Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to develop and validate methods for analyzing wrist accelerometer data in youth.

METHODS

181 youth (mean±SD; age, 12.0±1.5 yrs) completed 30-min of supine rest and 8-min each of 2 to 7 structured activities (selected from a list of 25). Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves and regression analyses were used to develop prediction equations for energy expenditure (child-METs; measured activity VO2 divided by measured resting VO2) and cut-points for computing time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light (LPA), moderate (MPA), and vigorous (VPA) physical activity. Both vertical axis (VA) and vector magnitude (VM) counts per 5 seconds were used for this purpose. The validation study included 42 youth (age, 12.6±0.8 yrs) who completed approximately 2-hrs of unstructured PA. During all measurements, activity data were collected using an ActiGraph GT3X or GT3X+, positioned on the dominant wrist. Oxygen consumption was measured using a Cosmed K4b2. Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare measured vs predicted child-METs (regression only), and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA.

RESULTS

All ROC cut-points were similar for area under the curve (≥0.825), sensitivity (≥0.756), and specificity (≥0.634) and they significantly underestimated LPA and overestimated VPA (P<0.05). The VA and VM regression models were within ±0.21 child-METs of mean measured child-METs and ±2.5 minutes of measured time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA, respectively (P>0.05).

CONCLUSION

Compared to measured values, the VA and VM regression models developed on wrist accelerometer data had insignificant mean bias for child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA; however they had large individual errors.

Keywords: MOTION SENSOR, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, OXYGEN CONSUMPTION, ACTIVITY COUNTS VARIABILITY

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of physical activity (PA) for youth have been well documented. In order for these benefits to be studied in more detail, there is a need for accurate assessments of PA. Self-report assessments of PA are commonly used, but they are limited in their accuracy. Accelerometers are increasingly being recognized as a practical tool for objective PA measurement. Accelerometers are used in both laboratory- and clinical-based studies, as well as population-based surveillance studies including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) (21). Recently, there has been a movement away from the traditional placement of accelerometers on the hip, to locations such as the wrist (5,7,12,15). Advantages to the wrist location include increased wear time compliance and the ability to assess sleep. However, there is a lack of information, especially for the ActiGraph accelerometer, on how to use wrist accelerometer data to predict energy expenditure, and time spent in PA intensities.

In adults, a variety of monitors have been used to develop regression equations relating counts to energy expenditure for several different wear locations (e.g., wrist, hip, ankle) (10,13,20). These regression equations are commonly used to develop cut-points for time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB; < 1.50 METs (multiples of resting metabolic rate)), light PA (LPA; 1.50–2.99 METs), moderate PA (MPA; 3.00–5.99 METs), and vigorous PA (VPA; ≥ 6.00 METs). However, these studies show that there is a large variation in the relationship between counts and energy expenditure that is not consistent between placement sites, thus requiring each location to have separate methods of predicting energy expenditure and PA intensity. Similar to studies in adults, a number of studies in children have used an ActiGraph worn at the hip site to establish regression equations and cut-points (2,6,14). However, only a few studies have addressed the wrist location. Specifically, the validity of algorithms for the Actical (1-axis; wrist) (7,17), Actiwatch (1-axis; wrist) (4), and GENEActiv (3-axis; wrist) (5,18) have been examined in the laboratory for children. Ekblom et al. (4) showed that the Actiwatch accelerometer counts were significant correlated with EE (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) and Schaefer et al. (18) demonstrated the ability of the GENEActiv to accurately classify SB and PA intensities.

Currently, there are three published articles that have used the wrist location with the ActiGraph in young children (15–36 months) (9) and adolescents (8,16). However, one of the studies in adolescents looked at activity classification using a combined wrist and hip algorithm (16), while the other study in adolescents used raw acceleration (8), which cannot be used with previously collected data utilizing counts. Thus, there is a need for accurate methods of converting the ActiGraph accelerometer counts, which are still widely used, into PA outcomes (e.g., energy expenditure, time spent in MVPA, etc.). Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to develop prediction models for estimates of energy expenditure and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA using the wrist accelerometer placement in youth using two methods: 1) Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) analyses, and 2) regression analyses. A secondary aim was to examine the validity of the developed youth wrist models in an unstructured PA setting (simulated free-living).

METHODS

Participants

Eighty-four girls and 97 boys between the ages of 8 and 15 yrs volunteered to participate in the study. Participants were recruited using flyers and word of mouth at elementary and middle schools and after school programs in the Boston, MA area. The procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Massachusetts Boston and Boston Public School Institutional Review Board before the start of the study. A parent/legal guardian of each participant signed a written informed consent and filled out a health history questionnaire, and each child signed a written assent prior to participation in the study. Participants were excluded from the study if they had any contraindications to exercise, or were physically unable to complete the activities. In addition, none of the participants were taking any medications that would affect their metabolism (e.g. Concerta or Ritalin).

