Abstract

Background

Treatment options of recurrent malignant gliomas are very limited and with a poor survival benefit. The results from phase II trials suggest that the combination of bevacizumab and irinotecan is beneficial.

Patients and methods.

The medical documentation of 19 adult patients with recurrent malignant gliomas was retrospectively reviewed. All patients received bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) and irinotecan (340 mg/m2 or 125 mg/m2) every two weeks. Patient clinical characteristics, drug toxicities, response rate, progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were evaluated.

Results

Between August 2008 and November 2011, 19 patients with recurrent malignant gliomas (median age 44.7, male 73.7%, WHO performance status 0–2) were treated with bevacizumab/irinotecan regimen. Thirteen patients had glioblastoma, 5 anaplastic astrocytoma and 1 anaplastic oligoastrocytoma. With exception of one patient, all patients had initially a standard therapy with primary resection followed by postoperative chemoradiotherapy. Radiological response was confirmed after 3 months in 9 patients (1 complete response, 8 partial responses), seven patients had stable disease and three patients have progressed. The median PFS was 6.8 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.3–8.3) with six-month PFS rate 52.6%. The median OS was 7.7 months (95% CI: 6.6–8.7), while six-month and twelve-month survival rates were 68.4% and 31.6%, respectively. There were 16 cases of hematopoietic toxicity grade (G) 1–2. Non-hematopoietic toxicity was present in 14 cases, all G1-2, except for one patient with proteinuria G3. No grade 4 toxicities, no thromboembolic event and no intracranial hemorrhage were observed.

Conclusions

In recurrent malignant gliomas combination of bevacizumab and irinotecan might be an active regimen with acceptable toxicity.

Keywords: recurrent malignant glioma, bevacizumab, irinotecan, systemic therapy

Introduction

Malignant (high-grade) gliomas are rapidly progressive brain tumors comprising of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, anaplastic astrocytoma, mixed anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (all grade III, World Health Organization [WHO]) and glioblastoma (grade IV, WHO).1

The incidence of malignant gliomas is approximately 5/100,000. Malignant gliomas constitute 35–45% of primary brain tumors. Glioblastomas account for approximately 60 to 70% of malignant gliomas, while anaplastic astrocytomas represent 10 to 15%, and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligoastrocytomas 10% of malignant gliomas.1–3 The incidence of these tumors has increased slightly over past two decades, especially in the elderly. The peak incidence is in the fifth and sixth decade of life. The median age of patients at the time of diagnosis in the case of glioblastoma is 64 years and in the case of anaplastic gliomas is 45 years. Malignant gliomas are 40% more frequent in man than in woman and twice more frequent in white population than in black.2,4,5

In Slovenia from 1991 till 2005, a total of 1636 patients (878 males and 758 females) were diagnosed with brain cancer. Since 2001 till 2005 the microscopical verification was performed in 83% of cases: 82% were gliomas, of which two thirds were glioblastoma, 14% astrocytoma and 10% oligodendroglioma. Approximately 60% of the patients were diagnosed at age between 50 to 74 years, and 25% at age between 20 to 49 years.6

Glioblastoma tumors are gliomas of highest malignancy (grade IV), characterized by uncontrolled, aggressive cell proliferation and infiltrative growth within the brain and general resistance to conventional treatment. Despite the efforts to improve treatment outcome, the survival of patients with malignant gliomas is poor, with median survival of about 14 months.7,8 For glioblastoma, median time to progression after postoperative treatment with radiotherapy (RT) and temozolomide (TMZ) is 6,9 months and after RT alone 5.0 months.9 Although the 5-year OS analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial has shown benefit for patients treated with RT and TMZ compared with only irradiated patients (9.8% vs. 1.9%), the median survival after progression remains only 6.2 months10, regardless of the initial treatment.

