Abstract

The ability to reprogram adult somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells that can differentiate into all three germ layers of the developing human has fundamentally changed the landscape of biomedical research. For a neurodegenerative disease like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), which does not manifest itself until adulthood and is a heterogeneous disease with few animal models, this technology may be particularly important. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) have been created from patients with several familial forms of ALS as well as some sporadic forms of ALS. These cells have been differentiated into ALS-relevant cell subtypes including motor neurons and astrocytes, among others. ALS-relevant pathologies have also been identified in motor neurons from these cells and may provide a window into understanding disease mechanisms in vitro. Given that this is a relatively new field of research, numerous challenges remain before iPSC methodologies can fulfill their potential as tools for modeling ALS as well as providing a platform for the investigation of ALS therapeutics.

Keywords: stem cells, IPSC, motor neuron, astrocyte, non-cell autonomous, human

Introduction

In vitro strategies to recapitulate disease mechanisms causing Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) have been attempted for some time. Attempts to manipulate cell-types associated with the disease have included the study of primary dissociated motor neurons and glial cells from animal models, as well as other neural and non-neural cell lines. While many initial studies focused on motor neurons in culture, later work included the co-culture of non-neuronal cell types with motor neurons to allow for a dissection of individual cellular contributions to disease pathogenesis (Veyrat-Durebex et al., 2014).

Animal models of ALS have been generated to understand disease mechanisms as well as provide platforms for testing therapeutic strategies. The majority of ALS rodent models have been based on the use of transgenic overexpression of genes known to cause familial ALS. These have included the overexpression of mutations in the following genes: superoxide dismutase (SOD1), tar DNA protein 43 (TDP-43), fused in sarcoma (FUS), and valosin-containing protein (VCP). These in vivo models have taught us a great deal about the molecular cascades by which these specific genes may cause disease, the neural cell types that contribute to ALS pathogenesis, the complexities of genotype-phenotype correlations, and at least a window into using these animals for the study of therapeutics for ALS (McGoldrick et al., 2013). In part because animal models for understanding ALS disease mechanisms have demonstrated shortcomings with regard to recapitulating sporadic ALS and also have had limited capacity for predicting therapeutic efficacy of compounds in ALS, investigators have been seeking alternatives for addressing both issues (Benatar, 2007).

However, modeling ALS using rodents with ALS carrying disease causing mutations only represents a subset of the disease as a whole. Furthermore, as a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease, modeling ALS using animal models also requires months of study, which results in an increase in study costs. In light of these limitations, the research community has shown great interest in the potential value of modeling ALS using induced pluripotent stem cells. These cells also have the advantage of being derived from humans, could be derived from ALS patients with both familial and sporadic forms, and could be versatile in allowing investigators to differentiate these cells into multiple cell subtypes.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) were first characterized by Yamanaka and colleagues in 2006 with their reprogramming from mouse somatic cells (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). This breakthrough was followed by the development of human iPSC in 2007 (Takahashi et al., 2007). Yamanaka and colleagues used cultured skin fibroblasts from adult individuals. Using four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4) introduced via retroviral constructs, they reprogrammed these fibroblasts and demonstrated that the resulting cells had the capacity for self renewal, could differentiate into all three of the embryonic germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm), and form teratomas following introduction into rodent hosts. The development of this technology has resulted in a fundamental change in the uses of stem cells for disease modeling and circumvented the ethical concerns regarding the use of embryonic stem cells (ESC). This work resulted in his being awarding a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012. (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2012/yamanaka-facts.html)

With the development of induced pluripotent stem cell methodologies came the opportunity to potentially investigate mechanisms of human ALS in vitro. IPSC can be differentiated into neural subtypes including neurons, motor neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells, and myoblasts among others. However, just as important as differentiating cells into these subtypes is that this technology allows us the first opportunity to develop cell subtypes from ALS patients with known genotypes and phenotypes. This was previously not feasible using embryonic stem cells since those cells would have to be derived from embryonic tissue prior to the manifestation of disease. While the use of ESC could be made from embryos known to harbor penetrant ALS gene mutations, there was no potential for using ESC to model sporadic ALS. In addition, the affected tissue (brain and spinal cord) from patients is not accessible for extensive in vitro research. Therefore, the use of iPSC may allow a more thorough study of the neurodegeneration process.

Human iPSC differentiation into neural subtypes and functional elements of the motor unit

While iPSC can generate neural subtypes, questions remain as to how well in vitro characterization of these cells recapitulates in vivo biology and, ultimately, the fidelity of the neurodegenerative disease process seen in ALS. Nevertheless, the field of in vitro disease modeling using iPSC is young and initial demonstrations of the capacity to faithfully differentiate iPSC into neurons, motor neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and other ALS-relevant cell subtypes has shown promise.

A central and ever-evolving theme in our understanding of ALS pathogenesis is the recognition that numerous cell types play a role in either disease pathogenesis (with motor neurons being a likely candidate) as well as disease progression (including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia). The contributions of these other cell types have been demonstrated to be relevant both in vitro and in vivo primarily using mice overexpressing the mutant SOD1 gene (Ilieva et al., 2009; Papadeas et al., 2011). Therefore, the demonstration that human iPSC could be differentiated into ALS-relevant cell subtypes was considered important to this evolving field as it would allow investigators the opportunity to work with human cells, avoid the use of transgenic overexpression of mutant ALS genes, and allow for the investigation of numerous ALS gene mutations for which there are no known animal models.

