Abstract

Sexual esteem is an integral psychological aspect of sexual health (Snell & Papini, 1989), yet it is unclear if sexual esteem is associated with sexual health behavior among heterosexual men and women. The current analysis uses a normative framework for sexual development (Lefkowitz & Gillen, 2006; Tolman & McClelland, 2011) by examining the association of sexual esteem with sexual behavior, contraception use, and romantic relationship characteristics. Participants (N = 518; 56.0% female; mean age = 18.43 years; 26.8% identified as Hispanic/Latino; among non-Hispanic/Latinos, 27.2% of the full sample identified as European American, 22.4% Asian American, 14.9% African American, and 8.7% multiracial) completed web-based surveys at a large northeastern university. Participants who had oral sex more frequently, recently had more oral and penetrative sex partners (particularly for male participants), and spent more college semesters in romantic relationships, tended to have higher sexual esteem than those who had sex less frequently, with fewer partners, or spent more semesters without romantic partners. Sexually active male emerging adults who never used contraception during recent penetrative sex tended to have higher sexual esteem than those who did use it, whereas female emerging adults who never used contraception tended to have lower sexual esteem than those who did use it. Implications of these results for the development of a healthy sexual self-concept in emerging adulthood are discussed.

Over half of individuals are sexually active by age 18 (Chandra, Mosher, & Copen, 2011), which suggests that sexual behavior is a normative part of the transition to adulthood (Lefkowitz & Gillen, 2006; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). Bancroft (2003) has challenged researchers to approach sexual development through a broader perspective, including psychological changes that are fundamental to the development of a sexual self. Understanding the development of sexual health behaviors (such as condom use) can inform safe sex interventions by identifying barriers to sexual health. Equally important for understanding the development of sexuality, however, is a positive youth development framework, which focuses on acquiring competencies that promote positive outcomes, not just reducing risk (Lerner, Almerigi, Theokas, & Lerner, 2005). As individuals transition to adulthood, they report more positive consequences (e.g. psychological and interpersonal) than negative consequences as a result of sexual behavior (Vasilenko, Lefkowitz, & Maggs, 2012). Therefore, understanding associations between sexual behaviors, the romantic contexts of those behaviors, and sexual esteem can inform positive youth development programs that not only focus on the reduction of risk behavior, but also on the promotion of competencies that lead to consensual, emotionally fulfilling, and more pleasurable sex.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2006) defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination, and violence (WHO, 2006). In response to the WHO’s thorough definition of sexual health, we aim to add to the growing body of research that focuses on positive psychological outcomes of sexual behavior, by examining not only sexual and contraception behaviors, but also psychological factors such as how individuals perceive themselves as sexual people.

A burgeoning area of research that explores multiple positive aspects of psychological sexual development has emerged. Such aspects include sexual self-efficacy, an individual’s perceived ability to successfully engage in and initiate a variety of sexual activities (Rosenthal, Moore, & Flynn, 1991); sexual competency, the ability to be involved in sexual practices with successful processes and outcomes (Hirst, 2008); sexual subjectivity, feelings of entitlement to sexual pleasure and sexual safety (Horne & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2005; Tolman, 2002), and the focus of this paper, sexual esteem, the tendency to view oneself as capable of relating sexually to another person (Snell & Papini, 1989) and to have an overall positive view of one’s sexual self. These constructs have shared commonalties, yet each identifies unique aspects of the developmental task of establishing a sexual self-concept during emerging adulthood.

This paper focuses on sexual esteem during emerging adulthood because it encompasses perceptions of the sexual self as well as perceptions of value to a sexual partner. Sexual esteem addresses both identity development and exploration of romantic relationships, which are primary developmental tasks during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Stein, Roeser, & Markus, 1998). Although individuals begin to explore identity and integrate sexuality into their self-concept during adolescence (Buzwell, Rosenthal, & Moore, 1992; O’Sullivan, Meyer-Bahlburg, & McKeague, 2006), emerging adulthood is a developmental period where this process is accelerated as individuals gain multiple sexual and romantic experiences (Arnett, 2000; Collins & Van Dulmen, 2006).

Previous research has linked sexual esteem to a variety of behavioral and psychological aspects of sexual well-being in female adolescents and female college students. For example, female adolescents with higher sexual esteem tend to have less disordered eating (Calogero & Thompson, 2009), more sexual agency and arousal (O’Sullivan et al., 2006), more motivation to avoid sexual risk-taking and to be more sexually satisfied (Schick, Calabrese, Rima, & Zucker, 2010), than female adolescents with lower sexual esteem. Further, sexual esteem mediates the association between child sexual abuse and sexual re-victimization in female college students (Van Bruggen, Runtz, & Kadlec, 2006). Yet, to our knowledge, sexual esteem research has predominately focused on women and has only been measured in young men in two studies, both with the purpose of measure development (Snell, Fisher, & Walters, 1993; Snell & Papini, 1989). Thus, very little is known about sexual esteem in male emerging adults or how male emerging adults differ from female emerging adults. In addition, little is known about the romantic relationship context of sexual esteem. The current research fills these gaps by testing associations between sexual esteem, sexual behavior, contraception use, and romantic relationships in a sample of male and female emerging adults.

Gender Differences in Sexual Esteem

Substantial evidence supports gender differences in sexual socialization and sexual behavior (Peplau, 2003), particularly in emerging adulthood. Thus, it is imperative to consider gender when examining correlates of sexual esteem. Men are socialized to enjoy sex, be sexually competent, and acquire many sex partners (Tolman, Striepe, & Harmon, 2003). Men are also more likely to report physiological sexual satisfaction, orgasms during intercourse, and permissive sexual attitudes (Higgins, Mullinax, Trussell, Davidson, & Moore, 2011). In contrast, women are sexually socialized to rely on men for their sexual gratification (Hogarth & Ingham, 2009) and sexual validation (Tolman, Striepe, & Harmon, 2003). Women also receive messages to be sexually attractive for and pleasing to men, instead of insisting on their own sexual pleasure (Morokoff, 2000; Tolman & Diamond, 2001). Feminist scholars argue that female sexual socialization impedes a woman’s sexual well-being because it promotes sexual objectification by men and self-objectification in women, making unwanted sexual experiences more likely to occur (Impett, Schooler, & Tolman, 2006). Moreover, in emerging adulthood, women have lower general self-esteem than men do (Galambos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006). Therefore, it is hypothesized that men will report higher sexual esteem than women will (Hypothesis 1).

