Abstract

Background

Studies in integrated health systems suggest that patients often accumulate oversupplies of prescribed medications, which is associated with higher costs and hospitalization risk. However, predictors of oversupply are poorly understood, with no studies in Medicare Part D.

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe prevalence and predictors of oversupply of antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and antihyperlipidemic medications in adults with diabetes managed by a large, multidisciplinary, academic physician group and enrolled in Medicare Part D or a local private health plan.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study. Electronic health record data were linked to medical and pharmacy claims and enrollment data from Medicare and a local private payer for 2006-2008 to construct a patient-quarter dataset for patients managed by the physician group. Patients’ quarterly refill adherence was calculated using ReComp, a continuous, multiple-interval measure of medication acquisition (CMA), and categorized as <0.80 = Undersupply, 0.80-1.20 = Appropriate Supply, >1.20 = Oversupply. We examined associations of baseline and time-varying predisposing, enabling, and medical need factors to quarterly supply using multinomial logistic regression.

Results

The sample included 2,519 adults with diabetes. Relative to patients with private insurance, higher odds of oversupply were observed in patients aged <65 in Medicare (OR=3.36, 95% CI=1.61-6.99), patients 65+ in Medicare (OR=2.51, 95% CI=1.37-4.60), patients <65 in Medicare/Medicaid (OR=4.55, 95% CI=2.33-8.92), and patients 65+ in Medicare/Medicaid (OR=5.73, 95% CI=2.89-11.33). Other factors associated with higher odds of oversupply included any 90-day refills during the quarter, psychotic disorder diagnosis, and moderate versus tight glycemic control.

Conclusions

Oversupply was less prevalent than in previous studies of integrated systems, but Medicare Part D enrollees had greater odds of oversupply than privately insured individuals. Future research should examine utilization management practices of Part D versus private health plans that may affect oversupply.

Keywords: Refill adherence, oversupply, medication surplus, diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes affects over 250 million Americans, including 27% of adults age 65 or older, and represents almost $100 billion in annual health care costs.1 A central challenge in achieving optimal disease management in diabetes is appropriate medication use. Most patients require therapy for control of blood sugar, blood pressure (BP), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and/or triglycerides.2 Often, more than one agent must be used to achieve or maintain control.3,4 Complex, multiple-drug regimens are more difficult to follow5 and come with increased risk of adverse drug events,6 particularly for older adults or those with conditions that impair self-management (e.g., dementia).7,8

Underuse of medications is common,9 but non-adherence can take other forms, including overuse of medications.10,11 To maintain adherence to prescribed regimens, patients must acquire appropriate medication supplies by refilling their prescriptions on time. As such, patients’ refill adherence is often used as an indicator of their overall adherence to diabetes regimens. Indeed, there is substantial evidence from pharmacy refill adherence studies that failing to refill prescriptions on time (i.e., having an “undersupply” of medications) in diabetes is associated with missed doses, poorer disease control, hospitalization, and greater health care costs.12,13 However, these studies – as well as existing interventions to support medication adherence – have largely failed to consider potential risks at the other end of the spectrum: when patients accumulate oversupplies of medications. Having large quantities of unneeded medications on hand—e.g., multiple bottles containing the same medication, or large stockpiles of discontinued medications—may make already complex regimens more difficult to follow. When extra medications are on hand, patients may be confused about which medications they are supposed to take and ingest medications that they were instructed to discontinue, either in addition to or in place of medications they should be taking. In turn, this may lead patients to experience adverse events. Two studies in older patients and those with heart failure found that patients with ≥120% of their needed annual medication supplies were more likely to be hospitalized.14,15 Accumulating oversupplies of medications also represents wasted health care resources and has been associated with increased health care costs in multiple studies.14-17

Previous oversupply studies were largely conducted outside of the U.S. or in health systems at which payers, providers, and pharmacies are inter-connected through a single electronic health record (EHR), such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). They suggest that oversupply may be common, occurring with antidiabetic medications in up to 53% of patients,16,18-21 with antihypertensive medications in 18-52%,14-16,21-23 and with statins in 27-35%.16,21 However, the magnitude of oversupply in diabetes patients with commercial or public insurance (including Medicare Part D) who are managed in a typical U.S. practice is unknown. Moreover, reasons for oversupplies are poorly understood. This study examined the prevalence of and risk factors for oversupply of medications used ubiquitously by adult diabetes patients (antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive medications) with commercial or Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits and managed in a large, academic, multidisciplinary health system.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pittsburgh and University of Wisconsin approved this study with a waiver of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization.

Study Setting

The patients in this study are associated with a large, Midwestern, academic, multispecialty provider group. This group delivers ~1.7 million ambulatory patient visits per year, and is both a major source of primary care for the local area and a statewide specialty care referral center.

Data Sources

The data for this study included 2006-2008 Medicare fee-for-service medical claims (Parts A and B), enrollment data, and Part D prescription drug event data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), medical/pharmacy claims and enrollment data from a local non-Medicare private payer, and clinical data from the provider group's EHR systems. Enrollment files provided information on demographics, monthly plan enrollment status, date of death, and third party payers. Medical claims provided information on services and procedures performed, and included diagnosis codes, procedure codes, physician identifiers, and date, place, and type of service. Prescription drug files included, for all prescriptions filled by the beneficiary and billed to the payer, the date of service, encrypted prescriber and pharmacy IDs, brand and generic drug name, national drug code (NDC), quantity, and days’ supply dispensed. Claims and enrollment data were linked to the EHR via the patient's Health Insurance Claims (HIC) number (for Medicare beneficiaries) or social security number (for private plan beneficiaries) using a crosswalk from the provider group.

Sample and Design

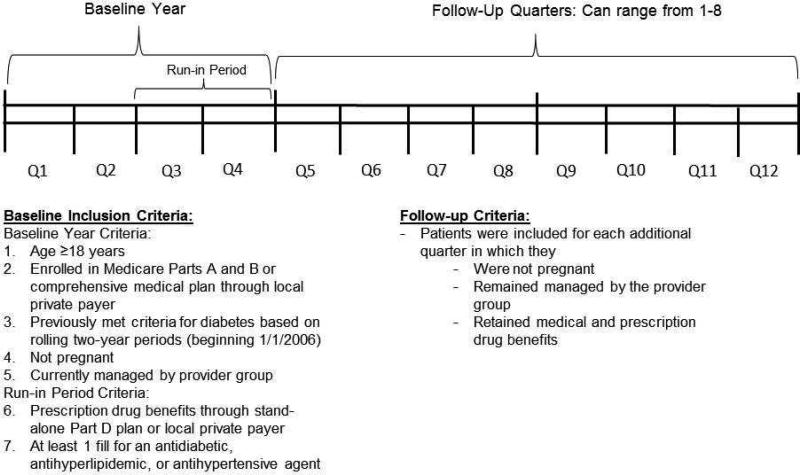

A patient-quarter dataset was constructed for a retrospective cohort of adults with diabetes who were followed longitudinally by the provider group as well as Medicare fee-for-service and/or the local private plan. Patients enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan were excluded due to lack of availability of complete medical claims from CMS for this population. To enter the sample, patients had to meet baseline inclusion criteria over four consecutive quarters during 2006-2008, as well as follow-up criteria for at least one additional consecutive quarter during this time frame (see Figure 1). Baseline inclusion criteria consisted of 1) age ≥18 years, 2) enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B or a comprehensive medical plan through the local private payer, 3) having previously met criteria for having diabetes, 4) not being pregnant, and 5) being currently managed by the provider group (to ensure adequacy of EHR data). In addition, during the latter two quarters of the baseline period (i.e., the “run-in period”), patients were required to 6) have prescription drug benefits through a stand-alone Part D prescription drug plan (PDP) or the local private payer and 7) at least one prescription fill for an antidiabetic, anithyperlipidemic, or antihypertensive agent. Follow-up quarter inclusion criteria were identical to baseline criteria, except that patients were not required to continue to have prescription fills for antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, or antihypertensive agents in follow-up quarters (because follow-up refill behavior was the outcome of interest). Patients continued contributing quarters to the dataset until they failed to meet criteria, death, or December 31, 2008. Thus, patients were followed anywhere from five quarters (baseline four quarters plus one follow-up quarter) to 12 quarters (baseline four quarters plus eight follow-up quarters).

FIGURE 1.

Study design and construction of the study sample.

