Abstract

Objective

We examined verbal list memory in participants with pathology-confirmed or biomarker supported diagnoses to clarify inconsistencies in comparative memory performance. We hypothesized that AD participants would show more rapid forgetting whereas bvFTD participants would show a more dysexecutive pattern. We also explored differences in medial temporal volumes, and relative frontal and medial temporal area contributions to memory consolidation.

Participants and Methods

Participants had clinical diagnoses of AD and bvFTD that were pathologically confirmed at autopsy or supported with PiB amyloid imaging. We used cognitive and imaging data collected at baseline visits for a sample of 26 participants with AD (mean age=63.7, education=16.2, CDR=0.8), 25 participants with bvFTD (mean age=60.7; education=15.7; CRD=1.1), and 25 healthy controls (mean age=65.6; education=17.5; CDR=0.2).

Results and Conclusions

AD participants showed more rapid forgetting than bvFTD and both groups showed more rapid forgetting than controls. In contrast, bvFTD did not conform to a more dysexecutive pattern of performance as patient groups committed similar number of intrusion errors and showed comparably low rates of improvement on cued recall and recognition trials. For patients with neuroimaging, there were no group differences in medial temporal volumes, which was the only significant predictor of consolidation for both dementia groups.

Search terms: Alzheimer's disease, Frontotemporal dementia, Cognitive neuropsychology in dementia, Memory, Pathology

Behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a behavioral syndrome marked by significant personality changes and deficits in executive functions. It is often assumed that memory remain relatively intact until the later stages, 1, 2, 3 and impaired memory performances are secondary to poor organization and retrieval rather than memory consolidation. In contrast, impaired consolidation is typical of AD, presumably related to medial temporal lobe dysfunction. However, empirical studies of memory differences between bvFTD and AD have yielded inconsistent results.

Hutchinson and Mathias4 recently published a meta-analytic review of data from 94 studies with 2936 individuals with AD and 1748 individual with FTD. Their results indicated that, in general, participants with FTD performed significantly better on memory tests than AD participants and had better delayed recall on various memory measures. However, their review combined results of clinical and pathological studies and did not differentiate between the behavioral and language subtypes of FTD. Another study, examining memory specifically in bvFTD patients also found that this group outperformed AD participants on delayed recall of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.5 Comparing word recall in clinicopathological groups of AD, bvFTD and normal controls, Bertoux et al.6 found that the dementia groups performed worse than the control group, and that bvFTD patients outperformed AD patients on all memory scores.

By contrast, Hornberger7 concluded that memory for a word-list was similarly impaired in pathology-confirmed group of bvFTD and AD participants, with the exception of recognition, which showed a bvFTD advantage. Similar results were seen in a non-pathology confirmed clinical sample, where levels of immediate and delayed word-list recall were not significantly different between AD and bvFTD8. However, this study also found no significant group difference in recognition performance.

The current study adds to the growing literature examining memory in clinicopathological groups of AD and bvFTD participants6 by using participants whose clinical diagnoses were confirmed using pathology at autopsy or supportive amyloid imaging. Our study is unique in that we specifically focus on memory consolidation, which is particularly dependent on medial temporal structures. We hypothesized that AD participants would show impaired consolidation relative to bvFTD. In contrast, we hypothesized a more dysexecutive pattern of memory dysfunction in bvFTD, marked by disproportionate difficulty with free recall relative to cued recall and recognition.10,11 Some research has also suggested that frontal-lobe based impairments in memory are associated with more memory errors,10,12 so we tested the hypothesis that bvFTD participants would have more intrusion errors than AD participants. Finally, we explored whether diagnostic differences in memory performance could be attributed to differences in medial temporal lobe volumes.

Methods

Sample

Participants were identified from a dataset of 256 individuals seen at the University of California, San Francisco Memory and Aging Center (UCSF MAC) who underwent pathological or biomarker studies in addition to receiving clinical diagnoses. We also identified 25 healthy controls who had normal neurological evaluations (CDR=0, MMSE > 25) and reported absence of cognitive decline over the past 12-months.

