SUMMARY

The adaptability and survival of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the oxidative microenvironment of the periodontal pocket are indispensable for survival and virulence, and are modulated by multiple systems. Among the various genes involved in P. gingivalis oxidative stress resistance, vimA gene is a part of the 6.15-kb locus. To elucidate the role of a P. gingivalis vimA-defective mutant in oxidative stress resistance, we used a global approach to assess the transcriptional profile, to study the unique metabolome variations affecting survival and virulence in an environment typical of the periodontal pocket. A multilayered protection strategy against oxidative stress was noted in P. gingivalis FLL92 with upregulation of detoxifying genes. The duration of oxidative stress was shown to differentially modulate transcription with 94 (87%) genes upregulated twofold during 10 min and 55 (83.3%) in 15 min. Most of the up-regulated genes (55%), fell in the hypothetical/unknown/unassigned functional class. Metabolome variation showed reduction in fumarate and formaldehyde, hence resorting to alternative energy generation and maintenance of a reduced metabolic state. There was upregulation of transposases, genes encoding for the metal ion binding protein transport and secretion system.

Keywords: molecular, oral microbiology, porphyromonas

INTRODUCTION

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a black-pigmented, gram-negative anaerobe, is an important etiological agent of periodontal disease (reviewed in Lamont & Jenkinson, 1998; Hajishengallis et al., 2011; Darveau et al., 2012; Tribble et al., 2013). This anaerobe is an important component of the ‘red complex’, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium involved in periodontitis (Darveau, 2010). Moreover, P. gingivalis is now designated as a ‘keystone’ species, due to its ability to manipulate the host immune system, so eliciting a major effect on the composition of the oral microbial community and pathology of periodontitis (Hajishengallis, 2011; Darveau et al., 2012; Hajishengallis & Lamont, 2012). As an obligate anaerobe, P. gingivalis is unable to multiply in the presence of oxygen. However, it exhibits a high degree of aerotolerance, which enables the organism to survive within the periodontal pocket (Lamont & Jenkinson, 1998). A number of factors contribute to the pathogenesis of P. gingivalis, including the gingipains (Imamura, 2003; Potempa et al., 2003), cell wall lipopolysaccharides (Holt et al., 1999), sialidases and sialoglycoproteases (Aruni et al., 2011b) and the vim (virulence modulating) genes (Abaibou et al., 2001; Vanterpool et al., 2005a,b, 2006a,b, 2010; Osbourne et al., 2010). However, the ability to survive oxidative stress is important to its virulence, because the cells must be able to withstand the oxidative host defenses and persist in the relatively oxygenated tissues of the oral cavity.

There is a differential response of P. gingivalis to varying concentrations and durations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (McKenzie et al., 2012). We have previously shown that at a shorter exposure to H2O2-induced oxidative stress, the largest number of annotated genes to be expressed includes those involved in DNA replication, recombination and repair (Henry et al., 2012; McKenzie et al., 2012). After a longer exposure, several genes involved in protein folding/repair were induced whereas those involved in translation were reduced (McKenzie et al., 2012). Although the specific regulators are not completely understood, the system(s) associated with the response appear to have H2O2-induced characteristics (Henry et al., 2013). This implies that this bacterium can specifically adapt to the changing nature of the environment, typical of the periodontal pocket during the course of disease. Multiple mechanisms, with possible built-in redundancies, are known to work in synergy to protect and defend P. gingivalis against oxidative stress-induced damage (reviewed in Henry et al., 2013). For example, antioxidant enzymes such as AhpC may become upregulated to counteract the increase in oxidative stress. The hemin layer can form 8-oxo dimers in the presence of reactive oxygen species and can give rise to the catalytic degradation of H2O2 (Henry et al., 2012). Questions are raised on the relative significance of the multiple protective mechanisms and what the impact failure of one would have on the others.

The presence of the vim genes on the same transcriptional unit could be considered an important strategy for P. gingivalis to coordinate its oxidative stress resistance and other virulence properties (Aruni et al., 2011a). Inactivation of the vimA gene in P. gingivalis generated a non-black-pigmented isogenic mutant that showed increased sensitivity to H2O2 and increased repair activity of the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine lesion in its genome (Henry et al., 2008). The increased sensitivity of P. gingivalis vimA mutant FLL92 compared with the wild-type could be attributed to the lack of heme layer in the mutant (McKenzie et al., 2012). It is our hypothesis that in P. gingivalis, multiple coordinately regulated mechanisms involving vimA are vital for protection against oxidative stress and contribute significantly to the pathogenicity of the organism because this gene is essential in virulence modulation due to its network of functions. To elucidate the role of VimA in oxidative stress resistance, we have used a global approach to assess the transcriptional profile of a vimA isogenic mutant of P. gingivalis, exposed to an oxidatively stressed environment typical to that of the periodontal pocket (Leke et al., 1999; McKenzie et al., 2012), to study the unique metabolome variations affecting survival and virulence.

METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Porphyromonas gingivalis strains were cultured at 37°C in brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with yeast extract (5 mg ml−1), hemin (5 μg ml−1) (Sigma, St Louis, MO), menadione (0.5 μg ml−1) and DL-cysteine (1 mg ml−1) (Sigma) where indicated, under anaerobic conditions (10% H2, 10% CO2, 80% N2) in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Manufacturing, Ann Arbor, MI). For solid media, BHI broth was supplemented with 20 g l−1 agar and/or 5% sheep’s blood (Hemostat Laboratories, Dixon, CA).

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assays

Overnight cultures of P. gingivalis, grown in BHI broth without cysteine, were used to inoculate 50 ml pre-warmed BHI broth without cysteine to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. When the OD600 of cultures doubled (0.2), each culture was split in two and one half was treated with 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 or 1 mM final concentration H2O2 (Sigma). Final H2O2 concentrations were obtained by diluting a 3% weight/volume solution (0.88 mM) to the appropriate molarity in BHI. The other half of each culture was left untreated to serve as controls. All cultures were further incubated for 24 h and OD600 were measurements taken at specific intervals to assess cell growth. At each measured interval, 10−6 dilutions were made and 20 μl was spread on BHI agar plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep’s blood (Hemostat Laboratories). At least three independent experiments were conducted for statistical analysis.

RNA isolation and preparation for microarray analysis and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 cells grown to OD600 ~0.6 (mid-log) were treated with a final concentration of 0.1, 0.25 or 0.5 mM final concentration of hydrogen peroxide in BHI broth for 15 min or treated with 0.25 mM of H2O2 for 10 or 15 min. Untreated cells were also included as controls for each experiment. After incubation, cells were immediately centrifuged at room temperature at 8000 g for 5 min and the total RNA was extracted from the pellet using the Ribopure™ RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Residual genomic DNA was removed from RNA samples with DNA-free™ kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The integrity of the RNA samples was assessed spectrophotometrically by 260/280 ratios and visually for intact 16S and 23S rRNA bands by electrophoresis in an RNA formaldehyde gel (Sambrook & Russell, 2001).

Microarray slides

Whole-genome P. gingivalis W83 microarray slides were provided by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). Each slide consists of 1907 70-mer oligonucleotides designed based on the 2083 open reading frames predicted from TIGR’s annotation of the W83 strain. Each 70-mer oligonucleotide was printed as four replicates on the surface of the microarray slide.

Probe preparation, hybridization and data acquisition/analysis

Preparation and labeling of probes was carried out according the manufacturer’s protocol (http://pfgrc.tigr.org/protocols/M009.pdf) with slight modifications (McKenzie et al., 2012). Genes from all data sets were then classified into functional groups according to their annotation in the Comprehensive Microbial Database at TIGR (http://www.tigr.org).

