Summary

Notch (N) signaling is used for cell fate determination in many different developmental contexts. Here we show that the master control gene for sex determination in Drosophila melanogaster, Sex-lethal (Sxl), negatively regulates the N signaling pathway in females. In genetic assays, reducing Sxl activity suppresses the phenotypic effects of N mutations while increasing Sxl activity enhances the effects. Sxl appears to negatively regulate the pathway by reducing N protein accumulation and higher levels of N are found in Sxl−clones than in adjacent wild type cells. The inhibition of N expression does not depend on the known downstream targets of Sxl; however we find that Sxl protein can bind to N mRNAs. Finally our results indicate that downregulation of the N pathway by Sxl contributes to sex specific differences in morphology and suggest that it may also play an important role in follicle cell specification during oogenesis.

Introduction

Sexual dimorphism in Drosophila melanogaster is controlled by an extensively characterized regulatory hierarchy (Cline and Meyer, l996). The choice of sexual identity is initially determined by the X chromosome to autosome ratio (X:A). Females (XX) have an X:A of 1 while males (XY) have an X:A of 0.5. In females the system that counts the X:A ratio turns on Sex-lethal (Sxl), the master switch gene for sex determination in the soma. Once activated, Sxl proteins maintain female identity through a positive autoregulatory feedback loop in which they promote their own synthesis by directing the female specific splicing of Sxl pre-mRNAs. Sxl also orchestrates female development by regulating gene cascades that control different aspects of sex-specific development. Sxl promotes female differentiation by directing the female specific splicing of transformer (tra). Tra together with the ubiquitously expressed splicing factor, transformer-2 (tra-2) activates female differentiation and behavior by promoting the female-specific splicing of the transcription factors doublesex (dsx) and fruitless (fru). Sxl also ensures the proper level of X-linked gene expression in females by repressing the translation of the male-specific lethal-2 (msl-2) mRNA. Conversely, in males where Sxl is off, tra transcripts are spliced in the non-productive male pattern. As a consequence, both dsx and fru transcripts are spliced to give male specific proteins that promote male differentiation and behavior. The msl-2 mRNA is also translated in the absence of Sxl, and the Msl-2 protein activates the X chromosome dosage compensation.

Many of the sex-specific differences in gene expression and morphology are under the control of dsx. The first genes found to be regulated by dsx were the yolk protein (yp) genes which are activated in females by DsxF and repressed in males by DsxM (Burtis et al., 1991). More recent experiments indicate that dsx regulates sexual dimorphism by sex-specifically modulating transcription factors and signaling pathways. For example, Dsx directs sexually dimorphic development of the genital disc by controlling the activity of the transcription factor dachshund and by differentially deploying the branchless (bnl)/FGF, wingless and decapentaplegic signaling pathways in the two sexes (Ahmad and Baker, 2002; Keisman and Baker, 2001; Sanchez et al., 2001).

While the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru regulatory cascade controls many aspects of sexual differentiation and behavior, there are some sexually dimorphic traits that are independent of this cascade. For example, adult D. melanogaster females are larger than males. Though this difference in size does not depend on tra, tra-2, dsx, or fru, it is determined by Sxl (Cline and Meyer, l996). Similarly, while the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru cascade is known to determine whether bristles are present or absent on sternites A6 and A7 (Kopp et al., 2000), it is unknown whether this cascade also controls the sexually dimorphic difference in bristle number on sternite A5 (Kopp et al., 2003). Given that dsx directs sex-specific differentiation by modulating the activity of cell-cell signaling pathways, we reasoned that Sxl might use a similar strategy to specify sexually dimorphic traits that are independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru regulatory cascade. Consistent with this idea we show that Sxl negatively regulates the activity of the Notch (N) signaling pathway in several different developmental contexts. The mechanism of regulation does not depend upon the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru cascade, but rather is likely to involve the direct binding of Sxl protein to Notch mRNAs. Moreover, this regulation appears to play an important role in sex-specific differentiation.

Results

Packaging defects are observed in fl(2)d1 ovaries

To investigate the possibility that Sxl modulates the activity of signaling pathways by mechanisms that are independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru cascade, we first needed to circumvent the female lethal effects arising from upsets in dosage compensation when Sxl activity is lost. To selectively turn off Sxl we took advantage of a conditional allele of fl(2)d. While fl(2)d encodes a splicing factor that is required for viability in both sexes, the fl(2)d1 allele specifically compromises Sxl autoregulation (Granadino et al., 1992). This allele is temperature sensitive and at 18° C a few homozygous fl(2)d1 females survive to the adult stage. Thus it is possible to raise females at the permissive temperature and then turn off Sxl by a temperature shift. Second, we needed a developmental context to investigate the effects of losing Sxl activity. We selected oogenesis because it depends upon the action of multiple pathways that signal between germline and soma and within the soma itself.

To determine whether Sxl activity is lost after fl(2)d1 females raised at the permissive temperature are transferred to 29° C, we examined Sxl protein expression in fl(2)d1 ovaries. In wild type stage 1–11B egg chambers, Sxl is expressed in all somatic follicle cells and can be detected in the nuclei and cytoplasm. In the germline, Sxl is also found in nurse cell nuclei and cytoplasm, but is absent from the oocyte (Bopp et al., 1993; Fig 1A). A different pattern is evident in fl(2)d1. As illustrated in Fig 1B the follicle cells in fl(2)d1 egg chambers are typically subdivided into two (or more) domains. Cells in one domain have high levels of Sxl, while Sxl is severely reduced or absent in cells in the other domain. This pattern of Sxl expression is consistent with a clonal inheritance of the Sxlon and Sxloff states in dividing follicle cells. The effects of fl(2)d1 in the germline are more uniform and in most cases the level of Sxl in the nurse cells is severely reduced (Fig 1B).

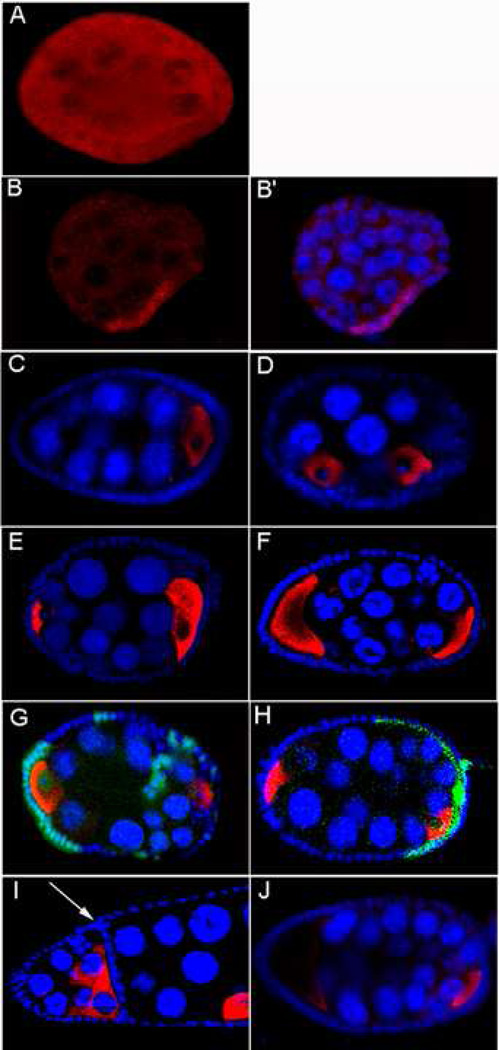

Figure 1. Loss of Sxl in follicle cells results in egg chamber packaging defects.

(A–B’) Whole mount ovaries labeled for Sxl (red) and Hoechst (blue):

(A) wt, (B, B’) Loss of Sxl protein in fl(2)d1/fl(2)d1 egg chamber.

(C–J) Whole mount ovaries labeled for Orb (red) and Hoechst (blue):

(C) wt egg chamber. Egg chamber packaging defects observed in ovaries compromised for Sxl: (D) fl(2)d1/fl(2)d1, (E) P{w+;otu::Sxl}, fl(2)d1/fl(2)d1, (F) snfJ210/ snfJ210; P{w+; otu::Sxl}/ P{w+; otu::Sxl}; P{w+; snf5mer}/ P{w+; snf5mer}, (G) Sxl7BO follicle cell clones,

(H) Sxl7BO follicle cell clones induced in hsp83-traF ovaries (clones marked by the absence of GFP (green) in (G) and (H)).