Pathological diagnoses were made at autopsy by consensus diagnosis by a team of neuropathologists using methods described elsewhere.13, 14 AD pathology was diagnosed according to Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease scores (CERAD),15 NIA and Reagan Institute Working Group,16 the Consensus Conference on Dementia with Lewy bodies17 and Braak and Braak staging criteria.18 Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology was diagnosed using published criteria.19 Biomarker findings were established with PET imaging through the use of amyloid-β ligand Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), following previous methods,20 for participants for whom autopsy data was not available. Clinical diagnoses were consensus diagnoses by an interdisciplinary team of neurologists, neuropsychologists, nurses and social workers. Diagnoses of AD were given using the criteria for probable AD as delineated by NINCDS-ADRDA21 and bvFTD was diagnosed using the criteria for possible or probable FTD as delineated by the international consensus criteria for bvFTD (FTDC).22

Cases were selected if pathological or amyloid imaging was conclusive and classifiable as either AD or FTLD and if they matched the clinical diagnoses of AD and bvFTD (other FTD or mixed diagnoses were excluded). Exclusion criteria included inconsistencies between clinical and pathological or biomarker diagnoses, age greater than 80 years, MMSE<18, presence of aphasia, or the clinical or pathological diagnosis of a neurodegenerative illness other than AD or bvFTD.

Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above, we narrowed our participant pool to 25 AD and 25 bvFTD participants who met our clinical and pathological criteria. Of the 25 AD participants selected for these analyses, we confirmed AD diagnosis via pathology report in 12 participants and PiB-positive status in 13 participants. Of the 25 bvFTD participants selected, we confirmed diagnosis via pathology report in 18 participants (1 aFTLD-Ubiquitin, 1 FTLD-Cortical Basal Degeneration, 2 FTLD- Motor Neuron Disease, 8 FTLD-TAR DNA-binding Protein, 5 FTLD-Tauopathy, 1 FTLD-Fused in Sarcoma) and PiB-negative status in 7 participants. For these identified participants, data was pulled from the first neuropsychological assessment at the UCSF MAC.

Dementia Severity Measure

The Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE)23 was administered as a measure of general cognitive functioning and was used to exclude severely demented participants with global cognitive declines, however, the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDRS)24 was used to measure dementia severity. This instrument rates functional performance in the areas of memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. A five-point symptom severity scale (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3) is used to grade functioning in each domain, with zero representing no symptoms or functional impairment and a score of three indicating severe symptoms and/or impairment. Total scores range from zero to three and represent a weighted average of the domain scores with memory considered as the primary category. To obtain this data, a registered nurse or social worker privately interviewed each participant’s family member(s) or close friend(s).

Memory Measure

The short form version of the California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-SF)25 was administered to all participants as part of a comprehensive neuropsychological battery. This measure assesses recent episodic memory using a 9-word list presented over four learning trials. An immediate free recall follows a 30-second distracter task. Free recall and semantically cued recall trials are administered after a 10 minute delay. A recognition trial is also given which offers the nine target words as well as nine semantically related and nine semantically novel distracter words. Primary dependent variables were recall on each of the four learning trials, 10-minute delayed free and cued recall, and 10-minute delayed recognition (d- prime). When testing our hypothesis about recall versus recognition, delayed recall and d- prime were transformed using the Blom scaling transformation procedure in order to place them into the same metric for direct comparison using GLM.

Structural Neuroimaging

MRI scans were obtained on 3 different scanners. Five participants (2 AD, 3 bvFTD) were scanned using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens (Siemens, Iselin, NJ) TIM Trio scanner equipped with a 12-channel head coil located at the UCSF Neuroscience Imaging Center. Three participants (1 AD, 2 bvFTD) had imaging from a 4.0 Tesla Bruker MedSpec whole body scanner equipped with an 8-channel head coil located at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (SFVA) Medical Center. The remaining 19 participants with neuroimaging were scanned using a 1.5 Tesla Siemens (Siemens, Iselin, NJ) scanner equipped with a standard head coil at the SFVA Medical Center (11 AD, 8 bvFTD). Whole brain images were acquired using volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (MPRAGE; TR/TE/TI = 2300/2.90/900 ms, α = 9° for the 3T scanner; TR/TE/TI = 2300/3/950 ms, α = 7° for the 4T scanner; TR/TE/TI = 9/4/300 ms, α = 15° for the 1.5T scanner). The field of view for all scanners was 256×256 mm and all had a 1.0×1.0×1.0 mm voxel size, with the exception of the 1.0×1.5×1.0 mm voxel size for the 1.5T scanner. Caution should be exercised when interpreting the imaging data as it was collected from 3 different scanners with different parameters.