Statistical analysis

All pairwise comparisons of three to five replicates were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The background signal was eliminated using the GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using Lowess normalization and the differentially expressed genes were identified using ANOVA test. Genes that were upregulated or downregulated were identified using the Fold Change tool of GeneSpring GX software. For 15-min exposure samples, statistical analysis was derived from the LIMMA package. The net signal for each spot was calculated by subtraction of the local background from the value of each spot. The average fold change for each gene was determined based on normalized values. For both sets of experiments, all gene data with a P-value < 0.05 and fold change of >2.0 were considered significant.

Validation of microarray results by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using the One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA) were designed to amplify randomly selected genes that were either up-regulated or downregulated from the 10-or 15-min hydrogen peroxide treatments as determined by microarray analysis (McKenzie et al., 2012).

Fumarate assay

A fumarate assay was performed using the Fumarate assay kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA). Briefly the P. gingivalis FLL92 strain was grown to log phase (OD 0.8). The cells were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min. The pelleted cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and then lysed using a French press at 20,000 psi. The lysate was cleared of unlysed cells by centrifugation (5000 g, 10 min, 4°C). The supernatant containing cytosolic fraction was used as the test sample. Then 50 μl of the prepared sample was added to a 96-well plate in triplicate, followed by the addition of 100 μl of the reaction mixture (90 μl fumarate assay buffer, 8 μl fumarate developer and 2 μl fumarate enzyme mix) to each well. A fumarate standard curve was generated using a series of concentrations (0–25 nmol per well) of the fumarate standard provided. The content was mixed well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min before measuring the absorbance at 450 nm in a microplate reader. The concentration of fumarate was calculated using the formula C = Sa/Sv nmol μl−1 (where Sa is the fumarate amount of the sample in nmol from the standard curve, Sv is the sample volume (ml) added into the wells).

Formaldehyde assay

A formaldehyde assay was carried out using a DetectX – Formaldehyde fluorescent detection kit (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI). The cells were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min. The pelleted cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and the cells were lysed using a French press at 20,000 psi. The lysate was cleared of unlysed cells by centrifugation (5000 g, 10 min, 4°C). The supernatant containing the cytosolic fraction was used as a test sample. Fifty microliters of the prepared samples was added to a 96-well plate and 25 μl of DetectX – Formaldehyde reagent was added to each well. The reagents were mixed by gently tapping the plate and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 510 nm excitation/450 nm emission in a Quantitek 800 spectrophotometer (Iotek Flx 800, Winooski, VT, USA). A standard curve was generated using a series of concentrations of the formaldehyde standard (3.125–200 μM) with water as the sample blank. The sample concentration was calculated from the standard curve using the KC4 software in the spectrophotometer.

In silico analysis

In silico analysis of microarray data and data interpretation were carried out using the ArrayStar software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI), version 3. Metabolomic analysis of the microarray data was performed using the KEGG pathway modules and pathway mapping modes (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). The metabolic pathway of P. gingivalis was reconstructed based on the published genome annotation of the organism (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The relevant reactions were added based on the gene–protein reaction assignment following compilation of the annotated metabolic genes (Feist et al., 2009) based on the information from the online databases such as Biosilico (Hou et al., 2004), BRENDA (Chang et al., 2009), ExPASy Enzyme (Bairoch, 2000) and KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2010). The process of model refinement was performed through data mining, facilitated by use of the PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

RESULTS

Transcriptome response of P. gingivalis to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide

The P. gingivalis vimA gene has been shown earlier to be multifunctional and is involved in oxidative stress resistance (Vanterpool et al., 2005a, 2006; Osbourne et al., 2010, 2012; Aruni et al., 2011a, 2013). The adaptability of the P. gingivalis vimA-defective mutant (FLL92) to H2O2-induced oxidative stress is enhanced compared with the wild-type strain (W83) (McKenzie et al., 2012). Further, its non-black-pigmented phenotype may raise questions about alternative mechanisms for survival under oxidative stress. Because the response of P. gingivalis to oxidative stress can be modulated by varying levels and duration of hydrogen peroxide-induced stress, a whole-transcriptome profiling was carried out using DNA microarray analysis to investigate the effects of different concentrations of H2O2 on the P. gingivalis FLL92 isogenic mutant. Hydrogen peroxide concentrations of 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM were shown to be sub-inhibitory, inhibitory and lethal, respectively (Johnson et al., 2004, 2011; McKenzie et al., 2012). The genes that were differentially expressed were categorized based on their functional distribution according to the Oral Pathogen Sequence Database annotation (www.oral-gen.org). In P. gingivalis FLL92 the majority of the genes were observed to be upregulated at a concentration of 0.25 mM H2O2 (Table 1). The genes commonly modulated in P. gingivalis FLL92 under varying treatment conditions are shown in Table 2. Furthermore, more genes were up-regulated in FLL92 compared with the wild-type (McKenzie et al., 2012). This gene expression pattern was similar to that at an exposure to 0.1 mM H2O2. At 0.5 mM H2O2, however, 12 genes were upregulated in the wild-type compared with nine genes in FLL92. In comparison to the wild-type, fewer genes were downregulated in the FLL92 mutant.

Table 1.

Summary of Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 genes affected by treatment with different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide

| 0.1 mM | 0.25 mM | 0.5 mM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | 52 | 63 | 9 |

| Downregulated | 1 | 6 | 5 |

Table 2.

Genes commonly modulated in Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 under different treatment conditions

| P. gingivalis FLL92 genes upregulated at 0.1 and 0.25 mM H2O2 | |

| PG1729 | Thiol peroxidase1 |

| PG1545 | Superoxide dismutase, Fe-Mn1 |

| PG0010 | ATP-dependent Clp protease, ATP-binding subunit ClpC1 |

| PG0686 | Conserved hypothetical protein1 |

| PG1208 | DnaK protein1 |

| PG1642 | Cation-transporting ATPase, EI-E2 family, authentic frameshift1 |

| PG1286 | Ferritin1 |

| PG0045 | Heat-shock protein HtpG1 |

| PG0521 | Chaperonin, 10 kDa1 |

| PG0520 | Chaperonin, 60 kDa1 |

| PG1775 | GrpE protein |

| PG0045 | Heat-shock protein HtpG1 |

| P. gingivalis FLL92 genes upregulated at 0.1 and 0.5 mM H2O2 | |

| PG0090 | Dps family protein |

| P. gingivalis FLL92 genes downregulated at 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM H2O2 | |

| PG0627 | RNA-binding protein |

These genes also modulated in P. gingivalis W83 under the same conditions (McKenzie et al., 2012).

While evaluating whether similar genes were expressed at all the different concentrations in both the wild-type strain and P. gingivalis FLL92, there were only eight genes commonly expressed in P. gingivalis W83 and P. gingivalis FLL92 at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.25 mM H2O2. No gene expression was impacted in the same way in both strains under all three H2O2 conditions.

