Abstract

G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a large family of proteins that coordinate extracellular signals to produce physiologic outcomes. Adenosine receptors (AR) are one class of GPCRs that have been shown to regulate functions as diverse as inflammation, blood flow, and cellular differentiation. Adenosine signals through four GPCRs that either inhibit (A1AR and A3AR) or activate (A2aAR and A2bAR) adenylyl cyclase. This review will focus on the role of GPCRs, and in particular, adenosine receptors, in adipogenesis. Preadipocytes differentiate to mature adipocytes as the adipose tissue expands to compensate for the consumption of excess nutrients. These newly generated adipocytes contribute to maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Understanding the key drivers of this differentiation process can aid the development of therapeutics to combat the growing obesity epidemic and associated metabolic consequences. Although much literature has covered the transcriptional events that culminate in the formation of an adipocyte, less focus has been on receptor-mediated extracellular signals that direct this process. This review will highlight GPCRs and their downstream messengers as significant players controlling adipocyte differentiation.

More than 30% of adults in the United States are obese (Flegal et al., 2010). This figure is particularly troubling given the medical sequelae of obesity, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, stroke and type II diabetes mellitus (Malnick and Knobler, 2006; Orpana et al., 2010). The need to understand the underlying molecular causes of increased adiposity are increasingly important. Knowledge of these processes will give us enhanced ability to prevent and treat obesity. An increase in body weight occurs when there is an excess of energy intake relative to energy output. While mild obesity is mainly a result of an enlargement in adipocyte size, more severe obesity involves an increase in the number of adipocytes through the differentiation of preadipocytes that reside within the fat pad (Rosen and MacDougald, 2006). Recruitment of preadipocytes and their differentiation to mature cells is important for normal adipose tissue growth, remodeling and healthy expansion that is thought to help prevent the deleterious metabolic consequences of obesity. Much is known about the intracellular sequence of events that results in the differentiation of adipocytes, however, there has been less focus on the extracellular physiologic signals that regulate adipogenesis.

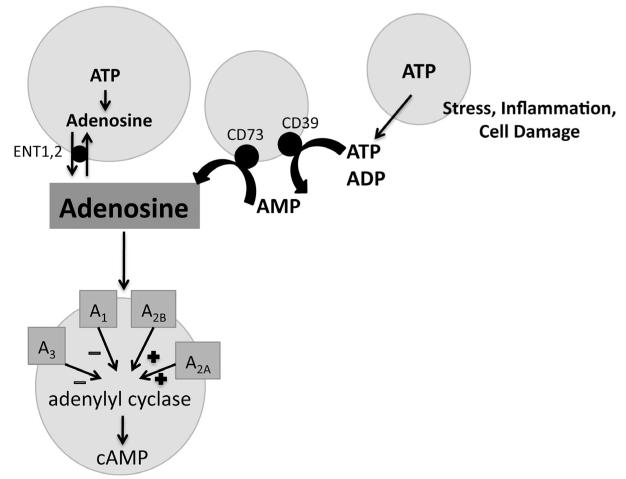

Nucleotides and their metabolites, like ATP and adenosine, signal to neighboring cells to regulate cellular processes such as tissue damage and repair and may play a role in cellular differentiation (Bours et al., 2006). ATP and adenosine are released from damaged cells during hypoxia, ischemia and inflammation (Linden, 2001; Chen et al., 2006; Fredholm, 2007; Eltzschig and Carmeliet, 2011). Extracellular ATP activates purinergic receptors or can be broken down to adenosine by ectoNTPDase, CD39, and ecto-5′-nucleotidase, CD73 (Zimmermann, 2000; Yegutkin, 2008). Adenosine acts on four adenosine receptors, a conserved group of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are defined by their ability to inhibit (A1AR and A3AR) or stimulate (A2aAR and A2bAR) adenylyl cyclase (Jacobson and Gao, 2006; Fig. 1). Purinergic signaling is an important regulator of stem cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation (reviewed in Glaser et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

Adenosine production and signaling. Adenosine and ATP are released from cells during times of stress, inflammation, and cell damage. ATP can be converted to adenosine by CD39 and CD73 ectonucleotidases. Adenosine can also be released from cells by transporters, ENT1,2. Adenosine binds to receptors on the cell membrane that inhibit (A1AR and A3AR) or stimulate (A2aAR and A2bAR) adenylyl cyclase.

This review will focus on the role of adenosine receptors and downstream signaling effectors in adipogenesis. We will begin with an overview of adipogenesis and the model systems used to study the process. We will review relevant literature linking G-protein coupled receptors, and more specifically adenosine receptors to adipocyte differentiation, and discuss the effect of two downstream effectors, cyclic AMP (cAMP) and calcium (Ca2+), on adipocyte differentiation.

Adipogenesis in the Context of Adipose Tissue Remodeling

During the development of obesity, the adipose tissue expands by hypertrophy and by hyperplasia to accommodate excess nutrients (Rosen and MacDougald, 2006). It has been suggested that type II diabetes is a consequence of the inability of adipocytes to differentiate (Danforth, 2000; Jansson et al., 2003; Spalding et al., 2008). Adipogenesis occurs in response to excess nutrients in order to maintain metabolic homeostasis. The addition of adipocytes allows the organism to store more nutrients in the adipose tissue and prevents the pathologic accumulation of lipid in other organs like the liver, muscle, and heart. This redistribution of fat, or lipodystrophy, can lead to the development of type II diabetes. It is known that insulin sensitizers, like thiazolidinediones (TZDs), enhance de novo adipogenesis and hence increase adipose tissue storage capacity (Okuno et al., 1998; Chao et al., 2000). Furthermore, adipose tissue implantation into a diabetic lipodystrophic mouse model has been demonstrated to improve glucose tolerance (Gavrilova et al., 2000). The recruitment of new adipocytes improves insulin sensitivity as a result of an increase in storage capacity, but also due to an increase in insulin signaling by the newly generated adipocyte. Small, newly formed adipocytes are more insulin sensitive than their hypertrophied counterparts (Abbott and Foley, 1987; Tan and Vidal-Puig, 2008; Arner et al., 2010; Virtue and Vidal-Puig, 2010). Furthermore, large adipocytes have been associated with reduced insulin sensitivity and development of type II diabetes in humans (Weyer et al., 2000; Lundgren et al., 2007; Arner et al., 2010). Given the importance of adipocyte turnover and recruitment in the pathophysiology of diabetes, understanding the control of adipocyte differentiation is clearly important.