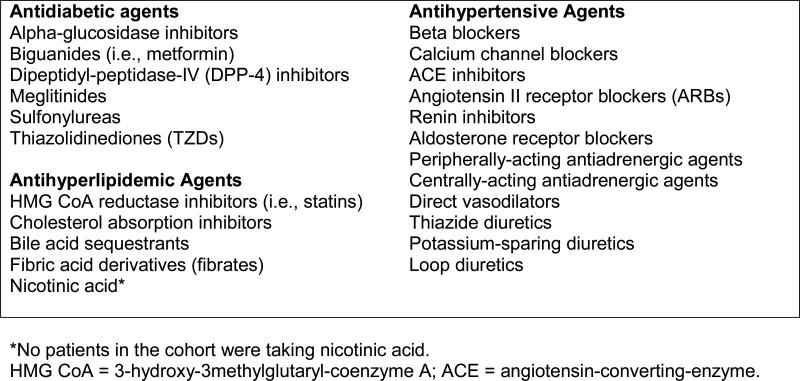

Age, date of death, and medical and pharmacy benefits were determined using payer enrollment files. Patients with diabetes were identified using a validated algorithm24 requiring at least one inpatient or skilled nursing facility (SNF) claim or more than one professional services claim associated with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 250.xx, 357.2, 362.0x, 366.41, or 648.0x in a two-year period. Patients’ meeting of diabetes criteria was assessed on a rolling basis beginning 1/1/2006 and patients were assumed to have diabetes going forward from the date of the first claim identified using this algorithm. Because lifetime claims data were not available for patients, it is possible that some patients had earlier claims for diabetes, and thus, it was not possible to distinguish between incident versus prevalent diabetes cases. Two established approaches using patients’ face-to-face outpatient evaluation and management (E&M) visits were applied to determine whether patients were managed by the provider group: 1) the “plurality provider algorithm,”25,26 which assigns patients to the group accounting for the greatest number of E&M visits in a given year; and 2) the “Diabetes Care Home” method, which considers a patient with diabetes to be managed by a provider group in a given year if they had ≥2 E&M visits to a primary care provider (PCP), or one visit to a PCP and one visit to an endocrinologist, over the current and prior year.27 Patients were included if they met either or both of these criteria. To determine use of antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents, patients’ prescription records were linked to the Multum Lexicon™ Plus database (Cerner Multum, Inc., Denver, CO) via the National Drug Code (NDC) associated with each prescription record. Patients who had at least one fill associated with an NDC classified by Lexicon Plus in the therapeutic subclasses shown in Figure 2 during the run-in period were included in this study. Insulin and other injectable antidiabetic medications (amylin analogs, incretin mimetics) were not included due to difficulties in accurately capturing days’ supply dispensed of insulin using claims data13 and the very infrequent use (<0.5% of all antidiabetic refill records) of the newer non-insulin injectibles at the time of this study. Finally, pregnancy was determined by prenatal and postnatal diagnosis and procedure codes.28

FIGURE 2.

Subclasses of antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents included in the study.

Measures

Dependent variable: quarterly medication supply

To calculate patients’ quarterly supply of antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents, the validated ReComp algorithm29 was applied to patients’ pharmacy claims over the run-in period and all follow-up quarters. A detailed description of how ReComp is calculated has previously been published. 29 Briefly, ReComp is a continuous, multiple-interval measure of medication acquisition (CMA), representing the number of days’ supply of medications available to the patient over the number of days in an interval.29 ReComp values can be as low as 0 (no medications available) and have no theoretical upper limit. Values <1 represent fewer days’ supply than days in the interval; values >1 represent more days’ supply than interval days; values of 1 indicate an exact match between days’ supply and interval days. ReComp has demonstrated clinical validity,29 and has been used in past studies of oversupply,22 and is ideal for examining oversupply. That is, oversupplies due to overlapping prescriptions obtained later in an observation period cannot compensate for a prior undersupply, and oversupplies existing at the end of an observation period are carried forward into the subsequent observation period. Finally, ReComp was developed specifically to characterize changes in medication supplies in successive, short (e.g., 30-day or 90-day) time intervals, allowing for the capture of more detail regarding fluctuations in medication supply over time and an examination of these fluctuations in relation to other time-varying factors.

The Lexicon™ Plus database was used to group medications into the therapeutic subclasses shown in Figure 2. Then, for each subclass that was filled by a patient during the run-in period, ReComp was calculated in quarterly (90-day) increments for all qualifying patient-quarters. Subclasses were chosen as the appropriate unit for which to calculate ReComp instead of broad drug class (e.g., antidiabetics, antihypertensives) because patients are often simultaneously prescribed more than one subclass (e.g., metformin plus sulfonylurea; beta blocker and ACE inhibitor).30 The mean of these subclass-specific values was computed for each quarter to generate one summary measure of medication supply for each patient-quarter and then categorized as undersupply (ReComp<0.80), appropriate supply (ReComp=0.80-1.20), or oversupply (ReComp>1.20).16 Three separate average ReComp values were also calculated and categorized for each broad class (antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents) for use in sensitivity analyses (described below).

Independent variables: time invariant

The Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization,31 which has often been applied to medication use behaviors,32 along with other predominant conceptual models of medication adherence33,34 and prior research on oversupply were used to guide the selection of independent variables for this study.14-16,22 Predisposing factors: The payer enrollment files were used to determine patient sex and race/ethnicity (Black, White, or Other/Unknown). Enabling factors: It was not possible to investigate the effect of insurance status independent of age given very few privately insured individuals age 65 or older. Thus, patients were categorized into five mutually exclusive age-insurance groups: 1) any age and privately insured, 2) <65 years and enrolled in Medicare only, 3) <65 years and enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, 4) ≥65 years and enrolled in Medicare only, 5) ≥65 and enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. Care continuity was measured using Ejlertsson's K-Index,35 which measures the extent to which each patient's outpatient visits were concentrated among few versus more providers; higher scores represent more continuous care. Medical need factors: Several measures of each patient's need for medications were generated using data from the baseline four quarters. Predicted future healthcare utilization was captured using all diagnoses recorded in professional services/carrier and inpatient/outpatient facility claims to calculate the Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System's (v9.0) ACG-Predictive Model (ACG-PM). Several indicators for specific cognitive and mental health conditions were created using established ICD-9 diagnosis code algorithms applied to medical claims, including dementia,36 depression,37 alcohol or drug abuse,37 and psychosis.37 Elixhauser ICD-9 diagnosis code criteria37 were applied to create an indicator for having any diabetes complications (identified using codes 250.40-250.93 or 249.40-249.91, which include renal, ophthalmic, and neurological complications, peripheral circulatory disorders, and other specified or unspecified complications). In addition, whether or not the patient had any fills for insulin during his/her run-in period was used as an indicator of greater diabetes severity. Finally, as medication regimen complexity has previously been shown to predict patients’ refilling behavior, data from patients’ run-in period quarters were used to calculate diabetes-related regimen complexity as well as overall medication regimen complexity. Specifically, the total number of diabetes-related (antidiabetes, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive) medication subclasses used during the run-in period (categorized as 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, or ≥7) was used as an indicator of diabetes-specific regimen complexity, while the total number of all unique drug products used in the run-in period (categorized as 0-5, 6-10, 11-15, or ≥16) was used to characterize the complexity of their overall medication regimen.

Independent variables: time variant

Several time-variant (quarterly) enabling and medical need variables were created. Enabling factors included the total number of providers seen for outpatient E&M visits25 within a quarter (categorized as 0, 1, 2, or ≥3), as well as whether or not the patient obtained any 90-day fills for diabetes-related medications during the quarter, both which may facilitate patients’ acquisition of duplicative or surplus medications. Time-varying medical need factors included having an inpatient stay during the quarter (during which medications can be changed, leading to under- or over-supplies), as well as measures of disease control. Specifically, for each quarter, the most recent HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and blood pressure values prior to the start of the quarter were extracted. These values were then categorized as follows: HbA1c as <7%, 7-<9%, ≥9%, or not tested, LDL as <100 mm/DL, 100-<130 mm/DL, ≥130 mm/DL, or not tested, and blood pressure as <130/80 mmHg, ≥130/80 mmHg, or not tested, based on diabetes treatment guidelines.38

Analytic Approach

Primary analyses

Analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation for continuous variables) were calculated for all independent variables. To describe the primary outcome of interest (oversupply), the percent of patients with any oversupply over their study quarters, as well as the total number and percent of quarters in which patients had oversupply, were calculated. Multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate the association of predisposing, enabling, and medical need factors to oversupply or undersupply of medications in a given quarter, with appropriate supply as the reference category and all independent variables entered simultaneously. Consistent with prior research,22,39 multinomial logistic regression was deemed the optimal modeling approach to accommodate the three-category nature of the dependent variable (oversupply, appropriate supply, and undersupply), while not imposing the restriction that the predictors of having oversupply versus appropriate supply are identical to the predictors of having undersupply versus appropriate supply.