Motor Neurons

Motor neurons had been previously generated from human embryonic stem cells (ESC) that allowed for modeling motor neuron diseases carrying specific gene mutations causing ALS (Li et al., 2005) (Di Giorgio et al., 2008; Marchetto et al., 2008). However, this method had limitations because genotype/phenotype correlations could not be tested in embryonically-derived cells and ESC could not be used for studying sporadic forms of motor neuron diseases like ALS. The demonstration that human iPSC could be differentiated into motor neurons came from Eggan and colleagues using fibroblasts obtained from an individual with familial ALS associated with an autosomal dominant SOD1L144F mutation (Dimos et al., 2008). At the time of the publication, the work was particularly thorough in demonstrating that the resulting iPSC (reprogrammed using Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 introduced into fibroblasts with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSVg)– pseudotyped Moloney-based retroviruses) were capable of producing each of three embryonic layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm). Using methods that had been previously reported (Wichterle et al., 2002) to differentiate ESC to motor neurons in rodent models, these investigators used a combination of an agonist of the sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway and retinoic acid (RA) to generate motor neurons as defined by the expression of the motor neuron transcription factor Hb9, with an efficiency of approximately 20%. This report set the stage for the future development of motor neurons from patients with ALS using similar protocols.

Amoroso and colleagues used a small molecule strategy to accelerate the differentiation of motor neurons over a 3 week period utilizing both human ESC and human iPSC. This strategy also resulted in a higher yield of motor neurons than previously noted by Dimos and colleagues. The resulting motor neurons had electrophysiological properties consistent with neuronal identity including the development of spontaneous calcium transients and action potential firing. They were also capable of projecting axons following their transplantation into the developing chick spinal cord. This work was not only important in advancing the methods for production of motor neurons but also this work went on to detail the motor neuron subtypes generated. Using these methods, the authors noted that the majority of neurons developed into limb-innervating motor column (LMC) motor neurons innervating limbs whereas previous protocols yielded medial motor column (MMC) neurons that innervate axial musculature (Amoroso et al., 2013).

The utilization of iPSC-derived motor neurons modeling ALS is discussed in greater detail in the section “ iPSC-derived Motor Neurons from ALS patients” below.

Astrocytes

Work by Krencic and colleagues in 2011 was critical in broadening the tools for ALS research by demonstrating that astrocytes could be generated from human ESC. It was particularly noteworthy that this group was able to also use chemically-defined media to generate astrocytes with regional identities and with functional properties including glutamate transport and ATP-dependent calcium wave propagation. In addition, they demonstrated that these cells were also involved in the promotion of synaptogenesis. They extended these in vitro observations with the transplantation of these cells into the lateral ventricles of neonatal mice and demonstrated that the regional identity specified in vitro was retained and not altered by transplantation into the brain environment. Excitingly, once transplanted, these cells also developed end-feet typical of those associated with astrocytes directly contacting blood vessels—suggesting that these cells also were able to participate in the formation of the blood-brain barrier.

Later studies generated astrocytes from human iPSC using different methodologies and demonstrated that, when compared with the studies of Krencic, astrocytes could be generated more quickly (90 days when compared to 180 days). The resulting astrocytes had many appropriate astrocytic properties beyond GFAP expression that included the secretion of the growth factors including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as well as glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). When co-cultured with motor neurons, these astrocytes also enhanced neuronal survival and neurite outgrowth. In an elegant addition to the study, the application of fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) resulted in the development of more mature “quiescent” protoplasmic astrocytes when compared with those of less mature fibrous astrocytes generated without the addition of this factor. These more mature astrocytic phenotypes showed a relative downregulation of GFAP and increases in glutamate transporter expression. (Roybon et al., 2013).

Haidet-Philips and colleagues (Haidet-Phillips et al., 2014) went on to demonstrate that iPSC-derived astrocyte progenitors grown in vitro, but not exposed to FGF1, were capable of further maturation with morphological features typically associated with astrocytes in vivo and upregulation of astrocyte-relevant genes (including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Aquaporin 4, and excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), among others), following transplantation into a rodent model. That work also demonstrated that astrocyte progenitors derived from iPSCs had similar gene signatures following differentiation when compared to ESC-derived astrocyte progenitors. These data would suggest that the astrocytes seen in culture as defined by GFAP+ immunostaining only are likely relatively immature and are capable of further differentiation in an in vivo environment over longer timeframes.

Oligodendrocytes

Human oligodendrocytes have also been generated (Ogawa et al., 2011). Using two different protocols, investigators successfully obtained oligodendrocytes identified by immunostaining of O4. This represented a significant advancement in iPSC glial differentiation and proof of principle; despite the low efficiency (0.01%) of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Two years later, Wang and colleagues built on that discovery to significantly improve the protocol's oligodendrocyte yield (Wang et al., 2013). The maturation of these cells over a 120 day period was required to have a stable and functional population. They also reported a strong differentiation efficacy into oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC), which allowed them to perform some in vivo studies. Interestingly, following transplantation into rodent brain, approximately half of the OPCs matured to become oligodendrocytes, while the other half became astrocytes. Finally, they were able to elegantly demonstrate their capacity for myelination through the use of a mouse model of hypomyelination (shiverer mouse). Following transplantation into corpus collosum of neonatal shiverer mice, human iPSC-derived OPCs were capable of myelinating the corpus collosum and prolonged survival in this mouse model.

Microglia

Microglia have been demonstrated to play a role in ALS disease progression as demonstrated using rodent microglia from varying sources in vitro. To date, however, we have not identified any reports of human iPSC-derived microglial differentiation.

