Abstract

Purpose

There are growing concerns regarding the overtreatment of localized prostate cancer. It is also relatively unknown whether there has been increased uptake of observational strategies for disease management. We assessed the temporal trend in use of observation for clinically localized prostate cancer, particularly among men with low-risk disease, who were young and healthy enough to undergo treatment.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registry linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare database) in 66,499 men with localized prostate cancer between 2004 and 2009. The main outcome was use of observation within one year following diagnosis. We performed multivariable analysis to develop a predictive model for use of observation adjusting for diagnosis year, age, risk and comorbidity.

Results

Observation was used in 12,007 men (18%) with a slight increase over time from 17% to 20%. However, there was marked increase in the use of observation from 18% in 2004 to 29% in 2009 for men with low-risk disease. Men 66–69 years old, with low-risk disease and no comorbidities, had twice the odds of undergoing observation in 2009 versus 2004 (OR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.73–2.59). In addition to the diagnosis year, age, risk group, comorbidity and race were independent predictors of undergoing observation (all P<.001).

Conclusions

We identified increasing use of observation for low-risk prostate cancer between 2004 and 2009, even among men young and healthy enough for treatment, suggesting growing acceptance of surveillance in this group of patients.

Keywords: prostate cancer, observation, active surveillance, watchful waiting, low-risk

Introduction

Although prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States, localized prostate cancer is often not life threatening, particularly in patients with competing risks for other-cause mortality.1,2 Low-risk disease, which accounts for up to 40% of new diagnoses, has excellent cancer-specific survival even when managed conservatively.3–5 However, over 90% of men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer have sought treatment, even patients at low risk for prostate cancer mortality.6–8

The ‘over-treatment’ of low-risk prostate cancer has resulted in a significant burden by exposing patients to the harms and costs of unnecessary therapy. In response to concerns regarding over-treatment, observational strategies are being promoted for older, infirm men with competing risks for mortality, as well as younger, healthier men with low-risk disease. Despite the emerging evidence, it is not clear that healthcare providers and patients in the US have accepted observation as a legitimate form of disease management.

Increased utilization of observational strategies among patients at low risk for prostate cancer mortality could have an enormous impact on the burden of treatment-related morbidity and cost of care. For these reasons, we sought to determine the temporal trends in the use of observation, with respect to disease risk, age and comorbidity, in a population-based cohort of men in the US, diagnosed with localized prostate cancer between 2004 and 2009. Of note, we defined observation as the absence of primary treatment within one year of diagnosis as the current dataset does not distinguish between types of observational strategies i.e active surveillance (AS) or watchful waiting (WW). We hypothesized that there would be an increase in the use of observation over time, particularly in men with low-risk disease, even among men young and healthy enough to undergo treatment.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

Data from the Surveillance Epidemiology, and End results (SEER) population based cancer registry linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare database) were used to conduct the study. SEER incorporates patient data in select geographic regions covering approximately 26% of the US population and the Medicare claims database covers approximately 95% of patients age 65 years and older.9 The linkage of SEER-Medicare files is complete for approximately 93% of patients. The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Using the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) file, the National Claims History (NCH) file, and the outpatient claims file linked to the SEER Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary (PEDSF) file we identified 170,869 men aged 66 years and older who were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the prostate between 2004 and 2009. Men who were diagnosed upon death or autopsy analysis were excluded. To ensure complete records, we also excluded men without continuous Medicare Part A and Part B insurance coverage for one year before and two years after diagnosis, as well as those enrolled in Medicare Advantage at any time during the study period. We then excluded men with locally advanced (T4), and/or metastatic (N1, M1) disease based on the 2006 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system. We also excluded those with PSA > 50ng/ml as they may potentially harbor occult metastatic disease. Patients incidentally diagnosed by radical cystoprostatectomy were also excluded. All included patients had at least one documented diagnostic prostate biopsy during the study period. (Supplement Figure 1)

Definition of Outcome

Our primary outcome measure was the use of observation as the initial management for clinically localized (cT1–3, N0, M0) prostate cancer. Using relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, we identified and defined primary treatment as: surgery (radical prostatectomy), radiotherapy (either external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy), cryoablation and primary androgen deprivation therapy (PADT). PADT was defined as either receiving luteinizing hormone receptor agonists, antagonists and/or anti-androgens, or surgical castration. Men were considered to have undergone observation if they received none of the above therapies within one year of diagnosis. (Supplement Table 1)

Definitions of Exposures of Interest

Our primary exposure of interest was time, defined as calendar year of prostate cancer diagnosis (2004–2009). We hypothesized that the association between observation and time would be modified by the following characteristics: age, race, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI – age unadjusted), and D’Amico risk group. These four variables were our secondary exposures of interest. We categorized age by groups: 66–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years old. CCI was calculated using a previously described algorithm and categorized as 0, 1–2 and ≥3.10 The D’Amico classification was used to define prostate cancer risk groups.2 Race was defined as White, Black, and Other (including Asian, Hispanic, North American Native).