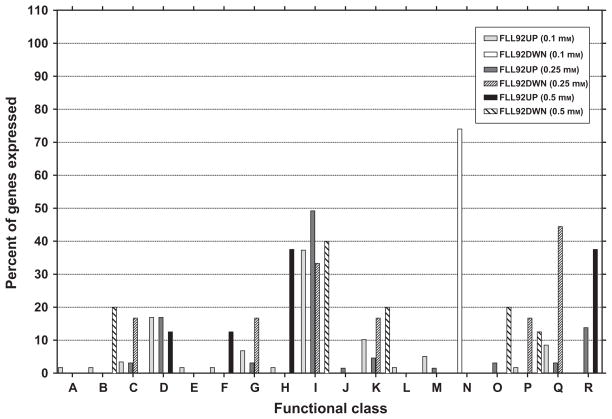

The repressed genes in P. gingivalis FLL92 were involved in cell envelope, energy metabolism, hypothetical/unknown/unassigned/uncategorized functions, protein fate and translation. In P. gingivalis FLL92 only, DNA metabolism, fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism genes were induced while protein fate and transcription genes were downregulated (Fig. 1). A comparison between upregulated genes of P. gingivalis W83 and FLL92 exposed to 0.25 mM H2O2 is given in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Functional distribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 genes after 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment. DNase-treated total RNA extracted from P. gingivalis FLL92 after 0.1, 0.25 or 0.5 mM H2O2 treatment was subjected to DNA microarray analysis. Functional gene classes were assigned according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory (www.oralgen.lanl.gov) as follows: (A) amino acid biosynthesis, (B) biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups and carriers, (C) cell envelope, (D) cellular processes, (E) central intermediary metabolism, (F) DNA metabolism, (G) energy metabolism, (H) fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism, (I) hypothetical/unassigned/uncategorized/unknown functions, (J) mobile and extrachromosomal element functions, (K) protein fate, (L) purines, pyrimidines, nucleosides and nucleotides, (M) regulatory functions, (N) replication, (O) transcription, (P) translation, (Q) transport and binding, (R) transposon functions.

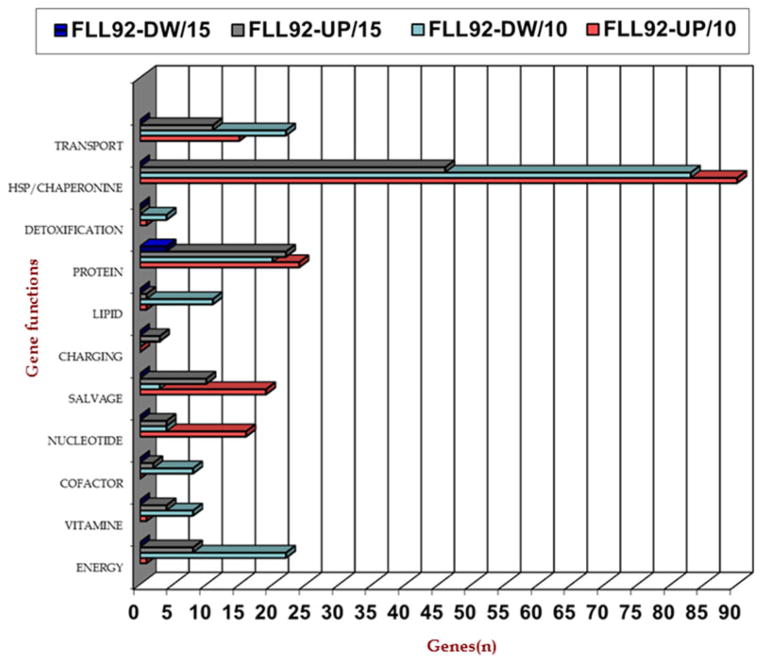

Figure 2.

Upregulated genes in Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 exposed to 0.25 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). DNase-treated total RNA extracted from P. gingivalis vimA mutant FLL92 after 0.25 mM H2O2 treatment was subjected to DNA microarray analysis showing functional classes of genes modulated during 10 and 15 min of exposure to H2O2.

Transcriptome response of P. gingivalis FLL92 to prolonged oxidative stress

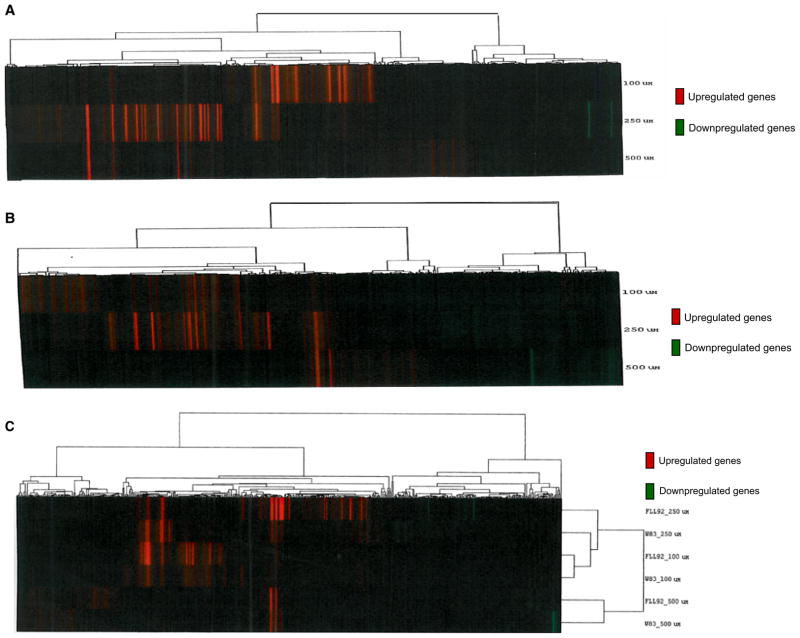

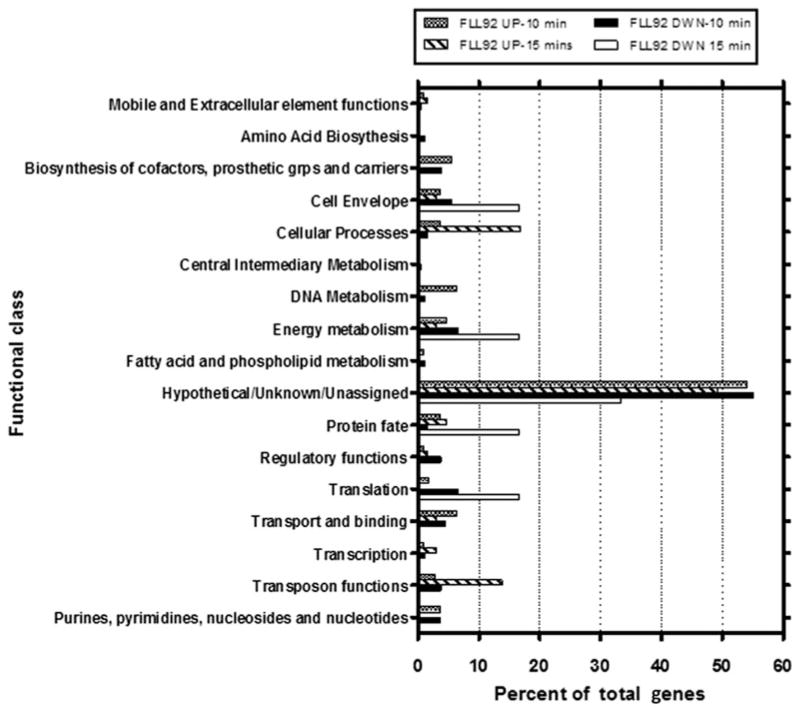

DNA microarrays were used to analyse gene expression profiles of cells grown in the presence of H2O2 for two different durations of exposure, to identify the pattern and recurrence of genes involved in combating oxidative stress in the P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant. A summary of the P. gingivalis FLL92 genes affected by treatment with different concentrations of H2O2 is given in Tables 2 and 4. A total of 11 genes were up-regulated at 0.1 and 0.25 mM hydrogen peroxide. The DPS family protein encoding gene PG0090 was the only gene commonly upregulated at 0.1 and 0.5 mM H2O2, whereas the RNA binding protein gene PG0627 was generally downregulated at 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM H2O2. Table 3 presents the genes that were upregulated after 10- or 15-min exposures to H2O2. The results represent three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Variations in gene expression were observed in some gene clusters, when comparing the microarray cluster heat map to the global transcriptome data of P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant and the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 was associated with more upregulated genes when exposed to 0.25 mM H2O2 (Fig. 3A, B), compared with the wild-type strain. It was noted that more genes were upregulated in P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant than in the wild-type, with a 10-min exposure at any of the three H2O2 concentrations tested (Fig. 3C). The functional distributions of the modulated genes during 10- and 15-min treatments are given in Fig. 4.