Schwann Cells

In 2012, Liu and colleagues were the first to report successfully generating functional Schwann cells from iPSC. Not only did these cells exhibit markers associated with Schwann cell identity (GFAP, S100β and p75) but they also myelinated rodent dorsal root ganglia neurons in vitro. (Liu et al., 2012b). This protocol opens the door to understanding Schwann cell biology as well as the application of these protocols to the investigation of neuronal regeneration and axon guidance.

Muscle

Induced pluripotent stem cells have been differentiated into skeletal muscle cells. The properties of the cells generated from different groups vary (reviewed by (Salani et al., 2012))(Darabi et al., 2012). However, the current consensus is that the cells generated are myogenic progenitors, and may be too immature to yet display the full spectrum of characteristics necessary to model a late-onset disease such as ALS.

Human iPSC-derived neural cells for in vitro ALS modeling (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Human iPSC from ALS patients differentiate into neural cell subtypes.

Fibroblasts (or other tissues) from patients with familial ALS (FALS), sporadic ALS (SALS), and controls are genetically reprogrammed to form induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). Cells from varying ALS genotypes and phenotypes can subsequently be differentiated into motor neurons, astrocytes, or other non-neuronal (not shown) cells for further studies of disease. Gene correction methods exist to delete mutant genes from FALS patients to create control iPSC on the same genetic background of the ALS patient—thus allowing for patient-specific controls.

The generation of ALS-relevant cell lineages offers an enormous opportunity for investigating ALS pathobiology. Recent studies have suggested that some ALS-relevant phenotypes may be modeled in vitro. To date, most have utilized human iPSC-derived neural cells from known ALS gene mutations.

iPSC-derived Motor Neurons from ALS patients

SOD1

Mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) have been the most studied mutations related to ALS. Chen and colleagues leveraged this by creating iPSC-derived motor neurons from patients with the most common North American ALS genotype, SOD1A4V, as well as SOD1D90A. Since one concern when utilizing human tissues relates to the heterogeneity of human genetic background, these investigators used TALEN-based homologous recombination to correct the SOD1D90A mutation and thus allow for an assessment of the SOD1D90A mutation on an otherwise identical genetic background. By using Notch inhibitors, they were also able to increase the yield of Hb9+ motor neurons to 85% of the entire cellular population which lays the foundation for future studies on relatively pure motor neuron populations without the need for cell sorting. Pathologically, iPSC-derived motor neurons possessing SOD1 mutations also developed neurofilament (NF) inclusions as has been previously described in transgenic SOD1 mouse models (Bruijn et al., 1998; Hirano et al., 1984; Tu et al., 1996). This appeared to be related to neurofilament misregulation and also resulted in axonal pathology in the affected cells (Chen et al., 2014). Other iPSC-lines from patients carrying SOD1 mutations have been created including the SOD1L144F mutation (detailed as part of the discussion on iPSC-derived motor neuron differentiation)(Dimos et al., 2008) and more recently SOD1N87S and SOD1S106L (Chestkov et al., 2014)

TDP-43

Another class of genes has been linked to ALS consisting of proteins involved in RNA pathways including the tar DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43)(Kabashi et al., 2008; Sreedharan et al., 2008). To investigate the biology of mutations in this protein, Egawa and colleagues generated iPSC from three ALS patients carrying TDP-43 mutations (Q343R, M337V, and G298S). They found that much like pathological samples taken from ALS neural tissues, the iPSC-derived neurons developed cytosolic aggregates containing TDP-43. Phenotypically, isolated motor neurons identified using an Hb9∷GFP promoter/reporter construct demonstrated reduced neurite length accompanied by a reduction in the gene expression of intermediate neurofilaments. As cell stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been proposed as a potential mechanism in motor neuron pathology, the investigators challenged iPSC-derived motor neurons with arsenite. They found that iPSC-derived motor neurons harboring TDP-43 mutations were more sensitive to arsenite than controls and that this toxicity could be rescued with the histone acetyltransferase inhibitor anacardic acid (Egawa et al., 2012). This study, although not necessarily a platform for drug screening, did highlight that iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients had a unique pathology related to the presence of TDP-43 mutations, were more susceptible to cellular stress, and that this phenomenon could be rescued using a specific pharmacologic compound.

Bilican and Chandran demonstrated that human-iPSC-derived motor neurons derived from a patient with TDP-43M337V ALS mutation also developed increased levels of insoluble TDP-43 protein, although there were no differences in the subcellular distributions of TDP43 in the mutant and control iPSC-derived motor neurons, with the majority of TDP-43 localized to the nucleus. Using a method that could provide a true platform for understanding disease mechanisms as well as for drug screening, the investigators employed automated fluorescence microscopy which allowed them to track the fate of individual motor neurons transfected with a Hb9∷GFP promoter/reporter construct. This process could be carried out in 96 well plates by sampling hundreds of individual cells. By inferring cell death as the absence of GFP expression in these neurons, a cumulative hazard of cell death could be generated for comparison. Indeed, iPSC-derived motor neurons with the TDP-43M337V mutation had a hazard ration of 2.76 for cell death. This risk could also be enhanced using an inhibitor of MAPK signaling (Bilican et al., 2012).