Robust estimates of the variance were used to account for clustering within patients over time..40 Adjusted predicted probabilities were then estimated using the recycled predictions approach using Stata's “margins” command. The delta method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals, allowing for correlation among observations.

Sensitivity analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted. To address the potential for confounding by disease severity, the regression model was re-estimated stratifying by 1) whether or not patients had complicated versus uncomplicated diabetes, and 2) whether their ACG-Risk Score fell above or below the median split. To address the possibility that refill adherence may be incorrectly calculated for quarters in which a hospitalization occurs and this may affect adherence values for quarters following a hospitalization, the regression model was also re-estimated after eliminating all quarters in which patients resided in a hospital or skilled nursing facility and all subsequent quarters for these patients. Because results were substantively similar (available on request), only primary model results are presented. The final sensitivity analysis addressed the fact that using ReComp values averaged across all three classes of medications (antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents) may obfuscate variation in ReComp values across classes. Thus, the regression was re-run using the alternative ReComp variables calculated separately for each of the three broad classes of diabetes-related medications (antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents); results are reported in Appendices 1a-1c. Subclass-level analyses were not feasible due to reduced numbers of patients who were taking each individual subclass.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 2,519 patients contributing 12,995 quarters of follow-up. Just over half of patients were female, and 88% were white (Table 1). A majority had Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits, with 38% age ≥65 in Medicare only, 9% age ≥65 in both Medicare and Medicaid, 7% age <65 in Medicare only, and 14% age <65 in both Medicare and Medicaid. The remaining 32% of patients were privately insured. Approximately 21% of patients at baseline had diabetes complications, 14% had depression, and 6% had dementia. A majority (74%) of patients took at least 3 diabetes-related medications at baseline, and 72% took at least 6 or more total medications. Insulin was used by 27% of patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2,519 adults with diabetes using antidiabetic, anti-hyperlipidemic, and/or antihypertensive medications and followed for 12,995 quarters.

| Time-Invariant Measures | |

|---|---|

| Female, %(n) | 51.4% (1,294) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, %(n) | 87.6% (2,207) |

| Black, %(n) | 6.9% (173) |

| Other/Unknown, %(n) | 5.5% (139) |

| Age and Insurance Status | |

| HMOa coverage only (any age) | 31.8% (800) |

| Age <65 in Medicare only | 7.1% (179) |

| Age <65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 13.9% (349) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare only | 37.9% (955) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 9.4% (236) |

| Baseline ACG-PMb score, M(SD) | 1.5 (1.2) |

| Chronic Conditions at Baseline | |

| Diabetes complications, %(n) | 20.7% (521) |

| Depression, %(n) | 14.1% (355) |

| Dementia, %(n) | 5.5% (139) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse, %(n) | 3.2% (80) |

| Psychoses, %(n) | 10.6% (267) |

| Total number of diabetes-related medicationsc at baseline | |

| 1-2 | 26.1% (657) |

| 3-4 | 38.9% (979) |

| 5-6 | 26.2% (660) |

| ≥7 | 8.9% (223) |

| Total number of unique medications (all types) at baseline | |

| 0-5 | 28.7% (722) |

| 6-10 | 40.6% (1,022) |

| 11-15 | 20.6% (518) |

| ≥16 | 10.2% (257) |

| K-index for study period, M(SD) | 0.7 (0.2) |

| Insulin use, %(n) | 26.5% (668) |

| Time-Varying Measures | |

|---|---|

| Number of unique providers seen for E&Md visits per quarter | |

| 0 | 21.2% (2,754) |

| 1 | 35.8% (4,650) |

| 2 | 22.1% (2,875) |

| ≥3 | 20.9% (2,716) |

| Any days in inpatient setting | 9.4% (1,221) |

| Any 90-day prescription fills in the quarter | 13.1% |

| (1,705) | |

| Last available A1ce prior to quarter | |

| <7% | 47.4% (6,156) |

| 7% to <9% | 37.0% (4,811) |

| ≥9% | 10.3% (1,333) |

| Not tested | 5.4% (695) |

| Last available LDLf prior to quarter | |

| <100 mg/dl | 53.7% (6,984) |

| 100-129 mg/dl | 19.6% (2,541) |

| ≥130 mg/dl | 9.4% (1,224) |

| Not tested | 17.3% (2,246) |

| Last available BPg prior to quarter | |

| Controlled (<130/80) | 71.5% (6,153) |

| Uncontrolled (≥130/80) | 19.2% (5,622) |

| Not Tested | 9.4% (1,220) |

HMO = health maintenance organization

ACG-PM = adjusted clinical groups – predictive model

Includes unique antidiabetes, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive subclasses

E&M = evaluation and management

A1c = glycated hemoglobin

LDL = low-density lipoprotein

BP = blood pressure; mg/dl = milligrams per deciliter.

Over the study period, approximately 10% of patients had at least one quarter in which their average ReComp measures indicated an oversupply (Table 2). Over half (55%) of quarters represented appropriate supply of medications, while 40% of quarters represented undersupply, and 5.5% of quarters represented oversupply. When calculating ReComp separately for antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents, rates of oversupply at the patient and quarter levels were slightly higher, ranging from 5.6% for antihyperlipidemic agents to 7.4% for antihypertensive agents.

Table 2.

Patient-level and quarter-level measures of medication supply for diabetes-related agents, for all medications combined and individual medication categories.

| Average Supply Across All Classes | Anti-diabetics Only | Antihyper-lipidemics Only | Antihyper-tensives Only | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least one quarter of oversupply, %(n/N) | 9.9% (250/2,519) | 12.8% (208/1,623) | 11.4% (192/1,679) | 13.0% (281/2,162) |

| Medication Supply in Follow-up Quarters | ||||

| Total number of quarters | 12,995 | 8,489 | 8,770 | 11,871 |

| Oversupply, %(n) | 5.5% (720) | 6.7% (570) | 5.6% (490) | 7.4% (827) |

| Appropriate supply, %(n) | 54.8% (7,126) | 58.1% (4,931) | 61.4% (5,380) | 58.1% (6,491) |

| Undersupply, %(n) | 39.6% (5,149) | 35.2% (2,988) | 331.% (2,900) | 34.6% (3,863) |

Predictors of Medication Oversupply

Table 3 shows odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjusted predicted probabilities from the multinomial logistic regression model for predictors of quarterly oversupply versus appropriate supply. Age/insurance status was significantly and strongly associated with having oversupply rather than appropriate supply across each medication class. Relative to privately insured individuals, the odds of having oversupply versus appropriate supply were higher in patients aged <65 in Medicare (OR=3.36, 95% CI=1.61-6.99), patients <65 in Medicare/Medicaid (OR=4.55, 95% CI=2.33-8.92), patients 65+ in Medicare (OR=2.51, 95% CI=1.37-4.60), and patients 65+ in Medicare/Medicaid (OR=5.73, 95% CI=2.89-11.33). Additionally, having received at least one 90-day fill for study medications in the quarter was also associated with higher odds of oversupply versus appropriate supply compared to patients with no 90-day prescription fills in the quarter (OR = 2.64 [95% CI=1.88-3.70]). Also, diagnosis with a psychotic disorder (OR=1.73 [95% CI=1.05-2.84]) and having moderate versus tight glycemic control (OR=1.38 [95% CI=1.03-1.87]) were associated with increased odds of oversupply versus appropriate supply. No other factors emerged as significant independent predictors of oversupply of diabetes-related medications.

Table 3.

Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Quarterly Undersupply and Oversupply of Diabetes-related Medications

| Odds Ratios (95% CIa) | Adjusted Predicted Probabilities (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undersupply | Oversupply | Undersupply | Appropriate Supply | Oversupply | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (ref) | -- | -- | 0.38 (0.35-0.40) | 0.56 (0.53-0.58) | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) |

| Female | 1.15 (0.99-1.33) | 0.78 (0.55-1.09) | 0.41 (0.39-0.44) | 0.54 (0.52-0.56) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White (ref) | -- | -- | 0.38 (0.36-0.39) | 0.57 (0.55-0.58) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| Black | 1.98 (1.43-2.72)** | 0.86 (0.39-1.88) | 0.53 (0.46-0.60) | 0.43 (0.36-0.50) | 0.04 (0.01-0.06) |

| Other/Unknown | 2.29 (1.64-3.19)** | 1.43 (0.65-3.13) | 0.55 (0.48-0.62) | 0.39 (0.32-0.46) | 0.06 (0.02-0.09) |

| Age and Insurance Status | |||||

| HMO coverage only, any age (ref) | -- | -- | 0.42 (0.39-0.46) | 0.55 (0.52-0.59) | 0.02 (0.01-0.03) |

| Age <65 in Medicare only | 0.87 (0.64-1.18) | 3.36 (1.61-6.99)** | 0.38 (0.32-0.43) | 0.55 (0.50-0.61) | 0.07 (0.04-0.10) |

| Age <65 in Medicare & Medicaid | 1.01 (0.77-1.33) | 4.55 (2.33-8.92)** | 0.40 (0.35-0.45) | 0.51 (0.46-0.56) | 0.09 (0.05-0.12) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare only | 0.89 (0.73-1.09) | 2.51 (1.37-4.60)** | 0.39 (0.36-0.42) | 0.56 (0.53-0.59) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare & Medicaid | 0.80 (0.59-1.08) | 5.73 (2.89-11.33)** | 0.35 (0.29-0.40) | 0.54 (0.49-0.59) | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) |

| Baseline ACG-PMb score | |||||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.35 (0.32-0.38) | 0.59 (0.56-0.62) | 0.06 (0.04-0.08) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.08 (0.92-1.27) | 1.04 (0.72-1.51) | 0.37 (0.34-0.39) | 0.57 (0.55-0.60) | 0.06 (0.04-0.07) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.24 (1.03-1.49)* | 1.09 (0.69-1.71) | 0.39 (0.37-0.42) | 0.55 (0.52-0.58) | 0.06 (0.04-0.07) |

| Quartile 4 | 1.78 (1.42-2.22)** | 1.08 (0.64-1.82) | 0.48 (0.44-0.51) | 0.47 (0.44-0.51) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| Diabetes Complications | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.40 (0.38-0.42) | 0.54 (0.52-0.56) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.74-1.11) | 0.85 (0.55-1.32) | 0.38 (0.34-0.42) | 0.57 (0.53-0.60) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| Depression | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.39 (0.38-0.41) | 0.55 (0.53-0.57) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| Yes | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | 0.82 (0.49-1.37) | 0.41 (0.36-0.45) | 0.55 (0.50-0.59) | 0.05 (0.03-0.07) |

| Dementia | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.40 (0.38-0.41) | 0.55 (0.53-0.57) | 0.05 (0.05-0.06) |

| Yes | 1.08 (0.77-1.52) | 1.54 (0.85-2.77) | 0.40 (0.33-0.47) | 0.52 (0.45-0.59) | 0.08 (0.04-0.11) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.39 (0.38-0.41) | 0.55 (0.53-0.57) | 0.06 (0.05-0.06) |

| Yes | 1.61 (1.05-2.48)* | 0.66 (0.20-2.13) | 0.51 (0.41-0.60) | 0.46 (0.37-0.56) | 0.03 (0.00-0.07) |

| Psychoses | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.41 (0.39-0.42) | 0.54 (0.53-0.56) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| Yes | 0.73 (0.55-0.96)* | 1.73 (1.05-2.84)* | 0.33 (0.28-0.38) | 0.58 (0.53-0.64) | 0.09 (0.06-0.12) |

| Total number of diabetes-related medications at baseline | |||||

| 1-2 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.44 (0.41-0.48) | 0.51 (0.47-0.54) | 0.05 (0.03-0.07) |

| 3-4 | 0.76 (0.62-0.92)** | 0.96 (0.78-1.98) | 0.38 (0.36-0.41) | 0.56 (0.54-0.59) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| 5-6 | 0.71 (0.56-0.89)** | 1.29 (0.75-2.23) | 0.36 (0.33-0.39) | 0.57 (0.53-0.60) | 0.07 (0.05-0.09) |

| ≥7 | 0.85 (0.62-1.16) | 0.54 (0.23-1.16) | 0.42 (0.36-0.47) | 0.55 (0.50-0.61) | 0.03 (0.01-0.05) |

| Total number of unique medications (all types) at baseline | |||||

| 0-5 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.38 (0.35-0.42) | 0.57 (0.54-0.61) | 0.05 (0.03-0.07) |

| 6-10 | 1.08 (0.88-1.32) | 1.24 (0.78-1.98) | 0.40 (0.37-0.42) | 0.55 (0.52-0.58) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| 11-15 | 1.16 (0.90-1.50) | 1.36 (0.76-2.44) | 0.41 (0.37-0.45) | 0.53 (0.50-0.57) | 0.06 (0.04-0.08) |

| ≥16 | 1.20 (0.84-1.71) | 1.90 (0.97-3.71) | 0.41 (0.35-0.47) | 0.51 (0.46-0.57) | 0.08 (0.05-0.11) |

| K-index for study period | |||||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.42 (0.38-0.45) | 0.54 (0.51-0.57) | 0.05 (0.03-0.06) |

| Quartile 2 | 0.94 (0.76-1.15) | 1.51 (0.96-2.37) | 0.39 (0.36-0.43) | 0.54 (0.51-0.57) | 0.07 (0.05-0.08) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.98 (0.79-1.20) | 1.17 (0.74-1.87) | 0.41 (0.38-0.44) | 0.54 (0.51-0.57) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.82 (0.66-1.01) | 1.27 (0.79-2.03) | 0.37 (0.34-0.40) | 0.57 (0.54-0.61) | 0.06 (0.04-0.08) |

| Insulin use, %(n) | |||||

| No | -- | -- | 0.39 (0.37-0.41) | 0.56 (0.54-0.58) | 0.05 (0.05-0.06) |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.96-1.35) | 1.14 (0.79-1.64) | 0.41 (0.38-0.45) | 0.53 (0.50-0.56) | 0.06 (0.04-0.07) |

| Number of unique providers seen for E&Mc visits per quarter | |||||

| 0 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.41 (0.39-0.44) | 0.54 (0.51-0.56) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| 1 | 0.81 (0.72-0.90)** | 1.02 (0.81-1.29) | 0.37 (0.35-0.38) | 0.58 (0.56-0.60) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| 2 | 0.96 (0.85-1.09) | 1.07 (0.81-1.40) | 0.40 (0.38-0.43) | 0.54 (0.52-0.56) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| ≥3 | 1.07 (0.93-1.24) | 1.04 (0.75-1.44) | 0.43 (0.40-0.45) | 0.52 (0.49-0.55) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) |

| Any days in inpatient setting | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.38 (0.36-0.40) | 0.56 (0.55-0.58) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| Yes (ref) | 2.35 (2.02-2.74)** | 1.23 (0.86-1.77) | 0.57 (0.53-0.60) | 0.38 (0.35-0.42) | 0.05 (0.03-0.06) |

| Any 90-day prescription fills in the quarter | |||||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 0.41 (0.40-0.43) | 0.54 (0.52-0.56) | 0.04 (0.04-0.05) |

| Yes (ref) | 0.58 (0.47-0.71)** | 2.64 (1.88-3.70)** | 0.28 (0.24-0.31) | 0.60 (0.56-0.64) | 0.12 (0.10-0.15) |

| Last available A1cd prior to quarter | |||||

| <7% (ref) | -- | -- | 0.39 (0.37-0.41) | 0.56 (0.54-0.58) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| 7% to <9% | 1.00 (0.87-1.16) | 1.38 (1.03-1.87)* | 0.39 (0.36-0.41) | 0.55 (0.52-0.57) | 0.07 (0.05-0.08) |

| ≥9% | 1.59 (1.27-2.00)** | 0.98 (0.56-1.70) | 0.50 (0.45-0.54) | 0.46 (0.42-0.51) | 0.04 (0.02-0.06) |

