Abstract

Limited health literacy has been shown to contribute to poor health, including poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in people living with HIV/AIDS, over and above other indicators of social disadvantage and poverty. Given the mixed results of previous interventions for people with HIV and low health literacy, investigating possible targets for improved adherence is warranted. The present study aims to identify the correlates of optimal and suboptimal outcomes among participants of a recent skills-based medication adherence intervention (Kalichman et al., 2013). Participants included in this secondary analysis were 188 men and women living with HIV who had low health literacy as determined by scoring ≤90% on a test of health literacy and had complete viral load data for baseline and follow-up. Participants completed physical, psychosocial and literacy measures using computerized interviews. Adherence was assessed by unannounced pill count and follow-up viral loads were assessed by blood draw. Results showed that higher levels of health literacy and lower levels of alcohol use were the strongest predictors of achieving HIV viral load optimal outcomes. The interplay between lower health literacy and alcohol use on adherence should be the focus of future research.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Medication Adherence, Health literacy

The HIV epidemic in the United States is closely associated with poverty.1 HIV is concentrated among the most socially disadvantaged and marginalized populations including impoverished individuals with low levels of education. Disadvantaged social position and lack of environmental resources (i.e. access to quality education, social capital, income equality, etc.) can impede access to quality health care as well as interfere with adherence to medical treatments and other health-related behaviors.

One of the direct results of low social position and lack of environmental resources is a potential increase in low health literacy among people living with HIV.2 Health literacy is an individual’s ability to access, process, and utilize health-related information with the end goal of informing and improving health-related decisions, health behaviors and clinical outcomes.2 Among a group that already experiences health disparities, people living with HIV who have limited health literacy skills are at an even further disadvantage in achieving optimal treatment outcomes for their HIV infection.

Individuals challenged by poor literacy skills are at risk for multiple adverse heath conditions including HIV infection.1,3–4 Additionally, low health literacy among people living with HIV has been associated with being less knowledgeable about HIV disease-related information.5 People living with HIV and low health literacy are more likely to misunderstand medication instructions leading to possible missed doses.6 Several studies have shown a robust relationship between poor antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and limited reading ability as well as poornumerical literacy.7–8 Further complicating the relationship between literacy and health, individuals with low literacy may also have overlapping cognitive deficits that further challenge medication adherence.9–10 Although low literacy is only one facet in a constellation of poverty indicators, studies have shown low health literacy predicts poor health, including poor ART adherence, over and above other poverty indicators including lower education.7,11–12 For all of these reasons, it is imperative to focus on those with low health literacy in order to optimize access and adherence to ART to ultimately reduce HIV-related disparities.

Only a few interventions have targeted improving ART adherence among people living with HIV who have limited health literacy. In one study, a 3–5 session intervention aimed at providing educational and psychological support to low literacy patients, conducted in Morocco, showed no significant change in adherence, although there was a significant increase in CD4 T-cell counts and improved HIV suppression.13 In Los Angeles, a small-scale randomized controlled trial was conducted to test an adherence enhancement program for low-income people living with HIV assumed to have lower health literacy.14 This intervention consisted of small group sessions and one-on-one counseling to increase participants’ knowledge and communication skills. Results indicated limited evidence for improved patient-provider relationships and no significant improvements in medication adherence. Recently, Kalichman and colleagues15 conducted a randomized controlled trial that included two skills-based adherence counseling interventions compared to a general health educational control condition. The authors found that participants with moderate health literacy benefitted from both of the skills-based adherence counseling conditions. In contrast, individuals with lower health literacy did not benefit from either skills-based adherence counseling condition.

Given the mixed results of medication adherence interventions for people living with HIV and low health literacy, further analyses may clarify factors associated with achieving clinical benefits from skills-based adherence counseling. In the present study, we examine the outcomes of Kalichman et al.’s (2013) trial to determine the correlates of benefitting from skills-based adherence counseling to achieve HIV viral suppression, the optimal outcome of ART.15 Similar analyses have been successfully conducted in the areas of physical activity and HIV sexual risk reduction.16–17 However, we are not aware of any previous research examining correlates of optimal outcomes for ART adherence for people with low health literacy.