C9ORF72

The C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion has garnered interest since its discovery as a gene responsible for ALS and/or Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)(DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). The clinical observation that some patients develop FTD as well as ALS highlights the complexity of neurodegenerative disease biology and reinforces the concept that pathology can exist in other cell types besides motor neurons in patients with the combination of ALS/FTD. Therefore, modeling C9ORF72 ALS/FTD, resulted in an opportunity to study both motor neuron and less specific neuronal pathology. Almeida and colleagues were the first to utilize human iPSC from two patients with C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion repeats to create a neuronal population expressing the telencephalic marker BF1 (FOXG1). iPSC-derived neurons carrying the C9ORF72 repeat expansion did not seem to have any differences with respect to controls in their capacity to generate neurons. This was a particularly important observation for the further examination of C9ORF72-specific pathologies that followed. Interestingly, the resulting neurons possessed some of the hallmarks observed in the original description of these repeat expansions including RNA foci and RAN translation products. When challenged with an inhibitor of autophagy (3-MA), caspase-3 activation was increased significantly in C9ORF72 neurons when compared with controls. However, the susceptibility to cellular stress was not universal as compounds that induced mitochondrial dysfunction (rotenone), ER stress (tunicamycin), and kinase inhibition (staurosporine) did not appear to induce abnormalities in these cells (Almeida et al., 2013).

The potential for iPSCs to recapitulate some of the pathological findings seen in ALS patients with the C9ORF72 repeat expansion was reported in two manuscripts published in succession. Donnelly and colleagues replicated that iPSC-derived neurons (and motor neurons) from patients with C9ORF72 expansion repeats harbored characteristic pathology seen in patient autopsies, including RNA foci. The group also correlated the pathological findings observed in iPSC-derived neurons with autopsies from C9ORF72 patients. This human in vitro/in vivo correlate will likely receive more attention moving forward, given that animal models of ALS have not always been faithful in reproducing human ALS pathophysiology—particularly as it relates to ALS therapeutics. Interestingly, these C9ORF72 iPSC-derived neurons were also more susceptible to glutamate excitotoxicity than control iPSC-derived neurons. The demonstration that they may be more susceptible to an ALS-relevant insult adds another layer of opportunity for understanding how neurons and motor neurons in ALS respond to cell stress—another developing theme in ALS pathobiology. Finally, this group also argued that in vitro iPSC modeling might provide a platform for screening potential therapeutics. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have been employed as a potential treatment for ALS (Smith et al., 2006) as well as a number of other disorders. The investigators screened several ASOs in vitro to demonstrate that C9ORF72 RNA foci presence could be reduced in iPSC-derived neurons following their incubation with a subset of ASOs (Donnelly et al., 2013).

In a careful and important analysis, investigators employed a non-integrating episomal plasmid vector system to avoid potential deleterious effects of random insertion of proviral sequences into the genome. They found that in two of the iPSC-derived motor neuron lines, a shift in the number of C9ORF72 expansion repeats appeared when fibroblasts from donor patients were reprogrammed to iPSCs. A further contraction of repeat length was also seen in one line following the differentiation into motor neurons. Phenotypically, these iPSC-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 expansions also had an increase in the number of RNA foci. Unlike the report by Donnelly and colleagues, the iPSC-derived neurons in this study did not show evidence for C9ORF72 RAN translation products. These cells did, however, show an increase in genes involved in regulating membrane excitability and when studied electrophysiologically, these cells showed reduced excitability upon depolarization—consistent with the observed increases in the expression potassium voltage-gated (KCNQ3) channel. Mirroring the study by Donnelly, the use of antisense oligonucleotides to knockdown C9ORF72 expansion also reduced the number of RNA foci seen in neuronal populations (Sareen et al., 2013).

VAPB

Mutations in the vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein-B/C (VAPB/C) gene have been identified as an autosomal dominant form of ALS (ALS8)(Nishimura et al., 2004a; Nishimura et al., 2004b). This is a membrane-associated protein but it is not clear whether the mutation leads to a gain of function defect or a dominant negative effect with loss of VAPB as the key to pathogenesis. iPSC were derived from a patient with the VAPBP56S mutation. The presence of the mutation did not seem to affect motor neuron differentiation or survival. The potential utility of using iPSC from patients, as opposed to overexpression of mutant proteins in cellular models, was highlighted by the observation that although cytoplasmic aggregates of VAPB have been seen in VAPB overexpression models, no such aggregates were noted. The fact that only a single patient line was studied limits broad interpretation. The investigators did, however, observe that in iPSC-derived motor neurons with the VAPBP56S mutation, there was no upregulation of the VAPB protein following neuronal differentiation (Mitne-Neto et al., 2011).

Sporadic ALS

In a study where a large group (16 patients) of sporadic ALS iPSC were made, three of those patients had iPSC-derived motor neurons in which aggregated TDP-43 was identified within the nucleus. These aggregations seemed to be specific for motor neurons, as fibroblasts obtained from these same patients did not harbor these aggregates. Interestingly, an autopsy from one of these patients found TDP-43 aggregates in both alpha motor neurons as well as cortical neurons. Although not definitive of the relationship for all of the iPSC-derived motor neurons, this evidence does support the idea that iPSC-derived motor neurons cultured in vitro may mirror pathology observed in patient neural tissues. This study is also of interest in that both lower motor neurons as well as corticospinal motor neurons (as defined by antibody staining to CTIP2) were generated (Burkhardt et al., 2013).

iPSC-derived Astrocytes from ALS patients

Abnormalities in astrocyte function have been demonstrated to play a role in ALS pathobiology utilizing human and rodent ALS astrocytes models in vitro as well as in vivo. These findings correlate with what has been demonstrated neuropathologically in ALS patients with regard to abnormalities in astrocyte biology. Interestingly, NPC-derived astrocytes from autopsied human ALS spinal cord have demonstrated toxicity to motor neurons (Haidet-Phillips et al., 2011). This toxicity has also been demonstrated after the isolation of astrocyte precursors from autopsied sporadic human ALS although the mechanisms behind that toxicity were not found to be the same (Re et al., 2014).

