Abstract

Objectives

To characterize health status outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with a self-expanding bioprosthesis among patients at extreme surgical risk and to identify pre-procedural patient characteristics associated with a poor outcome.

Background

For many patients considering TAVR, improvement in quality of life may be of even greater importance than prolonged survival.

Methods

Patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis who were considered to be at prohibitive risk for surgical aortic valve replacement were enrolled in the single-arm CoreValve U.S. Extreme Risk Study. Health status was assessed at baseline and at 1, 6, and 12 months after TAVR using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), the Short-Form-12 (SF-12), and the EuroQol-5D. The overall summary scale of the KCCQ (range 0-100; higher scores = better health) was the primary health status outcome. A poor outcome after TAVR was defined as either death, a KCCQ-overall summary score (KCCQ-OS) <45 or a decline in KCCQ-OS of 10 points at 6-month follow-up.

Results

A total of 471 patients underwent TAVR via the transfemoral approach, of whom 436 (93%) completed the baseline health status survey. All health status measures demonstrated considerable impairment at baseline. After TAVR, there was substantial improvement in both disease-specific and generic health status measures, with an increase in the KCCQ-OS of 23.9 points (95% confidence interval [CI] 20.3-27.5) at 1 month, 27.4 points (95% CI 24.2-30.6) at 6 months, 27.4 points (95% CI 24.1-30.8) at 12 months, along with substantial increases in SF-12 scores and EQ-5D utilities as well (all p<0.003 compared with baseline). Nonetheless, 39% of patients had a poor outcome after TAVR. Baseline factors independently associated with poor outcome included wheelchair dependency, lower mean aortic valve gradient, prior CABG, oxygen dependency, very high predicted mortality with surgical AVR, and low serum albumin.

Conclusions

Among patients with severe aortic stenosis, TAVR with a self-expanding bioprosthesis resulted in substantial improvements in both disease-specific and generic health-related quality of life, but there remained a large minority of patients who died or had very poor quality of life despite TAVR. Predictive models based on a combination of clinical factors as well as disability and frailty may provide insight into the optimal patient population for which TAVR is beneficial.

Keywords: Aortic stenosis, heart valves, quality of life, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Aortic stenosis is the most common form of valvular heart disease in the elderly and is associated with high morbidity and mortality once cardiac symptoms develop (1). In patients who are at extreme risk for serious complications during or after surgery, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has been shown to result in substantial reductions in mortality and improvement in quality of life compared with standard therapy (2,3). Despite these health benefits, extreme risk patients who undergo TAVR have high rates of both short- and long-term mortality, with mortality rates of 30% and 43% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (2,4). Moreover, given the advanced age and multiple comorbid conditions that are invariably present in the extreme risk population, improvements in quality of life may be of even greater importance than improved survival.

The CoreValve transcatheter heart valve (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) is a self-expanding bioprosthesis that is widely used outside the U.S. In a recently completed trial, the CoreValve was shown to be safe and effective for patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgical valve replacement (5), but the quality of life benefits of this device are unknown. To address this gap in knowledge, we sought to characterize health status outcomes among patients at extreme surgical risk who were enrolled in the CoreValve U.S. Pivotal Trial. Our secondary objective was to identify pre-procedural patient characteristics (including comorbidities, surgical risk scores, and measures of frailty and disability) associated with a poor outcome after self-expanding TAVR.

METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

The design and results of the CoreValve U.S. Extreme Risk Pivotal Trial have been reported previously (5). Briefly, the trial enrolled patients with severe aortic stenosis and New York Heart Association class II, III or IV heart failure symptoms. Patients were classified as extreme risk if the 30-day risk of mortality or irreversible morbidity was estimated to be ≥50% by 2 cardiac surgeons and 1 interventional cardiologist (5). In the screening process, each patient was reviewed in detail by a national screening committee that included at least 2 cardiac surgeons and 1 interventional cardiologist, each of whom had to agree that the patient met eligibility, risk, and imaging criteria for the trial. After confirmation by the trial oversight committee, patients underwent TAVR via an iliofemoral approach, using the Medtronic self-expanding CoreValve system (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Health Status Assessment