Procedures

This study was part of two larger studies using the same participants and exercise protocols that were combined for the purpose of this study (2,3). Specifically, participants recruited for structured activity routines 1–3 (see below) were part of the first study and participants recruited for structured activity routine 4 and the unstructured PA were part of a second study. The overall study procedures consisted of two parts: 1) structured activities that were used for development of the wrist prediction models, and 2) unstructured PA measurement that was used to examine the validity of the developed prediction methods. All testing took place at GoKids Boston: Research, Training, and Outreach Center, located on the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston or at a Boston public school.

Structured Activity Routines

The structured activity routines (n=181) was performed over a 2-day period. Measurement days were separated by a minimum of 24 hours with a maximum of two weeks between the testing days. On day 1, participants had their anthropometric measurements taken and completed 30 minutes of supine rest in a quiet room for an estimate of resting metabolic rate (RMR). On day 2, participants performed various lifestyle and sporting activities that were broken into four routines. All participants performed the resting measurement and one of four physical activity routines. Routine one was completed by 38 participants (17 boys and 21 girls), and routines two and three were each completed by 37 participants (21 boys and 16 girls). Sixty-nine participants (38 boys and 21 girls) completed 2–7 activities in routine 4; however due to scheduling issues, not all participants completed all activities for the routine. Participants performed each activity in a routine for eight minutes, with a one to two minute break between each activity. Once eligibility was determined, participants completing routines 1–3 were randomly assigned to a routine based on their age, gender, and BMI, so that approximately equal numbers would complete each of the activities. Since routine 4 was part of a separate study, participants were recruited to complete that specific routine along with the unstructured PA (see below). Routine one included: reading, sweeping, Nintendo Wii, Floor Light Space, slow track walking (self-selected speed), and brisk track walking (self-selected speed). Routine two included: watching television, Wall Light Space, Dance Dance Revolution, playing catch, track walking with a backpack (self-selected speed), and soccer around cones. Routine three included: searching internet, vacuuming, Sport Wall, Trazer, workout video, track running (self-selected speed). Routine four included: computer games, board games, light cleaning, Jackie Chan video game, wall ball, walking a course around campus (self-selected speed), and running a course around campus (self-selected speed). All activities within a routine were performed in the order listed above; a detailed description of these activities can be found elsewhere (2,3).

Oxygen consumption (VO2) was measured continuously, using indirect calorimetry (Cosmed K4b2, Rome Italy). Simultaneously, activity data were collected using an ActiGraph GT3X (routines 1–3) or ActiGraph GT3X+ (routine 4) accelerometer positioned on the dominant wrist. Previous studies have used both the dominant and non-dominant wrist and there is not a clear consensus as to which to use. Thus, we chose the dominant wrist as we felt it would detect more of the activities performed requiring the dominant hand (e.g. sports and household chores) and provide a better overall estimate of energy expenditure. To account for the additional weight of the devices, 2 kg was added to the participant’s body weight. This was done for the calculation of measured energy expenditure values from the Cosmed, except for non-weight bearing activities (e.g. lying, computer play) where the additional weight of the devices would not influence the energy cost to perform the activity.

Unstructured PA Measurement

Children participating in routine four were asked to return for a third day of measurement which consisted of approximately two hours of unstructured PA (n=41), which was meant to simulate free-living activity. Briefly, a research assistant was with the child at all times during the unstructured PA measurement, but did not communicate with the child or instruct them what to do. During water and bathroom breaks, if needed, the Cosmed mask was removed, resulting in a loss of data. Thus, time periods when the breaks occurred were removed from the analysis. All testing took place at University of Massachusetts Boston or the school the participant attended. During the measurement period participants interacted with other youth who were not part of the measurement, allowing for a more realistic setting. Example activities during the unstructured PA measurement included: SB (e.g., watching movies, reading, homework), active games (e.g., Dance Dance Revolution and Nintendo Wii), and recreational activities (e.g., soccer, basketball, lifting weights) (see Crouter et al. for further detail (3)). Oxygen consumption and activity data (GT3X+) were collected in the same manner as the structured activities.

Anthropometric measurements

Prior to testing, participants had their height and weight measured (in light clothing, without shoes) using a stadiometer and a physician’s scale, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the formula: body mass (kg) divided by height squared (m2) and gender- and age-specific BMI percentiles were calculated using CDC algorithms (1).

Indirect calorimetry

A Cosmed K4b2 was used to measure oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production during each activity routine and unstructured PA measurement. Prior to each test the oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers were calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This consisted of: 1) room air calibration, 2) reference gas calibration using 15.93% oxygen and 4.92% carbon dioxide, 3) flow turbine calibration using a 3.00 L syringe (Hans-Rudolph), and 4) a delay calibration to adjust for the lag time that occurs between the expiratory flow measurement and the gas analyzers.