We present single institution experience of treating recurrent malignant gliomas with combination of bevacizumab and irinotecan.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed medical documentation of 19 adult patients with recurrent malignant gliomas treated with bevacizumab and irinotecan at our center. All patients received bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg in combination with irinotecan 340 mg/m2 or 125 mg/m2 (with or without concomitant enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs, respectively) every two weeks. Patient clinical characteristics (pre-recurrence treatment, performance status at the baseline), drug toxicities, response rate (RR), progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were evaluated.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software, version 17.0. (SPSS Inc® Fulfillment center Haverhill MA, SPSS 17.0).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committe and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fourteen (73.7%) males and five (26.3%) females were included. Median age was 44.7 years (range 27–74). Thirteen patients had glioblastoma, 5 anaplastic astrocytoma and 1 anaplastic oligoastrocytoma. In our group WHO performance status was 0–2. As an initial therapy all patients had a standard therapy with primary resection followed by postoperative chemoradiotherapy, with three-dimensional (3D) conformal radiation therapy (3D CRT), with 56 Gy in 28 fractions, combined with TMZ 75mg/m2, and followed with TMZ 150-200mg/m2 (4–20 cycles), except for one patient, with anaplastic astrocytoma of medullary cone, who had only biopsy.

Treatment of recurrence

Bevacizumab and irinotecan systemic treatment was introduced after 1st, 2nd and 3rd recurrence in 12 (63.2%), 5 (26.3%) and 2 (10.5%) patients, respectively (Table 1). No patient received additional RT at the time of disease recurrence.

TABLE 1.

Systemic treatment of choice after disease progression

| Recurrence | Cht (number of patients) |

|---|---|

| First | Bevacizumab + Irinotecan 12 (63.2%) |

| BCNU 2 | |

| TMZ 4 | |

| PCV 1 | |

| Second | Bevacizumab + Irinotecan 5 (26.3%) |

| BCNU 1 | |

| PCV 1 | |

| Third | Bevacizumab + Irinotecan 2 (10.5%) |

BCNU = Carmustine (BCNU), 80 mg/m2 BCNU on days 1 on 3; Cht = chemotherapy; PCV = lomustine (CCNU), 110 mg/m2, on day 1; procarbazine, 60 mg/m2 on days 8 to 21; and vincristine, 1.5 mg/m2 (maximum dose, 2 mg), on days 8 and 29; TMZ = temozolomide, 150–200 mg/m2/day on days 1 to 5 of each subsequent 28-day cycle

Efficacy

Average number of chemotherapy applications was 9.3 (range 1–17). Median follow up of the patients was 10 months (range 0–34 months). Radiological response was confirmed after 3 months in nine patients (1 complete response, 8 partial responses), seven patients had stable disease, and 3 patients have progressed. After 6 months, one patient remained in complete response, five had partial response, five had stable disease and eight have progressed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Radiological response after 3 months and 6 months of concomitant irinotecan and bevacizumab treatment

| Response (n=19) | after 3 months | after 6 months |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Response (CR) | 1 | 1 |

