Abstract

Hierarchical surface roughness of titanium and titanium alloy implants plays an important role in osseointegration. In vitro and in vivo studies show greater osteoblast differentiation and bone formation when implants have submicron-scale textured surfaces. In this study, we tested the potential benefit of combining a submicron-scale textured surface with three-dimensional (3D) structure on osteoblast differentiation and the involvement of an integrin-driven mechanism. 3D titanium scaffolds were made using orderly oriented titanium meshes and microroughness was added to the wire surface by acid-etching. MG63 and human osteoblasts were seeded on 3D scaffolds and 2D surfaces with or without acid etching. At confluence, increased osteocalcin, vascular endothelial growth factor, osteoprotegerin (OPG), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity were observed in MG63 and human osteoblasts on 3D scaffolds in comparison to 2D surfaces at the protein level, indicating enhanced osteoblast differentiation. To further investigate the mechanism of osteoblast-3D scaffold interaction, the role of integrin α2β1 was examined. The results showed β1 and α2β1 integrin silencing abolished the increase in osteoblastic differentiation markers on 3D scaffolds. Time course studies showed osteoblasts matured faster in the 3D environment in the early stage of culture, while as cells proliferated, the maturation slowed down to a comparative level as 2D surfaces. After 12 days of postconfluent culture, osteoblasts on 3D scaffolds showed a second-phase increase in ALP activity. This study shows that osteoblastic differentiation is improved on 3D scaffolds with submicron-scale texture and is mediated by integrin α2β1.

Keywords: titanium surface properties, 3D, mesh, osteoblast differentiation

INTRODUCTION

Titanium and its alloys are commonly used materials for implants in dental and orthopedic applications because of their mechanical properties (e.g., weight-to-strength ratio) and good biocompatibility particularly in bone.1,2 Osseointegration, the direct structural and functional connection between ordered, living bone and the surface of a load-carrying implant,3 is crucial to implant success.4,5 Many studies focus on developing new surface features to achieve better osseointegration.6–8 In vitro studies show that osteoblast differentiation is increased on Ti surfaces with micro-scale roughness,9–11 and in vivo studies confirm that osteogenesis is enhanced compared to implants with smooth surfaces.12,13 In addition to microstructured surfaces, titanium surfaces with nanostructure modifications also increase osteocalcin (OCN), a marker of a well differentiated osteoblast, and upregulate gene expression of the bone-related proteins in osteoblast cultures.14,15

Compared to two-dimensional (2D) surface modifications, 3D porous scaffolds could allow bone to grow into the component, providing improved fixation and producing a system that enables stresses to be transferred from the implant to the bone.16–20 Porous materials have been used for bone tissue engineering. Ceramics with similar mineral to that of bone, such as hydroxyapatite and beta-tricalcium phosphate, are biocompatible and have been used clinically with bone marrow-derived osteoprogenitor cells to treat bone defects.21,22 However, poor mechanical properties limit the applications of porous ceramic materials for load-bearing implants.

These studies have shown that successful bone scaffold design of nonresorbable implants requires macroporosity to permit vascular ingrowth,23,24 and an osteoconductive surface to facilitate migration of osteoprogenitor cells, as wells as an ostogenic surface to facilitate osteoblast differentiation.25–28 A number of approaches have been used to achieve these design parameters. Galante and Rostoker29 pioneered the development of fiber-metal leading to its clinical use as a porous coating in hip and knee arthroplasty. In the last 20 years, a variety of porous coatings and materials, such as sintered Ti powders, diffusion-bonded Ti, fiber metal, and plasma-sprayed Ti8,30,31 have also been used to obtain biological fixation of porous implants and bone. While these methods provide the 3D properties needed for mechanical fixation, they have not considered surface microtopography as a critical variable.

Osteoblasts interact with their substrate via integrin binding to the extracellular matrix proteins adsorbed to the surface. Cellular feedback mechanisms cause integrin expression to be substrate sensitive.32–34 For instance, osteoblasts express primarily α2β1 when grown on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS), but instead express α2β1 when grown on Ti and Ti6Al4V alloy.35 A previous study by our group showed that the β1 subunit and the α2β1 heterodimer play critical roles in osteoblast-response to microscale surface structure and surface energy of Ti substrate.36,37 Whether β1 and α2β1 integrin also contribute to osteoblast maturation on 3D Ti scaffolds is not known.

Studies using 2D cultures show that osteoblast differentiation is sensitive to surface features of the substrate, raising the question of whether cells are also sensitive to the 3D structure and the micron scale features within the 3D environment and what is the role of integrin α2β1 in this process. To address this question, we took advantage of a well-established model of osteoblast differentiation on biomaterial test substrates. MG63 human osteoblast-like cells and normal human osteoblasts were cultured on 3D scaffolds fabricated using Ti meshes and cell behavior on smooth and microstructured surfaces compared to smooth and microstructured Ti discs. Cells that were silenced for the integrin β1 subunit as well as cells silenced for both α2 and β1 subunits were used to assess their roles in osteoblastic differentiation within a 3D environment. Long-term osteoblastic differentiation within a 3D environment was also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication and characterization of 3D Ti scaffolds

Orderly oriented titanium meshes (Xinxing Ti Co., Anping, Hebei, China) were cut by laser to form circular meshes with a diameter of 15 mm and a thickness of 200 µm. A hydraulic press applying a pressure of 5 tons was used to compress four layers of meshes together to form a circular scaffold. The final titanium scaffold had a diameter of 15 mm and a thickness of 500–550 µm. Pretreated (PT) titanium discs were provided by Institut Straumann AG, Basel, Switzerland and were used as the 2D surface control. The 15 mm diameter discs were provided with a surface texture (Ra = 400 nm), were defined as smooth in comparison to the various test surfaces. These disks have been well characterized in previous studies.38

To create the rough texture on 2D surfaces and 3D scaffolds, the disks and scaffolds were etched with a mixture of 98% sulfuric acid and 60% nitric acid (1:1, v/v). PT discs and 3D scaffolds were placed in the acid mixture and reacted in a boiling water bath for 45 min. After acid etching, samples were cleaned and sterilized as described previously.39 Briefly, samples were cleaned by sonication in 2% micro-90 detergent (International Products Corporation, Burlington, NJ) in distilled ultrapure water twice for 15 min followed by sequential ultrasonic baths twice for 15 min in reagent grade acetone, isopropanol, and ethanol. After cleaning, samples were sonicated three times for 10 min with ultrapure water and then steam autoclaved.

The surface structures on the 3D scaffolds were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Ultra 60 FEG-SEM, Carl Zeiss SMT, Cambridge, UK) using 5 kV accelerating voltage and 30 µm aperture.