ActiGraph accelerometer

The ActiGraph GT3X (3.8 × 3.7 × 1.8 cm; 27 grams) and ActiGraph GT3X+ (4.6 × 3.3 × 1.5 cm; 19 grams) tri-axial accelerometers were used for activity measurement. The GT3X was used in the first study (structured activity routines 1–3) and prior to starting the second study (structured routine 4 and unstructured PA) the GT3X+ was released and was used for the second study. The GT3X and GT3X+ measure accelerations in the range of 0.05 to 2 G’s and ± 6 G’s, respectively. The acceleration data is digitized by a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter and the data is filtered using a band limited frequency of 0.25 to 2.5 Hz. These values correspond to the range in which most human activities are performed. Once the raw data are downloaded, the ActiLife software can be used to convert the raw data to a user specified epoch (e.g. 10 sec). During all testing the GT3X or GT3X+ was worn on the dominant wrist, attached using a nylon belt designed specifically for the wrist. The GT3X and GT3X+ were initialized using 1-second epochs and 30 Hz, respectively, and the low frequency extension turned on. The accelerometer was positioned on top of the wrist, proximal to the ulnar styloid process, so that the vertical axis (VA; x-axis) of the ActiGraph was parallel to the longitudinal axis of the lower arm. The accelerometer time was synchronized with a digital clock so the start time could be synchronized with the Cosmed K4b2. At the conclusion of the test the accelerometer data were downloaded for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

Breath-by-breath data were collected using the Cosmed K4b2, which was averaged over a one minute period for the structured activities and a 15-sec period for the unstructured PA. The VO2 (ml·min−1) was converted to VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1). To account for higher resting metabolic rates in children compared to adults (11,19) child-METs were calculated by dividing the VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) for each by the participant’s supine resting VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1). For each structured activity, the child-MET values for minutes 4 to 7 were averaged and used for the subsequent analysis. The entire unstructured PA measurement period was used with the exception of times when the mask was removed for water or bathroom breaks. The raw ActiGraph accelerometer data for each axis and the mean vector magnitude (VM; square root of the sum squared activity counts from each axis) were converted to counts per 5 seconds.

Statistical treatment

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS version 21.0 for windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). For all analyses, an alpha level of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. All values are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Using the structured physical activities (routine 1–4), two statistical approaches were utilized for the development of the prediction models. First, cut-points were developed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. ROC was used to determine the best threshold for detecting SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. For SB, MPA, and VPA cut-points the ROC curve was developed by coding the measured child-MET values as zero or one. The SB and MPA cut-points were used as the lower and upper cut-point for LPA. Second, regression analyses were used to develop regression equations relating activity counts and energy expenditure (child-METs). The regression analyses used the VM and VA to relate the accelerometer 5-sec counts to measured child-METs. In addition, the mean counts and percentile distribution were used to determine an inactivity threshold for SB (e.g., lying, reading, and video watching).

One-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare measured (Cosmed) and predicted child-METs (regression models only) for the unstructured PA. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to compare measured and predicted (regression models and cut-points) time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA during the unstructured PA. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments were performed to locate significant differences, when necessary.

Measured and predicted child-METs were used to calculate root mean squared error (RMSE; square root of the mean of the squared differences between the prediction and the criterion measure), mean bias, and 95% prediction intervals (95%PI) for the unstructured PA measurement PA outcomes. The use of RMSE allows for the examination of the precision of a prediction equation, with a lower RMSE indicating a more precise estimate.

RESULTS

Data for four participants who performed the structured activities and two participants who completed the unstructured PA were excluded due to accelerometer malfunction resulting in data loss.

Participant descriptive characteristics are shown in table 1. Mean (SD) measured child-MET values, wrist ActiGraph counts per 5 seconds (VA and VM), and number of participants for each structured activity who have valid accelerometer data are shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants.

| Structured Physical Activities (n=181) | Free-Living Activity (n=42) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) ± SD (range) | 12.0 ± 1.5 (8–15) | 12.6 ± 0.8 (11–14) |

| 8–9 yr olds (n (%)) | 25 (13.8%) | 0 |

| 10–11 yr olds (n (%)) | 54 (29.8%) | 9 (21.4%) |

| 12 yrs and older (n (%)) | 102 (56.4%) | 32 (78.6%) |

| Height (cm) | 152.3 ± 14.5 | 156.5 ± 10.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 52.1 ± 18.2 | 57.1 ± 16.5 |

| Resting VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 2.0 |

| Male (%) | 53.6% | 64.3% |

| BMI Classification | ||

| Normal Weight (5th–85th percentile) | 57.2% | 45.2% |

| Overweight (85th–95th percentile) | 17.8% | 26.2% |

| Obese (≥ 95th percentile) | 25.0% | 28.6% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 33.2% | 21.4% |

| Black/African American | 51.4% | 64.2% |

| Native American/Alaskan | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| Asian | 12.1% | 19.2% |

| White | 35.3% | 16.6% |

Table 2.

