Abstract

Chemical peeling implies the application of a chemical agent to the skin, which causes controlled destruction of a part or the entire epidermis, with or without the dermis, leading to exfoliation and removal of superficial lesions, followed by regeneration of new epidermal and dermal tissues. The present study was directed toward safety concerns associated with superficial chemical peeling with glycolic acid (GA) in different concentrations at patients with acne tip I. A sample of 90 patients of either sex, aged between 17 to 21 years, were included in the study and submitted to superficial chemical peeling for acne vulgaris. The study lasted eight weeks and peeling sessions were carried out in each patient. Tolerance to the procedure and any undesirable effects noted during these sessions were recorded. For data statistical analysis and interpretation of results, software program “SPSS version 13” was used. Results were expressed through the descriptive statistics, as simple frequencies and percentages, while for establishing of statistically significant differences, in use was Friedman’s test of significance. Almost all the patients tolerated the procedure well. Of totally 90 patients, only six, at the end of therapy experienced hard erythema, only ten, at the end of therapy experienced hard desquamation and only eleven, at the end of therapy experienced hard sensation of pulling of facial skin. Chemical peeling with glycolic acid is a well tolerated and safe treatment modality in acne type I.

KEY WORDS: superficial chemical peeling, glycolic acid, acne type I, side effects

INTRODUCTION

Chemical peeling implies the application of a chemical agent to the skin, which causes controlled destruction of a part or the entire epidermis, with or without the dermis, leading to exfoliation and removal of superficial lesions, followed by regeneration of new epidermal and dermal tissues [1]. Chemical peeling is a common office procedure that has evolved over the years, using the scientific knowledge of wound healing after controlled chemical skin injury [2]. Indications for chemical peeling include pigmentary disorders, superficial acne scars, ageing skin changes and benign epidermal growths [3]. Depending upon the type of peel, there may be a mild to severe sun burning sensation. There is a chance of reactivation of herpes simplex infection in patients with a history of fever blisters [4]. Prior to a chemical peel, it is important for the dermatologist to inquire about any past history of keloids, unusual scarring tendencies, extensive X-rays or radiation to the face, or recurring cold sores, for proper precautions to be taken [5]. It is important to avoid overexposure to the sun immediately after a chemical peel, since the new skin is fragile and more susceptible to injury [6, 7, 8]. This study was aimed, to evaluate the tolerance of superficial chemical peeling with glycolic acid (GA) in different concentrations at patients with acne tip I.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The study included 90 selected, healthy subjects, age ranged from 17 to 21 years, who with an exception of acne vulgaris, didn’t have other skin lesions and didn’t use the systemic retinoides six months before the beginning of treatment, nor topical retinoids, benzoyl peroxide and azelaic acid three months before the beginning of treatment. The study was conducted at the Centre of esthetic medicine within Healthy centre of Niš, and in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration, where each of the subjects agreed with a written consent for any procedures related to research. A sample of 90 subjects was divided into three sub-samples (each consisted of 30 subjects). To the first sub-sample it was applied 20% alpha-hydroxy acids, to the second sub-sample it was applied 35% alpha-hydroxy acids and to the third sub-sample it was applied 50% alpha-hydroxy acids. All subjects were treated once every two weeks. Treatment (superficial peel) lasted about 2-5 minutes. The study lasted eight weeks. Before peeling, the face was washed with soap and water to remove any make-up, dust and debris and was scrubbed with spirit gauze. Peeling was done with cotton wool applicator, dipped in required solution with smooth strokes to the affected areas, with patient’s closed eyes and plugged ears. The contact time of 5 minutes was enhanced sequentially with one minute increment on each subsequent visit. Avoidance of the use of soaps and sun exposure at least for one following day was strongly advised. Patients were prescribed sunscreens during daytime and panthenol cream at night. On each weekly visit, tolerance to the procedure and any undesirable effects during or just after peeling were noted. Any untoward happenings, experienced by the patients in between these sessions, were also recorded. All patients were followed up one month after the last peeling session and any adverse effects related to chemical peeling experienced by the patients during this period were nested in the protocol of research. Side effects of the treatment (erythema, desquamation and sensation of pulling of facial skin) were assessed by protocol from grade 0 to 3: (grade 0 = none, grade 1 = slightly, grade 2 = moderate, grade 3 = hard). Safety was assessed at each weekly visit by the incidence of side effects during the treatment as well as after one month follow-up.

