäntti J, Aho K, Kaarela K, Kautiainen H. Work disability in an inception cohort of patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: a 20 year study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:1138–1141. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Möttönen T, Hannonen P. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis 10 years after the diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1681–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barrett EM, Scott DG, Wiles NJ, Symmons DP. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on employment status in the early years of disease: a UK community-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1403–1409. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eberhardt K, Larsson BM, Nived K, Lindqvist E. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis--development over 15 years and evaluation of predictive factors over time. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klimes J, Dolezal T, Vocelka M, Petrikova A, Kruntoradova K. The effect of biological treatment on work productivity and productivity costs of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Value in Health. 2011;14:A305. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mau W, Bornmann M, Weber H, Weidemann HF, Hecker H, Raspe HH. Prediction of permanent work disability in a follow-up study of early rheumatoid arthritis: results of a tree structured analysis using RECPAM. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:652–659. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.7.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Möttönen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Hakala M, et al. Early suppression of disease activity is essential for maintenance of work capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:36–41. doi: 10.1002/art.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emery P, Dörner T. Optimising treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of potential biological markers of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:2063–2070. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zaini R, Almoallim H, AlRehaily A, Samannodi M, Bawayan M, Hafiz W, et al. [AB1407] Musculoskeletal teaching and training in Saudi Arabia: a national survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(Suppl 3):718. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Almoallim H, Kalantan D, Shabrawishi M, Mandili F, Hafiz H, Samannodi M, et al. Basic Skills in Musculoskeletal Examination: Hands-on Training Workshop. Updated: 2013. Available from: https: //www.mededportal.org/ publication/9398, http://dx.doi.org/10.15766/ mep_2374-8265.9398 .

- 80.Scott DL, Choy EH, Greeves A, Isenberg D, Kassinor D, Rankin E, et al. Standardising joint assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15:579–582. doi: 10.1007/BF02238547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matzkin E, Smith EL, Freccero D, Richardson AB. Adequacy of education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:310–314. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Day CS, Yeh AC, Franko O, Ramirez M, Krupat E. Musculoskeletal medicine: an assessment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med. 2007;82:452–457. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ea860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clawson DK, Jackson DW, Ostergaard DJ. It's past time to reform the musculoskeletal curriculum. Acad Med. 2001;76:709–710. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Clark ML, Hutchison CR, Lockyer JM. Musculoskeletal education: a curriculum evaluation at one university. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:93. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Akesson K, Dreinhöfer KE, Woolf AD. Improved education in musculoskeletal conditions is necessary for all doctors. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:677–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldenberg DL, DeHoratius RJ, Kaplan SR, Mason J, Meenan R, Perlman SG, et al. Rheumatology training at internal medicine and family practice residency programs. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:471–476. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pinney SJ, Regan WD. Educating medical students about musculoskeletal problems. Are community needs reflected in the curricula of Canadian medical schools? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1317–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dequeker J, Esselens G, Westhovens R. Educational issues in rheumatology. The musculoskeletal examination: a neglected skill. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:5–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coady DA, Walker DJ, Kay LJ. Teaching medical students musculoskeletal examination skills: identifying barriers to learning and ways of overcoming them. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:47–51. doi: 10.1080/03009740310004108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Freedman KB, Bernstein J. Educational deficiencies in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:604–608. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200204000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oswald AE, Bell MJ, Snell L, Wiseman J. The current state of musculoskeletal clinical skills teaching for preclerkship medical students. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2419–2426. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges; 2005. Association of American Medical Colleges. Report VII, Contemporary issues in medicine: Muscluskeletal Medicine Education. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Clark ML, Hutchison CR, Lockyer JM. Musculoskeletal education: a curriculum evaluation at one university. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:93. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Riyadh (KSA): Ministry of Health; 2009. Ministry of Health. The Annual Health Report - 1430H-2009. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thompson AE. Improving undergraduate musculoskeletal education: a continuing challenge. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2298–2299. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woolf AD, Akesson K. Primer: history and examination in the assessment of musculoskeletal problems. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:26–33. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Joshua AM, Celermajer DS, Stockler MR. Beauty is in the eye of the examiner: reaching agreement about physical signs and their value. Intern Med J. 2005;35:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van den Bemt BJ, Zwikker HE, van den Ende CH. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:337–351. doi: 10.1586/eci.12.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kamel M, Serafi T. Fucose concentrations in sera from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alorainy M. Effect of allopurinol and vitamin e on rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2008;2:59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Arafa NM, Hamuda HM, Melek ST, Darwish SK. The effectiveness of Echinacea extract or composite glucosamine, chondroitin and methyl sulfonyl methane supplements on acute and chronic rheumatoid arthritis rat model. Toxicol Ind Health. 2013;29:187–201. doi: 10.1177/0748233711428643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Daba MH, El-Tahir KE, Al-Arifi MN, Gubara OA. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:700–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]