(I) Partitioned chamber from Nts1/Nts1 ovary; the arrow indicates the intervening wall of follicle cells. (J) Nintra follicle cell clones produce packaging defects.

In addition to defects in Sxl protein expression we noticed that there were abnormalities in the organization of the egg chambers. As can be seen from the DNA staining pattern in Fig 1B’, many fl(2)d1 chambers have more than the normal complement of 15 nurse cells and an oocyte. Extra nurse cells can arise because germ cells fail to exit mitosis after forming the 16 cell cyst and undergo an extra mitotic division, generating a chamber that has 31 nurse cells and 1 oocyte (Hawkins et al., 1996). Alternatively, extra nurse cells can result from packaging defects. Egg chambers are packaged in region 2b of the germarium. Somatic follicle cells surround the newly formed 16 cell cysts, and then pinch the cysts off into chambers (Spradling, 1993). Packaging defects can occur if follicle cells are unable to encapsulate a single 16 cell cyst or if interfollicular stalk cells fail to form and separate the cysts (Jackson et al., 1997). To determine if multiple 16 cell cysts are encapsulated into single egg chambers in fl(2)d1, we probed for the oocyte marker Orb. In wild type, there is only one Orb positive oocyte (Lantz et al., 1994; Fig 1C). In contrast, when extra nurse cells are present in fl(2)d1 chambers, they usually contain an extra mispositioned oocyte (Fig 1D). This finding suggests that extra nurse cells arise because of follicle cell packaging defects rather than from an extra round of mitosis.

Packaging defects are observed in snf and Sxl clones

The results described above raise two questions. The first is whether we are correct in thinking that the packaging defects can be attributed to the soma rather than the germline. The second is whether these defects arise because of the loss of Sxl activity in fl(2)d1 or whether they stem from some other function of fl(2)d. Several experimental approaches were used to address these questions.

In the first we rescued Sxl in the germline but not the soma of fl(2)d1 ovaries by driving Sxl expression from the germline specific otu promoter (P{w+; otu::Sxl}) (Hager and Cline, 1997). Although P{w+; otu::Sxl} restores Sxl expression in the germline, it does not rescue packaging defects (Fig 1E). We next examined ovaries of a hypomorphic mutation in the snf gene, snf5mer (Nagengast et al., 2003; Stitzinger et al., 1999). snf encodes a protein component of the U1 and U2 snRNPs and, like fl(2)d, is an essential cofactor for Sxl autoregulation. As shown in Fig 1F we also observed egg chamber packaging defects in snf5mer ovaries. With the caveat that fl(2)d and snf might share unknown regulatory targets besides Sxl, these findings suggest that the packaging defects arise from insufficient Sxl activity in follicle cells. To confirm this suggestion, a transgene, e22c-flp that expresses FLP in the follicular epithelium was used to generate Sxl− clones (Gupta and Schupbach, 2003). Fig 1G shows that, as predicted, chambers containing Sxl− follicle cell clones have multiple oocytes and extra nurse cells.

Egg Chamber Packaging Defects are independent of tra

Proper female differentiation depends upon the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru cascade. When Sxl is lost in the follicle cells this cascade will switch to the male mode and male dsx and fru transcription factors will be expressed. Hence one plausible explanation for the packaging defects is that they arise because DsxM (or FruM) cannot support the proper development of the follicular epithelium. If this is correct, it should be possible to rescue these defects by providing Tra via a Sxl independent mechanism. For this purpose we used a transgene (hsp83-traF) that expresses Tra protein under the control of a constitutive hsp83 promoter. Previous studies have shown that this transgene fully rescues tra− females and feminizes wild type males (Waterbury et al., 2000). Contrary to the expectations of the cascade switch hypothesis, packaging defects (Fig 1H) are still evident when Sxl− follicle cell clones are induced in hsp83-traF females. This finding indicates that the Sxl− packaging phenotypes are independent of tra.

Loss of Sxl in follicle cells results in gain of function N phenotypes

As the Notch (N) signaling pathway is known to play a critical role in the encapsulation of egg chambers by follicle cells (Bender et al., 1993; Jackson et al., 1997) we compared the packaging defects induced by the loss of Sxl with those produced by a N temperature sensitive allele, Nts1. In both cases two different classes of improperly packaged egg chambers are observed. The first is the “partitioned” compound chamber. This type of fused chamber contains two or more 16-cell cysts separated from each other by an intervening wall of follicle cells (Ruohola et al., 1991; Xu et al., 1992; Fig 1I). The partitioned chambers likely arise when interfollicular stalk cells fail to form in the germarium, resulting in the incomplete separation of 16 cell cysts. The second class is the “combined” compound egg chamber. Combined chambers lack an intervening follicle cell wall (see Fig 1D–H). These chambers likely develop when follicle cells are unable to fully encapsulate and separate individual 16 cell cysts. Interestingly, partitioned chambers were more frequent for Nts1 than combined chambers, while for Sxl−clones the combined class was most frequent.

In addition to being required for encapsulation of the16 cell cysts, N signaling is necessary for the determination of the pair of polar cells that mark the anterior and posterior ends of the egg chamber (Grammont and Irvine, 2001; Fig 2A). In the absence of N, polar cells are not formed and the polar cell marker FasIII cannot be detected. Conversely, expression of constitutively active N in follicle cells adjacent to the polar cells results in ectopic FasIII expression. When Sxl activity is lost either in fl(2)d1 (Fig 2B, C) or Sxl− clones (Fig 2D), we often find egg chambers that have more than two pairs of FasIII positive cells. In most cases the extra FasIII positive cells are found in improperly packaged egg chambers, and they typically occur as pairs. However, ectopic FasIII positive cells can occur as single cells and as clusters of several cells. In addition, we also observe otherwise normal 16 cell chambers that have more than two sets of FasIII positive cells. To confirm the polar cell identity of these FasIII positive cells, we examined Eyes Absent (Eya) expression as it should not be present in properly differentiated polar cells (Bai and Montell, 2002). As expected for polar cells, we found that ectopic FasIII positive cells did not express Eya (Fig 2E–E’’). Like the egg chamber packaging defects, the presence of extra FasIII positive cells could not be rescued by hsp83-traF and thus is also Sxl dependent but tra independent (Fig 2F).

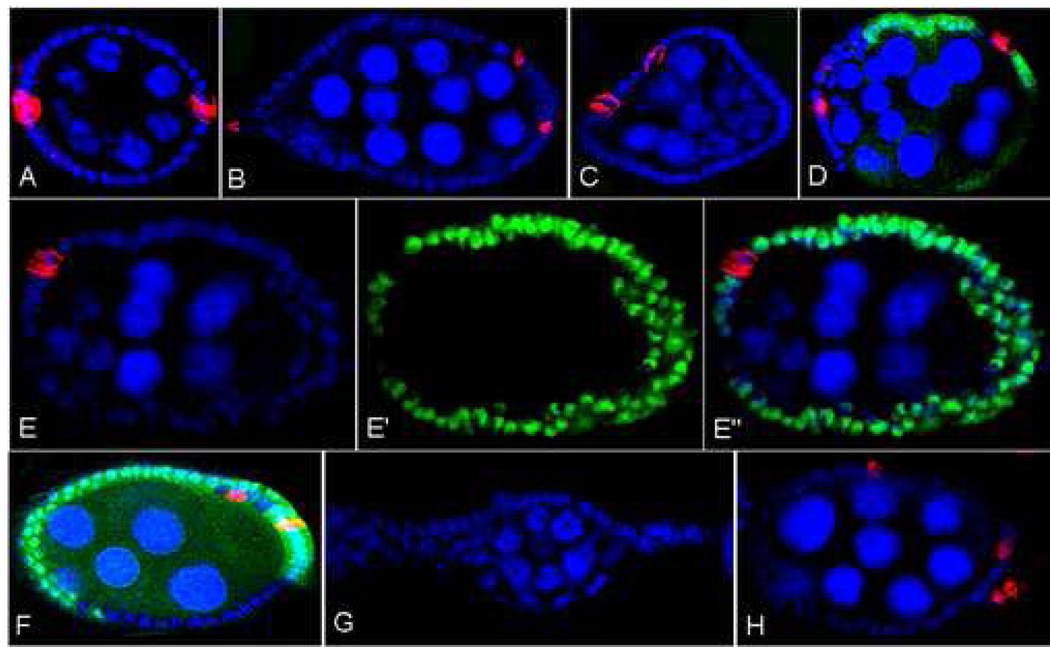

Figure 2. Loss of Sxl in follicle cells results in gain of function N phenotypes.