Table 4.

Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 upregulated genes during 15-min exposure to 0.25 mM hydrogen peroxide

| Gene ID | Fold | Common name of the gene |

|---|---|---|

| PG0010 | 3.525847 | ATP dependant Clp Protease |

| PG0045 | 3.693708 | Heat-shock protein, HtpG |

| PG0051 | 11.87022 | ISPg1 transposase degenerate |

| PG0182 | 6.66159 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0194 | 10.28924 | ISPg1 transposase truncation |

| PG0245 | 2.929 | Universal stress protein family |

| PG0246 | 3.690019 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0293 | 4.600862 | Secretion activator protein |

| PG0319 | 2.04 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0339 | 3.299585 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0340 | 3.188841 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0409 | 3.301019 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0410 | 2.70 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0411 | 2.35 | Hemagglutinin putative |

| PG0418 | 2.13 | ATP dependant Clp Protease |

| PG0520 | 3.732671 | Chaperonin 60 kDa |

| PG0521 | 3.693925 | Chaperonin 11 kDa |

| PG0611 | 2.34 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0612 | 2.31 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0614 | 2.04 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0618 | 3.548024 | Alkyl preoxidase reductase |

| PG0619 | 3.00989 | Alkyl hydroperoxidase reductase F |

| PG0686 | 2.18 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0812 | 9.21 | ISPg1 transpoase truncate |

| PG0813 | 9.612998 | ISPg1 transposase truncate |

| PG0833 | 2.22 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0834 | 2.924 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0858 | 2.09 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0860 | 2.03 | Transcriptional regulator |

| PG0861 | 2.50 | Helicase family |

| PG0944 | 11.96845 | ISPg1 transposase degenerate |

| PG0988 | 4.857384 | ISPg1 transposase degenerate |

| PG0993 | 2.07 | Transposase ISPg2 related |

| PG0997 | 2.03 | Transcriptional regulator |

| PG0999 | 2.16 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1003 | 2.44 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG1030 | 2.30 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1055 | 3.923686 | Thiol protease |

| PG1085 | 3.189495 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1151 | 2.33 | Alcohol dehydrogenase iron containing |

| PG1171 | 2.14 | Oxidoreductase putative |

| PG1208 | 5.291382 | dnaK protein |

| PG1240 | 2.75 | Transcription regulator tetR |

| PG1286 | 3.566204 | Ferritin |

| PG1326 | 2.50 | Hemagglutinin putative |

| PG1372 | 2.04 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1491 | 5.03 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1492 | 5.335137 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1493 | 2.03 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1497 | 2.06 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1545 | 3.007593 | Superoxide dismutase Fe-Mn |

| PG1642 | 2.56 | Cation transporting ATPase E1-E2 family |

| PG1729 | 3.869879 | Thiol peroxidase |

| PG1775 | 3.373765 | grpE protein |

| PG1798 | 2.67 | Immunoreactive 46 kDa antigen |

| PG1820 | 2.11 | Cytochrome C nitrate reductase NfrA |

| PG1821 | 4.208868 | Cytochrome C nitrate reductase NfrH |

| PG1827 | 2.09 | RNA polymerase sigma −70 factor |

| PG1837 | 4.777919 | Hemagglutination protein HagA |

| PG1907 | 2.55 | ISPg1 transposase interruption |

| PG1908 | 2.65 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2020 | 2.06 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2031 | 3.098431 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2169 | 11.12423 | ISPg1 transposase degenerate |

| PG2212 | 4.041899 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2213 | 4.079182 | Nitrate reductase related protein |

Table 3.

Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL-92 upregulated genes during 10-min exposure to 0.25 mM hydrogen peroxide

| Gene ID | Fold | Common name of the gene |

|---|---|---|

| PG0131 | 2.925211 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0134 | 4.2127607 | Magnesium transporter |

| PG0176 | 2.524799 | Cell surface protein, interruption |

| PG0192 | 2.7022871 | Cationic outer membrane protein OmpH |

| PG0195 | 2.3024246 | Rubrerythrin |

| PG0199 | 2.5737364 | TatD family protein |

| PG0227 | 2.8909848 | DNA repair protein RadA |

| PG0248 | 2.2419755 | Translation initation factor SUI1, putative |

| PG0259 | 3.0020967 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0277 | 2.4539853 | ISPg2, transposase |

| PG0326 | 5.3249413 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0423 | 3.3248539 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0454 | 3.0034393 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0523 | 2.3294317 | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase |

| PG0543 | 2.2128535 | Transcriptional regulator, putative |

| PG0556 | 2.0984164 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0562 | 7.3588564 | Potassium uptake protein TrkA, putative |

| PG0583 | 6.9532863 | Cell division protein FtsA |

| PG0601 | 2.6175846 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0630 | 2.1782202 | Pyridoxal phosphate biosynthetic protein PdxJ |

| PG0651 | 2.7535497 | HDIG domain protein |

| PG0661 | 3.1014013 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0662 | 3.1029224 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0666 | 2.7256413 | mdsC protein, authentic frameshift |

| PG0677 | 6.2779748 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0678 | 2.8965723 | Pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, putative |

| PG0685 | 2.5050306 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| PG0704 | 2.519914 | Phosphoglycerate mutase family protein |

| PG0721 | 2.460936 | NLP/P60 family protein |

| PG0729 | 6.4661842 | D-alanine–D-alanine ligase |

| PG0732 | 2.5454633 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0751 | 3.4026118 | porT protein |

| PG0757 | 2.1590543 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0773 | 2.5259254 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0791 | 2.2543833 | Adenylate kinase |

| PG0792 | 2.0714259 | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| PG0797 | 2.0709278 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0798 | 2.7581866 | ISPg3, transposase |

| PG0811 | 2.4192631 | Holliday junction DNA helicase RuvA |

| PG0831 | 2.4438001 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0834 | 2.5704243 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0840 | 5.3756298 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0848 | 4.0429962 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0855 | 2.9758149 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0866 | 2.2800069 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0868 | 2.4619528 | Mobilization protein |

| PG0870 | 2.5588419 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0921 | 2.1439161 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0962 | 3.4397415 | Prolyl-tRNA synthetase |

| PG1017 | 3.5399219 | Pyruvate phosphate dikinase |

| PG1022 | 2.0330621 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1030 | 4.9524365 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1036 | 2.0594624 | Excinuclease ABC, A subunit |

| PG1054 | 3.277287 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1060 | 5.1684345 | Carboxyl-terminal protease |

| PG1091 | 2.8524055 | DHH subfamily 1 protein |

| PG1124 | 2.1709207 | DUF80 domain protein |

| PG1145 | 2.0970461 | Long-chain-fatty-acid–CoA ligase, putative |

| PG1201 | 12.248168 | Conserved hypothetical protein, degenerate |

| PG1202 | 2.0986403 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1211 | 2.0124948 | Hexapeptide transferase family protein |

| PG1233 | 5.4165149 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1235 | 2.0797322 | Epimerase/reductase, putative |

| PG1236 | 5.5059223 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1294 | 2.0615625 | Ferrous iron transport protein B |

