Abstract

The most frequently used measuring instrument for determination of dental fear and anxiety (DFA) in children nowadays is the Dental Sub-scale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule (CFSS-DS). In this study we wanted to explore the reliability and validity of CFSS-DS scale in Bosnian children patients’ sample. There were 120 patients in the study, divided in three age groups (8, 12, and 15 years of age), with 40 patients in each group. Original CFSS-DS scale was translated into Bosnian language, and children’s version of a scale was used. The high value of the Cronbach’s coefficient of internal consistency (α=0.861) was found in the entire scale. Four factors were extracted by screen-test method with Eigen values higher than 1, which explained 63.79% variance of results. CFSS-DS scale is reliable and valid psychometric instrument for DFA evaluation in children in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The differences between our research and those of others may appear due to many factors.

KEY WORDS: reliability, validity, CFSS-DS, children, Bosnia and Herzegovina

INTRODUCTION

Psychometrics is the disciplinary home of a set of statistical models and methods that have been developed primarily to summarize, describe, and draw inferences from empirical data collected in psychological research [1]. It is necessary to explore psychometric characteristics of any measuring instrument before its use. Some of the basic psychometric characteristics of a measuring instrument are its reliability and validity [2, 3]. Reliability of a measuring instrument is its capability to measure phenomena precisely, and can be assessed by determination of internal consistency reliability with Cronbach’s α coefficient [4, 5]. Instrument validity is defined as the instrument capability to measure exactly what it is made for. One of the types of instrument validity is construct validity [5, 6]. One of the special means of construct validity determination is factor analysis. It is a method of determination of latent structure of results obtained with an instrument, which is based on the analysis of the connection of manifest or starting variables. The manifest variables are obtained by giving the values to components of a psychometric scale for example. Therefore, the variables obtained by factor analysis are linear combinations of manifest variables and are called latent (hidden). Considering this we can say that latent variables reveal the potential causes of the connection of phenomena [3, 7, 8, 9]. Despite the expansion of dental science and huge improvements in dental care, discontinuation in dental visits is still the main problem nowadays. The main reasons for avoiding the dentists are dental fear and anxiety (DFA). The most frequently used measuring instrument for determination of DFA in children nowadays is the Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule (CFSS-DS) [10, 11]. It was designed by Cuthbert and Melamed in 1982 [10], and is based on the instrument for measuring of fear presence in younger children, named Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSS-FC). FSS-FC was designed by Scherer and Nakamura [12]. In studies where CFSS-DS is compared with other available psychometric instruments for measuring of DFA presence in children it is shown that CFSS-DS scale has high reliability [11, 13, 14]. Beside its worldwide usage and high reliability, CFSS-DS scale has a simple and fast application, and represents cost-effective way for DFA evaluation. On the other hand, there are more variabilities in the analysis of CFSS-DS validity, although results are good (some authors think that some self-report measures of DFA are not capable to distinguish between general fear and anxiety and DFA) [15]. In this study we wanted to explore the reliability and validity of CFSS-DS scale in Bosnia and Herzegovina children patients’ sample, so that we could use this psychometric instrument in future for measuring DFA presence in children in our country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

There were 120 patients in the study, without any physical or psychiatric illness, or mental abnormality. Patients were divided in three age groups (8, 12, and 15 years of age), with 40 patients in each group. The sample comprised of 66 boys (55%) and 54 girls (45%). All examinees were regular patients of the Clinic for Preventive and Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sarajevo. Patients with symptoms of acute toothache or any other dental emergency (bleeding, swelling, dental trauma) were also excluded from the sample.

Procedures

Purpose of the study was explained in appropriate way to examinees and their parents, and parents gave the written consent for participation of their children in the study. Original CFSS-DS scale was translated into Bosnian language, and children’s version of a scale was used before the dental procedures were performed (children were filling the data, which is opposite to parent’s version of a scale where parents answer to the same questions instead of their children in the way how they assume that the children would feel in that situations). CFSS-DS scale has 15 dental and other situations, ranged by the Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 – not afraid, 5 – very afraid). Total score is between 15 and 75. Cut-off score for the evaluation of DFA presence in examinees is 38. Our research was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry of University of Sarajevo.

