Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of behavioral counseling interventions in reducing sexual risk behaviors and HIV/STI prevalence in low- and middle-income countries. A systematic review of papers published between 1990 and 2011 was conducted, identifying studies that utilized either a multi-arm or pre-post design and presented post-intervention data. Standardized methods of searching and data abstraction were used, and 30 studies met inclusion criteria. Results are summarized by intervention groups: a) people living with HIV; b) people who use drugs and alcohol; c) serodiscordant couples; d) key populations for HIV prevention; and e) people at low to moderate HIV risk. Evidence for the effectiveness of behavioral counseling was mixed, with more rigorously designed studies often showing modest or no effects. Recommendations about the use of behavioral counseling in developing countries are made based on study results and in light of the field’s movement towards combination prevention programs.

Keywords: HIV prevention, behavioral counseling, low-income countries, middle-income countries, systematic review

Introduction

The HIV epidemic has overwhelmingly burdened populations in low- and middle-income countries. UNAIDS has identified several priorities to combat the HIV epidemic, including increasing the availability of antiretroviral medications and reducing sexual transmission of HIV (1). Specifically, UNAIDS has set a goal of “Zero New Infections” by 2015 with a strategic plan that will offer widespread access to effective prevention programming. This ambitious endeavor requires identification of best practices in HIV prevention to inform program and policy decisions.

Behavioral counseling (BC) programs represent one approach to HIV prevention at an individual level. A major goal of these programs is to reduce the frequency of high-risk behaviors that ultimately lead to infection, including risky sexual behaviors. Though the specifics of BC approaches vary, these interventions generally involve client-centered interactions that aim to eliminate or reduce HIV-related risk behaviors through provision of both individualized risk reduction planning and behavioral strategies.

Over a decade ago, UNAIDS released an international review of BC strategies and identified many approaches that appeared to decrease sexual risk behaviors (2). At the time, a large proportion of rigorously designed BC studies had been conducted in the U.S., with more smaller-scale “grassroots” efforts seen in low- and middle-income countries. The authors noted that few programs that showed efficacy had been operationalized at the large-scale level necessary to sustain a lasting preventive impact. During the decade following this report, more rigorously designed research has evaluated BC in middle- and low-income countries in a broad range of delivery settings and regions and among various target groups. BC has been adapted for people living with HIV (PLHIV) (e.g., (3)) and certain key populations (e.g., (4)) but has also been provided as primary prevention to relatively low-risk groups (e.g., (5)). Based on their review of research, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed high-intensity BC for populations at known risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) to be cost-effective in the U.S. (6); however, they caution against primary prevention for low-risk groups due to the lack of empirical evidence and the potential for high costs. Given higher HIV prevalence rates relative to the U.S. and fewer funds for intervention, these same recommendations may not apply to low- and middle-income countries.

Past reviews have examined the efficacy of more broadly defined preventive interventions, which included but were not limited to BC, in Latin American, Caribbean, and Asian countries (7, 8). These reviews found positive but widely variable effects across studies. Other reviews have summarized the efficacy of HIV counseling and testing, with similar conclusions (9, 10, 11, 12). Despite the proliferation of more intensive BC approaches in low- and middle-income countries, the evidence to support their efficacy has not been systematically reviewed. Thus, the current review aims to summarize existing data on the effectiveness of BC in reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors and biological outcomes in these settings. Further, information about target populations, intervention characteristics (e.g., theoretical orientation, length, provider), and study characteristics is summarized and discussed.

Method

This review was conducted as part of The Evidence Project, which conducts systematic reviews of behavioral interventions targeting HIV prevention in low and middle-income countries. We follow standardized methods for reporting consistent with established guidelines (13).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We first specified a definition and theoretical framework for BC. Interventions had to: (1) include an interactive session(s), (2) be led by a trained counselor with a client(s), (3) use an approach that is “client centered” and, (4) specifically focus on HIV risk behaviors. Client-centered was defined as: a) talking with rather than to the client; b) face to face meetings; c) sessions that are responsive to needs identified by the client, and d) maintaining a neutral non-judgmental attitude towards clients.

Using this definition, we established the following inclusion criteria: a) the intervention must focus on HIV prevention or measure HIV-related outcomes; b) the intervention must meet the definition of BC above; c) specific outcomes of interest are presented; d) the study is conducted in a low- or middle-income country as classified by the World Bank (14); e) a multi-arm or pre-post study design was employed; and f) post-intervention data are presented. Studies examining solely the counseling associated with HIV testing were excluded (i.e., Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT); Provider Initiated Testing and Counseling), as these have been systematically reviewed separately by our group (10, 11). Of note, some of the BC interventions included in this review were conducted at VCT centers but provided counseling interventions above and beyond standard VCT. Specific outcomes of interest for this review were sexual behavior (not simply intentions), including condom use, number of sexual partners, frequency of sexual behaviors, and prevalence or incidence of HIV or STIs.

Search Strategy

The following electronic databases were searched using the date ranges January 1, 1990 to May 9, 2011: PubMed, CINHAL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts. Search terms included combinations of terms for BC, HIV, and low- and middle-income countries; a full list is available from the corresponding author upon request. Secondary reference searching was conducted on all included studies, and hand searching was conducted on the table of contents of four journals: AIDS, AIDS and Behavior, AIDS Care, and AIDS Education and Prevention. Finally, the reference list of several past reviews of similar topics were hand searched for relevant studies (7, 8, 9).

Screening Abstracts

Titles, abstracts, citation information, and descriptor terms of citations identified through the search strategy were screened in a two-step process. First, study staff screened records individually to remove clearly non-relevant records. Second, two study team members screened remaining records independently and compared results. Full text articles were obtained for all selected records, and two independent reviewers again assessed full-text articles for eligibility. Differences at each stage were resolved through consensus. During the screening process, we discovered that papers sometimes did not provide enough descriptive information about the BC interventions to determine whether they met all four aspects of the pre-specified definition for “client-centered.” Rather than exclude studies without sufficient information, we instead included studies as long as: a) they met at least two aspects of the client-centered definition and b) there was no clear evidence that the intervention was not client-centered (e.g., a strictly didactic intervention with no client participation).

Data Extraction and Management

For each included study, data were extracted independently by two trained coders using standardized extraction forms. The coding forms and manual for this project are available upon request. Differences were resolved through consensus and were referred to a senior study team member when necessary. The following information was gathered from each study: location, setting, and target group; period of the study; intervention description; study design; sample size; age; gender; sampling strategy; length of follow-up and completion rates; outcome measures; statistical tests; effect sizes; significance levels; and limitations described by both authors and reviewers. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria but presented information relevant to behavioral counseling were coded as background material using a simplified data abstraction form.

Study Rigor

The rigor of the design for included studies was assessed by means of eight criteria: (i) prospective cohort; (ii) control or comparison group; (iii) pre-/post-intervention data; (iv) random assignment of participants to the intervention; (v) random selection of subjects for assessment or assessment of all subjects who participated in the intervention; (vi) follow-up rate of 80% or more; (vii) comparison groups equivalent on socio-demographic measures; and (viii) comparison groups equivalent at baseline on outcome measures.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed according to coding categories and outcomes. Descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies or means) were calculated for each of the coded study characteristics. Meta-analysis was not conducted, as only 4 of the 30 studies reported the requisite statistical results (4, 15–17) and because there was notable heterogeneity of intervention modalities and measured outcomes.