Disease-specific and generic health status were assessed at baseline, and at 1, 6 and 12 months after enrollment using written questionnaires. Questionnaires were administered either during in-person visits to the study sites or by mail. Disease-specific health status was assessed with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a 23-item self-administered questionnaire that assesses specific health domains pertaining to heart failure: symptoms, physical limitation, social limitation, self-efficacy, and quality of life (6). The individual domains can be combined into an overall summary score (KCCQ-OS), which was the pre-specified primary endpoint for this study. Values for all KCCQ domains and the summary score range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less symptom burden and better quality of life. Prior studies have shown that the KCCQ-OS generally correlates with New York Heart Association functional class as follows: Class I: KCCQ-OS 75 to 100; Class II: 60 to 74; Class III: 45 to 59; Class IV: 0 to 44 (7,8). Changes in the KCCQ-OS of 5, 10, and 20 points correspond to small, moderate or large clinical improvements, respectively (7). The KCCQ has been shown to be a reliable, responsive and valid measure of symptoms, functional status and quality of life among a variety of patients with heart failure symptoms, including those with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (8).

Generic health status was evaluated with the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 12 (SF-12) questionnaire (9) and the EuroQol (EQ-5D) (10). Derived from the Short-Form 36, the SF-12 provides mental and physical summary scores that are scaled to overall US norms of 50 with standard deviations of 10. Higher scores indicate better quality of life, and the minimum clinically important difference for the SF-12 summary scores is 2 to 2.5 points (11). The EQ-5D is a generic health status measure consisting of 5 domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), which can be converted to utilities using an algorithm developed for the U.S. population (12). Utilities are preference-weighted health status assessments with scores that range from 0 to 1, with 1 representing perfect health and 0 corresponding to the worst imaginable health state (13).

Statistical Analysis

At each follow-up time-point, scores for each of the disease-specific and generic health status scores were compared with baseline values using paired t-tests. At each time-point, the baseline value comparator consisted of only those patients that had a quality of life assessment performed at that time-point, thereby addressing survivor bias caused by attrition of sicker patients over time.

To provide additional insight into the changes in health status over time, we also performed several categorical analyses. First, among the survivors at each time-point, we calculated the proportion of patients who had a moderate (≥10 points) or large (≥20 points) improvement in the KCCQ-OS compared with baseline. Second, we calculated the proportion of enrolled patients at each time-point with favorable and excellent outcomes, defined as being both alive and having a moderate or large improvement, respectively, in the KCCQ-OS compared with baseline. For these latter metrics, death was considered to be the same as failure to improve by the specified amount. The 95% confidence interval for proportion was based on the binomial distribution.

Finally, we calculated the proportion of patients with a poor outcome at 6 months after TAVR. For this analysis, a poor outcome was defined as any of the following at 6 months after TAVR: (1) death; (2) KCCQ-OS <45; or (3) decrease of ≥10 points on the KCCQ-OS from baseline (14). We then used multivariable logistic regression to identify pre-procedural factors associated with poor 6-month outcome. Candidate variables for this analysis are listed in eTable 1. We used stepwise selection to identify variables associated with poor outcome at a significance level of p≤0.10, and then refit the model with the identified variables. The baseline score on the KCCQ-OS was forced into the model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A 2-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant with no correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Patient Population