Mean (± SD) measured (Cosmed K4b2) oxygen consumption (VO2), child-MET (Measured VO2 for the activity divided by measured resting VO2) and wrist counts per 5 seconds (vertical axis and vector magnitude) from the ActiGraph accelerometer for each structured activity.

| Activity | Measured VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) | Measured child-MET | ActiGraph Wrist (counts per 5 seconds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Vertical Axis | Vector Magnitude | |||

| Supine Rest (n=177) | 4.9 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.0) | 26 (31.2) | 77 (90.2) |

| Watching Television (n=36) | 4.9 (1.4) | 1.1 (0.3) | 21 (26.5) | 61 (54.7) |

| Searching Internet (n=36) | 4.7 (1.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 12 (11.3) | 33 (31.2) |

| Reading (n=38) | 4.9 (1.6) | 1.1 (0.4) | 30 (39.4) | 91 (81.4) |

| Playing Computer Games (n=42) | 6.3 (2.3) | 1.4 (0.5) | 13 (19.0) | 33 (40.1) |

| Playing Board Games/Cards (n=42) | 6.6 (2.1) | 1.4 (0.5) | 138 (83.2) | 356 (188.0) |

| Workout Video (n=35) | 10.1 (3.2) | 2.2 (0.7) | 653 (188.4) | 1193 (318.1) |

| Nintendo Wii (n=38) | 11.4 (5.7) | 2.4 (1.1) | 687 (326.7) | 1061(443.3) |

| Vacuuming (n=37) | 11.6 (3.0) | 2.6 (0.6) | 213 (74.7) | 495 (93.0) |

| Sweeping (n=38) | 13.0 (6.3) | 2.8 (1.1) | 372 (120) | 664 (199.7) |

| Light Cleaning (n=42) | 13.2 (3.5) | 3.0 (1.3) | 315 (133.2) | 595 (283.8) |

| Slow Track Walking (n=38; avg. 74.6 ± 8.6 m·min−1) | 15.1 (3.2) | 3.3 (1.1) | 397 (122.6) | 626 (188.1) |

| Dance Dance Revolution (n=36) | 15.2 (4.2) | 3.3 (1.0) | 255 (141.6) | 412 (204.3) |

| Playing Catch (n=36) | 17.1 (5.2) | 3.7 (1.1) | 889 (304.0) | 1456 (446.6) |

| Walk with 4.5 kg Backpack (n=35; avg. 78.8 ± 13.6 m·min−1) | 17.0 (4.7) | 3.7 (1.2) | 363 (125.8) | 587.6 (183.8) |

| Walking Course (n=60; avg. 71.7 ± 11.8 m·min−1) | 18.4 (4.8) | 4.1 (1.5) | 401 (161.6) | 586 (225.2) |

| Brisk Track Walking (n=37; avg. 93.0 ± 11.3 m·min−1) | 19.6 (3.9) | 4.3 (1.4) | 440 (128.3) | 758 (243.0) |

| Trazer (n=35) | 19.4 (7.5) | 4.4 (1.8) | 561 (223.4) | 917 (319.4) |

| Floor Light Space (n=38) | 21.5 (7.0) | 4.6 (1.8) | 508 (191.8) | 854 (280.5) |

| Soccer Around Cones (n=36) | 21.2 (8.0) | 4.6 (2.1) | 476 (233.8) | 835 (375.0) |

| Jackie Chan (n=42) | 21.7 (5.9) | 4.7 (1.4) | 364 (206.5) | 592 (298.5) |

| Wall Light Space (n=36) | 21.0 (6.1) | 4.5 (1.6) | 863 (269.5) | 1485 (394.8) |

| Wall Ball (n=42) | 22.2 (7.5) | 5.0 (2.3) | 931 (207.7) | 1461 (310.9) |

| Sport Wall (n=37) | 24.2 (8.6) | 5.5 (2.2) | 870 (304.5) | 1412 (399.9) |

| Track Running (n=35; avg. 105.9 ± 17.7 m·min−1) | 24.2 (10.6) | 5.5 (2.5) | 917 (420.8) | 1318 (537.1) |

| Running Course (n=58; avg. 113.1 ± 19.1 m·min−1) | 31.2 (7.7) | 7.0 (2.8) | 1015 (332.0) | 1432 (159.8) |

Development of ActiGraph ROC Wrist Cut-points

The ActiGraph wrist VA (ROC-VA) and VM (ROC-VM) cut-points (counts per 5 seconds), area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity for the ROC curve analysis are shown in table 3. The ROC-VA and ROC-VM SB cut-points, in general, had the highest sensitivity (0.871 and 0.852, respectively), specificity (0.959 and 0.937, respectively), and AUC (0.944 and 0.935, respectively), except for the sensitivity for MPA cut-points which were higher for the ROC-VA (0.888) and ROC-VM (0.916).

Table 3.

Regression analysis and receiver operating curve (ROC) cut-points for sedentary behavior and light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity for the ActiGraph wrist vertical axis and vector magnitude counts per 5 seconds. Sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) are for the ROC analysis. All AUC curves are significant (P<0.001).

| Regression Analysis | ROC Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Cut-point (counts per 5 seconds) | Cut-point (counts per 5 seconds) | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC (Standard Error) | ||

| Vertical Axis | SB | ≤ 35 | ≤ 105 | 0.871 | 0.959 | 0.944 (0.008) |

| LPA | 36 – 360 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| MPA | 361 – 1129 | ≥ 262 | 0.888 | 0.697 | 0.852 (0.011) | |

| VPA | ≥ 1130 | ≥ 565 | 0.756 | 0.773 | 0.840 (0.016) | |

| Vector Magnitude | SB | ≤ 100 | ≤ 275 | 0.852 | 0.937 | 0.935 (0.009) |

| LPA | 101 – 609 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| MPA | 610 – 1809 | ≥ 416 | 0.916 | 0.634 | 0.841 (0.011) | |

| VPA | ≥ 1810 | ≥ 778 | 0.820 | 0.696 | 0.825 (0.017) | |

SB, sedentary behavior (<1.5 METs); LPA, light physical activity (1.5–2.99 METs); MPA, moderate physical activity (3.00–5.99 METs); VPA, vigorous physical activity (≤ 6.00 METs).

