Abstract

Purpose

This manuscript will describe institutional changes observed through goal analysis that occurred following a multidisciplinary education project, aimed at preparing healthcare professionals to meet the needs of the growing numbers of cancer survivors.

Method

Post course evaluations consisted of quantitative questionnaires and follow up on three goals created by each participating team, during the 3-day educational program. Evaluations were performed 6, 12 and 18 months-post course for percent of goal achievement. Goals were, a priori coded based on the Institute of Medicine’s survivorship care components, along with 2 additional codes related to program development and education.

Results

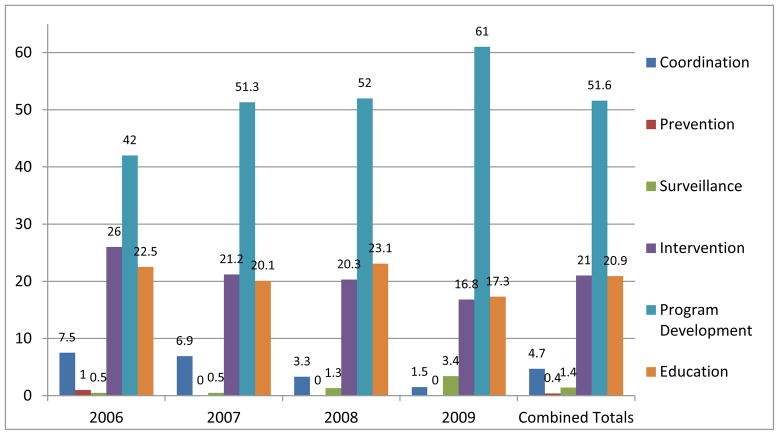

Two hundred and four teams participated over the 4 yearly courses. A total of 51.6% of goals were related to program development, 21% to survivorship care interventions, 20.9% on educational goals, and only 4.7% related to coordination of care, 1.4% on surveillance, and 0.4% related to prevention-focused goals. Quantitative measures post course showed significant changes in comfort and effectiveness in survivorship care in the participating institutions.

Conclusion

During the period 2006–2009, healthcare institutions focused on developing survivorship care programs and educating staff, in an effort to prepare colleagues to provide and coordinate survivorship care, in cancer settings across the country.

Implications

Goal-directed education provided insight into survivorship activities occurring across the nation. Researchers were able to identify survivorship care programs and activities, as well as the barriers to developing these programs. This presented opportunities to discuss possible interventions to improve follow-up care and survivors’ quality of life.

Keywords: Cancer Survivors, goal-directed care, nursing education, self-reported practice changes, integration of care

Introduction

Cancer survivors are increasing annually, with an expected 13.7 million Americans alive today, who have a history of cancer [1]. This population ranges from people who will be cancer-free for the rest of their lives, to those living with cancer continuously without a disease-free period [1]. Healthcare for this group includes treatment for patients with active disease, as well as management of long-term and late effects for those who are cancer-free.

While a cancer patient may be considered a survivor from the time of diagnosis on [2], cancer survivorship healthcare has concentrated on patients who have finished active treatment [3]. The healthcare delivery system must change, in order to provide follow-up care for cancer survivors, whose long-term treatment effects include physical effects (e.g., lymphedema), psychological concerns (e.g., fear of recurrence), social changes (e.g., loss of job), and spiritual challenges (e.g., meaning of life post-treatment). [4–6] Because this population’s needs span a broad spectrum, survivorship care is frequently shared between the oncology and primary care setting [3]. Changes in our healthcare settings and promoting a shared care model are critical to the successful integration and delivery of survivorship care [7].

Institution and setting changes are not easy; in fact, they can take years to complete [8]. The starting point for change, however, can be at least one or a small group of professionals from an institution learning what is needed for quality survivorship care – and that begins with education [9]. This article describes the content and evaluation of a national program on cancer survivorship care for health care providers and administrators. As Ferris et al [10](2001) indicate, knowledge alone is insufficient to produce change. The acquisition of skills necessary to facilitate institutional change is critical. Such skill development generally requires mentoring or individual support, in order for implementation to occur. This article addresses these concerns. Goal analysis will be discussed in this presentation and will include changes that have occurred in survivorship care across the nation.