| Partial Response (PR) | 8 | 5 |

| Stable Disease (SD) | 7 | 5 |

| Progression of Disease (PD) | 3 | 8 |

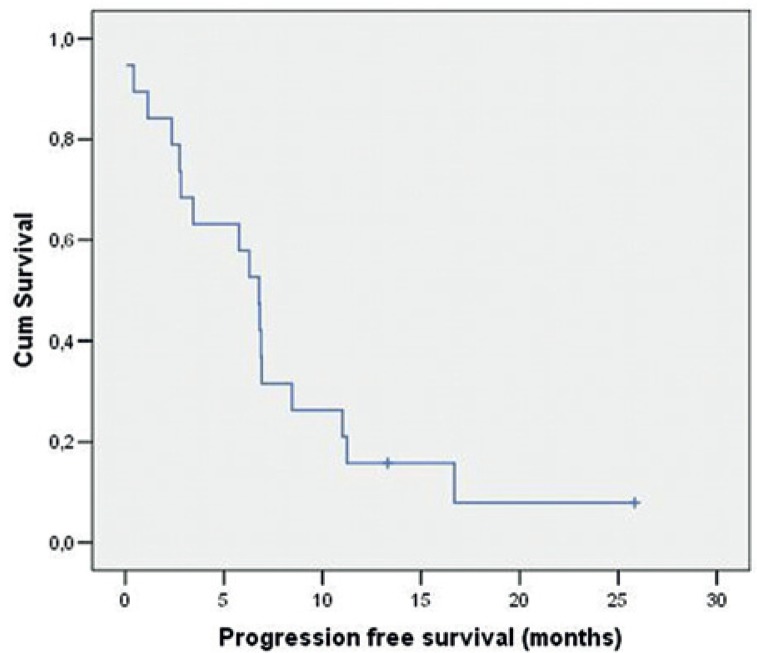

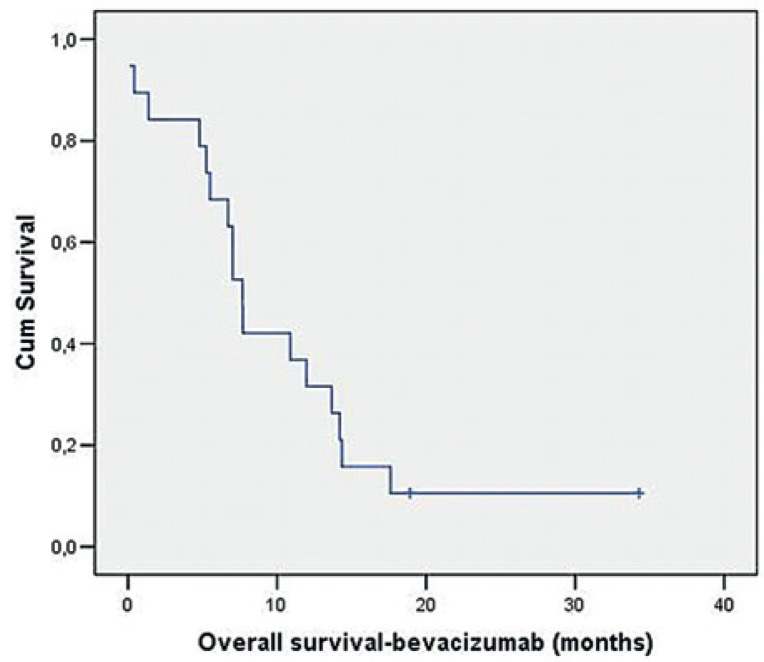

The median PFS was 6.8 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.3–8.3) (Figure 1) and the estimated six-month and twelve-month- PFS rates were 52.6% and 15.8%, respectively. The median OS was 7.7 months (95% CI: 6.6–8.7) (Figure 2), while the six-month and twelve-month survival rates were 68.4% and 31.6%, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

The median progression free survival (PFS).

FIGURE 2.

The median overall survival (OS).

Toxicity

Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0. There were 16 cases of hematopoietic toxicity, only one patient had G2 neutropenia whereas in others only G1 toxic events were recorded. Two patients had neutropenia, six had lymphopenia, two had thrombocytopenia and one patient had anemia. No febrile neutropenia was observed. Nonhematopoietic toxicity G1-2 was present in 14 patients, with exception of one patient with proteinuria G3. Non-hematopoietic adverse events were: arterial hypertension (3), proteinuria (7), vomiting (2), diarrhea (1) and muscle pain (1). There was no G4 toxicity, no thromboembolic events and no intracranial hemorrhage observed (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Adverse events

| Without AE n (%) |

G1 n (%) |

G2 n (%) |

G3 n (%) |

G4 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic toxicity | |||||

| leukopenia | 16 (84) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| neutropenia | 17 (89.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| lymphopenia | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| thrombocytopenia | 17 (89.5) | 2 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| anemia | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| febrile neutropenia | 0 | / | / | / | 0 |

| Non-hematopoietic toxicity | |||||

| arterial hypertension | 16 (84.2) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| proteinuria | 12 (63.2) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.2) | / |

| sepsis | 0 | / | / | / | 0 |

| diarrhea | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| vomiting | 17 (89.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| muscle pain | 18 (84.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | / | / |

| intracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| tromboembolic event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

