Abstract

5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors (5-HT2A-Rs) are G-protein coupled receptors. In agreement with their location in the brain, they have been implicated not only in various central physiological functions including memory, sleep, nociception, eating and reward behaviors, but also in many neuropsychiatric disorders. Interestingly, a bidirectional link between depression and epilepsy is suspected since patients with depression and especially suicide attempters have an increased seizure risk, while a significant percentage of epileptic patients suffer from depression. Such epidemiological data led us to hypothesize that both pathologies may share common anatomical and neurobiological alteration of the 5-HT2A signaling. After a brief presentation of the pharmacological properties of the 5-HT2A-Rs, this review illustrates how these receptors may directly or indirectly control neuronal excitability in most networks involved in depression and epilepsy through interactions with the monoaminergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmissions. It also synthetizes the preclinical and clinical evidence demonstrating the role of these receptors in antidepressant and antiepileptic responses.

Keywords: 5-HT, 5-HT2A receptor, antidepressants, antipsychotics, depression, epilepsy

The 5-HT2A-Rs: Distribution in Brain Areas Releted to Depression and Epilepsy and their Pharmacological Properties

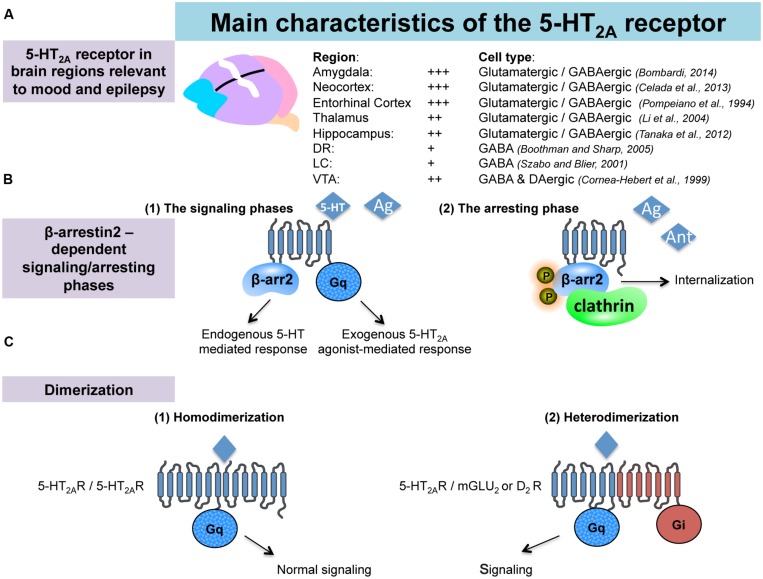

Serotonin is an important modulator of a plethora of physiological functions in the brain. The diverse 5-HT effects are mediated by seven classes of 5-HT receptors (5-HT-Rs) and, at least, 15 subtypes (Barnes and Sharp, 1999). Pharmacological and genetic studies have highlighted an important role for 5-HT2A-Rs in specific CNS pathologies including depression and epilepsy. 5-HT2A-Rs are members of the metabotropic seven transmembrane-spanning receptors superfamily frequently referred to as GPCRs. In particular, 5-HT2A-Rs belong to the 5-HT2 subfamily consisting, with 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C, of three Gq/G11-coupled receptors, which mediate excitatory neurotransmission (Millan et al., 2008). Using in situ hybridization, western blot and immunohistochemical analyses in rodents, 5-HT2A-R mRNA or the protein have been identified in various brain regions involved in emotionality and epilepsy, such as the amygdala, the hippocampus (Bombardi, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2012), the thalamus (Li et al., 2004) as well as in several cortical areas (entorhinal, cingulate, piriform, and frontal cortices Pompeiano et al., 1994; Santana et al., 2004; Amargos-Bosch et al., 2005; de Almeida and Mengod, 2007; Figure 1A). 5-HT2A-Rs have also been detected in all monoaminergic brainstem levels; i.e., the MRN/DRN, the LC and the VTA (Cornea-Hebert et al., 1999; Doherty and Pickel, 2000; Nocjar et al., 2002; Quesseveur et al., 2012; Figure 1A), which also strongly suggests their indirect role in mood and depression by regulating the monoaminergic systems. Indeed, 5-HT2A-Rs act at the monoaminergic somatodendritic or nerve terminals levels either through a direct or indirect action involving glutamatergic and/or GABAergic neurons (Di Giovanni, 2013).

FIGURE 1.

Anatomical and pharmacological properties of the 5-HT2A receptors in the brain. (A) 5-HT2A receptors (5-HT2A-Rs) are located in brain regions involved in emotionality and epilepsy. (B) Interactions between 5-HT2A-Rs and beta-arrestin 2. According to the nature of the 5-HT2A-Rs agonist (endogenous/exogenous), 5-HT2A-Rs-mediated signaling may recruit beta-arrestin2-dependant or -independent pathways (signaling phases). Such a beta-arrestin2 is also involved in the down regulation/internalization of the 5-HT2A-Rs (arresting phase). (C) Dimerization of the 5-HT2A-Rs with GPCRs is necessary to activate signaling pathway.

A major feature of the 5-HT2A-Rs lies in their interactions with β-arrestin. Previous work showed that the 5-HT2A-Rs colocalize with β-arrestin-1 and -2 in cortical neurons (Gelber et al., 1999). Interestingly, it has been shown in β-arrestin-2 KO mice (β-Arr2-/-), in which 5-HT2A-Rs were predominantly localized to the cell surface, that 5-HT was no longer capable of inducing behavioral responses (i.e., head-twitch). These observations suggested that β-arrestin-2 mediates intracellular trafficking of the 5-HT2A-Rs (Figure 1B), and that the cellular events play a role in the induction of head-twitch in response to elevated 5-HT levels. Alternatively, the authors found that the preferential 5-HT2A-R agonist DOI still produces the head-twitch in β-Arr2-/- mice thereby suggesting that β-arrestins are not required for DOI-mediated response (Abbas and Roth, 2008; Schmid et al., 2008). These data emphasize the contribution of the nature of the ligand in determining the receptor signaling pathway and, ultimately, the physiological responses induced by the compound. 5-HT2ARs coupling to the intracellular scaffolding proteins β-arrestins can either dampen or facilitate GPCRs signaling, and therefore, represent a key point at which receptor signaling may diverge in response to particular ligands (Figure 1B).

There is another mechanism by which the 5-HT2-Rs subtypes can regulate their signaling. Recent evidence demonstrates that these receptors can form stable homo- (Herrick-Davis et al., 2005; Brea et al., 2009) and heteromeric complexes with other types of GPCRs including the mGluR2 and D2-DA Rs (González-Maeso et al., 2008; Albizu et al., 2011; Fribourg et al., 2011; Lukasiewicz et al., 2011; Moreno et al., 2011; Delille et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2012; Figure 1C). The in vivo functional consequences of such oligo-dimerization of 5-HT2A-Rs has yet to be determined but this process is likely responsible for changes in binding and coupling properties of the receptors. Supporting this hypothesis, it has been reported that head-twitch induced by the preferential 5-HT2A-R agonists lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and DOI is completely abolished in mGlu2 knock-out (mGlu2-/- KO) mice (González-Maeso et al., 2007; Moreno et al., 2011, 2012; González-Maeso, 2014).

Both examples illustrate the fact that the functional activity of the 5-HT2A-Rs is finely regulated, notably through its interactions with β-arrestin-2 or other GCPRs at the cell membrane. A better knowledge of the physiological relevance of such interactions may help identify new strategies to modulate 5-HT2A-Rs-mediated transmission.

The 5-HT2A-Rs in the Modulation of Neurotransmission

GABA/Glutamate

Serotonergic neurotransmission and more particularly activation of post-synaptic 5-HT2A-Rs in the PFC play a pivotal role in the regulation of the neuronal activity of this brain region. As mentioned in the first part of this review, a substantial proportion of excitatory pyramidal neurons express the 5-HT2A-R mRNA (Santana et al., 2004; Amargos-Bosch et al., 2005; de Almeida and Mengod, 2007), while these mRNAs are also present in ~25% of GAD-containing cells (Santana et al., 2004). Functional in vitro studies showed that 5-HT increased glutamatergic spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents (EPSCs) in pyramidal neurons in layer V of the PFC and this effect was mediated by 5-HT2A-Rs (Aghajanian and Marek, 1999; Celada et al., 2013). Interestingly, intracellular recordings from pyramidal neurons in layers V and VI of the rat mPFC indicated that the application of the 5-HT2A/2C-R agonist DOB produced a biphasic modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced responses, e.g., membrane depolarization, bursts of action potentials and inward current (Arvanov et al., 1999). Indeed, DOB facilitated and inhibited NMDA responses at low and higher concentrations, respectively while these effects were blocked by the 5-HT2A-R antagonist MDL100907 (Aghajanian and Marek, 1997; Arvanov et al., 1999). These results confirmed a previous report showing that iontophoretic application of DOI at low and high ejecting currents facilitated and inhibited, respectively, glutamate-evoked firing rates of pyramidal cells in the mPFC (Ashby et al., 1990) thereby demonstrating the complex regulation of these cells by 5-HT2A-Rs. In vivo, the systemic administration of DOI has been shown to affect the firing rate of pyramidal neurons, since it produced both cell excitation and inhibition (Puig et al., 2003). It is possible that the inhibition of pyramidal neurons by DOI concerns a sub-population of cells innervated by 5-HT2A-Rs-expressing GABAergic interneurons. Consistent with this hypothesis, the intra-cortical injection of DOI dose-dependently increased local extracellular GABA levels in rats while systemic DOI administration resulted in Fos protein expression in GAD67-immunoreactive interneurons of the PFC (Abi-Saab et al., 1999). It has also been demonstrated that the local application of DOI in the mPFC increased 5-HT release (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001; Bortolozzi et al., 2003; Amargos-Bosch et al., 2004). Such elevation in cortical 5-HT outflow produced local glutamate release (Mocci et al., 2014) and subsequent activation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/NMDA receptor located on the 5-HT nerve terminals. In agreement with this hypothesis the DOI-induced increase in cortical 5-HT outflow was reversed by NBQX (an AMPA-KA antagonist) but not by MK-801 (a NMDA antagonist; Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001). Altogether, these findings indicate that 5-HT and glutamate positively interact in the PFC and both have a tendency to become self-reinforcing.