Sexual Behavior and Sexual Esteem

Another potential correlate of sexual esteem is sexual behavior. For example, adolescent girls with more positive sexual self-concept tend to have engaged in a larger variety of sexual behaviors (Impett & Tolman, 2006). Although little work examines associations between sexual behavior and sexual esteem, there has been ample research on the association between sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction. For example, college students who have more frequent foreplay, oral sex, or penetrative sex are more satisfied with their sexual relationships than less satisfied students (Auslander et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2011). Yet, to our knowledge, no research examines how frequency of kissing, oral sex, or penetrative sex is associated with sexual esteem specifically. Kissing is a sexual behavior that is virtually free of negative physical consequences. Therefore, emerging adults can express and develop their sexuality through kissing without concern for STI infection or unwanted pregnancy. Kissing and oral sex in general are underrepresented in research on sexual behavior, despite their prevalence. Studies indicate that more adolescents have had oral sex than penetrative sex (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003; Schuster, Bell, & Kanouse, 1996). In a study of sexual behavior experienced before the first occasion of penetrative sex, 70% of males reported performing cunnilingus and 57% of females reported performing fellatio at least once prior to their first occasion of penetrative sex (Schwartz, 1999). Further, adolescents perceive oral sex as more prevalent, more acceptable, and as having fewer negative consequences than vaginal sex (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). However, adolescents who engage in oral but not vaginal sex are less likely to report experiencing pleasure or feeling good about themselves generally (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007). For instance, female adolescents report similar levels of pleasure from engaging in kissing, cunnilingus, and penetrative sex, but report less pleasure from performing fellatio than the other behaviors (Bay-Cheng, Robinson, & Zucker, 2009). In addition, Buzwell and Rosenthal (1996) theorized that sexual exploration is one of four key dimensions of adolescents’ sexual self-concept in addition to relationship commitment, sexual anxiety, and sexual arousal. However, what is unknown is how these sexual behaviors contribute to emerging adults’ views of their sexual selves. We predict that among emerging adults, having more frequent sexual behavior will be associated with higher sexual esteem because it offers another chance to practice the behavior and confirm one’s self-perception as a capable sex partner. Therefore, it is hypothesized that engaging in more frequent kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex will be associated with higher sexual esteem (Hypothesis 2).

Social norms that govern the appropriateness for number of sex partners differ between genders. For example, men are socialized to feel proud of having multiple sex partners (Smith, Guthrie, & Oakley, 2005), whereas women are shamed for having multiple sex partners (Tolman, 2002). Further, male college students who have a history of casual sex report fewer depressive symptoms than male college student who do not have casual sex, whereas female college students with a history of casual sex report more depressive symptoms than female college students who do not have casual sex (Grello, Welsh, & Harper, 2006). Therefore, the meaning of engaging in penetrative sex with one partner vs. sex with multiple partners will likely vary between genders. However, gender differences in experiences of other sexual behaviors are more nuanced. For example, adult women value and enjoy foreplay such as kissing more than men do and often prefer it over intercourse (Denney, Field, & Quadagno, 1984). In a recent study, male college students were more likely to report happiness and positivity about their first experiences of kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex than women were, and women felt more negative about engaging in first penetrative sex than men did (Vasilenko, Maas, & Lefkowitz, 2013). Because kissing and oral sex are perceived as having more positive consequences than vaginal sex, we hypothesize that having more kissing and oral sex partners will be associated with higher sexual esteem (Hypothesis 3). However, due to gender differences in the meaning of number of penetrative sex partners, we predict that having more penetrative sex partners will be associated with higher sexual esteem in men and lower sexual esteem in women (Hypothesis 4).

Contraception Use and Sexual Esteem

The majority of research on contraception use focuses on the absence of disease and prevention of unwanted pregnancy (As-Sanie, Gantt, & Rosenthal, 2004). However, less attention is paid to how contraception use is associated with psychological well-being (Philpott, Knerr, & Boydell, 2006). What is known in this area is that less consistent condom and contraception use is associated with more sexual guilt among college students (Hynie, Macdonald, & Marques, 2006; Moore & Davidson, 1997), whereas more condom use self-efficacy is associated with more sexual subjectivity, or more feelings of entitlement to sexual pleasure and sexual safety among female college students (Schick, Zucker, & Bay-Cheng, 2008). In addition, emerging adults who more frequently use condoms during sex are more satisfied with their sexual relationship than those who use condoms less during sex (Auslander et al., 2007). However, condom use can decrease pleasure among adult men and women (Hensel, Stupiansky, Herbenick, Dodge, & Reece, 2012; Higgins, Hoffman, Graham, & Sanders, 2008), whereas, hormonal birth control use is associated with decreased sexual desire among adult women (Gracia et al., 2010). Previous research has found that greater motivation to avoid unprotected sexual behavior is associated with higher sexual esteem among female emerging adults (Schick et al., 2010). In regard to the physical aspect of the sexual self, female college students who report less risky sexual behavior have more positive body image, whereas male college students who report more risky sexual behavior have more positive body image (Gillen, Lefkowitz, & Shearer, 2006). To our knowledge, associations between and gender differences in contraception use and sexual esteem have not been tested. However, based on prior research on gender, contraception use, and sexual satisfaction, we predict that contraception use will be associated with higher sexual esteem in women and lower sexual esteem in men (Hypothesis 5).

Sexual Esteem in Romantic Relationships

Romantic relationships provide a context for sexual behavior to occur with the same person in tandem with other interpersonal exchanges (Impett, Muise, & Peragine, 2013). Therefore, the experience of sexual behavior with romantic relationship partners provides a different context for the development of sexual esteem than the same behaviors with non-committed partners (Impett et al., 2013). However, research has primarily focused on the role romantic relationships play in sexual satisfaction, with very little attention paid to sexual esteem. For example, sexually active Norwegian adults who are in a romantic relationship are more satisfied with their sex lives than adults who are not in a romantic relationship (Pedersen & Blekesaune, 2003). Additionally, American college students in serious romantic relationships experience greater sexual satisfaction than college students who are single or in casual relationships (Higgins et al., 2011). Yet, less is known about the association between romantic relationship status and the perception of one’s sexual self. Based on prior research on sexual satisfaction within romantic relationships, we predict that emerging adults who are currently in a romantic relationship and have spent more college semesters in a romantic relationship will have higher sexual esteem than those who are not currently in a romantic relationship or have spent fewer college semesters in a romantic relationship (Hypothesis 6).