Definition of Covariates

Potential confounding variables included median income of census tract (2000 US Census), marital status, and geographic region. We categorized median income as: ≤ $38,897, $38,898 to $56,002, and > $56,002. We defined marital status as married or unmarried (including single, divorced, widowed, or separated). SEER geographic areas included North Central, Northeast, South, and West.

Statistical Analysis

We described our analytic cohort by producing frequencies and percentages of demographic and health characteristics. To assess the association between observation and year of diagnosis, we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis with year of diagnosis as the primary exposure. We also included secondary exposures known to affect use of observation including age, CCI, D’Amico risk, and race.11 Additionally, we adjusted for median income, marital status, and geographic region, and we included all two-level interactions between exposures of interest. We performed multiple imputation using predictive mean matching during modeling in order to assign values to missing exposures and covariates. Odds ratios are interpreted as being among set values of all other variables with which it is interacted. These set values are: year of diagnosis=2009, age group=66–69 years, risk group=low, CCI group=0, and race=white (eg. odds ratios for year of diagnosis are interpreted among white men aged 66–69 years who have low-risk disease and CCI=0).

The relationship between use of observation and year of diagnosis by age, comorbidity and risk group, was demonstrated by plotting the predicted probability of observation from our model across time by age, CCI, and risk group. We also performed a sub-analysis by race to assess whether time trends in use of observation were consistent across racial groups. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2 and R packages Hmisc, rms, and ggplot2.12–15 All P-values were two-sided, and P-values ≤ .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Our final analytic cohort consisted of 66,499 men with clinically localized prostate cancer. (Table 1) Most patients were white (83%), 70–79 years old (57%) and relatively healthy (88% with CCI=0–2). In terms of risk stratification, 34% of patients were classified as low-risk, 40% intermediate-risk and 26% high-risk. The proportion of patients diagnosed annually ranged from 15% to 16% over the period 2004–2007 and increased to 19% and 18% in 2008 and 2009 respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and health characteristics of men with localized prostate cancer

| Characteristic | N = 66,499 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age Group | |

| 66–69 | 18,111 (27) |

| 70–79 | 37,775 (57) |

| 80–89 | 10,613 (16) |

| Risk Group† | |

| Low | 19,105 (34) |

| Intermediate | 22,591 (40) |

| High | 14,394 (26) |

| CCI Group | |

| 0 | 31,525 (47) |

| 1–2 | 27,041 (41) |

| ≥3 | 7,933 (12) |

| Race | |

| White | 55,096 (83) |

| Black | 7,392 (11) |

| Asian | 1,453 (2) |

| Hispanic | 980 (1) |

| Other | 1413 (2) |

| North American Native | 117 (<1) |

| Tertiles of Median Income of Census Tract‡ | |

| ≤$38,897 | 20,994 (33) |

| $38,898–$56,002 | 20,985 (33) |

| ≥$56,003 | 21,009 (33) |

| Marital Status¥ | |

| Unmarried | 12,407 (21) |

| Married | 45,303 (79) |

| Geographic Region | |

| West | 22,526 (34) |

| North Central | 7,468 (11) |

| Northeast | 16,533 (25) |

| South | 19,972 (30) |

| Year of Diagnosis | |

| 2004 | 10,587 (16) |

| 2005 | 9,865 (15) |

| 2006 | 10,609 (16) |

| 2007 | 10,964 (16) |

| 2008 | 12,765 (19) |

| 2009 | 11,709 (18) |

N=56,090

N=62,988

N=57,710 due to missing values in SEER Medicare dataset. Missing values were multiply imputed at the point of modeling.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index