We hypothesized that physical health measures (i.e. HIV symptoms, CD4 T-cell count), mental health measures (i.e. substance use, depression, HIV-related shame, social support) and literacy measures (i.e. reading and numerical literacy) would predict achieving optimal adherence intervention outcomes (i.e. HIV RNA viral suppression). Individually, these measures have been shown to be strong predictors of ART adherence and are, therefore, candidates for predicting optimal counseling outcomes. Using multivariable analyses, we will test the independent effects of literacy on optimal intervention outcomes.

METHOD

The “Stick To It” Adherence Intervention Trial

The current study is a secondary analysis of the outcomes of an adherence intervention trial (for primary findings see Kalichman et al., 2013).15 The trial was conducted in Atlanta, Georgia, a city with a growing HIV epidemic.18 Participants were recruited from Atlanta-metro area AIDS services and community outreach as well as through word-of-mouth. Participants were all determined to have low health literacy (see below). Enrollment occurred between November 2008 and April 2011. Procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants.

The adherence intervention trial included three conditions including two skills-based adherence counseling conditions compared to a general health control condition. The counseling sessions were conducted at a community-based research site. The skills-based adherence counseling conditions were grounded in Social-Cognitive Theory19–20 and designed for use in HIV treatment settings. All counseling was delivered in two 60-minute one-on-one sessions over two weeks and an additional 30-minute booster session two weeks later. The same interventionists delivered all of the counseling sessions for each condition.

Pictographic Adherence Counseling Condition

This counseling condition was tailored for people with lower health literacy skills and was delivered with a strong emphasis on pictographic illustrations of key concepts and relied on minimal reading. This counseling condition was designed introduce new adherence skills and to reinforce skills that the participants already utilized. Specifically, key activities within the counseling sessions were planning how to incorporate medication regimens into daily life, problem-solving skills, and role-play with particularly problematic scenarios. Strategies such as using a pillbox and setting up cell phone or alarm clock reminders were introduced. Self-monitoring skills for changes in adherence and viral load were also introduced and reinforced throughout the course of the intervention. Motivational enhancement techniques, such as providing direct feedback on participant health status was another important component of the intervention

Standard Adherence Counseling Condition

Counseling in the standard adherence counseling condition was the same as the pictographic adherence counseling condition, however, this counseling was not specifically tailored for people living with HIV and lower health literacy skills. Many of the materials included written descriptions of the concepts and skills presented.

General Health Information Control Condition

The control arm was contact-matched and focused on health improvement for people living with HIV. Counseling focused on the importance of maintaining healthy diets and exercise regimens as well as stress reduction. The counselor and participant worked through potential barriers and problem solved these scenarios. Participants who received the general health condition are not included in this secondary analysis.

Current Analysis

The current study is a secondary analysis of the “Stick To It” adherence intervention trial. The primary aim of this analysis is to ascertain the factors that significantly predict participants achieving optimal and suboptimal outcomes.