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Data are from The University Life Study, a longitudinal study at a large northeastern university in the United States. All prospective participants were U.S. citizens or permanent residents, in their first year of college, and 16-20 years old. A stratified random sampling procedure was used to oversample ethnic/racial minorities in order to achieve a diverse sample. In total, there was a 65.6% response rate with 744 students providing informed consent and participating in the Semester 1 (Fall, 2007) survey. Data collection occurred each Fall and Spring semester over the course of seven semesters. Between Semester 1 and Semester 5, there was a 72.9% retention rate with 620 students participating in Semester 5 (Fall, 2009). Participants completed web-based surveys each semester via a secure link and were compensated $20/survey (Semester 1) and $40/survey (Semester 5), with compensation increasing as an incentive to continue participation.

Students who at Semester 5 did not participate, were missing any sexual behavior item, or missing more than half of the sexual esteem items were dropped from analyses, resulting in an analytic sample for the current paper of 518 students. The analytic sample was 56.0% female and 97.7% heterosexual with a mean age of 18.43 (SD = .41) years old at Semester 1. In the analytic sample, 26.8% identified as Hispanic/Latino. Among non-Hispanic/Latinos, 27.2% of the full sample identified as European American, 22.4% Asian American, 14.9% African American, and 8.7% multiracial. Regarding religion, 37.8% were Catholic, 34.2% Protestant/Christian, 2.6% Jewish, 1.0% Muslim Islamic, 8.5% followers of another religion (e.g., Buddhism, Hinduism), and 17.1% were not religious. Based on participant report, 6.1% of the participants’ mothers and 8.8% of fathers did not complete high school, 17.7% of mothers and 16.7% of fathers completed high school, 37.1% of mothers and 32.1% of fathers completed college, 21.0% of mothers and 29.2% of fathers completed graduate school, 1.4% of participants did not report their mothers’ education, and 3.5% did not report their fathers’ education. Participants with missing data did not differ on sexual history from those without missing data.

To compare students from our analytic sample (N = 518) to students who participated in Semester 1 but were not in our analytic sample (N = 226), a series of 17 Χ2 and t-tests on demographic and other variables used in our analyses was performed. The analytic sample did not differ from excluded participants on Semester 1 age, race/ethnicity, parents’ education, sexual behaviors, or romantic relationship status (p > .05). However, there were more female participants and more participants who identified as Catholic in our analytic sample (p < .05) compared to excluded participants. Differences in sexual esteem could not be tested because sexual esteem was only measured in Semester 5 and differences on romantic relationship history could not be tested because that variable was created with data from semesters 1 through 5.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their gender, date of birth (used to calculate age), ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, religion, and mothers’ and fathers’ education.

Sexual esteem

At Semester 5, participants completed the sexual esteem subscale from The Sexuality Scale (Snell & Papini, 1989), a 10-item subscale that evaluates one’s sexual self (e.g. “I am a good sexual partner,” “I sometimes have doubts about my sexual competence”). Participants responded using a Likert-type scale with values that ranged from 0-4. This measure had acceptable reliability in the current sample (α =.92).

Kissing Frequency

Participants were first asked at Semester 1, “Have you and a partner ever kissed each other on the lips?” If they responded “no” they were asked this question again at each semester until they responded “yes.” Once they responded “yes” participants were asked at each semester, “In the past 12 weeks, have you and a partner kissed on the lips?” If they responded “yes”, they were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, on how many occasions have you kissed someone on the lips?” We recoded responses that were over 100 (44 responses) to 100, given that anything over 100 represented more than once per day, and that these large numbers (as high as XXXX) increased variable skew.

Oral Sex Frequency

The same procedure described for kissing frequency was used to measure oral sex frequency. Participants were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, on how many occasions have you performed oral sex on a partner?” and “In the past 12 weeks, on how many occasions has a partner performed oral sex on you?” Frequency for performed oral sex and received oral sex were highly correlated (INSERT HERE), and thus were combined to create oral sex frequency. Thus, this number is likely an overestimate of oral sex frequency because if someone received and performed oral sex on the same occasion, it would be counted as two occasions in this analysis. We recoded responses that were over 100 (3 responses) to 100.

Penetrative Sex Frequency

The same procedure described above for kissing frequency was used to measure penetrative sex frequency. Participants were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, on how many occasions have you had vaginal and/or anal sex?” We recoded responses that were over 100 (2 responses) to 100.

Kissing Partners

Participants who responded “yes” to having kissed someone in the past 12 weeks were then asked, “In the past 12 weeks, how many different female partners have you kissed on the lips?”, and a parallel question about male partners. The total number of male and female partners was then summed to create the number of recent kissing partners.

Oral Sex Partners

The same procedure described for kissing partners was used to measure number of oral sex partners. Participants were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, how many different (female/male) partners have you performed oral sex on?” and “In the past 12 weeks, how many different (female/male) partners have performed oral sex on you?” Number of partners performed oral sex on and received oral sex from were combined and the total number of male and female partners was then summed in order to create the number of recent oral sex partners. As with oral sex frequency, this number is likely an overestimate.

Penetrative Sex Partners

The same procedure described above for kissing partners was used to measure number of penetrative sex partners. Separate questions for female and male partners were not asked of female participants because in this study, we defined penetrative sex as sex in which the penis penetrates the vagina or anus. Female participants were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, how many different male partners have you had vaginal and/or anal sex with?” and male participants were asked two separate questions about male and female partners. Numbers of male and female penetrative sex partners were summed for male participants to indicate their total number of penetrative sex partners.

Contraception Use

Participants who reported having penetrative sex in the past 12 weeks were asked, “In the past 12 weeks, how frequently did you use any method to prevent pregnancy or disease including condoms when you had vaginal and/or anal sex?” Participants responded on a Likert-type scale that ranged from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“every time”). We then created a dichotomous variable (0 = “never” and 1 = “some of the time” to “every time”) to compare participants who never used contraception during recent sex to those who used contraception.