Results

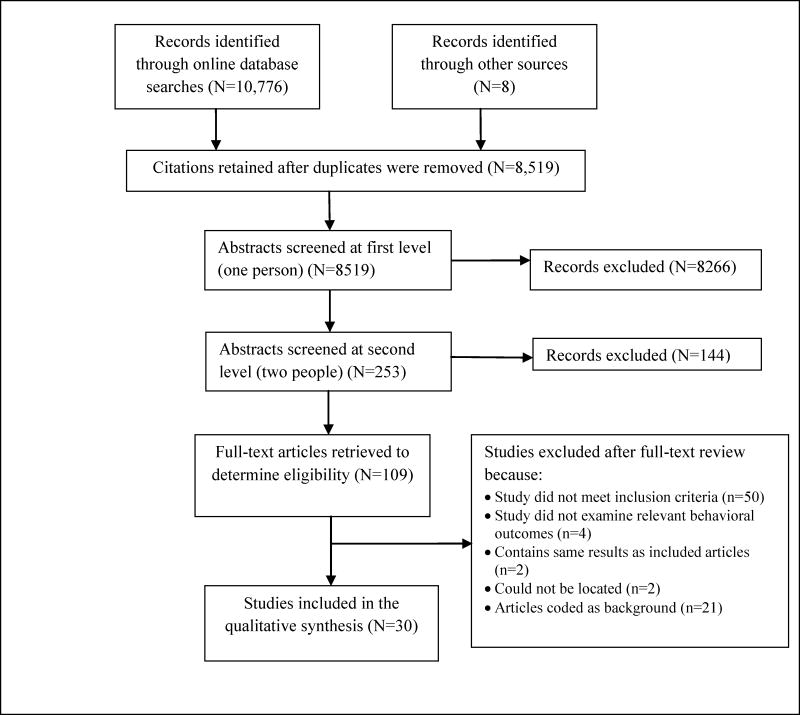

The initial database search yielded 10,776 records; 8 additional records were identified through other means (see Figure 1). Once duplicates were removed, 8,519 records underwent initial screening, 253 records were retained for screening in duplicate, and 109 underwent full-text review. Of these, 50 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria, 4 did not examine relevant behavioral outcomes, 2 contained the same results as other included articles, 2 could not be located, and 21 were coded as background. The remaining 30 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Counseling: Disposition of Study Records

Table 1 describes the included studies. The majority (n=19) were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, including South Africa (n=9), Zambia (n=4), Kenya (n=3), Tanzania (n=1), Nigeria (n=1), and Zaire/ Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (n=1). Remaining studies were conducted in China (n=4), Thailand (n=2), Mexico (n=1), Russia (n=1), Malaysia (n=1), Bolivia (n=1), and India (n=1).

Table 1.

Studies included in the systematic review of Behavioral Counseling interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries

| Study | Setting | Sample | Intervention | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample: People Living with HIV | |||||

| Cornman et al., 2008 (3) | South Africa An urban HIV care clinic, delivered by trained Antiretroviral (ARV) Adherence Counselors |

152 HIV-infected adults |

Description: Brief patient-centered discussions during routine clinical visits. Used an 8-step framework to target patient’s specific HIV risk behaviors. Motivational interviewing techniques were used to promote behavior change and negotiate a risk reduction action plan. Based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model of HIV prevention. Length: Delivered as part of all routine clinical visits over a 6 month period (mean number of visits per patient was 2.5). Discussions lasted 15 minutes. |

RCT. Comparison group was a standard of care control. Assessments at BL and 6 month FU. |

Unprotected sex, past 3 months: BL: 2.64 in IV group, 2.26 for control 6 month FU: 0.40 in IV group, 3.85 for control Time X Condition interaction (ANOVA): b = −2.24, p = 0.016 Number of sex acts, past 3 months: Time X Condition interaction, ns |

| Futterman et al., 2010 (23) | South Africa Maternity clinics, delivered by trained HIV-positive mothers |

160 HIV-positive pregnant women (n = 71 at follow-up) |

Description: The Mamekhaya program combined an existing peer mentoring program (Mothers2mothers) with a cognitive behavioral intervention. Participants were paired with HIV-positive mentor mothers who provided support and HIV-related education. The cognitive behavioral intervention was delivered in a group format and consisted of didactics, paired and group discussions, role plays, and a review of recent experiences related to living with HIV, preventing transmission, and treatment adherence. Length: Mentoring was delivered during pregnancy and the weeks following delivery. CBT groups met 8 times. |

Comparison of IV and control site (sites non randomly assigned to condition). Control received standard prevention of mother-to-child transmission treatment (PMTCT), intervention group received PMTCT plus the Mamekhaya progam. Assessments at BL and 6 month FU. |

Abstinent or always uses a condom (at 6 month FU): 97.4% of IV group, 96.8% of control group, Interaction X follow-up interaction B=.24, ns (Logit) |

| Jones et al., 2004 (22) | Zambia A hospital-based Voluntary Counseling and Testing Center. Delivered by registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and other trained healthcare staff |

150 sexually active adult women (50% HIV positive) |

Description: Both group and individual formats included information on HIV/STD transmission, cognitive behavioral skills training to increase protected sex, and discussion of reactions to barrier protection, cognitive reframing, and sexual negotiation. Videos demonstrating the correct methods for barrier use and written materials were utilized. Participants were provided with male and female condoms and vaginal chemical products. Length: Three monthly 2-hour sessions (for both the group and individual intervention) |

RCT. Random assignment to group, individual, or usual care. Usual care was pre- and post-HIV test counseling and supplies of condoms and vaginal chemical products. Assessments at BL and 3-, 4- and 6-month FU. |

Overall practice of protected sex: At 6 month FU, group format showed a greater increase in protected sex practices (χ2=9.5, p<.001) than other groups (individual or control). Use of male condoms: At 6 month FU, group format showed a greater increase in condom use (χ2=7.3, p<.001) than other groups. |

| Jones et al., 2006 (21) | Zambia A hospital-based Voluntary Counseling and Testing Center. Delivered by licensed nurses and healthcare staff. |

240 sexually active HIV positive adult women |

Description: The group intervention consisted of education on HIV prevention (e.g., safe sex, reproductive choice); cognitive behavioral skills training as applied to sexual behavior and negotiation; provision of and instruction about condoms, vaginal lubricants, gels and suppositories; and demonstration of male and female condoms and practice with videos and models. Groups were limited to 10 women. The individual intervention was conducted in a traditional health education format and included the same information and materials as the group format. Length: The group arm consisted of three 2-hour sessions. The individual arm also attended three sessions but length of the sessions was not indicated. |

RCT. Participants randomized to either individual or group intervention. Assessments at BL and 4-, 5-, 6-, and 12-month FU. |

Results at 12 Month FU Sex X Time X Group Interactions Overall Barrier Use F=.50, ns Use of Male Condoms F=.24, ns Use of Female Condoms F=2.8, ns |

| MacNeil et al., 1999 (24) | Tanzania Delivered in a counseling center or in the home. Information about counselors not reported. |

154 newly diagnosed HIV+ adults |

Description: Counseling on prevention and problem solving for the HIV+ individual, education to other family members, provision of condoms, and when necessary referral to other services. Length: At least once per month for 6 months |

RCT. Control group received regular health services. Assessments at BL and 3- and 6-month FU. |

Use a condom for last sexual intercourse: IV group: BL=17/77, 6 month FU=49/77 C group: BL=7/77, 6 month FU=34/77 Between group differences not significant STI symptoms-pain, burning, or discharge on urination Between group differences not significant STI symptoms-genital sores Between group differences not significant |

| Olley, 2006 (25) | Nigeria Voluntary counseling and testing center. Trained counselors. |

67 HIV+ adults |

Description: Individual dyadic instruction focused on the cause and course of HIV/AIDs, its psychosocial impact, and self-management skills. Length: Four weekly 60-minutes sessions |

RCT using a waitlist control condition that received only supportive counseling during the study period. Assessments at baseline, post-treatment, and 4 week follow-up. |

Risky sexual behaviors IV group: BL=15.10, 4 week FU=6.74 Control group BL=13.24, 4 week FU=9.21 F=7.56, p<.001 20 item measure included condom use; sex while intoxicated. |

| Peltzer et al., 2010 (20) | South Africa Voluntary counseling and testing centers delivered by lay counselors | 488 HIV+ adults |

Description:

Options for Health intervention, which employs motivational interviewing techniques to identify barriers to safe sex; develop strategies for overcoming barriers including alcohol use; and empower patients to use these strategies. This intervention is based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Length: 3 sessions lasting 20-30 minutes each |

Pre-post evaluations with assessments occurring at BL and 4 month FU. |

≥2 sex partners in past 3 months BL=20.7%, 4 month FU=8.2%, χ2=.32, p<.001 Never used condoms with primary partner in past 3 months BL=54.8%, 4 month FU=16.4% χ2=.23, p<.001 No condom at last sex with primary partner BL=52.6%, 4 month FU=23.6% χ2=.22, p<.001 |

| Sample: People who Abuse Drugs or Alcohol | |||||

| Chawarski et al., 2008 (27) | Malaysia Community-based outpatient treatment center. Delivered by nursing personnel. |