Overview of Adipogenesis and Model Systems to Study this Process in Culture and In Vivo

Adipogenesis in culture

Adipogenesis has been extensively studied in vitro. The most frequently used preadipocye cell lines are the 3T3-F442A and 3T3-L1 cells, which were isolated from the Swiss 3T3 cell line (Green and Meuth, 1974; Green and Kehinde, 1976). Another less commonly used cell line, Ob17 cells are derived from adipose precursors that were isolated from the epidiymal fat pads of ob/ob adult mice (Negrel et al., 1978). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which can differentiate to several lineages including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes are commonly used primary cells for the study of adipogenesis, and can be isolated from the bone marrow and from umbilical cord blood (Caplan, 1991; Horwitz et al., 2005). Other primary cells that can be induced to differentiate to adipocytes in culture include mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and preadipocytes found in the stromal-vascular fraction of mouse and human adipose tissue. To promote in vitro adipocyte differentiation, cells are grown to confluence and growth arrest. The addition of a cocktail of adipocyte-promoting factors causes the cells to re-enter the cell cycle and undergo several rounds of mitosis, known as mitotic clonal expansion (MCE), which appears to be a requirement for terminal adipocyte differentiation, at least in vitro (Otto and Lane, 2005). The cells enter a second, permanent period of growth arrest following the expression of certain key adipogenic factors (Umek et al., 1991; Altiok et al., 1997; Morrison and Farmer, 1999).

A defined set of transcription factors, including the ccaat enhancer binding proteins (C/EBP) family and peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) have been shown to be instrumental for adipogenesis in all model systems studied (Tontonoz et al., 1994; Barak et al., 1999; Rosen et al., 1999; Wu et al., 1999; Koutnikova et al., 2003). Early in differentiation, C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are transiently induced (Cao et al., 1991; Yeh et al., 1995; Darlington et al., 1998). The C/EBP family are basic-leucine zipper transcription factors, which act as hetero- or homodimers (Lekstrom-Himes and Xanthopoulos, 1998). Ectopic expression of C/EBPβ is sufficient to induce differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, while ectopic C/EBPδ expression only accelerates differentiation (Yeh et al., 1995). C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ expression promotes the expression of PPARγ, likely via C/EBP binding sites in the PPARγ promoter (Zhu et al., 1995; Fajas et al., 1997). PPARγ induces the expression of C/EBPα. C/EBPα overexpression in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes induces fat differentiation, while C/EBPα antisense RNA blocks differentiation (Lin and Lane, 1992; Freytag et al., 1994; Lin and Lane, 1994). PPARγ and C/EBPα then promote the expression of genes necessary for adipocyte function, including glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, fatty acid synthase (FAS), acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC), glucose transporter type 4 (Glut4), insulin receptor, and fatty acid binding protein (FABP/aP2), and the accumulation of triglycerides (Spiegelman et al., 1993; Tontonoz et al., 1995a,b; Kubota et al., 1999; Rosen et al., 1999). PPARγ has been described as the “master regulator” of adipocyte differentiation because the expression of PPARγ is both necessary and sufficient for adipocyte differentiation (Tontonoz et al., 1994; Rosen et al., 1999). Accordingly, the differentiation of preadipocyte cell lines is achieved with the use of various inducers, including insulin, glucocorticoids, methylisobutyl-xanthine (MIX) and TZDs (PPARγ agonists). Insulin increases the percentage of differentiated cells and the amount of lipid accumulation (Girard et al., 1994). It is believed that the effect of insulin on differentiation occurs through cross-activation of the insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor, as there are few insulin receptors on preadipocytes. The glucocorticoid, dexamethasone induces C/EBPδ expression and reduces the expression of preadipocyte factor-1 (pref-1), a negative regulator of adipogenesis (Wu et al., 1996; Smas et al., 1999). MIX, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, enhances differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, reportedly by increasing levels of adipocyte-promoting transcription factors (Cao et al., 1991).

Adipogenesis studied in vivo

Several studies have employed in vivo models to study the control of adipogenesis. It was reported that chimeric mice derived from ES cells with wild type PPARγ and cells with a homozygous deletion of PPARγ had no PPARγ null cells in the white adipose tissue (Rosen et al., 1999). Furthermore, heterozygous deletion of PPARγ leads to animals resistant to diet-induced obesity (Kubota et al., 1999). Homozygous deletion of C/EBPα results in decreased accumulation of fat in white and brown adipose tissue (Wang et al., 1995). On the other hand, C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are not necessary for adipocyte differentiation, as double knockout mice develop adipose tissue (albeit reduced compared to wild type mice) and express PPARγ and C/EBPα (Tanaka et al., 1997). This suggests the existence of adipogenic transcriptional cascades that do not involve C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ. Adipocyte determination and differentiation-dependent factor 1/sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (ADD1/SREBP1), which was independently cloned as a factor from fat cells and as a liver protein that bound sterol-regulatory-elements in cholesterol regulatory genes, may be responsible for one of these pathways (Tontonoz et al., 1993; Brown and Goldstein, 1997). ADD/SREBP1 is induced during adipogenesis and increased by refeeding in mice, most likely due to increased insulin signaling (Kim and Spiegelman, 1996; Kim et al., 1998). Ectopic expression of SREBP1 in 3T3-L1 cells induces fat cell differentiation, while a dominant negative form of SREBP1 blocks differentiation in these same cells (Kim and Spiegelman, 1996; Fajas et al., 1999).

Recent research efforts have also focused on identifying and defining adipose precursors in vivo. Several attempts have been made to clarify the source of adipocytes (reviewed in Park et al., 2008 and Zeve et al., 2009). One group performed lineage tracing analysis using a PPARγ reporter mouse and found that the progenitors resided in the adipose tissue vasculature, are present as early as post-natal day 1 (P1), and proliferate between P10 and P35 (as evidenced by BrdU staining; Tang et al., 2008). A second group identified progenitors within the adipose tissue and defined the cells by the presence of cell surface markers (lin−: CD29+:CD34+:Sca-1+:CD24+) and showed that they were capable of generating an adipose tissue depot in a lipodystrophic mouse model (Rodeheffer et al., 2008) and differentiating in response to high fat diet (Birsoy et al., 2008). More recently, the zinc finger protein, Zfp423 was shown to play a role in preadipocyte determination (Gupta et al., 2010). The group that identified this factor generated a mouse model in which Zfp423 drives GFP expression (Gupta et al., 2012). This mouse model will provide an excellent tool to facilitate the isolation and study of a more purified population of preadipocytes from adipose tissue.

G-Protein Coupled Receptors and Accessory Proteins and Adipogenesis

The P2Y purinergic receptors are a class of G-protein coupled receptors that may play a role in adipogenesis (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Abbracchio et al., 2006; Burnstock, 2007). Upon binding P2Y receptors, ATP enhances the effect of adipogenic hormones on the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells by altering the organization of actin filaments and promoting conversion to a lipid-laden cell (Omatsu-Kanbe et al., 2006). ATP also inhibits the proliferation and stimulates the migration of MSCs (Ferrari et al., 2011). Acting through P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors, ATP was also shown to increase adipogenesis of human bone marrow-derived MSCs by promoting lipid accumulation and the expression of PPARγ (Ciciarello et al., 2013).