Statistical analysis

The following statistical methods were used in our research: descriptive statistics for age and sex sample distribution and the presence of results obtained with CFSS-DS scale in the sample; CFSS-DS scale reliability was determined by the Cronbach’s α coefficient of internal consistency; CFSS-DS scale validity was determined by exploring of construct validity with factor analysis with Varimax rotation. All statistical methods were done by SPSS 17.0 software package (SPSS Inc., USA) for Windows operative system.

RESULTS

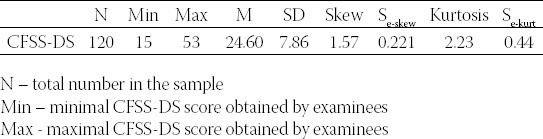

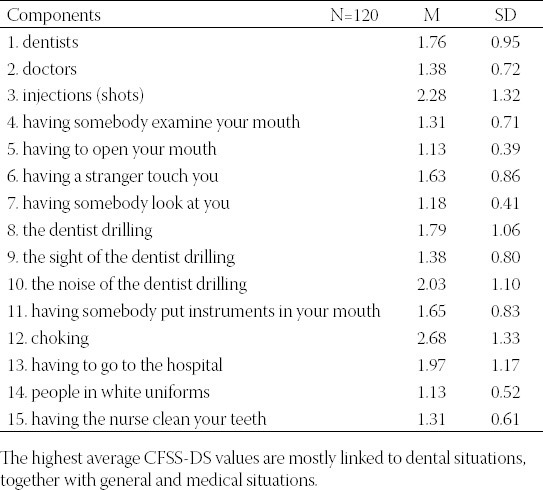

Distribution of results obtained with CFSS-DS scale in the sample is presented in Table 1. This distribution is asymmetrical because the skewness value is more than two times higher than its mistake. Table 2 represents the arithmetic means and standard deviations of results of CFSS-DS components in the sample. As it is shown from the Table 2 the highest average results values in our sample had the following CFSS-DS components: 12) choking, 3) injections, 10) the noise of the dentist drilling, 13) having to go to the hospital, 8) the dentist drilling and 1) dentists.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive values of results obtained with CFSS-DS scale

TABLE 2.

Arithmetic means and standard deviations of results of CFSS-DS components

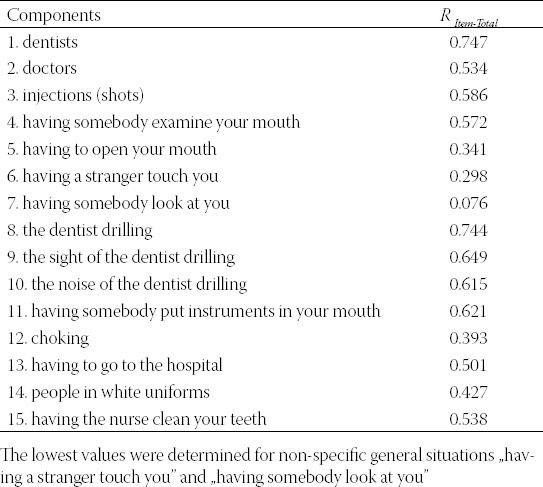

CFSS-DS scale reliability

We used the internal consistency determination procedure to explore the validity of results obtained by CFSS-DS scale. The high value of the Cronbach’s coefficient of internal consistency (α=0.861) was found in the entire scale. The Table 3 represents corrected values of item-total correlations.

TABLE 3.