In 2013, Serio and colleagues reported the unexpected observation that human iPSC-derived astrocytes with TDP-43 mutations were not toxic to wildtype motor neurons in vitro. Interestingly, however, they did observe an increase in the cumulative risk of astrocyte death associated with the specific TDP-43M337V mutation (Serio et al., 2013). The suggestion that astrocytes, usually thought to be resistant to ALS-related pathology, could be affected by the presence of mutant TDP-43 is of interest. Whether these observations are specific to mutations in TDP-43, and not other hereditary forms of ALS, remains to be explored.

Challenges

Considering the report of human iPSC development occurred in 2007, the challenges in modeling ALS using these in vitro technologies are numerous.

Methods

Reproducibility amongst laboratories has always been a challenge in science and medicine. Given the recent expansion of iPSC technologies, this is magnified as somatic cells have been reprogrammed using a variety of different strategies. These all result in iPSC which may harbor similar ALS mutations but may or may not have equal capacity for recapitulating disease phenotypes

The acquisition of mutations that may be acquired during reprogramming or subsequent passaging of iPSC has been identified as a potential complicating factor to this technology. In a very thorough study performed by several different laboratories, using integrating and non-integrating methods of reprogramming, investigators found that mutations were often present in fibroblasts prior to reprogramming. Still, other mutations occurred during or after reprogramming (Gore et al., 2011). The consequence of many of these mutations is not known but does provide pause when analyzing potential phenotypes thought to be related to disease. Karyotype analysis following reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSC is, in most laboratories, considered a standard for ensuring that findings that could be considered related to an ALS phenotype are not merely the result of chromosomal abnormalities. While a normal karyotype from source fibroblasts appears to be important in ensuring that significant karyotype abnormalities do not occur during reprogramming, aneuploidy has been described even following the reprogramming of normal fibroblasts (reviewed by Martins-Taylor (Martins-Taylor and Xu, 2012)).

How well does a single clone from an ALS patient model disease in that individual or more broadly, many patients with ALS? Analyzing more than one clone from an individual may help to lend confidence that the findings observed are reflective of the individual ALS patient rather than a single clone obtained from that individual.

Finally, the multiplicity of differentiation protocols makes comparing cells and results from lab to lab both important and challenging. The standards to define a cellular phenotype as, for example, a “motor neuron” or an “astrocyte” generated from iPSC differentiation in vitro, has often rested on the identification of a small subset of immunohistochemical markers of motor neuron (Hb9) or astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein-GFAP). In addition, the purity of the population studied is always of concern since the non-cell autonomous effects of other neural cell types can influence interpretation of experimental results. As our understanding of neuronal and astrocytic subtype identity becomes more mature, additional markers (as well as functional studies) will likely become integrated into the field to achieve more precise technical standards.

Challenges of scale

Most of the studies reviewed here have utilized a handful of cell lines, often from a single ALS gene mutation and/or patient, carried out as proof-of-concept that some features of ALS pathobiology can be modeled with human cells in vitro. It is tempting, however, to envision that iPSC could be developed from every ALS patient towards “individualized medicine” where mechanisms of disease and patient-specific therapy could be tested for each individual in vitro. One could envision that an ALS “clinical trial in a dish” could be a goal of the field. However, in a field where there is no single or group of cell-death mechanisms yet discovered that can account for the heterogeneity of both sporadic and familial ALS, it may be that large sample sizes are required to provide fidelity with regard to common (or unique) disease mechanisms that can ensure a targeted approach to patient therapy.

Cost

Current costs for cell reprogramming of a patient-derived fibroblast into an IPSC are several thousand dollars. Such costs would not include additional supplies necessary for maintenance and subsequent differentiation from iPSC into motor neurons (at least 30 days). Astrocyte differentiation has required even longer times for differentiation into cells which possess some markers of astrocyte identity (at least 60 days). Other expenses including karyotyping, the development of several clones from a single patient, and storage of these numerous iPSC lines all currently serve to make investigation expensive both monetarily as well as temporally. One would expect, however, that as technologies improve, costs would be reduced as well. Technological advances, for example, have included direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts into functional neurons without creating iPSC lines (Pang et al., 2011), which could eventually reduce both time and costs.

Recapitulating aging in vitro

How effectively cultured neural cells (whether iPSC-derived, ESC-derived, or cultured from fetal neural tissue) recapitulate disease mechanisms occurring in whole organisms where complex networks are formed amongst numerous cell types, remains a question that requires attention. For example, although iPSC are generated from tissues (skin fibroblasts, peripheral blood monocytes) harvested from adults, it should not necessarily be assumed that the resulting iPSC in culture will recapitulate an adult-onset neurodegenerative disease. Given that some cell types generated from iPSC do not appear to reach fully mature phenotypes, concerns arise that iPSC generation erases age-associated characteristics making it challenging to study adult late-onset neurodegeneration. Liu, Ding and Belmonte reviewed the challenges posed to aging the cells generated to potentiate the tools that iPSC represent. They concluded that most cells generated through the current methodologies represent early childhood phenotypes and may require triggers including “pro-aging medium”, inducers of oxidative stress, DNA damaging agents, or proteasome inhibitors to model adulthood without waiting months or years (Liu et al., 2012a). Miller and colleagues have proposed an innovative approach with neurons generated from iPSC, more specifically in Parkinson's Disease (PD) research. They have been using progerin, the truncated nuclear lamin responsible for the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, to accelerate the aging process. They were able to not only demonstrate that the aging process does takes place in neurons, but also that hallmarks of Parkinson's Disease can be found in neurons generated from these patients. This exciting breakthrough opens new opportunities for all late onset neurodegenerative diseases (Miller et al., 2013).