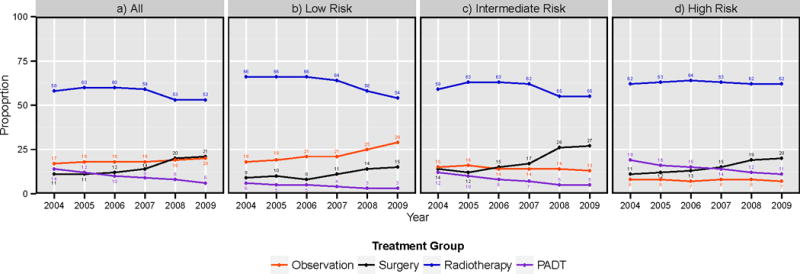

Observation was used in 12,007 (18%) patients and treatment occurred in 54,492 (82%) patients. Radiotherapy was the most common treatment modality (54%) followed by surgery (15%), PADT (10%) and cryoablation (3%). The use of observation among all patients remained stable at 17–18% from 2004 to 2007 followed by a slight increase from 2007 to 2009 (18% to 20%). The proportion of patients who underwent surgery increased steadily from 11% in 2004 to 21% in 2009. Radiotherapy use was stable at around 60% from 2004 to 2007 and then declined to 53% thereafter. The use of PADT decreased steadily from 14% to 8% over the study period. (Figure 1a) Given that disease risk plays a role in treatment decisions, we compared the proportion of men undergoing each treatment by risk group. (Figure 1b–d) This stratification clearly demonstrated that the main driver for the increased use of observation over time was the increased utilization in low-risk patients. The proportion of low-risk patients who underwent observation grew steadily from 18% in 2004 up to 29% in 2009.

Figure 1.

Trend in utilization of observation and treatment for localized prostate cancer a) for all patients, and b) for low, c) intermediate and d) high risk disease

Abbreviations: PADT, primary androgen deprivation therapy

Table 2 shows associations between use of observation and main variables in our multivariable model. We found that there was a significant increase in the likelihood of undergoing observation over time (P<.001). Among white men aged 66–69 years with low risk disease and CCI=0, those who were diagnosed in 2009 had more than twice the odds of undergoing observation relative to men who were diagnosed in 2004 (OR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.73–2.59). We found that age, risk, CCI, and race were all significantly associated with observation (P<.001). Men who were older, had low-risk disease and a higher number of comorbidities, had a significantly higher odds of being observed. In addition, black race was a significant predictor of undergoing observation (P<.001).

Table 2.

Effect of age, risk group, Charlson comorbidity index, year of diagnosis, and race on observation in men with localized prostate cancer†

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis‡ | |||

| 2004 (ref) | — | — | |

| 2005 | 1.42 | 1.15–1.76 | |

| 2006 | 1.39 | 1.12–1.71 | <.001 |

| 2007 | 1.47 | 1.19–1.81 | |

| 2008 | 1.69 | 1.38–2.05 | |

| 2009 | 2.12 | 1.73–2.59 | |

| Age Group¥ | |||

| 66–69 (ref) | — | — | |

| 70–79 | 1.73 | 1.08–2.00 | <.001 |

| 80–89 | 6.02 | 4.88–7.43 | |

| Risk Group€ | |||

| Low | 5.37 | 4.25–6.77 | |

| Intermediate | 1.72 | 1.35–2.18 | <.001 |

| High (ref) | — | — | |

| CCI Group£ | |||

| 0 (ref) | — | — | |

| 1–2 | 0.94 | 0.81–1.09 | <.001 |

| ≥3 | 1.38 | 1.10–1.73 | |

| Race§ | |||

| White (ref) | — | — | |

| Black | 1.28 | 1.03–1.61 | <.001 |

| Other | 1.32 | 0.98–1.79 |

Multivariable logistic regression model with a-priori selected exposures of interest: age, risk group, CCI, year of diagnosis, and race and adjusted for median income of census tract, marital status, geographic region as well as all two-level interactions between exposures of interest. The odds ratios are shown for each level of main exposure variables, while other variables are held constant

Year = 2009;

age group =60–69;

risk group = low;

CCI group = 0;

race = white).

P-values for main effects test whether the main variable or any interaction term containing the main variable equals 0.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; CCI=Charlson Comorbidity Index

