Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between thyroid hormone levels and sleep quality in community-dwelling men.

Methods

Among 5,994 men aged ≥65 years in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study, 682 had baseline thyroid function data, normal free thyroxine (FT4) (0.70 ≤ FT4 ≤ 1.85 ng/dL), actigraphy measurements, and were not using thyroid-related medications. Three categories of thyroid function were defined: subclinical hyperthyroid, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.55 mIU/L; euthyroid (TSH, 0.55 to 4.78 mIU/L); and subclinical hypothyroid (TSH >4.78 mIU/L). Objective (total hours of nighttime sleep [TST], sleep efficiency [SE], wake after sleep onset [WASO], sleep latency [SL], number of long wake episodes [LWEP]) and subjective (TST, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score) sleep quality were measured. The association between TSH and sleep quality was examined using linear regression (continuous sleep outcomes) and log-binomial regression (categorical sleep outcomes).

Results

Among the 682 men examined, 15 had subclinical hyperthyroidism and 38 had subclinical hypothyroidism. There was no difference in sleep quality between subclinical hypothyroid and euthyroid men. Compared to euthyroid men, subclinical hyperthyroid men had lower mean actigraphy TST (adjusted mean difference [95% confidence interval (CI)], −27.4 [−63.7 to 8.9] minutes) and lower mean SE (−4.5% [−10.3% to 1.3%]), higher mean WASO (13.5 [−8.0 to 35.0] minutes]), whereas 41% had increased risk of actigraphy-measured TST <6 hours (relative risk [RR], 1.41; 95% CI, 0.83 to 2.39), and 83% had increased risk of SL ≥60 minutes (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.65 to 5.14) (all P>0.05).

Conclusion

Neither subclinical hypothyroidism nor hyperthyroidism is significantly associated with decreased sleep quality.

Keywords: thyroid functions, subclinical hyperthyroidism, subclinical hypothyroidism, sleep quality, actigraphy, subjective sleep measures, MrOs study

INTRODUCTION

Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) of 16,533 people who did not report thyroid disease, goiter, or use of thyroid medications, the prevalence of subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism is 0.7 and 4.3%, respectively (1). In NHANES III study, the median (2.5th to 97.5th percentile) thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) concentration among all participants was 1.49 mIU/L (0.44 to 5.52 mIU/L). The TSH concentration increased with age, more so in women than in men: the median (2.5th to 97.5th percentile) TSH concentration was 1.67 mIU/L (0.55 to 4.89 mIU/L) for males aged 60 to 69 years, 1.99 mIU/L (0.45 to 11.64 mIU/L) for females aged 60 to 69 years, 1.88 mIU/L (0.45 to 8.72 mIU/L) for males aged 70 to 79 years, 2.0 mIU/L (0.46 to 12.97 mIU/L) for females aged 70 to 79 years, 1.99 mIU/L (0.33 to 7.75 mIU/L) for males ≥80 years of age, and 2.1 mIU/L (0.3 to 10.79 mIU/L) for females ≥80 years of age.

In the Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence Study, the prevalence of subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism among 24,337 subjects not taking thyroid medication was 0.9 and 8.5%, respectively (2). The higher prevalence of subclinical thyroid diseases in this population compared with the NHANES III study may be due to the fact that 28.2% of the participants in the Colorado study were ≥65 years of age, whereas only 10% of the general population of Colorado is in this age group (2).

In both subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, free thyroxine (FT4) and triiodothyronine concentrations are normal; however, in subclinical hyperthyroidism, serum TSH concentrations are low, whereas in subclinical hypothyroidism they are elevated. Subclinical thyroid diseases may have various health effects, including effects on cardiovascular and skeletal health, especially an increased risk of atrial fibrillation with subclinical hyperthyroidism (3).

Among 6,139 individuals over the age of 16 surveyed in the NHANES 2005–2006, the prevalence of physician-diagnosed insomnia was 1.2% (4). There are limited data regarding the associations between thyroid hormone abnormalities and sleep disturbance. Kraemer et al (5) studied the effects of hyperthyroxinemia induced by supraphysiologic dosing of levothyroxine (500 µg/day) in 13 healthy subjects for an 8-week period. Sleep architecture evaluated by polysomnography at baseline did not differ from that evaluated while the subjects were hyperthyroxinemic. Koehler et al (6) studied 7 patients with well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma undergoing levothyroxine withdrawal for radioactive iodine ablation therapy. They found no statistically significant difference in either subjective or objective sleep quality in these patients with short-term hypothyroidism. Using polysomnographic recordings, Ruíz-Primo et al (7) studied 9 patients with severe hypothyroidism. They found that although the patients were myxedematous, there was a complete absence or very low levels of slow wave sleep in patients >20 years of age.