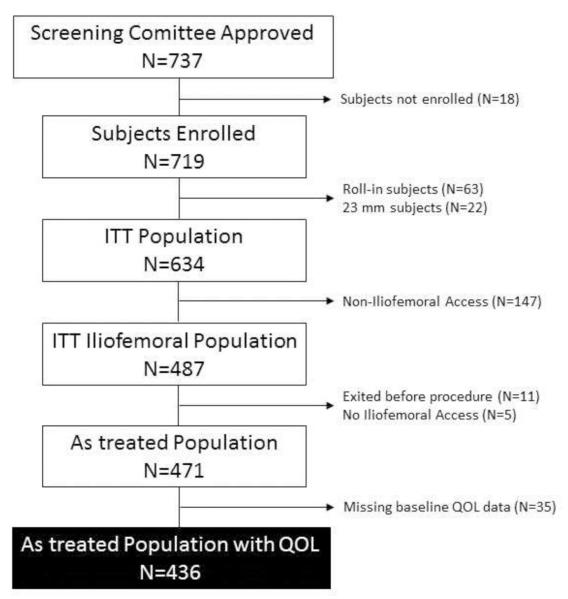

Between February 2011 and August 2012, 737 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis at extreme surgical risk from 41 U.S. sites were approved by the trial screening committee for inclusion in the CoreValve U.S. Extreme Risk Study. Of these, 18 were not enrolled (due to withdrawal by the patient or treating physician), 85 were roll-in patients or were treated in a separate registry with the 23 mm CoreValve, and 147 were planned for noniliofemoral access, leaving 487 patients in the intention-to-treat population. Sixteen patients subsequently did not undergo iliofemoral TAVR, and an additional 35 did not have baseline health status data. With the exception of being somewhat younger, patients with missing baseline health status assessments were generally similar to those patients with complete baseline data (eTable 2). As such, the analytic population for our study included 436 patients who underwent iliofemoral TAVR and had baseline health status assessment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient Flow Chart.

Consort diagram showing patient flow for the CoreValve U.S. Pivotal trial. The black box indicates the primary analytic population for this quality of life study.

The baseline characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 84 years, and 49% were male. The mean aortic valve gradient was 48 mmHg, and 92% were classified as NYHA Class III-IV. The patients had a high burden of chronic medical conditions, including 30% who were on home oxygen and 16% who were wheelchair bound. Both disease-specific and generic health status measures demonstrated substantial impairment at baseline. The mean KCCQ-OS score was 37.9 ± 22.2 (roughly comparable to New York Heart Association Class IV); the mean SF-12 physical summary score was 28.5 ± 8.3 (~2 SD below the standard for the general U.S. population); the mean SF-12 mental summary score was 45.8 ± 12.3; and the mean baseline EQ-5D score was 0.65 ± 0.24.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the CoreValve Extreme Risk Cohort

| “As Treated” Population n=436 |

|

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |

| Age, y | 84.0 ± 8.5 |

| Male | 49.1% (214/436) |

| White Race | 95.6% (417/436) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 28.6 ± 7.0 |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| STS Risk Score | 10.4 ± 5.6 |

| STS: <5 | 12.6% (55/436) |

| STS: 5 - <10 | 42.7% (186/436) |

| STS: 10 - <15 | 26.1% (114/436) |

| STS: ≥15 | 18.6% (81/436) |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 22.8 ± 17.7 |

| NYHA Class | |

| II | 8.3% (36/434) |

| III | 65.0% (282/434) |

| IV | 26.7% (116/434) |

| Prior MI | 31.7% (138/436) |

| Prior CABG | 40.6% (177/436) |

| Prior Stroke | 13.8% (60/436) |

| Home Oxygen | 29.8% (130/436) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 13.2% (57/431) |

| Mean Aortic Valve Gradient, mmHg | 47.6 ± 14.8 |

| Frailty and Disability Measures | |

| Albumin <3.3 g/dl | 17.6% (75/427) |

| Wheelchair Bound | 15.8% (69/436) |

| 6-Minute Walk Distance, meters | 167.5 ± 117 |

| 5-Meter Gait Speed > 6 seconds | 84.5% (262/310) |

| Low Grip Strength* | 65.7% (286/435) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| Mild (1-2) | 8.7% (38/436) |

| Moderate (3-4) | 32.8% (143/436) |

| Severe (5) | 58.5% (255/436) |

| Quality-of-Life Measures | |

| KCCQ overall summary | 37.9 ± 22.2 |

| 75-100, % | 7.1% (31/436) |

| 60-74, % | 9.6% (42/436) |

| 45-59, % | 18.8% (82/436) |

| 0-45, % | 64.4% (281/436) |

| KCCQ symptoms | 48.1 ± 24.2 |

| KCCQ physical limitation | 35.3 ± 24.9 |

| KCCQ social limitation | 30.5 ± 28.4 |

| KCCQ quality-of-life | 36.3 ± 24.5 |

| SF-12 physical summary score | 28.5 ± 8.3 |

| SF-12 mental summary score | 45.8 ± 12.3 |

| EQ-5D | 0.65 ± 0.24 |

EQ-5D, European Quality of Life Group instrument-5 dimensions; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire;; NYHA, New York Heart Association; MI, myocardial infarction; SF-12, Short Form-12 General Health Survey; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; QOL, quality-of-life.

defined according to the thresholds proposed by Luna-Heredia et al.(24)

Follow-up Health Status

Follow-up health status data were available for 58% of surviving patients at 1 month, 74% at 6 months, and 77% at 12 months after TAVR. Mean scores and the mean changes from baseline at each follow-up time-point are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. On average, KCCQ-OS scores increased by 23.9 points at 1 month and 27.4 points at 6 and 12 months after TAVR compared with baseline (P<0.001 for all comparisons). The individual KCCQ subscales showed similar patterns (Table 2, Figure 2). The SF-12 physical and mental summary scores improved by ~5 points at 6 and 12 months compared with baseline, and EQ-5D utility values also increased substantially at all time-points as well (P<0.003 for all comparisons; Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 2.