24 treatment seeking adults with heroin dependence |

Description: Enhanced Services (ES) was administered in addition to usual services for patients receiving buprenorphine for heroin dependence. ES included abstinence-contingent take-home doses of buprenorphine (controls received non-contingent take home doses). ES also involved weekly behavioral drug and risk reduction counseling (BDRC), including behavioral contracts aimed at improving treatment adherence, lifestyle changes, and cessation of drug-related and sexual risk behaviors. Length: Weekly 45–60 minutes sessions for 12 weeks |

RCT. All participants received medication management with buprenorphine. They were then randomly assigned to the study intervention or to a usual services control condition. Assessments at BL and at treatment end. |

Reductions in HIV risk behaviors from BL to post-treatment IV=26% reduction Control=17% reduction No test stat reported, ns |

| Chawarski et al., 2011 (28) | China Methadone maintenance treatment clinics. Delivered by nursing personnel. |

37 treatment seeking adults with heroin dependence |

Description: Behavioral Drug and HIV Risk Reduction Counseling (BDRC), a CBT-based drug counseling approach based on social learning theory aimed at engagement in activities that are incompatible with drug use. Education about heroin addiction and methadone maintenance is provided. Includes short term behavioral contracts aimed at improving treatment adherence, lifestyle changes, and cessation of drug-related and sexual risk behaviors. Length: Weekly 45–60 minutes sessions for 6 months |

RCT. All participants received methadone maintenance. They were then randomly assigned to the study intervention or to a usual services control condition. Assessments at BL and at 3- and 6- month FU. |

Reductions in self-reported HIV risk behaviors from BL to post-treatment IV group reduction > Control group reduction, F=7.17, p<.01 |

| Chen et al., 2005 (26) | China A women’s federation organization, trained prevention workers (office or home based on client preference) |

100 adult female drug users (88% injection drug users) |

Description: Non-Governmental Organization-Based Relational Intervention Model (NGO-RIM). Places Western-oriented health education and voluntary counseling and testing models in the context of Chinese ethics. Session 1 focused on education on HIV/AIDS transmission and prevention. Session 2 focused on identifying ways to overcome barriers to safe drug use and safe sex. Length: 2 sessions (45–60 minutes); 1–1.5 months apart |

Pre-post design. Assessments took place at BL and at 6-month FU. |

Condom Use: BL: 77% never use, 18% occasionally use, 2% often use, 1% use every time. 3 month FU: 45.7% never use, 30.4% occasionally use, 16.3% often use, 7.6% use every time. Standard Marginal Homogeneity test=6.89, p<.01. |

| Kalichman et al., 2008 (15) | South Africa Community-based intervention. Delivered by trained group facilitators who had minimal prior counseling experience. |

117 male and 236 female adults recruited from informal drinking establishment s (i.e., shebeens) and who reported drinking in the past month |

Description: A group-based risk reduction intervention based on an adapted version of a social cognitive model of health behavior change. Components included HIV/AIDs education focused on transmission, misconceptions/myths, local prevalence, and testing; motivational interviewing techniques aimed at both HIV risk behaviors and alcohol use; and behavioral self-management and sexual communication skill building exercises (including identification and management of triggers, role plays, and condom use demonstrations). Length: One 3 hour group session |

RCT. Random assignment of participants to either the intervention or control group, which consisted of a single 1-hour HIV/alcohol education intervention. Assessments at BL and 3- and 6-month FU. |

Instances of unprotected intercourse in past month At 6 month FU: Lighter drinking group: IV=1.2, C=3.4 Heavier drinking group: IV=2.4, C=2.0 No main effect for condition Condition X drinking interaction, F=4.1, p<.05 More effective for light drinking group Consistent condom use At 6 month FU: Lighter drinking group: IV=60%, C=56% Heavier drinking group: IV=42%, C=47% No main effect for condition or significant interaction 2+ partners At 6 month FU: Lighter drinking group: IV=8%, C=15% Heavier drinking group: IV=14%, C=14% No main effect for condition or significant interaction |

| Samet et al., 2008 (29) | Russia Inpatient substance abuse treatment facilities. Delivered by psychiatrists and psychologists trained in HIV and addictions. |

181 adults with drug and/or alcohol dependence who reported unprotected sex in the past 6 months |

Description:

Partnership to Reduce the Epidemic Via Engagement in Narcology Treatment (PREVENT) program. Program included an emphasis on basic HIV prevention knowledge; skill building related to HIV-related risk reduction for sexual and injection drug use behaviors; discussion of personal risk and creation of a behavioral change plan; promotion of safe sex through condom skills and sexual negotiation; HIV testing and review of results. Length: Two sessions lasting 30–60 minutes. Booster sessions occurred monthly for 3 months after hospital discharge. |

RCT. Control group received standard addiction treatment. Assessments occurred at BL and at 3- and 6- month FU |

% of sex acts that were protected, past 3 months 6 month FU Median difference between IV and Control groups=22.8%, p=.07 IV group reported was higher Condom use for all sexual episodes, past 3 months 6 month FU Rates not reported Adjusted OR=1.5, ns Any condom use, past 3 months 6 month FU Rates not reported Adjusted OR=3.7, p<.01 IV group was higher |

| van Griensven et al., 2004 (30) | Thailand Drug treatment clinics. Information about counselors not reported. |

2545 intravenous drug users |

Description: Educational and risk-behavior counseling based on a client-centered model (i.e., direct, personalized, and interactive). Male condoms and bleach to clean injection equipment were demonstrated and distributed free of charge. Length: 4 sessions (at BL and at 1-, 6-, and 12-month FU) |

Part of a larger RCT of a preventive HIV vaccine. All participants received behavioral counseling and were assessed on behavioral outcomes at each time point. Assessments at BL and 6- and 12-month FU. |

Always used condoms (for those with a live-in partner) BL:7.4%, 12 month FU:9.8%, Test stat not report, ns Always used condoms (for those with casual partners) BL: 46%, 12 month FU: 55%, Test stat not reported, p<.001 Had sex with 1 or more casual partners BL:13.7%, 12 month FU:10.5% Test stat not reported, p<.001 |

| Sample: Serodiscordant Couples | |||||

| Jones et al., 2005 (31) | Zambia A hospital-based Voluntary Counseling and Testing Center. Delivered by registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and other trained healthcare staff |

180 sexually active HIV positive adult women and 152 of their male partners |

Description: Group intervention based on theory of reasoned action and planned behavior as predictors of sexual barrier use. Groups were gender concordant (males or females) and focused on CBT skills to prevent HIV/STD transmission, sexual negotiation, conflict resolution and an experiential program to increase the use of sexual barriers. Distribution of condoms and vaginal lubricant. Length: All women attended 4 group sessions. Men were randomly assigned to attend either 1 or 4 group sessions. No information was provided on the length of the sessions. |

Females received the 4 session intervention; male partners were randomized to either a high intensity (4 sessions) or low intensity (1 session) intervention. No control group. Assessments at BL and 6- and 12-month FU. |

Protected sex At 12 month FU, females showed significant increases in protected sex compared to BL, t=−3.20, p<.01. Males showed the same pattern, t=−2.21, p<.05. |

| Jones et al., 2009 (32) | Zambia A hospital-based Voluntary Counseling and Testing Center. Delivered by registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and other trained healthcare staff |

392 HIV-sero-concordant (positive) and sero-discordant sexually active adult couples |

Description: Group intervention based on the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior as predictors of sexual barrier use. Groups were gender concordant (males or females) and focused on cognitive behavioral skills training to prevent HIV/STD transmission, sexual negotiation, conflict resolution as well as an experiential program to increase the use of sexual barriers. Participants were provided with male and female condoms and vaginal lubricant. Length: All women attended three 2-hour group sessions. Men were randomly assigned to attend either one or three 2-hour group sessions. |

All female participants received the 3 session intervention; their male partners were randomized to either a high intensity (3 sessions) or low intensity (1 session) intervention. No control group. Individual assessments at BL and 6- and 12-month FU. |