Corrected values of item-total correlations

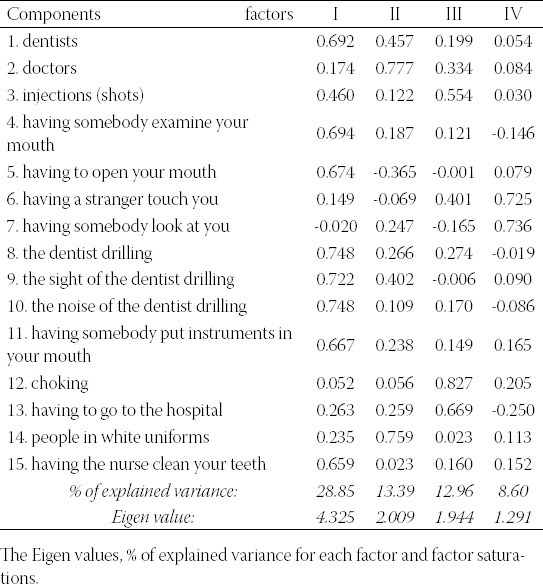

Factor analysis of CFSS-DS scale

Factor analysis of CFSS-DS components with Varimax rotation is applied in order to explore the validity of this psychometric instrument. Four factors were extracted by screen-test method with Eigen values higher than 1, which explained 63.79% variance of results. Results of analysis of CFSS-DS components are shown in Table 4. The first factor explained 28.85% of variance and was comprised of CFSS-DS components that describe the usual dental practice, including uncomfortable and painful treatments (cavity preparation for example). The second factor explained 13.39% of variance and included two components related to general fear from doctors in white coats. The third factor explained 12.96% of variance of results and relates to extreme situations (injections, choking, having to go to the hospital). Finally, the fourth factor was extracted, and it explained 8.6% of variance. This factor was related to unusual situations that did not belong to usual experiences in dental office or hospital surrounding, but represent general situations.

TABLE 4.

Rotated factorial matrix

DISCUSSION

Results of many studies support the high reliability of CFSS-DS scale as an instrument for measuring DFA presence in children [11]. Arapostathis et al. found that Cronbach’s coefficient α was 0.85 in Greek sample [16]. In the study of Nakai et al. from Japan [17], the high value of Cronbach’s coefficient is determined in CFSS-DS scale (α=0.89). Similar findings are also in the studies of ten Berge et al. [18] from Netherlands (α=0.85), Alvesalo et al. [19] from Finland (α=0.85) and Lee et al. [20] from Taiwan (α=0.90). Our result of Cronbach’s coefficient of internal consistency α is 0.86, and is in accordance with the above mentioned findings. We think that this result is based on precise and clear meaning of the questions in the CFSS-DS scale that were understandable and unequivocal to our patients, and that they were completely able to answer to these questions. Considering the factor structure of CFSS-DS scale, in the study of Nakai et al. [17] three factors were identified, which jointly explained 54.8% of variance of results. Factor I (explains 20.2% of variance) is characterized by fear from very invasive procedures. Factor II, characterized by fear from less invasive procedures, explains 19.7% of variance. Factor III, characterized by fear of potential victimization, explains 14.9% of variance of results. Milgrom et al. defined four factors in the sample of Chinese immigrant children, with 54% of variance explained [21]. Three factors were very similar to those from research from Japan [17], while the fourth additional factor appears as fear from touching or observing. Three factors were also defined in the study of ten Berge et al. [18], and the total variance of results is also significantly more explained than in the study in Japan (65%; factor I explains a big part of variance – 48%). However, the factor structure itself also differed, comparing to Japan study [17]. That was especially related to the second and third factor. Thereby factor II also contained issues related to fear from strangers, so it could be called fear from “less invasive aspects of dental treatment” (9.5% of variance). Because the structure of the third factor was also somewhat different, it could be called fear from “medical aspects” (7.5% of variance). Authors of this study said after their analysis that this kind of results indicated somewhat weak factor structure, and that CFSS-DS scale measures essentially primary one-dimensional concept of DFA, that could be defined as “fear from invasive aspects of treatment”. In another study from ten Berge et al. [22] stronger factor structure of CFSS-DS scale was found comparing to the previous study. Four factors were extracted, which altogether explain 60% of variance of results. Factors are: 1) fear from less invasive phases of dental treatment, 2) fear from medical aspects, 3) fear from cavity preparation, and 4) fear from strangers. In the study of Alvesalo et al. [19] three factors were also found, with 54% of variance explained. The sequence and structure of some factors quite differed in comparison to other studies. So, for example, factor II contained components related to fear from potential victimization (strangers, choking and hospital), and explained 9% of variance, while factor III (explained 9% of the variance) contained components related to fear from less invasive dental procedures (mouth opening, dental examination). Our results showed 63.79% of the variance explained, which is high value, and this mostly agrees with the findings of ten Berge et al. [18] in Dutch sample. The structure of the individual factors is mainly similar to those in other studies by character as well as composition. It has to be emphasized that four factors were extracted by factor analysis of CFSS-DS scale in our sample. The appearance of the fourth factor is in concordance with some other studies [21, 22]. It is also necessary to mention, regarding the factor structure in our study that not a single factor precedes in explaining of total variance of results, which is similar to study from Japan [19]. The differences between our research and those of others may appear due to many factors. Age differences of examinees influence different levels of perception and expression of DFA. Cultural differences and language characteristics and differences among examinees in the studies can also play an important role in obtained scores on CFSS-DS scale [21, 23, 24]. Thereby in our country there is lack of health awareness campaigns considering pretty bad oral health state (very high DMFT/dmft and other indexes of oral health). People in our country visit the dental office very rare in order to prevent oral health disease; dentists are being visited mostly when the problem is obvious and mostly very difficult to solve. These facts are different in other countries. The ways of filling the CFSS-DS scale (parent and child version of the instrument) can also have a great influence, considering that it is certain that parents cannot adequately evaluate the level of DFA presence in their children [25].