Short chain fatty acids acetate and propionate are ligands for G-protein coupled receptor 43 (GPCR43), while medium and long chain free fatty acids are ligands for G-protein receptor 120 (GPR120) (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Hong et al., 2005). GPCR43 couples to Gαi and GPR120 couples to Gαq (Brown et al., 2003; Hirasawa et al., 2005). GPCR43 and GPR120 expression is high in mouse adipose tissue and in isolated adipocytes but not in preadipocytes in the stromal-vascular fraction (Hong et al., 2005; Gotoh et al., 2007). Adipose tissue GPCR43 and GPR120 is upregulated in mice fed high fat diet as compared to standard diet and GPCR43 and GPR120 expression increases during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells (Hong et al., 2005; Gotoh et al., 2007). Knockdown of GPCR43 or GPR120 expression by siRNA decreases adipocyte differentiation (Hong et al., 2005; Gotoh et al., 2007). GPR120 KO mice on a high fat diet have increased weight gain, glucose intolerance, and hepatic lipid deposition as well as decreased adipocyte differentiation (Ichimura et al., 2012). Moreover, GPR120 expression in human adipose tissue is greater in obese individuals as compared to lean individuals and a loss of function mutation in GPR120 is associated with an increased risk of obesity in a European population (Ichimura et al., 2012). However, there is no relationship between GPCR43 and adipogenic potential of preadipocytes isolated from human omental adipose tissue (Dewulf et al., 2013).

G-protein receptor 103 (GPR103) is a receptor whose ligand is QRFP, an orexigenic neuropeptide made up of 43 amino acids residues, and couples to Gαq to enhance intracellular Ca2+ levels (Fukusumi et al., 2003; Jiang et al., 2003; Takayasu et al., 2006). Although predominantly expressed in the nuclei of the hypothalamus, one subtype of the receptor, GPR103b, is found in multiple tissues including adipose tissue and similarly QRFP peptides are mostly produced in the brain but are also found in adipose tissue (Fukusumi et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). QRFP is a member of the RFamide family of peptides which all contain carboxy-terminal arginine (R) and amidated phenylalanine (F) residues (Price and Greenberg, 1977). The RFamide family has been associated with regulation of adipocyte differentiation (Fuku-sumi et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). The expression of GPR103b increases with differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells (Mulumba et al., 2010). QRFP peptides increase adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells (Mulumba et al., 2010). Moreover, the expression of GPR103b increases in the epididymal adipose tissue and isolated epididymal adipocytes of mice fed a high fat diet as compared to normal diet (Mulumba et al., 2010).

β-Adrenergic receptors are coupled to Gαs proteins. The expression of β2 adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) and β3-AR increases during the differentiation of mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs (Li et al., 2010). The β-agonist, isoproterenol, inhibits adipocyte differentiation by activating β2-ARs and β3-ARs but not β1-ARs (Li et al., 2010). Furthermore, the inhibitory action of the β-adrenergic receptors is due to activation of PKA (Li et al., 2010). The thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor is another G-protein coupled receptor whose ligand is a hormone and couples to Gαs. Transfection of a constitutively active TSH receptor leads to a decrease in adipogenesis (Zhang et al., 2009). However, adipogenesis was also shown to be enhanced by TSH in cultured embryonic stem cells (Lu and Lin, 2008).

G-Protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) reduce GPCR signaling by phosphorylating serine/threonine residues of G-protein-coupled receptors and promoting the binding of arrestins and subsequent receptor internalization (Kohout and Lefkowitz, 2003; Lefkowitz, 2007). GRK5 is highly expressed in white adipose tissue (Wang et al., 2012). GRK5 KO mice fed a high fat diet gain less weight and have less adipose tissue mass as compared to control mice despite no differences in feeding or energy expenditure (Wang et al., 2012). GRK5 KO mice have reduced expression of lipogenic and adipogenic genes in WAT as compared to control mice (Wang et al., 2012). Furthermore, MEFs and stromal-vascular cells from GRK5 KO mice have impaired adipogenesis during in vitro adipogenic induction (Wang et al., 2012).

Adenosine Receptors and Adipogenesis

Adenosine is continuously released from fat cells in vitro and subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo (Schwabe et al., 1973; Fredholm, 1976). The release of adenosine is increased by ischemia, catecholamine exposure, or sympathetic nerve stimulation (Fredholm and Sollevi, 1981). The A2bAR and A2aAR are predominantly expressed on preadipocytes, while mature adipocytes mainly express A1AR (Vassaux et al., 1993; Borglum et al., 1996). During adipogenesis the expression of the adenylyl cyclase stimulatory adenosine receptors decreases and the expression of the adenylyl cyclase inhibitory adenosine receptors increases (Ravid and Lowenstein, 1988; Vassaux et al., 1993; Borglum et al., 1996; Gharibi et al., 2011). The A2bAR has been shown to be the functionally dominant adenosine receptor in MSCs, while the A2aAR has been shown to be important for the proliferation and differentiation of murine bone marrow-derived MSCs into adipocytes (Evans et al., 2006; Katebi et al., 2009; Gharibi et al., 2011). In Ob1771 preadipocytes, 5′-N-Ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA), a non-specific adenosine receptor agonist, was shown to increase cAMP, but CGS 21680, an A2aAR specific agonist, did not increase cAMP, suggesting that the A2bAR is the predominant adenosine receptor in preadipocytes (Borglum et al., 1996).

Most published studies on the role of adenosine receptors in adipogenesis have examined the effect of the receptors with pharmacologic agonists and overexpression studies in cell lines. An early study showed that NECA treatment of rat primary preadipocytes increases the number of differentiated cells (Vassaux et al., 1993). A more recent study showed that activation of the A2aAR and A1AR in MSCs enhances adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation. (Gharibi et al., 2011) It was reported that A2aAR expression promoted PPARγ and C/EBP-α expression, while A1AR increased lipogenesis and lipid accumulation, rather than differentiation (Gharibi et al., 2011). The A1AR has also been shown to play a role in other functions of the adipocyte, including blocking lipolysis, promoting leptin secretion, and protecting against insulin resistance (Fredholm, 1978; Cheng et al., 2000; Rice et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2001; Schoelch et al., 2004; Johansson et al., 2007; Szkudelska et al., 2009). Transfection of A1AR into a murine osteoblast precursor cell line, 7F2, or into ob17 cells increased adipocyte marker expression and lipid accumulation (Tatsis-Kotsidis and Erlanger, 1999a,b; Gharibi et al., 2012). Transfection of the A2bAR in these cells also augmented osteoblast mRNA expression and inhibited adipogenesis, even in the presence of adipocyte differentiation media (Gharibi et al., 2012).

The mechanism underlying the effect of the adenosine receptors on adipocyte differentiation has not been elucidated. The adenosine receptors couple to Gαs (A2aAR and A2bAR), Gαi (A1AR and A3AR) and to Gαq (A2bAR) and all the adenosine receptors can activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. We will next explore the role of these signaling pathways on adipogenesis.