Romantic Relationship Status

To assess relationship status, participants were asked “Which of the following best describes you right now?” We dichotomized responses (0 =“not in a serious relationship”, which included individuals who responded that they were either not dating anyone or casually dating someone and 1 =“in a serious relationship”, which included those who were in a committed relationship, living with a partner, engaged, or married).

Romantic Relationship History

We created a variable that added participants’ dichotomized romantic relationship status at each semester (Semester 1-Semester 5) to create a score from 0 (never in a romantic relationship) to 5 (in a romantic relationship every semester). This variable was created to distinguish students who tend to be in serious romantic relationships from students who tend to not be in serious romantic relationships in addition to testing their current romantic relationship status.

Analysis Plan

We used 2 separate linear regression models with sexual esteem as the outcome to test associations with sexual esteem in our sample and a sub-sample. Model 1 tested hypotheses 1 (men will report higher sexual esteem than women will), 2 (engaging in more frequent kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex will be associated with higher sexual esteem), 3 (having more kissing and oral sex partners will be associated with higher sexual esteem), 4 (having more penetrative sex partners will be associated with higher sexual esteem in men and lower sexual esteem in women), and 6 (emerging adults who are currently in a romantic relationship and have spent more college semesters in a romantic relationship will have higher sexual esteem than those who are not currently in a romantic relationship or have spent fewer college semesters in a romantic relationship). Model 1 included the full analytic sample, with gender, frequency of kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex, number of kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex partners, romantic relationship status, romantic relationship history, and three number of partners (kissing/oral sex/penetrative sex) by gender interaction terms as the predictors. We created the interaction terms by first centering gender and then multiplying the centered gender variable by number of (kissing/oral sex/penetrative sex) partners.

Model 2 tested hypothesis 5 (contraception use will be associated with higher sexual esteem in women and lower sexual esteem in men), which included only participants who had penetrative sex in the 12 weeks prior to data collection (N = 234). In addition to the predictors in Model 1, Model 2 also included contraception use and a gender by contraception use interaction term. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20.0.

RESULTS

Means and standard deviations of variables are presented in Table 1. Bivariate correlations of variables separated by gender are shown in Table 2. In Model 1, a 2 step hierarchical regression procedure was used to test hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 (see Table 3) in the full analytic sample (N = 518). We hypothesized that male emerging adults would have higher sexual esteem than female emerging adults (Hypothesis 1). However, male and female participants did not differ on sexual esteem in our multivariate model, nor in the bivariate correlation (r = .01, p > .05). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Semester 5 Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Esteem1 | 2.50 | 0.78 | .00 | 4.00 |

| Kissing Frequency2 | 23.79 | 35.79 | .00 | 100.00 |

| Oral Sex Frequency | 4.25 | 11.49 | .00 | 100.00 |

| Penetrative Sex Frequency | 8.21 | 18.26 | .00 | 100.00 |

| Kissing Partners3 | 1.36 | 1.96 | .00 | 28.00 |

| Oral Sex Partners | 0.96 | 1.49 | .00 | 12.00 |

| Penetrative Sex Partners | 0.57 | 0.81 | .00 | 6.00 |

| Contraception Use4 | .85 | .36 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Romantic Relationship Status5 | .31 | .46 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Romantic Relationship History6 | 1.46 | 1.65 | .00 | 5.00 |

Note.

Sexual Esteem was measured on a 0 to 4 point Likert-type scale.

Frequency was measured as number of sexual behavior occasions over a 12-week period (range 0-100).

Partners were measured as number of sex partners over a 12-week period.

Contraception Use was dichotomized to “never” (0) and “sometimes to always” (1).

Romantic Relationship Status was dichotomized to “not in a serious relationship” (0) and “in a serious relationship” (1).

Romantic Relationship History was measured as number of semesters the participant spent in a romantic relationship.

Table 2.

Correlations of Variables Separated by Gender

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual Esteem | -- | .29*** | .27*** | .26*** | .18*** | .33*** | .15** | .08 | .25*** | .34*** |

| 2. Kissing Frequency | .26*** | -- | .53*** | .59** | .06 | .34*** | .24* | .11 | .54*** | .42** |

| 3. Oral Sex Frequency | .28*** | .57*** | -- | .66*** | .03 | .29*** | .18** | .05 | .33*** | .28*** |

| 4. Pen Sex Frequency1 | .25*** | .64*** | .64*** | -- | .05 | .34*** | .32** | .07 | .43*** | .30** |

| 5. Kissing Partners | .25*** | .06 | .07 | .08 | -- | .37*** | .43** | .05 | −.11* | −.02 |

| 6. Oral Sex Partners | .37*** | .25*** | .28*** | .25*** | .73*** | -- | .58*** | −.01 | .21*** | .22*** |

| 7. Pen Sex Partners2 | .39*** | .27*** | .24*** | .33*** | .58*** | .68*** | -- | −.01 | .11 | .19** |

| 8. Contraception Use | −.19* | .03 | .00 | −.04 | −.17 | −.17 | −.14 | -- | .03 | .14 |

| 9. Relationship Status | .26*** | .58*** | .29*** | .33*** | −.03 | .19*** | .12* | .01 | -- | .66*** |

| 10. Relationship History | .29*** | .46*** | .25*** | .32*** | .04 | .27*** | .27*** | −.05 | .67*** | -- |

Note. Female emerging adults’ correlations above the diagonal, male emerging adults’ correlations below the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01,

p < .001. Female emerging adults (N = 118-334). Male emerging adults (N = 77-286).

Penetrative Sex Frequency

Penetrative Sex Partners

Table 3.