Male condom use Consistent use increased from BL to 12 month FU across both conditions. Males: t=16.78, p<.001; Females: t=−14.89, p<.002. Protected sex Increased among males from 76% and 71% at BL in single and multiple session groups, respectively, to 94% and 88%. Increased among females from 77% and 73% at BL in single and multiple session groups, respectively, to 94% and 88%. No test stat provided. |

| Kamenga et al., 1991 (33) | Zaire HIV counseling center. Delivered by a male physician and female nurse. Home sessions if couple was unable to make it to the clinic. |

149 married couples with discordant HIV status |

Description: Couples counseling aimed at preventing infection of HIV negative partner in discordant couples. Intervention consistent of HIV status disclosure, counseling on condom use, STDs, and HIV infection, condom distribution, monitoring of safe and unsafe sex incidents, and medical care. Length: Monthly sessions and repeat physical exams every 6 months. Average length of follow up was 15 months. |

Prospective cohort study with no control group. Assessments at BL and 6- and 18-month FU. |

HIV-1 seroconversion 6 couples (4%) became HIV concordant during follow-up. Condom use with partner <5% had ever used condoms at BL, 70.7% used condoms 100% of the time 1 month after disclosure. This was sustained at 18 months. No significance testing. |

| Sample: Key HIV-related Populations | |||||

| Jackson et al., 1997 (40) | Kenya On-site clinics in depots of 6 large trucking companies. Mobile health team of physicians, nurses, and health educators |

Cohort study of 556 HIV-sero-negative men working at a trucking company. |

Description: The risk reduction intervention consisted of the following components: education about HIV/STD transmission, promotion of condom use and a reduction in sexual partners, free condoms, condom demonstration on a penile model, and HIV/STD testing. Length: Meetings every 3 months (or as a participant’s work schedule allowed) for a 12 month period. 65% of men returned for at least one follow-up appointment, and the mean number of follow-up visits was 2.9 (range 1–8). |

Time series with non-probability sampling. Assessments at BL and every 3 months for 12 months. |

Consistent condom use during extramarital sex 0–3 month: 34% 4–6 month: 27% 7–9 month: 30% 10–12 month: 38% 13–15 month: 18% 16+month: 29% ns (GEE) Extramarital sex 0–3 month: 50% 4–6 month: 50% 7–9 month: 45% 10–12 month: 46% 13–15 month: 39% 16+month: 40% p<.001 (GEE) STD Incidence (reported or observed) 0–3 month: 85% 4–6 month: 74.1% 7–9 month: 54.2% 10–12 month: 31.9% 13–15 month: 19.6% 16+month: 23.5% p<.0001 (GEE) |

| Kalichman et al., 2007 (4) | South Africa STI Clinic Delivered by bachelors level intervention counselors |

143 patients receiving services at an STI clinic and currently using alcohol |

Description: A behavioral skills building HIV and alcohol risk reduction counseling intervention based on the social cognitive model of health behavior change. Components included: provision of education about HIV transmission and risk behaviors, local prevalence rates, common misconceptions/myths, and testing; motivational counseling for HIV risk behaviors and alcohol use; and behavioral self-management and sexual communication skill building exercises (including identification and management of triggers, role plays, and condom use demonstrations). Length: One 60 minute session |

RCT. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental condition or a control condition, which consisted of a 20 minute education/information session. Assessments at BL and 3- and 6-month FU. |

Condom use, last sex At 6 month FU: IV=96%, Control=82%, OR=5.3, ns* Number of sex partners At 6 month FU: IV=1.6, Control=2.5 F=0.3, ns* Unprotected vaginal intercourse occasions At 6 month FU: IV=1.3, Control=2.1 F=5.6, p<.05* Unprotected anal intercourse occasions At 6 month FU: IV=0.1, Control=1.3 F=0.1, ns* Percent condom use At 6 month FU: IV=87.8%, Control=76.4% F=5.7, p<.05* *controlling for BL values and demographics |

| Kaul et al., 2002 (34) | Kenya HIV clinic Trained counselors and female sex worker peers. |

335 female sex workers |

Description: Peer and clinic-based risk reduction counseling, free condoms, STI treatment, counseling on consistent condom use, testing for HIV and other STIs. Length: Two standardized 1-hour risk reduction counseling sessions with subsequent sessions provided based on perceived needs of the client. |

Part of a larger medication trial. Pre-post study with assessments at BL and every 3 months with an average follow-up of 489 days. |

100% condom use BL: 17%, FU: 57.7% (most recent FU available) No test statistic, p<.001. Number of clients BL: 16.33, FU: 5.03 (most recent FU available) No test statistic, p<.001. |

| Levine et al., 1998 (19) | Bolivia STD Clinic Teams of trained outreach professionals and psychologists |

508 female sex workers |

Description: Outreach teams visited brothels in two-person teams and met with them in group sessions and informally. They covered topics of STD and HIV symptoms and transmission; the importance of regular clinic attendance; condom use; negotiation of condom use with clients; and improving self-esteem and empowerment. There were also clinic-based group and individual sessions provided by psychologists on the same topics. This program was implemented in conjunction with other STD prevention programming (e.g., STD testing and treatment, other medical services, availability of low-cost condoms). Length: Variable. No descriptive data provided on number of sessions. |

Serial cross-sectional design with open cohort. Observations at every comprehensive examination from 1992 to 1995. |

Condom Use 1992: 36.3% of FSW 1995: 72.5% of FSW No test statistic, p<.001 Gonorrhea 1992: 25.8% of FSW 1995: 9.9% of FSW No test statistic, p<.001 Syphilis 1992: 14.9% of FSW 1995: 8.7% of FSW No test statistic, p=.02 Genital Ulcers 1992: 5.7% of FSW 1995: 1.3% of FSW No test statistic, p=.006 Tichomaniasis 1992: 17.0% of FSW 1995: 16.3% of FSW ns Chlamydia 1992: 17.4% of FSW 1994: 10.9% of FSW ns |

| Ngugi et al., 2007 (35) | Kenya HIV clinics. Delivered by peers and by clinic-based personnel (not described). |

172 HIV uninfected female sex workers |

Description: Individual clinic-based sexual risk reduction counseling based on perceived needs and self-reported sexual behaviors of participants. In addition, sex worker community meetings led by a female sex worker peer were provided with discussions focused on risk reduction and negotiation of condom use with casual and regular clients. Finally, a wider meeting of female sex workers was held to address risk reduction issues pertaining to the sex worker community. Length: Individual services were 2 hour long sessions. Community meetings were held quarterly and wider meetings were held every 6 months over 4 years. |

Participants were part of a larger RCT for an STD medication (azithromycin). All participants received behavioral counseling. Assessments at BL and over 1 year following study termination. |

Mean number of regular clients BL=0.9, FU=1.3, p<.001 (Wilcoxon signed rank test) Condom use with regular clients BL:1.1 on 5 pt scale FU: 3.5 on 5 pt scale p<.001 (Wilcoxon signed rank test) Condom use scale ranges from 0 (no use) to 5 (100% use) STI prevalence Chlamydia, BL=7.6%, FU=2.4%, p<.05 Gonorrhea, BL=8.1%, FU=4.2%, p=.10 Trichomonas, BL=13.5%, FU=0%, p<.001 Wilcoxon signed rank tests HIV incidence During original clinical trial: 3.7/100 person yrs From study end to follow-up: 1.6/100 person years 2-sample comparison of Poisson rates, ns |

| Patterson et al., 2008 (17) | Mexico Women’s health clinic. Trained counselors. |

924 female sex workers without known HIV infection and who had unprotected sex with a client in the past 2 months |

Description:

Mujer Segura (Healthy Women) intervention. Brief behavioral intervention to enhance condom use negotiation. Uses motivational interviewing to target safe sex, barriers to condom use, condom use negotiation, and enhancement of social support. Techniques include role plays, a decisional balance approach, development of a plan of action, and identification and problem solving of barriers. Length: One 35-minute session |

RCT with a time equivalent didactic control group. Assessed at BL and 6 month FU. |