If the activation of the 5-HT2A-Rs mainly stimulates the activity of excitatory pyramidal neurons, an interaction with inhibitory GABAergic neurons is also possible not only in the PFC but also in other serotonergic nerve terminal regions regulating mood-related behavior.

rs. For example, in the PAG area, the stimulation of 5-HT2A-Rs was shown to cause a panicolytic-like effect that is mediated by facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission (de Oliveira Sergio et al., 2011). In the amygdala, double immunofluorescence labeling demonstrated that the 5-HT2A-Rs are primarily localized to parvalbumin-containing interneurons suggesting that 5-HT primarily acts via 5-HT2A-R to facilitate BLA GABAergic inhibition (Jiang et al., 2009). Accordingly, alpha-methyl-5-HT, a 5-HT2-Rs agonist, enhanced frequency and amplitude of spontaneous inhibitory post-synaptic currents (sIPSCs) recorded on the BLA neurons in vitro, and this effect was blocked by selective 5-HT2A-R antagonists (Jiang et al., 2009). In the hippocampus, the activation of 5-HT2A-Rs has also been proposed to increase GABAergic synaptic activity in the CA1 region (Shen and Andrade, 1998).

Monoamines

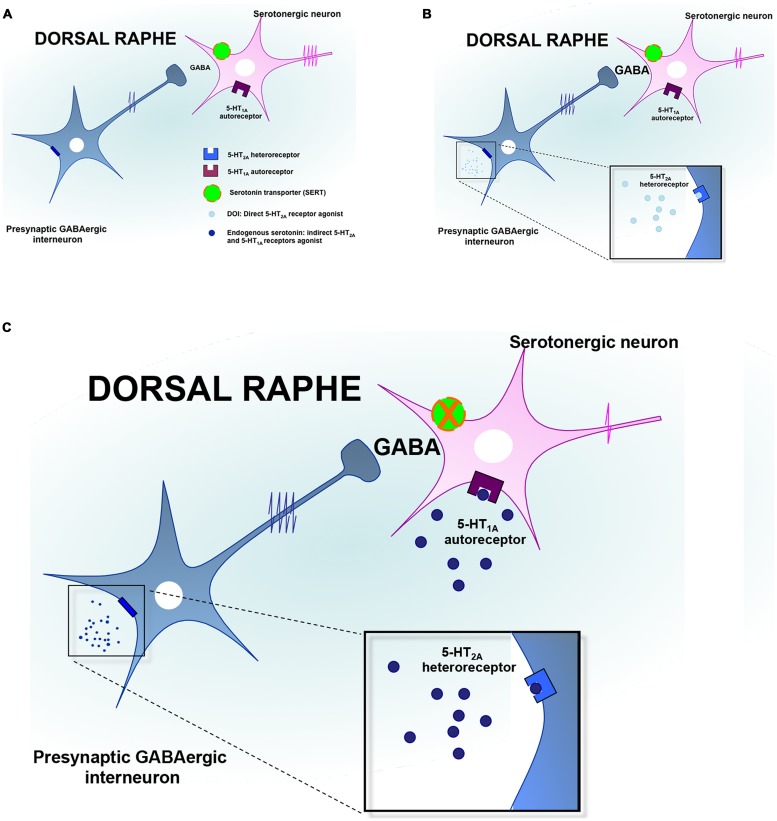

As mentioned earlier, immunoreactivity for the 5-HT2A-Rs has been identified in the DRN and more particularly on GABAergic interneurons (Xie et al., 2002; Serrats et al., 2005). It should be noted that serotonergic raphe nuclei receive a prominent GABAergic input via distant sources as well as interneurons (Harandi et al., 1987; Bagdy et al., 2000; Gervasoni et al., 2000; Varga et al., 2001; Vinkers et al., 2010), and functional evidence suggests that the activation of GABA release in the DRN may be under the control of the 5-HT2A-Rs (Figure 2). Indeed, it has been reported that the activation of these receptors increased Fos expression in GAD-positive DRN neurons (Boothman and Sharp, 2005; Quérée et al., 2009). Accordingly, in vitro studies demonstrated that the local application of DOI in this brain region induces a dose-dependent increase in the frequency of inhibitory post-synaptic currents (IPSCs; Liu et al., 2000; Gocho et al., 2013). In vivo recordings in the DRN showed that the systemic administration of DOI attenuated the firing rate of 5-HT neurons (Wright et al., 1990; Garratt et al., 1991; Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001; Boothman et al., 2003; Bortolozzi et al., 2003; Boothman and Sharp, 2005; Quesseveur et al., 2013). In a recent study, we extended these observations to the fact that the 5-HT2A-Rs also played an important role in the acute electrophysiological response to SSRIs. Indeed, since it has long been recognized that the inhibitory effect of SSRI on 5-HT firing rate was mediated by the overactivation of somatodendritic 5-HT1A autoreceptor in the DRN (Gardier et al., 1996), we blocked this mechanism by using the 5-HT1A-R antagonist WAY100635 (Quesseveur et al., 2013). In these conditions, the inhibitory effects of SSRI escitalopram on DRN 5-HT neuronal activity remained intact while this residual response was reversed by MDL100907, a potent and selective 5-HT2A-Rs antagonist. Together, these findings emphasize the fact that the pharmacologic inactivation of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor is necessary but likely not sufficient to fully prevent the acute inhibitory effects of SSRI on DRN 5-HT neuronal activity. The concomitant blockade of the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A-Rs is therefore required to prevent the undesired negative effects of SSRI on the serotonergic system (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Regulation of serotonin neuronal activity by the 5-HT2A receptors in the dorsal raphe. (A) The dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) contains GABAergic interneurons expressing the 5-HT2A receptors (5-HT2A-Rs) and which project on serotonergic neurons cell bodies to regulate their firing activity. (B) In response to the activation of 5-HT2A-Rs by preferential agonists such as DOI, the neuronal activity of GABAergic interneurons is increased leading to an accumulation of GABA in the synaptic cleft. Such an elevation of GABAergic tone contributes to inhibit DRN 5-HT neurons discharge. (C) In response to the administration of SSRIs, endogenous serotonin activates the 5-HT1A autoreceptors and the 5-HT2A heteroreceptors thereby producing additional inhibitory influences onto DRN 5-HT neurons to silence their activity.

There are alternative mechanisms by which the activation of the 5-HT2A-Rs might reduce the firing rate of DRN 5-HT neuronal activity. For example, it has been proposed that such an inhibitory action may also result from the activation of the 5-HT2A-Rs located on GABA interneurons in the LC (Szabo and Blier, 2001, 2002). In keeping with these data, evidence also suggested that the sustained administration of SSRI produced similar electrophysiological effects while antipsychotics displaying 5-HT2A-R antagonistic activity such as risperidone, reversed this attenuation in noradrenergic neuronal activity (Pandey et al., 2002; Dremencov et al., 2007). In light of the prominent excitatory NE innervation of the DRN (Baraban and Aghajanian, 1980; Vandermaelen and Aghajanian, 1983; Mongeau et al., 1997), the impairment of DRN 5-HT neuronal activity induced by DOI could be secondary to its inhibitory effect on LC NE neurons. In support of this latter hypothesis, we recently demonstrated in mice that the lesion of noradrenergic neurons with the neurotoxin DSP4 significantly attenuated DOI-induced decrease in DRN 5-HT neuronal activity (Quesseveur et al., 2013). Finally, it is important to note that 5-HT2A-Rs located in the PFC may also play a prominent role in the regulation of the DRN notably given the reciprocal anatomical and functional interactions between both regions. However, as mentioned above, evidence suggested that activation of cortical 5-HT2A-Rs increased the firing rate of DRN 5-HT neurons (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001; Bortolozzi et al., 2003). To reconcile these findings with the fact that the systemic administration of DOI decreased 5-HT neuronal activity, it has been proposed that the 5-HT2A-R agonist would activate cortical pyramidal neurons projecting on GABAergic interneurons in the DRN (Serrats et al., 2005). Insomuch as the activation of 5-HT2A-Rs modulates the firing rate of DRN 5-HT, such activation could also result in changes in 5-HT release at the nerve terminals. In agreement with the fact that activation of the 5-HT2A-Rs reduces the firing activity of DRN 5-HT neurons, it has been demonstrated that the systemic administration of DOI to chloral hydrate-anesthetized rats reduced the extracellular 5-HT concentrations in the mPFC, an effect antagonized by MDL100907 (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2001).