| PG1300 | 2.082116 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG1305 | 3.2483373 | Glycine cleavage system P protein |

| PG1313 | 2.2327982 | Conserved domain protein |

| PG1345 | 5.05422 | Glycosyl transferase, group 1 family protein |

| PG1352 | 2.3185153 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1380 | 2.1078958 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| PG1383 | 2.0192496 | Amino acid exporter, putative |

| PG1412 | 2.1398607 | ISPg2, transposase, truncation |

| PG1495 | 8.1634196 | DNA topoisomerase III |

| PG1500 | 2.3038659 | Conserved domain protein |

| PG1507 | 2.191139 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1515 | 2.1624568 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-related protein |

| PG1538 | 2.7634023 | Undecaprenol kinase, putative |

| PG1544 | 4.2326759 | yaaA protein |

| PG1571 | 2.3952514 | Metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily protein |

| PG1577 | 4.8937044 | Nicotinate-nucleotide pyrophosphorylase |

| PG1583 | 5.1827993 | batB protein |

| PG1648 | 2.2070572 | RelA/SpoT family protein |

| PG1714 | 4.7256662 | Pyridoxamine-phosphate oxidase |

| PG1762 | 2.9499151 | Protein-export membrane protein SecD/protein-export membrane protein SecF |

| PG1780 | 2.0715887 | 8-amino-7-oxononanoate synthase |

| PG1805 | 2.3587395 | v-type ATPase, subunit D |

| PG1831 | 2.7054174 | ATP-dependent DNA helicase RecQ |

| PG1893 | 5.5281588 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG1899 | 2.3780095 | TonB-dependent receptor, putative |

| PG2022 | 2.5346746 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2024 | 3.4983313 | Arginine-specific protease ArgI polyprotein |

| PG2032 | 2.0018153 | Primosomal protein n′ |

| PG2037 | 4.5315641 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2043 | 3.7208481 | Conserved hypothetical protein TIGR00486 |

| PG2071 | 5.6931259 | Conserved domain protein |

| PG2083 | 5.2882661 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2086 | 2.1725989 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2096 | 6.5503014 | Conserved domain protein |

| PG2099 | 4.4935507 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase, DEAD/DEAH box family |

| PG2110 | 2.7396287 | Thiamine biosynthesis protein ThiC |

| PG2147 | 2.18657 | Xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| PG2164 | 2.1515218 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, FKBP-type |

| PG2166 | 2.1256978 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2179 | 2.1292322 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, Na translocating, D subunit |

| PG2203 | 2.2710931 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2210 | 13.572298 | Excinuclease ABC, A subunit |

| PG2226 | 2.1923208 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG2227 | 2.2598202 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0131 | 2.925211 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0134 | 4.2127607 | Magnesium transporter |

| PG0176 | 2.524799 | Cell surface protein, interruption |

| PG0192 | 2.7022871 | Cationic outer membrane protein OmpH |

| PG0195 | 2.3024246 | Rubrerythrin |

| PG0199 | 2.5737364 | TatD family protein |

| PG0227 | 2.8909848 | DNA repair protein RadA |

| PG0248 | 2.2419755 | Translation initation factor SUI1, putative |

| PG0259 | 3.0020967 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0277 | 2.4539853 | ISPg2, transposase |

| PG0326 | 5.3249413 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0423 | 3.3248539 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0454 | 3.0034393 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0523 | 2.3294317 | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase |

| PG0543 | 2.2128535 | Transcriptional regulator, putative |

| PG0556 | 2.0984164 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0562 | 7.3588564 | Potassium uptake protein TrkA, putative |

| PG0583 | 6.9532863 | Cell division protein FtsA |

| PG0601 | 2.6175846 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0630 | 2.1782202 | Pyridoxal phosphate biosynthetic protein PdxJ |

| PG0651 | 2.7535497 | HDIG domain protein |

| PG0661 | 3.1014013 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0662 | 3.1029224 | Hypothetical protein |

| PG0666 | 2.7256413 | mdsC protein, authentic frameshift |

| PG0677 | 6.2779748 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PG0678 | 2.8965723 | Pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, putative |

| PG0685 | 2.5050306 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| PG0704 | 2.519914 | Phosphoglycerate mutase family protein |

Figure 3.

Microarray-based cluster heat map of Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 mutant showing modulated genes compared with the wild-type during oxidative stress. Hierarchical clustering generated heat map of gene expression. Dendrogram shows similar cluster organization between the upregulated and downregulated genes. The columns represent the genes and the rows represent various treatments. (A) P. gingivalis W 83, wild-type, (B) P. gingivalis vimA mutant FLL92, (C) comparison of modulated genes in P. gingivalis W83 and FLL92 during 10-min exposure to hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 4.

Functional distribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 genes affected by 10- and 15-min treatment with 0.25 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The P. gingivalis FLL92 genes modulated by H2O2 treatment were determined and functionally categorized according to Los Alamos National Laboratory (www.oralgen.lanl.gov). Each functional group is represented as a percentage of total genes expressed under the conditions described.

Analysis of the microarray data revealed that about 5.7% and 3.45% of the P. gingivalis genome displayed altered expression in response to H2O2 exposure at 10 and 15 min, respectively (P ≤ 0.05). The P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant, in response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress, showed upregulation of several genes, including some known to be involved in oxidative stress resistance. The duration of oxidative stress was shown to differentially modulate transcription. After 10-min exposure of P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant to oxidative stress, 94 (87%) genes were upregulated twofold (Table 3). After a 15-min exposure to oxidative stress, 55 (83.3%) out of 66 upregulated genes showed a twofold increase in their expression levels (Table 4). The hypothetical/unknown/unassigned functional class of genes (55%), genes involved in DNA metabolism (8%) and Transport and binding protein coding genes (8%), were highly upregulated during oxidative stress after 10-min exposure. Similarly, there was an increased upregulation of hypothetical/unknown/unassigned functional class of genes, followed by genes involved in cellular processes and transposon functions, after 15 min of exposure to oxidative stress. It is interesting to note that three genes (PG1545 superoxide dismutase; PG0045 heat-shock protein, htpG; PG0409 hypothetical protein) were found to be upregulated in both P. gingivalis W83 and P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant during oxidative stress.

Metabolome variations in P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant during oxidative stress