HIV Incidence (6 month FU) IV=0%, Control=1.1%, ns STI Incidence (6 month FU) Syphilis IV=2.1%, Control=4.2%, ns Gonorrhea IV=3.4%, Control=4.3%, ns Chlamydia IV=5.3%, Control=5.6%, ns Any STI IV= 7.7%, Control=12.8%, p<.05 Condom Use BL: IV=56.3%, Control=58.0% 6 month FU: IV=83.7%, Control=75.5% F=9.78, p<.01 |

| Simbayi et al., 2004 (38) | South Africa STI Clinics. Delivered by trained counselors. |

228 STI clinic patients seen for repeat STI |

Description: Intervention based on the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills model of health behavior change. Includes 3 components: 1) informational (e.g., HIV facts, local prevalence, HIV testing); 2) motivational (using motivational interviewing); and 3) risk reduction (behavioral self-management, sexual communication skills, functional analysis of risk behaviors, identification and management of triggers for high-risk situations, role plays, condom demonstrations). Length: One 60 minute session |

RCT. Control group received only the first component (informational) delivered in a 20-minute session. Assessments occurred at BL and 1- and 3- month FU. |

Number of sex partners 3 month FU IV: BL=2.3, FU=2.2 Control: BL=2.2, FU=1.4 F=2.4, ns % of sex unprotected 3 mo FU IV: BL=31.6%, FU=13.3% C group: BL=40.9%, FU=23.6% F=5.7, p<.01 |

| Wechsberg et al., 2006 (36) | South Africa Delivered in communities by trained multi-lingual field staff. |

93 women reporting recent substance use and sex trading |

Description: The Women-Focused intervention, based on principles of social cognitive theory, gender theory, and empowerment. Includes a personalized assessment of drug and sexual risks that then inform specific risk reduction goals. In addition, women learn condom negotiation, violence prevention strategies, communication techniques, and how to seek community resources. The intervention was culturally adapted to address attitudes towards women and beliefs/values about sex. HIV education was provided to dispel HIV/AIDs myths and increase factual knowledge. Role plays included proper male and female condom use and verbal assertiveness. Length: Two (~) 1 hour sessions |

RCT. Control group received an adapted version of the revised National Institute of Drug Abuse Standard Intervention (same length as the Women-Focused intervention and included educational and skill building in regards to sexual risk, male and female condom demonstration, and information about referral resources). Assessments at BL and 1 month FU. |

Condoms always used with boyfriends, past month IV: BL=23%, 1 month FU=33% Control: BL=36%, 1 month FU=36% Test stat not reported, ns Condoms always used with clients, past month IV: BL=94%, 1 month FU=97% Control: BL=92%, 1 month FU=82% Test stat not reported, ns Self-reported STI symptoms At 1 month FU (BL not reported) IV =.64, Control=1.07 ES[d]=−.43, p not reported |

| Wechsberg et al., 2010 (37) | South Africa Treatment setting and information on counselors not reported. |

583 women reporting recent substance use and either sex trading or recent unprotected sex |

Description: Women-Focused intervention, based on principles of gender and empowerment theory. Personalized assessment of drug and sexual risk to inform goals. Covers condom negotiation, violence prevention, communication, and community resources. Culturally adapted to address attitudes towards women and sex. HIV education to dispel myths. Role play for condom use and verbal assertiveness. HIV testing was offered. Length: Two (~) 1 hour sessions |

RCT. Control was the same length. Included education, skill building, condom demonstration, and referral resources. HIV testing was offered. Assessments at BL and 3 and 6 month FU. |

Condom use at last sex act At 6 month FU IV: 52% Control: 37% No test stat reported, p<.05 |

| Zhang et al., 2010 (41) | China Information on setting and counselors not provided. |

218 men who have sex with men (MSM) |

Description: A peer-driven behavioral group intervention based on the AIDS Risk Reduction Model. IV groups consisted of a “seed” and his referral chain made up of his peers. Sessions included role playing, games, group discussions, brainstorming, and competitions to test HIV knowledge. Individual’s high-risk behaviors were assessed and addressed through individualized plans and problem solving of potential barriers to these plans. Role plays included condom demonstrations and condom negotiation with partners. Length: Four 1.5 hour sessions |

Pre-post design without a control group. Assessments at BL and 3 month FU. |

Condom use during last 3 anal sex instances with men BL=55.3%, 3 month FU=65.2%, p<.01 No condom use in last sex with regular partner BL=45.3%, 3 month FU=31.2%, p<.01 2 or more male partners, past 2 months BL=38.2%, 3 month FU=41.2%, ns |

| Sample: Individuals with Moderate to Low Risk for HIV | |||||

| Kalichman et al., 2009 (16) | South Africa Group-based intervention delivered by experienced 2 facilitators (1 male, 1 female). Delivery setting not reported. |

475 men |

Description: Group-based gender violence and HIV-prevention intervention grounded in behavioral theory. Skills included condom use, identifying and problem solving antecedents to violence against women, communication skills, and advocating for risk reduction behavior changes in other men. Techniques included didactics, role plays, viewing of scenes from films and TV, goal setting, and problem solving. Length: 5 sessions |

Quasi-experimental. Two communities randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Control intervention was the 3-hour group session from Kalichman et al. (2008). Assessments at BL and 1-, 3-and 6-month FU. |

% intercourse condom protected At 6 month FU: IV=74.1% Control=72.5%, F=0.3, ns Number of partners, past month At 6 month FU: IV=1.6 Control=1.4, F=4.9, p=.05 Controlling for age, BL scores. |

| Wang et al., 2009 (18) | China County hospitals delivered by physicians |

Independent samples of 242 (BL) and 287 (6 mo FU) patients seeking outpatient services. 2–3 patients from each MD’s caseload |

Description:

Ai Shi Zi (“AIDs Plus”), an intervention to train physicians on HIV/STI prevention and treatment. Objectives include four content areas: 1) epidemiology and pathogenesis; 2) treatment; 3) STI management; and 4) behavioral risk reduction counseling, including active listening, empathy, and sensitivity. Length: Not reported. |

Pre-post design with independent patient cohorts. 69 physicians were trained during a and then returned to their clinics to deliver the intervention. Assessments prior to the physicians entering the program and at 6 mo FU. |

% never used condoms, past 6 months BL=65% 6 month FU=52.4% Test stat not reported, p<.01 |

| Xu et al., 2002 (5) | Thailand Family planning clinics and a postpartum ward. Information on counselors not reported. |

779 seronegative women |

Description: Counseling was individualized based on woman’s risk profile. Recommended condom use if husband’s HIV status was unknown and HIV testing of husbands. Condoms were demonstrated and distributed. Reimbursement for husband’s HIV testing was offered. Length: Three 20–45 minutes (at BL, 6 mo, and 12 mo FU) |

Pre-post design without a control group. Assessments at BL and at 6- and 12-mo FU. |

HIV seroconversion 1 woman seroconverted by 12 month FU Incidence=0.14/100 person-years Consistent condom use BL=2%, 12 month FU=5%, No significance testing |

IV=intervention group; BL=baseline; FU=follow-up; GEE = Generalized Estimating Equations; STI=Sexually Transmitted Infections; OR=odds ratio; FSW=female sex worker; RCT=randomized controlled trial; ES=effect size. When data from multiple follow-ups were reported in the original papers, the longest follow-up was included in the review.

There was substantial variability in the number of sessions, which ranged from 1 to over 30. The most common number of sessions was 2 (n=7), 3 (n=6), 4 (n=5), and 1 (n=4). Remaining studies reported 5 or more sessions, with 3 studies reporting 10 or more sessions. One study did not report the number of sessions. There was also variability in treatment settings, with 5 studies taking place in HIV/STI treatment clinics, 9 in or associated with HIV testing and counseling centers (but provided independent of the HIV testing itself), 3 in community settings, 3 in substance abuse treatment facilities, 3 in general medical settings, 2 in antenatal clinics, and 1 providing treatment in either the office of a nongovernmental organization or in participants’ homes. One study had two settings, an HIV testing and counseling center and an HIV/STI treatment center. Three did not describe the setting.

An assessment of rigor across studies showed strengths and weaknesses (Table 2). Nineteen studies had control groups; eleven did not. All but two (18, 19) followed the same individuals over time. Eight were unable to retain at least 80% of their sample; three did not report follow-up rates. One reported baseline differences between intervention and control groups on primary outcomes; six did not report baseline rates of primary outcomes. Given this substantial variability in rigor, studies with stronger designs are highlighted in the discussion of results.