Standardized Coefficients in Linear Regressions Predicting Sexual Esteem

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytic Sample (N = 518) | Sexually Active1 (N =234) | |||||

| β | R2 | Δ R2 | β | R2 | Δ R2 | |

| Step 1 | .22*** | -- | .07 | -- | ||

| Gender | .06 | .07 | ||||

| Kissing Frequency | .04 | −.10 | ||||

| Oral Sex Frequency | .11* | .16 | ||||

| Penetrative Sex Frequency | −.02 | .03 | ||||

| Kissing Partners | .08 | −.03 | ||||

| Oral Sex Partners | .13* | .11 | ||||

| Penetrative Sex Partners | .15* | .07 | ||||

| Contraception Use | -- | −.01 | ||||

| Relationship Status | .04 | .05 | ||||

| Relationship History | .20*** | .07 | ||||

| Step 2 | .24*** | .01* | .12** | .06** | ||

| Gender | .06 | .20 | ||||

| Kissing Frequency | .03 | −.12 | ||||

| Oral Sex Frequency | .12* | .19* | ||||

| Penetrative Frequency | −.04 | −.01 | ||||

| Kissing Partners | .06 | −.08 | ||||

| Oral Sex Partners | .12* | .10 | ||||

| Penetrative Partners | .19** | .17* | ||||

| Contraception Use | -- | −.04 | ||||

| Relationship Status | .05 | .10 | ||||

| Relationship History | .19*** | .07 | ||||

| Gender*Kissing Partners | −.09 | −.15 | ||||

| Gender*Oral Sex Partners | −.10 | −.15 | ||||

| Gender*Penetrative Partners | .18** | .43** | ||||

| Gender*Contraception Use | -- | −.34* | ||||

Note.

† p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p .001

Sexually Active = had penetrative sex in the last 12 weeks.

We hypothesized that more frequent kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex would be associated with higher sexual esteem (Hypothesis 2). In Model 1, having more frequent oral sex was associated with higher sexual esteem. Kissing more frequently and having more frequent penetrative sex were not associated with sexual esteem in the full model (see Table 3), although all three sexual behaviors were associated with higher sexual esteem in the bivariate correlations (see Table 2). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

We hypothesized that having more kissing and oral sex partners would be associated with higher sexual esteem (Hypothesis 3). In Model 1, having more kissing partners was not associated with higher sexual esteem, but having more oral sex partners was (see Table 3), and both were associated with sexual esteem in the bivariate correlations (see Table 2). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

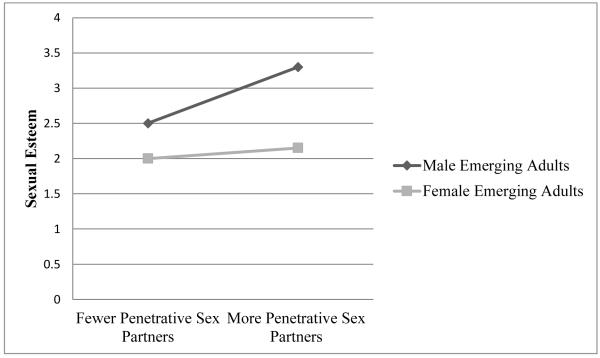

We hypothesized that having more penetrative sex partners would be associated with higher sexual esteem in male emerging adults and lower sexual esteem in female emerging adults (Hypothesis 4). In Model 1, the change in R2 for Step 2 was significant, indicating that the addition of the interactions increased the amount of explained variance in sexual esteem (see Table 3). The gender and penetrative partners interaction term was significant. As seen in Figure 1, follow-up regression analyses (not shown) separated by gender revealed that female emerging adults’ number of penetrative sex partners was not significantly associated with sexual esteem when other variables were in the model (□□□□□□□□p > .05). However, having more penetrative sex partners was associated with higher sexual esteem for male emerging adults (□□□□□□□□p < .001), although in the bivariate correlations, penetrative sex partners were associated with sexual esteem for both male and female emerging adults. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

Figure 1.

Sexual Esteem and Penetrative Sex Partners Moderated by Gender

Note. Low penetrative sex partners = 1 standard deviation below the mean (approx. 0 partners). High penetrative sex partners = 1 standard deviation above the mean (approx. 2 partners).

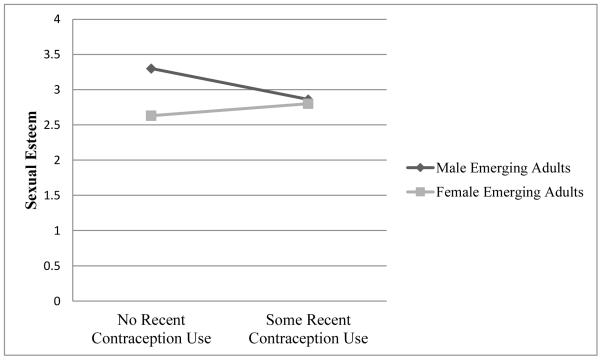

We hypothesized that not using contraception would be associated with higher sexual esteem in male emerging adults and lower sexual esteem in female emerging adults (Hypothesis 5). In Model 2 with the subsample of recently sexually active participants (N = 234), the change in R2 for step 2 was significant, indicating that the addition of the interactions increased the amount of explained variance in sexual esteem (see Table 3). The interaction between gender and contraception use was significant. As seen in Figure 2, male participants who never used contraception tended to have higher sexual esteem (M = 3.30, SD = .64) than those who used it (M = 2.86, SD = .80), whereas female participants who never used contraception tended to have lower sexual esteem (M = 2.63, SD = .59) than those who used it (M = 2.80, SD = .74). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Figure 2.

Sexual Esteem and Contraception Use Moderated by Gender

We hypothesized that currently being in a romantic relationship and having spent more college semesters in a romantic relationship would be associated with higher sexual esteem (Hypothesis 6). In Model 1, being in a romantic relationship was not associated with sexual esteem (see Table 3), but it was associated in our bivariate correlations (see Table 2). Having spent more semesters throughout college in a romantic relationship was significantly associated with higher sexual esteem in our multivariate model (see Table 3) and in our bivariate correlations (see Table 2). Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was partially supported.

DISCUSSION

We used data from a longitudinal study of college students to explore associations between sexual esteem and sexual behavior, contraception use, and romantic relationship experience. Contrary to our hypothesis, male and female emerging adults did not differ in sexual esteem. This finding was unexpected given that male emerging adults have higher global self-esteem than female emerging adults (Galambos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006) and men are socialized to be more sexual than women (Tolman & Diamond, 2001). Although we did not find gender differences in sexual esteem, we did find gender differences in the association between sexual esteem and frequency of penetrative sex and the association between sexual esteem and contraception use, which indicates that the development of sexual esteem includes different processes for men and women.