To our knowledge, no community-based study has evaluated the association between subclinical thyroid diseases and sleep disturbances assessed both subjectively and objectively.

METHODS

Study Population

The MrOS is a prospective cohort study involving 5,994 community-dwelling men and designed to examine healthy aging and fracture risk. Eligible men were ≥65 years of age, ambulatory, and had not had bilateral hip replacement. Participants were enrolled from March 2000 to April 2002 at one of six U.S. clinical centers. Details of the MrOS study design and cohort have been previously reported (8,9). The Institutional Review Board at each clinical center approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Analytic Sample

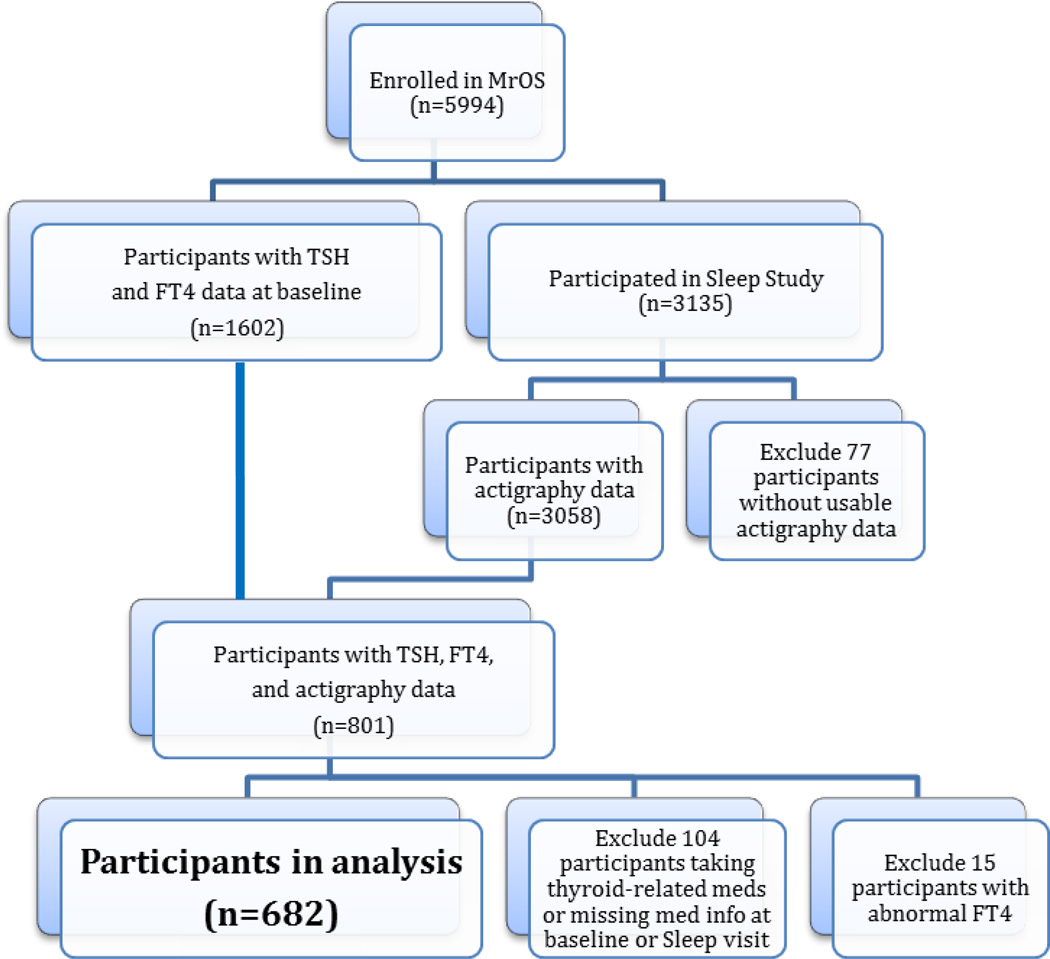

Among the 5,994 men enrolled in the MrOS study, a random sample of 1,602 had baseline measurements of TSH and FT4, whereas 3,135 subsequently participated in an ancillary study entitled Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men (MrOS Sleep Study), which occurred an average of 3.4 years after baseline samples were obtained. Of the 3,135 men at the sleep visit, 3,058 had usable wrist actigraphy measurements. A total of 801 men had baseline thyroid measures and complete actigraphy data at the subsequent sleep visit. A total of 15 men with abnormal FT4 (<0.70 or >1.85 ng/dL) and 104 men who were taking antithyroid medications or thyroid hormone supplements at either the baseline or the sleep visit or were missing this information were excluded. The remaining 682 men formed the analytic sample for our analysis of the association between thyroid function and sleep quality (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study Design

Thyroid Hormone Measurements

At baseline, serum was collected and archived at −120°C as described in previous publications (9,10). TSH was measured using a third-generation assay (Siemens Diagnostic, Deerfield, IL). The reference range for this assay is 0.55 to 4.78 mIU/L, with a coefficient of variation of 2.4% at 2.08 mIU/L. FT4 was measured with a competitive immunoassay (Siemens Diagnostics), with a reference range of 0.70 to 1.85 ng/dL and a coefficient of variation of 4.1% at 1.09 ng/dL. All assays were performed at the University of Minnesota Medical Center.

Wrist Actigraphy

Objective sleep quality was assessed using wrist actigraphy. The Octagonal Sleep Watch actigraph, or Sleep Watch-O (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc, Ardsley, NY), was used to estimate sleep/wake activity and was given to participants during the clinic visit along with instructions to wear the actigraph continuously on the nondominant wrist for a minimum of five consecutive 24-hour periods. The Sleep Watch-O actigraph contains a piezoelectric linear accelerometer (sensitive to 0.003 g and above) with a biomorph-ceramic cantilevered