Table 2.

Assessment of Study Rigor

| Study | Cohort | Control or comparison group | Pre/post intervention data | Random assignment of participants to intervention | Random selection of participants for assessment | Follow-up rate of 80% or more | Comparison groups equivalent on socio-demographics | Comparison groups equivalent at baseline on outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chawarski et al., 2008 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Chawarski et al., 2011 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes |

| Chen et al., 2005 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | yes | NA | NA |

| Cornman et al., 2008 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Futterman et al., 2010 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | NR |

| Jackson et al., 1997 | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | NA | NA |

| Jones et al., 2004 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | NR | yes | yes |

| Jones et al., 2005 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | NR | NR | no |

| Jones et al., 2006 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | NR | yes | yes |

| Jones et al., 2009 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | NR | yes | yes |

| Kalichman et al., 2007 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes |

| Kalichman et al., 2008 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Kalichman et al, 2009 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | NR |

| Kamenga, 1991 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | yes | NA | NA |

| Kaul et al., 2002 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | yes | NA | NA |

| Levine et al., 1998 | no | no | yes | NA | no | NA | NA | NA |

| MacNeil et al., 1999 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Ngugi et al., 2007 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | no | NA | NA |

| Olley 2006 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | NR | NR |

| Patterson et al., 2008 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | no |

| Peltzer et al., 2010 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | no | NA | NA |

| Piwoz et al. 2005 | yes | yes | no | no | no | NR | no | NR |

| Samet et al., 2008 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | yes |

| Simbayi et al., 2004 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes1 | yes | yes |

| Solomon et al., 2006 | yes | no | yes | N/A | no | yes | NA | NA |

| van Griensven et al., 2004 | yes | no | yes | no | no | yes | NA | NA |

| Wang et al., 2009 | no | no | yes | NA | no | NA | no | yes |

| Wechsberg et al., 2006 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | NR | NR |

| Wechsberg et al., 2010 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | NR | NR |

| Xu et al., 2002 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | yes | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al., 2010 | yes | no | yes | NA | no | no | NA | NA |

The follow-up rate at 1-month was 80%, and the follow-up rate at 3-months was 79%.

Outcome measures were equivalent on all but one measure.

NA=Not applicable; NR=Not reported.

Interventions were adapted for a wide range of populations: 1) PLHIV; 2) people who use drugs/alcohol; 3) HIV serodiscordant couples; 4) key populations for HIV prevention (female sex workers, men working at trucking companies, individuals seeking STI treatment, men who have sex with men); and 5) individuals at low to moderate risk (i.e., community samples, individuals seeking general health care, women seeking family planning or receiving postpartum care). To examine differences in BC strategies by group, we present results separated by population below.

People Living with HIV (PLHIV)

Seven studies examined BC for PLHIV. The goals of these interventions were to reduce HIV transmission to the individual’s sexual partner(s) by increasing use of condoms, chemical barriers (e.g., vaginal lubricants, microbicides), or abstinence and/or decreasing the number of sexual partners or frequency of intercourse as well as to promote mental health and well-being among PLHIV. Two used the information-motivation-behavioral skills model of HIV prevention and motivational interviewing (3, 20), two were based on the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior and utilized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques (21, 22), one used CBT (23), and the remaining two did not identify a theoretical orientation but used risk reduction (24) and psychoeducational approaches (25).

The majority of studies in this group were rigorously designed randomized controlled trial (RCTs; n = 5), whereas two used less rigorous designs. In a RCT in South Africa (3), BC delivered during routine HIV clinic visits decreased unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts among intervention participants compared to controls between baseline and 6-month follow-up (time X condition interaction, b=−2.24, p=.016). Specifically, there was a decrease from 2.64 to 0.40 in the intervention group and an increase from 2.26 to 3.85 in the control group. There was no effect on overall number of sex acts.

Two RCTs from the same research group examined BC for female PLHIV in Zambia. Jones et al. (22) provided BC in group and individual formats compared to usual services. At 6-month follow-up, group BC showed a greater increase in male condom use (χ2=7.3, p<.001) and overall practices of protected sex (χ2=9.5, p<.001) than either individual BC or usual services. The second study compared the same BC group intervention to an individually-focused control condition (21) and found no between-group differences in condom use at 12-month follow-up.

Two RCTs examined BC delivered to PLHIV in HIV counseling and testing centers as add-ons to typical services provided at these centers (i.e., in addition to typical HIV counseling sessions). The first compared BC to regular health services in Tanzania and did not find significant group differences in improvements on condom use or STI symptoms from baseline to 6-month follow-up (24). A second RCT compared 4 sessions of BC to a waitlist control in Nigeria (25). The BC group showed significantly more improvement (F=7.56, p<.001) than the control group from baseline to 1-month follow-up on a 20 item measure of risky sexual behaviors (i.e., the BC group showed a drop in score from 15.10 to 6.74 whereas the control group dropped from 13.24 to 9.21).

Two of the studies were less rigorously designed. The first, a non-randomized trial comparing group-based BC to standard care for HIV-positive pregnant women in South Africa found no effect on abstinence/consistent condom use (23). The second, also conducted in South Africa, used a pre-post design to evaluate 3-sessions of BC and, found decreases in percentages of participants: a) with multiple sexual partners (χ2=.32, p<.001), b) never using condoms with primary partners (χ2=.23, p<.001), and c) not using condoms at last sex with primary partner (χ2=.22, p<.001) (20).

Overall, evaluations of BC for PLHIV showed mixed support for its efficacy. Among studies with the strongest research designs, 2 of 5 BC interventions increased condom use or protected sex (3, 25), with one of these providing data from a relatively short-term follow-up (i.e., 4 weeks) (25). Two of the studies compared individual to group based BC and did not result in definitive conclusions about BC in general (21, 22). The other rigorously designed study failed to find significant effects on behavioral outcomes (24). In the less rigorously designed studies, the pre-post comparison found improvements in risky sexual behaviors (20) but the non-randomized trial failed to find significant effects (23).

People Who Use Drugs or Alcohol

Six studies examined BC for individuals at high-risk for HIV infection due to use or abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs. These interventions generally aimed to reduce risky sexual behaviors associated with substance use. In terms of theoretical orientation, one study utilized a relational intervention model (26), two used CBT (27, 28), one used social cognitive theory (15), and two did not identify theoretical underpinnings but used risk reduction approaches (29, 30).

Four of these studies were rigorously designed RCTs. A pilot RCT conducted in an outpatient substance use treatment clinic in Malaysia was part of a larger clinical trial for medication management of heroin dependence (27). All participants received medication management and were randomly assigned to either BC or usual services. Both groups showed reductions in HIV risk behaviors (i.e., drug-related and sexual risk) from baseline to treatment end (F=10.2, p<.05), but there were no significant group differences in percent reduction in these behaviors. A second RCT from the same researchers was conducted in a methadone maintenance clinic using the same design (28). Similar to the earlier study, both groups showed reductions in HIV risk behaviors (F=33.13, p<.001); however, the intervention group showed a greater reduction than controls (F=7.17, p<.01). An RCT conducted in an inpatient substance use treatment facility in Russia compared BC to standard addiction treatment (29). At 6-month follow-up, the BC group reported a higher (though not statistically significant) percentage of protected sex acts (median difference between intervention and control groups=22.8%, p=.07) and higher overall rates of condom use (OR=3.7, p<.01) compared to the control group, but there were no group differences in consistent condom use. Finally, a 1-session BC model with non-treatment seeking adults from informal drinking establishments in South Africa produced no significant improvements in unprotected sex, condom use, or number of partners compared to controls (15). However, there was evidence that the intervention worked for participants who identified as light drinkers compared to heavier drinkers.

The remaining two studies used pre-post designs. The first revealed increased condom use between baseline and 6-month follow-up after 2 sessions of BC (standard marginal homogeneity test=6.89, p<.01) in China (26). The second recruited a large sample (N=2545) of intravenous drug users in Thailand (30) as part of a larger RCT for a preventive HIV vaccine. All participants received BC. Participants with casual (but not live-in) partners showed increases in consistent condom use from baseline (46%) to 12-month follow-up (55%; p<.001). Further, participants reported fewer casual partners at 12-month follow-up (10.5%) than at baseline (13.7%, p<.001). These results represent statistically significant but small changes in behavior.