Mean Follow-up Scores and Changes in Disease-Specific and Generic Health Status Measures Compared with Baseline

| Scale/Time Point | Mean (±SD) Value |

Mean Δ vs Baseline |

95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCCQ summary | ||||

| 1 month | 62.0 ± 25.8 | 23.9 | (20.3, 27.5) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 67.6 ± 24.2 | 27.4 | (24.2, 30.6) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 68.5 ± 23.6 | 27.4 | (24.1, 30.8) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ total symptoms | ||||

| 1 month | 69.0 ± 23.8 | 22.1 | (18.6, 25.7) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 73.6 ± 23.1 | 23.0 | (19.8, 26.2) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 74.2 ± 21.4 | 22.8 | (19.5, 26.1) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ physical limitations | ||||

| 1 month | 53.2 ± 30.7 | 16.5 | ( 12.0, 21.0) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 57.5 ± 28.7 | 19.4 | ( 15.5, 23.3) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 53.7 ± 28.6 | 14.1 | ( 9.9, 18.2) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ social limitation | ||||

| 1 month | 58.5 ± 33.7 | 24.8 | ( 19.6, 29.9) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 63.8 ± 31.2 | 27.2 | ( 22.4, 32.1) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 64.7 ± 31.0 | 29.1 | ( 23.8, 34.4) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ quality of life | ||||

| 1 month | 64.7 ± 28.1 | 28.9 | (24.7, 33.0) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 72.0 ± 26.7 | 33.7 | (30.0, 37.4) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 74.8 ± 25.0 | 36.3 | (32.5, 40.1) | <0.001 |

| SF-12 physical | ||||

| 1 month | 35.0 ± 10.2 | 5.8 | (4.4, 7.2) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 33.6 ± 11.3 | 5.0 | (3.5, 6.4) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 34.1 ± 10.6 | 5.1 | (3.7, 6.5) | <0.001 |

| SF-12 mental | ||||

| 1 month | 49.7 ± 12.3 | 3.9 | (1.9, 5.8) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 51.4 ± 11.1 | 4.5 | (2.7, 6.3) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 51.7 ± 11.8 | 5.1 | (3.3, 7.0) | <0.001 |

| EQ-5D utility | ||||

| 1 month | 0.726 ± 0.238 | 0.084 | (0.047, 0.121) | <0.001 |

| 6 months | 0.757 ± 0.202 | 0.092 | (0.065, 0.120) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 0.727 ± 0.208 | 0.058 | (0.027, 0.090) | 0.003 |

CI indicates confidence interval; EQ-5D KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; and SF-12, Short-Form-12 General Health Survey.

P value derived from paired t tests comparing follow-up score and baseline.

Figure 2. Disease-specific Health Status after TAVR.

Changes in disease-specific health status according to the KCCQ overall summary scale (panel A) and subscales (panels B-E) at 1, 6, and 12 months after TAVR. Baseline values indicated by the dashed line correspond to the evaluable patient population at each time point. Mean values and p-values are derived from paired t-tests comparing each patient with his or her own baseline value.

Figure 3. Generic Health Status After TAVR.

Changes in generic health status according to the SF-12 and EQ-5D at 1, 6, and 12 months after TAVR. Baseline values indicated by the dashed line correspond to the evaluable patient population at each time point. Mean values and p-values are derived from paired t-tests comparing each patient with his or her own baseline value.