FreeSurfer

The T1 MPRAGE structural MR images were analyzed using the FreeSurfer 5.1 image analysis suite, documented at http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu. The software has been validated and described in detail by previous publications.26–28 FreeSurfer is a surface-based structural MRI analysis tool that segments white matter and tessellates gray and white matter surface. 29 The procedure involves the removal of non-brain tissue using a hybrid watershed/surface deformation procedure28 and intensity normalization, 30 followed by automated Talairach transformation and volumetric segmentation of cortical and subcortical gray and white matter, subcortical limbic structures, ventricles, and basal ganglia.31, 32 Estimated total intracranial volume (ICV) is calculated through an atlas normalization procedure. The surfacing algorithm uses intensity and continuity data, along with the correction of topological defects to generate a continuous cortical ribbon used to calculate gray matter volume and thickness, 27, 29, 33 a procedure validated against histological analysis34 and manual measurements.35 This cortical surface is then inflated and registered to a spherical atlas and parcellated into regions of interest based on the structure of gyri and sulci. 36 After processing through FreeSurfer version 5.1, each T1 was individually quality checked for accuracy of white and gray matter segmentation. Inaccuracies in white matter segmentation and pial surfaces were manually corrected using the built-in editing packages of FreeSurfer, and then reprocessed to calculate final volumetric measures.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistics package. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the three diagnostic groups. General linear model (GLMs) and Pearson’s Chi-Square test of Independence were used to investigate group differences in demographic variables. GLMs and linear mixed effects models controlling for education and CDR Total Score were used to test for between-group differences. Main-effects were compared using Sidak adjustment to confidence intervals, and interaction effects were analyzed by re-running the GLM comparing only the AD and bvFTD groups. We used a cutoff alpha level of .05 for all statistical tests.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. GLM showed that all three groups had comparable mean age (F (2, 72) = 2.6, p = .08) and MMSE scores between the two dementia groups were also similar (F (1, 48) = 1.3, p = .27). As expected, controls had significantly higher MMSE than dementia groups (F(2,72) = 24.3, p <.001). Significant group differences were found for education (F (2, 72) = 64.8, p < .001) and CDR Total Score (F (2, 72) = 3.4, p < .05). Post-hoc analyses revealed that controls had significantly more years of education than the bvFTD group but the AD group did not differ significantly from either. Total score on the CDR was significantly lower for controls than the AD group, which in turn was significantly lower than the bvFTD group. A Pearson’s Chi-Square test of Independence revealed no significant difference in proportion of males and females between the groups. Subsequent analyses therefore controlled only for education and CDR total score.

Table 1.

Demographics, California Verbal Learning Test-Short Form scores by group

| bvFTD | AD | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.7 (7.4) | 63.7 (8.6) | 65.6 (6.8) |

| Education | 15.7 (2.8) | 16.2 (2.6) | 17.5 (2.0) |

| MMSE | 25.7 (3.3) | 24.7(3.0) | 29.6 (0.6) |

| CDR Total Score | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| % male | 77% | 60% | 52% |

| Immediate Free Recall | 5.0 (1.9) | 3.4 (1.9) | 8.0 (1.2) |

| Delayed Free Recall | 3.9 (2.6) | 1.5 (1.9) | 7.6 (1.4) |

| Delayed Cued Recall | 4.3 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.0) | 7.9 (1.2) |

| Recognition d’ | 2.2 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.4) |

| Total Intrusion Errors | 2.3 (1.8) | 3.1 (3.8) | 1.0 (1.2) |

| Left Medial Temporal Lobe Volume | 6893.3 (1077.4) | 6540.6 (555.2) | 8021.4 (949.9) |

| Left Entorhinal Volume | 1351.2 (457.4) | 1342.6 (238.1) | 1902.6 (377.7) |

| Left Parahippocampal Volume | 1940.1 (335.0) | 1851.1 (301.0) | 2187.4 (341.4) |

| Left Hippocampal Volume | 3602.0 (585.1) | 3346.9 (329.9) | 3931.4 (509.8) |

| Right Medial Temporal Lobe Volume (composite) | 6127.4 (1115.8) | 6352.1 (518.0) | 7734.6 (944.6) |

| Right Entorhinal Volume | 1125.5 (458.7) | 1173.2 (262.4) | 1792.6 (371.2) |

| Right Parahippocampal Volume | 1613.9 (316.8) | 1728.9 (313.0) | 2034.8 (285.4) |

| Right Hippocampal Volume | 3388.0 (731.0) | 3450.0 (329.9) | 3907.2 (625.7) |

Note. AD= Alzheimer’s disease; bvFTD= behavioral variant Frontotemporal dementia; MMSE= Mini-Mental State Exam total score