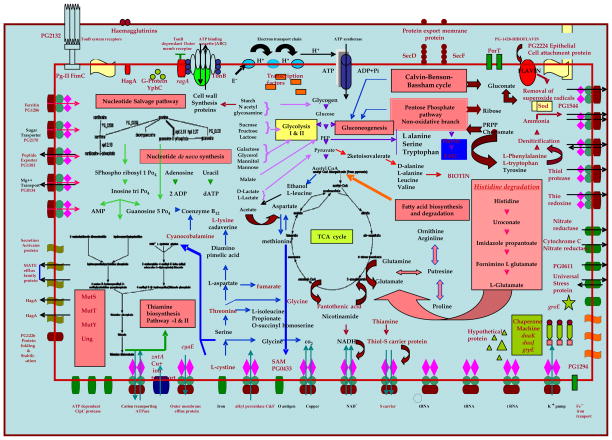

Oxidative stress is known to affect the overall bacterial physiology and regulate cellular processes in response to stress (Gaupp et al., 2012). The microarray data were further used to analyse the metabolome of P. gingivalis during oxidative stress and the various biochemical pathways and their modulations (Fig. 5). The major upregulated biochemical pathways and their intermediary biochemical metabolites are shown in red. A comparison of regulated pathways in P. gingivalis FLL92, after a 10- and 15-min exposure to oxidative stress, is given in Table 5. It was noted that basic and important cellular metabolic processes like glycosylation, protein catabolism, fatty acid elongation, detoxification processes, cell signaling and protein transport pathways were upregulated after the 10-min interval. After a 15-min exposure to such oxidative stress, upregulation of gene expression was observed in the chaperone machinery, stress related proteins, detoxification processes and gingipains. It is important to note that there was a downregulation of the arginine-specific cystine proteases, rgpB, during the 10-min interval of oxidative stress. The metabolome data suggest that fumarate is upregulated during oxidative stress and could be used as an intermediary metabolite in the energy cycle. In contrast, with 15 min of oxidative stress, there was upregulation in protein transport systems. Table 6 gives a comparison of upregulated proteins involved in transport systems between 10 and 15 min of oxidative stress. In comparison to the wild-type, the P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant had more upregulated genes involved in protein transport (Table 7). It was ascertained by the transcriptome data that protein secretion systems play a vital role in P. gingivalis FLL92 during oxidative stress, when genes involved in the protein transport pathway [Resistance modulation division (RND) and Multidrug and toxic component extrusion (MATE)], protein transport [ATP binding cassette (ABC), Transmembrane protein (TMP)], protein processing and folding [heat shock protein (HSP) and Chaperonins] and finally the genes coding for signal peptides were all found to be upregulated. Hence a whole series of pathways involving protein secretion and transport was upregulated in FLL92 during oxidative stress.

Figure 5.

Metabolome variations in Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 during oxidative stress. Metabolomics analysis was done using the KEGG pathway modules based on the published annotations in the NCBI database.

Table 5.

Comparison of modulated pathways in Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92 during 10- and 15-min exposure to oxidative stress

| Upregulated 10 min | Glycosylation |

| Protein catabolism | |

| Fatty acid elongation | |

| Vitamin synthesis: alanine, nicotinic acid, thiamine, cyanocobalamine, biotin, threonine, nicotinamide | |

| Glycine cleavage system | |

| Detoxification: through superoxide reductase, oxidoreductase, ruberythrin hemoxidation | |

| G-protein-signaling system | |

| Redox-sensitive transcription activation | |

| Protein transport through ion channel | |

| Fimbrial expression | |

| Upregulated 15 min | Chaperone machinery |

| Stress protein synthesis | |

| Transposases | |

| Detoxification: nitrate reductase cytochrome c nitrate reductase, superoxide desmutase (sod) alkyl hydroperoxidase reductases C and F thiol peroxidase | |

| Downregulated 10 min | Outer membrane synthesis and glycosylation |

| Stationary phase survival protein synthesis | |

| Lipid-A and lipoprotein synthesis | |

| Thioredoxin reductase | |

| Gingipain synthesis (RgpB) | |

| Folate synthesis | |

| Protoporphyrin metabolism | |

| Downregulated 15 min | Protein folding |

| HU related DNA binding expression of genes | |

| RNA binding protein related functions | |

| O antigen synthesis | |

| Chromosome replication initiation |

Table 6.

Upregulated proteins involved in protein transport during oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92

| Upregulated 10 min | |

| PG0868 | Mobilization protein |

| PG1060 | C-terminal protease |

| PG1868 | C-terminal protein |

| PG1762 | Protein export membrane system SecD, SecF |

| PG0631 | Biopolymer transport protein (ExbD) |

| PG0075 | PorT |

| PG0192 | Cation outer membrane protein |

| PG0685 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein |

| PG1899 | TonB receptor binding protein |

| PG1544 | YaaA protein –H2O2 scavenging |

| PG1091 | DHH super family protein |

| PG0651 | HDIG domain protein |

| PG0666 | MdsC protein |

| PG0199 | TatD family protein |

| PG0721 | NLP/P60 family protein |

| PG1124 | DUF 80 domain protein (exosortase like) |

| PG1211 | Hexa peptide transferase |

| PG1383 | Amino acid exporter |

| PG0562 | Potassium uptake/transport protein-Trk |

| PG0134 | Magnesium transporter protein |

| PG2164 | Peptidyl polycis-trans isomerase |

| PG0962 | Prolyl trna synthetase |

| PG1583 | Auto transporter BatB |

| Upregulated 15 min | |

| PG0293 | Secretion activator protein |

| PG0010, PG0418 | Ion channel proteins – (clpC and clpP) Transport and binding proteins |

| PG-1642 | Cation transporting ATPase – (ZntA) |

Table 7.

Comparison of transport proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 and FLL92

| P. gingivalis W83 | Upregulated 10 min | PG0562 | Potassium uptake protein |

| PG0134 | Magnesium transporter | ||

| PG1899 | TonB receptor | ||

| PG0959 | ATP binding protein | ||

| PG0632 | Biopolymer transport protein | ||

| PG0631 | Proton channel protein | ||

| PG1762 | Protein export membrane protein SecD and SecF | ||

| PG0151 | Signal recognition particle docking protein | ||

| PG1020 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| Upregulated 10 min | PG1642 | Cation transporting ATase | |

| PG0010 | ATP dependent protease clpP | ||

| PG1868 | Membrane protein | ||

| P. gingivalis FLL92 | Upregulated 10 min | PG0868 | Mobilization protein |

| PG1060 | C-terminal protease | ||

| PG1868 | C-terminal protein | ||

| PG1762 | Protein export membrane system (secD, SecF) | ||

| PG0632 | Biopolymer transport protein | ||

| PG0751 | PorT | ||

| PG0192 | Cation outer membrane protein | ||

| PG0685 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein | ||

| PG1760, PG1034 | ABC transporter | ||

| PG1899 | TonB receptor binding protein | ||

| PG1544 | YaaH protein H2O2 scavenging | ||

| PG1091 | DHH Super family protein | ||

| PG0651 | HDIG domain protein | ||

| PG0666 | MdsC protein | ||

| PG0199 | TatD family protein | ||

| PG0721 | NLP/P60 family protein | ||

| PG1211 | Hexapeptide transferase | ||

| PG1383 | Amino acid exporter | ||

| PG0562 | Potassium uptake transport protein | ||

| PG0134 | Magnesium transporter protein | ||

| PG2164 | Peptidyl prolyl cic-trans isomerase | ||

| PG1583 | Auto transporter BatB | ||

| Upregulated 15 min | PG0868 | Mobilization protein | |

| PG1060 | C-terminal protease | ||

| PG1868 | C-terminal protein | ||

| PG1762 | Protein export membrane system (SecD, SecF) |

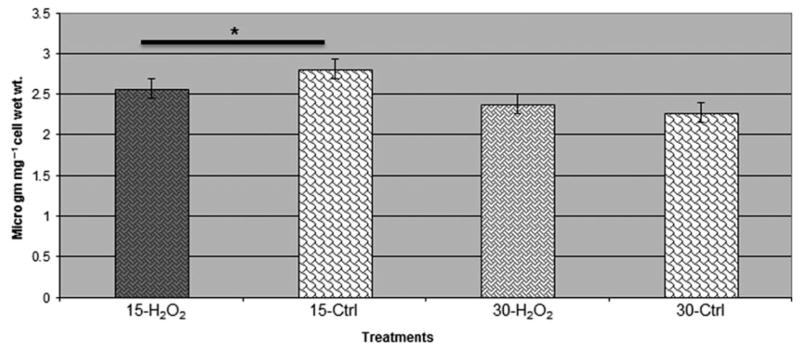

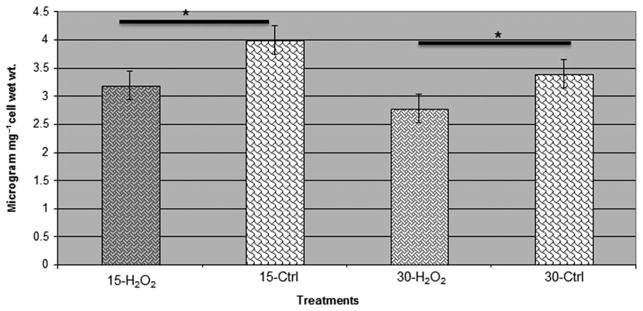

Confirmation of metabolome variation by estimation of intermediary metabolites

The metabolome variations during oxidative stress in the P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant strain were confirmed by assessing the intermediary metabolites that were modulated during the stress condition. We observed a reduction in the production of fumarate in the P. gingivalis FLL92 (Fig. 6), which could indicate increased assimilation of this metabolite for the production of energy during oxidative stress. Therefore, this could be a possible mechanism to use the products of protein catabolism for energy production during stress conditions. Also, there were reduced levels of formaldehyde in the P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant during oxidative stress, an important component involved in maintaining an anaerobic environment (Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