Statistical analysis

For data statistical analysis and interpretation of results, software program “SPSS version 13” was used. Results were expressed through the descriptive statistics, as simple frequencies and percentages, while for establishing of statistically significant differences, in use was Friedman’s test of significance.

RESULTS

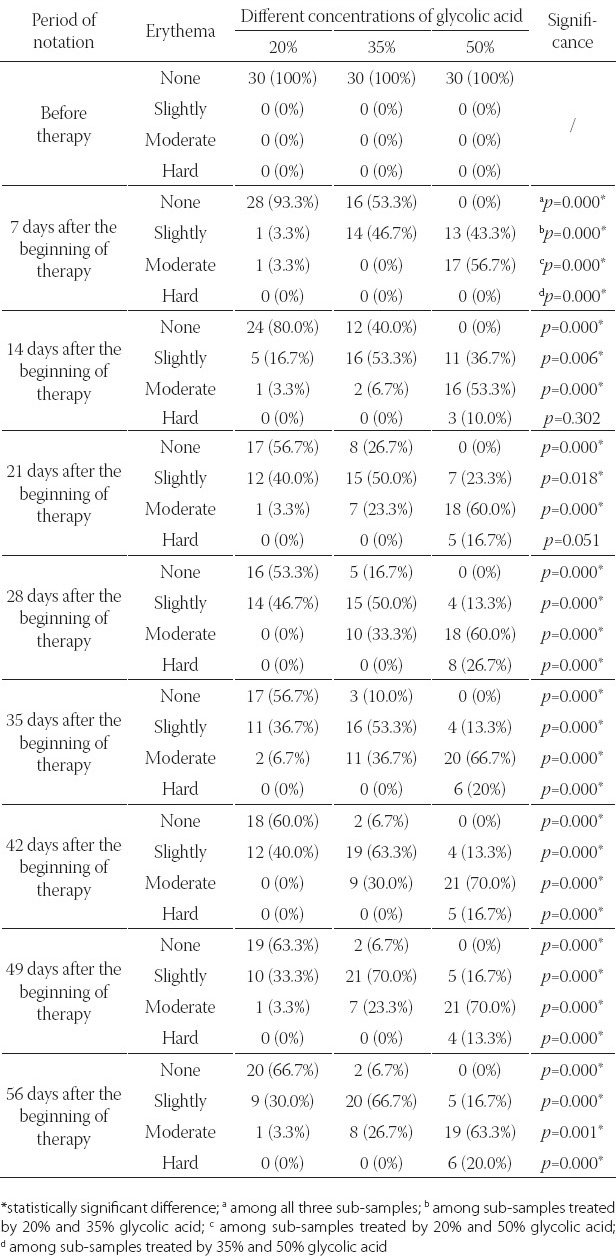

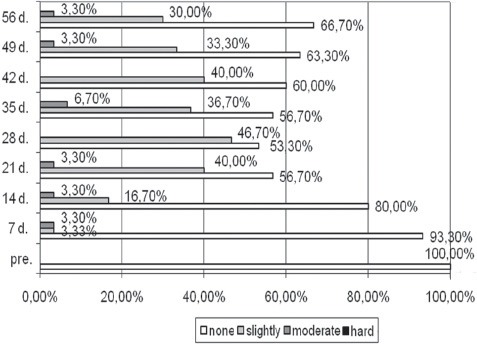

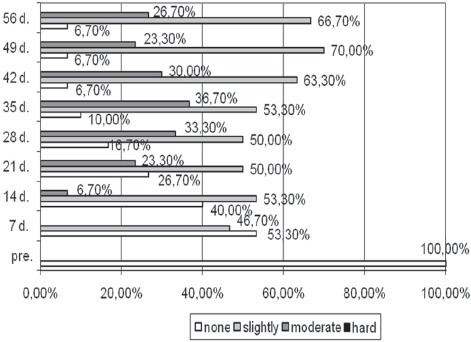

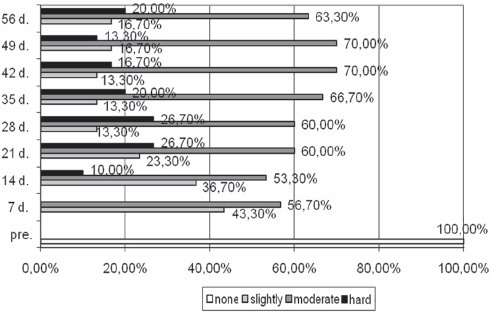

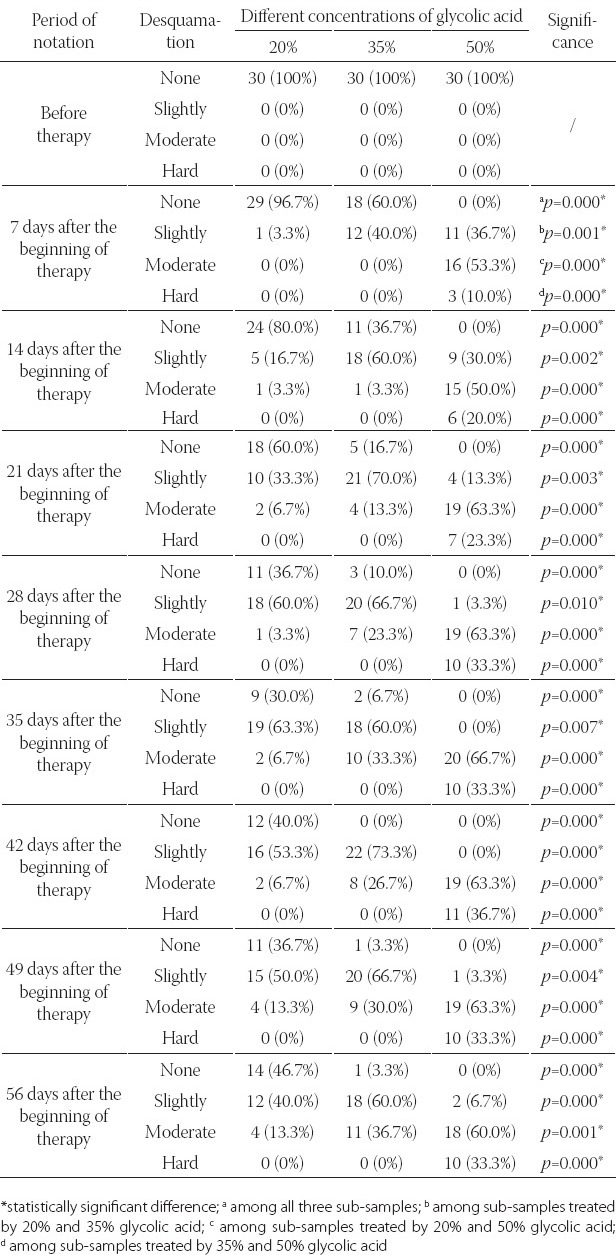

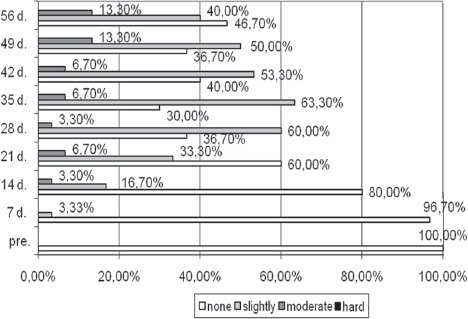

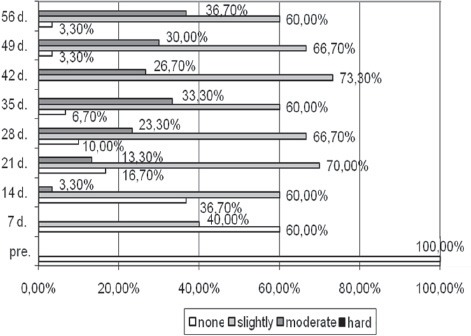

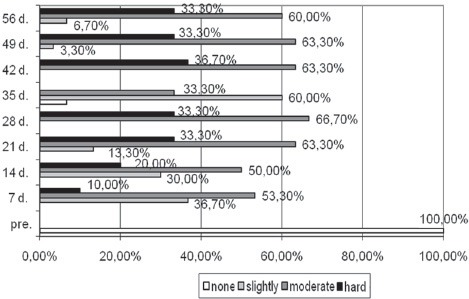

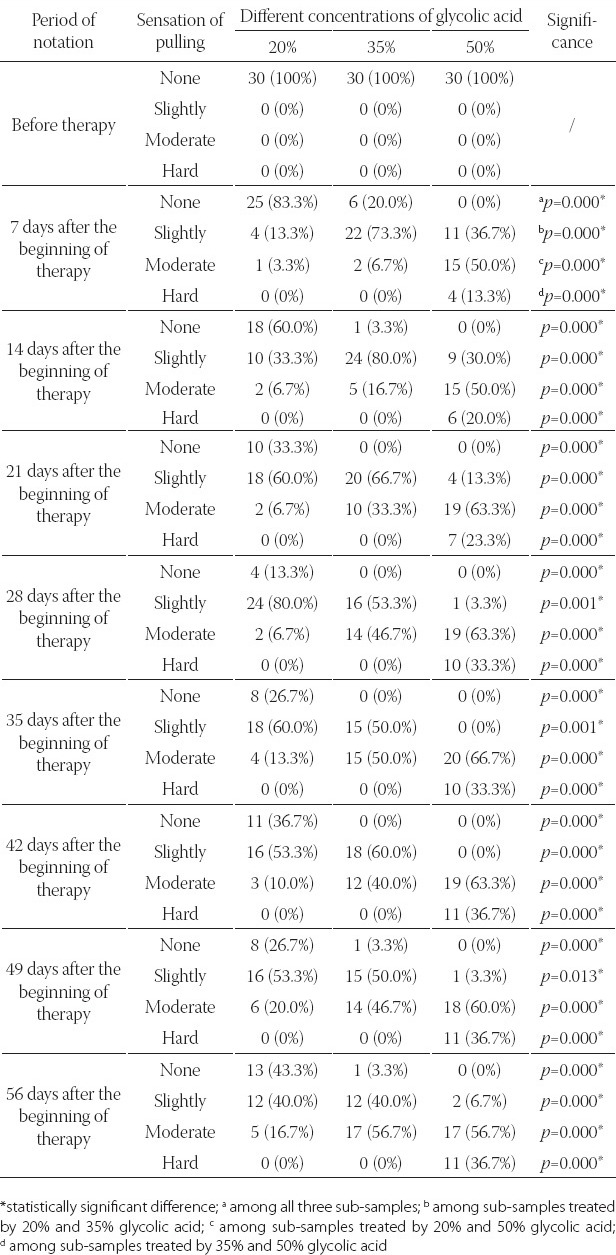

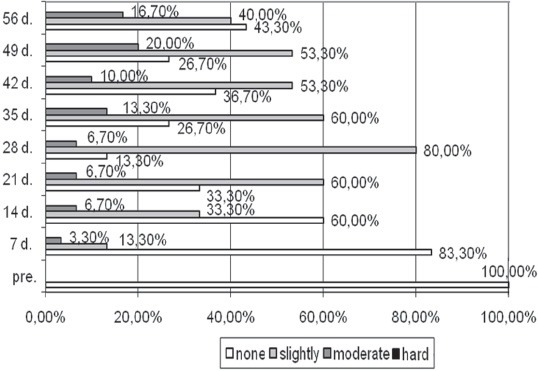

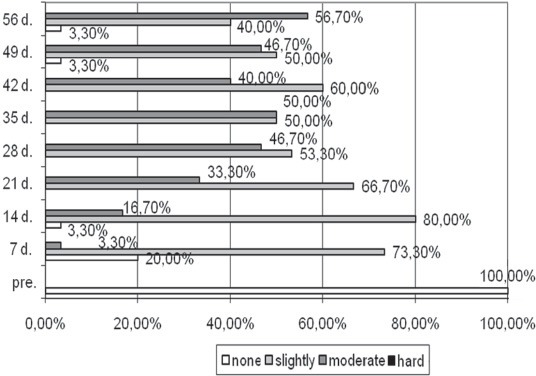

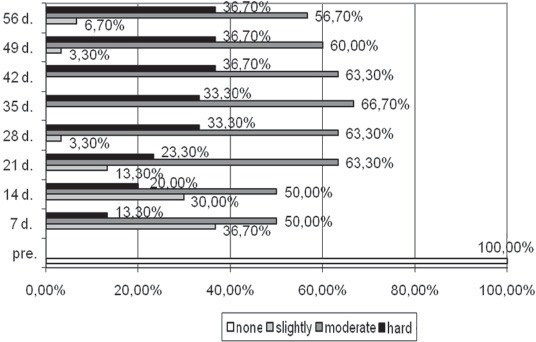

During the eighth weeks of monitoring in application of glycolic acid, significant increase in the prominence of erythema was noted in all three analyzed sub-samples (1st sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p=0.000; 2nd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p=0.000; 3rd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p=0.000) Table 1. Before beginning the therapy, none of the patients had erythema, while at the