The chemical composition of the surface of the discs and scaffolds was examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Thermo K-Alpha XPS, thermo Fisher Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL). The instrument was equipped with a mono chromatic Al Kα X-ray source (hv = 1468.6 eV) and spectra were collected using an X-ray spot size of 100 µm and a pass energy of 200 eV, with 1 eV increments, at 55° takeoff angle. Three randomly selected samples of each group were analyzed by examining five different spots per sample. This analysis was repeated a second time to ensure validity of the results.

3D structure and surface roughness of the scaffolds were evaluated using laser confocal microscopy (LCM; Lext LCM, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). LCM analysis was performed over a 100 µm × 100 µm area using a scan height step of 30 nm and a cutoff wavelength of 100 µm. Three scans of each sample and at least two different samples per group were analyzed.

Cell culture

Human osteosarcoma-derived osteoblast-like MG63 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). This cell line is a well-characterized cell culture model and is used as a model for examining osteoblast differentiation on various biomaterials.40,41 Normal human osteoblasts were obtained from Lonza Group. The construction and selection of transfected integrin β1 silenced (shITG β1) and integrin α2β1 cosilenced (shITGα2β1) MG63 cells were described in previous studies.36,37 Silenced cell lines were thawed and cultured until confluence in T-75 flask before plating on titanium discs and scaffolds.

Wild type, shITGβ1 and shITGα2β1 MG63 cells, as well as normal human osteoblast cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere and 100% humidity. Sterilized titanium discs and scaffolds were put into untreated 24-well tissue culture plate. Cells (20,000 cells/well) were seeded on to TCPS, pretreated 2D discs (PT), acid etched PT, 3D scaffolds (3D) and acid etched 3D scaffolds. Media were changed 24 h after plating and every 48 h until cells on TCPS reached confluence. At confluence on TCPS, cells were fed with fresh media for 24 h and harvested from all surfaces. Conditioned media were collected for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Cell layers were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), followed by three sequential incubations for 10 min in 500 µL of 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Gibco, Life Technologies) at 37°C to release cells from the surfaces and scaffolds. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 2000 rpm (rotor diameter 12.8 cm) for 15 min, resuspended in 10 ml of saline solution and counted with a Z1 Coulter particle counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). After counting, cell suspensions were centrifuged again at 2000 rpm for 15 min; the cell pellets were resuspended in 500 µL of 0.05% Triton-X-100 in ddH2O and lysed by sonication.

To examine the proliferation and differentiation over longer periods of time, MG63 cells were cultured on TCPS, PT, and 3D scaffolds. When cells reached confluence on TCPS, the day was labeled as day 0. Cells on all surfaces were fed with fresh media and then every 48 h for 12 more days. Cells were sequentially harvested using the protocols disclosed above on days 2, 6, 8, 10, and 12.

Biochemical assays

Cell morphology was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Carl Zeiss SMT) using a 5-kV accelerating voltage and 30 µm aperture. MG63 cell differentiation was evaluated by examining the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of cell lysates and normalized by total protein content (Micro BCA Protein Assay kit; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The conditioned media were collected for the ELISA of the late osteoblastic differentiation marker osteocalcin (OCN) (Human Osteocalcin RIA kit, Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA), osteoprotegerin (OPG), a regulator of osteoclast production and activity, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a growth factor involved in vasculogenesis (DY805, Osteoprotegerin, DY293B VEGF Duoset, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical analysis

Data from characterization of the Ti scaffolds were presented as the mean ± one standard deviation (SD) for chemical composition and surface roughness performed on four different groups of samples. Data from cell experiments were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for six cultures per variable. All experiments were independently repeated at least twice to ensure validity of the observations and the representative results from an individual experiment are shown. Data were evaluated by analysis of variance, and significant differences between groups were determined using Bonferroni’s modification of Student’s t-test. A p value below 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Scaffold characterization

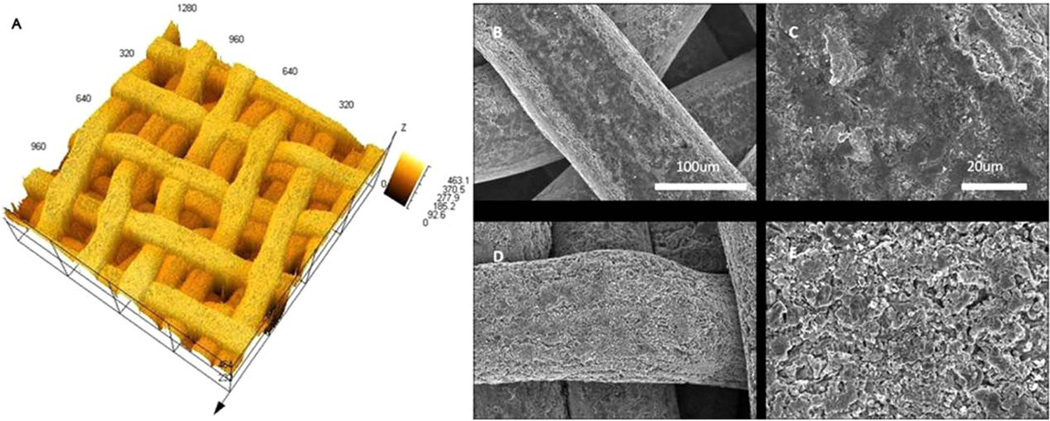

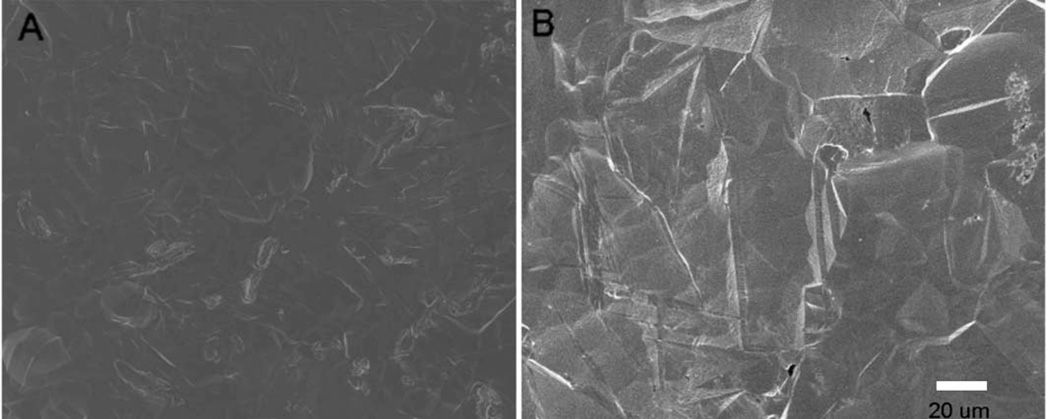

Laser confocal microscope images showed that 3D scaffolds had an average wire diameter of 150 µm and the pore size was also around 150 µm [Fig. 1(A)]. Scaffolds had an interconnected porous structure. SEM images showed the surface morphology of the titanium wire of 3D scaffolds before and after acid etching [Fig. 1(B–E)]. The surface of the PT disks before and after acid etching is shown in Figure 2(A,B). Prior to acid etching, the wire and the disc surfaces appeared relatively smooth, whereas after acid etching, the surface roughness increased. Quantitative measurements of the surfaces by laser confocal microscopy showed that after 45 min acid etching, the surface roughness of both 2D and 3D groups increased by an average of 200 nm (Table I).