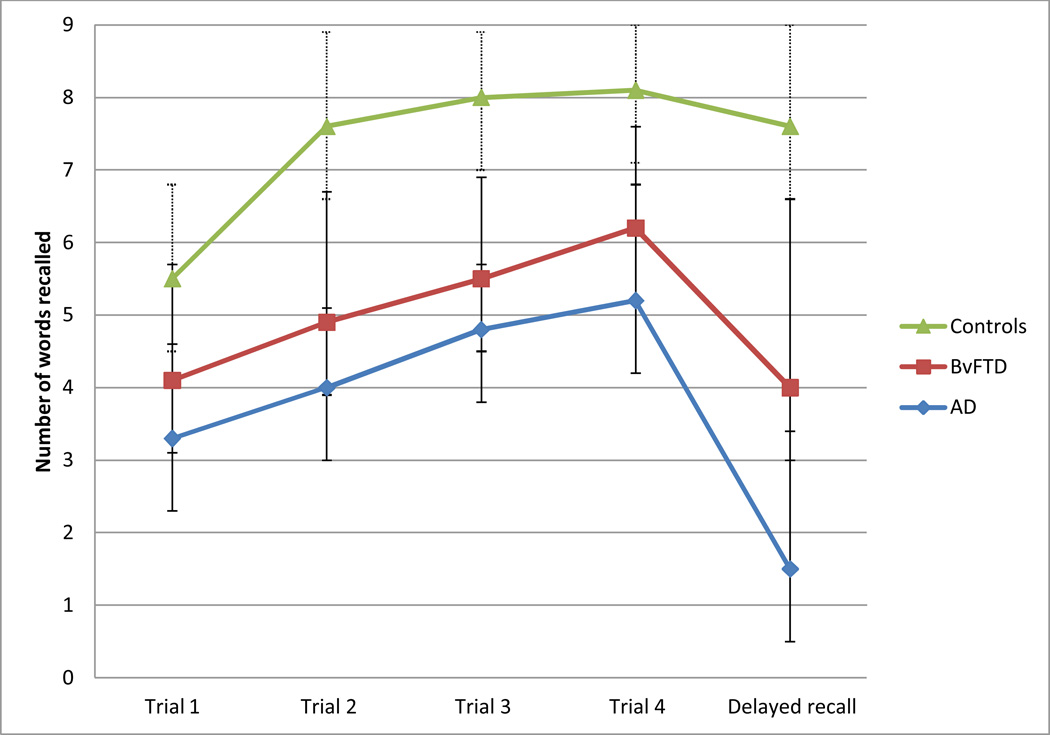

In terms of performance across the four learning trials, GLM revealed a main effect for diagnostic group (F (2, 70) = 23.6, p < .001) with controls demonstrating significantly better learning than bvFTD participants, who performed significantly better than AD participants (p<.05). The trial by group interaction was also significant (F (6, 210) = 3.2, p < .01), with controls improving their recall across trials at a faster rate than both AD and bvFTD groups, who had similarly low rates of improvements across trials (AD vs. bvFTD; F (3, 138) =0.5, p = .70).

Our hypothesis about consolidation was tested by comparing performance on the last learning trial (trial 4) with the 10-minute delayed free recall trial. Again, a main effect for group was significant (F (2, 70) = 39.1, p < .001), with controls recalling more words than bvFTD participants, and bvFTD participants recalling more words than AD participants (p<.002). The interaction term reflecting forgetting between learning and recall trials was also significant (F (2, 70) = 11.7 p < .001): AD participants showed a greater decline in words correctly recalled over the delay than bvFTD, and bvFTD participants showed a greater decline over the delay than controls.

The diagnostic utility of list retention was examined by calculating a percent retention score (delayed recall/best learning trial) and using logistic regression to see how well it classified the two groups. Overall classification was only 72.5%, with 76.9 % of AD participants and 68.0% of bvFTD participants correctly classified.