0 = no adverse side effects; / = adverse events of this grade doesn’t exist

Discussion

Everyday reality is that, despite efforts to improve therapies or to develop new ones, the outcome of treatment in malignant gliomas is poor with median survival of 14 months.2

The treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas with RT is controversial. Some data have suggested that fractionated stereotactic reirradiation (SRT) and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), which are also effective in another diseases, may be beneficial.11,12 Observational series of patients with recurrent malignant gliomas, treated with SRT showed the median survival of 16 months for patients with grade III tumors and eight months for those with grade IV lesions.13 The one-year survival rates were 65% and 23% for patients with grade III and IV lesions, respectively. Kong et al. in a patients with recurrent gliomas treated with SRS has achieved progression free survival for patients with grade III and grade IV gliomas of 8.6 and 4.6 months, respectively.14 All patients were treated with SRS treatments delivered by gamma knife, except for 5 patients treated by linear accelerator.

Chemotherapy treatment is more effective for anaplastic gliomas than for glioblastoma, and in general has modest value for recurrent malignant gliomas. There is no established chemotherapy regimen available and patients are best treated within investigational clinical protocols.

TMZ was evaluated in a phase II study in patients with recurrent anaplastic gliomas who had previously been treated with nitrosoureas.15 The response rate was 35%, and the 6-month PFS rate was 46%, comparing favorably with the 6-month PFS rate of 31% for therapies that were generally considered ineffective.16 In patients with recurrent glioblastoma, TMZ has only limited activity, with response rate of 5.4% and 6-month rate of PFS of 21%.17

Other chemotherapeutic agents that are used for recurrent gliomas include nitrosoureas, carboplatin, procarbazine, irinotecan, and etoposide. Nitrosoureas (carmustine, fotemustine) either as single agents or in combination regimens as procarbazine, lomustine and vincristine (PCV) have shown activity in phase II studies in previously treated patients. Brandes AA et al., conducted a phase II study on 40 patients with recurrent glioblastoma following surgery and standard radio-therapy, treated with carmustine as monotherapy. Median time to progression was 13.3 weeks and progression-free survival at 6-months was 17.5%.18 Schmidt F et al., has applied PCV, as combined regimen, to 86 patients with recurrent glioblastoma. There were three partial responses, but no complete responses. Median progression-free survival was 17.1 weeks and progression-free survival at 6 months was 38.4%.19

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody, which binds to VEGF, the key driver of neovascularization, and thereby inhibits the binding of VEGF to its receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, on the surface of endothelial cells.

Anti-VEGF therapy, including bevacizumab, acts by binding to VEGF and preventing its cellular effects. However, this linear interaction represents only a partial view of the pathobiology of the disease and treatment processes. Consequently, the classical concept of linear interactions is being replaced by the concept of networks of interactions, emphasizing the importance of interactions between different components of a biologic system.20

In phase II studies Bevacizumab as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy agents such as irinotecan demonstrated clinical activity for patients with grade 3 and grade 4 malignant gliomas (higher objective response, progression-free survival and overall survival) in recurrent glioblastoma21–32 and in May 2009, it has been approved by FDA for the secondary treatment of glioblastoma in USA32, but it is not approved yet by EMA in Europe.34

According to the meta-analysis of phase II trials with bevacizumab and irinotecan treatment in recurrent malignant gliomas35, which included 411 patients, the median progression-free survival time ranged from 2.4 to 13.4 months and the median overall survival time ranged from 6.2 to 14.9 months, with response rates ranging from 28% to 86%. The improvement in tumor response rate observed in patients with reccurent malignant gliomas treated with bevacizumab and irinotecan combination to those on other systemic drugs protocols was highly statistically significant (P = 0.00002), and so was the same with the OS (P = 0.024).