Modeling sporadic vs. hereditary ALS forms

For the last 20 years, the study of mechanisms of ALS, as well as the design for potential ALS therapeutics, has relied heavily on transgenic overexpression of human mutant SOD1 in mice to create a phenotype with slowly progressing limb weakness, death after four months, and pathological findings including motor neuron loss (Gurney et al., 1994). Other ALS models have also relied on familial forms of ALS—most notably models of human TDP-43, FUS, and VCP (reviewed by McGoldrick (McGoldrick et al., 2013)). While a significant amount of information can be learned from these, it remains that nearly 90% of all ALS occurs without a family history of ALS. However, whether iPSC-derived neural cell subtypes from sporadic ALS have similar properties to those that have been described for familial forms of ALS has yet to be determined and remains the major challenge to the field in developing therapeutics that may be suitable for the majority of ALS patients.

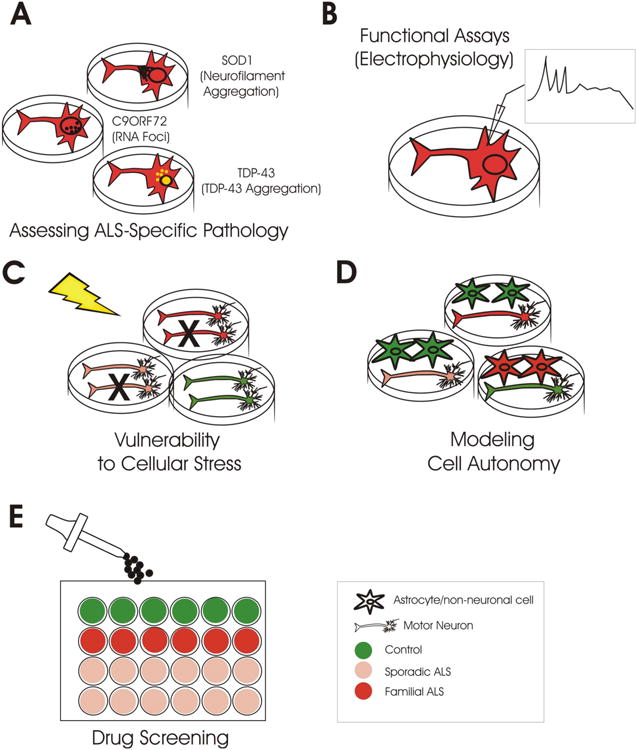

Opportunities (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Opportunities for using iPSC from ALS patients.

Once developed iPSC-derived neural cell subtypes can be of value for a number of lines of investigation. A. The examination of subcellular aggregates and other pathologies described in human autopsy tissues can be assessed in both familial ALS as well as sporadic ALS iPSC. B. Assays to assess physiological characteristics as well as biochemical profiles of iPSC-derived neural cells may bridge genotype/phenotype correlations. C. The capacity of ALS iPSC-derived neural cells to respond to a number of cellular stress paradigms may provide insight into environmental cascades relevant to disease. D. The capability of generating multiple neural cell types allows for understanding of interplay between normal and disease cell subtypes. E. iPSC-derived neural cell culture may be amenable to high throughput screening to allow for the study of potential neuroprotective compounds.

Humanizing ALS modeling

While intrinsically, it may be logical to assume that using human cells will recapitulate ALS disease mechanisms more faithfully and thus be better for understanding disease as well as designing therapeutics, there are no data to date that would suggest this is the case for ALS. This is at least partly related to the fact that the generation of human iPSC-derived neural cells has only recently been developed and no potential ALS therapies or mechanisms of disease identified in iPSC in vitro models have had time to be fully tested in a clinical setting.

Despite the unknown, the field now has the opportunity to take full advantage of the ability to generate cells from ALS patients with well characterized disease phenotypes—utilizing clinical histories, imaging data, electrophysiological studies, genetic histories, and pathology to begin modeling ALS more specifically. This ability is particularly powerful because, up until the reprogramming of adult somatic cells, there were severe limitations using ESC to model an adult neurodegenerative disease.

Modeling cell autonomy in ALS

In the current review it has been noted that several groups have developed in vitro and in vivo models for assessing non-neuronal contributions to disease pathogenesis using rodent ALS models extensively (Ilieva et al., 2009) as well as some reports of autopsy derived human NSC-derived astrocytes (Haidet-Phillips et al., 2011) or autopsy derived human astrocytes for modeling the toxicity of both sporadic and familial ALS on wildtype motor neurons (Re et al., 2014). Whether iPSC-derived neural cells possess the same toxicity to motor neurons as those derived from neural tissues remains to be fully elucidated. The use of human iPSC-derived neural cells affords an opportunity to investigate these same contributions with an almost endless combination of different neural cell subtypes carrying different ALS mutations and/or phenotypes.

Drug screening

If a disease-relevant phenotype can be established from ALS iPSC-derived motor neurons that can be readily measured, this opens the door to the development of small-molecule screens. In a first step towards this goal, Yang and colleagues utilized ESC-derived motor neurons from both wildtype and mutant SOD1 mice to carry out such a screen. Using the Hb9∷GFP promoter/reporter to identify motor neurons, they used a 384 well high throughput screening format to identify factors which could promote survival. They identified kenpaullone (a GSK-3 inhibitor) as a small molecule that could improve motor neuron survival in both wildtype and mutant SOD1 motor neurons. They extended these observations showing that kenpaullone was also protective to control human iPSC-derived motor neurons. The demonstration that screening small molecules that could protect both rodent and human motor neurons from cell death is a first step towards the ability to examine specific responses of individual patients with ALS to tested compounds (Yang et al., 2013).

