Abstract

The aim of this preliminary case study series was to investigate epidermal innervation in pediatric patients with significant neurological impairment and self-injurious behavior. We enrolled four pediatric patients with self-injury (two males, two females; mean age 12y, range 9–14y) and used archival specimens from healthy, age-matched children with typical development for comparison purposes. Epidermal nerve fiber density, peptide content, and mast cell degranulation patterns from non-damaged skin were tested between the patients and the comparison group. The male patients with self-injury had significantly increased epidermal nerve fiber densities, increased substance P positive fiber count and extensive mast cell degranulation compared with sex- and age-matched individuals with typical development. Our case series shows for the first time altered peripheral innervation from non-damaged tissue in children with significant self-injury and developmental disability compared with a healthy comparison group. Establishing the role of peripheral nociceptive and immune modulatory neural pathways may offer new treatment avenues for this devastating neurobehavioral disorder.

Self-injurious behavior (SIB) is among the most destructive and costly forms of behavioral pathology observed in children with severe neurological impairment associated with developmental disorders.1 In almost all cases of SIB the pathogenesis is unknown and the underlying pathophysiology is only partly understood. It has been hypothesized, but never directly tested in pediatric samples, that abnormal sensory function may be a contributing factor to self-injury. Part of the rate-limiting step in clinical investigations of children with self-injury and developmental disability is comorbid intellectual and communicative impairment, making it almost impossible to reliably and validly assess sensory function behaviorally (e.g. quantitative sensory testing or related approaches). Previously it was shown in adults with chronic SIB and severe neurological impairment that peripheral cutaneous innervation by epidermal nerve fibers (ENF) was substantially altered and correlated with observed cutaneous sensory reactivity.2,3 Altered pain and sensory sensitivity is associated with morphological and functional changes in cutaneous ENFs in a variety of clinical conditions. 4,5,6 Here we report the first investigation of peripheral innervation from four pediatric chronic SIB cases using epidermal punch biopsies.

Case Report

Case Reports

Four children (two males, two females; mean age 12y range 9‐14y) with severe (two) and profound (two) neurological impairment and associated neurodevelopmental disability and histories of chronic tissue damaging self-injury (forceful contact of closed fist with the head or face and biting associated with surface trauma marked by breaks in the skin, tissue rupture, and scarring) were recruited. The SIB cohort was a convenience sample recruited through a pediatric tertiary clinic with patients with developmental delays screened for SIB (parent report) and then parental consent to participate. Each child had (1) a functional diagnosis of severe/profound intellectual disability (based on DSM IV criteria and standard intellectual and adaptive behavioral test results as documented through existing chart review); (2) exhibited chronic SIB (present for at least 12mo) occurring either hourly or at least daily in bouts or discrete episodes (based on parent or teacher report and corroborated through direct observation); (3) received treatment for SIB that was currently stable (not planned on being changed in the next month, Table I lists the active medication status; all four individuals were mechanically restrained for various periods of time during their waking hours); and (4) parent/guardian informed consent. Each individual was in overall good general health with no known serious unmanaged accompanying acute health impairments considered to be painful (e.g. chronic reflux or otitis media as determined by patients' physician record review and/or examination if necessary) or specific syndromes associated with SIB (e.g. Lesch-Nyan syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome). Eleven children of similar ages (9–14y, six males, five females) with no history of self-injury, cognitive impairment, or systemic disease made up a ‘healthy comparison’ (no disability) group for age and sex normative comparisons based on archival biopsy specimens.

Table I. Density, spacing, and neuropeptide content of self-injurious behavior (SIB) and control biopsies.

| Leg (postero-medial calf) biopsy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Participants(M/F age in years) | ENF(ENF/mm) | SP | MC | CGRP | VIP |

| SIB 1(M, 9) | 65 | 6 | - | 0 | 0 |

| SIB 2(M, 12) | 46 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| SIB 3(F, 14) | 46 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| SIB 4(F, 13) | 29 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Comp 1 (M, 11) | 36 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comp. 2(M, 13) | 22 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comp. 3(F, 16) | 21 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Comp. 4(F, 12) | 26 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Medication status: SIB 1, amitriptyline, diazepam, gabapentin; SIB 2, ibuprofen, gabapentin; SIB 3, carbamazepine, omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate, leuprolide acetate; SIB 4, quetiapine. ENF, epidermal nerve fiber density; SP, substance P; MC, mast cell degranulation score; CRGP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; M, male; F, female.