Development of ActiGraph Wrist Regression Equations

For the regression equations, inactivity thresholds were developed to distinguish SB from LPA. Based on the examination of the mean values and percentile distribution of the sedentary activities (i.e. activities <1.5 METs) the inactivity threshold for the wrist VA (REG-VA) and VM (REG-VM) were ≤ 35 counts per 5 sec and ≤ 100 counts per 5 seconds, respectively. Thus, when the counts per 5 seconds are below the inactivity threshold the individual is credited with 1.0 child-MET. Shown below are the wrist VA and VM regression models, which consist of two parts (inactivity threshold and a single regression model),

Wrist VA Regression Model (REG-VA):

if the VA (x-axis) countsper 5 sec are ≤ 35, energy expenditure = 1.0 child-MET,

if the VA counts per 5 sec are > 35, energy expenditure (child-MET) = 1.592 + (0.0039* ActiGraph VA counts per 5 s) (R2 = 0.435; SEE = 1.678)

Wrist VM Regression Model (REG-VM):

if the VM countsper 5 sec are ≤ 100, energy expenditure = 1.0 child-MET,

if the VM counts per 5 sec are > 100, energy expenditure (child-MET) = 1.475 + (0.0025* ActiGraph VM counts per 5 s) (R2 = 0.409; SEE = 1.721)

Once a child-MET value was calculated for each 5-sec epoch within a minute on the ActiGraph clock, the average child-MET value of 12 consecutive 5-sec epochs within each minute was calculated to obtain the average child-MET value for that minute. Table 3 shows the cut-points based on the regression models.

Validation Study to Examine the ActiGraph Cut-points and Regression Equations during Unstructured PA

On average, children were monitored for 95.0 ± 36.5 min (range, 25–130 minutes) during the unstructured PA measurement period. Table 4 shows the mean measured and predicted child-MET, mean bias, 95% PI, and RMSE from the unstructured PA measurement. There were no significant differences between the mean measured child-METs and the mean estimates of REG-VA (−3.2% mean bias) or REG-VM (−6.1% mean bias) (P > 0.05). However, there were large individual errors with the 95% prediction intervals ranging from −2.43 to 2.64 child-METs for REG-VA and −2.55 to 2.96 for REG-VM.

Table 4.

Measured (Cosmed K4b2) and predicted child-MET, mean bias (measured minus predicted) and 95% prediction intervals (95%PI), and root mean squared error (RMSE), for the unstructured physical activity measurement.

| Cosmed K4b2 | REG-VA | REG-VM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean child-MET (±SD) | 3.35 (2.13) | 3.25 (1.47) | 3.15 (1.30) |

| Mean bias (95% PI) | --- | 0.11 (−2.43, 2.64) | 0.21 (−2.55, 2.96) |

| RMSE | --- | 1.26 | 1.38 |

Child-MET, metabolic equivalents (measured VO2 divided by measured lying RMR VO2); REG-VA, wrist vertical axis regression model; REG-VM, wrist vertical axis regression model.

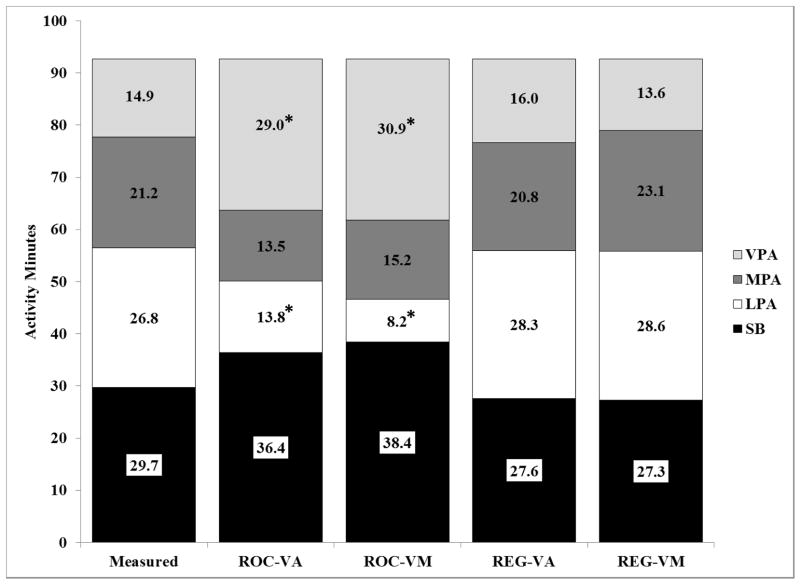

Mean measured and predicted time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA during the unstructured PA measurement are shown in figure 1. Table 5 shows the mean bias and 95% prediction intervals (95%PI) for time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA during the unstructured PA measurement. The REG-VA and REG-VM models were not significantly different from measured time spent in SB, LPA, MPA or VPA (P < 0.05) and had mean biases that ranged from 2.2% to 8.4%. The ROC-VA and ROC-VM models both significantly overestimated measured time in VPA by 94% and 107%, respectively, and significantly underestimated LPA by 47% and 69%, respectively (P<0.05). However, there were no significant differences between measured and estimated time spent in SB (22% to 29% mean bias) or MPA (26% to 38% mean bias) (P>0.05). Both the regression and ROC prediction methods had large individual errors (95% PI range), which were similar across methods.