Course Description

The National Cancer Institute funded this project, allowing for four annual multidisciplinary courses on improving quality of care for cancer survivors. The details of this course content, while published previously, will be summarized here [11].

A two- and a half-day course was held annually from 2006–2009. The curriculum was built around the City of Hope-Cancer Survivors’ Quality of Life Model, covering the four dimensions of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well being [12]. Content included the components of survivorship care as described in the Institute of Medicine Report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor – Lost in Transition(3). These components include Communication, Prevention/Detection, Surveillance, and Interventions [3]. A condensed agenda for the course illustrates the curriculum content and expert faculty who taught the courses (Figure 1). Teaching methods were based on adult learning principles and involved lectures, discussions, small group sessions, videos, resources, and refinement of individual goals for post-course implementation [13]. Using a mixed methods approach, qualitative and quantitative data were collected at baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months post course.

Figure 1.

Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care Agenda Components and Faculty

Participants were competitively selected from cancer settings across the country. Each setting submitted a team of two professionals, with the first member being a physician, nurse, administrator, or social worker, defined as Tier 1; and the second could be any other staff member involved in or targeted for involvement in survivorship care, defined as Tier 2. Applications required applicant statements on his or her interest in survivorship care, identification of past involvement in survivorship care, letters of support from an immediate supervisor and an administrator, and 3 goals aimed at creating and/or improving survivorship care in their health care setting after course completion.

Evaluation Methods

Application and Questionnaires

Team and setting demographics and characteristics were identified from the applications of accepted participants. Title and professional background as well as type of setting, size, and ethnicity of the population served, and baseline support services provided were reported for all team members.

Following course acceptance, participants submitted a setting survey and an institutional assessment as baseline data. The setting survey focused on the staff and administration and their comfort and commitment to survivorship care and was rated on a 0–10 scale where 0 was not comfortable to 10 equaling extremely comfortable. The institutional assessment focused on seven domains related to survivorship care, these included: Vision and management, Practice standards, Psychological and Social policies, Communication, Quality improvement, Patient and family education and Community network. Each statement was rated as present or not present to evaluate if change occurred over the follow up period. These were reevaluated at 6, 12 and 18 months post course.

The program evaluation was conducted immediately post-course with an assessment of the course content and faculty. Faculty provided evaluations as well and course content was revised yearly based on the faculty and participant evaluations.

Goal Development and Analysis

Goals, submitted in the course application, were used to evaluate changes that occurred in the participants’ institutions following course completion. These goals were refined during the course, as teams gained a better understanding of what survivorship care entails, and as they contemplated their institution’s needs and resources.

Goal development was an integrated component of the curriculum. Throughout the course, time was allotted to break into small groups with 3 to 4 teams and one faculty member to refine goals based on newly acquired course information. Using the S. M. A. R. T. Goal/Objective template, teams were taught to develop goals that were: Specific, Measurable, Attainable/Achievable, Relevant and Time Bound [14]. At the end of the course, participants kept a copy of their three refined goals, and a copy was provided to the survivorship staff for post course follow up.

Classification of the goals across settings included directed content analysis of the goals, using a priori codes based on the four survivorship care components identified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report [3]. Goals focused on coordination of care addressed the need for communication and collaboration between the survivor, the oncologist, and other healthcare providers. These goals included developing and delivering treatment summaries and survivorship care plans to specific survivor groups (e.g., breast cancer survivors) and their physicians. Prevention and Detection goals focused on activities that targeted prevention of recurrence or new cancers and included the healthy living concepts of diet, exercise, tobacco cessation, and sun protection, as well as detection of new cancers. Surveillance goals included healthcare related to identifying any recurrence or late effects from the cancer or the cancer treatment. Finally, intervention goals identified services that addressed one or more late or long-term effects post-treatment and were organized within the four City of Hope quality of life dimensions (e.g., rehabilitation clinic for lymphedema, counseling for psychological concerns, contact with a social worker for work-related issues, access to spiritual counseling for any existential concerns). Classification into these four components was done by the study’s principal investigator and the project director, with each coding the goals separately followed by a comparison of results, and resolution of any differences. During goal analysis, two additional codes were created for goals that did not fit the four IOM survivorship care components: 1) a Program Development goal code such as hiring survivorship staff and finding space for survivorship activities and 2) an Education code that included any activity providing for patient, staff and community education on cancer survivorship care.