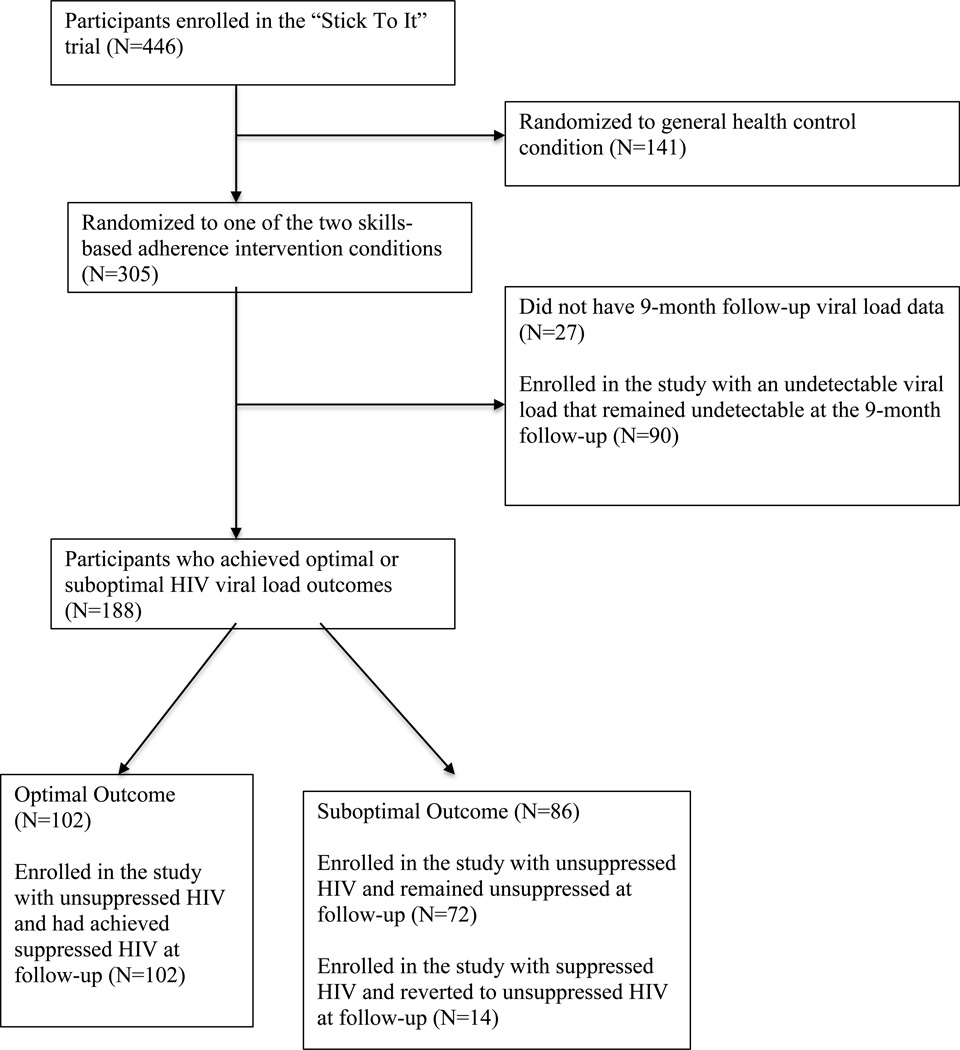

Figure 1 shows a flow chart for outcome determination in this study. Only participants randomized to receive the two skills-based adherence counseling interventions were included in this secondary analysis. Because these two conditions were indistinguishable in the primary outcome analysis, we collapsed the two conditions for this analysis.15 In order to calculate changes in HIV RNA, participants had to have complete data at baseline and 9-month follow-up. Viral load was based on chart abstraction at baseline and blood draw at the 9-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the determination of optimal outcome groups.

Optimal outcomes from ART adherence are achieved by suppressing HIV RNA (i.e. viral load). Viral suppression is defined as less than 50 copies/mL. The intervention trial found 102 participants achieved viral suppression post-intervention. A suboptimal outcome was defined as participants either (a) having HIV that remained unsuppressed from baseline to the follow-up or (b) having suppressed HIV at baseline that reverted to unsuppressed HIV at follow-up. Eighty-six participants fell into this category. Participants who were enrolled in the study with viral suppression at baseline that remained suppressed at follow-up were excluded from this analysis.