CONCLUSION

At the end we want to point out, considering the obtained results of our study, that CFSS-DS scale is reliable and valid psychometric instrument for DFA evaluation in children in Bosnia and Herzegovina, due to its further application for researches of DFA in our country.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by great efforts of complete staff of Clinic for Preventive and Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sarajevo.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

There is not any conflict of interest for this material in the manuscript for all authors, between the authors, or for any organization.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rao CR, Sinharay S. Vol. 26. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2007. Handbook of Statistics; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lu Y, Fang JQ. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2003. Advanced medical statistics; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Matthews DE, Farewell VT. Fourth edition. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2007. Using and Understanding Medical Statistics; pp. 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Everitt B. Second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. Medical statistics from A to Z. A guide for clinicians and medical students; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Feinstein AR. Boca Raton: A CRC Press Company; 2002. Principles of medical statistics; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fisher LD, van Belle G. Second edition. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2004. Biostatistics, A methodology for the health sciences; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Child D. Third edition. New York: Continuum; 2006. The Essentials of Factor Analysis; pp. 108–125. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gorsuch RL. Second edition. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. Factor Analysis; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Berggren U, Carlsson SG, Gustafsson JE, Hakeberg M. Factor analysis and reduction of a Fear Survey Schedule among dental phobic patients. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cuthbert MI, Melamed BG. A screening device: children at risk for dental fears and management problems. ASDC J Dent Child. 1982;49:432–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behavior management problems in children and adolescents: a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aartman IHA, van Everdingen T, Hoogstraten J, Schuurs AHB. Self-report measurements of dental anxiety and fear in children: a critical assessment. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].ten Berge M. Thesis. Amsterdam: University of Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam; 2001. Dental fear in children: Prevalence, etiology and risk factors. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Klingberg G. Dental anxiety and behaviour management problems in paediatric dentistry-a review of background factors and diagnostics. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9(Suppl 1):11–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03262650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Scherer MW, Nakamura CY. A fear survey schedule for children (FSS-FC): A factor analytic comparison with Manifest anxiety (CMAS) Behav Res Ther. 1968;6:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(68)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arapostathis KN, Coolidge T, Emmanouil D, Kotsanos N. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:374–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nakai Y, Hirakawa T, Milgrom P, Coolidge T, Heima M, Mori Y, et al. The Children's Fear Survey Schedule–Dental Subscale in Japan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:196–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].ten Berge M, Hoogstraten J, Veerkamp JSJ, Prins PJM. The Dental Subscale of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule: a factor analytic study in the Netherlands. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:340–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Alvesalo I, Murtomaa H, Milgrom P, Honkanen A, Karjalainen M, Tay KM. The dental fear survey schedule: a study with Finnish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1993;3:193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1993.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee CY, Chang YY, Huang ST. Higher-order exploratory factor analysis of the Dental subscale of Children's fear survey schedule in a Taiwanese population. Community Dent Health. 2009;26:183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Milgrom P, Jie Z, Yang Z, Tay KM. Cross-cultural validity of a parent's version of the Dental Fear Survey Schedule for children in Chinese. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J, Prins PJ. On the structure of childhood dental fear, using the Dental Subscale of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2002;3:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bergius M, Berggren U, Bogdanov O, Hakeberg M. Dental anxiety among adolescents in St. Petersburg, Russia. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105(2):117–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Berggren U, Pierce CJ, Eli I. Characteristics of adult dentally fearful individuals. A cross-cultural study. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108:268–274. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.108004268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luoto A, Tolvanen M, Rantavuori K, Pohjola V, Lahti S. Can parents and children evaluate each other's dental fear? Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:254–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]