Categorical Analyses

The rates of moderate and large improvements in KCCQ-OS and favorable and excellent outcomes at each time-point are shown in Table 3. Among responders to the surveys, the proportion of patients with large KCCQ-OS improvements was 58% at 1 month and 59% at 12 months after TAVR. The proportion of treated patients with an excellent outcome (i.e., alive with a large improvement in KCCQ-OS) was 52% at 1 month and 41% at 12 months after TAVR.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients with clinically important improvement in the KCCQ summary score

| Population and Level of Benefit | Proportion (95% CI) [n/N] |

|---|---|

| Among responders to the survey | |

| Moderate improvement (≥10-point increase from baseline) | |

| 1 month | 70.0% (63.9, 75.6) [175/250] |

| 6 months | 71.1% (65.3, 76.4) [192/270] |

| 12 months | 71.3% (65.3, 76.7) [181/254] |

| Large improvement (≥20-point increase from baseline) | |

| 1 month | 58.0% (51.6, 64.2) [145/250] |

| 6 months | 61.1% (55.0, 67.0) [165/270] |

| 12 months | 59.1% (52.7, 65.1) [150/254] |

| Among all treated patients* | |

| Favorable outcome (alive with ≥10-point increase from baseline)* | |

| 1 month | 62.3% (56.3, 68.0) [175/281] |

| 6 months | 54.9% (49.5, 60.1) [192/350] |

| 12 months | 49.5% (44.2, 54.7) [181/366] |

| Excellent outcome (alive with ≥20-point increase from baseline)* | |

| 1 month | 51.6% (45.6, 57.6) [145/281] |

| 6 months | 47.1% (41.8, 52.5) [165/350] |

| 12 months | 41.0% (35.9, 46.2) [150/366] |

Denominator includes patients who died but excludes patients who voluntarily withdrew from the study before the time point. KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Factors Associated with Poor Outcome

The proportion of patients with a poor outcome was 39% at 6 months (22% death, 16% very poor quality of life, and 1.4% quality of life decline). Pre-procedural factors that were independently associated with a poor outcome are shown in Table 4. Patients who were wheelchair-bound were 2.6 times more likely to have a poor outcome after TAVR, compared with patients who were able to ambulate (95% CI, 1.3-5.2). In addition, having a lower aortic valve gradient, previous CABG, and requiring home oxygen were strongly associated with a poor outcome. The association between the STS risk score (i.e., the predicted risk of operative mortality with surgical AVR) and a poor outcome of TAVR was only significant for an STS mortality risk >15%. When patients were compared according to whether they met VARC criteria for procedural success (15), those patients who achieved procedural success had greater improvements in health status (mainly at the 1 month time point) and were more likely to experience favorable or excellent outcomes at all timepoints (eTables 3 and 4). After adjusting for those pre-procedure factors summarized in Table 4, procedural success was inversely associated with a poor outcome after TAVR (adjusted odds ratio 0.40, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Predictors of Poor Outcome*

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline KCCQ overall score | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 0.488 |

| Prior CABG | 1.9 (1.2, 3.3) | 0.011 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient (per 10 mmHg)** | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.007 |

| STS Score*** | 0.052 | |

| STS 10-15 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.2) | |

| STS ≥15 | 2.0 (1.1, 3.7) | |

| Home oxygen | 1.7 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.044 |

| Albumin <3.3 g/dl | 1.8 (0.9, 3.5) | 0.073 |

| Wheelchair Bound | 2.6 (1.3, 5.2) | 0.006 |

Poor outcome defined as 1) Death within 6 months; (2) KCCQ-OS < 45; or KCCQ-OS decrease more than 10 points vs. baseline.

Resting gradient

Reference category is STS mortality risk score <10

Model C-statistic = 0.72

DISCUSSION

The CoreValve U.S. Extreme Risk Study has demonstrated that TAVR using a self-expanding bioprosthesis is safe and effective in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis at prohibitive risk for surgical replacement (5). In this pre-specified quality of life sub-study, we found that among patients at prohibitive risk of surgical complications, treatment with the CoreValve device via a transfemoral approach leads to substantial improvement in disease-specific and general health status.. These benefits were evident by 1 month after TAVR and were followed by modest additional improvement through 12 months. In addition, we identified several factors, including comorbid conditions, disability/frailty, and valve physiology, that were independently associated with poor outcomes after TAVR—a finding which, if replicated in future studies, may help to inform clinical decision-making in patients considering TAVR.

We observed substantial improvements in both disease-specific and generic health status measures after TAVR. Among surviving patients, the mean improvements in the KCCQ-OS scale were >20 points at all follow-up time-points; in previous studies, a 5-point change in this scale has been found to be clinically meaningful and also correlates with important differences in survival and health care costs (16,17). Furthermore, we observed increases in SF-12 physical and mental component scores of ~5 points. This increment represents twice the minimum clinically important difference for an individual patient (11) and is roughly comparable to reversing 10 years of normal decline in health in the general population (18).