A goal achievement tool was emailed to each participant with their goals identified as 1, 2 and 3. The tool allowed them to document their perceived percent of achievement for each goal, and a narrative space for them to document changes and/or barriers encountered. This occurred prior to each planned follow up telephone interview. Setting assessments and surveys were also collected prior to that follow up call. A semi-structured telephone interview was completed by the project director throughout all 4 courses at 6, 12 and 18 months. Evaluation included the team’s estimate of the percentage of achievement of each goal (defined at <49%, 50–99%, 100%, and not started or lost to follow up). Telephone discussion also included any barriers encountered. The project director supported participants during the interviews by helping them address barriers, encouraging networking with fellow participants, and referring them to appropriate resources to encourage success.

Results

Across the four annual courses, 204 two-person teams attended, representing 46 states. Participants were predominantly female (95%), Caucasian, with American Indians, Asians, and African Americans representation. Only 4% were Hispanic. Nurses were participants in 133 teams (65%), when combining RNs, NPs and APNs. Administrators were the second highest number of participants, in 109 teams (53%). Social Workers were present in 64 teams (32%) and physicians in 35 teams (17%). In general, participants lacked previous survivorship care experience, and for many, their primary reason for attending was to gain knowledge to return to their institution and begin integrating survivorship care into their settings or individual practice.

Setting Characteristics

The teams came from a variety of healthcare settings. Community Cancer Centers were by far the most common 133, with some representation from academic centers 54 and pediatric centers 9. Four teams were from ambulatory care/physician office settings and 4 from free-standing cancer centers. As to ethnicity of the populations served by these institutions, results revealed that populations served across institutions, across course-years, represented 72% Caucasian, 12% African American, 10% Hispanic, 4% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 2% American Indian.

Team Characteristics

Teams included participants from both Tier 1 (Administrators, nurses, social workers, or physicians) and Tier 2 (other disciplines involved in survivorship care). Most teams were from Tier 1, either representing the same discipline (42 teams) or mixed disciplines (139 teams). (Table 1) Teams were comprised of a Tier 1 participant and a Tier 2 participant and included the following Tier 2 professionals: psychologists, chaplains, and a recreational therapist, an LPH, a naturopathic practitioner, a dietitian and a physician assistant. The largest cohort of participants consisted of nurses (150), followed by administrators (131), social workers (66), and physicians (36), others (12). Fifty-four of the participants who were identified as administrators were also registered nurses. By far, the largest discipline represented was nurses.

Table 1.

Team Characteristics - 2006–9

| TIER | COMPOSITION | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | SUBTOTAL | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1–same discipline | |||||||

| ADM/ADM | 5 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 22 | ||

| RN/RN | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 19 | ||

| MD/MD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| SW/SW | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Subtotals | 11 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 42 | ||

| Tier 1 mixed discipline | |||||||

| RN/ADM | 6 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 51 | ||

| RN/SW | 13 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 37 | ||

| ADM/SW | 6 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 19 | ||

| RN/MD | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 16 | ||

| ADM/MD | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | ||

| MD/SW | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Subtotals | 35 | 35 | 37 | 32 | 139 | ||