FIGURE 1.

LCM and SEM images of 3D titanium scaffolds. A: The LCM image of 3D scaffold, which has interconnected porous structure, unit of the scale is µm. B–E: The surface structure of unetched (B and C) and acid etched (D and E) titanium wire. Increased surface roughness on were observed on acid-etched surfaces. The scale bar in (D) and (E) is the same as (B) and (C), respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

FIGURE 2.

SEM images of PT titanium discs before (A) and after (B) acid etching, Increased surface roughness was observed on the acid-etched surfaces.

TABLE I.

Elemental Composition and Surface Roughness ± Standard Deviation (SD)

| Elemental Composition (%) |

Surface Roughness, Sa (µm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Ti | O | C | Ca | |

| PT | 18.7 ±6.3 | 49.6 ±8.7 | 31.5 ±4.2 | - | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| Acid PT | 16.3±6.1 | 41.9 ±7.7 | 42.9 ±5.8 | - | 0.63 ±0.02 |

| 3D | 19.8 ±6.6 | 52.1 ±9.0 | 19.6 ±7.8 | 3.0 ±2.2 | 0.60 ±0.02 |

| Acid 3D | 18.4±5.8 | 45.7 ±9.9 | 35.2 ±6.4 | - | 0.83 ± 0.03 |

Chemical analysis by XPS showed O and Ti as the main chemical species in all groups (Table I). Similar chemical compositions were seen on the four different surfaces, which contained less than 20% titanium and 40–50% oxygen. Trace content of Ca was detected in the 3D group, but after acid treatment, no Ca was observed. An increased amount of carbon contamination was also observed on both 2D and 3D acid etched surfaces; the percentage of carbon was more than 10% higher than on nonetched specimens.

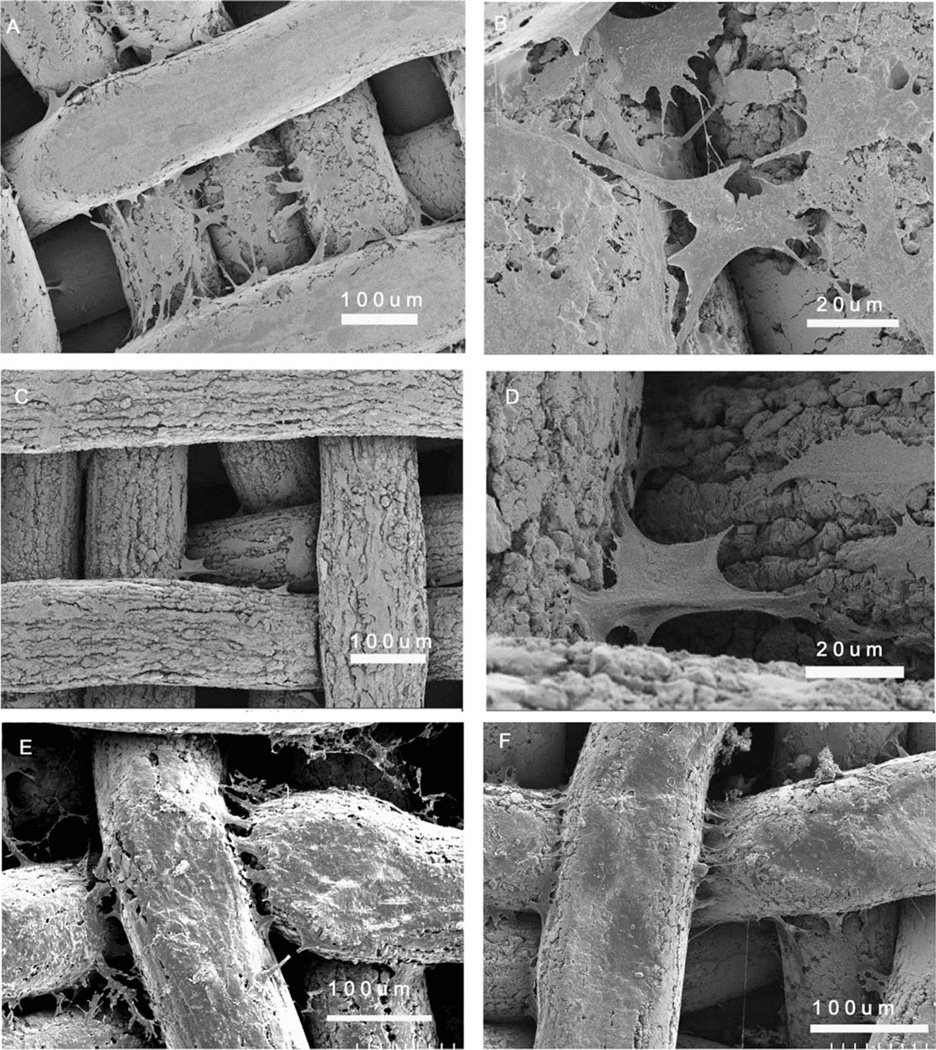

Cell morphology on 3D substrates

MG63 cells achieved confluence 5–6 days after plating. At this time point, cells on the 3D scaffolds generally acquired two types of morphology. Cells on the titanium wires had an elongated morphology [Fig. 3(A)], whereas cells that crossed the space between two or more wires anchored to different wires and had a canopy-like morphology [Fig. 3(B)]. Similar cell morphology was observed on acid etched 3D scaffolds [Fig. 3(C,D)] with lower cell density. After 12 more days of culture, cells on the 3D scaffolds populated the entire top surfaces of the titanium wire, and more cells were seen in between the wires [Fig. 3(E)]. Cells observed on the bottom of the scaffold demonstrated that proliferation into the pores had occurred [Fig. 3(F)].

FIGURE 3.

SEM images at different magnifications of the morphology of MG63 osteoblast-like cells cultured for 6 days on the 3D scaffolds (A and B) and acid-etched 3D scaffolds (C and D) and for 18 days on the top surface of 3D scaffolds (E) and bottom surface of 3D scaffolds (F).