It should be also noted that 5-HT2A-Rs might also participate in the regulation of the dopaminergic system through either direct or indirect mechanisms. In the VTA, 5-HT2A-Rs have also been identified in GABAergic interneurons, and their activation lead to the inhibition of dopaminergic activity (Doherty and Pickel, 2000; Nocjar et al., 2002). On the other hand, 5-HT2A-Rs might also be expressed directly onto DA VTA neurons and their activation would stimulate dopaminergic activity (Bubar et al., 2011; Howell and Cunningham, 2015). Hence, it has been shown that the systemic administration or local application of DOI increased the firing rate and burst firing of DA neurons as well as DA release in both the VTA and mPFC (Bortolozzi et al., 2005).

These electrophysiological and neurochemical data provide, at least in part, explanations of the fact that AAPs with 5-HT2A-R antagonistic activity, display antidepressant properties and are effective adjuncts in depressed patients responding inadequately to SSRIs (Blier and Szabo, 2005; Blier and Blondeau, 2011). There is indeed compelling clinical evidence for antidepressant efficacy of AAPs (Ghaemi and Katzow, 1999; Ostroff and Nelson, 1999; Hirose and Ashby, 2002; Shelton et al., 2005; Thase et al., 2007) and in the last few years, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and quetiapine have obtained FDA approvals for treatment of resistant depression in combination with SSRIs (DeBattista and Hawkins, 2009). Accordingly, it might be hypothesized that the progressive therapeutic activity of chronic treatment with SSRIs would be accompanied by a downregulation of 5-HT2A-Rs (Meyer et al., 2001). However, this assumption is still cause for debate (Massou et al., 1997; Zanardi et al., 2001; Muguruza et al., 2014).

The 5-HT2A-Rs in the Regulation of Mood Related Behaviors and Antidepressant Response

Preclinical Studies

A multitude of studies have associated 5-HT2A-Rs activation with depressive-like phenotypes. In behavioral paradigms relevant to depression, DOI significantly increased immobility time in the mouse FST, and this effect was abolished by a pre-treatment with MDL100907 (Diaz and Maroteaux, 2011). These results raised the possibility that 5-HT2A-R antagonists might produce antidepressant-like activities. Consistent with this hypothesis, it was shown that antisense-mediated downregulation of the 5-HT2A-Rs decreased the immobility of mice in the FST (Sibille et al., 1997) or that the 5-HT2A-R antagonists EMD281014 or MDL100907 produced similar antidepressant-like effects in rats (Zaniewska et al., 2010). More recently, a novel 5-HT2A-R antagonist BIP-1 has been synthesized and its acute or sustained administration was also shown to produce antidepressant-like activities not only in basal conditions but also in bulbectomized rats (Pandey et al., 2010) suggesting that the inactivation of 5-HT2A-Rs may also produce beneficial effects in animal models of depression. In order to confirm these results, we recently investigated whether the genetic ablation of 5-HT2A-Rs (5-HT2A-/- mice) prevented chronic CORT-induced stress-related behavioral anomalies. Unexpectedly, the time of immobility in the TST was higher in 5-HT2A-/- than in 5-HT2A+/+ wild-type (WT) in response to CORT administration (Petit et al., 2014). These results can therefore be interpreted as an exaggerated despair in 5-HT2A-/- exposed to CORT. In this study, we did not find any basal modifications of despair in 5-HT2A-/- mice as previously reported (Weisstaub et al., 2006) but our results suggested that the genetic inactivation of the 5-HT2A-R subtype is an important process to potentiate the depressive-like effects of chronic CORT administration. In agreement with this hypothesis, preclinical studies reported that chronic treatment with CORT desensitized the 5-HT2A-Rs within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Lee et al., 2009), whereas repeated stress decreased their density in the hippocampus (Schiller et al., 2003; Dwivedi et al., 2005). The mechanism by which glucocorticoids might have a repressive role on the 5-HT2A-R subtype is presently unclear, but recent investigations propose that glucocorticoids receptors may act directly as transcription factors at critical site of the HTR2A gene promoter (Falkenberg et al., 2011). Further studies exploring the reciprocal relationships between the HPA and the 5-HT2A-Rs are clearly required to provide a better understanding of how their interactions relates to the development of depression.

Clinical Studies

Genetic association studies have focused on the genetic variants at the gene encoding for the 5-HT2A-Rs (Anguelova et al., 2003; Serretti et al., 2007). The association between MD and three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), G-to-A substitution at nucleotide -1438 (rs6311, -1438G/A), C-to-T substitution at nucleotide 102 (rs6313, 102C/T) and C-to-T substitution at nucleotide 1354 (rs6314, His452Tyr, 1354C/T) has been investigated, showing inconsistent results for the C allele of rs6313 (association: Zhang et al., 1997; Du et al., 2000; Arias et al., 2001a,b no association: Tsai et al., 1999; Minov et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2008; Illi et al., 2009; Kishi et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009), for the A allele of rs6311 (association: Enoch et al., 1999; Jansson et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006; Christiansen et al., 2007; Kamata et al., 2011, opposite association: Choi et al., 2004, no association: Ohara et al., 1998; Illi et al., 2009; Kishi et al., 2009; Tencomnao et al., 2010), and for rs6314 which has been poorly studied (no association: Minov et al., 2001). Moreover, the functional consequences of these SNPs on 5-HT2A-R function and/or HTR2A expression remain poorly studied (Serretti et al., 2007), especially the C allele of rs6313, which could be submitted to methylation, a process known to prevent gene expression (Polesskaya et al., 2006) and for the T allele of rs6314 which could be associated with a decreased 5-HT2A-R-mediated intracellular signaling (Ozaki et al., 1997). We recently reported genetic arguments supporting an association between specific HTR2A SNPs and both susceptibility and severity of major depressive episodes in MD. Indeed, depressed patients with allelic variants suspected to decrease the expression/function of the 5-HT2A-Rs, i.e., the C allele of rs6313 and the rare TT variant of rs6314, have an increased severity of major depressive episodes (Petit et al., 2014). In this sample of depressed patients, the over-representation of rs6313 C carriers suggests that this allele was associated with MD. Moreover, a higher severity of major depressive episodes observed in CT/CC patients as compared to TT patients further supports the association of 5-HT2A-Rs and MD. Interestingly, in this sample of depressed patients, two patients carrying the rare TT genotype (452Tyr/Tyr) of rs6314 had severe melancholic major depressive episodes, but such association has not been reproduced in a recent study (Gadow et al., 2014). This might be related to the fact that the TT genotype has reduced ability to activate G proteins, downstream of 5-HT2A-Rs (Hazelwood and Sanders-Bush, 2004). Interestingly, the association of 5-HT2A-Rs and MD has been mainly reported in severe forms of suicide, notably such with suicidal attempts (Du et al., 2000; Giegling et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006; Saiz et al., 2008; Vaquero-Lorenzo et al., 2008) or melancholic features (Akin et al., 2004). The latter clinical results are also in line with those showing a greater 5-HT2AR binding in post-mortem brain tissue (Yates et al., 1990; Hrdina et al., 1993; Arranz et al., 1994; Pandey et al., 2002; Shelton et al., 2009) or in platelets (Hrdina et al., 1995, 1997; Sheline et al., 1995) from individuals with MD, and those evidencing that 5-HT2A-Rs mediated phosphoinositide synthesis was reduced in fibroblasts from patients with melancholic depression compared to controls (Akin et al., 2004).

It is noteworthy that variations in the gene encoding for the 5-HT2A-R have also been associated with the treatment outcome of SSRIs in MD (Choi et al., 2005; McMahon et al., 2006; Kato et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2009; Wilkie et al., 2009; Kishi et al., 2010; Lucae et al., 2010; Viikki et al., 2011). In particular, a recent pharmacogenetic study also pointed out that specific SNPs related with 5-HT2A-R signaling pathways might influence the therapeutic activity of SSRIs in Chinese patients with MD (Li et al., 2012). Unfortunately, in most cases the consequences of these polymorphisms on 5-HT2A-R expression and/or function are lacking knowledge and evidence.

The 5-HT2A-Rs in the Regulation of Epilepsy and Antiepileptic Response

As we have highlighted in the previous paragraphs, 5-HT is an important neurotransmitter in the brain as it is involved in many neurological and psychiatric diseases including epilepsy. Serotonin receptors may directly or indirectly depolarize or hyperpolarize neurons by changing the ionic conductance and/or concentration within the cells (Barnes and Sharp, 1999). It is thus not surprising that 5-HT is able to change the excitability in most networks involved in epilepsy (Bagdy et al., 2007; Jakus and Bagdy, 2011; Gharedaghi et al., 2014).