| Tier 1 and Tier 2 | |||||||

| RN/Psych | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | ||

| ADM/Psych | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| ADM/Chap | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| ADM/LPN | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| ADM/RT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| RN/CHAP | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| RN/Naturopath | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| SW/Chap | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| SW/Dietitian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| SW/PA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MD/Psych | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Subtotals | 6 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 23 | ||

| Total | All Teams | 52 | 50 | 52 | 50 | 204 |

Course, Faculty, and Goal Evaluation

Course and faculty evaluations were favorable across all courses and were reported previously [11]. Overall course score averages were measured on a 0 – 5 scale (0=Not at all to 5=extremely satisfied). The evaluation scores for Opinion of the Course ranged from 4.70 – 4.91. Was the information stimulating and thought provoking ranged from 4.79 – 4.91. Finally to what extent did the course meet the objectives and expectations ranged from 4.65 – 4.86. Setting surveys and institutional assessments showed increases in how receptive and how comfortable staff are in caring for and improving cancer survivorship care [11]. Goal analysis provided details of team activities planned to improve survivorship care in their individual settings. Goal achievement was conducted at 6, 12, and 18 months post course. Of the 204 institution teams, 187 (92%) provided feedback at 6 months, and 169 (83%) provided feedback at 12 and 18 months. From years 2006 – 2009, the most common category of feedback was Program Development at 51.6%. The second most common code was Intervention at 21%, with Staff Education a close 3rd at 20.9%. Within the Intervention code, assessment or surveys of survivors’ needs represented 9% of the total Intervention goals. Coordination goals were next common at 4.7%, followed by Surveillance 1.4% and Prevention/Detection 0.4%. The distribution of goal classification across the 4 years and combined totals shows a consistent pattern from 2006 to 2009 (Figure 2). Goal achievement was evaluated by asking participants at 6, 12 and18 months what percentages of their goals were implemented. Participants rated achievement as 100% complete, 99-50% complete, 49% or less complete, and not started or lost to follow-up care (Figure 3). Most goals at 18 months post-course were still in process, ranging from 50 to 99% complete. However, completed goals across the years ranged from 18% in 2006 to 15% in 2009 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Goal Classification and Totals at Course End 2006–2009

Figure 3.

2006–2009 Goal Achievement by 18 Months

Discussion

Participants in the multidisciplinary cancer survivorship courses from 2006 to 2009 represented a variety of disciplines, with as expected, the largest percentage of participants being administrators and nurses 131 (32%), 150 (37%) respectively. The potential for developing and sustaining survivorship programs is high with this combination, since administrators are involved in setting priorities in institutions and obtaining resources for those priorities, while nurses are the largest group of clinicians involved in the day-to-day care of cancer patients, across the trajectory of disease [15, 16]. In addition, 46 states across the continental United States were represented by course participants. Our aims for both discipline and geographic representation were met.

The curriculum was rated highly by both participants and faculty; in turn the faculties were rated highly by the participants. The curriculum content was developed around the four priority areas identified in the IOM report – Coordination, Prevention and Detection, Surveillance, and Interventions. A variety of resources were provided to assist participants in implementing and refining survivorship care within their own institutions. Each participant received a copy of the IOM report-From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor-Lost in Transition as well as the IOM video, Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, which describes cancer survivorship care and includes interviews with survivors, as well as professionals who participated in creating the IOM report [3]. This video is an excellent way to begin educating staff at healthcare settings about the need for and components of survivorship care. Many settings used the video as a way of introducing their physicians and administrators to what survivorship care is and the deficits currently faced by cancer survivors. Additional resources were provided to the participants including access to the slide presentations to use to develop educational programs they might plan for the future. Faculty allowed participants to contact them directly should they have specific questions as well as provided additional resources within their presentations on examples of assessment tools used in their settings or samples of brochures for their specific programs. An index of on-line resources from the City of Hope Pain/Palliative Care Resource site was also included which provides key survivorship manuscripts as well as treatment summaries and care plan templates, and needs assessment tools [17].