In sum, the majority of the RCTs for individuals abusing drugs or alcohol revealed no advantage of the BC intervention compared to usual services on measures of HIV risk behaviors (27), condom use (15), number of partners (15), or consistent condom use (29). Two studies showed decreased HIV risk behaviors (28) and increased condom use, though not an increase in the percentage of individuals practicing consistent condom use (29). Pre-post evaluations found increased condom use (26, 30) and decreased sexual partners (30); however, given the limitations inherent to these designs, it is unknown whether these effects were due solely to BC.

Serodiscordant Couples

Three studies evaluated BC to reduce HIV risk behaviors and transmission among HIV serodiscordant couples. The goals of these interventions were to decrease unprotected sex between partners through the provision of education on HIV transmission and safe sex as well as increasing sexual negotiation, HIV status disclosure, and/or safe sex practices. Two were based on the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior (31, 32), while the remaining study did not identify a theoretical orientation (33).

None of the studies were of high rigor. Two studies conducted by the same researchers examined a group intervention in Zambia. Both administered group sessions to women living with HIV and randomly assigned their male partners to either a low intensity (1 session) or high intensity (3 or 4 sessions) of group BC (31, 32). Both reported increased protected sex at 12 month follow-up. The third study examined couples-focused BC in DR Congo. A prospective cohort study (33) found that, by 18-month follow-up, 6 of the 149 discordant couples became HIV concordant, and condom use with partners increased from less than 5% at baseline to 70.7% following HIV disclosure, an improvement that was sustained at 18-month follow-up.

In sum, the study designs used in evaluations of BC for serodiscordant couples were weak. Pre-post evaluations showed small to moderate increases in protected sex (31, 32), though it is impossible to determine whether these rates were lower than they would have been without intervention.

Key Populations for HIV Prevention

Ten studies focused on key populations for HIV prevention, including six with female sex workers (17, 19, 34-37), three with adults seeking STI treatment (4, 38, 39), one with male truckers (40), and one with men who have sex with men (MSM) (41). Interventions for these populations generally sought to increase knowledge about HIV transmission, motivation to engage in safer sex to prevent infection, and behavioral risk reduction techniques. Two interventions were based on a combination of social cognitive and gender and empowerment theories (36, 37), one was based on a combination of social cognitive theory and the theory of reasoned action and utilized a motivational interviewing approach (17), and one was based solely on social cognitive theory (4). An additional intervention was based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model of behavior change and used motivational interviewing (38), while another was based on UNAIDS’ AIDS risk reduction model (41). The remaining five studies did not identify a theoretical orientation (19, 34, 35, 39, 40).

Three of the studies recruiting female sex worker were RCTs. The first found no differences between participants receiving 1 session of BC and those in a time-equivalent control group on incidence of HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia, but did find an effect for overall STI incidence (p<.05), such that 12.8% of the control group but only 7.7% of the intervention group tested positive for an STI at 6-month follow-up (13). There was also a greater increase in condom use for the BC group than controls from baseline to 6-month follow-up (F=9.78, p<.01). The other two RCTs were from the same researchers and compared a 2-session intervention to usual services in South Africa. Wechsberg et al. (36) did not find significant effects on consistent condom use with boyfriends or clients in the past month but did find an effect for self-reported STI symptoms at 1-month follow-up (d=.43, p value not reported). Wechsberg et al. (37) found a significant effect on condom use during last sex at the 6-month follow-up (p<.05).

Two of the studies with female sex workers were part of larger drug trials in which all participants received BC. The first found pre-post changes in rates of 100% condom use (p<.001) and number of clients (p<.001) (34). The second was part of a medication trial for STI prevention and also found significant pre-post changes, specifically an increase in mean number of regular clients (p<.001), increased condom use with regular clients (p<.001) and increased prevalence of chlamydia (p<.05) and trichomonas (p<.001). There was no significant change in gonorrhea prevalence or HIV incidence (35).

The final study with female sex workers used a serial cross-sectional design to determine whether implementation of a BC intervention in conjunction with improved HIV/STD testing services and outreach could decrease sexual risk taking behaviors in a population of female sex workers over a four year period (19). The study found significant increases in condom use (p<.001) and significant decreases in the prevalence of gonorrhea (p<.001), syphilis (p<.05), and genital ulcers (p<.01) but no significant decrease in Chlamydia or trichomaniasis between 1992 and 1995.

There were three studies of BC for adults seeking STI treatment. Two RCTs from the same researchers evaluated a one-session BC intervention in South Africa. Simbayi et al. (38) found no significant differences between BC and control groups on number of partners at 3-month follow-up, but participants in the intervention group had a significantly lower percentage of unprotected sex acts compared to controls. Kalichman et al. (4) also reported no effect on condom use at last intercourse, number of partners, or unprotected anal intercourse occasions, but the BC group reported fewer instances of unprotected vaginal intercourse (mean of 1.3 instances in the intervention group, 2.1 in the control group, p<.05) and higher percentages of condom use (87.8% of the time in the intervention group, 76.4% of time in the control group) compared to controls at 6-month follow-up. In addition, a pre-post study examined a 3-session intervention for individuals seeking STI treatment and found significant reductions in mean number of partners (p<.001) but no effect on condom use or frequency of vaginal sex (39).

Finally, Jackson et al. (35) used a time series cohort design to examine a 12-month BC intervention for truckers in Kenya and found reductions in extramarital sex (p<.001) and STI incidence (observed or reported; p<.001) but no significant change in condom use during extramarital sex. Zhang et al. (41) used a pre-post design to examine a 4-session peer-driven group intervention for MSM, finding increased condom use during anal sex (p<.01); decreased rates of unprotected sex (p<.01) but no effect on number of partners.

Overall, rigorously designed studies of preventive BC interventions for individuals at high-risk for HIV infection failed to find effects on condom use or protected sex (4, 36), HIV or STI incidence (42), or sexual partners (38). There were also some positive findings. One study found significant decreases in unprotected vaginal intercourse (though not unprotected anal intercourse) (4), one found a significant decrease in the percentage of unprotected sex acts (38), one reported decreased incidence of overall STIs (though not any individual STI) (17), one reported significant decreases in self-reported STIs (36), and one found significant increases in condom use (37). Each of the significant findings was modest in size. Similar to the other groups, many of the pre-post evaluations found some improvements, including decreased extramarital sex (40), STI incidence or prevalence (19, 35, 40), and sexual partners (34, 35, 39), and increased condom use (19, 34, 35, 41), whereas a few did not find pre-post decreases in number of partners (39, 41).

Individuals with Moderate to Low HIV Risk

The remaining studies examined BC with relatively low-risk community samples. These interventions took a broad-based primary prevention approach to decreasing the spread of HIV, typically with a goal of reaching larger communities of people living in countries with high HIV prevalence rates. One of the interventions was based on social cognitive theory (16), while the other two did not identify a theoretical orientation (5, 18).

One of the studies used a community randomized design (16), and the other two used pre-post designs (5, 18). The randomized design compared a South African community randomly assigned to receive a group-based gender violence and HIV prevention BC intervention to a control community (16). At 6-month follow-up, participants in the BC community reported fewer sex partners than controls (F=4.9, p=.05) but there were no effects on condom use. A study using a pre-post design recruited independent patient cohorts before and after training Chinese hospital-based physicians to deliver BC (18). At 6-month follow-up, a higher percentage of patients (37.3%) reported ever being tested for HIV compared to baseline, and a lower percentage reported never using condoms in the past 6 months compared to baseline (both p’s <.05). A pre-post design was used to evaluate a 3-session BC intervention with seronegative women in Thailand (5). At 12-month follow-up, there was a 3% increase in consistent condom use (from 2% at baseline to 5% at 12 month follow-up, no significance testing reported).

In sum, only three studies examined BC interventions designed for individuals at moderate to low risk for HIV, and two of the studies did not provide a rigorous evaluation of the interventions (5, 18). They found decreased partners (16) and increased condom use (18) but failed to find an impact on consistent condom use (5, 16).

