Abstract

The insensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to chemotherapy is associated with alternation in tumor cell cycling. This current study was designed to investigate the impact of p15 silencing on the sensitivity of Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells to cisplatin. HepG2/CDDP/1.6 and HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were induced by culture with increased doses of cisplatin and their sensitivities to cis-Diamine dichloroplatinum (CDDP) were determined by 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). The impacts of p15 silencing on the cell cycling and P-gp expression were characterized by flow cytometry, RT-PCR and Western blot assays, respectively Knockdown of p15 expression dramatically reduced the relative levels of p15 expression and the frequency of phase G1, promoting cell cycling. On the other hand, knockdown of p15 expression significantly up-regulated the expression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells, associated with the increased resistance of HepG2 cells to CDDP in vitro.

In conclusion, the p15 may be a critical regulator of the development of CDDP resistance in HepG2 cells.

KEY WORDS: hepatocellular carcinoma, cell cycle, p15, RNA interference, drug resistance

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most malignant tumors worldwide [1], and is generally insensitive to anticancer drugs, which makes chemotherapeutic drug treatment difficult. It is estimated that 70% of patients who have received chemotherapeutic drugs rapidly developed drug resistance [2, 3], which remains a difficult issue. Therefore, discovery of mechanisms underlying the drug resistance is of great significance in the development of new strategies for the intervention of drug-resistant tumors. The development of drug resistance is attributed to the expression of drug-resistance related genes in tumor cells. A previous study has revealed that various cellular pathways may be involved simultaneously in the drug resistance [4]. Increased repair of drug-induced DNA damage, blocked apoptosis, disruptions in the signal pathways, and alterations of factors involved in cell cycling contribute to the development of drug resistance [5, 6]. The cell cycle represents a series of tightly integrated events that allow the cells to grow and proliferate. The cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) are important components of the cell cycle machinery, and are positively regulated by cyclins and negatively regulated by cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs) [7]. p15, one member of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs) family, can prevent transition from the G1 to S phase by inhibiting CDK4/6-cyclinD mediated phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) [8]. Induction of p15 over-expression can induce G1-phase arrest through the TGF-β/Smad pathway [9]. Indeed, down-regulated expression of p15 and related signaling that control G1/S transition are frequently deregulated in human cancers, such as pituitary adenoma, myeloid disease, and gastric cancer [10-12]. Furthermore, loss of p15 expression is associated with the development of lymphoproliferative disorders and tumor formation [13]. Consequently, targeting the cell cycle modulators, CDKI, may be an excellent opportunity for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma [10]. Our previous study has shown that up-regulating p15 expression inhibits the progression of cell cycling and reverses the drug-resistant phenotype in drug-resistant HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells [14]. This study is aimed at examining the impact of p15 knockdown on the progression of cell cycling and resistance to CDDP in CDDP-resistant HepG2 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Establishment of CDDP-resistant HepG2 cells

Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS, Shanghai, China), and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). The cells were exposed to increased doses of cisplatin (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, or 1.6 mg/L, Hospira, Unterach, Australia) for three months to generate a cisplatin-resistant HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cell line. Finally, the cells were maintained in 1.6 mg/L of CDDP in complete medium. In addition, HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells were cultured in the presence of 2.0 mg/L CDDP (designated as HepG2/CDDP/2.0) and were also used for experiments.

MTT assay

The sensitivity of HepG2/CDDP/1.6 and HepG2 cells to CDDP was tested by MTT assays. Briefly, HepG2/CDDP/1.6 and HepG2 cells at 2×105 per well were cultured in 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium in 96-well plates and treated in triplicate with 1.6 or 0 mg/L of CDDP for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. During the last 4h incubation, the cells were exposed to 50 μg/mL of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma, St. Louis, USA). The resulting formaza in individual wells was dissolved with 150 μl of DMSO (Sigma, St Louis, USA) and measured at an absorbance of 570 nm using a VERSAmax spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The cells cultured in medium alone were used as negative controls, and the IC50 for CDDP was calculated using the spass 10.0 software.