Skin biopsy

Following institutional review board approval from the University of Minnesota Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, single punch skin biopsies were obtained from the postero-medial calf (a site with no skin damage, no SIB) to compare directly with the same normative samples from approximate age-matched, body-site matched comparison children without developmental disability. Body sites were anesthetized by intradermal injection of 1% xylocaine or the application of a topical anesthetic and the biopsy was made with a 3mm punch tool (Aucpunch; Acuderm; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA).

Biopsies were processed using previously established and described techniques.4 All specimens were fixed with Zamboni's solution and processed for immunofluorescent localization of nerve and tissue antigens.4 ENFs were traced, from confocal images, using Neurolucida software (MicroBrightField, Colchester, VT, USA) according to established counting criteria and reported as the number of ENFs per millimeter in a 50μm-thick section.5 The primary outcomes measures for analyses were ENF density, substance P positive fiber count, and mast cell degranulation. Mast cell degranulation was scored: 0=no degranulation, 1=degranulation limited to deep dermis, 2=degranulation limited to deep and mid dermis, 3=degranulation throughout tissue, and 4=extensive degranulation throughout tissue.

Case specimen analysis and findings

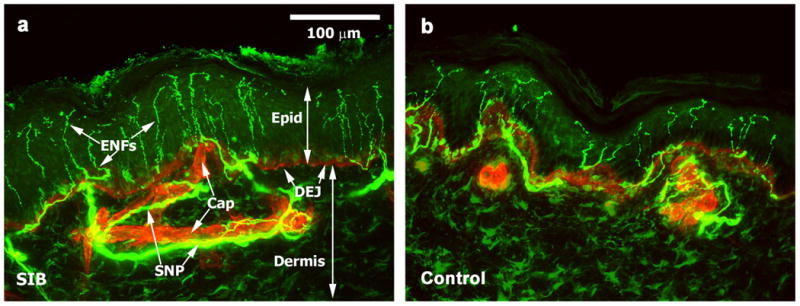

Visual microscopic examination and qualitative analyses of the four SIB cases revealed that, relative to non-disabled comparison individuals, there appeared to be an almost twofold increase in ENF density in some of the SIB cases. Based on confocal imaging and quantitation for the group, the mean ENF density for the four SIB cases was statistically marginally greater (t4 = 2.25, p = 0.054) at 46.5 fibers/mm (SD 14.71,) than the 30.3 fibers/mm (SD 6.85) for healthy comparison individuals in 50μm-thick sections taken from the leg (see Fig. 1 for representative innervation images). Because there is some evidence that SIB is more prevalent in males than females,1 sex differences were examined. The ENF density values for the two males with SIB (mean 55.54, SD 13.3) were significantly greater than their healthy peers (mean 20.08, SD 10.9; t3 = 3.16, p = 0.024); the difference between females was not statistically significant (p 0.49).

Figure 1.

Confocal images of epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs) in skin in children with and without self-injurious behavior (SIB). (a) Nerve, protein gene product 9.5 immunolocalization, (green) distribution in superficial skin of a representative pediatric SIB case. Basement membrane, type IV collagen immunolocalization (red), reveals capillaries (Cap) and the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) that separates the epidermis (Epid) from deeper dermis. ENFs were counted as they crossed the DEJ. Epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs) arising from the sub-epidermal neural plexus (SNP) are abundant (1.3 times more ENFs than comparison, on average). The density for this individual was 65 ENFs/mm. (b) Comparison skin sample with typical normal innervation pattern. ENF density for this participant was 26 ENFs/mm. Thickness of epidermis may vary from individual to individual regardless of disease state. Scale bar = 100 μm for all images.