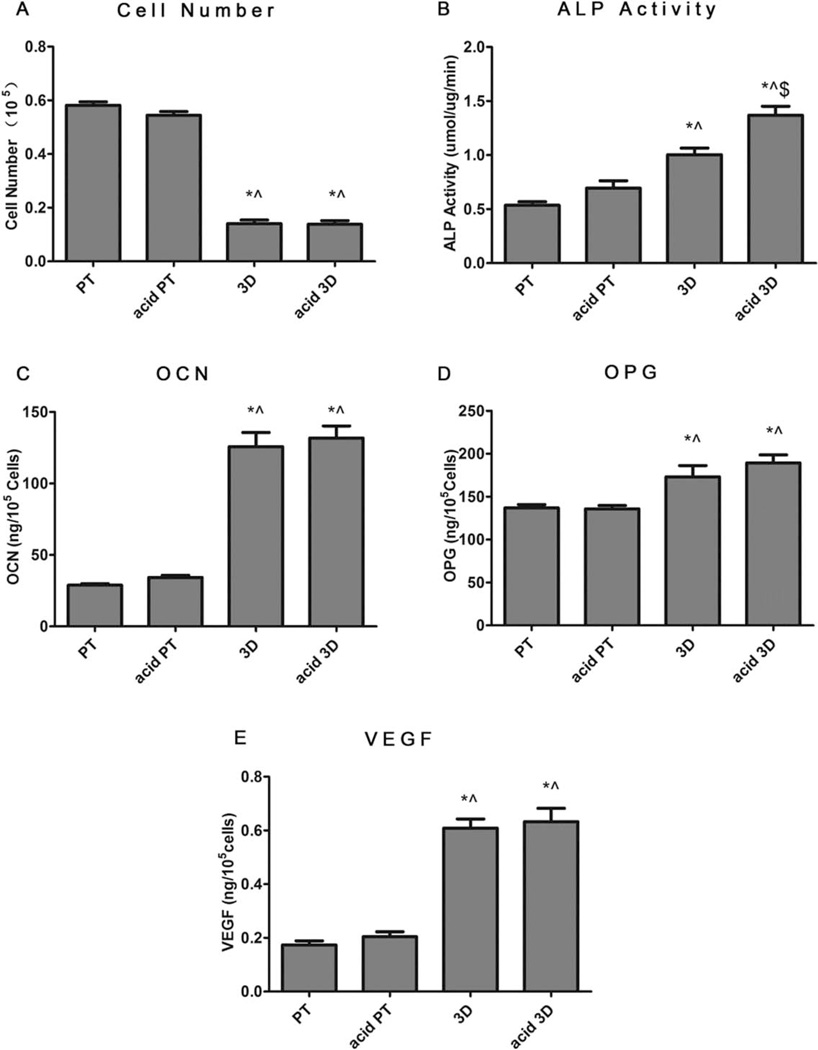

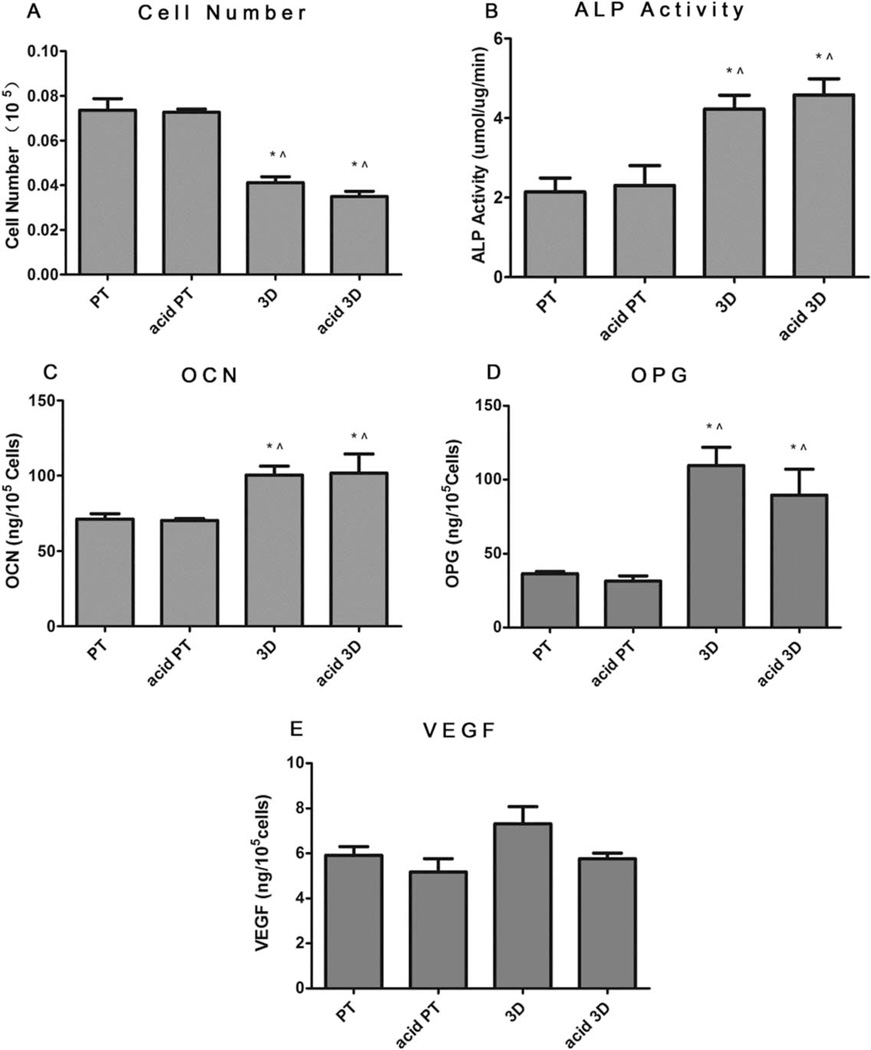

MG63 and normal human osteoblast response

Figure 4 shows the MG63 cell response on 2D surfaces (PT and acid PT) and 3D scaffolds (3D and acid etched 3D) when cells became confluent on TCPS. Cell number on both 3D substrates was lower than that on 2D surfaces, whereas no significant differences were noted before and after acid etching [Fig. 4(A)]. The production of both early and late osteoblastic differentiation markers, ALP activity [Fig. 4(B)] and OCN [Fig. 4(C)] were found to increase on the 3D and acid 3D scaffold groups, as well as the local factors OPG and VEGF [Fig. 4(D,E)]. The effect of surface roughness on MG63 differentiation was not as obvious, but the increased roughness had a positive effect on ALP activity, as significantly higher ALP activity was observed with the acid 3D group compared to the nonacid etched group.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of structural properties of 3D scaffolds combined with surface roughness modification on MG63 maturation. MG63 cells were plated on the PT, acid PT, 3D and acid 3D scaffolds and harvested at confluence on TCPS. A: Cell number, (B) ALP specific activity, (C) OCN, (D) OPG, and (E) VEGF levels were measured. Data represented are the mean ± SE of six independent samples. * refers to a statistically-significant p value below 0.05 versus PT; ^ refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus acid PT; $ refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus 3D.