cAMP and Adipogenesis

G-protein coupled receptors that are bound to Gαs activate adenylyl cyclase and increase cAMP levels. The role of cAMP in adipogenesis is debated. Early studies suggested that cAMP may promote adipogenesis. MIX, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is often used in vitro to stimulate adipocyte differentiation, most likely by increasing the level of C/EBPβ (Cao et al., 1991). MIX treatment throughout differentiation marginally increased adipocyte differentiation in rat primary preadipocytes cells (Bjorntorp et al., 1980) while MIX or forskolin treatment for the first two days following induction of differentiation increased differentiation in these same cells (Wiederer and Loffler, 1987). Treatment of 3T3-L1 cells with dibutyryl-cAMP (a cAMP analog), forskolin, theophylline, or MIX for 48 h increased adiopogenesis (Brandes et al., 1990; Hauner, 1990; Schmidt et al., 1990). Similarly, a more recent study found that the addition of forskolin (100 μM), MIX, or Sp-cAMP (a cAMP analog) enhanced the adipocyte differentiation of human bone-marrow derived MSCs (Yang et al., 2008). However, other studies have suggested that cAMP does not enhance adipocyte differentiation. For example, neither forskolin, 8-Br-cAMP nor MIX treatment of preadipocytes from porcine adipose tissue enhanced adipogenesis when applied 1-7 days prior to induction (Boone et al., 1999). It appears that the level and timing of cAMP elevation during differentiation may be the most important factor in predicting the effect on adipogenesis. Yarwood et al. found that 3T3-F442A cells treated for 3 days with agents that increase cAMP levels, such as 50 μM forskolin, cholera toxin or CPT-cAMP inhibited adipogenesis. In contrast, MIX promoted adipogenesis in these same cells. The authors then tested various concentration of forskolin on adipocyte differentiation and found that low levels of forskolin (1 nM) enhanced adipogenesis, while higher levels of forskolin (above 1 μM) inhibited differentiation (Yarwood et al., 1995). The timing of cAMP elevation may also change the effect on adipocyte differentiation. For example, one study found that a 2-day treatment of 3T3-L1 cells with the cAMP analog, 8-Br-cAMP, or forskolin could replace MIX in the adipogenic induction cocktail, but 15 min pretreatment with forskolin (1 μM) or 8-Br cAMP significantly reduced adipogenesis in the presence of MIX (Li et al., 2008). The authors also showed that treatment with an adenylate cyclase inhibitor 15 min prior to addition of MIX, dexamethasone, and insulin accelerated adipogenesis as shown by an earlier rise in C/EBPα and PPARγ and enhanced Oil Red O staining (Li et al., 2008). In another study, intermittent forskolin treatment (1 h per day for 6 days) of human bone marrow-dervied MSCs inhibited adipocyte differentiation (Rickard et al., 2006). Taken together, it appears that the effect of cAMP on adipogenesis is likely dependent on the level and duration of cAMP signaling (Yarwood et al., 1995; Rickard et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008). The differing effects of cAMP may also be due to cellular compartmentalization of certain kinases and phosphatases with particular receptors (reviewed in McConnachie et al., 2006; Cheepala et al., 2013).

Cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) has been reported to be necessary and sufficient for adipogenesis in vitro. CREB is constitutively expressed in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts prior to induction of adipogenesis (Reusch et al., 2000). CREB binds cAMP response elements (CREs) and increases transcription of genes important for adiopocyte function, including phosphoenolpyruvate, FABP/aP2 and FAS (Reusch et al., 2000). CREB has also been shown to induce C/EBPβ and cyclin D1, which promotes mitotic clonal expansion, and reduce expression of Wnt10b, an inhibitor of adipogenesis (Zhang et al., 2004; Fox et al., 2008). Ectopic expression of CREB in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts is sufficient to induce adipocyte differentiation, while expression of a dominant negative CREB prevents adipogenesis (Reusch et al., 2000). Knockdown of CREB with siRNA prevents adipocyte differentiation even in cells ectopically expressing C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, or PPARγ (Fox et al., 2006). However, the CREB knock out (KO) mouse shows no obvious adipose phenotype (Rudolph et al., 1998).

On the other hand, the alpha subunit of G protein, Gαs, which activates adenylate cyclase and increases intracellular cAMP levels, has been shown to play an inhibitory role in adipogenesis. The expression of Gαs declines with adipogenesis and constitutive expression of Gαs inhibits adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 and 3T3-F442A cells via a reduction in PPARγ (Wang et al., 1992, 1996; Denis-Henriot et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2009). Conversely, suppression of Gαs expression by antisense oligonucleotides accelerates adipogenesis in the presence or absence of classical inducers (Wang et al., 1992). However, a recent study showed that mice with adipose-specific Gαs deficiency have a significant loss of in vivo adipogenesis, as assessed by an almost complete absence of mesenteric and epididymal fat in the knockout mice and very small inguinal fat pads (Chen et al., 2010). Moreover, embryonic fibroblasts from these null mice differentiate poorly to adipocytes even in the presence of MIX, DEX, insulin, and rosiglitazone (Chen et al., 2010). Cholera toxin, which ADP-ribosylates and activates Gαs, blocks adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, while pertussis toxin, which also increases intracellular levels of cAMP, does not inhibit adipocyte differentiation (Wang et al., 1992). It has, therefore been suggested that the Gαs subunit may play a role in regulating adipogenesis that is independent of activation of adenylyl cyclase and elevating cAMP (Wang et al., 1996; Wang and Malbon, 1999).

Calcium Signaling and Adipogenesis

The adenosine receptors are also known to couple to Gαq and increase cytoplasmic levels of Ca2+. Several studies in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes have demonstrated that high intracellular levels of calcium early in adipogenesis potently inhibit adipogenesis, while increased intracellular calcium in the late stage of adipogenesis promotes differentiation (Miller et al., 1996; Ntambi and Takova, 1996; Shi et al., 2000; Neal and Clipstone, 2002). In one study, the calcium dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, calcineurin was found to be necessary for calcium inhibition of adipogenesis (Neal and Clipstone, 2002). Calcineurin overexpression decreased protein levels of PPARγ and C/EBPα during adipocyte induction as compared to control, but did not affect protein levels of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ (Neal and Clipstone, 2002). Calcineurin inhibition of PPARγ and C/EBPα may be mediated by Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) (Neal and Clipstone, 2002). NFAT is a transcription factor that upon dephosphorylation by calcineurin translocates to the nucleus. NFAT has been shown to bind to the aP2 promoter during fat cell differentiation and cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of calcineurin, inhibits fat cell differentiation (Ho et al., 1998). Prostaglandin F2α binding to its receptor activates Gαq protein and inhibits adipogenesis (Liu and Clipstone, 2007). However, PLCdelta1 KO mice have reduced body weight and reduced epididymal fat mass on regular diet or following high fat diet as compared to controls. Adipocytes were smaller and preadipocytes isolated from subcutaneous tissue from these KO mice had a reduced potential to differentiate into adipocytes (Hirata et al., 2011).

Calcium oscillations are believed to confer sensitivity and specificity to pleiotropic calcium signaling. These fluctuations reduce the threshold for calcium activation of transcription factors, while oscillation frequency may activate certain transcription factors like Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) (Dolmetsch et al., 1998). Spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ oscillations are present in human MSCs due to autocrine/paracrine ATP signaling to P2Y1 receptors (Kawano et al., 2002, 2003, 2006). As adipocytes differentiate, Ca2+ oscillations do not occur and NFAT does not translocate to the nucleus (Kawano et al., 2006). During differentiation and proliferation, these Ca2+ oscillations may play a large role in regulating the Ca2+ signal (Clapham, 1995; Thomas et al., 1996; Berridge et al., 2000, 2003; Schuster et al., 2002).