Discussion

We identified 30 studies that examined the effects of BC for HIV prevention on sexual risk behaviors and biological outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. There was substantial diversity across studies in intervention length, theoretical orientation, and delivery setting. BC was adapted for use with a variety of populations, including PLHIV, people who use drugs/alcohol, HIV serodiscordant couples, key populations for HIV prevention, and individuals at low to moderate HIV risk. Importantly, there was also substantial variability in study rigor, with many more RCTs conducted since UNAIDS’ previous review (42), allowing for more decisive conclusions about BC’s efficacy.

Overall, the results call into question the effectiveness of BC for HIV risk reduction when evaluated with rigorously designed studies. This was the case for the BC interventions for PLHIV, people who use drugs or alcohol, and key populations. Although results of pre-post designs often showed positive effects of BC for these three groups, the RCTs largely showed a lack of or mixed findings on the sexual behavior outcomes most closely associated with HIV infection risk. Thus, based on the studies reviewed, the reliance on BC strategies alone for these groups is insufficient for reducing sexual transmission risk. This is in contrast to an earlier review that found that HIV counseling and testing interventions (not BC per se) was effective as a secondary prevention strategy for PLHIV but not effective for uninfected participants (9).

The lack of effectiveness of BC for PLHIV is consistent with studies showing that a comprehensive approach covering a range of intervention modalities is necessary for prevention in this group (43). Though this review indicates that BC alone is likely not effective for PLHIV, a positive prevention approach focused on positive health, dignity, and transmission prevention is recommended and should include both biomedical and behavioral interventions, one of which may be BC. Similarly, there is little evidence that BC is effective for reducing behavioral risk for key populations (e.g., female sex workers, MSM). Thus, it is likely that these groups also require a more comprehensive approach to prevention. Specific to studies of BC for people who use drugs or alcohol, it should be noted that some of these BC interventions also aimed to reduce risk behaviors specifically related to substance abuse (e.g., sharing needles, engaging in sex while intoxicated). A review of these outcomes is beyond the scope of this review but it is possible that BC is more effective in reducing substance use related behaviors than it is for sexual risk behaviors.

There was variability in the quality of studies across target groups, precluding strong conclusions about the efficacy of BC for some groups. Specifically, the studies of BC for both HIV serodiscordant couples and individuals with moderate to low risk for HIV were few in number and were not rigorously designed. Thus, it is not possible to make definitive conclusions about the use of BC for these groups, and additional research is warranted. It should be noted, however, that serodiscordant couples may represent a unique population, as they tend to increase their use of condoms substantially upon learning their serostatus (13, 11). Thus, testing itself is a powerful intervention for this group, and the later addition of BC focused on sexual risk reduction may not have incremental value. However, as prevention options for serodiscordant are expanding now (e.g., treatment as prevention, PrEP) are becoming more widely available, BC could be a potentially useful tool in helping couples to explore options and identify prevention methods that works for them. In the case of the moderate to low risk group, there is likely a floor effect in these studies, as these groups often already display low levels of risky sexual behaviors at baseline. The potentially poor cost-benefit ratio of intervening with this population rather than targeting PLHIV or high-risk groups detracts from the viability of this approach. This is similar to conclusions made about the utility of BC for low-risk groups in the U.S. (6).

Another important limitation is the inability to conduct a meta-analysis, which was due to two aspects of the studies reviewed. First, only four of the included studies reported the necessary statistics to calculate effect sizes. This speaks to the need for a more standardized outcome metrics for this field. Second, there was significant heterogeneity in study design, target populations, and intervention characteristics that precluded the use of meta-analysis. We chose to summarize the findings within each target population, as these groupings have practical importance for program implementation decisions. We also highlighted findings from more rigorously designed studies. Despite these efforts, the lack of meta-analytic results limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions.

One important qualification to these findings is that the control conditions utilized in the large majority of the RCTs were “active” conditions of similar length and intensity as the BC interventions. Further, some of the control groups were provided with HIV risk reduction strategies, such as testing, condom distribution, and HIV education, also offered in the BC interventions. This may have diminished the differences found between groups and, thus, the perceived effectiveness of BC. Another important qualification is that, although risky sexual behavior and biological indicators were the focus of this review, many of the BC studies focused on additional outcomes, including HIV knowledge and other HIV transmission risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, breastfeeding) and protective factors (e.g., partner HIV testing, adherence to medications, mental health and adjustment) that were beyond the scope of this paper. Thus, conclusions about the potential usefulness of BC for outcomes other than the ones reviewed here cannot be made. Finally, many of the reported behavioral outcomes were assessed using self-report measures only, which have been subject to demand characteristics of the study.

Conclusion

Across target groups, RCTs generally revealed either moderate or little benefit from BC compared to usual services. Less rigorous designs showed that risky sexual behaviors and biological indicators improved following BC interventions; however, without controls, it is unclear whether BC itself had an impact greater than usual services. Therefore, the overriding conclusion based on the studies reviewed is that standalone BC interventions add little to the effectiveness of HIV prevention services already available in many communities for PLHIV, people who abuse drugs/alcohol, and people at high-risk for HIV transmission. Additional research is needed to make conclusions about the efficacy of BC for serodiscordant couples and individuals at low to moderate risk for HIV.

Implications

Results of this review do not support the use of BC as a sole HIV prevention strategy in low- to middle-income countries, although as suggested above, this conclusion is somewhat limited by the heterogeneity and quality of the reviewed studies, and more research is needed for a definitive recommendation. These findings provide support for the idea that there is no single stand-alone intervention that will be effective at reducing population risk for HIV infection. As a whole, the field is moving towards combination HIV prevention, defined by USAID as an approach that “relies on the evidence-informed, strategic, simultaneous use of complementary behavioral, biomedical and structural prevention strategies.”(44) Effective prevention will need to target risk factors at individual, dyadic, community, and societal level and will need to be tailored to meet the needs of specific groups and contexts. Countries and settings need to identify the risk factors for HIV in their population and strategically choose multimodal multilevel preventive interventions to address these specific needs. Though the conclusions from this review do not support the efficacy of BC as a stand-alone intervention, it is still possible that it could be an effective approach when used to target specific HIV risk factors in the context of larger combination HIV prevention programs. Research on the combinations of such interventions to meet the epidemiological needs of specific populations is still in its infancy (45), but future studies may consider BC as one potential individual-level intervention in a larger multi-level program that includes relational, community and structural level interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health, grant number 1R01MH090173 and The Horizons Program. The Horizons Program was funded by The US Agency for International Development under the terms of HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The first author is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant numbers K12DA031794 and K23DA034879. The study authors thank Alicen Spaulding, Kiesha McCurtis, Hieu Pham, Eugenia Pyntikova, Jewel Gausman, Alexandria Smith, Erica Layer, Jeremy Lapedis, Erica Koegler, Lindsay Litwin, Canada Parrish, Taylor Whitten, Esther Lei, Swathi Manchikanti, Jenny Tighe, Isabelle Feldhaus, April Monroe, Sarah Robbins, Salwan Hager, and Hayley Droppert for their searching, screening, and coding work on this review.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global HIV epidemic: 2010. 2010 Retrieved from: http://www.unaids.org/GlobalReport/

- 2.King R. Sexual behavioural change for HIV: Where have theories taken us? UNAIDs. 1999 Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/hiv/strategic/surveillance/en/unaids_99_27.pdf.

- 3.Cornman DH, Kiene SM, Christie S, et al. Clinic-based intervention reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: results of a pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:553–60. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bebd7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:594–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180415e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu F, Kilmarx PH, Supawitkul S, et al. Incidence of HIV-1 infection and effects of clinic-based counseling on HIV preventive behaviors among married women in northern Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:284–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200203010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. AHRQ Publication 08-05123-EF-2. 2008 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00010. Retrieved from http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf08/sti/stirs.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tan JY, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, Carey MP, Johnson BT. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of HIV/AIDS prevention interventions in Asia, 1995–2009. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(4):676–687. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, LaCroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: a meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(6):1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985-1997. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Sweat MD, Okero FA, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Aids & Behavior. 2013;17:1571–1590. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0241-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denison JA, O’Reilly KR, Schmid GP, Kennedy CE, Sweat MD. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: A meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDs Behavior. 2008;12:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonner VA, Denison J, Kennedy CE, O’Reilly K, Sweat M. The Cochrane Library. 2012. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries; p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]