Program evaluation included documentation of institutional changes in policies or survivorship activities occurring in each setting as documented between baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months post course. Institutional or setting changes in attitudes and comfort of staff across the 18 months, institutional policy changes and mission statements were changed post the course. These data are described in detail in another publication. [11].

The goals followed the S.M.A.R.T. format that helped to keep the goals achievable in relation to timeframe and content. [14]. Goal analysis revealed where settings were focusing their survivorship activities. During 2006–2009 survivorship was finally being recognized as an important part of providing quality cancer care. This was a development stage in most institutions, and activities were focused on garnering institutional resources and defining planned models for providing survivorship care related to the individual settings[18].

The highest numbers of goals were related to program development 51%, defined as activities necessary to establish a program, included identifying a survivorship team or champion, building administrative support, and evaluating current resources or activities. An example of this type of goal was: “within 6 months we will implement a nurse navigator role in the breast center to help financial/social/spiritual assessment of survivorship concerns”. Establishing a new program or standard of care within the 204 participating settings required individual analysis of resources including staff support and survivors’ identified needs.

The second most common theme for goals were Educational, including education for staff, patient, caregivers and public (22%). Examples of goals in this area reflected the need to bring the rest of the staff at individual health care settings up to date on cancer survivorship care. An example of this goal was: “within 6 months provide 30 professional staff with survivorship education through in-service trainings”. Using resources provided at the course was a common approach to accomplishing these goals. The third highest themes for goals were related to intervention goals (21%). In this area goals focused on development of resources needed to address late and long term effects of cancer survivorship. Some participants surveyed patient populations to identify most common needs and concerns so that resources for survivorship care could address the most pressing needs of the institution’s cancer populations. Additional goals on Intervention included developing support groups, organizing a lymphedema clinic, providing community resources for social and psychological support, and planning annual educational events for all survivors. An example of this type of goal was: “By January we will open a monthly long term follow up/chronic graft vs. host disease clinic”.

Coordination goals, which reflected the development of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans for distribution to patients and their primary care physicians, only represented a very small proportion of the goals 13%. An example of this goal type was “we will implement survivorship care plans with breast cancer population, 100% of appropriate patients will receive by June”.

Providing survivorship care plans and treatment summaries is probably the most labor intensive intervention – requiring personnel to populate a treatment summary from a thorough review of the medical record, and then develop a disease-specific care plan. During the years during which these courses were being held, templates for these documents were few and lengthy and specific disease guidelines had not been published. Currently disease-specific survivorship guidelines have been published by a number of organizations, and can be used to facilitate the development of care plans within institutions [19, 20].

Goal achievement was evaluated by each team based on their % of achievement analysis using a documentation tool. This allowed them to update in narrative form any changes they had made as well as provide the % of achievement at 6, 12 and 18 months post course. By 18 months, the vast majority of teams reported that their goals were still in process. However, for 2006 45%, 2007 47%, 2008 38% and 2009 42% of the goals were 100% achieved, illustrating that despite other ongoing institutional priorities, goals of developing and sustaining survivorship care were being accomplished in many of the participating institutions. Nonetheless, up to 3% of the goals were either never started, or information on them was lost to follow-up. One can speculate that the barriers described by other teams contributed to the lack of follow up for these settings. Competing projects within an institution such as building Electronic Medical Records, beginning psychosocial screening programs, and dealing with staff turnover may have taken priority. In fact, 20% of the participant teams were no longer intact at 18 months because of changes in team members’ responsibilities or because participants left the institution. In addition, 5 participant teams never responded to our follow-up evaluation, despite initial commitment to do so and confirming administrative letters that accompanied their application.

Study limitations related to goal analysis included the lack of resources to gather achievement percentages from other sources within the settings. It was impossible to verify that the goals had been achieved. Additionally follow up after the 18 months would be important to describe the sustainability of programs over time. There were no comparisons made between settings or reasons to think participants needed to exaggerate their activities. Interviews over the 18 months allowed for a relationship of supporter and mentor to be provided. Participants would email freely to the project director, faculty and other participants to gather resources and problem solve whenever possible.