end of eight weeks, without erythema were two-thirds of subjects from the 1st sub-sample (Figure 1), less than io% of subjects from the 2nd subsample (Figure 2), while all subjects from the 3rd sub-sample had erythema (at the largest number of subjects of 3rd sub-sample, it was moderately expressed, Figure 3). Significant increase in the frequency of patients with the appearance of desquamation, as well as statistically increase in intensity of desquamation, was noted in all three analyzed sub-samples (1st sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p=0.000; 2nd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p = 0.000; 3rd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p = 0.000) (Table 2). Among these three sub-samples, a statistically significant difference in occurrence and intensity of desquamation was noted in all periods of observation, starting from the seventh to the fifty-sixth day of monitoring. The lowest significance in frequency of desquamation occurrence and its intensity had the subjects of 1st sub-sample (Figure 4). The subjects of 2nd sub-sample had significantly greater frequency of occurrence and intensity of desquamation, compared to the previous sub-sample (Figure 5), while the subjects of 3rd sub-sample had the biggest statistically significance of both of these changes, i.e., frequency and intensity of occurrence (Figure 6). During the eighth weeks of monitoring in application of glycolic acid, it was noticed a statistically significant increase in the frequency of subjects with sensation of pulling of face skin, as well as increased intensity of face skin sensation of pulling, in all three analyzed therapeutic sub-samples (1st sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p = 0.000; 2nd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p = 0.000; 3rd sub-sample i.e., Friedman’s test, p = 0.000), Table 3. Significantly the lowest frequency of occurrence of subjects with sensation of pulling of facial skin, and extent of its prominence, was noted in patients of 1st sub-sample (Figure 7). In the 2nd sub-sample (Figure 8), appearance and degree of pulling sensation of facial skin, was statistically significantly higher, than in the previous sub-sample of patients and significantly less than, at 5o% of patients of 3rd sub-sample. The highest significance of frequency in occurrence and intensity of the prominence of the subjective sense of skin pulling was noted in subjects of 3rd sub-sample (Figure 9).

TABLE 1.

Presence of side effect - erythema at all three sub-samples during therapy and significance of Friedman’s test.

FIGURE 1.

The appearance of erythema in the 1st sub-sample treated by 20% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 2.

The appearance of erythema in the 2nd sub-sample treated by 35% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 3.

The appearance of erythema in the 3rd sub-sample treated by 50% glycolic acid.

TABLE 2.

Presence of side effect - desquamation at all three sub-samples during therapy and significance of Friedman’s test.

FIGURE 4.

The appearance of desquamation in the 1st sub-sample treated by 20% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 5.

The appearance of desquamation in the 2nd sub-sample treated by 35% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 6.

The appearance of desquamation in the 3rd sub-sample treated by 50% glycolic acid

TABLE 3.

Presence of side effect - sensation of pulling at all three sub-samples during therapy and significance of Friedman’s test.

FIGURE 7.

The appearance of sensation of pulling in the 1st sub-sample treated by 20% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 8.

The appearance of sensation of pulling in the 2nd sub-sample treated by 35% glycolic acid.

FIGURE 9.

The appearance of sensation of pulling in the 3rd sub-sample treated by 50% glycolic acid.

