Abstract

Transcriptomes of many species are proving to be exquisitely diverse, and many investigators are now using high-throughput sequencing to quantify non-protein-coding RNAs, namely small RNAs (sRNA). Unfortunately, most studies are focused solely on microRNA changes, and many investigators are not analyzing the full compendium of sRNA species present in their large datasets. We provide here a rationale to include all types of sRNAs in sRNA sequencing analyses, which will aid in the discovery of their biological functions and physiological relevance.

Keywords: small RNA, RNA sequencing, long-noncoding RNA, transcriptome, microRNA, high-throughput sequencing, data analysis

The emergence of transcriptomic analyses

J. Craig Venter’s human expressed sequence tag (EST) database, published in 1991, is considered to be the first human gene expression profiling study and was completed using automated Sanger sequencing methods, a significant advance at the time [1]. By 1995, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) was the state-of-the-art method for profiling gene (mRNA) expression; however, hybridization microarrays quickly became the popular choice and remained so until very recently [2]. It was during this time (mid-1990s) that the term ‘transcriptome’ first appeared, the first of many -omics, derived from the term genomics, that are now popular across science. After a decade of microarrays, sequencing-by-synthesis emerged and set forth the rapid development of DNAseq and RNAseq approaches, which coincided with the availability of short-read massive parallel sequencing platforms, later known as next-generation sequencing (NGS) [3]. Currently, many investigators are using RNAseq approaches to quantify long (e.g., mRNA) or sRNA expression; however, owing to specific barriers they are not fully analyzing the large amount of information provided by these approaches.

miRNA analysis

The study of non-coding sRNAs, particularly miRNAs (19–22 nt), has gained significant attention in recent years as 40% (12 971/32 879) of all miRNA publications in Pubmed have been published during the past 18 months (2013 through June 2014). Currently, there are over 35 000 annotated mature miRNAs in 223 species cataloged in miRBase (v21; http://mirbase.org), >2500 of which are human. Nonetheless, miRNAs are highly abundant and dominant in many non-mammalian species, and researchers from wide-fields of study are investigating miRNAs in yeast, worms, flies, plants, and many other species. Although there are multiple strategies to profile miRNAs, the current state of the art is sRNA-seq, and many investigators are now using this approach on a wide-variety of tissues and fluids. sRNAseq is a class of methods used to perform high-throughput sRNA sequencing on libraries of sRNAs ligated to terminal adapters for reverse transcription and amplification. Although miRNAs are only one of the many sRNA species in sRNAseq datasets, miRNAs remain the most popular class to study, largely because they can arise from autonomous transcriptional units, their processing steps are relatively understood, and the general mechanism for their biological functions is known. Unfortunately, many investigators neglect the copious amounts of non-miRNA sRNA species present in their datasets. A common barrier is often the lack of genomic annotations in alignment tools for non-miRNA species. Many investigators are unsure how to place altered expression values of non-miRNA sRNA species into biological contexts because their biological functions and physiological relevance are largely unknown. Moreover, many of these new sRNAs are not as widely conserved across many species as miRNAs.