Substance P-positive fiber density in the subepidermal nerve plexus was increased with two to three times as many fibers in the SIB group as the comparison group (of the typical individuals from whom we had peptide analysis and mast cell staining available [n=4, age 11–14y, three males with no history of self-injury, cognitive impairment or systemic disease]; Table 1).

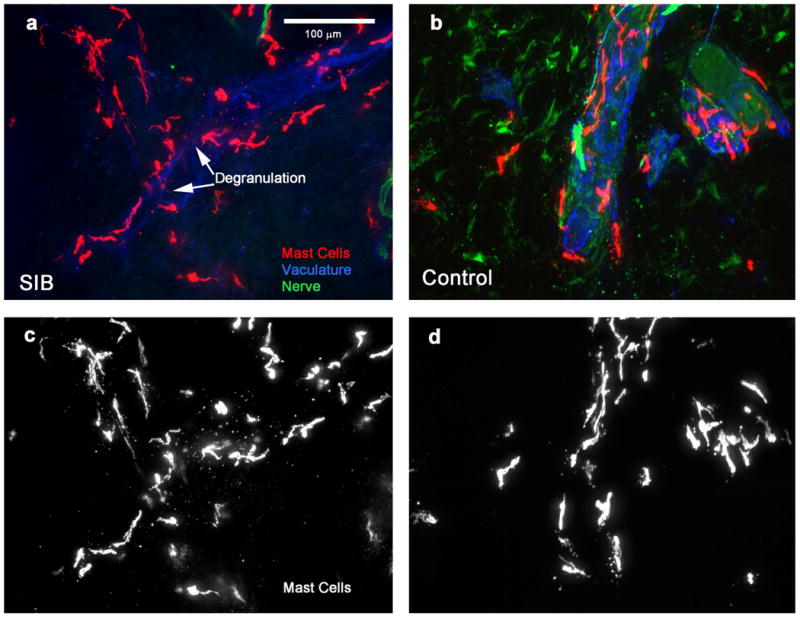

Biopsies were scored for mast cell degranulation in three of the four SIB patients (see Fig. 2 for representative images). Mast cell degranulation was readily apparent in the SIB cases compared with the comparison group. Two cases had degranulation throughout the tissue and one had extensive degranulation throughout the tissue. Of the comparison group, two had no degranulation, one had minimal degranulation limited to the deep dermis, and one had minimal degranulation limited to the deep and mid dermis.

Figure 2.

Mast cells in skin of children with and without self-injurious behavior (SIB). Mast cells (tryptase immunolocalization, red in color images a and b, white in gray scale images (c and d) in mid dermis of SIB (a and c) and comparison (b and d) pediatric participants. Nerves (green) and vasculature (blue) are also shown in color images. Mast cells tend to aggregate around vessels. Mast cells in SIB pediatric cases appeared to be similar in number as compared with healthy comparison individuals, but degranulation was observed throughout the dermis of pediatric SIB cases, whereas degranulation was rarely seen in comparison cases. Medication status across the four participants varied and there was no reason to think that the different classes of medications would lead to widespread mast cell degranulation. The available, albeit limited, preclinical evidence is that traditional antipsychotics inhibit mast cell degranulation in the dermis – presumably atypical neuroleptics (of which some of the children were prescribed or had a history with) would have similar inhibitory, if any, effects in epidermis but this is unknown. The observed degranulation in our samples is in the direction opposite to that of the expected effect that neuroleptics would have; so too with gabapentin which may exhibit analgesic or possible antipruritic effects which would be in the opposite direction to inducing degranulation. There were no histamine specific compounds used for treatment and no reason to suspect any of the participants were experiencing any sort of allergic reaction at the time of the biopsy. Skin samples from leg (postero-medial calf). Scale bar = 100 μm for all images.