Table 1.

| iPSC-derived cell subtype | ALS gene mutation | ALS Phenotype | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Neurons | SOD1L144F | Not studied | Dimos | 2008 |

| Motor Neurons | SOD1A4V SOD1N139K SOD1V148G |

Not studied | Amoroso | 2013 |

| Motor Neurons | SOD1N87S SOD1S106L |

Not studied | Chestkov | 2014 |

| Motor Neurons | SOD1A4V SOD1D90A |

Neurofilament misregulation and aggregation Neurite degeneration |

Chen | 2014 |

| Motor Neurons | TDP-43Q343R TDP-43M337V TDP-43G298S |

TDP-43 cytosolic aggregates Reduced neurite length Increased susceptibility to arsenite exposure |

Egawa | 2012 |

| Motor Neurons | TDP-43M337V | Increases in insoluble TDP-43 Increase cumulative risk of death Increased susceptibility to inhibition of MAPK signaling |

Bilican | 2012 |

| Motor Neurons | Sporadic | TDP-43 intranuclear aggregates noted in subset of sporadic ALS iPSC-derived motor neurons | Burkhardt | 2013 |

| Neurons | C9ORF72 | RNA foci RAN translation products Increased susceptibility to cellular stress from inhibition of autophagy |

Almeida | 2013 |

| Motor Neuron/Neuron | C9ORF72 | RNA foci RAN translation products Increased susceptibility to glutamate excitotoxicity |

Donnelly | 2013 |

| Motor Neurons/Neurons | C9ORF72 | RNA foci Reduced electrical excitability |

Sareen | 2013 |

| Motor Neurons | VAPBP56S | Reduced levels of VAPB No cytosolic aggregates |

Mitne-Neto | 2011 |

| Astrocytes | TDP43M337V | Increase cumulative risk of death | Serio | 2013 |

Highlights.

Induced pluripotent cells have a distinct advantage over embryonic stem cells in modeling ALS.

IPSC have the capability of being derived from both familial as well as sporadic forms of ALS.

iPSC can be differentiated into a variety of different ALS-relevant cell subtypes

Despite the potential of iPSC, a number of methodological and monetary constraints still exist.

iPSC have applications in understanding disease mechanisms and screening therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