We completed four annual courses and provided survivorship education to 204 teams from cancer settings across the nation. The question remains whether or not staff education does, in fact, lead to practice changes. Most reports on the value of professional education assume that an increase in knowledge and confidence will lead to changes in clinical practice [21]. Evidence to support this is scant, and consists primarily of mailed questionnaires, focus groups, and qualitative interviews asking participants about their perceptions related to the impact of education on their practice [21]. Perceived competence is important and we did find post course that participants who felt baseline that their knowledge of survivorship care was limited realized by the end of the 18 months that they did have an understanding and the competence to provide that care. We think that our approach of including both quantitative questionnaires and semi structured qualitative telephone interviews along with goal achievement provides evidence of the impact of education on changes in practice. As one of our participants related in her conference call with the project director, “you keep our feet to the fire.”

In summary, institutional change is challenging. The changes that the majority of our course participants made are important in developing care for cancer survivors in a variety of healthcare settings across the country. Encouraging goal directed care provides a method of establishing the plans for a setting and the ability to measure their achievements at least against themselves. While this is only the initial wave of developing survivorship programs, it is a beginning, and the provision of needed, quality care for cancer survivors is increasing.

Implications for future research

The need for research in cancer survivorship care continues, including a focus on physical structures and models as well as interventional studies to provide and improve care and minimize side effects are needed [22]. We feel strongly that improving knowledge through comprehensive education is an essential first step. When participating teams enlist their institutions’ support and thus have direction and financial backing for services and staff essential for sustaining survivorship care, we improve the odds for developing and sustaining quality survivorship care. This program has provided evidence on what survivorship activities are occurring around the nation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NCI-R25 CA 107109

Footnotes

Ethical approval: For this type of study formal consent is not required.

There are no Conflicts of Interest for this manuscript.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. ACS The Official Sponsor of Birthdays Celebrates national Cancer Survivors Day. 2009 [cited 2010 November 1, 2010]; Available from: http://relay.acsevents.org/site/PageServer?pagename=RFL_FY10_OH_Power_of_Purple_0610#Survivorshttp://relay.acsevents.org/site/PageServer?pagename=RFL_FY10_OH_Power_of_Purple_0610#SurvivorsAmerican.

- 2.NCCS. National Coalition of Cancer Survivors (NCCS) Available from: www.canceradvocacy.org.

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Institute of Medicine [IOM] From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor-Lost in Transition. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2006. pp. 9–186. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brearley SG, et al. The physical and practical problems experienced by cancer survivors: a rapid review and synthesis of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(3):204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ness S, et al. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):35–42. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(3):241–51. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe MS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):631–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krugman M, Smith K, Goode CJ. A clinical advancement program: evaluating 10 years of progressive change. J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(5):215–25. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lester JL, Wessels AL, Jung Y. Oncology nurses’ knowledge of survivorship care planning: the need for education. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(2):E35–43. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.E35-E43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferris FD, von Gunten CF, Emanuel LL. Knowledge: insufficient for change. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(2):145–7. doi: 10.1089/109662101750290164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant M, et al. Educating health care professionals to provide institutional changes in cancer survivorship care. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(2):226–32. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0314-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(6):523–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles MS. A Neglected Species. 4e. Houston: Gulf Publishing; 1973; 1990. The Adult Learner. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neill J, Conzemius A, Commodore C, Pulsfus C. The Power of SMART Goals-Using goals to improve student learning. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gates P, Krishnasamy M. Nurse-Led Survivorship Care. Cancer Forum. 2009;33(3):176–179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Needleman J, et al. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(22):1715–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center. Survivorship 3/23/09. Available from: http://prc.coh.org.

- 18.McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(3):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network-Guidelines. [cited 2012 February 22, 2012]; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 20.ASCO. Clincal Practice Guidelines: Practice Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyatt DE. The impact of oncology education on practice--a literature review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(3):255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCabe MS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: Achieving High-Quality Cancer Survivorship Care. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]