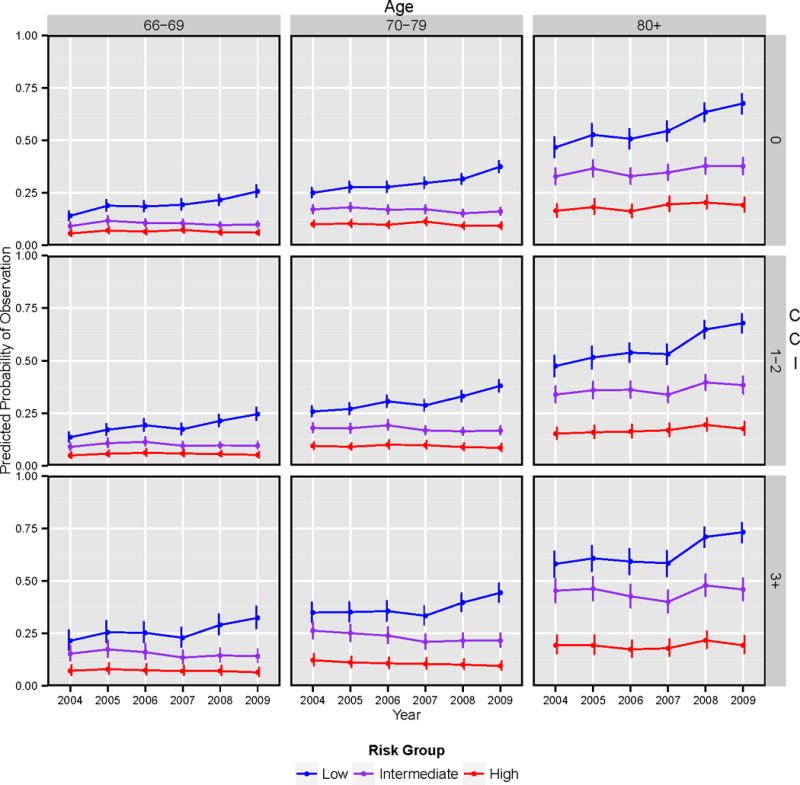

Figure 2 displays predicted probability of observation across time by risk group, age, and CCI, based on the multivariable model. In all groups, the predicted probability of undergoing observation among low-risk patients increased over time whereas for intermediate and high-risk patients it was relatively stable. A significant interaction existed between year of diagnosis and risk group indicating that the effect of observation over time varied by risk (P<.001). For younger, healthy men with low-risk disease, there was a notably higher probability of undergoing observation in 2009 (25%) compared to 2004 (15%). For men in all risk groups, use of observation increased over time with age (P<.001). In contrast, use of observation over time did not vary significantly by CCI (P=0.23). For example, in 2009, the predicted probability of observation in low-risk men aged 66–69 years with CCI = 0 was 25% compared to 70% for men aged ≥80 years with CCI = 0, but only 30% for those aged 66–69 years and CCI = 3+. As expected, patients who were oldest and sickest had the highest predicted probability of undergoing observation across all risk groups.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of undergoing observation for localized prostate cancer by risk group, age group, CCI group, and year of diagnosis†.

†Predicted probabilities are computed with other variables in the model set to the following values: race = white, marital status = married, region = Western region, and median income of census tract = $38,898–$56,002.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index

Sub-analysis across racial groups revealed that among low-risk men aged 66–69 years and CCI=0 in 2009, black men were more likely to undergo observation than white men (OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.03–1.61). However, although the overall use of observation was higher in black patients, the trend in utilization from 2004 to 2009 was similar to white patients (P=0.77), indicating that the pattern of observation seen in the study population is similar between racial groups. (Supplement Figure 2)

Discussion

While there are mounting data to support observational strategies in prostate cancer, historical rates have been less than 10%.6,16 We have shown that among patients 66 years and older, the use of observation increased significantly from 2004 to 2009, mainly in those with low-risk disease. As expected, the use of observation was also higher in older men and those with more comorbidities. However, the increase in use of observation over time was not restricted to older men, which suggests that there may be growing acceptance of observation in younger men with low-risk disease.

The last decade has been an influential period in the management of localized prostate cancer.5,17,18 National guidelines recommend consideration of observation for men with low-risk disease, and those with a limited life expectancy.19,20 Few studies have assessed how observation is being applied with respect to overall uptake and the influence of factors such as age, comorbidity and disease risk. Data from a contemporary cohort of 11,892 men demonstrate that the use of observation among all risk groups was 6.8%.16 However, the study did not determine in whom observation was most likely to be used. Other studies have shown that age and risk stratum predict use of observation, but these findings are not adjusted for comorbidities or other determinants of life expectancy.6 Filson et al reported that there was increased use of observation over time with significant variation by healthcare region.21 Their study corroborates some of our findings, but the analysis did not extend beyond 2007, which was the point at which we found a significant rise in the use of observation. While the focus on variation by region is relevant for understanding the influence of local market forces on treatment decisions, our study is unique in demonstrating a convincing, growing association between clinically relevant patient characteristics and the use of observation.

Interestingly, age appeared to have a greater effect on use of observation than comorbidity. Available data demonstrate that comorbidity is a strong predictor of other-cause mortality among men with prostate cancer.22 Yet our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that providers are more apt to consider the influence of age as opposed to comorbidity when deciding on treatment options.8 Increasing awareness of the influence of comorbidity on other-cause mortality, and tools to integrate comorbidity burden into decision-making may facilitate the uptake of observation.