(A–D, F, H) Whole mount ovaries labeled for FasIII (red) and Hoechst (blue). Clones marked by the absence of GFP (green) in (D) and (F).

(A) wt egg chamber containing two pairs of FasIII expressing follicle cells at the anterior and posterior poles. Ectopic FasIII is expressed in main body follicle cells in egg chambers compromised for Sxl: (B) fl(2)d1/fl(2)d1, (C) P{w+; otu::Sxl}, fl(2)d1/fl(2)d1,

(D) Sxl7BO follicle cell clones.

(E–E’’) Whole mount ovaries labeled for FasIII (red), Eya (green), Hoechst (blue):

Main body follicle cells ectopically expressing FasIII upon induction of Sxl follicle cell clones (E, E’’) are likely ectopic polar cells as Eya is not expressed (E’,E’’).

(F) Main body follicle cells ectopically express FasIII upon induction of Sxl follicle cell clones in hsp83-traF ovaries.

(G) Larger interfollicular stalks form upon induction of Sxl follicle cell clones (Hoechst, blue).

(H) Nintra random follicle cell clones result in ectopic FasIII expression.

While these findings indicate that there is a connection between Sxl and N signaling in the follicular epithelium, the phenotypes observed, particularly the presence of extra polar cells in chambers containing Sxl− clones, would be more consistent with excess rather than too little N activity. This idea is supported by the effects of Sxl on interfollicular stalk formation. Stalk cells do not form when N activity is reduced, while oversized stalks are formed when there is excess N (Ruohola et al., 1992; Xu et al., 1992; Larkin et al., 1996). As expected for too much N activity, larger than normal stalks are formed in Sxl clones (Fig 2G).

Sxl suppresses N in the ovary

The abnormalities in the follicular epithelium evident when Sxl is lost point to a role for Sxl in modulating the N signaling pathway, most likely as a negative regulator. If both of these suggestions are correct, then reducing Sxl activity might ameliorate the effects of N mutations on follicular development. As described above, shifting Nts1 females to the non-permissive temperature disrupts oogenesis and 42% of the egg chambers (474/1126) have packaging defects. As would be expected if Sxl negatively regulates N, the frequency of packaging defects drops to 16% (280/1726) when the Nts1 females are heterozygous for the loss of function allele Sxl7B0.

N protein accumulation is upregulated in Sxl− follicle cell clones

Although Sxl could negatively regulate N signaling at many different points in the pathway, one attractive mechanism would be to control N protein accumulation. To investigate this possibility we examined N expression in Sxl− clones. In wild type ovaries, only low levels of N protein are observed after the onset of vitellogenesis (see stage 10B chamber in Fig 3A); however, when small Sxl− clones are induced in vitellogenic chambers high levels of N specifically accumulate in the Sxl− cells (Fig 3B, B’). The loss of Sxl activity in follicle cells of pre-vitellogenic chambers and in the germarium also results in the upregulation of N; however, because considerably higher amounts of N are present in follicle cells at these earlier stages, the differences between Sxl− and Sxl+ cells are not quite as striking as in later stages. This is shown for Sxl− clones in a pre-vitellogenic chamber in Fig 3D, D’ and in the germarium in Fig 3E, E’.

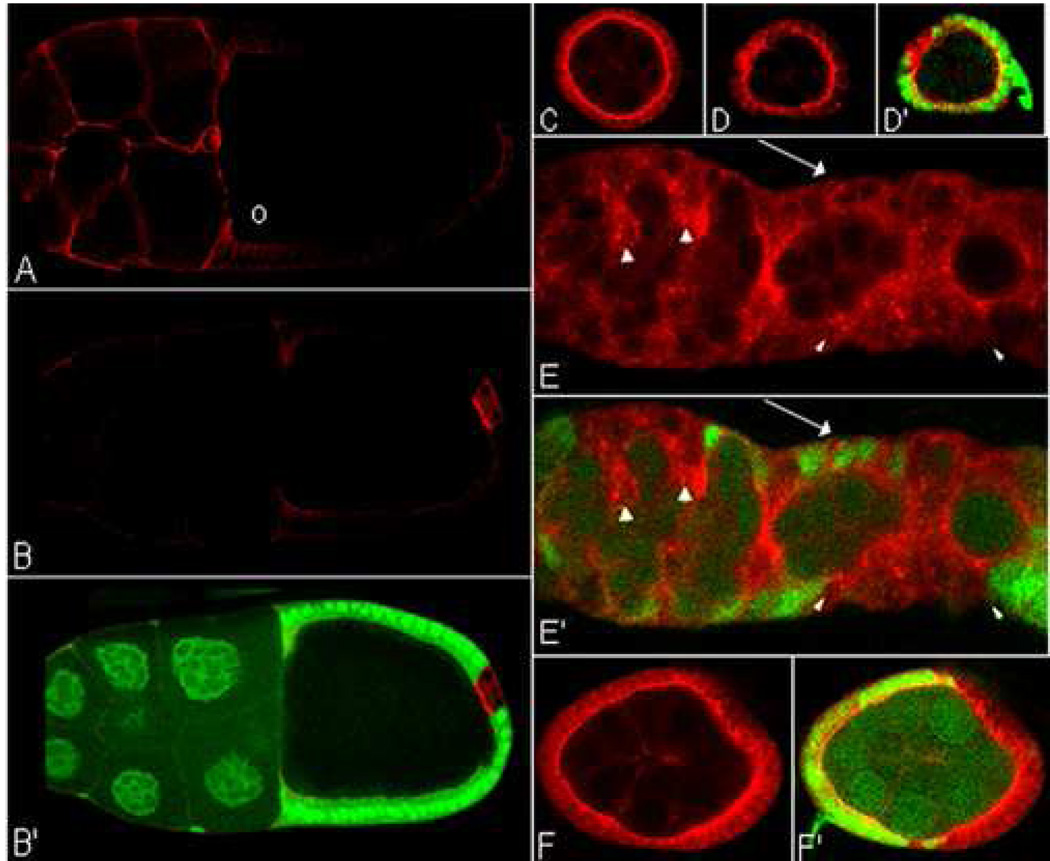

Figure 3. N protein increases in Sxl− clones.

(A–E’) Whole mount ovaries labeled for N (red) and GFP (green) (Sxl− clones marked by the absence of GFP in B’, D’, E’, F’).

(A) wt stage 10 chamber. N is enriched in posterior follicle cells and cells along the anterior of the oocyte (o). (B, B’) Stage 10 chamber showing upregulation of N in a small Sxl− clone. (C) wt pre-vitellogenic egg chamber. (D, D’) N is upregulated in Sxlfollicle cell clone relative to adjacent wt follicle cells. (E, E’) Germarium with Sxlfollicle cell clones and encapsulation defects. Higher levels of N protein are present in clones (arrowheads) compared to wt (arrow). (F, F’) Sxl− follicle cell clones in hsp83-traF show upregulation of N.

The egg chamber packaging defects associated with Sxl− clones are expected to arise in the germarium when newly formed cysts are being encapsulated. It is interesting in this regard that when Sxl− clones are seen in the germarium, encapsulation defects are often also evident. The example shown in Fig 3E is a larger than normal germarium containing excess follicle cells and a single enlarged “nurse cell” posterior to an apparent stage 1 chamber. Finally, as was observed for the other follicle cell phenotypes, we found that the elevated levels of N protein in Sxl− clones are not rescued by hsp83-traF (Fig 3F,F’).

These findings would be consistent with a model in which defects in follicular development occur when Sxl activity is lost because N is inappropriately upregulated in Sxl− cells. In this case it should be possible to generate similar phenotypes by juxtaposing cells with higher than normal levels of N activity next to cells with wild type levels of N. For this purpose we used an Act5C>y+>Nintra transgene (Struhl et al., l993) and either hsp70 Flp or e22c-Flp to induce random follicle cell clones expressing the constitutively active Nintra protein. As shown in Fig 1J, clonal expression of Nintra induces egg chamber packaging defects. Moreover, whereas the majority of Nts1 packaging defects are partitioned egg chambers, random clones of Nintra produced mostly combined chambers as is seen when Sxl is lost. Also like Sxl−, we found extra sets of FasIII expressing cells in many Nintra chambers (Fig 2H). Similar results were obtained when we generated clones expressing another activated N, NΔ34a (Doherty et al., l996) (data not shown).