Normal human osteoblast responses on 2D and 3D substrates are shown in Figure 5. Similar to MG63 cells, cell number was lower on both 3D and acid 3D groups compared to the 2D surfaces. ALP activity and levels of OCN and OPG were significantly higher on 3D and acid 3D scaffolds, whereas no difference was observed in VEGF production [Fig. 5(A–D)]. The difference in surface roughness had no effect for both 2D and 3D groups.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of structural properties of 3D microstructure combined with surface roughness modification on normal human osteoblast maturation. Normal human osteoblasts were plated and harvested at confluence on TCPS. A: Cell number, (B) ALP specific activity, (C) OCN, (D) OPG, and (E) VEGF levels were measured. Data represented are the mean ± SE of six independent samples. * refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus PT; ^ refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus acid PT.

Roles of integrin β1 and α2β1

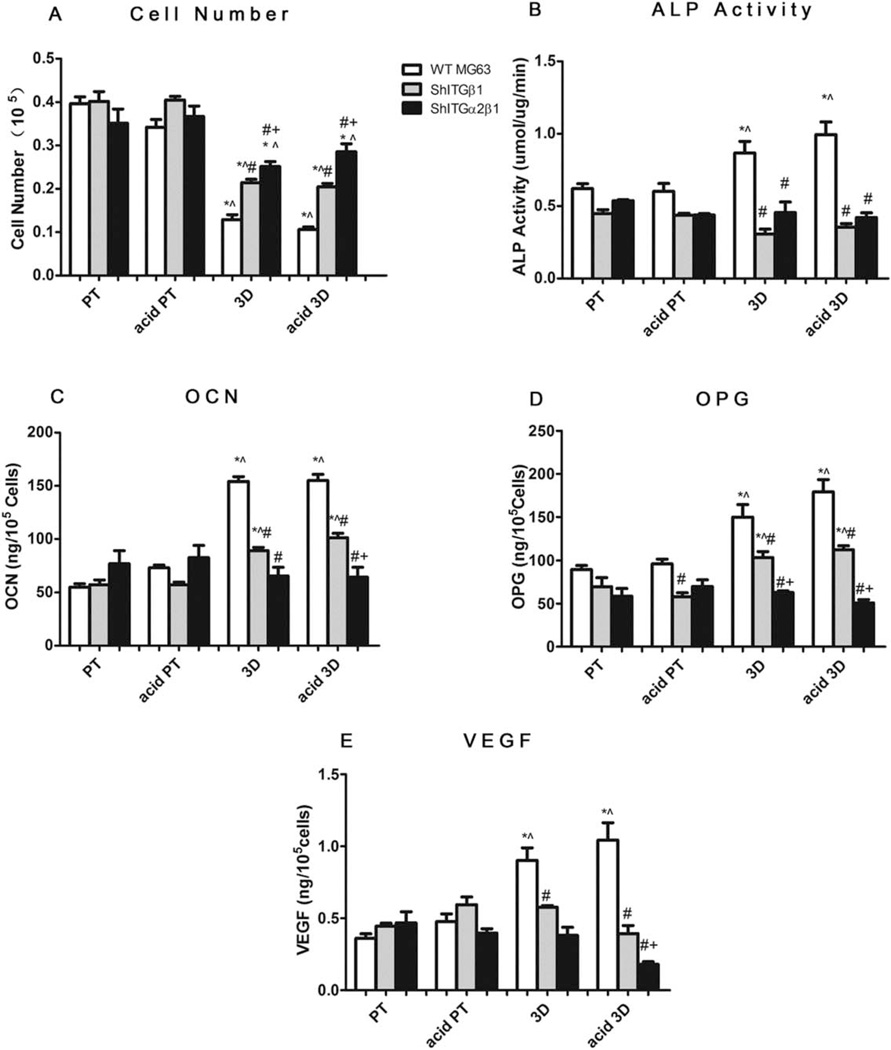

Figure 6(A–E) shows the cellular responses of wild type MG63 and silenced integrin β1 (shITG β1) and α2β1 (shITGα2β1) MG63 on 3D scaffolds. The cell numbers of all the different cell types on 3D and acid etched 3D scaffolds were lower than those on Ti surfaces [Fig. 6(A)]. When compared to the wild type MG63 cells, silencing β1 increased cell number on 3D and acid etched 3D scaffolds, but not on PT or acid etched PT surfaces; α2β1 silenced cells had the highest cell number on 3D and acid 3D scaffolds in comparison to the other two cell types on the same groups.

FIGURE 6.

Role of integrin β1 and α2 in osteoblast maturation on 3D scaffolds. MG63 cells were plated and harvested at confluence on TCPS. A: Cell number, (B) ALP specific activity, (C) OCN, (D) OPG, and (E) VEGF levels were measured. Data represented are the mean ± SE of six independent samples. * refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus PT among the same cell type; ^ refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus acid PT among the same cell type; # refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus WT MG63; + refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus shITGβ1 MG63.

The effects of integrin-silencing on osteoblastic differentiation were also surface dependent [Fig. 6(B–E)]. On PT surfaces, integrin-silencing didn’t have significant effects on the production of any of the factors tested. On acid PT surfaces, β1 silencing and α2β1 silencing reduced OPG levels. β1 silenced MG63 cells cultured on both 3D and acid 3D groups had significantly lower ALP activity [Fig. 6(B)] and OCN [Fig. 6(C)] and local factors, OPG [Fig. 6(D)] and VEGF [Fig. 6(E)], in comparison to wild type MG63 cells. α2β1 silenced cells on 3D and acid 3D scaffolds had the lowest OCN, OPG, and VEGF levels. In summary, the enhanced osteoblastic differentiation on 3D and acid 3D materials was partially blocked by β1-silencing and completely blocked by α2β1 silencing.