Measures

Reading and numerical literacy

To test reading literacy, participants completed the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA).21 This test is timed and includes 50 multiple-choice items, in which participants select the correct word (out of four options) to complete sentences from standard medical instructions. Scores range from 0 to 50 and percentages were computed for the total score. Because the intervention was targeted toward individuals with limited health literacy, participants had to score a 90% or below on the TOFHLA to be eligible for enrollment. The TOFHLA Numeracy Scale was also administered which assesses numerical reasoning for medical instructions.22 Scores ranged from 0–7.

Computerized interviews

Upon enrollment into the Stick To It adherence intervention trial, all participants completed intake measures including demographic information (gender, race/ethnicity, age, income, employment status, education) via audio-computer self-interview (ACASI). Additionally, participants completed a variety of measures focused on health and psychosocial variables that previous research has shown to predict ART adherence.23–24

HIV symptoms. The number of HIV symptoms experienced by participants was assessed by a 14-item scale.25 We calculated a composite using the summation of all 14 symptoms, alpha = 0.70. HIV-related shame. HIV-related shame is a negative affective response to one’s own experience living with HIV, which has been associated with reduced quality of life even when accounting for HIV symptoms, social support and perceived stress.26 To assess levels of shame, participants completed the reliable and valid HIV-related shame subscale of the HIV and Abuse Related Shame Inventory [HARSI].27 Participants were asked about thoughts and feelings over the past three months, responses were 0 = not at all, 1= a little bit, 2 = quite a bit and 3 = very much, alpha = 0.67. Depression symptoms. The Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD) was used to assess emotional distress.28 Participants completed the full 20-item CESD, alpha = 0.87. Items focused on how often a participant had specific thoughts, feelings and behaviors in the last seven days. Responses were 0 = 0 days, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, 3= 5–7 days. Scores range from 0 to 60 and scores greater than 16 indicate possible depression.

Social support. Level of social support was assessed through a14-item scale of tangible, emotional, and informational support.29 Responses were 1 = completely true, 2 mostly true, 3 = mostly false and 4 = completely false. Possible scores ranged from 14–56, with higher scores indicating more social support, alpha = 0.80. Stress. To assess levels of stress, participants completed 17 items focusing on the past three months.30 Participants indicated whether or not each specific event had occurred within the past three months. Composite scores ranged from 0 to 17, alpha = 0.74. Alcohol use. To assess level of alcohol use, participants completed the AUDIT-C, which has been found valid in various populations.31 In our sample, it had acceptable internal consistency (alpha = 0.77).

HIV RNA viral load and CD4 T-cell counts

Participants were asked to obtain their latest viral load and CD4 T-cell counts from their health care provider at baseline. These records could not be older than three months. If a participant was unable to obtain current reports from their health care provider (less than 5%), their blood was drawn by a certified phlebotomist. Health care providers and blood assays use several cut-offs to determine undetectable viral load. For consistency across chart abstracted viral load values, we defined undetectable viral load as <50 copies/mL.

To assess HIV RNA viral load at the 9-month final follow-up, participants provided blood specimens. Blood samples were provided at the project office using standard phlebotomy. Whole blood specimens in EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson) were centrifuged at 500g for 10 minutes within 4 hours of collection. Undetectable viral load was defined as <50 copies/mL.

ART adherence

Medication adherence was assessed monthly for the duration of the study using telephone-based unannounced pill counts.32 Adapted from home-based procedures,33 telephone-based unannounced pill counts have been shown to be reliable and valid.32 Following an in-office training session, an adherence assessor called participants each month on their study-provided cell phones to count their pills. The assessor asked the participant to count the number of pills in each bottle aloud twice. Using information from the medication bottles (e.g. prescription number, dispense date, dispense amount and dosage information) the assessor calculated adherence for each medication. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of the number of pills taken between phone calls relative to the number of pills prescribed for that period of time.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were structured to test for factors associated with optimal/suboptimal outcome groups. Bivariate logistic regressions were conducted for adherence at each month throughout the study to test optimal outcomes in relation to clinically relevant categories of adherence (cut-off of 85%). Bivariate logistic regression models were also conducted to determine associations between achieving an optimal outcome and physical health, psychosocial characteristics, substance use and literacy. Bivariate associations that were significant at the p<0.10 level were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Significant physical health variables were omitted from the multivariate logistic regression in order to avoid conflating the predictors with the optimal health outcome. Significance in the multivariate analysis was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Adherence in Relation to Optimal Outcomes