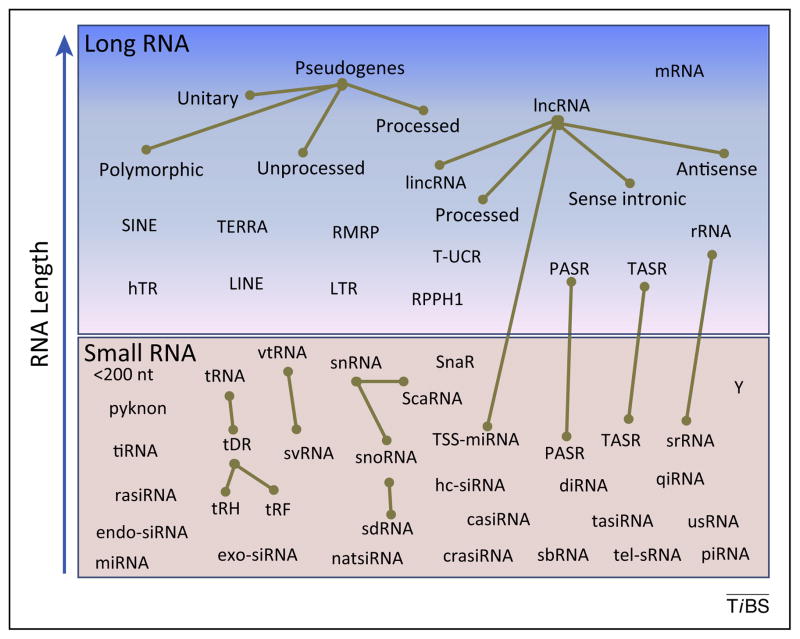

Nevertheless, some groups are striving to resolve the functional impact of non-miRNA sRNAs, and there has been an explosion of novel sRNA species reported in literature. Recent advances in library preparation and NGS technologies enable platforms to now generate hundreds of gigabases per run, which allows for tremendous depth of sequencing into the sRNA transcriptome. This has facilitated the identification of many low-abundance species. Most interestingly, a wide-range of sRNA fragments derived from long RNA species has emerged (Figure 1, Table 1) [4]. These sRNAs are not likely to be the result of random degradation because their consistent alignments, specific terminal ends (evidence of RNase III cleavage), high read counts, and sequence characteristics suggest they are instead regulated cleavage products; however, there is bias in different RNAseq approaches, and protective RNA binding proteins may produce specific reads during normal RNA degradation and turnover [5]. Although we know very little about many of these novel sRNAs, they have great potential to regulate gene expression and biological processes similarly to miRNAs. As such, there is a great need to study these sRNAs and the protein binding factors that mediate their biological functions.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the diversity of long and small RNAs. The gold edge represents small RNAs (sRNA) derived from long parent RNA; sRNAs are RNAs ≤200 nt in length whereas long RNA are significantly bigger. (Long RNAs) hTR, human telomerase RNA; lincRNA, large intergenic non-coding RNA; LINE, long interspersed element; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LTR, long terminal repeat; mRNA; PASR, promoter-associated long RNA; RMPR, RNA component of mitochondrial RNA processing endoribonuclease RPPH1, ribonuclease P RNA component H1; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; SINE, short interspersed element; TASR, termini-associated sRNA; TERRA, telomeric repeat-containing RNA; T-UCR, transcribed ultraconserved region. (Small RNAs) casiRNA, cis-acting siRNA; crasiRNA, centromere repeat-associated sRNA; diRNA, double-strand break-induced sRNA; endo-siRNA, endogenous small interfering RNA; exo-siRNA, exogeneous small interfering RNA; hc-siRNA, heterochromatic small interfering RNA; miRNA, microRNA; natsiRNA, natural antisense siRNA; piRNA, Piwi-interacting RNA; qiRNA, QDE-2-interacting sRNA; rasiRNA, repeat-associated siRNA; ScaRNA, small Cajal-body RNA; sbRNA, stem-bulge RNA; sdRNA, snoRNA-derived small RNA; SNAR, small NF90-associated RNA; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; srRNA, sRNAs-derived from rRNA; svRNA, small vault RNA; tasiRNA, trans-acting siRNA; tDR, tRNA-derived sRNA; tel-sRNA, telomere-specific sRNA; tiRNA, transcription initiation sRNA; tRH, tRNA-derived halves; tRF, tRNA-derived fragments; TSS-miRNA, transcriptional start-site-microRNA; usRNA, unusually small RNA; vtRNA, vault RNA; Y, Y RNA.

Table 1.

sRNAs derived from long parent non-coding RNAsa

| Abbreviation | Name | Class | Size (nt) | Function | Database (website) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | microRNA | miRNA | 19–22 | Post-transcriptional gene repression | miRBase.org |

| TSS-miRNA | Transcriptional start-site-miRNA | miRNA | 20–30 | Post-transcriptional gene regulation | N/A |

| moRNA | miRNA-offset RNAs | miRNA | 19–22 | N/A | N/A |

| usRNA | Unusually small RNA | miRNA | 15–17 | Post-transcriptional gene regulation | N/A |

| endo-siRNA | Endogenous small interfering RNA | siRNA | 21 | Somatic inhibitor of retrotransposition, post-transcriptional gene repression | N/A |

| exo-siRNA | Exogeneous small interfering RNA | siRNA | 21 | Gene-targeted silencing, anti-viral | N/A |

| natsiRNA | Natural antisense siRNA | siRNA | 21–24 | Pathogen resistence, post-transcriptional gene regulation | bis.zju.edu.cn/pnatdb |

| casiRNA | Cis-acting siRNA | siRNA | 24 | Transposon methylation, chromatin modification | N/A |

| tasiRNA | Trans-acting siRNA | siRNA | 21 | Post-transcriptional gene repression | bioinfo.jit.edu.cn |

| rasiRNA | Repeat-associated siRNA | siRNA | 26–31 | Transposon methylation, chromatin modification | deepbase.sysu.edu.cn |

| hc-siRNA | Heterochromatic small interfering RNA | siRNA | 24 | Genome maintenance, DNA methylation | N/A |

| 3′ U tRF | tRNA-derived fragment | tDR | 20 | Post-transcriptional gene repression | genome.ucsc.edu |

| 5′ tRF | tRNA-derived fragment | tDR | 20 | Post-transcriptional gene repression, translational repression | genome.ucsc.edu |