N.J. Maragakis receives funding from NIH/NINDS: 5U01NS062713 and Department of Defense ALSRP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almeida S, Gascon E, Tran H, Chou HJ, Gendron TF, Degroot S, Tapper AR, Sellier C, Charlet-Berguerand N, Karydas A, et al. Modeling key pathological features of frontotemporal dementia with C90RF72 repeat expansion in iPSC-derived human neurons. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;126:385–399. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1149-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoroso MW, Croft GF, Williams DJ, O'Keeffe S, Carrasco MA, Davis AR, Roybon L, Oakley DH, Maniatis T, Henderson CE, et al. Accelerated high-yield generation of limb-innervating motor neurons from human stem cells. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:574–586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0906-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatar M. Lost in translation: treatment trials in the SOD1 mouse and in human ALS. NeurobiolDis. 2007;26:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilican B, Serio A, Barmada SJ, Nishimura AL, Sullivan GJ, Carrasco M, Phatnani HP, Puddifoot CA, Story D, Fletcher J, et al. Mutant induced pluripotent stem cell lines recapitulate aspects of TDP-43 proteinopathies and reveal cell-specific vulnerability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:5803–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn LI, Houseweart MK, Kato S, Anderson KL, Anderson SD, Ohama E, Reaume AG, Scott RW, Cleveland DW. Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1. Science. 1998;281:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt MF, Martinez FJ, Wright S, Ramos C, Volfson D, Mason M, Garnes J, Dang V, Lievers J, Shoukat-Mumtaz U, et al. A cellular model for sporadic ALS using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2013;56:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Qian K, Du Z, Cao J, Petersen A, Liu H, Blackbourn LWt, Huang CL, Errigo A, Yin Y, et al. Modeling ALS with iPSCs Reveals that Mutant SOD1 Misregulates Neurofilament Balance in Motor Neurons. Cell stem cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chestkov IV, Vasilieva EA, Illarioshkin SN, Lagarkova MA, Kiselev SL. Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for SOD1-Associated Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathogenesis Studies. Acta naturae. 2014;6:54–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi R, Arpke RW, Irion S, Dimos JT, Grskovic M, Kyba M, Perlingeiro RC. Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell stem cell. 2012;10:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C90RF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio FP, Boulting GL, Bobrowicz S, Eggan KC. Human embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons are sensitive to the toxic effect of glial cells carrying an ALS-causing mutation. Cell stem cell. 2008;3:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, Goland R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly CJ, Zhang PW, Pham JT, Heusler AR, Mistry NA, Vidensky S, Daley EL, Poth EM, Hoover B, Fines DM, et al. RNA toxicity from the ALS/FTD C90RF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron. 2013;80:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa N, Kitaoka S, Tsukita K, Naitoh M, Takahashi K, Yamamoto T, Adachi F, Kondo T, Okita K, Asaka I, et al. Drug screening for ALS using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:145ra104. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A, Li Z, Fung HL, Young JE, Agarwal S, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Canto I, Giorgetti A, Israel MA, Kiskinis E, et al. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet-Phillips AM, Hester ME, Miranda CJ, Meyer K, Braun L, Frakes A, Song S, Likhite S, Murtha MJ, Foust KD, et al. Astrocytes from familial and sporadic ALS patients are toxic to motor neurons. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet-Phillips AM, Roybon L, Gross SK, Tuteja A, Donnelly CJ, Richard JP, Ko M, Sherman A, Eggan K, Henderson CE, et al. Gene profiling of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived astrocyte progenitors following spinal cord engraftment. Stem cells translational medicine. 2014;3:575–585. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano A, Nakano I, Kurland LT, Mulder DW, Holley PW, Saccomano G. Fine structural study of neurofibrillary changes in a family with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JNeuropatholExpNeurol. 1984;43:471–480. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilieva H, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. JCell Biol. 2009;187:761–772. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature genetics. 2008;40:572–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XJ, Du ZW, Zarnowska ED, Pankratz M, Hansen LO, Pearce RA, Zhang SC. Specification of motoneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GH, Ding Z, Izpisua Belmonte JC. iPSC technology to study human aging and aging-related disorders. Current opinion in cell biology. 2012a;24:765–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Spusta SC, Mi R, Lassiter RN, Stark MR, Hoke A, Rao MS, Zeng X. Human neural crest stem cells derived from human ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells: induction, maintenance, and differentiation into functional Schwann cells. Stem cells translational medicine. 2012b;1:266–278. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MC, Muotri AR, Mu Y, Smith AM, Cezar GG, Gage FH. Non-cell-autonomous effect of human SOD1 G37R astrocytes on motor neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2008;3:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Taylor K, Xu RH. Concise review: Genomic stability of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:22–27. doi: 10.1002/stem.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick P, Joyce PI, Fisher EM, Greensmith L. Rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1421–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Ganat YM, Kishinevsky S, Bowman RL, Liu B, Tu EY, Mandal PK, Vera E, Shim JW, Kriks S, et al. Human iPSC-based modeling of late-onset disease via progerin-induced aging. Cell stem cell. 2013;13:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitne-Neto M, Machado-Costa M, Marchetto MC, Bengtson MH, Joazeiro CA, Tsuda H, Bellen HJ, Silva HC, Oliveira AS, Lazar M, et al. Downregulation of VAPB expression in motor neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of ALS8 patients. Human molecular genetics. 2011;20:3642–3652. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura AL, Mitne-Neto M, Silva HC, Oliveira JR, Vainzof M, Zatz M. A novel locus for late onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease variant at 20q13. Journal of medical genetics. 2004a;41:315–320. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura AL, Mitne-Neto M, Silva HC, Richieri-Costa A, Middleton S, Cascio D, Kok F, Oliveira JR, Gillingwater T, Webb J, et al. A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. American journal of human genetics. 2004b;75:822–831. doi: 10.1086/425287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Tokumoto Y, Miyake J, Nagamune T. Induction of oligodendrocyte differentiation from adult human fibroblast-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. In vitro cellular & developmental biology Animal. 2011;47:464–469. doi: 10.1007/s11626-011-9435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, Yang TQ, Citri A, Sebastiano V, Marro S, Sudhof TC, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadeas ST, Kraig SE, O'Banion C, Lepore AC, Maragakis NJ. Astrocytes carrying the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1G93A) mutation induce wild-type motor neuron degeneration in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:17803–17808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103141108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re DB, Le Verche V, Yu C, Amoroso MW, Politi KA, Phani S, Ikiz B, Hoffmann L, Koolen M, Nagata T, et al. Necroptosis drives motor neuron death in models of both sporadic and familial ALS. Neuron. 2014;81:1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C90RF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron. 2011;72:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roybon L, Lamas NJ, Garcia-Diaz A, Yang EJ, Sattler R, Jackson-Lewis V, Kim YA, Kachel CA, Rothstein JD, Przedborski S, et al. Human stem cell-derived spinal cord astrocytes with defined mature or reactive phenotypes. Cell reports. 2013;4:1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salani S, Donadoni C, Rizzo F, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Corti S. Generation of skeletal muscle cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells as an in vitro model and for therapy of muscular dystrophies. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2012;16:1353–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen D, O'Rourke JG, Meera P, Muhammad AK, Grant S, Simpkinson M, Bell S, Carmona S, Ornelas L, Sahabian A, et al. Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C90RF72 repeat expansion. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:208ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serio A, Bilican B, Barmada SJ, Ando DM, Zhao C, Siller R, Burr K, Haghi G, Story D, Nishimura AL, et al. Astrocyte pathology and the absence of non-cell autonomy in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300398110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Miller TM, Yamanaka K, Monia BP, Condon TP, Hung G, Lobsiger CS, Ward CM, McAlonis-Downes M, Wei H, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2290–2296. doi: 10.1172/JCI25424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu PH, Raju P, Robinson KA, Gurney ME, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Transgenic mice carrying a human mutant superoxide dismutase transgene develop neuronal cytoskeletal pathology resembling human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis lesions. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1996;93:3155–3160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrat-Durebex C, Corcia P, Dangoumau A, Laumonnier F, Piver E, Gordon PH, Andres CR, Vourc'h P, Blasco H. Advances in cellular models to explore the pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Molecular neurobiology. 2014;49:966–983. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Bates J, Li X, Schanz S, Chandler-Militello D, Levine C, Maherali N, Studer L, Hochedlinger K, Windrem M, et al. Human iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can myelinate and rescue a mouse model of congenital hypomyelination. Cell stem cell. 2013;12:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Gupta SK, Kim KJ, Powers BE, Cerqueira A, Wainger BJ, Ngo HD, Rosowski KA, Schein PA, Ackeifi CA, et al. A small molecule screen in stem-cell-derived motor neurons identifies a kinase inhibitor as a candidate therapeutic for ALS. Cell stem cell. 2013;12:713–726. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]