| Not tested | 0.73 (0.53-1.01) | 1.18 (0.65-2.14) | 0.32 (0.27-0.38) | 0.61 (0.55-0.67) | 0.06 (0.03-0.09) |

| Last available LDLe prior to quarter | |||||

| <100 mg/dl (ref) | -- | -- | 0.35 (0.33-0.37) | 0.59 (0.56-0.61) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| 100-129 mg/dl | 1.19 (1.01-1.40)* | 0.96 (0.71-1.32) | 0.39 (0.36-0.42) | 0.55 (0.52-0.59) | 0.06 (0.04-0.07) |

| ≥130 mg/dl | 2.60 (2.08-3.24)** | 0.86 (0.46-1.62) | 0.57 (0.52-0.62) | 0.39 (0.35-0.44) | 0.04 (0.02-0.06) |

| Not tested | 1.47 (1.20-1.81)** | 0.94 (0.61-1.45) | 0.44 (0.40-0.48) | 0.51 (0.47-0.55) | 0.05 (0.02-0.07) |

| Last available BPf prior to quarter | |||||

| <130/80 (ref) | -- | -- | 0.42 (0.39-0.45) | 0.53 (0.50-0.56) | 0.05 (0.03-0.06) |

| (≥130/80) | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) | 1.23 (0.90-1.68) | 0.40 (0.38-0.41) | 0.55 (0.53-0.56) | 0.06 (0.05-0.07) |

| Missing | 0.71 (0.57-0.90)** | 0.88 (0.53-1.46) | 0.35 (0.31-0.39) | 0.60 (0.56-0.64) | 0.05 (0.03-0.06) |

p<.05

p<.01

CI = confidence interval; ref, reference group

ACG-PM = adjusted clinical groups – predictive model

E&M = evaluation and management

A1c = glycated hemoglobin

LDL = low-density lipoprotein

BP = blood pressure; mg/dl, milligrams per deciliter.

Table 3 provides odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjusted predicted probabilities from the same multinomial logistic regression model for predictors of quarterly undersupply versus appropriate supply. The factors emerging as significant predictors of greater odds of having an undersupply in a given quarter were largely distinct from those predicting an oversupply, and included minority race/ethnicity, greater baseline ACG-PM score, alcohol/drug abuse, having had an inpatient stay during the baseline period, and poor HbA1c control. Factors that were associated with reduced odds of having an undersupply included diagnosis with a psychotic disorder, taking 3-4 or 5-6 diabetes-related medications versus only 1-2 medications, having seen one versus zero providers in the quarter, and having at least one 90-day prescription fill during the quarter.

Results of the class-specific models (see Appendices) were substantively similar to the primary model results, although there was some variation in statistical significance of odds ratios across models. Notably, age-insurance status and having at least one 90-day fill in a quarter remained strongly associated with higher odds of oversupply versus appropriate supply, although the magnitude of odds ratios for the age-insurance status categories in the model of antihypertensive oversupply were somewhat attenuated.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies to examine medication oversupply in a typical U.S. practice and in both Medicare Part D enrollees and privately insured individuals. It also adds to a small literature base regarding the determinants of oversupply, by investigating a greater range of predisposing, enabling, and medical need factors – including payer type – that may contribute to oversupply. In 2,519 diabetes patients followed for 12,995 patient-quarters, oversupply of diabetes, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive medications was observed in 5.5% of all quarters and about 10% of all patients. This is notably less than reported in prior studies of Veterans,22,39,41 Medicaid enrollees,42 and other underserved patients receiving care in safety-net systems,14-16 where oversupply was observed in ~25-50% of patients taking these classes.

The lower prevalence of oversupply observed in this study of 2006-2008 claims, compared to past studies using older data (i.e., 1990s and early 2000s),14-16,22,39,41,43 may reflect payers’ increased use in recent years of computerized utilization management systems designed to prevent dispensing of oversupplies. Such computerized systems identify early refills and duplicate prescriptions within a subclass when patients attempt to obtain them at pharmacies. Subsequently, if these early refills and duplicate prescriptions are deemed clinically unjustified, they are prevented from being dispensed, mainly through lack of payment to the pharmacy from the payer. These systems would be particularly effective in curbing therapeutic duplication (i.e., concomitant/continued filling of two duplicative agents within a subclass), which is rarely clinically justified and has been previously shown in Medicaid plans to contribute more heavily to oversupply than early refilling of a single agent or a one-time switch between agents within a class.44 Although computerized systems may also identify these other drivers of oversupply, including early refills or one-time switches, these cases are more likely to be therapeutically justified and overridden by the pharmacist in conjunction with the payer.

Although the prevalence of oversupply was much lower in this study than in past investigations, there was considerable variability in oversupply associated with payer type. The highest predicted probability of oversupply was seen in individuals dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid receiving their prescription drug benefit through subsidized Part D PDPs (9% of such beneficiaries under 65 and 11% of those aged 65+), followed by Medicare-only enrollees (7% in beneficiaries under age 65 and 5% in those aged 65+) and finally privately insured individuals (2%). This may reflect greater clinical complexity in older and dually-eligible diabetes patients that raises the potential for prescribing practices that drive oversupply, including both one-time drug switches and therapeutic duplication. However, the large magnitude of the odds ratios for payer-age groups in this study was observed after controlling for multiple risk adjustment variables (i.e., ACG-PM risk score using all diagnosis codes, diabetes severity, and indicators for specific comorbidities) and remained robust in sensitivity analyses stratified by ACG-PM score and the presence of diabetes complications. Thus, it is unlikely that the observed differences in oversupply are driven entirely by differences in clinical complexity. Instead, differences in how computerized utilization management systems are used by pharmacists and payers when serving patients who face socio-economic barriers to accessing and appropriately using medications may play a role. It is possible that limits on early refills may be less strictly defined or enforced by payers serving socio-economically disadvantaged patients, due to a focus on reducing barriers to acquiring supplies of medications in patients who face cost and other logistical barriers to regularly accessing necessary medications. In addition, patient copays for commonly used antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antihypertensive agents in such systems are minimal-to-zero, further reducing disincentives to patients for filling of excess or early prescriptions. Although such practices may be essential to ensuring access to needed medications and reducing cost-related non-adherence in disadvantaged populations, they may also have the unintended consequence of increasing dispensing of excess medications.

Results also suggest that use of 90-day supplies may reduce undersupplies, but may also be an important driver of patients’ accumulation of oversupplies, independent of payer type. Although 90-day supplies may increase convenience and reduce gaps in medication coverage,45,46, they can also lead to oversupplies if patients switch strengths or agents within a medication subclass (e.g., rosiglitazone to pioglitazone) early after obtaining a 90-day refill of an initial medication (i.e., “leftovers”). Although some costs of oversupplies resulting from 90-day fills may be offset by reductions in dispensing costs, evidence on the net cost implications of 30- vs. 90-day supplies is conflicting. 45,46 There has also been little direct examination of whether 90-day supplies actually improve patients’ daily medication-taking behavior, even when they increase the number of days in which they possess the medication. In addition, having oversupplies of leftover medications associated with 90-day fills may further complicate already-complex medication regimens, and result in patient errors and adverse events. Future research should attempt to identify patient populations and circumstances in which 90-day supplies effectively reduce undersupply while not encouraging oversupply, and improve patterns of medication-taking behavior, and in which potential negative cost and safety outcomes of oversupply are minimized.

Findings of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Although a strong association of payer type with oversupply was observed, it was not possible to examine variation in oversupply among specific Medicare Part D PDPs, due to inclusion of a relatively small sample of individuals receiving care from a single provider group and resulting representation of a small number of Part D plans. The focus on a single provider group also makes it difficult to know how generalizable findings are to all Part D plans, including Medicare Advantage plans, and other provider groups. Larger, more geographically representative studies are needed to shed light on variation in oversupply among Part D plans and the role of different plan characteristics. In addition, use of a retrospective cohort design limits the ability to draw firm conclusions that the identified predictors of oversupply are causal factors. As noted above, it was not possible to fully disentangle the effects of age and insurance type, due to a lack of individuals aged 65 or older with private insurance. However, higher odds of oversupply were observed in individuals under age 65 with Medicare Part D coverage versus private coverage, after controlling for co-morbidity and healthcare utilization, making it less likely that the significant association of insurance to oversupply was due to residual confounding by age. Also, bias from loss-to-follow-up may be present due to variation in the length of follow-up among patients in the cohort. In addition, as previously noted, for patients using multiple drug subclasses within a therapeutic category (e.g., metformin and sulfonylurea), the average of the subclass-level medication supply values was used. This may have led to under-estimates of the prevalence of oversupply, for example, when patients acquired oversupply of only one of the subclasses within the therapeutic category. However, subclass-level analyses were not feasible due to relatively small numbers of patients taking each individual subclass. Finally, this study does not provide insight on whether patients used excess medications. An important direction for future research will be to understand patterns of actual medication-taking behavior exhibited by patients with oversupply, and resulting effects on clinical outcomes and experience of adverse events.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that there are meaningful variations in the extent to which patients accumulate oversupplies of medications used to treat diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, depending on insurance type as well as their access to 90-day supplies. Results suggest more research is warranted on plan characteristics and utilization management practices employed by different health plans and their effect on patients’ acquisition of oversupplies, as well as downstream effects of oversupplies on medication-taking behavior and clinical outcomes.