| 3′CCA tRF | tRNA-derived fragment | tDR | 23 | Post-transcriptional gene repression, RNA metabolism | genome.ucsc.edu |

| tRH | tRNA-derived half | tDR | 30–35 | Protein synthesis repression, post-transcriptional gene repression | genome.ucsc.edu |

| piRNA | Piwi-interacting RNA | piRNA | 25–33 | Germline post-transcription gene repression, transposon regulation, chromatin modification | pirnabank.ibab.ac.in |

| crasiRNA | Centromere repeat-associated small RNA | chRNA | 34–42 | Cell cycle, centromere formation | N/A |

| tel-sRNAs | Telomere-specific small RNA | chrRNA | 24 | Epigenetic regulation | N/A |

| PASR | Promoter-associated small RNA | CAsRNA | 20–200 | Transcriptional regulation of mRNAs, epigenetic regulation | deepbase.sysu.edu.cn |

| tiRNA | Transcription initiation smRNA | CAsRNA | 18 | Transcriptional regulation of mRNAs, epigenetic regulation | N/A |

| TSSaRNA | Transcription start site-associated RNAs | CAsRNA | 20–90 | Transcriptional regulation of mRNAs, epigenetic regulation | N/A |

| spliRNA | Splice site-associated small RNA | CAsRNA | 17–18 | N/A | N/A |

| H/ACA sdRNA | H/ACA snoRNA-derived RNA | snRNA | 20–24 | Post-transcriptional gene repression, alternative splicing | ensembl.org |

| C/D sdRNA | C/D snoRNA-derived RNA | snRNA | 17–19, 30 | Post-transcriptional gene repression, alternative splicing | ensembl.org |

| svRNA | Small vault RNAs | vRNA | 22–37 | Post-transcriptional gene repression | ensembl.org |

| srRNA | smRNAs-derived from rRNA | rRNA | 24 | Post-transcriptional gene regulation | ensembl.org |

| yDR | Y RNA-derived small RNAs | Y RNA | 24–25, 30 | N/A | ensembl.org |

| sbRNA | Stem-bulge RNA | Y RNA | 67–133 | RNA quality control, chromosomal replication | N/A |

| diRNA | Double-strand break-induced small RNAs | DSB | 21 | DNA double-strand break repair | N/A |

| qiRNA | QDE-2-interacting small RNAs | DSB | 20–21 | DNA double-strand break repair, protein translation | N/A |

Abbreviations: CAsRNA, chromatin-associated sRNA; DSB, DNA double-strand break repair; miRNA, microRNA; N/A, not available; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; tDR, tRNA-derived sRNA; tRF, tRNA-derived sRNA fragment.