Previous studies have also reported substantial improvements in health status after surgical AVR (19,20) and TAVR (3,21-23). However, most of these studies have only examined changes in generic health status. To date, only one other multicenter trial, the Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve (PARTNER) trial, has rigorously evaluated disease-specific health status after TAVR (3,23). In PARTNER Cohort B, which included patients who were considered surgically inoperable (i.e. similar to the CoreValve Extreme Risk U.S, trial), TAVR resulted in substantial improvement in both disease-specific and generic health status. Although cross-trial extrapolation should be considered purely exploratory, the health status outcomes observed in the CoreValve Extreme Risk and PARTNER B trials were roughly comparable with respect to both disease-specific and generic health status measures through the first year of follow-up (eTable 5). The current study thus confirms that the health status benefits of TAVR are not restricted solely to balloon-expandable transcatheter valves but also apply to the CoreValve self-expanding transcatheter valve.

Although many patients have excellent outcomes after TAVR, we also found that nearly 40% of patients did not experience meaningful improvements in survival or functional status at 6 months after TAVR. We identified preoperative factors that are associated with poor outcomes, which included measures of disability and frailty (e.g., wheelchair dependency, low serum albumin), comorbidity (prior CABG, extremely high predicted surgical mortality, oxygen dependency) and valve physiology (mean aortic valve gradient). Compared with prior work investigating predictors of poor outcome after TAVR in the PARTNER population (both inoperable and high risk patients) we found some similar predictors (e.g. poor functional status, oxygen dependence, low aortic valve gradient) and some novel predictors (e.g. low albumin, prior bypass surgery) in the CoreValve population (14). Further work is needed to establish a model that can be applied across all TAVR patients, regardless of valve type and surgical risk, such that patients at high-risk for poor outcomes may be identified prospectively. In the future, this information could be invaluable to both patients and physicians, to help them decide whether or not to undergo TAVR and also to set realistic expectations for recovery.

Our study has several potential limitations. First and foremost, the CoreValve U.S. Extreme Risk Study was a single-arm trial, and as such, there was no control arm to which the results of TAVR could be compared. Originally, the study design intended to randomize patients CoreValve implantation vs. medical therapy. However, after publication of the results from Cohort B of the PARTNER trial (2), the investigators and the FDA felt that it was no longer ethical to randomize these patients to standard therapy. Consequently, we were limited to comparing health status after TAVR with each patient’s individual baseline. Of note, the control arm of the PARTNER B trial, which enrolled a similar patient population, demonstrated modest short-term improvements in health status (most likely attributable to the high rate of balloon aortic valvuloplasty) that were not sustained at 1-year (3). Second, the proportion of patients with missing quality of life data increased modestly over time due to both mortality and non-response among surviving patients. To address this issue, we also reported categorical outcome variables that included all treated patients (as opposed to responding patients; i.e., excellent outcome), thereby treating patients with missing data (including death) as ‘treatment failures’. If sicker patients were less likely to respond, we may have overestimated the extent of clinical benefit. Third, our study was restricted to the iliofemoral cohort of the CoreValve extreme risk trial and included only 12 months of follow-up. Thus, the durability of the observed health status improvements, as well as the health status improvement after non-iliofemoral procedures remain unknown.

Conclusions

In patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who are at extreme risk of surgical complications, TAVR using the CoreValve self-expanding aortic bioprosthesis via a transfemoral approach resulted in large improvements in both disease-specific and generic health status measures in the majority of surviving patients. Nonetheless, similar to prior studies with a balloon expandable transcatheter valve, there remains a substantial minority of patients who do not derive a meaningful survival or quality of life benefit from TAVR. A combination of pre-procedural clinical, frailty, disability. and physiologic factors may provide further insight into identifying patients at high-risk for poor outcomes.

Supplementary Material

eTable 1. Variables considered for the multivariable logistic regression model.

eTable 2. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics among Patients with or without Baseline Health Status Data

eTable 3. Mean Follow-up Scores and Changes in Health Status Compared with Baseline, Stratified According to Procedural Success

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients with Clinically Important Improvement in the KCCQ Overall Summary Score According to Procedural Success

eTable 5. Comparison of 12-month Health Status Outcomes between the CoreValve Extreme Risk and PARTNER B Trials

CONDENSED ABSTRACT.