Conventionally, epilepsy syndromes are classified into two distinct categories, focal and generalized, according to the seizure onset (arising from a specific brain area or from both hemispheres), the electroencephalogram and behavioral characteristics and the brain circuitry sustaining the paroxysms (Berg et al., 2010). Focal and generalized epilepsy differ also in the pathological neurochemical imbalance observed in the brain areas with a decrease and an increase of GABA function, respectively (Cope et al., 2009). This lead to a different therapeutic approach, indeed drugs that increase GABA concentration are first choice in focal/convulsive epilepsy and exacerbate absence epilepsy seizures. For instance, gabapentin, a structural GABA analog which increases GABA synthesis, is not indicated in generalized epilepsy syndromes (especially absence epilepsies), which it may exacerbate (Manning et al., 2003).

The majority of the focal and generalized seizures are convulsive (60%) while the remaining seizures are generalized non-convulsive. Moreover, since an obvious cell death or other tissue pathology is often absent, these epilepsies are idiopathic and typically associated with genetic abnormalities, an example of which is ASs (Crunelli and Leresche, 2002).

Here, we will focus on the focal TLE and the idiopathic generalized absence epilepsy. TLE is traditionally associated to many disorders localized to the cortex (neocortex and entorhinal cortex) and the hippocampal formation or both. Moreover, histological reports of TLE patients and animal models of epilepsy have consistently demonstrated that pathology is not limited to these areas but also to the thalamus, therefore the epileptogenic network in TLE is broad (Bernhardt et al., 2013). Typical ASs of idiopathic generalized epilepsies consist in sudden, brief periods of loss of consciousness which are accompanied by synchronous, generalized SWDs in the EEG (Crunelli and Leresche, 2002). SWDs originate from abnormal firing in thalamic and cortical networks and GABAA inhibition is integral to their appearance (Crunelli and Leresche, 2002; Cope et al., 2009).

The involvement of the serotonergic system in epilepsy was suggested in the late 1950s (Bonnycastle et al., 1957) and all the areas involved in epilespy receive 5-HT innervetion and express different 5-HT-Rs including 5-HT2A-Rs (Figure 1A). Furthermore, 5-HT is known to regulate a wide variety of focal and generalized seizures, including absence epilepsy both in human and in animal models (Favale et al., 2003; Bagdy et al., 2007; Lorincz et al., 2007; Jakus and Bagdy, 2011). In general, agents that elevate extracellular 5-HT levels, such as 5-hydroxytryptophan and 5-HT reuptake blockers, inhibit both focal (limbic) and generalized seizures (Prendiville and Gale, 1993; Yan et al., 1994). Conversely, depletion of brain 5-HT lowers the threshold to audiogenically, chemically, and electrically evoked convulsions (Statnick et al., 1996). More recently, increased threshold to kainic acid-induced seizures was observed in mice with genetically increased 5-HT levels (Tripathi et al., 2008). These findings are corroborated by data showing that mice lacking the 5-HT1A- (Sarnyai et al., 2000; Parsons et al., 2001), 5-HT2C- (Applegate and Tecott, 1998), 5-HT4- (Compan et al., 2004) and, 5-HT7-Rs (Witkin et al., 2007), but also rats knocked-down for the 5-HT2A-Rs by antisense oligonucleotide treatment (Van Oekelen et al., 2003) are extremely susceptible to chemical and electrical-induced seizures. Nevertheless, since only 5-HT2C-R KO mice are prone to spontaneous death from seizures (Tecott et al., 1995), and seizures have not been reported with pharmacological blockade of different 5-HT-Rs, adaptive changes involving different mechanisms may play a role in the low seizure thresholds observed in 5-HT-R KO mice. In general, therefore, it seems that serotonergic neurotransmission by activating different 5-HT-Rs suppresses neuronal network hyperexcitability and seizure activity (Bagdy et al., 2007), although opposite effects have also been reported, especially for 5-HT3-4-6-7-Rs (Gharedaghi et al., 2014).

The role of pharmacological activation of 5-HT2A-Rs in epilepsy modulation is far from being well-established, however, it might be an important potential target in light of the recent evidence that their activation might be not only be anticonvulsant but also capable of reducing seizure-related mortality due to SUDEP (Buchanan et al., 2014), the leading cause of death in patients with refractory epilepsy (Shorvon and Tomson, 2011). In addition, we have recently shown that mCPP and lorcaserin, two preferential 5-HT2C-R agonists with different pharmacological profiles (Fletcher and Higgins, 2011; Higgins et al., 2013), stop the elongation of MDA and AD induced by repetitive perforant path stimulation recorded at the level of the granular cells of the hippocampal DG acting in urethane-anesthetized rats, an effect that was not blocked by SB242084, a selective 5-HT2C-R antagonist (Orban et al., 2014). The elongation of the MDA has been considered an electroencephalographic representation of epileptogenic phenomena occurring after the first electric insult (Stringer et al., 1989; Orban et al., 2013). Interestingly, preliminary results from our laboratory seem to indicate that mCPP and lorcaserin effects on MDA elongation might be due to the activation of 5-HT2A-rather than 5-HT2C-Rs since they were blocked by 5-HT2A-R antagonists while the 5-HT2A-R agonist TCB-2 mimicked mCPP and lorcaserin effects (unpublished observations). Conversely, evidence from other groups showed that DOI strongly facilitated kindling development and reduced the number of stimulations needed to produce generalized seizures in the amygdaloid kindled rats (Wada et al., 1997) while it was ineffective in any parameters on hippocampal partial seizures generated by low-frequency electrical stimulation of the hippocampus in rats (Watanabe et al., 1998). Similarly, Wada et al. (1992) showed that in the feline hippocampal kindled seizures, DOI had no effect displaying only a tendency to be anti-epileptic, decreasing the duration of AD and generalized tonic–clonic convulsions, although not significantly. In the same model, the selective 5-HT2A-R antagonist MDL100907, had no effect on seizure thresholds, secondary AD duration or latency of secondary AD (Watanabe et al., 2000). However, the 1 mg/kg dose of MDL100907 significantly increased the primary AD duration, suggesting that at this dose MDL100907 increased seizure severity in this model, although high AD control levels might have invalidated the 5-HT2A-R antagonist effect (Watanabe et al., 2000). The 5-HT2A/2C-R antagonist ketanserin and the more selective 5-HT2A-R antagonist ritanserin decrease the threshold for seizures maximal electroshock threshold (MEST) test in mice (Przegaliński et al., 1994). In other experimental models, 5-HT2A-R antagonists have failed to be effective in seizure control. Ritanserin was ineffective on kainic acid-induced seizures (Velisek et al., 1994) and ketanserin did not affect the seizure threshold for picrotoxin in mice (Pericic et al., 2005) or on ethanol withdrawal seizures (Grant et al., 1994), but antagonized cocaine-induced convulsions in a dose-dependent manner (Ritz and George, 1997). The 5-HT2A/2C-R and calcium antagonist dotarizine inhibited electroconvulsive shock (ECS)-induced seizures but had no effect on pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced convulsions in rats (Lazarova et al., 1995) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Role of the 5-HT2A receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy.

| Model | Effect | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiepileptic role of the 5-HT2A receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy | ||||

| Antagonists | MDL 11,939 (5-HT2A) | MEST test in Lmx1bf/f/p mice | Blocked DOI-TCB-2 effect in preventing seizure-induced respiratory arrest and death | Buchanan et al. (2014) |

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A) | MEST test in mice | Decreases the threshold for seizures | Przegaliński et al. (1994) | |

| Ritanserin (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | MEST test in mice | Decreases the threshold for seizures | ||

| MDL 100907 (5-HT2A) | Electroshock-induced hippocampal partial seizures in rats | Increases primary AD duration | Watanabe et al. (2000) | |

| Agonists | DOI (5-HT2A/2C) TCB-2 (5-HT2A) | MEST test in Lmx1bf/f/p mice | Prevented seizure-induced respiratory arrest and death | Buchanan et al. (2014) |

| mCPP (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | MDA in rats | Stop MDA elongation (not blocked by SB242084) | Orban et al. (2014) | |

| Lorcaserin (5-HT2B/2C) | MDA in rats | Stop MDA elongation (not blocked by SB242084) | ||

| DOI (5-HT2A/2C) | Hippocampal kindled seizures in rats | Reduces AD duration | Wada et al. (1992) | |

| Pro-epileptic role of the 5-HT2A receptors | ||||

| Antagonists | Antisense oligonucleotide designed to inhibit 5-HT2A expression | Tryptamine-induced serotonergic syndrome-associated convulsions | Inhibited tryptamine-induced bilateral convulsions and body tremors | Van Oekelen et al. (2003) |

| MDL100907 (5-HT2A) | Feline hippocampal kindled seizures | No effect on seizure thresholds, secondary AD duration, or latency of secondary AD | Watanabe et al. (2000) | |

| Ritanserin (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | Kainic acid-induced seizures in rats | Has no effect | Velisek et al. (1994) | |

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A) | Cocaine-induced convulsions in mice | Dose-dependently inhibits seizures | Ritz and George (1997) | |

| Hippocampal kindled seizures in cats | Increases latency to generalized convulsions | Wada et al. (1992) | ||

| Amygdala kindling in rats | Delays the development of kindling | Wada et al. (1997) | ||

| Picrotoxin-induced seizures in stressed and unstressed mice | Has no effect on seizure thresholds | Pericic et al. (2005) | ||

| Ethanol-withdrawal seizures in mice | Has no effect on seizure severity | Grant et al. (1994) | ||

| Cinanserin (5-HT2A/2C) | Cocaine-induced convulsions in mice | Dose-dependently inhibits seizures | Ritz and George (1997) | |

| Pirenperone (5-HT2A/2C) | Cocaine-induced convulsions in mice | Dose-dependently inhibits seizures | ||

| Dotarizine (5-HT2A/2C) | Electroshock-induced seizures in rats | Increases the threshold for seizures | Lazarova et al. (1995) | |

| PTZ-induced seizures in rats | Has no effect on seizure thresholds | |||

| Agonists | DOI (5-HT2A/2C) | Hippocampal kindled seizures in cats | Decreases latency to generalized convulsions | Wada et al. (1992) |

| Amygdala kindling in rats | Facilitates kindling and reduces the number of stimulations needed to elicit generalized convulsions | Wada et al. (1997) | ||

| Picrotoxin-induced seizures in stressed and unstressed mice | Has no effect on seizure thresholds | Pericic et al. (2005) |

MEST, maximal electroshock threshold; PTZ, pentylenetetrazole; SE, status epilepticus.