Sxl is downregulated in cells expressing high levels of Notch protein

Although Sxl is expressed in all female cells from early in development through the adult stage, the level and intracellular localization of the protein varies not only from one cell type to another but even within specific tissues. Differences in the level and localization of Sxl were first observed in germline stem cells and cysts of the germarium (Bopp et al., 1993). Very high levels of predominantly cytoplasmic Sxl are present in the stem cells, while in their progeny, the cystoblasts and cysts, the levels drop dramatically and the remaining protein is largely nuclear. Subsequent studies showed that the turnover and relocalization of Sxl in the germline cystoblasts and cysts is mediated by the hedgehog (hh) signaling pathway (Vied and Horabin, 2001) and that this pathway also targets Sxl in wing discs (Horabin et al., 2003).

Variations in the level and localization of Sxl in the follicular epithelium would be expected to impact its ability to downregulate N protein accumulation. For this reason we examined the expression of N and Sxl in wild type ovaries. As shown in Fig 4A–A’’, high levels of N accumulate in several clusters of follicle cells in the germarium. Typically the most intensely labeled cluster is located in the region between the anterior pole of the encapsulated egg chamber in region 3 and the posterior pole of the 16 cell cyst in region 2b (see arrowhead in Fig 4A; Xu et al., 1992). As would be predicted if Sxl functions as a negative regulator of N expression in the follicular epithelium, the level of Sxl in these clusters (see arrowheads in Fig 4A’, A’’) is lower than in the main body follicle cells in region 3 (see arrows in Fig 4A’) and usually predominantly nuclear. Based on their location, these clusters are expected to be precursors for the stalk cells that separate individual chambers and for the polar cells that mark the anterior and posterior ends of the chamber (King, 1970).

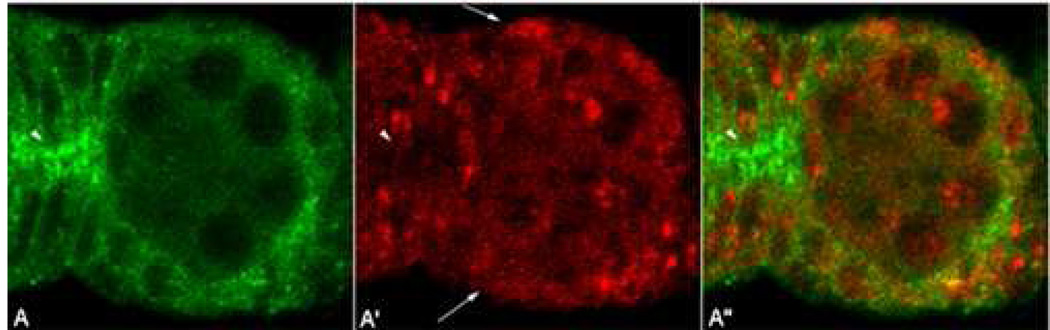

Figure 4. Sxl is downregulated and N is upregulated in wt germaria.

High resolution image of the posterior region of an Oregon R germarium labeled for N (green) and Sxl (red). High levels of N are observed in polar and stalk cell precursors (arrowhead). Sxl is cytoplasmically downregulated in these cells compared to main body follicle cells (arrows). (Punctuate Sxl protein expression pattern indicates nuclear localization.)

Sxl binds N mRNA

Sxl exerts its regulatory effects on splicing and translation by interacting with polyuridine runs of 7 or greater nucleotides in length in the introns and UTRs of target RNAs. The association of Sxl protein with one of its known targets, Sxl pre-mRNAs, has been visualized directly in vivo in salivary gland polytene chromosomes by Samuels et al., (l994). Interestingly, these authors found that Sxl protein also associated with nascent transcripts at the X chromosomal band 3C7 which corresponds to the N locus. This observation suggested to us that Sxl might regulate N protein expression by binding directly to N transcripts. Consistent with this idea, we found that N mRNAs have consensus Sxl binding sites in both the 5’ and 3’ UTRs. The N 5’ UTR has two consensus sequences, while the 3’ UTR has four consensus sequences (Fig 5A).

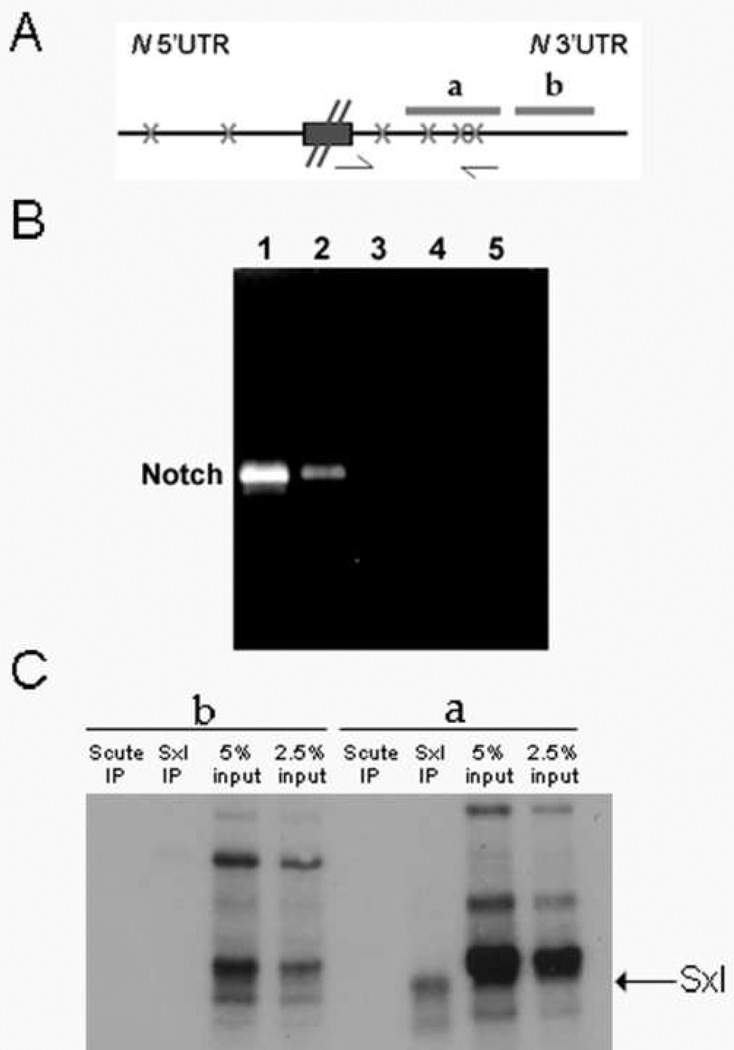

Figure 5. Sxl binds N mRNA.

(A) Schematic of important sequences in N 5’ and 3’ UTRs. Xs mark the location of putative Sxl binding sites, arrows indicate location of primers used for PCR in B, while a and b correspond to 32P-labelled RNA probes containing either 3 or 0 Sxl binding sites.

(B) Sxl IP followed by RT-PCR for N mRNA indicate that Sxl can bind N mRNA. Lane 1: Positive control RT-PCR for N from ovarian extract. Lane 2: Sxl IP followed by RTPCR for N. Lane 3: Negative control Scute IP followed by RT-PCR for N. Lane 4: Sxl IP, no reverse transcriptase negative control. Lane 5: Sxl IP, no primers negative control.

(C) In vitro binding experiments using ovarian extract and 32P-labeled probes a & b. Ovarian extracts were incubated with probes, UV crosslinked and then treated with RNase. The extracts were then split into three. One portion was saved as the input control while the other portions were immunoprecipitated with either Sxl or Scute antibody. A 32P labeled protein of the size expected for Sxl is observed in Sxl IPs from the extract incubated with probe a (3 Sxl binding sites). This protein is not detected in the control Scute IP, nor is it detected in the IPs of extracts incubated with the probe b (no Sxl binding sites). Sxl can also be detected in the probe a input sample. It migrates just ahead of the heavily labeled ~40 kd protein.

To determine if Sxl is associated with N mRNAs in ovaries, we immunoprecipitated ovary extracts with Sxl antibody and then used RT-PCR to assay for N mRNA sequences in the immunoprecipitates. For the reverse transcription we used a primer complementary to sequences near the 3’ end of N mRNA. For the PCR amplification we used a forward primer located 700 bp upstream so the product encompasses all four Sxl binding sites in the N 3’UTR (Fig 5A). As shown in Fig 5B, N mRNA was detected in ovarian extract (lane 1) and in Sxl immunoprecipitates (lane 2) but was absent from control Scute immunoprecipitates (lane 3), as well as the no reverse transcriptase and no PCR primers negative controls (lanes 4 and 5). This result indicates that N mRNA is in a complex with Sxl in ovaries.