Engaging in more frequent kissing, oral sex, and penetrative sex was associated with higher sexual esteem, indicating the importance of experience with a variety of sexual behaviors when constructing views of one’s sexual self. Kissing is perhaps the safest sexual behavior, providing a chance to engage in sexual behavior without contradicting one’s ideologies about penetrative sex and risk or morality. Penetrative sex is typically valued and enjoyed by both young men and women (Higgins et al., 2011).Yet, penetrative sex carries the most potential physical health risks of all types of sexual behavior, which could evoke a combination of positive and negative feelings depending upon the safety measures taken during penetrative sex. In contrast, adolescents evaluate oral sex as having fewer social, emotional and health risks, judge oral sex to be more acceptable in dating and non-dating relationships, and consider oral sex less threatening to their values and beliefs than penetrative sex (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007). Therefore, in emerging adulthood, oral sex is a sexual behavior that is possibly more intimate and pleasurable than kissing and poses less potential health risks than penetrative sex. These cost/benefit differences could explain why having more frequent oral sex remained significantly associated with higher sexual esteem in our multivariate model, whereas engaging in more frequent kissing or penetrative sex did not remain significant. However, it is also likely that individuals with higher sexual esteem would be more likely to engage in more frequent sexual behavior than those lower in sexual esteem.

Having more kissing and oral sex partners was associated with higher sexual esteem for both genders. Similar to engaging in kissing and oral sex more frequently, it is likely that having more kissing and oral sex partners is associated with higher sexual esteem because kissing and oral sex are perceived more positively than penetrative sex among adolescents (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007). It is also less likely for individuals to count oral sex partners in their tabulation of their lifetime sex partners (Wiederman, 1997), making one’s number of kissing and oral sex partners even less of a threat to one’s sexual self-view, particularly for female emerging adults. Again, because sexual esteem reflects one’s value of one’s self as a sexual partner (Snell & Papini, 1989), it is also likely that those who have higher sexual esteem are also likely to pursue more sexual partners.

In partial support of our hypothesis, having more penetrative sex partners was associated with higher sexual esteem for male emerging adults but not for female emerging adults. Given that men are socialized to have multiple sex partners, whereas women are socialized to have sex with fewer partners in the context of committed relationships (Tolman, 2002; Tolman & Diamond, 2001), the importance of having more sex partners for men’s sexual esteem may reflect this differential socialization. It should be noted that we focused only on recent sex partners, which may not be representative of one’s lifetime sex partners because an individual could have had more sex partners in the past. Future research should test gender differences in sexual esteem and lifetime sex partners to better understand the association between sex partners over time and one’s view of one’s sexual self.

Never using contraception during recent penetrative sex was associated with higher sexual esteem in male emerging adults and lower sexual esteem in female emerging adults. These findings corroborate previous research that suggests a link between risky sexual behavior and more positive body image and mental health among men but not women (Gillen et al., 2006; Grello et al., 2006). Through the lens of hegemonic masculinity, men are more privileged sexually and therefore can insist on experiencing pleasure and passion over responsibility, whereas women bear the responsibilities of unwanted pregnancy and negative sexual stereotyping, making their sexual choices more burdensome (Oudshoorn, 2004; Tolman, 2002; Tolman & Diamond, 2001; Tolman et al., 2003). Since the invention of hormonal birth control in the 1960s, the responsibility for contraception has predominantly been delegated to women, which consequently excludes contraception from hegemonic masculinity (Oudshoorn, 2004). From this perspective, choosing not to use contraception would be a symbol of masculine power and sexual agency, which could align with a man’s more positive sexual self-concept. In contrast, female emerging adults who have a more positive sexual self-concept are likely more able to assert themselves in a sexual situation and therefore insist on using contraception. However, this analysis does not differentiate between the type of contraception used, so it is difficult to extrapolate the meaning of this gender difference without knowing if male-initiated contraception (such as a condom) was used or a female-initiated contraception (such as the hormonal birth control pill) was used. For example, men who have a partner who uses hormonal birth control may have higher sexual esteem than men who use a condom, as hormonal birth control does not interfere with the male partner’s pleasure. Therefore, it is important for future work to ask about multiple types of contraception as well as a participant’s partner’s use of contraception.

Currently being in a romantic relationship and having spent more college semesters in romantic relationships were associated with higher sexual esteem. However, in the context of other correlates, only relationship history was associated with higher sexual esteem. It could be that our relationship history variable captured more of the variance in sexual esteem because it was more relevant to the developmental aspect of sexual esteem, whereas current relationship status only captured a current snapshot. Prior research has indicated that sexual behavior outside of relationships is associated with guilt (Vasilenko et al., 2012), so it is possible that sexually active individuals who spend less time in romantic relationships have less opportunity to develop sexual esteem and more opportunity for feelings of sexual guilt to develop. It could also be that spending time in a relationship confirms one’s confidence as a sex partner, whereas spending more time without a romantic partner triggers feelings of sexual inadequacy because there is not a romantic partner around to confirm positive views of one’s sexual self. However, it is also likely that those who have higher sexual esteem are more likely to seek out potential romantic partners and perhaps even attract more potential romantic partners.

There are several limitations to this paper that deserve mention. Although our sample was more diverse than prior studies of sexual esteem, our results are specific to students attending 4-year residential universities and cannot be generalized to other college-attending populations or non-college attending populations. For example, sexual expression may carry a different meaning for sexual esteem among college students who attend a religious-affiliated university and among emerging adults who do not attend college at all.

Additionally, we only measured sexual behavior over a 12 week period which increases accuracy in recall (Stone, Bachrach, Jobe, Kurtzman, & Cain, 1999), but may not be representative of an individual’s lifetime sexual behavior. Due to their high correlation with each other, we combined the receiving with performing oral sex, despite the fact that they are experienced in different ways (Bay-Cheng et al., 2009)). Future research should consider exploring the distinct roles fellatio and cunnilingus play in sexual self-concept, perhaps using daily measures. Similarly, we did not differentiate vaginal sex from anal sex, nor penetrative sex experienced with same-sex or different-sex partners, although these behaviors may differentially relate to sexual esteem. We also analyzed sexual behavior and sexual esteem at the same time and therefore could not determine the temporal ordering of behaviors and sexual esteem. Engaging in a variety of sexual behaviors may foster development of sexual esteem, but it is also possible that individuals with higher sexual esteem are more likely to engage in a variety of sexual behaviors. Clarification of the temporal ordering of sexual behavior and sexual esteem could be achieved through measuring sexual behavior and sexual esteem repeatedly over time, particularly across developmental stages to determine if the development of sexual esteem occurs through experience or age. In addition, testing potential moderators of the association between sexual behavior and sexual esteem, such as ethnicity, religiosity, sexual media use, and participation in comprehensive sexuality education would also help to explain how one’s view of his/her sexual self develops within an ecological context (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998).