Transfection of siRNA

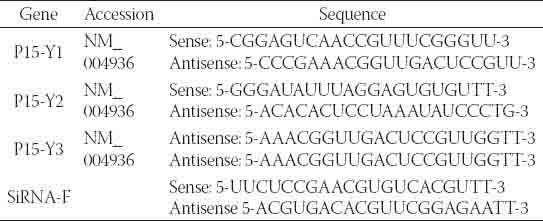

The 21-necleotide p15-specific siRNA Y1, Y2, and Y3 duplexes or control siRNA-F were designed and chemically synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China), and their sequences are shown in Table 1. To knockdown p15 expression, HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells at 5×105 cells/well were incubated overnight in 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium in 6-well plates, and transfected in triplicate with different doses (30-90 nM) of the 21-necleotide p15 specific siRNA Y1, Y2, and Y3 duplexes or control siRNA-F (90 nM), respectively, using Lipofectamine™ 2000, according to the manufacturers’ instruction (Invitrogen). The levels of p15 mRNA transcripts were determined 24, 48, and 72 h later for evaluating the efficacy of p15 silencing by RT-PCR.

TABLE 1.

The sequences of the p15-specific siRNAs

RT-PCR

HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with different doses of Y1, Y2, Y3, or siRNA-F for 24, 48, and 72 h (as described above), and their total RNA was extracted, respectively, using the RNAiso™ Plus reagent, according to the manufacturers’ instruction (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Otsu, Japan). The RNA samples (1 μg/per group) were reversely transcribed into cDNA using the one-step RT-PCR kit (Takara Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative levels of p15 and Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA transcripts were determined by PCR using the cDNA as the template and specific primers. The sequences of primers were sense 5-CGTTAAGTTTACGGCCAACG-3 and anti-sense 5-GGTGAGAGTGGCAGGGTCT-3 for p15 (302bP), and sense 5-GAGCCAAAAGGTCAT- CATCTC-3 and anti-sense 5-AAAGGTGGAGTGGGT- GTC-3 for GAPDH (542bp), respectively. The PCR reactions were performed in duplicate at 94°C for 5 min and then subjected to 30 cycles of 95a°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by an extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were resolved on agarosegel electrophoresis, and the relative levels of p15 mRNA transcript to GAPDH were determined using the Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Beijing, China).

Cell cycle analysis

HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected in triplicate with the Y3 or control siRNA-F (90 nM) for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, and the cells were harvested, respectively. Subsequently, the cells (1 × 106 cells/tube) were washed with pre-cooled phosphate buffered solution (PBS) twice and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol, followed by staining with 20 μg/mL of propidium iodide (PI, Sigma). The distribution of individual cell cycle phases was analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for analysis of the DNA contents.

Western blot analysis

HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with Y3 (90 nM) or siRNA-F for 72 h and the cells were harvested, respectively. The cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer for Western blot (Beyo-time Institute Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 30 min on ice, and their protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA reagents (Pierce, Rockford, USA), according to the manufacturers’ instruction. The cell lysates were mixed with SDS-PAGE Sample Loading Buffer (5×) and boiled for 10 min, followed by centrifuging. The cell lysates (50μg/lane) were separated by electrophoresis on 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred into PVDF membranes. Subsequently, the membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST with 0.1% Tween 20 for 2 h at room temperature, and then incubated overnight with 2 μg/ml of mouse-anti-human p15 monoclonal antibody and 1:200 diluted mouse-anti-human p-gp polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, USA) at 4°C. After washing, the bound antibodies were detected with 1:20000 diluted peroxidase-conjugated affinity-chromatography pure goat anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, and visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Gel Doc™ XR+ Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The relative levels of p15 proteins to control GAPDH were analyzed using Image Lab™ 2.0 Software (MCM DESIGN, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD of each group. The difference among groups was analyzed by one way of analysis variance (ANOVA), and the difference between groups was determined by Student’s t-test using Excel 7.0 software. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Establishment of CDDP-resistantHepG2/CDDP/1.6