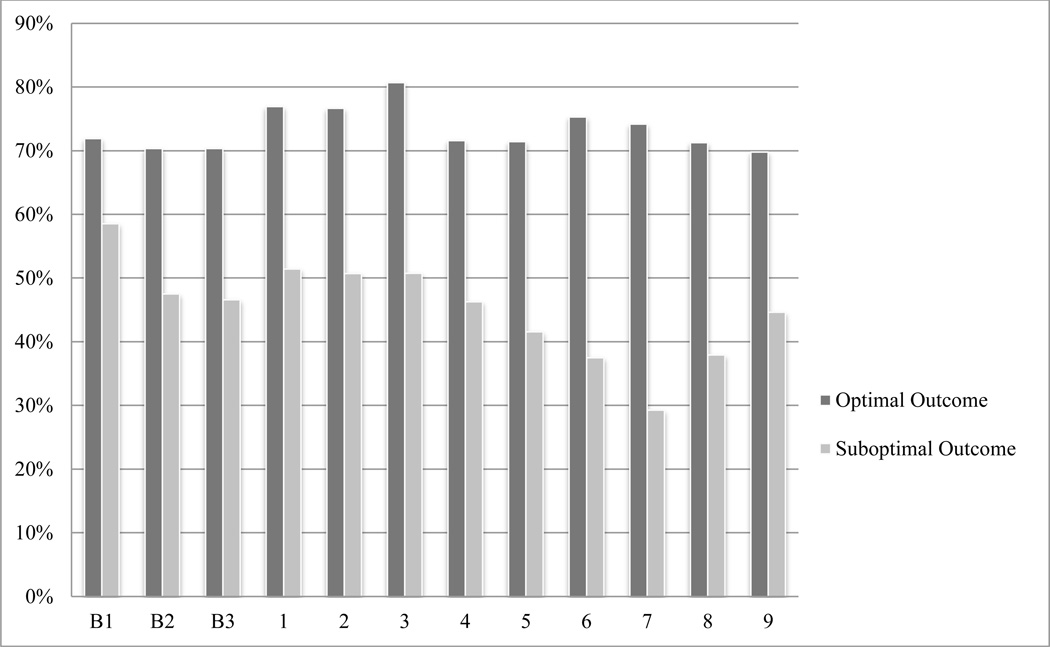

Figure 2 summarizes the findings for adherence differences among groups defined by outcomes. Results show that across all months except for one (Baseline 1), high adherence was significantly associated with achieving an optimal HIV suppression outcome.

Figure 2.

Percent of participants who achieved 85% of higher adherence by trial outcome.

Note: B= baseline, Odds Ratios: B1 1.81; B2 2.76**; B3 2.98**;

Time 1 (T1) 3.06**; T2 3.26**; T3 3.82**; T4 3.05**; T5 4.22**; T6 4.95**; T7 6.75**; T8 3.99**;

T9 3.10**; **p<.01

Predictors of Optimal Outcomes

Table 1 shows the associations between achieving optimal outcomes and demographic characteristics. The only demographic characteristic that predicted optimal outcomes was gender; women were twice as likely to achieve optimal outcomes than men. Years of education and income level did not significantly predict achieving an optimal outcome. Table 2 shows associations between achieving optimal outcomes and physical health, mental health, substance use and literacy. Participant’s reading literacy scores were significantly related to outcomes such that scoring below 85% was related to failing to achieve optimal outcomes. Participants who had been living with HIV for a shorter amount of time and those with higher CD4 T-cell counts at baseline were also more likely to achieve an optimal outcome. Finally, experiencing less stress and using less alcohol were associated with achieving optimal outcomes.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants who achieved an optimal outcome and those who did not.

| Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal (N=102) | Suboptimal (N= 86) | Unadjusted OR |

|||

| Participant Characteristics | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male (indicator) | 65 | 64 | 67 | 78 | |

| Female | 37 | 36 | 19 | 22 | 2.007* |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White (indicator) | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| African American/Black | 94 | 92 | 83 | 97 | 0.378 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.333 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - - - |

| Income | |||||

| $0 – $10,000 (indicator) | 76 | 75 | 61 | 71 | |

| $11,000 – $20,000 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 1.246 |

| $21,000 – $30,000 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 0.941 |

| Over $30,000 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.33 |

| Employment Status | |||||

| Unemployed (indicator) | 38 | 37 | 30 | 35 | |

| Working | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 1.053 |

| On Disability | 54 | 53 | 46 | 53 | 0.927 |

| Student | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - - - |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0.197 |

| M | SD | M | SD | OR | |

| Age | 45.4 | 7.4 | 45.2 | 7.1 | 1.005 |

| Years of Education | 11.74 | 1.84 | 11.87 | 1.99 | 0.963 |

p<.05

Note: - - - indicates OR not calculated due to small N’s

Table 2.

Physical health, mental health, substance use and cognitive functioning measures for participants who achieved an optimal outcome and those who did not.

| Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal (N=102) | Suboptimal (N= 86) | Unadjusted OR |

|||

| Correlates | N | % | N | % | |

| TOFHLA | |||||

| 85%–90% (indicator) | 53 | 52 | 32 | 37 | |

| <85% | 49 | 48 | 54 | 63 | 0.548* |

| M | SD | M | SD | OR | |

| Numeracy | 4.6 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 1.009 |

| Years Since Testing Positive | 12.3 | 8.1 | 14.8 | 7.4 | 0.960* |

| Baseline CD4 T-cell Count | 414.5 | 281.3 | 309.6 | 206.2 | 1.002** |

| HIV Symptoms | 3.9 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 0.961 |

| Shame | 9.3 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 3.9 | 1.003 |

| Cognitive-Affective Depression | 8.5 | 6.4 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 0.989 |

| Social Support | 28.4 | 7.2 | 27.9 | 7.2 | 1.011 |

| Stress | 4.6 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 0.905* |

| Alcohol use | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.826** |

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01

Multivariate Logistic Regression

In the multivariate model, participant gender and stress were no longer statistically significant predictors of achieving optimal outcomes (Table 3). However, health literacy remained significant such that those who scored in the moderate literacy range on the TOFHLA were twice as likely to achieve optimal viral suppression. Low alcohol use also remained a significant predictor of achieving a optimal outcome while controlling for the other variables.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression predicting optimal outcome

p<0.10,

p<0.05

DISCUSSION

This study identified predictors of achieving optimal clinical outcomes for people living with HIV and limited health literacy who received skills-based adherence counseling. Results are consistent with past research showing literacy is a robust predictor of medication non-adherence. The primary outcomes from this trial found a significant condition by literacy group interaction effect for both adherence and viral suppression outcomes.15 The current analysis extends the main trial findings by including psychosocial variables that were not previously accounted for in the main outcomes. Thus, even when important demographic and psychosocial characteristics are accounted for, health literacy remains a significant predictor of achieving optimal HIV treatment outcomes. Demographic characteristics most commonly associated with literacy, specifically years of education and income, did not independently predict achieving an optimal outcome. This finding parallels previous studies, showing that within an array of poverty markers there is a specific association between low health literacy and poor health outcomes.7,11

Alcohol use emerged as an independent predictor of failing to achieve optimal adherence counseling outcomes. This finding is also consistent with the literature regarding the relationship between ART adherence and alcohol use. Studies consistently show that drinkers miss more doses of ART than those who do not drink.34–36 Multiple cognitive, behavioral and social ramifications of alcohol use may contribute to the associations between alcohol use and non-adherence.37–38 While alcohol use is a known predictor of medication non-adherence, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between alcohol use and achieving optimal outcomes within an ART adherence counseling intervention.