Finally, our hypotheses and results can only be applied to heterosexual individuals and reflect heterosexual development and heterosexual socialization. Although we know little about positive and negative outcomes of sexual behavior for sexual minorities, research thus far suggests that due to some unique identity processes and social experiences for sexual minority youth, some outcomes may differ by sexual orientation (Morgan, 2014). Therefore, it would be important to explore sexual esteem in sexual minorities, because this knowledge would not only deepen our understanding of how sexual minority individuals perceive their sexual selves, it would also provide a greater understanding of determining whether gender differences in the associations between sexual esteem and contraception use or penetrative sex partners occur across all sexual identities or only among heterosexual emerging adults.

Our findings contribute to sexual development research in several ways. First, a major strength of this analysis was our sample. Prior research on associations with sexual esteem has primarily been conducted with White, female college students without assessing their relationship status. Our sample included male college students, was more ethnically and racially diverse, and examined associations with relationship characteristics. Second, this research examined associations between sexual health behavior (contraception use) and a positive developmental outcome (sexual esteem), contributing to our understanding of the dynamic nuances that are associated with sexual health behaviors. Third, this research illustrates how sexual behaviors in emerging adulthood may be important to the development of an individual’s sense of him/herself as a sexual being. Frequent and positive sexual experiences are potentially important as emerging adults transition into young adulthood, when sexual competency is required to maintain healthy, long-term, and committed romantic partnerships (Impett et al., 2013; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005). Fourth, the implication of sexual esteem’s association with men’s lower contraception use is of particular concern because the repercussions of unwanted pregnancy or contracting an STI from not using contraception can be damaging to both partners. About one quarter of all new HIV infections and nearly half of all other new STIs occur in people ages 15-24 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011a; 2011b), suggesting the need to target this age group, particularly men, who are less inclined to use contraception when they feel positive about their sexual self. Therefore, if sexuality education efforts addressed sexual socialization processes that connect sexual health behavior with masculinity, boys and young men could be more cognizant of why they are not using contraception and therefore may be more likely to change their behavior. If boys and men remain unaware of sexual socialization processes, increasing positive perceptions of their sexual selves may actually be more harmful, as higher sexual esteem is associated with riskier sexual behavior among male emerging adults. However, for adolescent girls and young women, sexuality education could emphasize the association between higher sexual esteem and contraception use with the intent to further foster sexual agency.

Future researchers should also consider measuring multiple aspects of positive sexuality such as sexual self-efficacy, sexual competency, and sexual subjectivity in addition to sexual esteem within the same study in order to further differentiate the constructs and identify unique correlates. It would be particularly beneficial to determine which aspects of positive sexuality are associated with more sexual health behaviors and fewer sexual risk-taking behaviors. This information could potentially transform the way we approach prevention of sexual risk-taking by both reducing risk and promoting health simultaneously.

In conclusion, relationship history and sexual behavior were associated with sexual esteem. Sexual esteem was associated with less contraception use and more penetrative sex partners among men and more contraception use among women, highlighting the differential association for young men vs. young women. Overall, sexual esteem is an integral part of the development of physical, emotional, and social sexual health competencies at a developmental period when it is essential to establish sexual competencies and a sexual identity (Arnett, 2000). Taking a more holistic approach by including not only sexual health behaviors, but the context in which those behaviors occur and the self-perception those behaviors produce, would further the study and development of theoretical models of sexual health in emerging adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol and Alcoholism under the principle investigation of Jennifer L. Maggs, Ph.D. We thank our colleagues Sara Vasilenko, Nicole Morgan, and Meg Small who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted this research, although they may not agree with all of the interpretations/conclusions of this paper.

Contributor Information

Megan Maas, Human Development & Family Studies, The Pennsylvania State University, Phone: 415-606-0952, Fax: 814-863-7005, 315-A East Health & Human Development Building, University Park, PA 16802

Eva Lefkowitz, Human Development & Family Studies, The Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- As-Sanie S, Gantt AN, Rosenthal MS. Pregnancy prevention in adolescents. American Family Physician. 2004;70:1517–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auslander BA, Rosenthal SL, Fortenberry JD, Biro FM, Bernstein DI, Zimet GD. Predictors of sexual satisfaction in an adolescent and college population. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2007;20:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.006. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J. Introduction. In: Bancroft J, editor. Sexual development in childhood. Indiana University Press; Bloomington, IN: 2003. pp. xi–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Cheng LY, Robinson AD, Zucker AN. Behavioral and relational contexts of adolescent desire, wanting, and pleasure: Undergraduate women's retrospective accounts. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:511–524. doi: 10.1080/00224490902867871. doi:10.1080/00224490902867871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents' reported consequences of having oral sex versus vaginal sex. Pediatrics. 2007;119:229–236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1727. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Volume 1: Theoretical models of human development. 5th John Wiley & Sons Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Buzwell S, Rosenthal D. Constructing a sexual self: Adolescents’ sexual self-perceptions and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Buzwell S, Rosenthal DA, Moore SM. Idealising the sexual experience. YSA Resources. 1992;1:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Calogero RM, Thompson JK. Sexual self-esteem in American and British college women: Relations with self-objectification and eating problems. Sex Roles. 2009;60:160–173. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2011a Retrieved August 19, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_Adolescents.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. 2011b Retrieved August 19, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/Surv2011.pdf.

- Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006-2008 national survey of family growth. National Health Statistics Reports. 2011;36:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Van Dulmen M. Friendships and Romance in Emerging Adulthood: Assessing Distinctiveness in Close Relationships. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Denney NW, Field JK, Quadagno D. Sex differences in sexual needs and desires. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1984;13:233–245. doi: 10.1007/BF01541650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:350–365. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES, Shearer CL. Does body image play a role in risky sexual behavior and attitudes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:230–242. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9005-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia CR, Sammel MD, Charlesworth S, Lin H, Barnhart KT, Creinin MD. Sexual function in first-time contraceptive ring and contraceptive patch users. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;93:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.066. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grello CM, Welsh DP, Harper MS. No strings attached: The nature of casual sex in college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:255–267. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552324. doi:10.1080/00224490609552324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel DJ, Stupiansky NW, Herbenick D, Dodge B, Reece M. Sexual pleasure during condom-protected vaginal sex among heterosexual men. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9:1272–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02700.x. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Graham CA, Sanders SA. Relationships between condoms, hormonal methods, and sexual pleasure and satisfaction: An exploratory analysis from the Women's Well-Being and Sexuality Study. Sexual Health. 2008;5:321–330. doi: 10.1071/sh08021. doi: 10.1071/SH08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Mullinax M, Trussell J, Davidson JK, Sr, Moore NB. Sexual satisfaction and sexual health among university students in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:1643–1654. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J. Developing sexual competence? Exploring strategies for the provision of effective sexualities and relationships education. Sex Education. 2008;8:399–413. doi:10.1080/14681810802433929. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth H, Ingham R. Masturbation among young women and associations with sexual health: An exploratory study. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:558–567. doi: 10.1080/00224490902878993. doi:10.1080/00224490902878993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne S, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Female sexual subjectivity and well-being: Comparing late adolescents with different sexual experiences. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2005;2:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hynie M, MacDonald TK, Marques S. Self-conscious emotions and self-regulation in the promotion of condom use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:1072–1084. doi: 10.1177/0146167206288060. doi:10.1177/0146167206288060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Muise A, Peragine D. Sexuality in the context of relationships. In: Diamond L, Tolman D, editors. APA handbook of sexuality and psychology. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2013. pp. 269–316. [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Schooler D, Tolman DL. To be seen and not heard: Femininity ideology and adolescent girls’ sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:129–142. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9016-0. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-9016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Tolman DL. Late adolescent girls’ sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:628–646. doi:10.1177/0743558406293964. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM. “Sex is just a normal part of life”: Sexuality in emerging adulthood. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Almerigi JB, Theokas C, Lerner JV. Positive youth development. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Litzinger S, Gordon K. Exploring relationships among communication, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2005;31:409–424. doi: 10.1080/00926230591006719. doi:10.1080/00926230591006719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters NT, Casey E, Wells EA, Morrison DM. Sexual scripts among young heterosexually active men and women: Continuity and change. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:409–420. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.661102. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.661102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore NB, Davidson JK., Sr Guilt about first intercourse: An antecedent of sexual dissatisfaction among college women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1997;23:29–46. doi: 10.1080/00926239708404415. doi:10.1080/14681810600982093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ. Sexuality, society, and feminism. In: Travis CB, White JW, editors. Psychology of Women. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM. Outcomes of sexual behaviors among sexual minority youth. In: Lefkowitz ES, Vasilenko SA, editors. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development: Positive and negative outcomes of sexual behavior. Vol. 144. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2014. pp. 21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, McKeague IW. The development of the sexual self-concept inventory for early adolescent girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:139–149. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00277.x. [Google Scholar]

- Oudshoorn N. “Astronauts in the sperm world”: The renegotiation of masculine identities in discourses on male contraceptives. Men and Masculinities. 2004;6:349–367. doi:10.1177/1097184X03260959. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W, Blekesaune M. Sexual satisfaction in young adulthood cohabitation, committed, dating or unattached life? Acta Sociologica. 2003;46:179–193. doi:10.1177/00016993030463001. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA. Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:37–40. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01221. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott A, Knerr W, Boydell V. Pleasure and prevention: When good sex is safer sex. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14:23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28254-5. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Meade CS, Cohen GL. Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends' sexual behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:243–249. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D, Moore S, Flynn I. Adolescent self-efficacy, self-esteem and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 1991;1:77–88. doi:10.1002/casp.2450010203. [Google Scholar]

- Schick VR, Calabrese SK, Rima BN, Zucker AN. Genital appearance dissatisfaction: Implications for women’s genital image self-consciousness, sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and sexual risk. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34:394–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01584.x. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick VR, Zucker AN, Bay-Cheng LY. Safer, better sex through feminism: The role of feminist ideology in women's sexual well-being. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:225–232. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00431.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Bell RM, Kanouse DE. The sexual practices of adolescent virgins: Genital sexual activities of high school students who have never had vaginal intercourse. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1570–1576. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1570. doi:10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz IM. Sexual activity prior to coital initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1999;28:63–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1018793622284. doi:10.1023/A:1018793622284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LH, Guthrie BJ, Oakley DJ. Studying adolescent male sexuality: Where are we? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:361–377. doi:10.1007/10964-005-5762-5. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Jr., Fisher TD, Walters AS. The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire: An objective self- report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Annals of Sex Research. 1993;6:27–55. doi:10.1007/BF00849744. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Jr., Papini DR. The sexuality scale: An instrument to measure sexual-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation. Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:256–263. doi:10.1080/00224498909551510. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. Psychology Press; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL. Dilemmas of desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Diamond LM. Desegregating sexuality research: Cultural and biological perspectives on gender and desire. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2001;12:33–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, - Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:242–255. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Striepe MI, Harmon T. Gender matters: Constructing a model of adolescent sexual health. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:4–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552162. doi:10.1080/00224490309552162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruggen LK, Runtz MG, Kadlec H. Sexual revictimization: The role of sexual self-esteem and dysfunctional sexual behaviors. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:131–145. doi: 10.1177/1077559505285780. doi:10.1177/1077559505285780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, Lefkowitz ES, Maggs JL. Short-term positive and negative consequences of sex based on daily reports among college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:558–569. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.589101. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.589101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, Maas MK, Lefkowitz ES. “It felt good but weird at the same time”: Emerging adults’ feelings about their first experiences of six different sexual behaviors. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0743558414561298. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW. The truth must be in here somewhere: Examining the gender discrepancy in self-reported lifetime number of sex partners. Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:375–386. doi: 10.1080/00224499709551905. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Gender and reproductive rights, glossary, sexual health. 2006 Retrieved July 11, 2012, from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/gender/glossary.html.