DISCUSSION

Chemical peeling is based on the scientific principle of skin healing pattern seen with chemical burns. For centuries, this method of skin rejuvenation has been in vogue, though in less refined ways [9]. According to research conducted by Lee and Kim [10], this superficial peeling procedure is usually well tolerated in skin photo types III to VI. Also, almost all our patients tolerated the procedure very well. Of totally 90 patients, only six, at the end of therapy experienced hard erythema, only ten, at the end of therapy experienced hard desquamation and only eleven, at the end of therapy experienced hard sensation of pulling of facial skin. Others experienced slightly and moderate forms of analyzed side effects, immediately after application of the peeling agents, that lasted for a few minutes and gradually settled down within half an hour after washing the face. So, very few experienced it as an uncomfortable procedure but the vast majority graded it as a well-tolerated and acceptable experience. Obtained results are comparable to earlier studies with superficial peeling agents [4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Chemical peeling is a skin-wounding procedure, that can have some potentially undesirable side-effects and tolerance to this procedure, may vary from person to person [16, 17]. Acne of varying severity has been one of the well-evaluated indications for GA peels. Overall, 75-78 % of our patients with acne showed a good to fair response with GA peels as compared to 90% response seen by Wang et al. [18]. In the research conducted by Grover and Reddu [9], authors accented 11% patients with discomfort, which is in accordance with our research. Research conducted by Gupta et al. [5], pointed out on minimum side effects, with 52.5% concentration in form of erythema, or burning. The results of research are in accordance with research conducted by Klein and Little [19], where side-effects like laryngeal oedema, persistent erythema and swelling of the face did not occur.

CONCLUSION

Undesirable reactions (erythema, desquamation and sensation of pulling of facial skin) that occurred in our study were already expected. Mentioned reactions were easily manageable and did not affect the compliance of the patients. None of the patients developed post-inflammatory hyper or hypopigmentation of the affected or surrounding unaffected skin. More significantly, no serious side-effects like laryngeal oedema, persistent erythema and swelling of the face occurred. So, as a conclusion of this research, chemical peeling done by using glycolic acids is a well tolerated, safe and effective procedure that can be used at patients in treatment of acne type I.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Authors have neither any commercial affiliations, nor potential conflicts of interest associated with this work submitted for publication.

REFERENCES

- [1].Khunger N. Standard guidelines of care for chemical peels. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2008;74:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stegman SJ. A comparative histologic study of the effects of the three peeling agents and dermabrasion on normal and sun damaged skin. Aesth Plast Surg. 1982;6:123–135. doi: 10.1007/BF01570631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Monheit GD, Kayal JD. Chemical peeling. In: Nouri K, Leal-Khouri, editors. Techniques of Dermatologic Surgery. Elsevier; 2003. pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bari AU, Iqal Z, Sohai M, Rahman SB. Skin priming and efficacy of glycolic acid and salicylic acid in treatment of melasma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2002;12:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gupta RR, Mahajan BB, Garg G. Chemical peeling - Evaluation of glycolic acid in varying concentrations and time intervals. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Drake LA, Ceilley RI, Cornelison RL. Guidelines of care for office surgical facilities. Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:763–765. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Drake LA, Ceilley RI, Cornelison RL, Dinehart SM, Dorner W, Goltz RW, et al. Guidelines of care for office surgical facilities. Part II. Self-Assessment checklist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brody HJ. Complications of chemical resurfacing. Dermatol Clin. 2001;19:427–438. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Grover C, Reddy BS. The therapeutic value of glycolic acid peels in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69(2):148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1196–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2003.29384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Peric S, Bubanj M, Bubanj S. Effects of rendered superficial AHA's peelings with patients with acne comedonica et papulosa. Facta Universitatis. Series: Biology and Medicine. 2007;14(2):101–105. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ul Bari A, Iqbal Z, Ber Rehman S. Tolerance and safety superfitial chemical peeling with salicylic acid in various facijal dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:87–90. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.13990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kligman D, Kligman AM. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of photoaging. J Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:325–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lim JT, Tham SN. Glycolic acid peels in the treatment of melasma among Asian women. J Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Burns RL, Prevost-Blank PL, Lawry MA, Lawry TB, Faria DT, Fivenson DP. Glycolic acid peels for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in black patients. J Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Resnik SS, Resnik BI. Complications of chemical peeling. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:309–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Duffy MD. Alpha hydroxy acids/Trichloroacetic acids, risk/benefit strategies. A photographic review. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:181–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang CM, Huang CL, Hu CT, Chan HL. The effect of glycolic acid on treatment of acne in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Klein DR, Little JH. Laryngeal edema as a complication of chemical peel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:419–420. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198303000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]