Similar to other studies, we also found that black race predicted an increased likelihood of observation.23–26 The reason for this difference may be due to a combination of factors such as patient preference, provider factors, socioeconomic status and access to care.26 Although the overall use of observation is higher in black patients, our study indicates that the rate of increase among low-risk patients is similar regardless of race.

The current study, although strong with respect to the large sample size, is not without limitations. First, our definition of observation (absence of treatment within one year of diagnosis) does not distinguish between the passive approach of WW, and the more involved approach of AS. However, both practices entail a purposeful decision to observe the patient, based on clinical characteristics. Thus, while the intent of observation cannot be discerned from this dataset, we found an increase in use of observation both among men with limited life-expectancy who are candidates for WW, and among men with low-risk disease and a long life-expectancy, who are candidates for AS. While we show that use of observation is associated with evidence-based clinical factors, the available data are not sufficiently granular to determine whether individual patients were appropriately selected for observation or whether the intensity of their surveillance was matched to the modality of observation. Second, the age of Medicare beneficiaries is 65 years and older therefore these findings may not be applicable to younger patients. Nonetheless, the average age at diagnosis of localized prostate cancer is approximately 64 years so our study is representative for a large proportion of men.27 Third, we were unable to control for patient preference due to data limitations. Finally, we were limited by the time period in SEER-Medicare data, which lacks exact PSA values prior to 2004, and currently extends only up to 2009.

These limitations notwithstanding, we have demonstrated an increase in the use of observation in the management of clinically localized prostate cancer over time, driven in large part by increased observation of low-risk disease in all strata of age and comorbidity. These findings suggest that there has been a growing acceptance of observation and an ‘un-coupling’ of treatment from diagnosis, both for patients with competing causes of mortality, and those with low-risk prostate cancer who are young and healthy enough for treatment. Utilization of observation will have to expand further in order to improve the benefit-to-harm ratio of prostate cancer detection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Brent Hollenbeck, Dr. Bruce Jacobs and Dr. Florian Schroeck from the University of Michigan, Department of Urology and Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, for providing coding algorithms used in the development of the study cohort.

Funding/Support: Dr. Keegan was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, K-12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology, CA-90625

Dr. Barocas is supported by a National Cancer Institute R-03 award (Grant # 1R03CA173812-01)

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:2095–101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. JAMA. 2009;302:1202–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, et al. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:126–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barocas DA, Cowan JE, Smith JA, Jr, et al. What percentage of patients with newly diagnosed carcinoma of the prostate are candidates for surveillance? An analysis of the CaPSURE database. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:1330–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.019. discussion 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, et al. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:2141–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daskivich TJ, Chamie K, Kwan L, et al. Overtreatment of men with low-risk prostate cancer and significant comorbidity. Cancer. 2011;117:2058–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical care. 2002;40:IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2000;53:1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harlan SR, Cooperberg MR, Elkin E, et al. Time trends and characteristics of men choosing watchful waiting for initial treatment of localized prostate cancer: results from CaPSURE. The Journal of urology. 2003;170:1804–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091641.34674.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. at http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R package version 3.12-2. 2013 at http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc.

- 14.rms: Regression Modeling Strategies. R package version 4.0-0. 2013 at http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms.

- 15.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Carroll PR. Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1117–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:932–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:203–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. The Journal of urology. 2007;177:2106–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohler JL, Kantoff PW, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate cancer, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1471–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filson CP, Schroeck FR, Ye Z, et al. Variation in use of active surveillance among men undergoing expectant management for early-stage prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.105. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daskivich TJ, Fan KH, Koyama T, et al. Effect of age, tumor risk, and comorbidity on competing risks for survival in a U.S. population-based cohort of men with prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:709–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton AS, Albertsen PC, Johnson TK, et al. Trends in the treatment of localized prostate cancer using supplemented cancer registry data. BJU international. 2011;107:576–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeliadt SB, Potosky AL, Etzioni R, et al. Racial disparity in primary and adjuvant treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer: SEER-Medicare trends 1991 to 1999. Urology. 2004;64:1171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman RM, Harlan LC, Klabunde CN, et al. Racial differences in initial treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2003;18:845–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shavers VL, Brown ML, Potosky AL, et al. Race/ethnicity and the receipt of watchful waiting for the initial management of prostate cancer. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004;19:146–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass AS, Cowan JE, Fuldeore MJ, et al. Patient demographics, quality of life, and disease features of men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer: trends in the PSA era. Urology. 2013;82:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.