Estimation of fumarate in Porphyromonas gingivalis vimA mutant during oxidative stress. Fumarate was estimated in P. gingivalis vimA mutant during oxidative stress using a Fumarate assay kit (Biovision). The production of fumarate was less during oxidative stress among the P. gingivalis mutants compared with the untreated controls during 15- and 30-min exposure to H2O2 (*P < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Estimation of formaldehyde in Porphyromonas gingivalis vimA mutant during oxidative stress. Formaldehyde was estimated in P. gingivalis vimA mutant during oxidative stress using DetectX Formaldehyde fluorescent detection kit (Arbor Assays). The production of formaldehyde was less during oxidative stress among the P. gingivalis mutants compared with the untreated controls during 15-min and 30-min exposure to hydrogen peroxide. *P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The adaptability and survival of P. gingivalis in the oxidative microenvironment of the periodontal pocket are modulated by multiple inducible systems (Henry et al., 2012). While several genes were shown to influence the synthesis of defensive proteins in response to oxidative stress, the vimA gene can play a significant role in this process (McKenzie et al., 2012). Because of the changing environmental conditions in addition to the cyclic nature of periodontal disease, we envision alteration in the expression of the different defense systems to meet specific demands. Furthermore, a defect in any one of the systems would suggest differential modulation in others to allow the organism to protect itself from the deleterious effects of oxidative stress. Under comparable conditions of oxidative stress, our study has shown a similar pattern of gene expression in the vimA-defective mutant compared with the wild-type strain as previously reported (McKenzie et al., 2012). The genes classified as hypothetical/unclassified/uncharacterized/unknown function were highly modulated in P. gingivalis FLL92, similar to P. gingivalis W83 (McKenzie et al., 2012). However, in contrast, two of the gene classifications, fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism and the transposon functions, were highly upmodulated in FLL92 compared with P. gingivalis W83 (McKenzie et al., 2012).

The increased sensitivity of FLL92 to H2O2 compared with the wild-type strain has revealed additional strategies that P. gingivalis may use to combat oxidative stress. A multilayered protection strategy against oxidative stress was noted in P. gingivalis FLL92. We observed the upregulation of the thioredoxin system genes [thioredoxin (PG0275) and pyruvate ferredoxin (PG0548)] and genes encoding some of the major detoxification proteins like superoxide dismutase, alkyl hydroperoxidases (AphC, AphF). In bacteria, thioredoxins, based on their low redox potential, are major dithiol reductants in the cytosol and also function as antioxidants (Koharyova & Kolarova, 2008). Additionally, they also have hydroxyl radical (HO–) scavenging properties (Arner & Holmgren, 2000). The gene expression profile suggested that there was a generalized increase of reduction reactions catalysed through major energy pathway enzymes, metalloproteins, metalloenzymes and non-heme proteins like ferritin, ruberythrin (PG0195), cytochrome (PG1820), porphyrin, glutathione peroxidase, nitrate reductase, glucose-6-phosphate and alcohol dehydrogenase (PG1151). Hence, it is likely that metabolic reactions that can favor or enhance the redox potential of the cell are vital under conditions of oxidative stress. The upregulation of feoB2 (PG1294) in P. gingivalis FLL92, encoding for a major manganese transporter, is consistent with a previous report that demonstrated its protective ability from oxidative stress generated by atmospheric oxygen and H2O2 in P. gingivalis (He et al., 2006). Although the mechanism in P. gingivalis is unclear, the protective role of manganese against oxidative stress has been shown to involve enzymatic and non-enzymatic means (Culotta & Daly, 2013). With the upregulation of the superoxide dismutase in P. gingivalis FLL92, it is likely that manganese, which is a required cofactor, is needed to make the manganese–superoxide dismutase more stable in the presence of H2O2 (He et al., 2006). It is noteworthy that the superoxide dismutase in P. gingivalis is mostly induced in the presence of air (Lewis et al., 2009), but may be functional under extreme H2O2-induced oxidative stress conditions as observed in P. gingivalis FLL92 as well as in the wild-type strain under prolonged oxidative stress (McKenzie et al., 2012). In addition to the superoxide dismutase gene (PG1545), two other genes in the same cluster PG1544 and PG1543 were also upregulated under oxidative stress. The roles of PG1544 (YaaA) and PG1543 (annotated as a hypothetical protein), are yet to be elucidated. Preliminary in silico analysis of PG1544 suggests that this protein may have sensor/activator-like properties. The transcriptional regulation of super-oxide dismutase (PG1545), during oxidative stress in P. gingivalis is complex and involves an OxyR-independent component (Ohara et al., 2006; Xie and Zheng, 2012). It is unclear what role PG1544 may play in this process. This remains to be further elucidated in the laboratory.

The metabolic process can probably be used to combat oxidative stress in P. gingivalis. Although the major metabolites are derived from central pathways, the availability of important cellular intermediates and their alternation is a mode of response regulation during oxidative stress. Oxidative stress alters enzymatic activity, resulting in changes of metabolite concentrations and the redox environment. These changes in the bacterial metabolic status create signals that alter the activity of redox responsive metabolite. Major anti-oxidant enzymes such as fumarase C, aconitase A, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and glutathione reductase were shown to play a similar regulatory role (Imlay, 2008). Pyruvate synthesis and glycine catabolism were found to be upregulated during oxidative stress in P. gingivalis FLL92 and these reactions could produce more endogenous CO2 for maintaining the environment. Pyruvate fermentation to acetate is enhanced (upregulation of PG1286) and this by-product could be used by the anaerobic cycle and Calvin cycle for energy production. Pyruvate can also be converted into hydroxypyruvate which can detoxify the peroxides (Lewis et al., 2009). There was also upregulation of fumarate, suggesting that it could act as an alternative source of energy from the other catabolic pathways. Additionally, there was a shift in the intermediary metabolites of energy cycle where P. gingivalis FLL92 derives energy through alternative pathways. Fumarate reduction brings about formation of CO2, formate, acetate and acetoin and a decreased formation of lactate. This was shown to be an important method of diversion from normal glucose fermentation (Deibel & Kvetkas, 1964). Based on our data, the anaerobic fermentation of glycerol was enhanced by fumarate, which suggested its involvement in the anaerobic tricarboxylic acid cycle. Our recent findings also showed that there is an aberrant tricarboxylic acid cycle in P. gingivalis that becomes active during oxidative stress conditions (unpublished data). Additionally in P. gingivalis FLL92, formaldehyde assimilation and folic acid synthesis, both involved in serine metabolism, were upregulated. Also, regulation of glycine metabolism, through the glyoxylate cycle, could not only contribute to maintain cellular CO2 levels, but also could act in alternative oxidative response.