For many patients considerting transcatheter aortic valve replacement, improvement in quality of life may be of even greater importance than prolonged survival. In this single-arm trial, TAVR via the transfemoral approach with a self-expanding bioprosthesis resulted in substantial improvements in both disease-specific and generic health-related quality of life, but there remained a substantial minority of patients who died or had very poor quality of life despite TAVR. Predictive models based on a combination of clinical factors as well as disability and frailty may provide insight into the optimal patient population for which TAVR is beneficial.

Acknowledgements

Dr Cohen has received grant support from Abbott Vascular, Astra Zeneca, Biomet, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Eli Lilly, Jannsen Pharmaceuticals and Medtronic, and consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Medtronic. Dr. Magnuson has received grant support from Abbott Vascular, Astra Zeneca, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Eli Lilly and Medtronic. Dr. Reynolds has received consulting fees from Medtronic. Dr. Stoler serves in medical advisory boards for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Kleiman reports receiving fees through his institution from Medtronic for didactic training sessions; Dr. Reardon reports receiving honoraria from Medtronic for participation on a surgical advisory board; Dr. Adams reports receiving royalties through his institution from Medtronic for a patent related to a triscupid-valve annuloplasty ring and from Edwards Lifesciences for a patent related to degenerative valvular disease–specific annuloplasty rings; Dr. Popma reports receiving honoraria from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, and St. Jude Medical for participation on medical advisory boards.

Funding/Support: Funded by Medtronic

Role of the Sponsors: The industry sponsors reviewed the study design and were involved in data management for the CoreValve U.S. Pivotal trial. The sponsor had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data or in the preparation of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AVR

aortic valve replacement

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

confidence interval

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- EQ-5D

EuroQol

- SF-12

Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 12

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Footnotes

Clinical trial unique identifier: NCT01240902 (clinical-trials.gov)

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All other co-authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Additional Contributions: We thank Holly Vitense and Jane Moore for her administrative assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e1–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Lei Y, et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011;124:1964–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1696–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Using A Self-Expanding Bioprosthesis in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis at Extreme Risk for Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014:1972–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, et al. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: a comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150:707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Lei Y, et al. Use of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire for Monitoring Health Status in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:61–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.970053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware J, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowkes DM, Gandek B, Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. QualityMetric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI: 2007. Determining important differences in scores. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43:203–20. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold SV, Reynolds MR, Lei Y, et al. Predictors of Poor Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Results from the PARTNER Trial. Circulation. 2014:2682–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized endpoint definitions for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation clinical trials: a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:253–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan PS, Soto G, Jones PG, et al. Patient health status and costs in heart failure: insights from the eplerenone post-acute myocardial infarction heart failure efficacy and survival study (EPHESUS) Circulation. 2009;119:398–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.820472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto GE, Jones P, Weintraub WS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110:546–51. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136991.85540.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowkes DM, Gandek B. How to score version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement documenting version 1) Quality Metric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan JH, McElhinney DB, Hall TS, Merrick SH. Cardiac valve surgery in octogenarians: improving quality of life and functional status. Arch Surg. 1998;133:887–93. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.8.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundt TM, Bailey MS, Moon MR, et al. Quality of life after aortic valve replacement at the age of >80 years. Circulation. 2000;102:Iii70–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairbairn TA, Meads DM, Mather AN, et al. Serial change in health-related quality of life over 1 year after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: predictors of health outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1672–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimaldi A, Figini F, Maisano F, et al. Clinical outcome and quality of life in octogenarians following transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for symptomatic aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Wang K, et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) Trial (Cohort A) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:548–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luna-Heredia E, Martin-Pena G, Ruiz-Galiana J. Handgrip dynamometry in healthy adults. Clin Nutr. 2005;24:250–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Variables considered for the multivariable logistic regression model.

eTable 2. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics among Patients with or without Baseline Health Status Data

eTable 3. Mean Follow-up Scores and Changes in Health Status Compared with Baseline, Stratified According to Procedural Success

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients with Clinically Important Improvement in the KCCQ Overall Summary Score According to Procedural Success

eTable 5. Comparison of 12-month Health Status Outcomes between the CoreValve Extreme Risk and PARTNER B Trials