miRNAs are only the tip of the iceberg: sRNA diversity

Many sRNAs are named to recognize the parent RNA species from which they were derived. For example, one emerging class that is gaining great interest, the tRNA-derived sRNAs (tDRs), comprise at least four subtypes. tRNA-derived sRNA fragments (tRFs, approximately 20 nt) and tRNA-derived halves (tRHs, approximately 33 nt) are two distinct subclasses with likely different biological functions. Although the physiological roles of tRFs and tRHs are only beginning to be defined, it is clear that they respond to cell stress and their regulatory cleaving enzymes have been elucidated. One subclass of tRFs (3′CCA tRFs) have been reported to act like miRNAs and silence complementary targets [6]. tRHs are generated by angiogenin-mediated cleavage near the anticodon loop in response to starvation, oxidative stress, or other forms of cellular stress. Through a variety of mechanisms, tRHs suppress protein translation [7]. tRHs have also been reported to bind to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4γ (eIF4G) through a distinct sequence motif on the tRH 5′-terminal end and titrate eIF4G away from the pre-initiation complex [7]. Although the exact mechanisms of 5′ tRH suppression of translation are still emerging, it has been shown that, at least for reporter constructs, they inhibit translation independently of seed-sequence complementarity [8]. tDRs have been reported in multiple cell types and diseases. tRHs are also highly abundant in plasma, where they are found associated with protein complexes, for example, high-density lipoproteins (HDL), but are largely excluded from exosomes [9]. Owing to their robust responses to a wide variety of stresses and their potential value as extracellular RNA biomarkers, the study of tDRs is a rapidly growing area of research. Some sRNAs are processed from long non-coding RNAs, including some interesting species derived from pseudogenes, miscellaneous transcripts, and even coding mRNAs (Table 1, Figure 1). Other sRNAs are processed from various parent transcripts (Table 1), including promoter-associated sRNAs (PASR), transcription initiation sRNAs (tiRNAs), unusually small sRNAs (usRNA), TSS-miRNAs, sno-derived RNA (sdRNA), small vault RNAs (svRNA), and sRNAs-derived from rRNA (srRNA) [10,11]. Other examples of non-coding smRNAs which may be present in a sRNAseq datasets. depending on eukaryotic phylogeny or cell type, include endo-siRNAs, exo-siRNAs, double-stranded RNAs (dsRNA), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNA), natural antisense siRNAs (natsiRNA), cis-acting siRNAs (casiRNA), trans-acting siRNAs (tasiRNA), repeat-associated siRNAs (rasiRNA), centromere repeat-associated sRNAs (crasiRNA), and telomere-specific sRNAs (tel-sRNAs) [12]. Many of these sRNAs have been reported to associate with argonaute-RNA-induced silencing complexes [AGO(1-4)-RISC], and thus probably post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression through partial complementary binding to target mRNAs [13]. sRNAseq datasets may also contain reads representing Y RNAs, double-strand break-induced sRNAs (diRNA), stem bulge RNAs (sbRNA), and endo-siRNA-like sRNAs induced by DNA damage and originating from ribosomal (r)DNA regions (QDE-2-interacting sRNAs, qiRNA) (Table 1) [14]. Moreover, many other novel sRNA species probably remain to be discovered. This is particularly evident because many reads in sRNA datasets do align to the human genome, but to unannotated loci. Although this highlights the problem with incomplete genomic annotations and databases, it also alludes to potential discovery in these datasets. To identify and count sRNAs, investigators can use annotated genomic coordinates to align and count reads, or use a non-genome mapping strategy and simply align reads to canonical long and small RNA sequences [15]. Nevertheless, the crucial barrier tostudying non-miRNA sRNAs is the general lack of proper annotations and genomic coordinates (sequence information) for non-coding RNA. Likewise, the field is lacking well-maintained and easily accessible databases for non-miRNA sRNAs. For example, tDR annotations have been problematic for various reasons, including mapping to multiple loci and the organization of tDRs into classes and families. To advance the field, a significant effort is required to further develop and curate sRNA databases to be freely distributed. Nonetheless, a few databases are useful, including the Table Browser from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site (http://www.geno-me.ucsc.edu) and Ensemble (http://www.ensembl.org) gtf annotation files. Although improvements are warranted, there is currently enough available information to begin aligning and counting many types of non-miRNA sRNA reads. In addition to database development, enhanced methods to prepare RNA for sequencing are also needed. For example, Dicer cleavage of double-stranded RNA produces specific terminal chemistry (3′-OH) and currently available library construction kits are designed as such. This presents a problem in species where the most abundant sRNAs are not Dicer products. Therefore, the development of new protocols to address this issue is also encouraged.

Concluding remarks

We are now in a golden era of genomics where the barrier to performing genome-scale high-throughput sequencing is not in the generation of data, but in data analysis and storage. Although the field of genomics is certainly aware of the mining of novel sRNAs, many investigators may not fully appreciate the depth and diversity of sRNAs. We hope that this article will provide motivation for researchers to include more sRNA classes in their analyses and prompt them to develop greater bioinformatic support for analyzing these data. In summary, there are many complexities to be discovered in the deep sRNA transcriptome outside of miRNAs, and it will be up to future studies to separate random cellular products from biologically relevant sRNAs [16]. To achieve this goal, investigators are persuaded to analyze non-miRNA sRNAs in their datasets and help to develop associated tools and databases.

Acknowledgments

K.C.V. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants K22HL113039, DK20593, PO1HL116263; AHA CSA20660001; and a Lupus Research Institute (LRI) Novel Grant award.

References

- 1.Adams MD, et al. Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project. Science. 1991;252:1651–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2047873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schena M, et al. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mortazavi A, et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawaji H, et al. Hidden layers of human small RNAs. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raabe CA, et al. Biases in small RNA deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1414–1426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haussecker D, et al. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA. 2010;16:673–695. doi: 10.1261/rna.2000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanov P, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Small RNAs derived from the 5′ end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. RNA Biol. 2013;10:553–563. doi: 10.4161/rna.24285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhahbi JM, et al. 5′ tRNA halves are present as abundant complexes in serum, concentrated in blood cells, and modulated by aging and calorie restriction. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:298. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sana J, et al. Novel classes of non-coding RNAs and cancer. J Transl Med. 2012;10:103. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, et al. Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6787–6799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman EJ, Carrington JC. Specialization and evolution of endogenous small RNA pathways. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:884–896. doi: 10.1038/nrg2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burroughs AM, et al. Deep-sequencing of human argonaute-associated small RNAs provides insight into miRNA sorting and reveals argonaute association with RNA fragments of diverse origin. RNA Biol. 2011;8:158–177. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, et al. The complex exogenous RNA spectra in human plasma: an interface with human gut biota? PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brosius J. Waste not, want not – transcript excess in multicellular eukaryotes. Trends Genet. 2005;21:287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]