As far as the 5-HT control of generalized ASs is concerned, most of the limited available evidence has been obtained in WAG/Rij rats, with 5-HT1A-, 5-HT2C-, and 5-HT7-Rs appearing as the most critical for the expression of this form of epilepsy (Bagdy et al., 2007). Briefly, activation or inhibition of 5-HT1A- and 5-HT7-Rs increases or decreases ASs, respectively, while 5-HT2C-R agonists are effective in inhibiting epileptiform activity and 5-HT2C-R antagonism lacks any effects (Jakus et al., 2003; Jakus and Bagdy, 2011). In agreement with this evidence, fluoxetine, and citalopram caused a moderate increase in SWDs; potentiated or inhibited by pre-treatment with SB-242084 and the 5-HT1A-R antagonist WAY-100635, respectively (Jakus and Bagdy, 2011). The role of 5-HT2A-Rs has not instead been investigated in WAG/Rij rats yet. In another genetic animal model of absence epilepsy, the groggy (GRY) rats, increasing 5-HT levels by treatment with the 5-HT reuptake inhibitors fluoxetine and clomipramine, inhibits SWD generation, an effect mimicked by DOI and blocked by ritanserin pre-treatment (Ohno et al., 2010). Consistently, in atypical ASs induced by AY-9944, DOI reduced the total duration and number of SWDs, and ketanserin exacerbated the number of SWDs. On the other hand, in contrast to the evidence obtained in WAG/Rij rats, 5-HT2C-R activation by mCPP had no effect on total duration or number of SWD in this model of atypical absence epilepsy (Bercovici et al., 2007).

In contrast to these findings, however, earlier evidence had shown that serotonergic neurotransmission and 5-HT2A-Rs do not appear to be involved in the pathogenesis or control of ASs in the most widely used rat model of absence epilepsy, the GAERS (Danober et al., 1998) (Table 2). Although this discrepancy could be simply due to differences between the two experimental models, it is more likely explained by the lack of selectively of the serotoninergic drugs that were used in the earlier study in GAERS. The role of 5-HT, and especially the different areas in which the modulation of ASs might occur, has not been examined thoroughly and it is currently object of investigation in our laboratories. Since we have recently shown that an aberrant eGABA function in VB neurons is a necessary factor in the expression of SWDs associated with typical absence epilepsy (Cope et al., 2009; Di Giovanni et al., 2011; Errington et al., 2011, 2014), it is conceivable that some of the systemically injected 5-HT ligand effects on ASs (Danober et al., 1998; Isaac, 2005; Bagdy et al., 2007; Bercovici et al., 2007; Ohno et al., 2010) occur via a modulation of tonic GABAA inhibition. This hypothesis is based also on the evidence that DA and especially the activation of D2-Rs decreases both ASs (Deransart et al., 2000) and eGABA current in GAERS VB neurons (Yague et al., 2013; Crunelli and Di Giovanni, 2014). Indeed, our preliminary results show that 5-HT2A-R ligands lack any effect on phasic synaptic GABAA inhibition in VB thalamocortical neurons of Wistar rats (Cavaccini et al., 2012), while 5-HT2A-R selective agonists significantly enhanced the tonic eGABAA conductance. This enhancement of eGABAA tonic current was blocked by co-application of 5-HT2A-R antagonists which were devoid of any effect per se. Strikingly, 5-HT2A-R antagonists were instead effective in decreasing the aberrant GABAA tonic current in GAERS. From these findings, we can speculate that the activation of the 5-HT2A-Rs would have a pro-epileptic activity, although this evidence has not been obtained yet in vivo.

Table 2.

Role of the 5-HT2A receptors in absence epilepsy.

| Model | Effect | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical absence epilepsy | Agonists | DOI (5-HT2A/2C) | GRY rats | Inhibits SWDs | Ohno et al. (2010) |

| m-CPP (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | WAG/Rij rats | Decreases the duration and frequency of SWDs | Jakus et al. (2003) | ||

| Antagonists | Ritanserin (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | GRY | Increases SWDs | Ohno et al. (2010) | |

| Ritanserin (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | GAERS | Has no effect | Marescaux et al. (1992) | ||

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A) | GAERS | Has no effect | |||

| Atypical absence epilepsy | Agonists | DOI (5-HT2A/2C) | AY-9944 rats | Reduces the frequency and duration of slow SWDs | Bercovici et al. (2007) |

| Antagonists | m-CPP (5-HT2A/2B/2C) | AY-9944 rats | Has no effect | Bercovici et al. (2007) | |

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A) | AY-9944 rats | Increases the frequency and duration of slow SWDs | Bercovici et al. (2007) |

GRY, groggy, WAG/Rij, Wistar Albino Glaxo rats from Rijswijk; SWD, spike-wave discharge; GAERS, Genetic Absence Epilepsy in Rats from Strasbourg; AY-9944, trans-N, N-bis[2-chlorophenylmethyl]-1,4-cyclohexanedimethanamine dihydrochloride. Modified from Gharedaghi et al. (2014).

There is evidence indicating that 5-HT2A-R activation potentiates the inhibitory effect of lamotrigine, a widely used antiepileptic agent, on voltage-gated sodium channels (Than et al., 2007). Lamotrigine is the only other antiepileptic drug (AED) with clear benefit for bipolar disorder, and is approved by FDA for maintenance treatment (Bowden et al., 2003). Interestingly, a study in Long-Evans rats with spontaneous SWDs has indicated that chronic lamotrigine treatment can benefit patients with absence epilepsy via suppression of seizures and amelioration of comorbid anxiety and depression (Huang et al., 2012).

Further, some ligand-binding studies in animals have shown that the antiepileptic valproate increases 5-HT2A-R expression (Green et al., 1985; Sullivan et al., 2004), although an in vivo imaging study has not confirmed it in acute mania (Yatham et al., 2005). This study, however, cannot exclude the possibility that valproate improves mood symptoms by altering second messenger signaling cascades linked to 5-HT2A-Rs. Indeed, brain 5-HT2A-Rs are coupled via G-proteins to phosphoinositol pathway, and there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that both valproate and lithium have multiple effects on this pathway (Brown and Tracy, 2013).

The abovementioned studies show that generally 5-HT has an anticonvulsant effect in both generalized and focal epilepsy and the 5-HT2-Rs appear to play a major role, although contrasting evidence also exists. In particular, the anti- versus pro-epileptic effects of the 5-HT2A-Rs might depend on the dose of the ligands used, with pro-convulsive effects when the receptors are excessively activated, the experimental model investigated and different populations of receptors. Moreover, at high doses, the selectivity of these ligands is lost and other mechanisms cannot be ruled out.

More research is needed to clarify the role of 5-HT2A-Rs in seizures especially in absence epilepsy. Thus, increasing our understanding of the role of 5-HT2A-Rs and their modulation of other neurotransmitter systems such as GABA might reveal a new possible therapeutic mechanism with potential translational significance.

Do the 5-HT2A-Rs Play a Role in the Comorbidity between Epilepsy and Depression?