MG63 proliferation and differentiation on 2D and 3D substrates

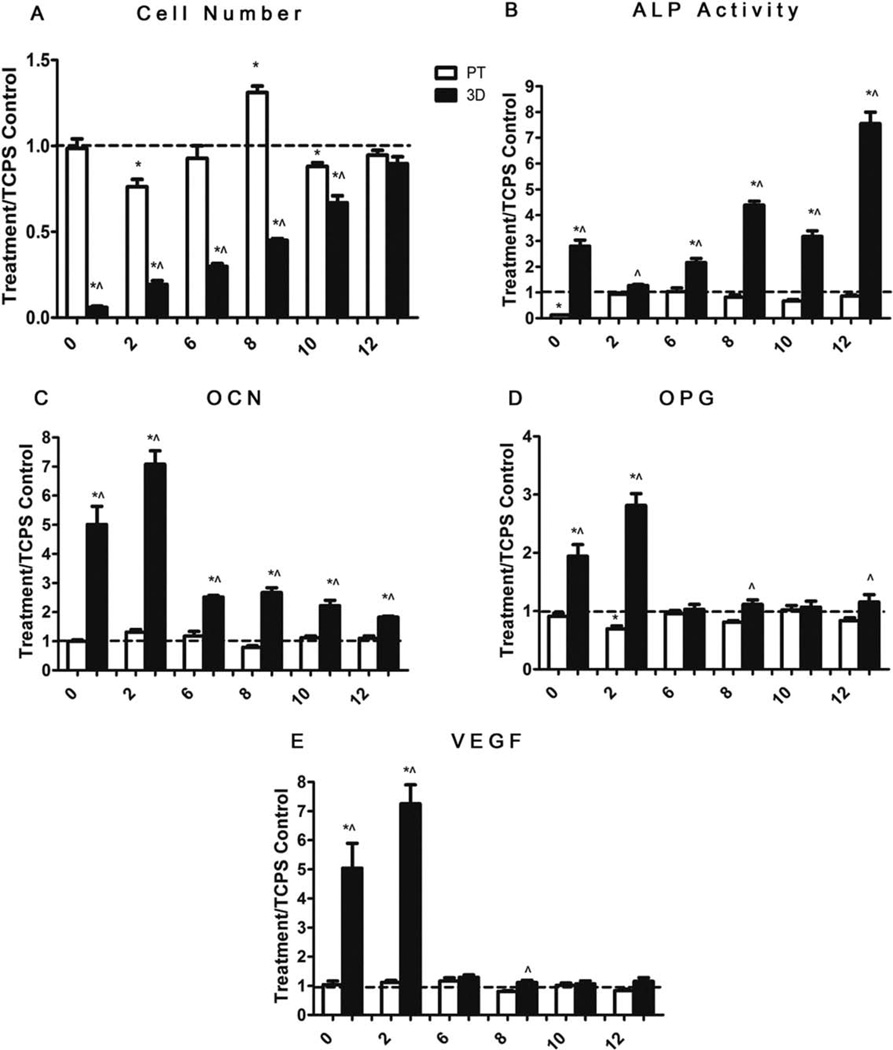

The response of MG63 cells on PT and 3D scaffolds varied with time in culture. Cell number on the 3D scaffolds was lower in the early stages of the culture, and continued to increase with time, whereas cell number on the PT surfaces peaked at day 8 postconfluence and then decreased on days 10 and 12 [Fig. 7(A)]. ALP activity [Fig. 7(B)] on 3D scaffolds increased on day 0, followed by a decrease on day 2, and an increase again on days 6, 10, and 12. OCN production [Fig. 7(C)] on 3D scaffolds was fivefold higher on day 0 and eightfold higher on day 2 postconfluence compared to PT surfaces, after which OCN production deceased to twofold to threefold higher from days 6 to 12. The local factors OPG and VEGF were significantly higher than on PT surfaces at days 0 and 2, and then decreased to comparable levels to PT surfaces [Fig. 7(D,E)].

FIGURE 7.

Effects of structural properties of 3D scaffolds on MG63 cells during culture time. MG63 were plated and the day when cells get confluence on TCPS is marked as 0. A: Cell number, (B) ALP specific activity, (C) OCN, (D) OPG, and (E) VEGF levels were measured. Data represented are the mean ± SE of six independent samples. * refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus TCPS base line; ^ refers to a statistically significant p value below 0.05 versus PT at the same time point.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a simple 3D titanium scaffold with interconnected porous structure, with or without surface roughness modification, was developed to evaluate whether 3D structures with microtexture affect growth and differentiation of osteoblasts in comparison to 2D surfaces. XPS analysis showed increased carbon contamination was increased on the acid-etched surfaces, as acid-etching increased the surface roughness and surface area, leading to more carbon trapping during autoclave sterilization. These findings are consistent with previous studies that report that acid etching increases surface oxidation and roughness, which results in more carbon trapping.42

Our results demonstrate that osteoblastic differentiation was promoted in the early stage of culture on 3D scaffolds compared to 2D surfaces. Cell number was lower whereas the production of the osteoblastic differentiation markers ALP activity and OCN, as well as local factors OPG and VEGF increased significantly on 3D scaffolds. Interestingly, in longer term cultures the number of cells continued to increase in the 3D environment and the differentiation state of the cells gradually reduced.

Laser confocal microscopy showed the interconnected pores of the 3D scaffolds with pore size big enough for cells to migrate within the scaffold. Cell morphology images showed the initial cell density was relatively low on 3D scaffolds in the early stage of culture. This result may due to the macroscale pore size of the 3D scaffolds, which may cause cells in suspension to infiltrate the scaffold without attaching during seeding. However, the macroscale pore size also allows cells to migrate and proliferate after they have attached, providing even more space for cells to grow. After culturing the cells for a longer period of time, the cells proliferated throughout the scaffolds, and filled the pores. This result was confirmed by SEM images of cell morphology at later time points during culture.

The initial osteoblast growth on 3D scaffolds compared to PT surfaces was measured by cell number of MG63 and normal human osteoblasts. Since it is hard to directly observe cells on Ti discs and scaffolds, we used TCPS as an observation control, and cells were harvested on all the different experimental groups at confluence on TCPS (5–6 days of culture).14,43,44 At this time point, there were fewer cells on the scaffolds than on the surfaces. A low initial attachment density can lead to a limited number of cell–cell contacts to form colonies. This could result in lower proliferation rates than expected.45 Although cell counts were initially lower on the 3D scaffolds, the maturation of MG63 and human osteoblasts was enhanced. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting that osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation are reversely correlated, which means when proliferation rate is high, the differentiation state is reduced.14,46,47

Previous studies have shown that titanium discs with microrough surfaces can enhance osteoblast maturation in vitro.43,48 In these studies the rough surfaces were produced by sand blasting and hydrofluoric acid etching,49 with a 1–2 µm average roughness increase compared to the smooth surfaces. In the present study, a milder acid etching process was used with an increased surface roughness by 200 nm, which is moderate in comparison to the rough Ti surfaces used previously. The results indicated that a 200-nm increase in roughness had the potential to increase ALP activity, but it was not sufficient to result in a statistically significant change in the production of OCN, OPG, and VEGF. This finding is consistent with our previously reported observations using pretreated Ti disks that were acid etched with HCl and H2SO4, resulting in a 300 nm-increase in surface roughness, but no significant increase in OCN production.38 The fact that ALP activity was higher on the acid etched 3D scaffolds in comparison to the nonetched scaffolds suggests that combining surface submicron-scale texture with 3D structure may provide environmental synergy with respect to differentiation, but to achieve a more significant change may require a more efficient method to create surface roughness other than acid-etching.

Previously, we have shown that α2 and β1 are required for osteoblast differentiation on titanium surfaces with microroughness.36,37 In addition, the roles of the different heterodimers α2β1 and α2β1 in the osteoblast maturation process were also studied in our group, and we found that the α2β1 heterodimer, which binds collagen, plays a critical role in osteoblast maturation on rough titanium surfaces. In the present study, we studied the role of integrins in osteoblast response to 3D environments. Both of the differentiation markers ALP and OCN, as well as the local factors OPG and VEGF, were partially blocked by β1 silencing and totally blocked by α2β1-silencing. β1 is able to partner with many other α-subunits, suggesting that one or more of these may have contributed to the overall result. However, the use of cells cosilenced for α2 and β1 provided less equivocal results showing that without the signaling of the α2β1 heterodimer, MG63 cells exhibited a preferentially proliferative phenotype instead of deciding to mature and produce the proteins necessary for bone mineralization.