Conclusion

Signaling molecules, including adenosine, that bind to G-protein coupled receptors represent a novel approach to the obesity epidemic. Pharmacologic agents acting on these receptors may impact adipocyte differentiation. Understanding cell fate decisions could provide new insights into how adipogenesis affects metabolic homeostasis and could represent a viable target for treating or preventing obesity and its associated consequences. Although more mechanistic information is needed, the findings presented in this review highlight the importance of these receptors and ligands in the control of adipogenesis and present a new path to pursue. It appears that receptors coupled to Gαi proteins promote differentiation, while receptors coupled to Gαs inhibit adipocyte differentiation (Table 1). It is not clear, however, whether these actions are primarily due to activation of cAMP and PKA, or due to other mechanisms, particularly given the conflicting evidence on the role of cAMP in adipogenesis. In addition it appears that receptors coupled to Gαq proteins promote adipogenesis. The ability of a receptor to promote or inhibit adipocyte differentiation may also depend on the receptor density and on when the receptor is expressed during differentiation.

TABLE 1.

The role of G-protein coupled receptors in adipogenesis

| Receptor | Cell type | Effect on adipogenesis | Mechanism | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couples to Gas | ||||

| A2aAR | MSCs | Promotes | Increase PPARγand C/EBPα | Gharibi et al. (2011) |

| A2bAR | 752 cells | Inhibits | Unknown | Gharibi et al. (2012) |

| β2-AR/β3-AR | MSCs | Inhibits | Via activation of PKA | Li et al. (2010) |

| TSH receptor | 3T3-L1 | Inhibits | Decrease PPARγ due to inhibition of FOXOI |

Zhang et al. (2009) |

| TSH receptor | ESCs | Promotes | Unknown | Lu and Lin (2008) |

| Couples to Gγq | ||||

| P2Y | 3T3-L1 | Promotes | Alters actin cytoskeleton and induces cell migration |

Omatsu-Kanbe et al. (2006) |

| P2Y1/P2Y4 | MSCs | Promotes | Unknown | Ciciarello et al. (2013) |

| GPR120 | 3T3-L1, primary preadipocytes |

Promotes | Unknown | Gotoh et al. (2007), Ichimura et al. (2012) |

| Prostaglandin F2α receptor |

3T3-L1 | Inhibits | Calcineurin dependent inhibition of PPARγ and C/EBPα |

Liu and Clipstone (2007) |

| GPR103 | 3T3-L1 | Promotes | Increase fat storage and decrease lipolysis | Mulumba et al. (2010) |

| Couples to Gαi | ||||

| A1AR | MSCs, 752 cells, ob17 cells |

Promotes | Enhances lipogenesis |

Gharibi et al. (2011), Gharibi et al. (2012), Tatsis-Kotsidis and Erlanger (1999a,b) |

| GPCR43 | 3T3-L1 | Promotes | Unknown | Hong et al. (2005) |

One promising ligand, adenosine, and stable analogs, agonists and antagonists of its associated receptors, particularly the A2aAR and A2bAR, appear to play an important role in stem cell differentiation to various lineages. These receptors would be a good target for drug therapy that might either promote or inhibit differentiation. More details are needed prior to the implementation of a therapeutic strategy to target obesity, however, this area of research could potentially yield significant public health benefits.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant (HL93149 to K.R.), and by the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center (DK046200 to K.R.), an established Investigator with the American Heart Association. A.S.E. was supported by the Cardiovascular Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL007969) and by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases NRSA F30 award (DK098834). We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contract grant sponsor: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute;

Contract grant number: HL93149.

Contract grant sponsor: Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center;

Contract grant number: DK046200.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health;

Contract grant number: HL007969.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases;

Contract grant number: DK098834.