There are several limitations of this study that should be considered. First, the measures of clinical outcomes may be limited. The calculation of outcome utilizes only two data points, thus, we are unable to describe patterns of change in viral suppression; the relationship between viral suppression at baseline and follow-up may not have been linear. Our measures of depression, stress, alcohol use, and other socially sensitive characteristics were assessed by self-report and may therefore have been influenced by social desirability. This study may also be limited by its demographics and location. This intervention was conducted in one southeastern U.S. city and the sample was mostly comprised of older, African American adults with lower incomes. It is possible that the findings within this study do not generalize to a broader population of people living with HIV. With these limits in mind, the current findings have implications for adherence interventions that target individuals with lower health literacy.

The classic models of individual-level behavior change that have been applied in ART adherence research do not directly address the issues that most closely predicted optimal health outcomes among persons with lower literacy. The robustness of the relationship between alcohol use and medication adherence has been demonstrated and the current analysis supports the need to intervene on alcohol use in order to achieve success in adherence interventions. There have been interventions conducted to reduce alcohol use to improve adherence, however, none has demonstrated clear evidence for improved adherence or health outcomes.39–40 More research is needed to maximize the efficacy of these types of trials to simultaneously reduce hazardous drinking behaviors and increase medication adherence. Furthermore, alcohol use may have specific effects among a low literacy population. For example, people with lower health literacy may have fewer reserve coping and adaptive life skills to compensate for alcohol use. The interplay between lower health literacy and alcohol use on adherence should be the focus of future interventions.

The disadvantages facing individuals with low health literacy may not only impact medication adherence but also patient-provider interactions and patient-pharmacist interactions, as well as the overall navigation of the health care system. Individuals with lower health literacy skills who drink alcohol can particularly benefit from increasing treatment services to reduce alcohol consumption. Additionally, empowering these individuals and training them in self-advocacy skills within the health care system may help to overcome these disadvantages. Individuals with lower literacy skills trained in patient self-advocacy may be able to optimize the care that they receive as well as increase their medication adherence. Research should test patient directed models of health improvement in people with lower health literacy skills.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identified two strong predictors of achieving optimal outcomes from skills-based adherence counseling for people living with HIV and limited health literacy. Individuals with moderate levels of health literacy were more likely achieve optimal clinical outcomes following the intervention. Conversely, individuals with high levels of alcohol use were significantly less likely to achieve an optimal outcome. Alcohol use may have specific effects among a low literacy population and the interplay between lower health literacy and alcohol use on adherence should be the focus of future research.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grants T32MH07487 and R01MH082633.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A Pandemic of the Poor: Social Disadvantage and the U.S. HIV Epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wawrzyniak AJ, Ownby RL, McCoy K, Waldrop-Valverde D. Health literacy: impact on the health of HIV-infected individuals. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirsch IS, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. [Accessed December 19, 2013]; Available at: nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93275.pdf.