In this study, we have found that initial cell number on 3D scaffolds was low when cell reached confluence on TCPS, which may be caused by lower cell attachment when the cells were seeded. To further examine cell proliferation on 3D scaffolds, we performed a time course study by culturing cells on 2D surfaces and 3D scaffolds for 12 days after confluence on TCPS. Although low proliferation was found on 3D scaffolds in the early stage of culture (around 5–6 days, when cells became confluence on TCPS), cells continued proliferating for the next 12 days. In contrast, on 2D surfaces the cell number peaked 8 days post confluence and had a significant decrease immediately afterward, which is consistent with previous studies showing a decrease in DNA content for osteoblasts cultured for 9 days on TCPS and polished Ti surfaces.50 These results indicate that 3D structures, which have higher surface area, can support long-term cell proliferation in vitro.

The osteoblast differentiation markers ALP activity and OCN had higher levels on 3D scaffolds compared to 2D surfaces through the entire culture time. OCN, which serves as an osteoblast late differentiation marker, was fivefold to eightfold higher on 3D scaffolds compared to 2D surfaces at days 0 and 2 “postconfluence” culture and then lessened to twofold to threefold higher from days 6 to 12, revealing that the osteoblast maturation is faster on 3D scaffolds and the enhancement effects of 3D structures could be long term with respect to our in vitro timeline. Similar effects of 3D structures on MG63 cell response were also found in OPG and VEGF. ALP activity fluctuations on 3D scaffolds can be attributed to the biphasic nature of ALP activity, which has been shown to increase in the early stage of osteoblast differentiation followed by a decrease when the maturing osteoblasts start producing other proteins involved in mineralization such as OCN.51 With the continued cell proliferation and differentiation on 3D scaffolds, ALP activity might have gone up and down alternately throughout the cell culture period. However, ALP activity at 12 days postconfluence was still at very high level, indicating further differentiation potential. Taking these in vitro results together, 3D porous scaffolds seem to provide osteoblasts with a more robust environment to commence differentiation in the early stages of culture and might be able to support differentiation in a longer period of time.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we have evaluated the effect of porous 3D Ti scaffolds on osteoblast maturation and the critical role of integrin β1 and α2β1 in the maturation process. MG63 osteoblast-like cells and human osteoblasts were sensitive to the 3D structure. The 3D structure enhanced osteoblast maturation, as all 3D groups had lower cell numbers and higher levels of differentiation markers compared to 2D Ti surfaces, and ALP activity responded to surface roughness within a 3D environment. The silencing of integrin β1 partially abolished and α2β1 completely abolished the structural effects of the 3D structure and the surface roughness, indicating that the integrin β1 subunit and α2β1 heterodimer play critical roles during the maturation of MG63 cells. Osteoblasts on 3D scaffolds matured faster than those on 2D surfaces. Overall, our study shows that 3D titanium scaffolds can be used as a promising design for dental and bone implants for clinical and tissue engineering applications. Surface roughness on 3D scaffolds showed a potential synergistic effect on ALP activity, and the scale of surface roughness should be properly designed to achieve more significant enhancement of osteoblast maturation and local factor production.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Basic Research Program of China; contract grant number: 2012CB933903

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; contract grant number: AR052102

Contract grant sponsor: Wallace H. Coulter Foundation and a fellowship from the Panamanian Government (IFARHU-SENACYT; to RAG)