It is estimated that between 15 and 30% of people with epilepsy develop several psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and different levels of cognitive impairments (Stafford-Clark, 1954; Kanner and Balabanov, 2002; Kanner, 2003). The patients with partial complex epilepsy, such as TLE, or who have poorly controlled epilepsy have the highest frequency rate of comorbid affective disorders (Kanner et al., 2012). Besides, depression-like behavior has also been found in generalized epilepsy such as childhood absence epilepsy (Vega et al., 2011). This clear link between epilepsy, comorbid psychiatric disorders and monoaminergic and specifically serotoninergic dysfunction has been also observed in humans (Harden, 2002) and different animal models of epilepsy (Sarkisova and van Luijtelaar, 2012; Epps and Weinshenker, 2013). Moreover, the animal and human evidence has revealed that the relationship between depression and epilepsy is in reality bidirectional. Indeed patients with depression and especially suicide attempters have an increased seizure risk compared to the normal population (Hesdorffer et al., 2006). Thus, the fact that epilepsy and depression may share common pathogenic mechanisms and dysfunction of the serotonergic system is an obvious explanation for this bidirectional comorbidity, since defects in the serotonergic system are linked to both conditions (Epps et al., 2012; Epps and Weinshenker, 2013). In agreement, we have showed further evidence of the involvement of both serotonergic and dopaminergic systems in the pathogenesis of epilepsy (Cavaccini et al., 2012; Orban et al., 2013; Yague et al., 2013; Connelly et al., 2014; Crunelli and Di Giovanni, 2014; Orban et al., 2014), in depression and its pharmacological treatments (Di Giovanni, 2008; Esposito et al., 2008). Compelling evidence for the involvement of 5-HT1A- and 5-HT7-Rs in epilepsy and depression has been described, therefore it is possible to infer that agonists at these receptors might have both antiepileptic and antidepressant activity with also cognitive enhancer efficacy (Orban et al., 2013). On the other hand, the role of the other 5-HT2A-Rs has been less investigated, and this field is still in its infancy with many issues that still need to be addressed. Regarding the 5-HT2A-R as a drug target for treating depression and epilepsy, it has recently been shown in WAG/Rij rats that sub-chronic treatment with aripiprazole, a new antipsychotic with antagonism at 5-HT2A/5-HT6-Rs and also partial agonism at D2 DA and 5-HT1A and 5-HT7-Rs, has an anti-AS effect, and positive modulatory actions on depression, anxiety, and memory which might also be beneficial in other epileptic syndromes (Russo et al., 2013). Nevertheless, this study did not identify which receptor subtype underlined these promising aripiprazole therapeutic properties. Perhaps, the 5-HT-Rs more directly linked with the antidepressant and antiepileptic effects of aripiprazole might be the 5-HT1A/7-Rs, in light of the well-known effects of clozapine on seizures. Clozapine, the first AAP to be developed with some 5-HT2A-R antagonist effects, increases seizure risk even at therapeutic serum levels (Hedges et al., 2003) and it is indeed the only psychotropic drug to have received a FDA black box warning regarding seizures.

Improved seizure control has also been observed in epileptic patients treated for psychiatric disorders with antidepressants elevated extracellular serotonin in the epileptic foci can lead to an anticonvulsant effect (Specchio et al., 2004), but the contribution of the single 5-HT-Rs has not yet been revealed.

As far as cognitive impairments are regarded, preclinical studies have shown that the 5-HT2A-R activation also has some therapeutic benefits. For instance, ketanserin inhibited the impairment of short-term memory which is seen after seizures studied by spontaneous alternation rat behavior in the Y-maze task (Hidaka et al., 2010). In addition, ketanserin inhibited ECS-induced retrograde amnesia in the step-down passive avoidance task, suggesting that 5-HT2A-Rs impede consolidation and/or retrieval of memory after seizures (Genkova-Papazova et al., 1994) (Table 3).

Table 3.

5-HT2A receptors in comorbidity between epilepsy and depression.

| Model | Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamotrigine | Chronic pain states in rats | + m-CPP (5-HT2A/2B/2C) increased the reflex inhibitory action of lamotrigine | Than et al. (2007) |

| Lamotrigine | Chronic pain states in rats | Decreased the reflex inhibitory action of + Ketanserin (5-HT2A) lamotrigine | |

| Lamotrigine | Humans | Bipolar disorders | Bowden et al. (2003) |

| Lamotrigine | WAG/Rij rats | Suppression of AS and amelioration of comorbid anxiety and depression | Huang et al. (2012) |

| Aripiprazole (5-HT2A/5-HT6 antagonist) | WAG/Rij rats | Suppression of AS amelioration of comorbid anxiety depression and memory impairment | Russo et al. (2013) |

| Valproate | Humans | Increases 5-HT2A-R expression | Green et al. (1985); Sullivan et al. (2004) |

| Valproate | ECS | Inhibited impairment of spontaneous alternation behavior | Hidaka et al. (2011) |

| SSRIs (5-HT-R?) | Different models | Anticonvulsant | Specchio et al. (2004) |

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A antagonist) | ECS | Inhibited the impairment of short-term memory | Hidaka et al. (2010) |

| Ketanserin (5-HT2A antagonist) | ECS | Inhibited electroconvulsive shock-induced retrograde amnesia | Genkova-Papazova et al. (1994) |

WAG/Rij, Wistar Albino Glaxo rats from Rijswijk; ECS, electroconvulsive shock.

Summarizing, both agonists and antagonists appear to be useful in epilepsy treatment (Tables 1 and 2). These paradoxical actions of 5-HT2A antagonists and agonists can be reconciled taking in to consideration that both agonism and antagonism induce 5-HT2A-Rs desensitization or downregulation (Gray and Roth, 2001). The main hindrance for the development of 5-HT2A-R agonists is the hallucinogenic effects (Krebs-Thomson et al., 1998). New 5-HT2A compounds with higher selectivity and which lack these aversive side effects are needed.

Conclusion

Together, the observations reviewed here support an important role for 5-HT2A-Rs in both affective disorders and normal and pathologic neuronal excitability. The available literature suggests that the antagonism at 5-HT2AR might have beneficial effects on both disorders. Moreover, 5-HT2A-R antagonists might represent a new therapeutic strategy in epileptic patients with comorbid depression and cognitive dysfunctions. In addition, 5-HT2A-R antagonism may improve the effectiveness of medical therapy with respect to seizure control for both focal and generalized seizures if they are combined with existing AEDs and/or SSRIs. The pathophysiology of depression and epilepsy might result, at least in part, directly from a dysregulation of brain serotonin 2A neurotransmission or indirectly from the dysfunction of other neurotransmitter systems (i.e., dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic) that are under 5-HT2A control. Needless to say, it remains to be determined whether epilepsy and its comorbid psychiatric disorders are instead mere epiphenomena of the primary alteration of 5-HT2A-R signaling.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Malta Council of Science and technology, R&I-2013-14 (GDG) and EU COST Action CM1103 (GDG).