We then investigated the hypothesis that the bvFTD group would benefit more from cueing and recognition formats. When comparing free recall with cued recall, the main effect for group was significant (F (2, 70) = 37.6, p < .001), with controls performing significantly better than the bvFTD group who performed better than the AD group (p<.002). Neither the main effect for cueing nor the group by trial interactions were significant (F (1, 70) = .00, p =.95 and F (2, 70) = 2.5, p= .10, respectively), with all three groups showing similarly small improvements in correct responding with cueing. When comparing free recall versus correct recognition, there was a significant main effect of group (F (1, 64) = 32.7, p < .001), with controls recognizing more words than both patient groups and bvFTD participants recognizing more words than AD participants. The interaction effect was not significant (F (2, 64) = 2.9, p = .60), indicating that both groups displayed similar changes in performance with recognition.

Regarding the hypothesis that bvFTD participants would commit more intrusion errors than AD participants, GLMs revealed no significant main effects by group (F (2, 70) = 1.0, p= .37) or trial (F (1, 70) = 1.1, p= .23), and no interaction effects (F (2, 70) = 0.3, p= .65).

Most models of memory posit that the group differences in consolidation are attributable to differences in medial temporal structures. We tested this hypothesis by looking at medial temporal lobe (MTL) volumes in a subset of participants who underwent structural MRI within 6-months of their memory testing and whose scans were of sufficient quality to yield Freesurfer volumes. Imaging data was available for all normal controls, 14 AD participants (mean age=62; MMSE=25.0; CDR=0.8; 46% female) and 13 bvFTD participants (mean age=62.9; MMSE=26.21; CDR= 0.9; 28% female). We compared brain volumes for both the left and right hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus (see Table 1). We also compared gross MTL volume, which was a composite area including the aforementioned areas. Analyses found significant group differences for all of these brain areas ( p<.05). Post-hoc analyses revealed that controls had significantly larger volumes for all of these areas than the AD and bvFTD participants, with no significant differences in any of these areas between the patient groups.

We also used multiple regression to examine the relative contributions of the medial temporal areas and frontal regions to consolidation to test the hypothesis that memory consolidation in our AD and bvFTD groups might be mediated by different brain regions.37 Our small sample sizes required us to minimize the number of predictor variables, so we used bilateral medial temporal volumes (sum of both the left and right hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus) and a variable for the bilateral prefrontal areas most implicated in bvFTD (sum of the bilateral orbital-frontal, dorsolateral, ventromedial and anterior cingluate areas). Our criterion variable was delayed free recall, and we entered initial learning and intracranial volume in the first step, and medial temporal and frontal volumes in the second step. We ran separate models for AD and bvFTD. Results of our regression analyses for the AD group showed that the brain volumes explained an additional 34.7% of the variance in delayed recall, but that only the bilateral MTL volume was a significant predictor (β=.66, p=.05). Similar results were found for the bvFTD group: adding the brain regions in the second step of the model explained an additional 32.4% of the variance, and only the MTL volume was a significant predictor (β=.56, p<.05).

Discussion

A major finding of this study is that participants with bvFTD showed better consolidation of information over delays than participants with AD. This better consolidation is reflected in better recall of information after delays, after controlling for levels of immediate recall. Few studies have directly compared consolidation (or rate of forgetting; see Wicklund38). Instead most have looked at level of performance on learning and recall trials which can obscure important differences in pattern of performance. We also found that our bvFTD patient group outperformed AD patients in terms of mean score across CVLT-SF trials, which replicate certain studies 4–6 and differs from others.7,8 However, given the current inconsistent findings regarding level of performance comparisons, we suggest that moving towards analysis of patterns of performance (or performance changes across trials) may result in clearer and more consistent findings across studies.

It is important to note that despite the finding of significantly poorer consolidation in AD participants, we found that using the percentage of words retained to differentiate performance between the two groups achieved only modest classification and therefore had limited diagnostic utility in isolation. Other analyses also revealed considerable overlap in the pattern of performance on learning, benefit from cued recall and benefit from recognition format with both patient groups demonstrating comparable changes. These results highlight the considerable overlap in memory performance between these groups and the difficulty in using memory performance alone to diagnostically differentiate between them. Indeed, in their metanalytic review, Huthinson and Mathias4 state that “performance of AD and FTD participants did not differ significantly on a large range of tests” and “even when the most discriminating cognitive tests are used, the differential diagnosis of AD and FTD remains problematic” (p.924).