The most extensive experience with bevacizumab comes from a noncomparative phase II trial, in which 167 patients with recurrent glioblastoma, previously treated with chemotherapy with temozolomide were randomly assigned to bevacizumab, either as a single agent or at the same dose in conjunction with irinotecan.24 Treatment cycles were repeated every two weeks. The objective response rates with bevacizumab alone or in combination with irinotecan were 28% and 38%, respectively, the 6-month PFS rates were 43% and 50%, respectively and mOS times were 9.2 and 8.7 months, respectively. An update of the results was presented at the 2010 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting.23 Overall safety and efficacy were similar to that previously presented; the 12 and 24-month survival rates were 38% and 16% to 17% on both treatment arms, which appear to be better than historical control series.

We treated 19 patients with recurrent malignant gliomas with bevacizumab and irinotecan, from August 2008 to November 2011. The objective response rates were 47.4% and 31.6% after 3 and 6 months respectively. The 6-month PFS and OS rate and interval were 52.6% and 68.4% and 6.8 and 7.7 months, respectively. One third of the patients (31.6%) reached twelve-month OS. Regarding toxicity, 78.9% patients experienced hematopoietic toxicity G1, with only one patient experiencing G2 neutropenia. As for the non-hematopoietic toxicity, 42.1% patients had adverse events G1, 26.3% G2 and one patient had G3 proteinuria. There were no grade 4 toxicities, no febrile neutropenia, no thromboembolic event and no intracranial hemorrhage observed. Comparison of our data with other studies is presented in the Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of our study data with other studies

| Patients | Response rate | PFS at 6 months | Median survival (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bev+Irinotecan(Vredenburgh)25 | 35 | 57% | 46% | 9.7 |

| Bev→Bev+Irinotecan (Kreisl)21 | 85 | 35% | 29% | 7.2 |

| Bev+Irinotecan (Friedman)22 | 167 | 28% / 38% | 43% / 53% | 9.2 / 8.7 |

| Bev+Irinotecan (IO Lj study) | 19 | 47.4% | 52.6% | 7.7 |

IO Lj = Institute of Oncology Ljubljana

Conclusions

In patients with recurrent malignant gliomas the combination of bevacizumab and irinotecan shows promising activity with acceptable toxicity although survival outcome is far from desired. Our results of the treatment of patients with recurrent malignant gliomas, regarding response rate, PFS and OS are comparable with the previously published data.

As all data about efficacy and safety of bevacizumab and irinotecan therapy in recurrent malignant gliomas are coming from phase II trials, larger phase III randomized controlled studies comparing bevacizumab plus irinotecan with other treatment protocols are warranted so that the efficacy can be assessed properly.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CBTRUS, Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States 2007–2008. Primary brain tumors in the United States. Statistical report. 2000–2004 years of data collected. Available from: http://www.cbtrus.org/reports/2007-2008/2007report.pdf. Accessed on 10 November 2013.