Abbreviations

- AAP

atypical antipsychotic

- AD

after discharge

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin

- 5-HT2A-Rs

serotonin 2A receptors

- ASs

absence seizures

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CORT

corticosterone

- DA

dopamine

- DG

dentate gyrus

- DOI

2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine

- DRN

dorsal raphe nucleus

- eGABA

extrasynaptic GABAA

- FST

forced swim test

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GAERS

Genetic Absence Epilepsy in Rats from Strasbourg

- GPCRs

G protein-coupled receptors

- LC

locus coeruleus

- MD

major depression

- MDA

maximal dentate activation

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- MRN

medial raphe nucleus

- NE

norepinephrine

- PAG

periaqueductal gray

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- SUDEP

sudden unexpected death in epilepsy

- SWDs

spike and wave discharges

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

- TST

tail suspension test

- VB

ventrobasal thalamus

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

REFERENCES

- Abbas A., Roth B. L. (2008). Arresting serotonin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 831–832 10.1073/pnas.0711335105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Saab W. M., Bubser M., Roth R. H., Deutch A. Y. (1999). 5-HT2 receptor regulation of extracellular GABA levels in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 20 92–96 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian G. K., Marek G. J. (1997). Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology 36 589–599 10.1016/S0028-3908(97)00051-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian G. K., Marek G. J. (1999). Serotonin, via 5-HT2A receptors, increases EPSCs in layer V pyramidal cells of prefrontal cortex by an asynchronous mode of glutamate release. Brain Res. 825 161–171 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01224-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin D., Manier D. H., Sanders-Bush E., Shelton R. C. (2004). Decreased serotonin 5-HT2A receptor-stimulated phosphoinositide signaling in fibroblasts from melancholic depressed patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 29 2081–2087 10.1038/sj.npp.1300505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albizu L., Holloway T., Gonzalez-Maeso J., Sealfon S. C. (2011). Functional crosstalk and heteromerization of serotonin 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 receptors. Neuropharmacology 61 770–777 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amargos-Bosch M., Artigas F., Adell A. (2005). Effects of acute olanzapine after sustained fluoxetine on extracellular monoamine levels in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 516 235–238 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amargos-Bosch M., Bortolozzi A., Puig M. V., Serrats J., Adell A., Celada P., et al. (2004). Co-expression and in vivo interaction of serotonin1A and serotonin2A receptors in pyramidal neurons of prefrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 14 281–299 10.1093/cercor/bhg128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelova M., Benkelfat C., Turecki G. (2003). A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: I. Affective disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 8 574–591 10.1038/sj.mp.4001328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate C. D., Tecott L. H. (1998). Global increases in seizure susceptibility in mice lacking 5-HT2C receptors: a behavioral analysis. Exp. Neurol. 154 522–530 10.1006/exnr.1998.6901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias B., Gasto C., Catalan R., Gutierrez B., Pintor L., Fananas L. (2001a). The 5-HT(2A) receptor gene 102T/C polymorphism is associated with suicidal behavior in depressed patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. 105 801–804 10.1002/ajmg.10099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias B., Gutierrez B., Pintor L., Gasto C., Fananas L. (2001b). Variability in the 5-HT(2A) receptor gene is associated with seasonal pattern in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 6 239–242 10.1038/sj.mp.4000818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arranz B., Eriksson A., Mellerup E., Plenge P., Marcusson J. (1994). Brain 5-HT1A, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT2 receptors in suicide victims. Biol. Psychiatry 35 457–463 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanov V. L., Liang X., Russo A., Wang R. Y. (1999). LSD and DOB: interaction with 5-HT2A receptors to inhibit NMDA receptor-mediated transmission in the rat prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11 3064–3072 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00726.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby C. R., Jr., Jiang L. H., Kasser R. J., Wang R. Y. (1990). Electrophysiological characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine2 receptors in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 252 171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdy E., Kiraly I., Harsing L. G., Jr. (2000). Reciprocal innervation between serotonergic and GABAergic neurons in raphe nuclei of the rat. Neurochem. Res. 25 1465–1473 10.1023/A:1007672008297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdy G., Kecskemeti V., Riba P., Jakus R. (2007). Serotonin and epilepsy. J. Neurochem. 100 857–873 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban J. M., Aghajanian G. K. (1980). Suppression of firing activity of 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphe by alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology 19 355–363 10.1016/0028-3908(80)90187-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. M., Sharp T. (1999). A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38 1083–1152 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercovici E., Cortez M. A., Snead O. C., III. (2007). 5-HT2 modulation of AY-9944 induced atypical absence seizures. Neurosci. Lett. 418 13–17 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg A. T., Berkovic S. F., Brodie M. J., Buchhalter J., Cross J. H., van Emde Boas W., et al. (2010). Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE commission on classification and terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 51 676–685 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt B. C., Hong S., Bernasconi A., Bernasconi N. (2013). Imaging structural and functional brain networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7:624 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P., Blondeau C. (2011). Neurobiological bases and clinical aspects of the use of aripiprazole in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 128(Suppl. 1), S3–S10 10.1016/S0165-0327(11)70003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P., Szabo S. T. (2005). Potential mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic medications in treatment-resistant depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66(Suppl. 8), 30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi C. (2012). Neuronal localization of 5-HT2A receptor immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal region. Brain Res. Bull. 87 259–273 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnycastle D. D., Giarman N. J., Paasonen M. K. (1957). Anticonvulsant compounds and 5-hydroxytryptamine in rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 12 228–231 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1957.tb00125.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman L. J., Allers K. A., Rasmussen K., Sharp T. (2003). Evidence that central 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B/C receptors regulate 5-HT cell firing in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the anaesthetised rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139 998–1004 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman L. J., Sharp T. (2005). A role for midbrain raphe gamma aminobutyric acid neurons in 5-hydroxytryptamine feedback control. Neuroreport 16 891–896 10.1097/00001756-200506210-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolozzi A., Amargos-Bosch M., Adell A., Diaz-Mataix L., Serrats J., Pons S., et al. (2003). In vivo modulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine release in mouse prefrontal cortex by local 5-HT(2A) receptors: effect of antipsychotic drugs. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18 1235–1246 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolozzi A., Diaz-Mataix L., Scorza M. C., Celada P., Artigas F. (2005). The activation of 5-HT receptors in prefrontal cortex enhances dopaminergic activity. J. Neurochem. 95 1597–1607 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden C. L., Calabrese J. R., Sachs G., Yatham L. N., Asghar S. A., Hompland M., et al. (2003). A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60 392–400 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brea J., Castro M., Giraldo J., Lopez-Gimenez J. F., Padin J. F., Quintian F., et al. (2009). Evidence for distinct antagonist-revealed functional states of 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor homodimers. Mol. Pharmacol. 75 1380–1391 10.1124/mol.108.054395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. M., Tracy D. K. (2013). Lithium: the pharmacodynamic actions of the amazing ion. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 3 163–176 10.1177/2045125312471963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubar M. J., Stutz S. J., Cunningham K. A. (2011). 5-HT(2C) receptors localize to dopamine and GABA neurons in the rat mesoaccumbens pathway. PLoS ONE 6:e20508 10.1371/journal.pone.0020508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan G. F., Murray N. M., Hajek M. A., Richerson G. B. (2014). Serotonin neurones have anti-convulsant effects and reduce seizure-induced mortality. J. Physiol. 592 4395–4410 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.277574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaccini A., Yagüe J. G., Errington A. C., Crunelli V., Di Giovanni G. (2012). Opposite effects of thalamic 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor activation on tonic GABA-A inhibition: implications for absence epilepsy. Ann. Meet. Neurosci. Soc. 29 1–119 [Google Scholar]