We next used UV cross-linking to test whether Sxl can bind directly to N mRNA. For these experiments we generated two similar sized 32P labeled RNA probes from the N 3’ UTR. One probe (a) spans 3 of the 4 consensus Sxl binding sites while the other (b) is from a region of the N 3’ UTR that does not contain any consensus binding sites (Fig 5A). Based on the RNA recognition properties of Sxl (c.f., Samuels et al. l994) we expected that Sxl will bind to probe (a) but will not bind to the probe (b) lacking these sites. The two 3’ UTR probes were incubated with ovarian extracts, UV cross-linked and then immunoprecipitated with either Sxl or the control Scute antibody (see legend to Fig 5). We then visualized the 32P labeled proteins in the immunoprecipitates and in the starting extracts by autoradiography. Fig 5C shows that Sxl in ovarian extracts can be crosslinked to the N 3’ UTR probe that contains the consensus binding sequences but cannot be crosslinked to the N 3’ UTR probe which lacks these sequences.

Sxl downregulates N in the developing wing

Since the known N mRNA species have recognition sequences for Sxl in their 5’ and 3’ UTRs, Sxl should be able to bind to N mRNAs in tissues besides the ovary and salivary glands and hence could potentially regulate N accumulation in other developmental contexts. One such context is the wing. N is haploinsufficient in females for wing development and females heterozygous for strong N mutations have notched wings. It seemed possible that Sxl might contribute to the wing phenotype seen in female N−/+ flies by downregulating N in the developing wing disc. To test this idea we asked if the notch wing phenotype in N−/+ females is sensitive to Sxl.

As illustrated in Fig 6B, most N264-40/+ females have a moderate notch wing phenotype (Fig 6E), defined as a small notch at the tip of the wing. We found that deleting one copy of the Sxl gene suppresses this phenotype and most Sxl7BO/N264-40 trans-heterozygous females have little if any notching. Instead only a few hairs are missing from the tip of the wing margin (Fig 6C, E). These effects do not seem to be due to genetic background as Sxl7BO suppressed the wing phenotype of a second N allele, N55e11. Similarly, the wing phenotype was suppressed by another Sxl mutant, Sxlf1, though to a lesser extent than Sxl7B0 (not shown).

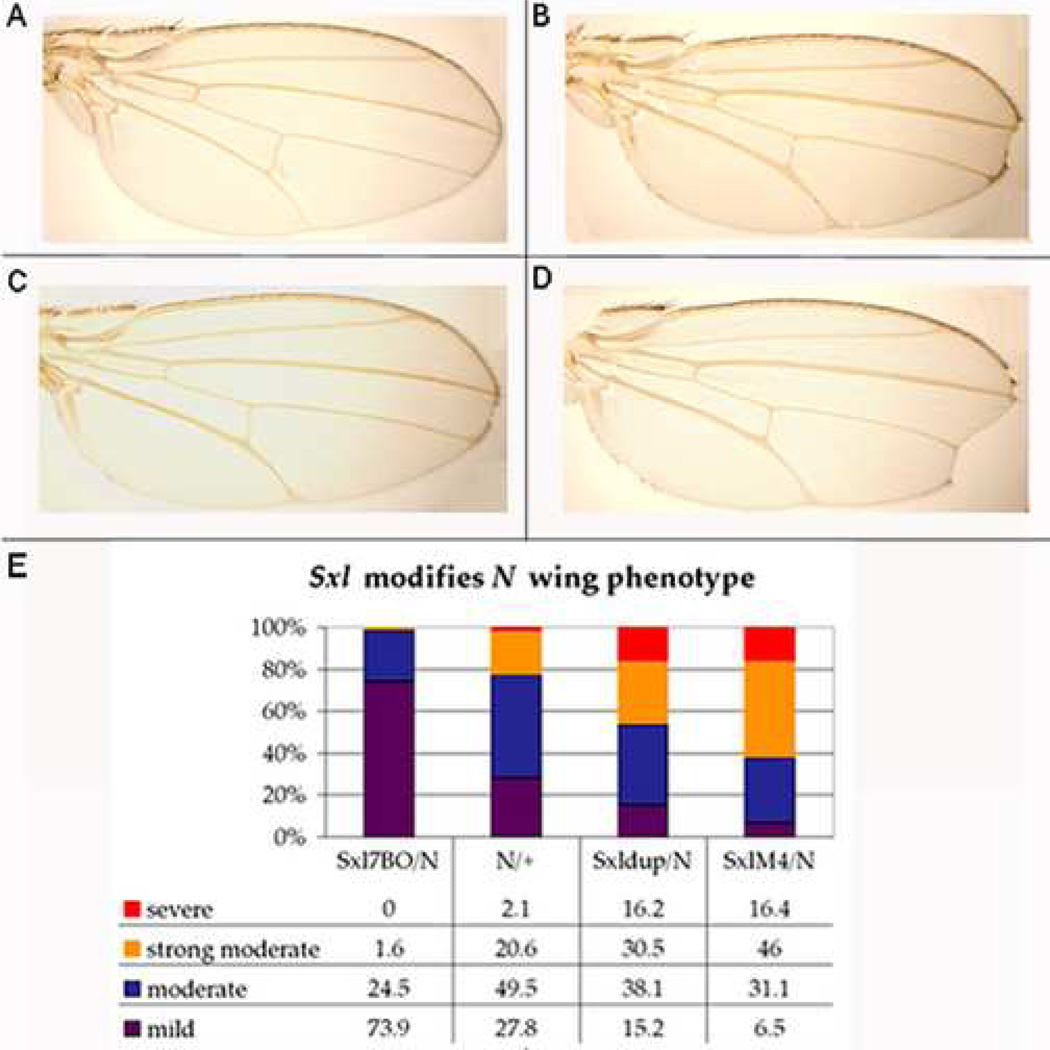

Figure 6. Sxl interacts with N in the developing wing.

Wings from (A) wt, (B) N264-40/+, (C) N264-40/Sxl7BO, and (D) N264-40/SxlM4 adult females. (E) Sxl7BO suppresses N264-40 wing phenotype while Sxldup and SxlM4 enhance.

If reducing Sxl suppresses the N wing phenotype, then increasing its activity might be expected to exacerbate the wing phenotype. Fig 6E shows that as predicted the notched wing phenotype becomes more severe when there are three Sxl genes (+/Sxldup). Even stronger effects were observed when N mutants were trans to the Sxl gain of function allele SxlM4 which expresses more Sxl protein than wild type (Deshpande & Calhoun, personal communication). Most SxlM4/N264-40 females had very strong wing phenotypes, typically observed as a large notch at the wing tip (Fig 6D, E).

Sxl mutations rescue the lethal effects of N hypomorphic alleles

The observation that the notched wing phenotype of N−/+ females is sensitive to Sxl suggested that we might also be able to rescue the lethal effects of hypomorphic N alleles by reducing the Sxl gene dose. To test this possibility we introduced Sxl7B0 into females trans-heterozygous for Nnd3 and N55e11. Normally this combination of N mutations is almost completely lethal and few if any Nnd3/N55e11 females survive. However, we found that we could partially rescue this lethality by deleting one of the two Sxl genes; 17% (41/280) of the Nnd3/N55e11Sxl7BO were viable compared to only 0.3% viability (1/319) of Nnd3/N55e11 females.

Negative regulation of N signaling by Sxl contributes to sexual dimorphism

The effects of altering Sxl activity on the phenotypes produced by N mutations indicate that Sxl must generally downregulate N in females. An important question is whether a general reduction in the activity of this signaling pathway can have sex-specific morphological consequences. To address this question we examined bristle formation in the adult cuticle as it is known to be subject to N regulation.