- 3.Kase M, Minajeva A, Niinepuu K, Kase S, Vardja M, Asser T, et al. Impact of CD133 positive stem cell proportion on survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:405–10. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JL, Schwartzbaum JA, Wrensch M, Wiemels JL. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:867–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smrdel U, Kovac V, Popovic M, Zwitter M. Glioblastoma patients in Slovenia from 1997 to 2008. Radiol Oncol. 2014;48:72–9. doi: 10.2478/raon-2014-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zakelj MP, Zadnik V, Zagar T, Zakotnik B. Survival of cancer patients, diagnosed in 1991–2005 in Slovenia. Ljubljana: Institute of Oncology Ljubljana, Epidemiology and Cancer Registry, Cancer Registry of Republic of Slovenia; 2009. p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neurooncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.20069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podergajs N, Brekka N, Radlwimmer B, Herold-Mende C, Talasila KM, Tiemann K, et al. Expansive growth of two glioblastoma stem-like cell lines is mediated by bFGF and not by EGF. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:330–7. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stupp R, Mason PW, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupp R, Hegi EM, Mason PW, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn JBM, Janzer CR, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsao MN, Mehta MP, Whelan TJ, Morris DE, Hayman JA, Flickinger JC, et al. The American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) evidence-based review of the role of radiosurgery for malignant glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blamek S, Larysz D, Miszczyk L, Idasiak A, Rudnik A, Tarnawski R. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for large or involving critical organs cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:50–6. doi: 10.2478/v10019-012-0046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Combs SE, Thilmann C, Edler L, Debus J, Schulz-Ertner D. Efficacy of fractionated stereotactic reirradiation in recurrent gliomas: long-term results in 172 patients treated in a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8863–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong DS, Lee JI, Park K, Kim JH, Lim DH, Nam DH. Efficacy of stereotactic radiosurgery as a salvage treatment for recurrent malignant gliomas. Cancer. 2008;112:2046–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yung WK, Prados MD, Yaya-Tur R, Rosenfeld SS, Brada M, Friedman HS, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma at first relapse: Temodal Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2762–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2762. [Erratum in J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 3693.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong ET, Hess KR, Gleason MJ, Jaeckle KA, Kyritsis AP, Prados MD, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in recurrent glioma patients enrolled onto phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2572–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yung WK, Albright RE, Olson J, Fredericks R, Fink K, Prados MD, et al. A phase II study of temozolomide vs. procarbazine in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:588–93. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Amistà P, Nicolardi L, Grosso D, Berti F, Ermani M. How effective is BCNU in recurrent glioblastoma in the modern era? A phase II trial. Neurology. 2004;63:1281–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140495.33615.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt F, Fischer J, Herrlinger U, Dietz K, Dichgans J, Weller M. PCV chemo-therapy for recurrent glioblastoma. Neurology. 2006;66:587–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197792.73656.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loscalzo J, Kohane I, Barabasi AL. Human disease classification in the post-genomic era: a complex systems approach to human pathobiology. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:124. doi: 10.1038/msb4100163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, Stroud I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:740–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cloughesy T, Vredenburgh JJ, Day B, Das A, Friedman HS. Updated safety and survival of patients with relapsed glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab in the BRAIN study. [Abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl 15) No. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen W, Delaloye S, Silverman DH, Geist C, Czernin J, Sayre J, et al. Predicting treatment response of malignant gliomas to bevacizumab and irinotecan by imaging proliferation with [18F] fluorothymidine positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4714–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins AHJE, Marcello J, Reardon DA, Quinn JA, Rich JN, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokstein F, Shpigel S, Blumenthal DT. Treatment with bevacizumab and irinotecan for recurrent high-grade glial tumors. Cancer. 2008;112:2267–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guiu S, Taillibert S, Chinot O, Taillandier L, Honnorat J, Dietrich PY, et al. [Bevacizumab/irinotecan. An active treatment for recurrent high grade gliomas: preliminary results of an ANOCEF Multicenter Study]. [French] Rev Neurol (Paris) 2008;164:588–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali SA, McHayleh WM, Ahmad A, Sehgal R, Braffet M, Rahman M, et al. Bevacizumab and irinotecan therapy in glioblastoma multiforme: a series of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:268–72. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/8/0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desjardins A, Reardon DA, Herndon JE, Marcello J, Quinn JA, Rich JN, et al. Bevacizumab Plus Irinotecan in Recurrent WHO Grade 3 Malignant Gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7068–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang TY, Jin T, Elinzano H, Peereboom D. Irinotecan and bevacizumab in progressive primary brain tumors, an evaluation of efficacy and safety. J Neurooncol. 2008;89:113–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulsen HS, Grunnet K, Sorensen M, Olsen P, Hasselbalch B, Nelausen K, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in the treatment patients with progressive recurrent malignant brain tumours. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:52–8. doi: 10.1080/02841860802537924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuniga RM, Torcuator R, Jain R, Anderson J, Doyle T, Ellika S, et al. Efficacy, safety and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:329–36. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. NCCN clinical practical guidelines in oncology. Central nervous system cancer. Version 2.2013. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed on 4 November 2013.

- 34.Stupp R, Tonn JC, Brada M, Pentheroudakis G. High grade malignant glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v190–3. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu T, Chen J, Lu Y, Wolff JEA. Effectstof bevacizumab plus irinotecan on response and survival in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a systematic review and survival-gain analysis. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]