Embedded in these results is our finding that the bvFTD participant group did not conform to our hypothesized pattern of dysexecutive performance. Relative to AD participants, they did not commit more intrusion errors nor did they benefit more from cueing or recognition format. These hypotheses were based on the theorized influence of the frontal lobes in error monitoring and search and retrieval in memory processes. However, support for this literature is generally derived from studies of participants with focal frontal impairment10 or comparisons between participants with frontal pathology and healthy controls.11 Thus, our finding that both AD and bvFTD participants committed similar numbers of intrusions, and that neither showed much benefit from cues or recognition format, may reflect the diffuse brain pathology leading to impairments in the memory processes of both our dementia groups. Alternatively, it is possible that the CVLT-SF is not sensitive enough to dysexecutive performance.

Although the AD group showed poorer consolidation than the bvFTD group, and consolidation is presumably mediated by the medial temporal lobes, there were no significant differences in MTL volumes between AD and bvFTD. We suggest two possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, volumetric data was only available on a subset of subjects, so our analysis had limited power. Of note, however, is that these results replicate the findings of others who have also shown considerable overlap in hippocampal and other MTL area volumes between bvFTD and AD.37,39 A second and more likely explanation is that the two dementia groups may differ in which subregions of the hippocampus are affected7. Using Freesurfer to measure medial temporal volumes will overlook these anatomical differences.

Additional analyses looking at the relative contributions of the frontal lobes and MTL areas to memory consolidation found only bilateral MTLs to be a significant predictor, again replicating established literature reflecting the high correlation between consolidation and MTL. It is important to note that our findings are not necessarily inconsistent with those of higher correlation between memory performance and frontal areas in bvFTD participants.37 Pennington et al. looked at memory scores and not consolidation, per se.

Clearly, memory impairments in bvFTD is controversial and has important implications for both clinical work and research. Our study adds to a growing body of literature which, acknowledging the shortcomings of purely clinical diagnoses, has begun comparing the memory profiles of bvFTD and AD patients with pathology confirmed or biomarker-supported diagnoses. Our study also drew the distinction between level and pattern of performance and explicitly addressed both types of performance. We also explored the neuroanatomical correlates of consolidation in these two groups.

Further studies should seek to extend our understanding of memory profiles by examining memory performance for more organized information, such as story memory, as well as memory for visual information which are hypothesized to have different loads on executive functioning.40 Additionally, examining performance on measures that directly assess executive functions may also further clarify performance differences. The role of other limbic structures, such as the retrosplenial cortex may also be important to further understanding of memory performance in these groups. Finally, it would also be interesting to examine clinicopathological groups of bvFTD in order to identify whether FTLD pathology subtypes conform to distinct memory performance patterns.

Figure 1.

CVLT-SF performance on learning and delayed recall trials by diagnostic group.

Footnotes

Statistical analyses were completed by Dr. Mansoor at Medstar National Rehabilitation, and Dr. Kramer, Mr. Dutt and Ms. Jastrzab at University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center. This study did not have any sponsor.

Dr. Mansoor is the corresponding author and was involved in study conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript. She reports no disclosures.

Ms. Jastrzab is an author involved in data analysis and interpretation as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. She reports no disclosures.

Mr. Dutt is an author who was responsible for collecting and processing brain imaging data. He reports no disclosures.

Dr. Miller is an author who was involved in study conceptualization, data collection and interpretation, as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. He reports the following disclosures: Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Study (DSMB) scientific advisory board, editor of Neurocase in 2003 and associate editor of ADAD in 2009, publishing royalties for Behavioral Neurology of Dementia, Cambridge 2009, Handbook of Neurology, Elsevier 2009 and The Human Frontal Lobes, Guilford, 2008, consultancy with Allon Pharmaceutircals - Steering Committee AL-108-231, Bristol-Myers Squibb - PSP SAB, TauRx - SAB bvFTD Trial, Siemens Molecular Imaging, Neurology SAB, Ely Lilly, US AD Advisory Board and Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Inc., commercial research support from Novartis Research Grant, governmental research support for NIA P50 AG23501 PI, 2004-present, NIA P01 AG19724 PI, 2002-present, and State of California Alzheimer's Center PI 1999-present.