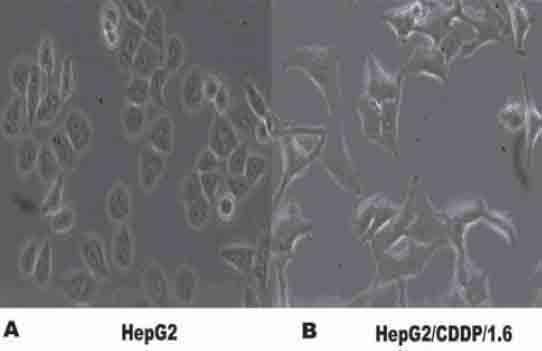

To determine the impact of modulating p15 expression on the chemo-resistance of HepG2 cells to CDDP, HepG2 cells were cultured with increased doses of CDDP for three months and maintained with 1.6 mg/L of CDDP to generate the CDDP-resistant HepG2/CDDP/1.6. Analysis of its sensitivity, together with its parent HepG2 cells, to cisplatin revealed that the IC50 values of HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells to cisplatin was 3.47 ± 0.06 mg/L, and their parent HepG2 cells was 0.51 mg/L ± 0.01 mg/L, resulting in a resistance index of 6.8. HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells grow slowly in vitro to accommodate the context of cisplatin (Figure 1). Hence, the establishment of CDDP-resistant HepG2/CDDp/1.6 cells provides an excellent model for the following studies.

FIGURE 1.

The morphology of CDDP-resistant HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were cultured in the presence of increased concentrations of CDDP for three months and became a CDDP-resistant cell line, HepG2/CDDP/1.6. (A): HepG2; (B): HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells (200× magnification).