Literature Cited

- Abbott WG, Foley JE. Comparison of body composition, adipocyte size, and glucose and insulin concentrations in Pima Indian and Caucasian children. Metabolism. 1987;36:576–579. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: Update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: From molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altiok S, Xu M, Spiegelman BM. PPARgamma induces cell cycle withdrawal: Inhibition of E2F/DP DNA-binding activity via down-regulation of PP2A. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1987–1998. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner E, Westermark PO, Spalding KL, Britton T, Ryden M, Frisen J, Bernard S, Arner P. Adipocyte turnover: Relevance to human adipose tissue morphology. Diabetes. 2010;59:105–109. doi: 10.2337/db09-0942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsoy K, Soukas A, Torrens J, Ceccarini G, Montez J, Maffei M, Cohen P, Fayzikhodjaeva G, Viale A, Socci ND, Friedman JM. Cellular program controlling the recovery of adipose tissue mass: An in vivo imaging approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12985–12990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805621105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P, Karlsson M, Pettersson P, Sypniewska G. Differentiation and function of rat adipocyte precursor cells in primary culture. J Lipid Res. 1980;21:714–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone C, Gregoire F, Remacle C. Various stimulators of the cyclic AMP pathway fail to promote adipose conversion of porcine preadipocytes in primary culture. Differentiation. 1999;64:255–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1999.6450255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borglum JD, Vassaux G, Richelsen B, Gaillard D, Darimont C, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. Changes in adenosine A1- and A2-receptor expression during adipose cell differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;117:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes R, Arad R, Benvenisty N, Weil S, Bar-Tana J. The induction of adipose conversion by bezafibrate in 3T3-L1 cells. Synergism with dibutyryl-cAMP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1054:219–224. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: Regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, Eilert MM, Tcheang L, Daniels D, Muir AI, Wigglesworth MJ, Kinghorn I, Fraser NJ, Pike NB, Strum JC, Steplewski KM, Murdock PR, Holder JC, Marshall FH, Szekeres PG, Wilson S, Ignar DM, Foord SM, Wise A, Dowell SJ. The Orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Umek RM, McKnight SL. Regulated expression of three C/EBP isoforms during adipose conversion of 3T3-L1 cells. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1538–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L, Marcus-Samuels B, Mason MM, Moitra J, Vinson C, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Adipose tissue is required for the antidiabetic, but not for the hypolipidemic, effect of thiazolidinediones. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1221–1228. doi: 10.1172/JCI11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheepala S, Hulot JS, Morgan JA, Sassi Y, Zhang W, Naren AP, Schuetz JD. Cyclic nucleotide compartmentalization: Contributions of phosphodiesterases and ATP-binding cassette transporters. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Chen H, Nguyen A, Gupta D, Wang J, Lai EW, Pacak K, Gavrilova O, Quon MJ, Weinstein LS. G(s)alpha deficiency in adipose tissue leads to a lean phenotype with divergent effects on cold tolerance and diet-induced thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2010;11:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JT, Liu IM, Chi TC, Shinozuka K, Lu FH, Wu TJ, Chang CJ. Role of adenosine in insulin-stimulated release of leptin from isolated white adipocytes of Wistar rats. Diabetes. 2000;49:20–24. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciarello M, Zini R, Rossi L, Salvestrini V, Ferrari D, Manfredini R, Lemoli RM. Extracellular purines promote the differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1097–1111. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 1995;80:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth E., Jr. Failure of adipocyte differentiation causes type II diabetes mellitus? Nat Genet. 2000;26:13. doi: 10.1038/79111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington GJ, Ross SE, MacDougald OA. The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30057–30060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis-Henriot D, de Mazancourt P, Morot M, Giudicelli Y. Mutant alpha-subunit of the G protein G12 activates proliferation and inhibits differentiation of 3T3-F442A preadipocytes. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2892–2899. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf EM, Ge Q, Bindels LB, Sohet FM, Cani PD, Brichard SM, Delzenne NM. Evaluation of the relationship between GPR43 and adiposity in human. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2013;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:933–936. doi: 10.1038/31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Ginsberg HN, Erlanger BF. Overexpression of the A1 adenosine receptor in adipose tissue protects mice from obesity-related insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2001;3:360–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BA, Elford C, Pexa A, Francis K, Hughes AC, Deussen A, Ham J. Human osteoblast precursors produce extracellular adenosine, which modulates their secretion of IL-6 and osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:228–236. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspe E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, Najib J, Laville M, Fruchart JC, Deeb S, Vidal-Puig A, Flier J, Briggs MR, Staels B, Vidal H, Auwerx J. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18779–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajas L, Schoonjans K, Gelman L, Kim JB, Najib J, Martin G, Fruchart JC, Briggs M, Spiegelman BM, Auwerx J. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression by adipocyte differentiation and determination factor 1/sterol regulatory element binding protein 1: Implications for adipocyte differentiation and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5495–5503. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D, Gulinelli S, Salvestrini V, Lucchetti G, Zini R, Manfredini R, Caione L, Piacibello W, Ciciarello M, Rossi L, Idzko M, Ferrari S, Di Virgilio F, Lemoli RM. Purinergic stimulation of human mesenchymal stem cells potentiates their chemotactic response to CXCL12 and increases the homing capacity and production of proinflammatory cytokines. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:360–374. 374 e361–374 e365. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KE, Fankell DM, Erickson PF, Majka SM, Crossno JT, Jr., Klemm DJ. Depletion of cAMP-response element-binding protein/ATF1 inhibits adipogenic conversion of 3T3-L1 cells ectopically expressing CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) alpha, C/EBP beta, or PPAR gamma 2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40341–40353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KE, Colton LA, Erickson PF, Friedman JE, Cha HC, Keller P, MacDougald OA, Klemm DJ. Regulation of cyclin D1 and Wnt10b gene expression by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein during early adipogenesis involves differential promoter methylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35096–35105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806423200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Release of adenosine-like material from isolated perfused dog adipose tissue following sympathetic nerve stimulation and its inhibition by adrenergic alpha-receptor blockade. Acta Physiol Scand. 1976;96:122–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Effect of adenosine, adenosine analogues and drugs inhibiting adenosine inactivation on lipolysis in rat fat cells. Acta Physiol Scand. 1978;102:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Sollevi A. The release of adenosine and inosine from canine subcutaneous adipose tissue by nerve stimulation and noradrenaline. J Physiol. 1981;313:351–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freytag SO, Paielli DL, Gilbert JD. Ectopic expression of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha promotes the adipogenic program in a variety of mouse fibroblastic cells. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1654–1663. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukusumi S, Yoshida H, Fujii R, Maruyama M, Komatsu H, Habata Y, Shintani Y, Hinuma S, Fujino M. A new peptidic ligand and its receptor regulating adrenal function in rats. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46387–46395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukusumi S, Fujii R, Hinuma S. Recent advances in mammalian RFamide peptides: The discovery and functional analyses of PrRP, RFRPs and QRFP. Peptides. 2006;27:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, Graham D, Kim JK, Shulman GI, Castle AL, Vinson C, Eckhaus M, Reitman ML. Surgical implantation of adipose tissue reverses diabetes in lipoatrophic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:271–278. doi: 10.1172/JCI7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi B, Abraham AA, Ham J, Evans BA. Adenosine receptor subtype expression and activation influence the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblasts and adipocytes. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2112–2124. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi B, Abraham AA, Ham J, Evans BA. Contrasting effects of A1 and A2b adenosine receptors on adipogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:397–406. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard J, Perdereau D, Foufelle F, Prip-Buus C, Ferre P. Regulation of lipogenic enzyme gene expression by nutrients and hormones. FASEB J. 1994;8:36–42. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.1.7905448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser T, Cappellari AR, Pillat MM, Iser IC, Wink MR, Battastini AM, Ulrich H. Perspectives of purinergic signaling in stem cell differentiation and tissue regeneration. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh C, Hong YH, Iga T, Hishikawa D, Suzuki Y, Song SH, Choi KC, Adachi T, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G, Sasaki S, Roh SG. The regulation of adipogenesis through GPR120. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H, Kehinde O. Spontaneous heritable changes leading to increased adipose conversion in 3T3 cells. Cell. 1976;7:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H, Meuth M. An established pre-adipose cell line and its differentiation in culture. Cell. 1974;3:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Arany Z, Seale P, Mepani RJ, Ye L, Conroe HM, Roby YA, Kulaga H, Reed RR, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature. 