Figure 1.

Distribution of average time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA) and vigorous physical activity (VPA) during the unstructured PA measurement period for the Cosmed K4b2 (Measured), wrist vertical axis and vector magnitude Receiver Operator Characteristic cut-points (ROC-VA and ROC-VM, respectively), and the wrist vertical axis and vector magnitude regression models (REG-VA and REG-VM, respectively). *Significantly different from measured time (P<0.05).

Table 5.

Mean bias (measured minus predicted) and lower and upper 95% prediction intervals for time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA) and moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during the unstructured PA measurement.

| ROC-VA | ROC-VM | REG-VA | ROC-VM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB | −6.7 (−36.7, 23.3) | −8.6 (−44.0, 23.7) | 2.1 (−29.1, 33.3) | 2.5 (−36.7, 41.6) |

| LPA | 13.0 (−20.1, 46.1) | 18.6 (−19.6, 56.7) | −1.5 (−27.6, 24.7) | −1.9 (−28.5, 24.8) |

| MPA | 7.7 (−35.5, 51.0) | 6.0 (−42.0, 54.1) | 0.5 (−34.5, 35.5) | −1.9 (−40.4, 36.6) |

| VPA | −14.1 (−56.9, 28.7) | −16.0 (−59.4, 27.5) | −1.1 (−37.4, 35.3) | 1.3 (−37.0, 39.6) |

| MVPA | −6.3 (−41.5, 28.8) | −9.9 (−54.9, 35.0) | −0.6 (−33.2, 32.0) | −0.6 (−39.1, 37.8) |

ROC-VA, wrist vertical axis Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) cut-points; ROC-VM, wrist vector magnitude ROC cut-points; REG-VA, wrist vertical axis regression model; REG-VM, wrist vector magnitude regression model.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to develop ActiGraph prediction models for the wrist accelerometer placements in youth using both ROC analyses and regression analyses for the prediction of child-METs, and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. These models were then validated in an unstructured PA setting (simulated free-living). The primary finding is that the wrist REG-VA and REG-VM models have a lower mean bias and were not significantly different from measured values for prediction of child-METs or time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. In contrast, the ROC-VA and ROC-VM models developed using ROC analysis were significantly different from measured time spent in LPA and VPA and had larger mean biases at the group level for all PA intensity categories compared to the regression models. Thus, the regression method appeared to be superior to the ROC curve method for estimating the mean time spent in various intensity categories. However, it should be noted that all models had large individual errors for prediction of child-METs and PA intensity categories.

In recent years, the wrist accelerometer placement site has been studied in adults and children but most of these studies have used devices other than the ActiGraph. For example, Heil et al. (7) performed a laboratory-based study using the Actical accelerometer in children using the hip, wrist (non-dominant), and ankle (same side as wrist accelerometer) locations. Based on the algorithms developed using the accelerometer counts per minute, the study showed that all three sites yielded no significant differences from measured energy expenditure. This was one of the first studies to highlight the potential of the wrist as an alternative placement site for providing valid estimates of PA. Recently, Trost et al. (22) using pattern recognition models, showed that the wrist (non-dominant hand) accelerometer placement site performed as well as the hip accelerometer placement site using the ActiGraph GT3X+, for identification of structured activities; however they did not estimate energy expenditure. Specifically, the classification accuracy for lying, sitting, standing, walking, running, and basketball were ranged from 81.9% to 96.8% for the hip location and 74.6% to 95.8% for the wrist location. Schaefer et al. (18) used ROC analyses to established PA cut-points for the GENEActiv wrist placement (non-dominant wrist). Results of the study using the calibration data identified that both SB and VPA cut-points classified well (83.3% and 88.7%, respectively), however, LPA and MPA cut-points only classified 27.6% and 41.0%, respectively, of the time spent in those categories correctly.

To our knowledge, there is only one other calibration study that developed regression equations to be used with wrist-worn ActiGraph data in youth. Recently, Hildebrand and colleagues (8) used the non-dominant wrist in 30 youth 7–11 years of age, and found a strong correlation (R2=0.71) between measured energy expenditure (eight structured activities) and raw ActiGraph acceleration (mg). They also developed cut-points using the raw acceleration and found high classification accuracy for intensity of SB and LPA (>95%); however intensity classification accuracy was lower for MPA (<50%) and VPA (<80%). In this study, they also placed an ActiGraph on the hip and found a slightly higher correlation with measured energy expenditure (R2=0.78); however, the classification accuracy of activity intensity was similar between the two sites. In addition, they showed that the acceleration values between the wrist and hip locations are different, but when site specific equations are developed, the intensity outcomes are similar.