REFERENCES

- 1.Vannoort R. Titanium—The implant material of today. J Mater Sci. 1987;22:3801–3811. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokubo T, Yamaguchi S. Bioactive Ti metal and its alloys prepared by chemical treatments: State-of-the-Art and future trends. Adv Eng Mater. 2010;12:B579–B591. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanford CM, Keller JC. The concept of osseointegration and bone matrix expression. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:83–101. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanzillotta PS, Sader MS, Bastos IN, Soares GD. Improvement of in vitro titanium bioactivity by three different surface treatments. Dent Mater. 2006;22:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legeros RZ, Craig RG. Strategies to affect bone remodeling— Osteointegration. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:S583–S596. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu XY, Chu PK, Ding CX. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng Res. 2004;24(47):49–121. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao G, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Rupp F, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. High surface energy enhances cell response to titanium substrate microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2005;74:49–58. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He P, Feng JC, Zhang BG, Qian YY. Microstructure and strength of diffusion-bonded joints of TiAl base alloy to steel. Mater Char-act. 2002;48:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deligianni DD, Katsala N, Ladas S, Sotiropoulou D, Amedee J, Missirlis YF. Effect of surface roughness of the titanium alloy Ti-6AI-4V on human bone marrow cell response and on protein adsorption. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lincks J, Boyan BD, Blanchard CR, Lohmann CH, Liu Y, Cochran DL, Dean DD, Schwartz Z. Response of MG63 osteoblast-like cells to titanium and titanium alloy is dependent on surface roughness and composition. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2219–2232. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khang D, Choi J, Im YM, Kim YJ, Jang JH, Kang SS, Nam TH, Song J, Park JW. Role of subnano-, nano- and submicron-surface features on osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5997–6007. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balla VK, Bodhak S, Bose S, Bandyopadhyay A. Porous tantalum structures for bone implants: Fabrication, mechanical and in vitro biological properties. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3349–3359. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda A, Takemoto M, Saito T, Fujibayashi S, Neo M, Pattanayak DK, Matzushita T, Sasaki K, Nishida N, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Osteoinduction of porous Ti implants with a channel structure fabricated by selective laser melting. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2327–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gittens RA, McLachlan T, Olivares-Navarrete R, Cai Y, Berner S, Tannenbaum R, Schwartz Z, Sandhage KH, Boyan BD. The effects of combined micron-/submicron-scale surface roughness and nanoscale features on cell proliferation and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3395–3403. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annunziata M, Oliva A, Buosciolo A, Giordano M, Guida A, Guida L. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell response to nano-structured oxidized and turned titanium surfaces. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:733–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, Tanzer M, Krygier JJ. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:907–914. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b5.9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook SD, Thomas KA, Dalton JE, Volkman TK, Whitecloud TS, Kay JF. Hydroxylapatite coating of porous implants improves bone ingrowth and interface attachment strength. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:989–1001. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820260803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens B, Yang YZ, MohandaS A, Stucker B, Nguyen KT. A review of materials, fabrication to enhance bone regeneration in methods, and strategies used engineered bone tissues. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2008;85:573–582. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhari A, Braem A, Vleugels J, Martens JA, Naert I, Cardoso MV, Duyck J. Bone tissue response to porous and functionalized titanium and silica based coatings. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujibayashi S, Takemoto M, Neo M, Matsushita T, Kokubo T, Doi K, Ito T, Shimizu A, Nakamura T. A novel synthetic material for spinal fusion: a prospective clinical trial of porous bioactive titanium metal for lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:1486–1495. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Q, Saiz E, Rahaman MN, Tomsia AP. Bioactive glass scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future perspectives. Mater Sci Eng C: Mater. 2011;31:1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okumura T, Gonda Y, loku K, Kamitakahara M, Okuda T, Yonezawa I, Kurosawa H, Asahina I, Ikeda T. Behavior of beta-tricalcium phosphate granules composed of rod-shaped particles in the rat tibia. J Ceram Soc Jpn. 2011;119:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedraza E, Brady AC, Fraker CA, Stabler CL. Synthesis of macroporous poly(dimethylsiloxane) scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2013;24:1041–1056. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2012.735097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neman J, Hambrecht A, Cadry C, Goodarzi A, Youssefzadeh J, Chen MY, Jandial R. Clinical efficacy of stem cell mediated osteogenesis and bioceramics for bone tissue engineering. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;760:174–187. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4090-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Zhu J, Yin L, Liu S, Zhang X, Ao Y, Chen H. Fabrication of electrospun silica-titania nanofibers with different silica content and evaluation of the morphology and osteoinductive properties. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100:3511–3517. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang WJ, Li ZH, Liu Y, Ye DX, Li JH, Xu LY, Wei B, Zhang X, Liu X, Jiang X. Biofunctionalization of a titanium surface with a nanosawtooth structure regulates the behavior of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:4459–4472. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S33575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusmanto F, Walker G, Gan Q, Walsh P, Buchanan F, Dickson G, McCaigue M, Dring MM. Development of composite tissue scaffolds containing naturally sourced mircoporous hydroxyapatite. Chem Eng J. 2008;139:398–407. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Gittens RA, Song R, Tannenbaum R, Olivares-Navarrete R, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Effects of structural properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofiber meshes on their osteogenic potential. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galante J, Rostoker W. Fiber metal composites in the fixation of skeletal prosthesis. J Biomed Mater Res. 1973;7:43–61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khor KA, Gu YW, Pan D, Cheang P. Microstructure and mechanical properties of plasma sprayed HA/YSZ/Ti-6AI-4V composite coatings. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4009–4017. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espana FA, Balla VK, Bose S, Bandyopadhyay A. Design and fabrication of CoCrMo alloy based novel structures for load bearing implants using laser engineered net shaping. Mater Sci Eng C: Mater. 2010;30:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gronthos S, Stewart K, Graves SE, Hay S, Simmons PJ. Integrin expression and function on human osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1189–1197. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyan BD, Lohmann CH, Dean DD, Sylvia VL, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z. Mechanisms involved in osteoblast response to implant surface morphology. Ann Rev Mater Res. 2001;31:357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia AJ, Vega MD, Boettiger D. Modulation of cell proliferation and differentiation through substrate-dependent changes in fibronectin conformation. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:785–798. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Gittens RA, Schneider JM, Haithcock DA, Ullrich PF, Slods PJ, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Rough titanium alloys regulate osteoblast production of angiogenic factors. Spine J. 2013;13:1563–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang LP, Zhao G, Olivares-Navarrete R, Bell BF, Wieland M, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Integrin beta(1) silencing in osteoblasts alters substrate-dependent responses to 1,25-dihy-droxy vitamin D-3. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3716–3725. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivares-Navarrete R, Raz P, Zhao G, Chen J, Wieland M, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Integrin alpha 2 beta 1 plays a critica role in osteoblast response to micron-scale surface structure and surface energy of titanium substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15767–15772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805420105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyan BD, Batzer R, Keiswetter K, Liu Y, Cochran DL, Szmuckler-Moncler S, Dean DD, Schwartz Z. Titanium surface roughness alters responsiveness of MG63 osteoblast-like cells to 1α,25-(OH)2D3. J Bio Med Mater Res. 1998;39:77–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199801)39:1<77::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park JH, Olivares-Navarrete R, Baier RE, Meyer AE, Tannenbaum R, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Effect of cleaning and sterilization on titanium implant surface properties and cellular response. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:1966–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W, Zhao L, Ma Q, Wang Q, Chu PK, Zhang Y. The role of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in the effect of implant topography on MG63 differentiation. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7993–8002. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothem DE, Rothem L, Dahan A, Eliakim R, Soudry M. Nicotinic modulation of gene expression in osteoblast cells MG-63. Bone. 2011;48:903–909. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Guehennec L, Lopez-Heredia MA, Enkel B, Weiss P, Amouriq Y, Layrolle P. Osteoblastic cell behaviour on different titanium implant surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyan BD, Batzer R, Kieswetter K, Liu Y, Cochran DL, Szmuckler-Moncler S, Dean DD, Schwartz Z. Titanium surface roughness alters responsiveness of MG63 osteoblast-like cells to 1 alpha,25-(OH)(2)D-3. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39:77–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199801)39:1<77::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang XK, Gittens RA, Song R, Tannenbaum R, Olivares-Navarrete R, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Effects of structural properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofiber meshes on their osteogenic potential. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heng BC, Bezerra PP, Preiser PR, Law SKA, Xia Y, Boey F, Venkatraman SS. Effect of cell-seeding density on the proliferation and gene expression profile of human umbilical vein endothelial cells within ex vivo culture. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:606–617. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.542455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lohmann CH, Schwartz Z, Liu Y, Guerkov H, Dean DD, Simon B, Boyan BD. Pulsed electromagnetic field stimulation of MG63 osteoblast-like cells affects differentiation and local factor production. J Ortho Res. 2000;18:637–646. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lan MA, Gersbach CA, Michael KE, Keselowsky BG, Garcia AJ. Myoblast proliferation and differentiation on fibronectin-coated self assembled monolayers presenting different surface chemistries. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4523–4531. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hakki SS, Bozkurt SB, Hakki EE, Korkusuz P, Purali N, Koc N, Timucin M, Ozturk A, Korkusuz F. Osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells on different titanium surfaces. Biomed Mater. 2012;7 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/7/4/045006. 045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sahafi A, Peutzfeldt A, Asmussen E, Gotfredsen K. Bond strength of resin cement to dentin and to surface-treated posts of titanium alloy, glass fiber, and zirconia. J Adhes Dent. 2003;5:153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.St-Pierre JP, Gauthier M, Lefebvre LP, Tabrizian M. Three-dimensional growth of differentiating MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts on porous titanium scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7319–7328. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lian JB, Stein GS. Concepts of osteoblast growth and differentiation—Basis for modulation of bone cell-development and tissue formation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1992;3:269–305. doi: 10.1177/10454411920030030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]