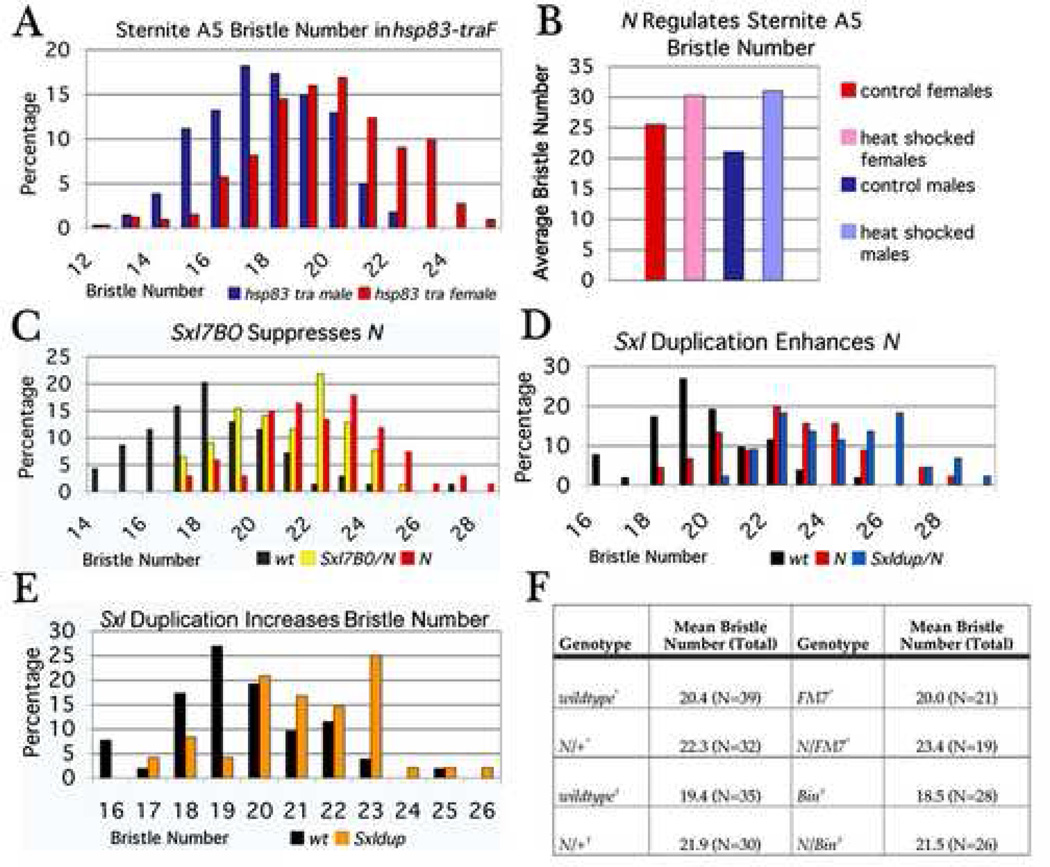

A recent report indicates that females have more bristles than males on sternite A5 (Kopp et al., 2003). Since most sexually dimorphic traits are under the control of dsx we first determined whether bristle number is dependent upon the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru regulatory cascade by feminizing males with the hsp83-traF transgene. Although hsp83-traF males have female abdominal pigmentation and lack sex combs, we found that they are male-like with respect to the number of A5 sternite bristles (Fig 7A). The reciprocal comparison was also true; masculinizing females via a tra mutation did not affect sternite A5 bristles (see legend Fig 7A). These results indicate that the male-female difference in A5 bristle number is independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru cascade.

Figure 7. Regulation of N by Sxl contributes to sexual dimorphism.

(A) hsp83-traF progeny obtained by crossing hsp83-traF /w X w/BsY (N = 673). hsp83-traF males had fewer bristles (mean 17.6, SD 2.0) than hsp83-traF females (mean 19.6, SD 2.39; P<0.00001). Not shown: tra−/tra− females had more bristles (mean 19.5, SD 1.7) than tra−/tra− males (mean 18.2, SD 2.0; P<0.005)

(B) Nts1/Nts1 and Nts1/Y shifted to 29° C for 6 hr, 21 hr APF. Nts1/Nts1 had an average of 30.2 sternite A5 bristles compared to 25.5 bristles observed for non-heat shocked controls. Nts1/ Y had an average of 31.0 sternite A5 bristles compared to 21.0 bristles observed for non-heat shocked controls.

(C) Progeny obtained by crossing Sxl7BO/Bin X N264-40/Y; Dp(1;2)72c21/+ (N = 299). N264-40/Sxl7BO females have fewer bristles (mean 20.8, SD 2.06) than N264-40/+ siblings (mean 22.0, SD 2.38; P<0.005). Not shown: N264-40/Sxlf1 females also had fewer bristles (mean 22.0, SD 2.07) than their N264-40/+ siblings (mean 23.6, SD 1.69; P<0.002).

(D, E) Progeny obtained by crossing Sxldup/FM7 X N264-40/Y; Dp(1;2)72c21/+ (N = 189).

(D) N264-40/Sxldup females had more bristles (mean 24.2, SD 2.25) than N264-40/+ siblings (mean 22.4, SD 2.33; P<0.0002). Not shown: N264-40/+; Sx.FLΔ/+ females had more bristles (mean 23.2, SD 2.31) than their N264-40/+ siblings (mean 21.3, SD 2.52; P<0.0025)

(E) Sxldup/+ females had more bristles (mean 21.2, SD 2.01) than wt siblings (mean 19.6 SD 1.9; P<0.0005). Not shown: Sx.FLΔ/+ females had more bristles (mean 21.4, SD 1.5) than their wt siblings (mean 19.4, SD 1.96; P<0.002).

(F) Effect of FM7 and Bin on bristle number. Although N264-40 increased the number of bristles of wild type, FM7, and Bin females there was no significant difference in bristle number between balancers and nonbalancers. * denotes progeny derived by crossing FM7/+ X N264-40/Y; Dp(1;2)72c21/+. † denotes progeny derived by crossing Bin/+ X N264-40/Y; Dp(1;2)72c21/+.

The role of N in regulating bristle number has been extensively documented for the notum, but it was unclear whether N also influences bristle number on the A5 sternite (Hartenstein and Posakony, 1990). For this reason we investigated the effects of N on the formation of A5 sternite bristles. Homozygous Nts1 flies grown at the permissive temperature were shifted to 29° C for 6 hrs approximately 21 hrs after puparium formation. We then compared the number of A5 bristles in Nts1 flies that had been shifted to 29° C with Nts1 siblings that were allowed to develop entirely at the permissive temperature. We found that the temperature shifted Nts1 females had 20% more bristles on sternite A5 than control siblings. Hemizygous Nts1 males shifted to 29° C had almost 50% more bristles than their control Nts1 sibs (Fig 7B). These results indicate that as is in the notum, N controls bristle number on sternite A5.

Since a reduction in N activity leads to the formation of extra bristles, we reasoned that the difference in A5 bristle number between males and females could be due to the downregulation of N by Sxl. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of manipulating Sxl activity on bristle number. Consistent with the extra bristle phenotype of Nts1, females heterozygous for N264-40 have more bristles on the A5 sternite than wild type females (Fig 7C, D). If Sxl’s downregulation of N affects bristle number, then reducing Sxl activity would be predicted to decrease the number of sternite A5 bristles in these N264-40/+ females. As shown in Fig 7C, this is the case. To control for allele specificity and genetic background effects, we tested Sxl7BO and Sxlf1 and found that both alleles decreased sternite A5 bristle number to a similar extent (see legend Fig 7C).

Our hypothesis also predicts that increasing Sxl activity should increase the number of sternite A5 bristles. Fig 7D shows that 3 copies of Sxl (+/Sxldup) increases the number of A5 bristles in N264-40/+ females. Moreover, an extra Sxl gene even seems to increase the number of A5 bristles in a background that is wild type for N compared to females carrying only 2 Sxl genes (Fig 7E).

Although we saw that an extra Sxl gene and SxlM4 were both strong enhancers of N in the wing, we did not see a statistically significant increase in bristle number with SxlM4. In order to make sure that the effects of Sxldup on bristle formation are due to increased Sxl activity rather than to one of the other genes in the duplication or genetic background, we tested a transgene that expresses full length Sxl protein from the hsp83 promoter (Sx.FLΔ, Yanowitz et al., 1999). When this transgene is introduced into N264-40/+ females, the number of A5 sternite bristles is increased. Moreover, like Sxldup, wild type females carrying Sx.FLΔ had a greater number of A5 sternite bristles than wild type females that lacked the transgene (see legend Fig 7D, E).

Discussion

Sxl is a negative regulator of the N signaling pathway

While it has long been known that Sxl must control some aspects of sexual dimorphism by mechanisms that are independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx -fru regulatory cascade, our understanding of what these morphological features might be and of how this might be accomplished has remained rudimentary. In the studies reported here we have uncovered a regulatory link between Sxl and the N signaling pathway. We show that Sxl impacts the functioning of this pathway in a sex-specific fashion by negatively regulating N itself.