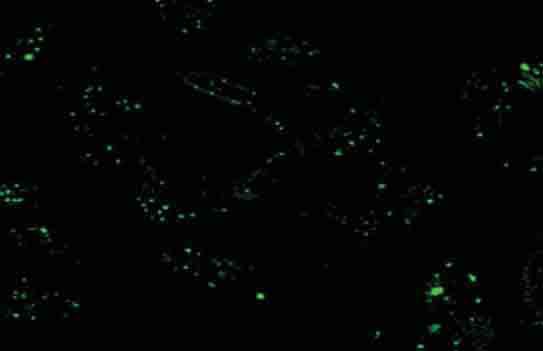

Knockdown of p15 expression in the CDDP-resistant HepG2 cells

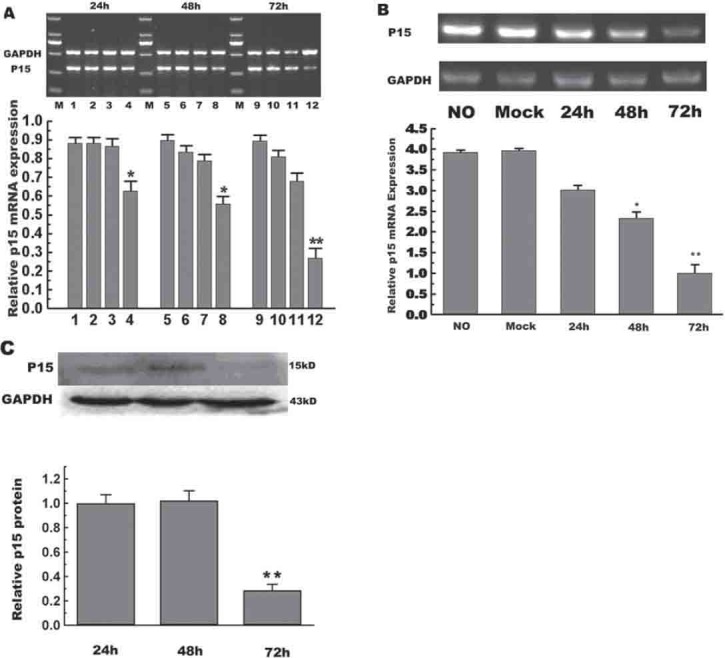

To optimize the conditions, HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells were transfected with 30-90 nM of control siRNA-F for 24 h. As shown in Figure 2, transfection with 90 nM of siRNA-F for 24 h resulted in nearly 95% of cells carrying the siRNA-F. Next, we determined the efficacy of transfection with the p15-specific siRNA on the p15 expression in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were cultured overnight with compete medium in the presence of 2.0 mg/L of CDDP, and transfected with 30-90 nM of control siRNA-F or the p15-specific siRNA Y1, Y2, or Y3 for 24-72 h, respectively. As shown in Figure 3 A and 3B, while transfection with the siRNA-Y1 did not change the levels of p15 mRNA transcripts, transfection with the siRNA-Y2 obviously reduced the levels of p15 mRNA transcript by 30% in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. More importantly, transfection with the siRNA-Y3 significantly reduced the levels of p15 mRNA transcripts even at 24 h post transfection, and transfection with the siRNA-Y3 for 72 h dramatically minimized the p15 expression by 70%. Similarly, transfection with the siRNA-Y3 inhibited the expression of p15 proteins in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells in vitro (Figure 3 C). Hence, the siRNA-Y3 inhibited the expression of p15 in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells in a dose and time-dependent manner.

FIGURE 2.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) analysis of transfected HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with control siRNA-F (90 nM) for 24h and subjected to LSCM analysis. The green dots represent the transfected siRNA (400× magnification).

FIGURE 3.

Transfection with p15-specific siRNA inhibits the expression of p15 in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with different p15-specific siRNAs (Y1, Y2, and Y3) or control siRNA-F at a final concentration of 90 nM for the indicated periods. The relative levels of p15 mRNA expression to control GAPDH were determined by RT-PCR and Western blot assays. (A) RT-PCR analysis of p15 mRNA transcripts. 1, 5, and 9: Transfected with siRNA-F; 2, 6, and 10: Transfected with siRNA Y1; 3, 7, and 11: Transfected with siRNA Y2; 4, 8, and 12: Transfected with siRNA Y3. (B) RT-PCR analysis. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with 90 nM of siRNA-F (mock) for 72 h or with siRNA Y3 for the indicated periods. (C) Western blot analysis: The relative levels of p15 protein were determined by Western blot assays. Data are expressed as representative images and mean ± SD of individual groups from three separate experiments.

Knockdown of p15 expression promotes cell cycle progression in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells

To determine the impact of p15 silencing on the progression of cell cycling, HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with 90 nM of control siRNA-F or siRNA-Y3 for 24-72 h, respectively. The cells were harvested and their cell cycling was characterized by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 4). The frequency of HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells that had been transfected with control siRNA-F at G1 phase increased gradually with the extended culture time. In contrast, transfection with the siRNA-Y3 appeared to promote the progression of cell cycling in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. Evidentially, the frequency of siRN-Y3-transfected HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells at G1 phase was reduced to 53.8% at 24 h post transfection and further decreased to 48.8% at 72 h post transfection (p<0.05). Therefore, knockdown of p15 expression promoted the progression of cell cycling in HepG2/CDDP-2.0 cells in vitro.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of cell cycle. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with 90 nM of control siRNA-F (A) or siRNA Y3 (B) for the indicated periods and the distribution of different phases of cell cycling was characterized by flow cytometry.

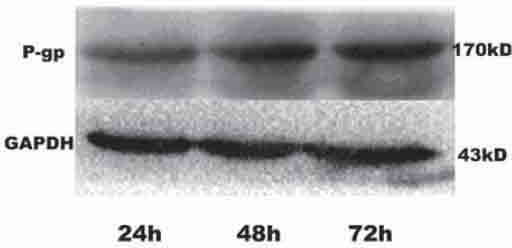

Effect of p15 silencing on the expression of p-gp in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells

The increased levels of p-gp expression are associated with drug resistance in tumor cells [15, 16]. Finally, we examined the impact of p15 silencing on the expression of p-gp in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with 90 nM of siRNA-Y3 for 24-72 h, respectively, and the relative levels of p-gp proteins were determined by Western blot assays (Figure 5). Apparently, the levels of p-gp expression increased with extended culture time in the Y3-transfected HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells, which may be associated with increased drug-resistance to CDDP in HepG2 cells.