2010;464:619–623. doi: 10.1038/nature08816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Mepani RJ, Kleiner S, Lo JC, Khandekar MJ, Cohen P, Frontini A, Bhowmick DC, Ye L, Cinti S, Spiegelman BM. Zfp423 expression identifies committed preadipocytes and localizes to adipose endothelial and perivascular cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauner H. Complete adipose differentiation of 3T3 L1 cells in a chemically defined medium: Comparison to serum-containing culture conditions. Endocrinology. 1990;127:865–872. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-2-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med. 2005;11:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Suzuki M, Ishii R, Satow R, Uchida T, Kitazumi T, Sasaki T, Kitamura T, Yamaguchi H, Nakamura Y, Fukami K. Genetic defect in phospholipase Cdelta1 protects mice from obesity by regulating thermogenesis and adipogenesis. Diabetes. 2011;60:1926–1937. doi: 10.2337/db10-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho IC, Kim JH, Rooney JW, Spiegelman BM, Glimcher LH. A potential role for the nuclear factor of activated T cells family of transcriptional regulatory proteins in adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15537–15541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YH, Nishimura Y, Hishikawa D, Tsuzuki H, Miyahara H, Gotoh C, Choi KC, Feng DD, Chen C, Lee HG, Katoh K, Roh SG, Sasaki S. Acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids stimulate adipogenesis via GPCR43. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5092–5099. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Deans RJ, Krause DS, Keating A. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura A, Hirasawa A, Poulain-Godefroy O, Bonnefond A, Hara T, Yengo L, Kimura I, Leloire A, Liu N, Iida K, Choquet H, Besnard P, Lecoeur C, Vivequin S, Ayukawa K, Takeuchi M, Ozawa K, Tauber M, Maffeis C, Morandi A, Buzzetti R, Elliott P, Pouta A, Jarvelin MR, Korner A, Kiess W, Pigeyre M, Caiazzo R, Van Hul W, Van Gaal L, Horber F, Balkau B, Levy-Marchal C, Rouskas K, Kouvatsi A, Hebebrand J, Hinney A, Scherag A, Pattou F, Meyre D, Koshimizu TA, Wolowczuk I, Tsujimoto G, Froguel P. Dysfunction of lipid sensor GPR120 leads to obesity in both mouse and human. Nature. 2012;483:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson PA, Pellme F, Hammarstedt A, Sandqvist M, Brekke H, Caidahl K, Forsberg M, Volkmann R, Carvalho E, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Wiklund O, Yang X, Taskinen MR, Smith U. A novel cellular marker of insulin resistance and early atherosclerosis in humans is related to impaired fat cell differentiation and low adiponectin. FASEB J. 2003;17:1434–1440. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1132com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Luo L, Gustafson EL, Yadav D, Laverty M, Murgolo N, Vassileva G, Zeng M, Laz TM, Behan J, Qiu P, Wang L, Wang S, Bayne M, Greene J, Monsma F, Jr., Zhang FL. Identification and characterization of a novel RF-amide peptide ligand for orphan G-protein-coupled receptor SP9155. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27652–27657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson SM, Salehi A, Sandstrom ME, Westerblad H, Lundquist I, Carlsson PO, Fredholm BB, Katz A. A1 receptor deficiency causes increased insulin and glucagon secretion in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1628–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katebi M, Soleimani M, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptors play an active role in mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell development. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:438–444. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano S, Shoji S, Ichinose S, Yamagata K, Tagami M, Hiraoka M. Characterization of Ca(2+) signaling pathways in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano S, Otsu K, Shoji S, Yamagata K, Hiraoka M. Ca(2+) oscillations regulated by Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger and plasma membrane Ca(2+) pump induce fluctuations of membrane currents and potentials in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano S, Otsu K, Kuruma A, Shoji S, Yanagida E, Muto Y, Yoshikawa F, Hirayama Y, Mikoshiba K, Furuichi T. ATP autocrine/paracrine signaling induces calcium oscillations and NFAT activation in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2006;39:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JB, Spiegelman BM. ADD1/SREBP1 promotes adipocyte differentiation and gene expression linked to fatty acid metabolism. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1096–1107. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JB, Sarraf P, Wright M, Yao KM, Mueller E, Solanes G, Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Nutritional and insulin regulation of fatty acid synthetase and leptin gene expression through ADD1/SREBP1. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:9–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutnikova H, Cock TA, Watanabe M, Houten SM, Champy MF, Dierich A, Auwerx J. Compensation by the muscle limits the metabolic consequences of lipodystrophy in PPAR gamma hypomorphic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14457–14462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336090100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, Satoh S, Nakano R, Ishii C, Sugiyama T, Eto K, Tsubamoto Y, Okuno A, Murakami K, Sekihara H, Hasegawa G, Naito M, Toyoshima Y, Tanaka S, Shiota K, Kitamura T, Fujita T, Ezaki O, Aizawa S, Nagai R, Tobe K, Kimura S, Kadowaki T. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999;4:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ. Seven transmembrane receptors: Something old, something new. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;190:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2007.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekstrom-Himes J, Xanthopoulos KG. Biological role of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28545–28548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang D, Zhou Y, Zhou B, Yang Y, Chen H, Song J. Protein kinase A suppresses the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Cell Res. 2008;18:311–323. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Fong C, Chen Y, Cai G, Yang M. Beta-adrenergic signals regulate adipogenesis of mouse mesenchymal stem cells via cAMP/PKA pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FT, Lane MD. Antisense CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein RNA suppresses coordinate gene expression and triglyceride accumulation during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Genes Dev. 1992;6:533–544. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FT, Lane MD. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha is sufficient to initiate the 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8757–8761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J. Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: Receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:775–787. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Clipstone NA. Prostaglandin F2α inhibits adipocyte differentiation via a G alpha q-calcium-calcineurin-dependent signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:161–173. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Malbon CC, Wang HY. Identification of amino acid residues of Gsalpha critical to repression of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11685–11694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Lin RY. TSH stimulates adipogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:159–169. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren M, Svensson M, Lindmark S, Renstrom F, Ruge T, Eriksson JW. Fat cell enlargement is an independent marker of insulin resistance and ‘hyperleptinaemia’. Diabetologia. 2007;50:625–633. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0572-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity. QJM. 2006;99:565–579. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnachie G, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. AKAP signaling complexes: Getting to the heart of the matter. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SG, De Vos P, Guerre-Millo M, Wong K, Hermann T, Staels B, Briggs MR, Auwerx J. The adipocyte specific transcription factor C/EBPalpha modulates human ob gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5507–5511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison RF, Farmer SR. Role of PPARgamma in regulating a cascade expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p18(INK4c) and p21(Waf1/Cip1), during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17088–17097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulumba M, Jossart C, Granata R, Gallo D, Escher E, Ghigo E, Servant MJ, Marleau S, Ong H. GPR103b functions in the peripheral regulation of adipogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1615–1625. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW, Clipstone NA. Calcineurin mediates the calcium-dependent inhibition of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49776–49781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrel R, Grimaldi P, Ailhaud G. Establishment of preadipocyte clonal line from epididymal fat pad of ob/ob mouse that responds to insulin and to lipolytic hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:6054–6058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntambi JM, Takova T. Role of Ca2+ in the early stages of murine adipocyte differentiation as evidenced by calcium mobilizing agents. Differentiation. 1996;60:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1996.6030151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno A, Tamemoto H, Tobe K, Ueki K, Mori Y, Iwamoto K, Umesono K, Akanuma Y, Fujiwara T, Horikoshi H, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Troglitazone increases the number of small adipocytes without the change of white adipose tissue mass in obese Zucker rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1354–1361. doi: 10.1172/JCI1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omatsu-Kanbe M, Inoue K, Fujii Y, Yamamoto T, Isono T, Fujita N, Matsuura H. Effect of ATP on preadipocyte migration and adipocyte differentiation by activating P2Y receptors in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem J. 2006;393:171–180. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpana HM, Berthelot JM, Kaplan MS, Feeny DH, McFarland B, Ross NA. BMI and mortality: Results from a national longitudinal study of Canadian adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:214–218. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto TC, Lane MD. Adipose development: From stem cell to adipocyte. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;40:229–242. doi: 10.1080/10409230591008189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, Daley GQ. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DA, Greenberg MJ. Structure of a molluscan cardioexcitatory neuropeptide. Science. 1977;197:670–671. doi: 10.1126/science.877582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid K, Lowenstein JM. Changes in adenosine receptors during differentiation of 3T3-F442A cells to adipocytes. Biochem J. 1988;249:377–381. doi: 10.1042/bj2490377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reusch JE, Colton LA, Klemm DJ. CREB activation induces adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1008–1020. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.1008-1020.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AM, Fain JN, Rivkees SA. A1 adenosine receptor activation increases adipocyte leptin secretion. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1442–1445. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard DJ, Wang FL, Rodriguez-Rojas AM, Wu Z, Trice WJ, Hoffman SJ, Votta B, Stroup GB, Kumar S, Nuttall ME. Intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH) as well as a non-peptide small molecule agonist of the PTH1 receptor inhibits adipocyte differentiation in human bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2006;39:1361–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K, Friedman JM. Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell. 2008;135:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, MacDougald OA. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:885–896. doi: 10.1038/nrm2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, Spiegelman BM, Mortensen RM. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph D, Tafuri A, Gass P, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B, Schutz G. Impaired fetal T cell development and perinatal lethality in mice lacking the cAMP response element binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4481–4486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W, Poll-Jordan G, Loffler G. Adipose conversion of 3T3-L1 cells in a serum-free culture system depends on epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factor I, corticosterone, and cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15489–15495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelch C, Kuhlmann J, Gossel M, Mueller G, Neumann-Haefelin C, Belz U, Kalisch J, Biemer-Daub G, Kramer W, Juretschke HP, Herling AW. Characterization of adenosine-A1 receptor-mediated antilipolysis in rats by tissue microdialysis, 1H-spectroscopy, and glucose clamp studies. Diabetes. 2004;53:1920–1926. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster S, Marhl M, Hofer T. Modelling of simple and complex calcium oscillations. From single-cell responses to intercellular signalling. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1333–1355. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe U, Ebert R, Erbler HC. Adenosine release from isolated fat cells and its significance for the effects of hormones on cyclic 3′,5′-AMP levels and lipolysis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1973;276:133–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00501186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Halvorsen YD, Ellis PN, Wilkison WO, Zemel MB. Role of intracellular calcium in human adipocyte differentiation. Physiol Genomics. 2000;3:75–82. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.3.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smas CM, Chen L, Zhao L, Latasa MJ, Sul HS. Transcriptional repression of pref-1 by glucocorticoids promotes 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12632–12641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, Bernard S, Buchholz BA, Bergmann O, Blomqvist L, Hoffstedt J, Naslund E, Britton T, Concha H, Hassan M, Ryden M, Frisen J, Arner P. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008;453:783–787. doi: 10.1038/nature06902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman BM, Choy L, Hotamisligil GS, Graves RA, Tontonoz P. Regulation of adipocyte gene expression in differentiation and syndromes of obesity/diabetes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6823–6826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelska K, Nogowski L, Szkudelski T. The inhibitory effect of resveratrol on leptin secretion from rat adipocytes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:899–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu S, Sakurai T, Iwasaki S, Teranishi H, Yamanaka A, Williams SC, Iguchi H, Kawasawa YI, Ikeda Y, Sakakibara I, Ohno K, Ioka RX, Murakami S, Dohmae N, Xie J, Suda T, Motoike T, Ohuchi T, Yanagisawa M, Sakai J. A neuropeptide ligand of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR103 regulates feeding, behavioral arousal, and blood pressure in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7438–7443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602371103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CY, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability: The metabolic problems of obesity may arise from the inability to become more obese. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:935–940. doi: 10.1042/BST0360935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Defective adipocyte differentiation in mice lacking the C/EBPbeta and/or C/EBPdelta gene. EMBO J. 1997;16:7432–7443. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Zeve D, Suh JM, Bosnakovski D, Kyba M, Hammer RE, Tallquist MD, Graff JM. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322:583–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsis-Kotsidis I, Erlanger BF. A1 adenosine receptor of human and mouse adipose tissues: Cloning, expression, and characterization. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999a;58:1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsis-Kotsidis I, Erlanger BF. Initiation of a process of differentiation by stable transfection of ob17 preadipocytes with the cDNA of human A1 adenosine receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999b;58:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AP, Bird GS, Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Putney JW., Jr. Spatial and temporal aspects of cellular calcium signaling. FASEB J. 1996;10:1505–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Kim JB, Graves RA, Spiegelman BM. AD D1: A novel helix-loop-helix transcription factor associated with adipocyte determination and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4753–4759. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Devine J, Beale EG, Spiegelman BM. PPAR gamma 2 regulates adipose expression of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995a;15:351–357. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of adipocyte gene expression and differentiation by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995b;5:571–576. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umek RM, Friedman AD, McKnight SL. CCAAT-enhancer binding protein: A component of a differentiation switch. Science. 1991;251:288–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1987644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassaux G, Gaillard D, Mari B, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. Differential expression of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors in preadipocytes and adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:1123–1130. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the Metabolic Syndrome—An allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Malbon CC. G(s)alpha repression of adipogenesis via Syk. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32159–32166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Watkins DC, Malbon CC. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to GS protein alpha-subunit sequence accelerate differentiation of fibroblasts to adipocytes. Nature. 1992;358:334–337. doi: 10.1038/358334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ND, Finegold MJ, Bradley A, Ou CN, Abdelsayed SV, Wilde MD, Taylor LR, Wilson DR, Darlington GJ. Impaired energy homeostasis in C/EBP alpha knockout mice. Science. 1995;269:1108–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.7652557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Johnson GL, Liu X, Malbon CC. Repression of adipogenesis by adenylyl cyclase stimulatory G-protein alpha subunit is expressed within region 146-220. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22022–22029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wang L, Shen M, Ma L. GRK5 deficiency decreases diet-induced obesity and adipogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer C, Foley JE, Bogardus C, Tataranni PA, Pratley RE. Enlarged subcutaneous abdominal adipocyte size, but not obesity itself, predicts type II diabetes independent of insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1498–1506. doi: 10.1007/s001250051560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederer O, Loffler G. Hormonal regulation of the differentiation of rat adipocyte precursor cells in primary culture. J Lipid Res. 1987;28:649–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. Induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma during the conversion of 3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes is mediated by C/EBPbeta, C/EBPdelta, and glucocorticoids. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4128–4136. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Rosen ED, Brun R, Hauser S, Adelmant G, Troy AE, McKeon C, Darlington GJ, Spiegelman BM. Cross-regulation of C/EBP alpha and PPAR gamma controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol Cell. 1999;3:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DC, Tsay HJ, Lin SY, Chiou SH, Li MJ, Chang TJ, Hung SC. cAMP/PKA regulates osteogenesis, adipogenesis and ratio of RANKL/OPG mRNA expression in mesenchymal stem cells by suppressing leptin. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarwood SJ, Anderson NG, Kilgour E. Cyclic AMP modulates adipogenesis in 3T3-F442A cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:175S. doi: 10.1042/bst023175s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh WC, Cao Z, Classon M, McKnight SL. Cascade regulation of terminal adipocyte differentiation by three members of the C/EBP family of leucine zipper proteins. Genes Dev. 1995;9:168–181. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeve D, Tang W, Graff J. Fighting fat with fat: The expanding field of adipose stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JW, Klemm DJ, Vinson C, Lane MD. Role of CREB in transcriptional regulation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta gene during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4471–4478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Qiu P, Arreaza MG, Simon JS, Golovko A, Laverty M, Vassileva G, Gustafson EL, Rojas-Triana A, Bober LA, Hedrick JA, Monsma FJ, Jr., Greene JR, Bayne ML, Murgolo NJ. P518/Qrfp sequence polymorphisms in SAMP6 osteopenic mouse. Genomics. 2007;90:629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Paddon C, Lewis MD, Grennan-Jones F, Ludgate M. Gsalpha signalling suppresses PPARgamma2 generation and inhibits 3T3L1 adipogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2009;202:207–215. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qi C, Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Noya D, Rao MS, Reddy JK. Structural organization of mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (mPPAR gamma) gene: Alternative promoter use and different splicing yield two mPPAR gamma isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7921–7925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]