Dr. Seeley is an author who was involved in study conceptualization, pathology analysis and interpretation, as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. He reports the following disclosures: scientific advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Annals of Neurology editorial board member, consultancy with Summer Street Research Partners, governmental research support for National Institute on Aging, AG033017, PI, 2009–2014, National Institute on Aging, AG023501, 2009–2014, and National Institute on Aging, AG023501, involvement in John Douglas French Alzheimer's Disease Foundation, Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, Tau Consortium, James S. McDonnell Foundation, Alzheimer's Disease Drug Foundation and Association for Frontotemporal Dementia.

Dr. Kramer is an author involved in study conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. He reports the following disclosures: publishing royalties for the California Verbal Learning Test, Pearson, Inc. 2001 and NIH grant R01AG022983.

Contributor Information

Y Mansoor, MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital

L Jastrzab, Email: ljastrzab@memory.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center.

S Dutt, Email: sdutt@memory.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center.

BL Miller, Email: bmiller@memory.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center.

WW Seeley, Email: wseeley@memory.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center.

JH Kramer, Email: jkramer@memory.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center.

References

- 1.Frisoni GB, Beltramello A, Geroldi C, Weiss C, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M. Brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1996;61:157–165. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavenu I, Pasquier F, Lebert F, Pruvo JP, Petit H. Explicit memory in frontotemporal dementia: the role of medial temporal atrophy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9:99–102. doi: 10.1159/000017030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varma AR, Snowden JS, Lloyd JJ, Talbot PR, Mann DM, Neary D. Evaluation of the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria in the differentiation of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:184–188. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson AD, Mathias JL. Neuropsychological deficits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analytic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:917–928. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidler-Gary J, Gottesman R, Newhart M, Chang S, Ken L, Hillis AE. Utility of behavioral versus cognitive measures in differentiating between subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23:184–193. doi: 10.1159/000098562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertoux M, de Souza LC, Corlier F, et al. Two distinct amnestic profiles in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornberger M, Piguet O, Graham AJ, Nestor PJ, Hodges JR. How preserved is episodic memory in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia? Neurology. 2010;74:472–479. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cef85d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irish M, Piguet O, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Common and unique grey matter correlates of episodic memory dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Human Brain Mapping. 2014;35:1422–1435. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldo JV, Shimamura AP. Frontal lobes and memory. In: Baddeley A, Wilson B, Kopelman M, editors. Handbook of Memory Disorders. 2nd ed. London: John Wiley & Co; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neary D. Neuropsychological aspects of frontotemporal degeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;769:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb38128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler MA, Stuss DT, Tulving E. Frontal lobe damage produces episodic memory impairment . J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1:525–536. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathologica correlations. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:952–962. doi: 10.1002/ana.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovici GD, Seeley WW, Kim EJ, et al. Distinct MRI atrophy patterns in autopsy-proven Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22:474–488. doi: 10.1177/1533317507308779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease . J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, O'Neil JP, et al. 11C-PIB PET imaging in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2007;68:1205–1212. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259035.98480.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the mental state of patients for the clinician . J Psychiat Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current ver sion and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test. Second ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischl B, Liu A, Dale AM. Automated manifold surgery: constructing geometrically accurate and topologically correct models of the human cerebral cortex. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:70–80. doi: 10.1109/42.906426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segonne F, Dale AM, Busa E, et al. A hybrid approach to the skull stripping problem in MRI. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1060–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segonne F, Pacheco J, Fischl B. Geometrically accurate topology-correction of cortical surfaces using nonseparating loops. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:518–529. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.887364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosas HD, Liu AK, Hersch S, et al. Regional and progressive thinning of the cortical ribbon in Huntington's disease. Neurology. 2002;58:695–701. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuperberg GR, Broome MR, McGuire PK, et al. Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:878–888. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage. 2010;53:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennington C, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Neural correlates of episodic memory in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. J of Alzheimer’s disease. 2011;24:261–268. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wicklund AH, Johnson N, Rademaker A, Weitner BB, Weintraub S. Word list versus story memory in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:86–92. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213811.97305.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Souza LC, Chupin M, Bertoux M, et al. Is hippocampal volume a good marker to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from frontotemporal dementia? J of Alzheimer’s disease. 2013;36:57–66. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busch RM, Booth JE, McBride A, Vanderploeg RD, Curtiss G, Duchnick JJ. Role of executive functioning in verbal and visual memory. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:171–180. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]