Several lines of evidence support the conclusion that the N signaling pathway is a target for Sxl regulation. First, N and Sxl show genetic interactions in a variety of different developmental contexts. In the ovary, egg chamber packaging defects are induced when homozygous Nts1 females are placed at the non-permissive temperature. Eliminating one copy of the Sxl gene dominantly suppresses these egg chamber packaging defects. In female wing discs, N is haploinsufficient for the formation of the tip of the wing blade. This haploinsufficiency is sensitive to the Sxl gene dose. The N wing phenotype is suppressed when females have only one functional Sxl gene while it is exacerbated when females have three functional Sxl genes. Like wing development, N is “haploinsufficient” in females for bristle formation in the A5 sternite and bristle number is increased in heterozygous flies. This bristle phenotype is suppressed when the N−/+ females have only one Sxl gene while it is enhanced when the females have three Sxl genes. Finally, the female lethal effects of a combination of loss of function N alleles can be suppressed by reducing the Sxl dose. Taken together, these genetic interactions argue that Sxl must negatively regulate the N pathway. Moreover, in each of these contexts the regulatory interactions between Sxl and N must be independent of both the Sxl→tra→dsx –fru regulatory cascade and of the msl dosage compensation system. The reason for this is that Sxl is not haploinsufficient for either tra splicing or for turning off the msl-2 dosage compensation system and in females heterozygous for Sxl, both of these regulatory pathways are fully in the female mode. Likewise, adding an extra dose of Sxl would not hyperfeminize tra nor would it further repress msl-2 translation. In this context, it should also be pointed out that Sxl negatively regulates its own expression through binding sites in the UTRs of Sxl mRNAs (Yanowitz et al., l999). Because of this negative autoregulatory feedback loop, the levels of Sxl protein in both Sxl−/+ and Sxldup/+ females are maintained close to that in wild type females. Thus, we are likely underestimating the effects of Sxl on N activity in our genetic interaction experiments.

The second line of evidence is the substantial upregulation of N protein in Sxl−follicle clones. We have shown that this upregulation is independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx –fru regulatory cascade; however, in this case, we suspect that two factors likely contribute to the observed increase in N protein. The first is the loss of Sxl regulation, while the second is the activation of the msl-2 dosage compensation system in the complete absence of Sxl activity. As the latter is expected to generate only a 2-fold increase in N expression it would not fully account for the effects of losing Sxl activity in the clones (c.f., the N levels in adjacent stage 10 Sxl+ and Sxl− follicle cells).

Finally, like the two known targets for translational regulation by Sxl, msl-2 and Sxl, N mRNA has multiple Sxl binding sites in its UTRs. Moreover, as would be expected if Sxl directly downregulated N protein accumulation by controlling the translation of N message, Sxl binds to N mRNAs in ovaries. It is interesting to note that the configuration of Sxl binding sites in N mRNAs is quite similar to msl-2. Both mRNAs have two Sxl binding sites in the 5’UTR and four in the 3’UTR. In spite of the similarity in the number and distribution of Sxl binding sites, Sxl repression of N mRNA translation must differ from its repression of msl-2 mRNA translation because unlike Msl-2, N protein is expressed in females. One factor that might account for this difference is that repression of msl-2 mRNA translation by Sxl depends upon corepressors that interact with sites in the 3’ UTR located adjacent to the Sxl binding sites (Grskovic et al., 2003); however, these putative co-repressor recognition sequences are not present next to the Sxl binding sites in the N 3’UTR.

Regulation of N signaling by Sxl contributes to sexual dimorphism

The N signaling pathway plays a central role in fly development because of its ability to specify alternative cell fates. Since most of the tissues and cell types in which the N pathway functions are present in both males and females, an obvious question is how Sxl can deploy this pathway to generate sex-specific differences in morphology. Our results indicate that in common tissues Sxl is able to generate sex-specific differences by changing the level of N activity. Thus, in the A5 sternite the number of bristles in females is greater than in males and this difference is due to the downregulation of N by Sxl in female flies. As in other parts of the adult cuticle, bristle formation in A5 depends upon the level of N activity. The number of bristles is inversely proportional to N activity and N heterozygous females have a greater number of bristles than wild type females. This difference can be suppressed by reducing Sxl activity and magnified by increasing Sxl activity. Excess Sxl activity can also cause an increase in the number of A5 bristles in females that are wild type for N. It is reasonable to suppose that this general downregulation of N by Sxl will contribute to other morphological differences between males and females that are independent of the Sxl→tra→dsx –fru regulatory cascade such as bristle number in other parts of the adult cuticle, size of tissues and organs and perhaps some as yet unknown aspects of nervous system development.

Since the ovary is only present in females the developmental context for Sxl-N regulatory interactions is different from most other tissues in the fly. Like the wing and sternites, Sxl negatively regulates N in the ovarian follicular epithelium. When Sxl activity is lost in follicle cells, we observe a variety of defects in the development of this epithelium including egg chamber packaging defects, ectopic polar cells and extra long interfollicular stalks. This spectrum of phenotypes closely resembles those seen when there is excess N activity, and argues that N must be inappropriately upregulated in the follicular epithelium when Sxl is lost. Consistent with this suggestion, elevated levels of N protein are found in Sxl clones. With the possible caveat that the MSL dosage compensation system is likely activated in the absence of Sxl and thus probably contributes to the upregulation of N protein, these observations suggest that Sxl plays an important role in mediating N specification of cell fate as the follicular epithelium develops. This view is supported by the reciprocal patterns of N and Sxl protein accumulation in the germarium of wild type females. We find that follicle cells expressing high levels of N in the germarium have only little cytoplasmic Sxl, while lower levels of N are found in follicle cells that have high amounts of cytoplasmic Sxl. If, as we suspect, Sxl regulates N at the level of translation, the turnover of cytoplasmic Sxl and/or its relocalization to the nucleus would be expected to lead to the upregulation of N protein expression. Conversely, in cells that retain abundant cytoplasmic Sxl, N expression should remain repressed. Since the cells in the germarium that are induced to express high levels of N are thought to be the progenitors of the stalk and polar cells, releasing N mRNA from translation inhibition by Sxl would be expected to facilitate the specification of these cell types by the N signaling pathway.

This raises the question of why cytoplasmic Sxl turns over and/or is targeted to the nucleus in these particular cells. In the germline and in the wing disc turnover and nuclear targeting of Sxl protein is known to be mediated by the hh signaling pathway (Horabin et al., 2003; Vied and Horabin, 2001). It seems possible that hh signaling might also promote the turnover/nuclear targeting of Sxl in these particular somatic follicle cells. Consistent with this idea, overexpression of hh in follicle cells leads to at least one of the phenotypes that is seen when Sxl activity is lost (or N is ectopically activated), the expansion of interfollicular stalks (Forbes et al., 1996). If hh is responsible for the turnover/nuclear targeting of Sxl, the Sxl gene would provide a mechanism for linking the hh and N signaling pathways in the specification of stalk and polar cell fates. Further studies will be required to test this model.

Experimental Procedures

Fly Stocks

Sxl and N alleles: Sxl7BO, SxlM4, Sxldup (Dp(1;1)jnR1-A) , Sxlf1, N55e11, N264-40, Nts1, Nnd3. The following recombinants were generated: N55e11Sxl7BO/Bin, yNts1Sxl7BO/Bin, ywSxl7BO FRT 19A/FM7, P{w+, otu::Sxl}, fl(2)d1/Cyo.

Statistical Calculations

One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to analyze the statistical significance of the difference in means of sternite A5 bristle number.

Immunohistochemistry

Ovaries from 2–6 day old females were dissected, fixed, and stained as in Bopp et al.1993, except GFP samples were fixed for 10 min. Samples were blocked and permeablilized for 1 hr PBSTT+10 mg/ml BSA and antibodies were diluted into PBSTT+1 mg/ml BSA. Antibodies (from DSHB, Iowa) were: Sxl m18 (1:10), Orb 4H8 (1:30), FasIII 7G10 (1:100), Eya 10H6 (1:10), N C17.9C6 (1:10). N rabbit polyclonal was generous gift from S. Artavanis-Tsakonas (1:300). Alexa fluorophore conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:500 (Molecular Probes). Hoechst was used to visualize DNA (1:1000, 7 min. at RT).