- Celada P., Puig M. V., Artigas F. (2013). Serotonin modulation of cortical neurons and networks. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 7:25 10.3389/fnint.2013.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. J., Kang R. H., Ham B. J., Jeong H. Y., Lee M. S. (2005). Serotonin receptor 2A gene polymorphism (-1438A/G) and short-term treatment response to citalopram. Neuropsychobiology 52 155–162 10.1159/000087847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. J., Lee H. J., Lee H. J., Ham B. J., Cha J. H., Ryu S. H., et al. (2004). Association between major depressive disorder and the -1438A/G polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene. Neuropsychobiology 49 38–41 10.1159/000075337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen L., Tan Q., Iachina M., Bathum L., Kruse T. A., Mcgue M., et al. (2007). Candidate gene polymorphisms in the serotonergic pathway: influence on depression symptomatology in an elderly population. Biol. Psychiatry 61 223–230 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compan V., Zhou M., Grailhe R., Gazzara R. A., Martin R., Gingrich J., et al. (2004). Attenuated response to stress and novelty and hypersensitivity to seizures in 5-HT4 receptor knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 24 412–419 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2806-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly W. M., Errington A. C., Yague J. G., Cavaccini A., Crunelli V., Di Giovanni G. (2014). “GPCR modulation of extrasynapitic GABAA receptors,” in Extrasynaptic GABAA Receptors, eds Errington A. C., Di Giovanni G., Crunelli V. (New York: Springer; ), 125–153 10.1007/978-1-4939-1426-5_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cope D. W., Di Giovanni G., Fyson S. J., Orbán G., Errington A. C., Lörincz M. L., et al. (2009). Enhanced tonic GABAA inhibition in typical absence epilepsy. Nat. Med. 15 1392–1398 10.1038/nm.2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornea-Hebert V., Riad M., Wu C., Singh S. K., Descarries L. (1999). Cellular and subcellular distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the central nervous system of adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 409 187–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V., Di Giovanni G. (2014). Monoamine modulation of tonic GABA(A) inhibition. Rev. Neurosci. 25 195–206 10.1515/revneuro-2013-0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V., Leresche N. (2002). Childhood absence epilepsy: genes, channels, neurons and networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 371–382 10.1038/nrn811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danober L., Deransart C., Depaulis A., Vergnes M., Marescaux C. (1998). Pathophysiological mechanisms of genetic absence epilepsy in the rat. Prog. Neurobiol. 55 27–57 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00091-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida J., Mengod G. (2007). Quantitative analysis of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons expressing 5-HT(2A) receptors in human and monkey prefrontal cortex. J. Neurochem. 103 475–486 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBattista C., Hawkins J. (2009). Utility of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of resistant unipolar depression. CNS Drugs 23 369–377 10.2165/00023210-200923050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delille H. K., Becker J. M., Burkhardt S., Bleher B., Terstappen G. C., Schmidt M., et al. (2012). Heterocomplex formation of 5-HT2A-mGlu2 and its relevance for cellular signaling cascades. Neuropharmacology 62 2184–2191 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Sergio T., De Bortoli V. C., Zangrossi H., Jr. (2011). Serotonin-2A receptor regulation of panic-like behavior in the rat dorsal periaqueductal gray matter: the role of GABA. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 218 725–732 10.1007/s00213-011-2369-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deransart C., Riban V., Le B., Marescaux C., Depaulis A. (2000). Dopamine in the striatum modulates seizures in a genetic model of absence epilepsy in the rat. Neuroscience 100 335–344 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00266-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G. (2008). New ligands at 5-HT and DA receptors for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 8 1005–1007 10.2174/156802608785161411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G. (2013). Serotonin in the pathophysiology and treatment of CNS disorders. Exp. Brain Res. 230 371–373 10.1007/s00221-013-3701-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G., Errington A. C., Crunelli V. (2011). Pathophysiological role of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in typical absence epilepsy. Malta Med. J. 23 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S. L., Maroteaux L. (2011). Implication of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the serotonin syndrome. Neuropharmacology 61 495–502 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M. D., Pickel V. M. (2000). Ultrastructural localization of the serotonin 2A receptor in dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 864 176–185 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02062-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dremencov E., El Mansari M., Blier P. (2007). Noradrenergic augmentation of escitalopram response by risperidone: electrophysiologic studies in the rat brain. Biol. Psychiatry 61 671–678 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Bakish D., Lapierre Y. D., Ravindran A. V., Hrdina P. D. (2000). Association of polymorphism of serotonin 2A receptor gene with suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 96 56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y., Mondal A. C., Payappagoudar G. V., Rizavi H. S. (2005). Differential regulation of serotonin (5HT)2A receptor mRNA and protein levels after single and repeated stress in rat brain: role in learned helplessness behavior. Neuropharmacology 48 204–214 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch M. A., Goldman D., Barnett R., Sher L., Mazzanti C. M., Rosenthal N. E. (1999). Association between seasonal affective disorder and the 5-HT2A promoter polymorphism, -1438G/A. Mol. Psychiatry 4 89–92 10.1038/sj.mp.4000439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps S. A., Tabb K. D., Lin S. J., Kahn A. B., Javors M. A., Boss-Williams K. A., et al. (2012). Seizure susceptibility and epileptogenesis in a rat model of epilepsy and depression co-morbidity. Neuropsychopharmacology 37 2756–2763 10.1038/npp.2012.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps S. A., Weinshenker D. (2013). Rhythm and blues: animal models of epilepsy and depression comorbidity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85 135–146 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington A.C., Di Giovanni G., Crunelli V. (eds) (2014). Extrasynapitic GABAA Receptors. New York: Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4939-1426-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Errington A. C., Gibson K. M., Crunelli V., Cope D. W. (2011). Aberrant GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibition in cortico-thalamic networks of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficient mice. PLoS ONE 6:e19021 10.1371/journal.pone.0019021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito E., Di Matteo V., Di Giovanni G. (2008). Serotonin-dopamine interaction: an overview. Prog. Brain Res. 172 3–6 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00901-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg V. R., Gurbaxani B. M., Unger E. R., Rajeevan M. S. (2011). Functional genomics of serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A): interaction of polymorphism, methylation, expression and disease association. Neuromol. Med. 13 66–76 10.1007/s12017-010-8138-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favale E., Audenino D., Cocito L., Albano C. (2003). The anticonvulsant effect of citalopram as an indirect evidence of serotonergic impairment in human epileptogenesis. Seizure 12 316–318 10.1016/S1059-1311(02)00315-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher A., Higgins G. A. (2011). “Serotonin and reward-related behaviour: focus on 5-HT2C receptors,” in 5-HT2C Receptors in the Pathophysiology of CNS Disease, eds Di Giovanni G., Esposito E., Di Matteo V. (New York: Springer; ), 293–324 10.1007/978-1-60761-941-3_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fribourg M., Moreno J. L., Holloway T., Provasi D., Baki L., Mahajan R., et al. (2011). Decoding the signaling of a GPCR heteromeric complex reveals a unifying mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs. Cell 147 1011–1023 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow K. D., Smith R. M., Pinsonneault J. K. (2014). Serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) regulatory variants: possible association with severity of depression symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 27 107–116 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardier A. M., Malagie I., Trillat A. C., Jacquot C., Artigas F. (1996). Role of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the mechanism of action of serotoninergic antidepressant drugs: recent findings from in vivo microdialysis studies. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 10 16–27 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garratt J. C., Kidd E. J., Wright I. K., Marsden C. A. (1991). Inhibition of 5-hydroxytryptamine neuronal activity by the 5-HT agonist, DOI. Eur. J. Pharmacol 199 349–355 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90499-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber E. I., Kroeze W. K., Willins D. L., Gray J. A., Sinar C. A., Hyde E. G., et al. (1999). Structure and function of the third intracellular loop of the 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor: the third intracellular loop is alpha-helical and binds purified arrestins. J. Neurochem. 72 2206–2214 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genkova-Papazova M., Lazarova-Bakarova M., Petkov V. D. (1994). The 5-HT2 receptor antagonist ketanserine prevents electroconvulsive shock- and clonidine-induced amnesia. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 49 849–852 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90233-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervasoni D., Peyron C., Rampon C., Barbagli B., Chouvet G., Urbain N., et al. (2000). Role and origin of the GABAergic innervation of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 20 4217–4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi S. N., Katzow J. J. (1999). The use of quetiapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a case series. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 11 137–140 10.3109/10401239909147062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharedaghi M. H., Seyedabadi M., Ghia J. E., Dehpour A. R., Rahimian R. (2014). The role of different serotonin receptor subtypes in seizure susceptibility. Exp. Brain Res. 232 347–367 10.1007/s00221-013-3757-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giegling I., Hartmann A. M., Moller H. J., Rujescu D. (2006). Anger- and aggression-related traits are associated with polymorphisms in the 5-HT-2A gene. J. Affect. Disord. 96 75–81 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocho Y., Sakai A., Yanagawa Y., Suzuki H., Saitow F. (2013). Electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of GABAergic cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus. J. Physiol. Sci. 63 147–154 10.1007/s12576-012-0250-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J. (2014). Family a GPCR heteromers in animal models. Front. Pharmacol. 5:226 10.3389/fphar.2014.00226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J., Ang R. L., Yuen T., Chan P., Weisstaub N. V., Lopez-Gimenez J. F., et al. (2008). Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature 452 93–97 10.1038/nature06612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Maeso J., Weisstaub N. V., Zhou M., Chan P., Ivic L., Ang R., et al. (2007). Hallucinogens recruit specific cortical 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated signaling pathways to affect behavior. Neuron 53 439–452 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K. A., Hellevuo K., Tabakoff B. (1994). The 5-HT3 antagonist MDL-72222 exacerbates ethanol withdrawal seizures in mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 18 410–414 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. A., Roth B. L. (2001). Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT(2A) receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain Res. Bull. 56 441–451 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00623-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A. R., Johnson P., Mountford J. A., Nimgaonkar V. L. (1985). Some anticonvulsant drugs alter monoamine-mediated behaviour in mice in ways similar to electroconvulsive shock; implications for antidepressant therapy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 84 337–346 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb12918.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harandi M., Aguera M., Gamrani H., Didier M., Maitre M., Calas A., et al. (1987). gamma-Aminobutyric acid and 5-hydroxytryptamine interrelationship in the rat nucleus raphe dorsalis: combination of radioautographic and immunocytochemical techniques at light and electron microscopy levels. Neuroscience 21 237–251 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90336-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden C. L. (2002). The co-morbidity of depression and epilepsy: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment. Neurology 59 S48–S55 10.1212/WNL.59.6_suppl_4.S48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelwood L. A., Sanders-Bush E. (2004). His452Tyr polymorphism in the human 5-HT2A receptor destabilizes the signaling conformation. Mol. Pharmacol. 66 1293–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges D., Jeppson K., Whitehead P. (2003). Antipsychotic medication and seizures: a review. Drugs Today (Barc.) 39 551–557 10.1358/dot.2003.39.7.799445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick-Davis K., Grinde E., Harrigan T. J., Mazurkiewicz J. E. (2005). Inhibition of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine2c receptor function through heterodimerization: receptor dimers bind two molecules of ligand and one G-protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280 40144–40151 10.1074/jbc.M507396200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer D. C., Hauser W. A., Olafsson E., Ludvigsson P., Kjartansson O. (2006). Depression and suicide attempt as risk factors for incident unprovoked seizures. Ann. Neurol. 59 35–41 10.1002/ana.20685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka N., Suemaru K., Araki H. (2010). Serotonin-dopamine antagonism ameliorates impairments of spontaneous alternation and locomotor hyperactivity induced by repeated electroconvulsive seizures in rats. Epilepsy Res. 90 221–227 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka N., Suemaru K., Takechi K., Li B., Araki H. (2011). Inhibitory effects of valproate on impairment of Y-maze alternation behavior induced by repeated electroconvulsive seizures and c-Fos protein levels in rat brains. Acta Med. Okayama 65 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins G. A., Sellers E. M., Fletcher P. J. (2013). From obesity to substance abuse: therapeutic opportunities for 5-HT2C receptor agonists. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 560–570 10.1016/j.tips.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose S., Ashby C. R., Jr. (2002). An open pilot study combining risperidone and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor as initial antidepressant therapy. J. Clin. Psychiatry 63 733–736 10.4088/JCP.v63n0812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell L. L., Cunningham K. A. (2015). Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacol. Rev. 67 176–197 10.1124/pr.114.009514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdina P. D., Bakish D., Chudzik J., Ravindran A., Lapierre Y. D. (1995). Serotonergic markers in platelets of patients with major depression: upregulation of 5-HT2 receptors. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 20 11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdina P. D., Bakish D., Ravindran A., Chudzik J., Cavazzoni P., Lapierre Y. D. (1997). Platelet serotonergic indices in major depression: up-regulation of 5-HT2A receptors unchanged by antidepressant treatment. Psychiatry Res 66 73–85 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)03046-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdina P. D., Demeter E., Vu T. B., Sotonyi P., Palkovits M. (1993). 5-HT uptake sites and 5-HT2 receptors in brain of antidepressant-free suicide victims/depressives: increase in 5-HT2 sites in cortex and amygdala. Brain Res. 614 37–44 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91015-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. Y., Lee H. W., Chen S. D., Shaw F. Z. (2012). Lamotrigine ameliorates seizures and psychiatric comorbidity in a rat model of spontaneous absence epilepsy. Epilepsia 53 2005–2014 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illi A., Setala-Soikkeli E., Viikki M., Poutanen O., Huhtala H., Mononen N., et al. (2009). 5-HTR1A, 5-HTR2A, 5-HTR6 TPH1 and TPH2 polymorphisms and major depression. Neuroreport 20 1125–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac M. (2005). Serotonergic 5-HT2C receptors as a potential therapeutic target for the design antiepileptic drugs. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 5 59–67 10.2174/1568026053386980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakus R., Bagdy G. (2011). “The Role of 5-HT2C Receptor in Epilepsy. In: 5-HT2C Receptors in the Pathophysiology of CNS Disease,” in 5-HT2C Receptors in the Pathophysiology of CNS Disease, eds Di Giovanni G., Esposito E., Di Matteo V. (Wien: Springer-Verlag; ), 429–444. [Google Scholar]