During oxidative stress, there was increased homo-cysteine and methionine metabolism in P. gingivalis FLL92. Methionine acts as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of cysteine, carnitine, taurine, lecithin, phosphatidylcholine and other phospholipids. This could be a possible way of lipoxidative replenishment. An increase in biotin synthesis could facilitate transfer of cytosolic carbon dioxide during fatty acid synthesis and energy metabolism by way of carboxylation, decarboxylation and transcarboxylation reactions (Delli-Bovi et al., 2010). This provides further support for our previous findings that VimA is involved in fatty acid catabolism (Aruni et al., 2011a). Additionally, there is involvement of the anaerobic pentose phosphate pathway in upregulation of nicotinic acid (PG1577) and thiamine (PG0630). Upregulation of ribofiavin synthesis could possibly imply its regulatory role in the energy-mediated superoxide radical scavenging activity during oxidative stress (Deldar & Yakhchali, 2011).

Based on the microarray data, the vimA-defective mutant exhibited alternative pathways of combating oxidative stress. First, the data showed that there was an overall upregulation in the expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in reduction reaction mechanisms. Second, there was an upregulation of DNA repair pathways and detoxification pathways through increased metal ion binding and transport proteins. Third, due to the upregulation of a number of transposases during oxidative stress, it is tempting to speculate that a transposase-mediated detoxification buffering system could be involved in combating reactive oxygen species. Fourth, protein transportation could bring about four types of secretory systems, including vesicle formation, which could lead to the dissemination of virulent proteins such as proteases and hemagglutinins. Finally, we can speculate that a type III secretory system, or its variant, could be operating during oxidative stress in the P. gingivalis FLL92 mutant. Taken together, the data from this study have extended our working knowledge of the ability of P. gingivalis to combat oxidative stress under extreme conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Loma Linda University and Public Health Services Grants DE13664, DE019730, DE019730 04S1, DE022508, DE022724 from NIDCR (to H.M.F).

References

- Abaibou H, Chen Z, Olango GJ, Liu Y, Edwards J, Fletcher HM. Vima gene downstream of Reca is involved in virulence modulation in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Infect Immun. 2001;69:325–335. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.325-335.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner ES, Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruni AW, Lee J, Osbourne D, et al. Vima-dependent modulation of acetyl-coa levels and lipid a biosynthesis can alter virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2011a;80:550–564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06062-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruni W, Vanterpool E, Osbourne D, et al. Sialidase and sialoglycoproteases can modulate virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2011b;79:2779–2791. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruni AW, Robles A, Fletcher HM. Vima mediates multiple functions that control virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2013;28:167–180. doi: 10.1111/omi.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A. The enzyme database in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:304–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Scheer M, Grote A, Schomburg I, Schomburg D. Brenda, amenda and frenda the enzyme information system: new content and tools in 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D588–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culotta VC, Daly MJ. Manganese complexes: diverse metabolic routes to oxidative stress resistance in prokaryotes and yeast. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:933–944. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darveau RP. Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:481–490. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darveau RP, Hajishengallis G, Curtis MA. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J Dent Res. 2012;91:816–820. doi: 10.1177/0022034512453589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deibel RH, Kvetkas MJ. Fumarate reduction and its role in the diversion of glucose fermentation by Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:858–864. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.4.858-864.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deldar A, Yakhchali B. The influence of ribo-flavin and nicotinic acid on Shigella sonnei colony conversion. Iran J Microbiol. 2011;3:13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delli-Bovi TA, Spalding MD, Prigge ST. Overexpression of biotin synthase and biotin ligase is required for efficient generation of sulfur-35 labeled biotin in E. Coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feist AM, Herrgard MJ, Thiele I, Reed JL, Pals-son BO. Reconstruction of biochemical networks in microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:129–143. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaupp R, Ledala N, Somerville GA. Staphylococcal response to oxidative stress. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:33. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G. Immune evasion strategies of Porphyromonas Gingivalis. J Oral Biosci. 2011;53:233–240. doi: 10.2330/joralbiosci.53.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Liang S, Payne MA, et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal micro-biota and complement. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Miyazaki H, Anaya C, Yu F, Yeudall WA, Lewis JP. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis Feob2 in metal uptake and oxidative stress protection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4214–4223. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00014-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, Sandberg L, Zhang K, Fletcher HM. Dna repair of 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine lesions in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7985–7993. doi: 10.1128/JB.00919-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, McKenzie RM, Robles A, Fletcher HM. Oxidative stress resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:497–512. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, Aruni W, Sandberg L, Fletcher HM. Protective role of the Pg1036-Pg1037-Pg1038 operon in oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:E69645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt SC, Kesavalu L, Walker S, Genco CA. Virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:168–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou BK, Kim JS, Jun JH, et al. Biosilico: an integrated metabolic database system. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3270–3272. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Cunge Z. OxyR activation in Porphyromonas gingivalis in response to hemin-limited environment. Infect Immun. 2012;80(10):3471–3480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00680-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T. The role of gingipains in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2003;74:111–118. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NA, McKenzie R, Mclean L, Sowers LC, Fletcher HM. 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine is removed by a nucleotide excision repair-like mechanism in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7697–7703. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7697-7703.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NA, McKenzie RM, Fletcher HM. The bcp gene in the bcp-recA-vimA-vimE-vimF operon is important in oxidative stress resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2011;26:62–77. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. Kegg for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koharyova M, Kolarova M. Oxidative stress and thioredoxin system. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2008;27:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1244–1263. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1244-1263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leke N, Grenier D, Goldner M, Mayrand D. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on growth and selected properties of Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP, Iyer D, Anaya-Bergman C. Adaptation of Porphyromonas gingivalis to microaerophilic conditions involves increased consumption of formate and reduced utilization of lactate. Microbiology. 2009;155:3758–3774. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027953-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie RM, Johnson NN, Aruni W, Dou Y, Masinde G, Fletcher HM. Differential response of Porphyromonas gingivalis to varying levels and duration of hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. Microbiology. 2012;158:2465–2479. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.056416-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara N, Kikuchi Y, Shoji M, Naito M, Nakayama K. Superoxide dismutase-encoding gene of the obligate anaerobe Porphyromonas gingivalis is regulated by the redox-sensing transcription activator oxyR. Microbiology. 2006;152:955–966. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourne DO, Aruni W, Roy F, et al. The role of vima in cell surface biogenesis in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology. 2010;156:2180–2193. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038331-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourne D, Wilson Aruni A, Dou Y, et al. Vima dependent modulation of secretome in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:420–435. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potempa J, Sroka A, Imamura T, Travis J. Gingipains, the major cysteine proteinases and virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis: structure, function and assembly of multidomain protein complexes. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:397–407. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. pp. 7.32–7.34. [Google Scholar]

- Tribble GD, Kerr JE, Wang BY. Genetic diversity in the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis: molecular mechanisms and biological consequences. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:607–620. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Fletcher HM. Inactivation of Vimf, a putative glycosyltransferase gene downstream of Vime, alters glycosylation and activation of the gingipains in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Infect Immun. 2005a;73:3971–3982. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3971-3982.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Sandberg L, Fletcher HM. Altered gingipain maturation in VimA- and VimE-defective isogenic mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2005b;73:1357–1366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1357-1366.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Roy F, Zhan W, Sheets SM, Sandberg L, Fletcher HM. Vima is part of the maturation pathway for the major gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. Microbiology. 2006;152:3383–3389. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanterpool E, Aruni AW, Roy F, Fletcher HM. Regt can modulate gingipain activity and response to oxidative stress in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology. 2010;156:3065–3072. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]