While the main purpose of the current study was to develop regression models to be used with the ActiGraph accelerometer worn on the dominant wrist; we can also draw some comparisons with previously developed hip models. Recently, our group used the exact same data set that was used in this study, to develop a two regression model for the hip location using the VA and VM (2) and then performed a validation study using the exact same unstructured PA data set used in this study (3). We found that during the unstructured PA validation study, the 2-regression models for the hip underestimated measured values by 0.89–0.91 child-METs and had a RMSE of 1.50–1.55, which were the lowest of the hip models tested (3). In the current study, the wrist location had lower mean biases for predicting child-METs (0.11–0.21 child-METs) and lower RMSE (1.26–1.38), compared to the hip models we developed previously. To draw further comparisons we combined the previously published hip data (VA and VM hip 2-regression models) with the current wrist data (VA and VM wrist regression models). As shown by Hildebrand et al. (8), there were strong correlations between measured and predicted child-METs and time spent in SB and LPA, but the correlations were weak between measured and predicted time spent in MPA and VPA (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows the correlations between the measured and predicted values for child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA during the unstructured PA measurement). When examining differences between the prediction methods for child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA, the hip models were significantly different from the wrist models for child-METs and time spent in LPA and VPA (P<0.05). In addition, the wrist models yielded smaller (non-significant) errors than the waist models. (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows the measured and predicted values for energy expenditure and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA during the unstructured PA measurement). Given that the same data sets were used for development and validation of the hip and wrist models we are able to directly compare how models develop for the wrist compared to those developed for the waist. This is an important and significant finding; it shows that placing the ActiGraph on the dominant wrist is potentially a better location than the hip for estimating child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA.

A second outcome of the study is the comparison of cut-points developed using ROC analysis versus regression analysis. The current study found that the cut-points developed using the regression equations had lower mean biases (2.2 to 8.4%) than those developed using the ROC analysis (22 to 69%), for time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. In addition, the ROC cut-points were significantly different from measured time spent in VPA and MVPA and also provided higher estimates compared to the regression model cut-points of VPA and MVPA, which were not significantly different from measured values. The choice of which cut-points to use has implications for PA researchers looking to quantify MVPA or estimate the prevalence of those meeting the PA recommendation. Our study is in agreement with Schaefer et al. (17) who used ROC and regression analyses to establish PA cut-points for the wrist using the Actical accelerometer. They then used a free-living sample to estimate the minutes of MPA and VPA and percent of participants meeting the PA recommendation of 60 minutes per day using both methods. They found that the cut-points developed using ROC analysis gave higher values, compared to the linear regression model for time spent in MPA (116.6 vs 71.4 min, respectively) and VPA (24.1 vs 11.8 min, respectively) and the percent of individuals meeting the PA recommendation (97.8% vs 75.8%, respectively). However, a limitation of this study was that they did not have a gold standard for actual time spent in intensity categories, so it is unclear from the study of Schaefer et al. (17), which values were correct. Based on the results of the current study, and those of Schaefer et al. (17) it is recommended that ROC analyses not be used for the development of cut-points as they appear to increase the prediction error.

The current study used the wrist location for predicting child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA of youth, using the ActiGraph accelerometer. As previously mentioned, the 2008–2011 NHANES changed their protocol to use the (non-dominant) wrist location instead of the hip location. This change will allow for improved wear time compliance and also the ability to track sleep variables. However, one complicating issue is that previous studies in adults and children have not consistently used the dominant or non-dominant wrist location. Esliger et al. (5) showed that both the right and left wrists could be used to predict PA intensity and the accelerometer output had similar correlations with measured energy expenditure (left wrist, r = 0.86 and right wrist, r = 0.83). Conversion of accelerometer output from the non-dominant to dominant wrist location, however, is probably impossible due to differences in how activities are performed between the dominant and non-dominant hands. Future work needs to compare the difference between the dominant and non-dominant wrists for prediction accuracy of energy expenditure and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. At this time, it is unclear which wrist location should be used, although we found promising results with the dominant wrist.

This study has several strengths. A large sample of youth was included in both the development and the unstructured PA validation, and both settings used indirect calorimetry as a criterion measure of energy expenditure. The study sample also had a wide range of ages, BMI levels, and racial and ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, the models developed are easily applied to existing data sets. Limitations of the study include limited vigorous intensity PA used to develop the models, and a restriction of unstructured PA activities due to being constrained to the college campus or school campus. Lastly, due to our use of the dominant wrist, the models developed here cannot be directly applied to the NHANES data; however other researchers using the dominant wrist can apply these methods.