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of p-gp expression. HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells were transfected with 90 nM of siRNA Y3 for varying periods, and the relative levels of p-gp expression to control GAPDH were determined by Western blot assays. Data shown are representative images from three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The change in cell cycling is associated with drug resistance in tumor cells [17]. Notably, CDKIs can inhibit the progression of cell cycling and rescue drug resistance in some tumors. In this study, we examined the effect of p15 silencing on the cell cycling and CDDP-resistance in HepG2 cells. We first generated the CDDP-resistant HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells in vitro by continually culturing HepG2 cells with increased concentrations of CDDP. We found that HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells grow slowly in vitro to accommodate the context of cisplatin. Furthermore, we transfected HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells with individual siRNA specific targeting p15 and found that transfection with the Y3 siRNA inhibited the p15 expression in a dose and time-dependent manner in vitro. More importantly, while transfection with control siRNA did not alter the progression of cell cycling with increased frequency of HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells at phase G1, knockdown of p15 significantly reduced the frequency of HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells at phase G1, demonstrating that knockdown of p15 promoted the progression of cell cycling in CDDP-resistant HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells in vitro. Finally, we found that knockdown of p15 up-regulated the expression of P-gp in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells in vitro. These data extend our previous findings that up-regulating p15 expression reverses the drug resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [14]. Given that promotion of cell cycling is associated with drug resistance in tumor cells, our findings suggest that p15 may be a critical regulator of the development of drug resistance in HepG2 cells. The drug-resistant tumor cells usually maintain low concentrations of anti-tumor drug in the cell body, which is associated with an increase in the expression of transporter protein P-gp [18]. The CDDP-resistant tumor cells are insensitive to cisplatin, which can bind to DNA, create adducts and break DNA strand, leading to inhibition of DNA replication. The CDDP-resistant tumor cells usually have sufficient capacity to repair damaged DNA and maintain cell cycling [19]. The cellular response to DNA damage can activate cell cycle checkpoints that serve as natural surveillance mechanisms for DNA integrity. Indeed, the CDDP-resistant HepG2 cells usually exhibit cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase, a survival mechanism, which provides an excellent opportunity for the tumor cells to repair damaged DNA [7]. We found that the frequency of HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells in G0/1 phage increased gradually with the increased time in the presence of cisplatin, while the distribution of different phases of cell cycle did not change significantly in stably CDDP-resistant HepG2/CDDP/1.6 cells. The consistent resistance may stem from decreased uptake of cisplatin and/or increased DNA repair [19]. Our data are consistent with a previous observation of cell cycle arrest at phase G0/G1 of human QGY/CDDP cells [20]. Our previous study has demonstrated that up-regulation of p15 expression induces cell cycle arrest at G1 phase and inhibits the cell proliferative activity, reducing drug-resistance in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells [14]. In the current study, we found that knockdown of p15 expression promoted cell cycling and increased CDDP-resistance in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. Together, p15 is a negative regulator of cell cycle, associated with the development of CDDP-resistance in HepG2 cells [10, 21]. RNA interference (RNAi) is a powerful technique to silence gene expression post-transcriptionally, and it can inhibit the mRNA translation and promote mRNA degradation [22]. The RNAi technique has been a promising therapeutic strategy [23]. Chemically synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA) is currently being evaluated as a potentially useful method for developing highly specific gene-silencing therapeutic reagents [22]. We found that transfection with the Y3 p15-specific siRNA effectively silenced p15 expression, but up-regulated the p-gp expression in the HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. Apparently, treatment with the p15-specific siRNA might not increase the sensitivity of cells to CDDP, suggesting that combination with other strategies, such as CDKI or other chemotherapeutic reagents targeting multiple points of cell cycle, may be more effective in rescuing the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy. In summary, our data indicated that knockdown of p15 expression by siRNA promoted cell cycling and increased CDDP-resistance, which was associated with up-regulated expression of P-gp in HepG2/CDDP/2.0 cells. Therefore, our findings demonstrated that p15 is a negative regulator of cell cycling, associated with the development of CDDP-resistance in HepG2 cells. Conceivably, p15 may serve as a therapeutic target in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This program has been supported by Natural Science Foundation Project of CQ CSTC. (Number: CSTC, 2010BA5011). We thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- [1].Di Bisceglie AM. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(9):S169–171. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shi LX, Ma R, Lu R, Xu Q, Zhu ZF, Wang L, et al. Reversal effect of tyroservatide (YSV) tripeptide on multidrug resistance in resistant human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line BEL-7402/5-FU. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(1):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jacqueline Whang-Peng, Ann-Lii Cheng, Chiun Hsu, Chien-Ming Chen. Clinical Development and Future Direction for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Exp Clin Med. 2010;2(3):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fojo T. Multiple paths to a drug resistance phenotype: Mutations, translocations, deletions and amplification of coding genes or promoter regions, epigenetic changes and microRNAs. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10(1-2):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shah MA, Schwartz GK. Cyclin dependent kinases as targets for cancer therapy. Update on cancer therapeutics. 2006;1(3):311–332. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shah MA, Schwartz GK. Cell Cycle-mediated Drug Resistance: An Emerging Concept in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2168–2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. The cell cycle: a review of regulation, deregulation and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif. 2003;36:131–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jeffrey PD, Tong L, Pavletich NP. Structural basis of inhibition of CDK-cyclin complexes by INK4 inhibitors. Genes Dev. 2000;14(24):3115–3125. doi: 10.1101/gad.851100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Matsuura I, Denissova NG, Wang G, He D, Long J, Liu F. Cyclin dependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature. 2004;430(6996):226–31. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sakellariou S, Liakakos T, Ghiconti I, Hadjikokolis S, Nakopoulou L, Pavlakis K. Immunohistochemical expression of P15 (INK4B) and SMAD4 in advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(2A):1079–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rosu-Myles M, Wolff L. p15Ink4b: Dual function in myelopoiesis and inactivation in myeloid disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;40(3):406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Musat M, Morris DG, Korbonits M, Grossman AB. Cyclins and their related proteins in pituitary tumourigenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;326(1-2):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Latres E, Malumbres M, Sotillo R, Martin J, Ortega S, Martin-Ca-ballero J, et al. Limited overlapping roles of P15MK4b and P18MK4c cell cycle inhibitors in proliferation and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2000;19(13):3496–3506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang W, Chen WQ. MDR-reversing effect of P15 to multidrug-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Fourth Mil Med Univ. 2009;30(15):1383–1386. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gan SY, Zhong XY, Xie SM, Li SM, Peng H, Luo F. Expression and significance of tumor drug resistance related proteins and betacatenin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(3):323–329. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Warmann S, Hunger M, Teichmann B, Flemming P, Gratz KF, Fuchs J. The Role of the MDR1 Gene in the Development of Multidrug Resistance in Human Hepatoblastoma: clinical course and in vivo model. Cancer. 2002;95(8):1795–1801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Manish A. Shah, Gary K. Schwartz. Cell Cycle-mediated Drug Resistance: An Emerging Concept in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2168–2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Endicott JA, Ling V. The Biochemistry of P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:137–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boulikas T. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin and its liposomally encapsulated form, Lipoplatin™ Lipoplatin™ as a chemotherapy and antiangiogenesis drug. Cancer Therapy. 2007;5:351–376. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yang JX, Tang WX. Establishment of a cisplatin-induced human hepatocellular carcinoma drug-resistant cell line and its biological characteristics. Ai Zheng. 2002;21:8, 872–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu TG, Yin JQ, Shang BY, Min Z, He HW, Jiang JM, et al. Silencing of hdm2 oncogene by siRNA inhibits p53-dependent human breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11(11):748–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Izquierdo M. Short interfering RNAs as a tool for cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12(3):217–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Novina CD, Sharp PA. The RNAi revolution. Nature. 2004;430:161–164. doi: 10.1038/430161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]