Highlights.

Predictors of medication oversupply in adults with diabetes were examined.

Claims and health record data were captured from a large academic physician group.

Oversupply was less common than in previous studies of integrated health systems.

Oversupply was more common in Medicare Part D versus private plan beneficiaries.

The occurrence of 90-day refills was also positively associated with oversupply.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported by Grant Number R21DK090634 (PI: C. Thorpe) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Additional support was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality through grants R21HS017646 (PI: M. Smith) and R01HS018368 (PI: M. Smith); the UW Health Innovation Program and Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through NCRR grant 1UL1RR025011 and now by the NCATS grant 9U54TR000021; AHRQ 5T32HS000083 (Dr. Everett); 1K23HL112907 (Dr. Johnson); and the UW Centennial Scholars Program (Dr. Johnson). The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Appendix

Appendix 1a.

Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Quarterly Undersupply and Oversupply of Anti-diabetic Medications (n=8,489 quarters)

| Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals APP (95% CI) | APP (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Undersupply | Oversupply | Oversupply | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | -- | -- | 7.1% (5.3-8.8) |

| Female | 1.10 (.91-1.33) | 0.93 (0.63-1.39) | 6.5% (5.1-7.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (ref) | -- | -- | 7.2% (6.0-8.4) |

| Black | 1.98 (1.36-2.89)** | 1.12 (0.48-2.62) | 6.3% (1.9-10.6) |

| Other/Unknown | 1.74 (1.18-2.56)** | 0.27 (0.11-0.68)** | 1.8% (0.3-3.3) |

| Age and Insurance Status | |||

| HMO coverage only, any age (ref) | -- | -- | 2.6% (1.3-3.9) |

| Age <65 in Medicare only | 0.86 (0.57-1.27) | 5.77 (2.79-11.96)** | 13.1% (7.7-18.5) |

| Age <65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 0.85 (0.60-1.21) | 4.64 (2.14-10.09)** | 10.9% (6.0-15.9) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare only | 0.93 (0.73-1.18) | 2.31 (1.26-4.26)** | 5.8% (4.3-7.3) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 1.01 (0.69-1.47) | 7.24 (3.54-14.8)** | 15.0% (9.4-20.1) |

| Baseline ACG-PM score | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.7% (4.4-8.9) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.00 (0.83-1.21) | 0.97 (0.65-1.43) | 6.5% (4.9-8.1) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.09 (0.86-1.37) | 1.16 (0.71-1.90) | 7.4% (4.9-10.5) |

| Quartile 4 | 1.51 (1.13-2.01)** | 1.06 (0.61-1.83) | 6.2% (4.3-8.0) |

| Diabetes Complications | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.5% (5.3-7.6) |

| Yes | 1.02 (0.78-1.34) | 1.24 (0.76-2.01) | 7.7% (4.9-10.5) |

| Depression | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.0% (5.9-8.2) |

| Yes | 1.40 (1.04-1.89)* | 0.76 (0.41-1.39) | 4.9% (2.5-7.4) |

| Dementia | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.6% (5.5-7.6) |

| Yes | 0.92 (0.57-1.50) | 1.55 (0.71-3.39) | 9.7% (3.6-15.8) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.9% (5.8-8.0) |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.62-2.08) | 0.12 (0.02-0.92)* | 0.9% (0-2.3) |

| Psychoses | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.5% (5.3-7.6) |

| Yes | 0.77 (0.53-1.12) | 1.22 (0.66-2.27) | 8.3% (4.4-12.2) |

| Total number of diabetes-related medications at baseline | |||

| 1-2 (ref) | -- | -- | 4.9% (2.2-7.5) |

| 3-4 | 0.61 (0.46-0.80)* | 1.35 (0.70-2.60) | 7.5% (5.7-9.2) |

| 5-6 | 0.60 (0.43-0.82) | 1.31 (0.64-2.68) | 7.3% (5.4-9.2) |

| ≥7 | 0.89 (0.60-1.32) | 0.97 (0.41-2.31) | 4.9% (2.5-7.3) |

| Total number of unique medications (all types) at baseline | |||

| 0-5 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.4% (3.8-8.9) |

| 6-10 | 1.31 (1.02-1.68)* | 1.07 (0.62-1.84) | 6.2% (4.7-7.8) |

| 11-15 | 1.30 (0.93-1.82) | 1.21 (0.64-2.29) | 7.0% (4.6-9.4) |

| ≥16 | 1.43 (0.91-2.27) | 1.65 (0.77-3.54) | 8.8% (4.9-12.8) |

| K-index for study period | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 4.5% (3.0-6.0) |

| Quartile 2 | 0.73 (0.56-0.95) | 1.63 (0.98-2.72) | 7.6% (5.2-10.0) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.76 (0.59-0.99) | 1.73 (1.07-2.79)* | 7.9% (5.8-10.0) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.78 (0.61-1.02) | 1.35 (0.80-2.27) | 6.3% (4.3-8.4) |

| Insulin use, %(n) | |||

| No | -- | -- | 6.9% (5.7-8.2) |

| Yes | 1.49 (1.19-1.87)* | 0.97 (0.62-1.53) | 5.9% (3.8-8.1) |

| Number of unique providers seen for E&M visits per quarter | |||

| 0 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.2% (4.7-7.8) |

| 1 | 0.79 (0.69-0.90)** | 1.01 (0.78-1.31) | 6.7% (5.5-8.0) |

| 2 | 0.95 (0.81-1.11) | 1.21 (0.89-1.64) | 7.5% (5.9-9.0) |

| ≥3 | 1.00 (0.83-1.21) | 1.02 (0.69-1.49) | 6.3% (4.6-8.0) |

| Any days in inpatient setting | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.9% (5.8-8.1) |

| Yes (ref) | 2.07 (1.69-2.55)** | 0.85 (0.57-1.27) | 4.6% (2.9-6.2) |

| Any 90-day prescription fills in the quarter | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.7% (4.4-6.9) |

| Yes (ref) | 0.65 (0.50-0.83)** | 2.24 (1.54-3.26)** | 12.7% (9.5-15.8) |

| Last available A1c prior to quarter | |||

| <7% (ref) | -- | -- | 5.7% (4.4-6.9) |

| 7% to <9% | 1.03 (0.87-1.23) | 1.73 (1.25-2.39)** | 9.0% (7.2-10.8) |

| ≥9% | 1.52 (1.14-2.03)** | 0.61 (0.32-1.17) | 3.1% (1.4-4.9) |

| Not tested | 0.83 (0.51-1.34) | 0.82 (0.34-2.01) | 5.0% (1.1-8.9) |

p<.05

p<.01

Appendix 1b.

Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Quarterly Undersupply and Oversupply of Antihyperlipidemic Medications (n=8,770)

| Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals | APP (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Undersupply | Oversupply | Oversupply | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | -- | -- | 6.6% (5.0-8.2) |

| Female | 1.15 (0.96-1.39) | 0.74 (0.51-1.08) | 4.9% (3.8-5.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (ref) | -- | -- | 5.6% (4.6-6.5) |

| Black | 1.95 (1.32-2.89)** | 0.68 (0.24-1.95) | 3.1% (0.2-6.1) |

| Other/Unknown | 1.64 (1.08-2.50)* | 1.91 (0.79-4.63) | 8.4% (2.5-14.3) |

| Age and Insurance Status | |||

| HMO coverage only, any age (ref) | -- | -- | 2.5% (1.3-3.6) |

| Age <65 in Medicare only | 0.98 (0.68-1.42) | 3.64 (1.70-7.79)** | 8.0% (4.3-11.8) |

| Age <65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | 2.27 (1.08-4.77)* | 5.3% (2.7-7.9) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare only | 0.87 (0.69-1.10) | 2.41 (1.34-4.32)** | 5.8% (4.3-7.2) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 0.69 (0.47-1.01) | 5.15 (2.43-10.90)** | 11.7% (6.6-16.8) |

| Baseline ACG-PM score | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 7.5% (4.7-10.3) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.02 (0.84-1.24) | 0.73 (0.45-1.16) | 5.7% (3.9-4.5) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.08 (0.86-1.35) | 0.85 (0.51-1.43) | 6.4% (4.8-8.1) |

| Quartile 4 | 1.33 (1.01-1.76)* | 0.56 (0.31-1.02) | 4.2% (3.0-5.4) |

| Diabetes Complications | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.6% (4.5-6.6) |

| Yes | 1.24 (0.97-1.59) | 1.10 (0.68-1.77) | 5.7% (3.6-7.7) |

| Depression | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.7% (4.7-6.8) |

| Yes | 1.15 (0.86-1.54) | 0.89 (0.50-1.57) | 4.9% (2.7-7.2) |

| Dementia | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.5% (4.6-6.4) |

| Yes | 1.20 (0.76-1.90) | 1.37 (0.68-2.75) | 6.9% (3.0-10.8) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.7% (4.7-6.6) |

| Yes | 1.41 (0.73-2.72) | 0.44 (0.12-1.62) | 2.4% (0-5.4%) |

| Psychoses | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 4.7% (3.9-5.6) |

| Yes | 0.64 (0.45-0.91)* | 2.77 (1.59-4.82)** | 12.6% (7.6-17.5) |

| Total number of diabetes-related medications at baseline | |||

| 1-2 (ref) | -- | -- | 5.5% (2.6-8.4) |

| 3-4 | 0.68 (0.52-0.91)** | 0.96 (0.49-1.86) | 6.0% (4.4-7.5) |

| 5-6 | 0.64 (0.47-0.87)** | 0.92 (0.46-1.84) | 5.8% (4.4-7.3) |

| ≥7 | 0.68 (0.46-0.99)* | 0.63 (0.27-1.43) | 4.1% (2.3-5.9) |

| Total number of unique medications (all types) at baseline | |||

| 0-5 (ref) | -- | -- | 3.3% (1.7-4.9) |

| 6-10 | 1.01 (0.78-1.30) | 1.78 (1.02-3.10)* | 5.6% (4.3-6.9) |

| 11-15 | 1.11 (0.81-1.53) | 1.83 (0.87-3.83) | 5.6% (3.4-7.8) |

| ≥16 | 0.89 (0.59-1.34) | 3.09 (1.40-6.80)** | 9.3% (5.5-13.1) |

| K-index for study period | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 4.7% (2.9-6.5) |

| Quartile 2 | 0.99 (0.77-1.28) | 1.48 (0.87-2.53) | 6.7% (4.8-8.5) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.90 (0.70-1.15) | 1.09 (0.63-1.90) | 5.2% (3.7-6.8) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.73 (0.56-0.95)* | 1.13 (0.64-2.00) | 5.7% (3.8-7.6) |

| Insulin use, %(n) | |||

| No | -- | -- | 5.1% (4.0-6.1) |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.76-1.14) | 1.37 (0.93-2.01) | 6.8% (5.0-8.6) |

| Number of unique providers seen for E&M visits per quarter | |||

| 0 (ref) | -- | -- | 5.2% (3.9-6.6) |

| 1 | 0.84 (0.73-0.96)** | 1.03 (0.77-1.37) | 5.6% (4.5-6.8) |

| 2 | 0.94 (0.80-1.10) | 1.03 (0.74-1.42) | 5.5% (4.2-6.7) |

| ≥3 | 0.95 (0.79-1.14) | 1.12 (0.77-1.64) | 5.9% (4.5-7.3) |

| Any days in inpatient setting | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.8% (4.8-6.7) |

| Yes (ref) | 2.35 (1.95-2.83)** | 0.97 (0.65-1.45) | 4.2% (2.7-5.7) |

| Any 90-day prescription fills in the quarter | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 4.3% (3.5-5.2) |

| Yes (ref) | 0.79 (0.62-1.01) | 3.42 (2.40-4.89)** | 13.1% (9.9-16.3) |

| Last available LDL prior to quarter | |||

| <100 mg/dl (ref) | -- | -- | 6.1% (5.0-7.2) |

| 100-129 mg/dl | 1.52 (1.25-1.86)** | 1.12 (0.74-1.68) | 6.0% (4.0-8.0) |

| ≥130 mg/dl | 3.98 (3.02-5.24)** | 0.56 (0.23-1.35) | 2.1% (0.4-3.8) |

| Not tested | 1.48 (1.11-1.96)** | 0.91 (0.56-1.49) | 5.1% (3.0-7.1) |

p<.05

p<.01

Appendix 1c.

Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Quarterly Undersupply and Oversupply of Antihypertensive Medications (n=11,181 quarters).

| Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals | APP (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Undersupply | Oversupply | Oversupply | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | -- | -- | 7.8% (6.2-9.4) |

| Female | 1.08 (0.91-1.28) | 0.92 (0.67-1.26) | 7.1% (5.8-8.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (ref) | -- | -- | 7.2% (6.2-8.2) |

| Black | 1.85 (1.31-2.62)** | 1.46 (0.74-2.86) | 8.0% (3.7-12.4) |

| Other/Unknown | 2.36 (1.58-3.52)** | 2.21 (1.05-4.65)* | 10.3% (4.4-16.2) |

| Age and Insurance Status | |||

| HMO coverage only, any age (ref) | -- | -- | 3.9% (2.4-5.5) |

| Age <65 in Medicare only | 1.10 (0.78-1.55) | 1.65 (0.81-3.36) | 6.1% (2.9-9.3) |

| Age <65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 1.08 (0.79-1.48) | 2.32 (1.27-4.24)** | 8.3% (5.2-11.3) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare only | 1.09 (0.87-1.37) | 2.25 (1.40-3.63)** | 8.0% (6.4-9.7) |

| Age ≥65 in Medicare and Medicaid | 1.19 (0.86-1.64) | 3.74 (2.05-6.84)** | 12.1% (16.1) |

| Baseline ACG-PM score | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | -- | 7.5% (5.3-9.8) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.10 (0.91-1.33) | 1.12 (0.78-1.61) | 8.1% (6.3-9.8) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.37 (1.10-1.72)** | 1.08 (0.72-1.63) | 7.3% (5.8-8.9) |

| Quartile 4 | 2.05 (1.59-2.63)** | 1.23 (0.76-2.00) | 7.1% (5.4-8.9) |

| Diabetes Complications | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.6% (6.4-8.8) |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.75-1.15) | 0.85 (0.57-1.26) | 6.8% (4.8-8.7) |

| Depression | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.2% (6.1-8.3) |

| Yes | 1.06 (0.81-1.37) | 1.28 (0.78-2.09) | 8.7% (5.5-12.0) |

| Dementia | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.2% (6.2-8.2) |

| Yes | 1.02 (0.71-1.47) | 1.52 (0.85-2.71) | 10.2%(5.5-15.0) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.6% (6.5-8.6) |

| Yes | 1.58 (1.00-2.49) | 0.58 (0.19-1.75) | 3.9% (0-7.8) |

| Psychoses | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 6.9% (5.9-7.9) |

| Yes | 0.76 (0.56-1.05) | 1.69 (1.02-2.80)* | 11.6% (7.3-16.0) |

| Total number of diabetes-related medications at baseline | |||

| 1-2 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.2% (3.9-8.6) |

| 3-4 | 0.68 (0.53-0.86)** | 0.95 (0.58-1.56) | 6.8% (5.4-8.3) |

| 5-6 | 0.64 (0.49-0.83)** | 1.28 (0.76-2.17) | 9.1% (7.1-11.0) |

| ≥7 | 0.73 (0.52-1.03) | 0.84 (0.42-1.67) | 5.9% (3.3-8.6) |

| Total number of unique medications (all types) at baseline | |||

| 0-5 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.4% (4.1-8.7) |

| 6-10 | 1.23 (0.97-1.56) | 1.21 (0.76-1.93) | 7.1% (5.7-8.5) |

| 11-15 | 1.27 (0.93-1.72) | 1.31 (0.76-2.28) | 7.5% (5.5-9.6) |

| ≥16 | 1.46 (0.98-2.17) | 1.90 (1.01-3.58)* | 9.9% (6.3-13.4) |

| K-index for study period | |||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | -- | 6.8% (4.9-8.6) | |