In conclusion, this study highlights the use of an ActiGraph accelerometer worn on the dominant wrist. Compared to measured values, the VA and VM regression models, developed on the wrist accelerometer data, had insignificant mean bias for child-METs and times spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA. In addition, the regression models appeared to be superior to the ROC cut-points developed for activity intensity classification. Lastly, the use of the wrist regression equations resulted in lower mean biases and RMSEs for estimates of child-METs and time spent in SB, LPA, MPA, and VPA, compared to previously developed hip models using the same structured activities and unstructured PA measurement methods. Future work is needed to investigate differences between the dominant and non-dominant wrist locations, and to explore pattern recognition models.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. .docx Table, Pearson correlation coefficients between measured (Cosmed) and ActiGraph hip (Crouter vertical axis (VA) 2-regression model and Crouter vector magnitude (VM) 2-regression model) and wrist (VA single regression model and VM single regression model) prediction methods for child-METs and time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA) and moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA) during approximately two hours of unstructured PA. All correlations are significant (P ≤ 0.001).

Supplemental Digital Content 2. .docx Table, Measured (Cosmed) and predicted (ActiGraph hip: Crouter vertical axis (VA) 2-regression model and Crouter vector magnitude (VM) 2-regression model; ActiGraph wrist: VA single regression model and VM single regression model) child-METs and time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA) and moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA) during approximately two hours of unstructured PA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIH grant no. NIH R21HL093407. No financial support was received from any of the activity monitor manufacturers, importers, or retailers. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

The authors would like to thank the research participants and Magdalene Horton, Prince Owusu, Larry Kennard, Katie Dooley, Shawn Pedicini, Rachel Mclellan, and Sarah Sullivan for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This research was supported by NIH Grant 5R21HL093407. There are no declared conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) About BMI for Children and Teens. 2011 [cited 2011 February 1]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- 2.Crouter SE, Horton M, Bassett DR., Jr Use of a Two-Regression Model for Estimating Energy Expenditure in Children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(6):1177–85. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182447825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crouter SE, Horton M, Bassett DR., Jr Validity of ActiGraph Child-Specific Equations during Various Physical Activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(7):1403–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318285f03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekblom O, Nyberg G, Bak EE, Ekelund U, Marcus C. Validity and comparability of a wrist-worn accelerometer in children. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(3):389–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esliger DW, Rowlands AV, Hurst TL, Catt M, Murray P, Eston RG. Validation of the GENEA Accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(6):1085–93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820513be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(14):1557–65. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heil DP. Predicting activity energy expenditure using the Actical activity monitor. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77(1):64–80. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hildebrand M, Van Hees VT, Hansen BH, Ekelund U. Age-Group Comparability of Raw Accelerometer Output from Wrist- and Hip-Worn Monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(9):1816–24. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson E, Ekelund U, Nero H, Marcus C, Hagstromer M. Calibration and cross-validation of a wrist-worn Actigraph in young preschoolers. Pediatr Obes. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00213.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumahara H, Tanaka H, Schutz Y. Daily physical activity assessment: what is the importance of upper limb movements vs whole body movements? Int J Obes (Lond) 2004;28(9):1105–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malina RM, Bouchard C, Bar-Or O. Growth, Maturation, and Physical Activity. 2. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 2004. p. 728. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannini A, Intille SS, Rosenberger M, Sabatini AM, Haskell W. Activity recognition using a single accelerometer placed at the wrist or ankle. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(11):2193–203. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829736d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melanson EL, Jr, Freedson PS. Validity of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. (CSA) activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):934–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pate RR, Almeida MJ, McIver KL, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M. Validation and calibration of an accelerometer in preschool children. Obesity. 2006;14(11):2000–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberger ME, Haskell WL, Albinali F, Mota S, Nawyn J, Intille S. Estimating activity and sedentary behavior from an accelerometer on the hip or wrist. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(5):964–75. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827f0d9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruch N, Rumo M, Mader U. Recognition of activities in children by two uniaxial accelerometers in free-living conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(8):1917–27. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer CA, Nace H, Browning R. Establishing wrist-based cutpoints for the actical accelerometer in elementary school-aged children. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(3):604–13. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2011-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaefer CA, Nigg CR, Hill JO, Brink LA, Browning RC. Establishing and Evaluating Wrist Cutpoints for the GENEActiv Accelerometer in Youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(4):826–33. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39 (Suppl 1):5–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Bassett DR, Jr, O’Brien WL, King GA, Ainsworth BE. Estimation of energy expenditure using CSA accelerometers at hip and wrist sites. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S450–6. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trost S, Zheng Y, Wong WK, editors. Machine Learning for Activity Recognition: Hip versus Wrist Data [abstract]; 3rd International Conference on ambulatory Monitoring of Physical Activity and Movement; 2013 June 17–19; Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Amherst; [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. .docx Table, Pearson correlation coefficients between measured (Cosmed) and ActiGraph hip (Crouter vertical axis (VA) 2-regression model and Crouter vector magnitude (VM) 2-regression model) and wrist (VA single regression model and VM single regression model) prediction methods for child-METs and time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA) and moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA) during approximately two hours of unstructured PA. All correlations are significant (P ≤ 0.001).

Supplemental Digital Content 2. .docx Table, Measured (Cosmed) and predicted (ActiGraph hip: Crouter vertical axis (VA) 2-regression model and Crouter vector magnitude (VM) 2-regression model; ActiGraph wrist: VA single regression model and VM single regression model) child-METs and time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA) and moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA) during approximately two hours of unstructured PA.