Discussion

These initial results from four children with self-injury are the first to document altered peripheral innervation in a pediatric sample with significant neurological impairment associated with intellectual disability. Particularly important is that the differences were obtained from undamaged tissue at body sites not targeted for injury. There are several issues raised by the study outcomes. The first concerns the underlying peripheral/central control mechanisms regulating the early development and guided growth for small unmyelinated fibers in the periphery.7 Perturbations to the regulatory elements may have profound sensory consequences. An obvious candidate molecule is nerve growth factor, which is important in fetal development because it ensures the survival of the peptidergic cells and during neonatal development nerve growth factor is involved in ensuring that the typical nociceptor phenotype emerges.8 There has been no investigation of nerve growth factor in relation to SIB in this population.

There are several limitations worth noting and consistent with a case series. Whether the four cases are representative of all pediatric SIB cases is unknown and unlikely. But, it would suggest the likelihood that some SIB cases may be subgrouped, perhaps, by degree of mast cell involvement or ENF density values which may be relevant for understanding treatment outcomes and variability in the disorder. The sample size was small but given the invasive nature of the procedure and a vulnerable population, we considered this investigative. Similarly, the statistical analysis is more accurately interpreted as descriptive and sample specific rather than confirmatory.

Although the findings are limited to a single time point and thus do not permit a dynamic interpretation, it is worth speculating about the likelihood of some degree of neuro-immune ‘cross-talk’ occurring in our samples that may contribute to altered sensory function associated with self-injury. Increased ENF innervation density results in increased substance P positive fibers, which in turn is likely to contribute to the extensive mast cell degranulation.9 Mast cell degranulation results in the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the area and the release of inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6) as well as additional ENF sensitizing agents histamine, serotonin, ATP, trypsin, and tryptase.10 The net effect of such a cascade would result in sensitizing the ENFs and further upregulating the release of substance P to drive an inflammatory-nociceptive cycle. Considered this way, and if it were possible to confirm this cascade of events, a new clue to treating SIB in this population, or more likely, a subgroup of SIB cases, may be in disrupting such an inflammatory-nociceptive cycle. Although speculative, our novel observations suggest further comparable work is warranted to address an otherwise often intractable and desperate clinical problem.

What this paper adds.

Degranulated mast cells can be found throughout the dermis from non-self-injury body sites of children with neurodevelopmental disability and self-injury.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by NIH Grants HD44763 and HD35682. The funder played no part in study design, data collection or data analysis for this study and was not involved in the preparation of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Abbreviations

- ENF

Epidermal nerve fibers

- SIB

Self-injurious behavior

References

- 1.Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Berkson G, et al. Self-injurious behavior: Gene-brain-behavior relationships. Ment Retard Dev Dis Res Rev. 2001;7:3–12. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(200102)7:1<3::AID-MRDD1002>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Symons FJ, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy W, Heeth W, Bodfish JW. Degranulated mast cells in the skin of adults with self-injurious behavior and neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Symons FJ, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy W, et al. Evidence of altered epidermal nerve fiber morphology in adults with self-injurious behavior and neurodevelopmental disorders. Pain. 2008;134:232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy WR, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Johnson T. Quantification of epidermal nerves in diabetic neuropathy. Neurology. 1996;47:1042–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy WR, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Polydefkis M, McArthur J. Pathology and quantitation of cutaneous nerves. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005. pp. 869–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy BG, Hsieh ST, Stocks A, et al. Cutaneous innervation in sensory neuropathies: Evaluation by skin biopsies. Neurology. 1995;45:1848–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.10.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice FL, Albers KM, Davis BM, et al. Differential dependency of unmyelinated and A delta epidermal and upper dermal innervation on neurotrophics, trk receptors, and p75LNGFR. Dev Biol. 1998;198:57–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albers KM, Wright DE, Davis BM. Overexpression of nerve growth factor in epidermis of transgenic mice causes hypertrophy of the peripheral nervous system. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1422–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewin GR, Mendell LM. Nerve growth factor and nociception. TINS. 1993;16:353–9. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moalem G, Tracey DJ. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:240–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]