- 4.Ladd H. Education and Poverty: Confronting the Evidence. J Policy Anal Manage. 2012;31(2):203–227. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Functional health literacy is associated with health status and health-related knowledge in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(4):337–344. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalichman SC, Pope H, White D, et al. Association between health literacy and HIV treatment adherence: further evidence from objectively measured medication adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2008;7(6):317–323. doi: 10.1177/1545109708328130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldrop-Valverde D, Osborn CY, Rodriguez A, Rothman RL, Kumar M, Jones DL. Numeracy skills explain racial differences in HIV medication management. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):799–806. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Applebaum AJ, Reilly LC, Gonzalez JS, Richardson MA, Leveroni CL, Safren SA. The impact of neuropsychological functioning on adherence to HAART in HIV-infected substance abuse patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(6):455–462. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldrop-Valverde D, Jones DL, Gould F, Kumar M, Ownby RL. Neurocognition, health-related reading literacy, and numeracy in medication management for HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(8):477–484. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):1027–1030. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarra AM, Neu N, Toussi S, Nelson J, Larson EL. Health literacy and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 25(3):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khachani I, Harmouche H, Ammouri W, et al. Impact of a Psychoeducative Intervention on Adherence to HAART among Low-Literacy Patients in a Resource-Limited Setting: The Case of an Arab Country – Morocco. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2012;11(1):47–56. doi: 10.1177/1545109710397891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.vanServellen G, Nyamathi A, Carpio F, et al. Effects of a treatment adherence enhancement program on health literacy, patient-provider relationships, and adherence to HAART among low-income HIV-positive Spanish-speaking Latinos. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19(11):745–759. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of HIV Treatment Adherence Counseling Interventions for People Living with HIV and Limited Health Adherence. J Acquir Immuno Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):42–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318286ce49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall PA, Zehr C, Paulitzki J, Rhodes R. Implementation of Intentions for Physical Activity Behavior in Older Adult Women: An Examination of Executive Function as a Moderator of Treatment Effects. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(1):130–136. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Sadicario JS, et al. Predictors and moderators of outcomes of HIV/STD sex risk reduction interventions in substance abuse treatment programs: a pooled analysis of two randomized controlled trials. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgia Department of Public Health. HIV/AIDS Surveillance, Georgia, 2012. [Accessed: December 19, 2013];2013 Sep; Available at: http://dph.georgia.gov/data-fact-sheet-summaries.

- 19.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self-efficacy in Changing Societies. Vol. 334. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA): a new instrument for measuring patient’s literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–542. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malow R, Dévieux JG, Stein JA, et al. Depression, substance abuse and other contextual predictors to antiretroviral therapy among Haitians. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1221–1230. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellins CA, Kang E, Leu CS, Havens JF, Chesney MA. Longitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(8):407–416. doi: 10.1089/108729103322277420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(10):662–670. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persons E, Kershaw T, Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB. The impact of shame on health-related quality of life among HIV-positive adults with a history of childhood sexual abuse. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(9):571–580. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neufeld SA, Sikkema KJ, Lee RS, Kochman A, Hansen NB. The development and psychometric properties of the HIV and Abuse Related Shame Inventory (HARSI) AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):10063–10074. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brock D, Sarason I, Sarason B, Pierce G. Simultaneous assessment of perceived global and relationship-specific support. J Soc Pers Relat. 1996;13:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leserman J, Jackson ED, Petitto JM, et al. Progression to AIDS: the effects of stress, depressive symptoms, and social support. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(3):397–406. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):781–787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0594-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Cherry C, et al. Monitoring medication adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9(5):298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Chesney M, Moss A. Comparing Objective Measures of Adherence to HIV Antiretroviral Therapy: Electronic Medication Monitors and Unannounced Pill Counts. AIDS Behav. 2001;5(3):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, Roberts MS, et al. Estimating the impact of alcohol consumption on survival for HIV+ individuals. AIDS Care. 2007;19:459–466. doi: 10.1080/09540120601095734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigilaro J, et al. A temporal dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171937.87731.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Freedberg KA, Palepu A. Alcohol consumption and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. Alcohol ClinExp Res. 2004;28(4):572–577. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122103.74491.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, et al. Intentional non-adherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):399–405. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, et al. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;23(6):511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, Holder C. Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):443–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to enhance antiretroviral therapy adherence in patients with a history of alcohol problems. Antivir Ther. 2005;10(1):83–93. doi: 10.1177/135965350501000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]