| Quartile 2 | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) | 1.18 (0.76-1.81) | 8.0% (5.9-10.1) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.01 (0.80-1.29) | 1.08 (0.71-1.64) | 7.2% (5.4-9.0) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.78 (0.61-0.99)* | 1.04 (0.68-1.59) | 7.6% (5.6-9.6) |

| Insulin use, %(n) | |||

| No | -- | -- | 7.3% (6.2-8.5) |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.94-1.36) | 1.10 (0.78-1.54) | 7.6% (5.7-9.5) |

| Number of unique providers seen for E&M visits per quarter | |||

| 0 (ref) | -- | -- | 7.0% (5.5-8.4) |

| 1 | 0.94 (0.83-1.06) | 1.19 (0.95-1.49) | 8.3% (6.9-9.6) |

| 2 | 1.06 (0.92-1.22) | 1.02 (0.78-1.32) | 7.0% (5.7-8.2) |

| ≥3 | 1.12 (0.95-1.32) | 1.04 (0.78-1.40) | 7.0% (5.6-8.3) |

| Any days in inpatient setting | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 7.5% (6.5-8.6) |

| Yes (ref) | 2.04 (1.74-2.38)* | 1.18 (0.86-1.61) | 6.7% (4.8-8.5) |

| Any 90-day prescription fills in the quarter | |||

| No (ref) | -- | -- | 5.9% (4.9-6.8) |

| Yes (ref) | 0.56 (0.44-0.71)** | 2.77** (2.00-3.82) | 16.5% (13.0-20.0) |

| Last available BP prior to quarter | |||

| <130/80 (ref) | -- | -- | 6.2% (4.6-7.7) |

| (≥130/80 | 0.79 (0.68-0.92)** | 1.16 (0.87-1.54) | 7.6% (6.6-8.7) |

| Missing | 0.78 (0.60-1.00) | 1.18 (0.73-1.91) | 7.8% (5.1-10.5) |

p<.05

p<.01

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta (GA): 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RW, Devita NG, Singer DE, Meigs JB. Polypharmacy and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003 May 1;26:1408–1412. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1408. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2007. Diabetes Care. 2007 Jan;30:S4–S41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cholesterol Education Program Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odegard PS, Capoccia K. Medication taking and diabetes: A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ. 2007 Nov-Dec;33:1014–1029. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308407. discussion 1030-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrischilles E, Rubenstein L, Van Gilder R, Voelker M, Wright K, Wallace R. Risk factors for adverse drug events in older adults with mobility limitations in the community setting. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007 Jan;55:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang ES. Appropriate application of evidence to the care of elderly patients with diabetes. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2007 Nov;3:260–263. doi: 10.2174/1573399810703040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003 May;51:S265–S280. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004 Sep;27:2285–2285. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosworth HB. Medication treatment adherence. In: Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, editors. Patient Treatment Adherence: Concepts, Interventions, and Measurement. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 147–194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Medication adherence in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann. Pharmacother. 2001 May;35:539–545. doi: 10.1345/aph.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balkrishnan R, Rajagopalan R, Camacho FT, Huston SA, Murray FT, Anderson RT. Predictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Ther. 2003 Nov;25:2958–2971. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pladevall M, Williams LK, Potts L, Divine G, Xi H, Lafata JE. Clinical outcomes and adherence to medications measured by claims data in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2800–2805. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroupe KT, Teal EY, Tu W, Weiner M, Murray MD. Association of refill adherence and health care use among adults with hypertension in an urban health care system. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:779–789. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroupe KT, Teal EY, Weiner M, Gradus-Pizlo I, Brater DC, Murray MD. Health care and medication costs and use among older adults with heart failure. Am. J. Med. 2004 Apr 1;116:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroupe KT, Murray MD, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Association between medication supplies and healthcare costs in older adults from an urban healthcare system. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000 Jul;48:760–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krigsman K, Melander A, Carlsten A, Ekedahl A, Nilsson JL. Refill non-adherence to repeat prescriptions leads to treatment gaps or to high extra costs. Pharm. World Sci. 2007 Feb;29:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s11096-005-4797-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans JM, Donnan PT, Morris AD. Adherence to oral hypoglycaemic agents prior to insulin therapy in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2002 Aug;19:685–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morningstar BA, Sketris IS, Kephart GC, Sclar DA. Variation in pharmacy prescription refill adherence measures by type of oral antihyperglycaemic drug therapy in seniors in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002 Jun;27:213–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spoelstra JA, Stolk RP, Heerdink ER, et al. Refill compliance in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A predictor of switching to insulin therapy? Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2003 Mar;12:121–127. doi: 10.1002/pds.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson K, Melander A, Svensson C, Lind O, Nilsson JLG. Repeat prescriptions: refill adherence in relation to patient and prescriber characteristics, reimbursement level and type of medication. Eur. J. Public Health. 2005 Dec;15:621–626. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe CT, Bryson CL, Maciejewski ML, Bosworth HB. Medication acquisition and self-reported adherence in veterans with hypertension. Med. Care. 2009 Apr;47:474–481. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e31818e7d4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997 Jan;50:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert PL, Geiss LS, Tierney EF, Engelgau MM, Yawn BP, McBean AM. Identifying persons with diabetes using Medicare claims data. Am. J. Med. Qual. 1999 Nov-Dec;14:270–277. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu BN, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N. Engl. J. Med. Mar. 2007;356:1130–1139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kautter J, Pope GC, Trisolini M, Grund S. Medicare Physician Group Practice demonstration design: Quality and efficiency pay-for-performance. Health Care Financ. Rev. Fall. 2007;29:15–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorpe CT, Flood GE, Kraft SA, Everett CM, Smith MA. Effect of patient selection method on provider group performance estimates. Med. Care. 2011;49:780–785. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality. WCHQ Ambulatory Measure Specification: Postpartum Care Performance Measures. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryson CL, Au DH, Young B, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. A refill adherence algorithm for multiple short intervals to estimate refill compliance (ReComp). Med. Care. 2007 Jun;45:497–504. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180329368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2009 Jul;15:457–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blalock SJ. The theoretical basis for practice-relevant medication use research: patient-centered/behavioral theories. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2011 Dec;7:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Oddone EZ. Improving blood pressure control by tailored feedback to patients and clinicians. Am. Heart J. 2005 May;149:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray MD, Morrow DG, Weiner M, et al. A conceptual framework to study medication adherence in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2004 Mar;2:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(04)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ejlertsson G, Berg S. Continuity-of-care measures. An analytic and empirical comparison. Med. Care. 1984 Mar;22:231–239. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buccaneer Computer Systems & Service, Inc. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse User Manual. Buccaneer Computer Systems & Service, Inc.; Warrenton, VA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med. Care. 1998 Jan;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2010. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jan;33:S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang M, Barner JC, Worchel J. Factors related to antipsychotic oversupply among Central Texas Veterans. Clin. Ther. 2007 Jun;29:1214–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers WH. SG17: regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1993;13:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campione JR, Sleath B, Biddle AK, Weinberger M. The influence of physicians’ guideline compliance on patients’ statin adherence: a retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2005 Dec;3:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farley JF, Wang CC, Hansen RA, Voils CI, Maciejewski ML. Continuity of antipsychotic medication management for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011 Jul;62:747–752. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farley JF, Wang CC, Hansen RA, Voils CI, Maciejewski ML. Continuity of antipsychotic medication management for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2011 Jul;62:747–752. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin BC, Wiley-Exley EK, Richards S, Domino ME, Carey TS, Sleath BL. Contrasting measures of adherence with simple drug use, medication switching, and therapeutic duplication. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009 Jan;43:36–44. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taitel M, Fensterheim L, Kirkham H, Sekula R, Duncan I. Medication days’ supply, adherence, wastage, and cost among chronic patients in Medicaid. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2012;2:E1–E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.002.03.a04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Domino ME, Martin BC, Wiley-Exley E, et al. Increasing time costs and copayments for prescription drugs: an analysis of policy changes in a complex environment. Health Serv. Res. 2011 Jun;46:900–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]