Immunoprecipitations

Ovaries from 20 females were dissected and extracts prepared as in Tan et al. 2001. After two freeze/thaw cycles, the extract was centrifuged 2X at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The extract was incubated with 400µl modified IP buffer (50 mM NaCl, 0.05% triton, omit NP-40), RNAsin and 10 µl Protein A beads crosslinked to either Sxl m104 and m114 or Scute 5A10 (Deshpande et al., 1995) for 1 hr at RT. Beads were washed 3X with 1 ml modified IP buffer. RNA was then extracted from the beads using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center) and precipitated with isopropanol. RNA pellet was rinsed with 80% ethanol and dried by centrifugation under a vacuum for 2 min. Pellet was resuspended in DEPC-treated water and treated with RNAse-free DNAse. RT-PCR was performed with the following primers: TGTGTCAACTTAAATCAAACAG for RT, GCTAAGTTCGATCTAAAATATGC and GAATCTTTTTACAGTTTAGCTTAGTC for PCR. 20% of the cDNAs were PCR amplified with 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min., 45 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

UV crosslinking

The probe corresponding to the N 3’ UTR region containing 3 Sxl binding sites was amplified using forward primer: GGCCATAAGACTACGCTAAG and reverse primer: TTAGTCAATATGTAATAATACATAATAGTC. For the probe containing no Sxl binding sites, forward primer: GTTGACACATACAAAATACAAAAG and reverse primer: CTTTTCATCAACTTAGATCGTAG. PCR products were cloned using the pCRIITOPO vector (Invitrogen) and then used as templates to in vitro transcribe 32P-labeled probes. Ovarian extract was made as described above. UV crosslinking experiments were as in Samuels et al l998. After RNase treatment, samples were incubated with Protein A beads crosslinked to antibodies as described above (omitting RNAsin). Samples were incubated for 1 hr at RT followed by 3–4 washes with modified IP buffer. This was followed by boiling samples in loading buffer, SDS-PAGE, transfer to nitrocellulose, and autoradiography.

Acknowledgements

We thank Girish Deshpande for many helpful conversations and critical reading of the manuscript as well as Trudi Schupach for very beneficial discussions. We thank Spyros Artavanis-Tsakonas for N polyclonal antibody and Tom Cline, Denise Montell, Helen Salz, Lucas Sanchez, Trudi Schupbach, Gary Struhl, Juan Valcarcel, Cedric Wesley, and the Bloomington Stock Center for flies. We thank Joe Goodhouse for help with the confocal microscope and Gordon Gray for providing fly food. This work was supported by an NIH grant to P.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad SM, Baker BS. Sex-specific deployment of FGF signaling in Drosophila recruits mesodermal cells into the male genital imaginal disc. Cell. 2002;109:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Montell D. Eyes absent, a key repressor of polar cell fate during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5377–5388. doi: 10.1242/dev.00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender LB, Kooh PJ, Muskavitch MA. Complex function and expression of Delta during Drosophila oogenesis. Genetics. 1993;133:967–978. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.4.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp D, Horabin JI, Lersch RA, Cline TW, Schedl P. Expression of the Sex-lethal gene is controlled at multiple levels during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1993;118:797–812. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtis KC, Coschigano KT, Baker BS, Wensink PC. The doublesex proteins of Drosophila melanogaster bind directly to a sex-specific yolk protein gene enhancer. EMBO J. 1991;10:2577–2582. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline T, Meyer B. Viva la difference: males vs females in flies vs worms. Annu Rev Genet. l996;30:637–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande G, Stukey J, Schedl P. scute (sis-b) function in Drosophila sex determination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4430–4440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty D, Feger G, Younger-Shepherd S, Jan LY, Jan YN. Delta is a ventral to dorsal signal complementary to Serrate, another Notch ligand, in Drosophila wing formation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:421–434. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes AJ, Lin H, Ingham PW, Spradling AC. hedgehog is required for the proliferation and specification of ovarian somatic cells prior to egg chamber formation in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1125–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammont M, Irvine KD. fringe and Notch specify polar cell fate during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2001;128:2243–2253. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granadino B, San Juan A, Santamaria P, Sanchez L. Evidence of a dual function in fl(2)d, a gene needed for Sex-lethal expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1992;130:597–612. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grskovic M, Hentze MW, Gebauer F. A co-repressor assembly nucleated by Sex-lethal in the 3'UTR mediates translational control of Drosophila msl-2 mRNA. EMBO J. 2003;22:5571–5581. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Schupbach T. Cct1, a phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis enzyme, is required for Drosophila oogenesis and ovarian morphogenesis. Development. 2003;130:6075–6087. doi: 10.1242/dev.00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager JH, Cline TW. Induction of female Sex-lethal RNA splicing in male germ cells: implications for Drosophila germline sex determination. Development. 1997;124:5033–5048. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V, Posakony JW. A dual function of the Notch gene in Drosophila sensillum development. Dev Biol. 1990;142:13–30. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90147-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins NC, Thorpe J, Schupbach T. Encore, a gene required for the regulation of germ line mitosis and oocyte differentiation during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1996;122:281–290. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horabin JL, Walthall S, Vied C, Moses M. A positive role for Patched in Hedgehog signaling revealed by the intracellular trafficking of Sex-lethal, the Drosophila sex determination master switch. Development. 2003;130:6101–6109. doi: 10.1242/dev.00865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SM, Blochlinger K. cut interacts with Notch and protein kinase A to regulate egg chamber formation and to maintain germline cyst integrity during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3663–3672. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keisman EL, Baker BS. The Drosophila sex determination hierarchy modulates wingless and decapentaplegic signaling to deploy dachshund sex-specifically in the genital imaginal disc. Development. 2001;128:1643–1656. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.9.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RC. Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster. New York: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A, Duncan I, Godt D, Carroll SB. Genetic control and evolution of sexually dimorphic characters in Drosophila. Nature. 2000;408:553–559. doi: 10.1038/35046017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A, Graze RM, Xu S, Carroll SB, Nuzhdin SV. Quantitative trait loci responsible for variation in sexually dimorphic traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;163:771–787. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz V, Chang JS, Horabin JL, Bopp D, Schedl P. The Drosophila orb RNA binding protein is required for the formation of the egg chamber and establishment of polarity. Genes Dev. 1992;8:598–613. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MK, Holder K, Yost C, Giniger E, Ruohola-Baker H. Expression of constitutively active Notch arrests follicle cells at a precursor stage during Drosophila oogenesis and disrupts the anterior-posterior axis of the oocyte. Development. 1996;122:3639–3650. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagengast AA, Stitzinger SM, Tseng CH, Mount SM, Salz HK. Sex-lethal splicing autoregulation in vivo: interactions between SEX-LETHAL, the U1 snRNP and U2AF underlie male exon skipping. Development. 2003;130:463–471. doi: 10.1242/dev.00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruohola H, Bremer KA, Baker D, Swedlow JR, Jan LY, Jan YN. Role of neurogenic genes in establishment of follicle cell fate and oocyte polarity during oogenesis in Drosophila. Cell. 1991;66:433–449. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels ME, Bopp D, Colvin RA, Roscigno RF, Garcia-Blanco MA, Schedl P. RNA binding by Sxl proteins in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4975–4990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels M, Deshpande G, Schedl P. Activities of the Sex-lethal protein in RNA binding and protein:protein interactions. NAR. 1998;26:2625–2637. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L, Gorfinkiel N, Guerrero I. Sex determination genes control the development of the Drosophila genital disc, modulating the response to Hedgehog, Wingless and Decapentaplegic signals. Development. 2001;128:1033–1043. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC. Developmental genetics of oogenesis. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. In the development of Drosophila melanogaster. Plainview, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzinger SM, Conrad TR, Zachlin AM, Salz HK. Functional analysis of SNF, the Drosophila U1A/U2B" homolog: identification of dispensable and indispensable motifs for both snRNP assembly and function in vivo. RNA. 1999;5:1440–1450. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Fitzgerald K, Greenwald I. Intrinsic activity of the Lin-12 and Notch intracellular domains in vivo. Cell. 1993;74:331–345. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90424-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Chang JS, Costa A, Schedl P. An autoregulatory feedback loop directs the localized expression of the Drosophila CPEB protein Orb in the developing oocyte. Development. 2001;128:1159–1169. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vied C, Horabin JI. The sex determination master switch, Sex-lethal, responds to Hedgehog signaling in the Drosophila germline. Development. 2001;128:2649–2660. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterbury JA, Horabin JI, Bopp D, Schedl P. Sex determination in the Drosophila germline is dictated by the sexual identity of the surrounding soma. Genetics. 2000;155:1741–1756. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Caron LA, Fehon RG, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The involvement of the Notch locus in Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1992;115:913–922. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanowitz JL, Deshpande G, Calhoun G, Schedl P. An N-terminal truncation uncouples the sex-transforming and dosage compensation functions of sex-lethal. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3018–3028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]