beam, a microprocessor, 32K RAM memory, and associated circuitry. Voltage generated each time the actigraph moves is gathered continuously and summarized over 1-minute epochs. Actigraphy data were collected for this study in 3 modes: zero crossing mode (ZCM), proportional integration mode (PIM), and time above threshold mode (TAT) (11). Data were scored using Action W-2 software (12), based on an algorithm developed at the University of California, San Diego for data collected in the PIM and TAT modes and on the Cole-Kripke algorithm for data collected in the ZCM mode (13,14). These algorithms calculate a moving average, which takes into account the activity levels immediately before and after the current minute to determine if the given time point should be coded as sleep or wake. The average of the sleep parameters over all nights was used in all analyses to minimize night-to-night variability. Interscorer reliability for scoring of this data was previously found to be high in our group (intraclass coefficient, 0.95) (15).

Actigraphy parameters used for analyses included: total hours of sleep per night (TST); sleep efficiency (SE; the percentage of time the participant spent sleeping while in bed); wake after sleep onset (WASO; a measure of sleep fragmentation which represents the number of minutes a participant was awake during a typical sleep period, after the initial onset of sleep of at least 20 minutes in duration); sleep latency (SL; the number of minutes it took for a participant to fall asleep from the time they reported getting into bed); and number of long wake episodes (>5 minutes awake at a time) while in bed (LWEP). Sleep diaries in which participants recorded when they went to bed and when lights were turned off were used to calculate sleep latency.

Subjective Sleep Measures

Subjective sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), data for which were obtained at the time of the sleep visit. The PSQI measures reported sleep patterns and sleep problems, including sleep quality, SL, SE, and daytime dysfunction. The PSQI is a 19-item questionnaire demonstrated to have high internal consistency (0.83), test-retest reliability (0.85), and diagnostic validity. A global sleep quality score derived from the PSQI can be used to index overall quality of sleep over the prior 1-week period. Global sleep quality scores are continuous (range, 0 to 21), with higher scores reflecting poorer sleep quality. A standard cut-point of PSQI >5 was used to define poor sleepers (16). The ESS measures daytime sleepiness, using a scale from 0 to 24, with higher scores representing more daytime sleepiness. This scale is a validated instrument, standard in sleep research. We used a standard cut-point of ESS >10 for excessive daytime sleepiness (17,18).

Other Measures

At the baseline examination, MrOS participants completed a questionnaire that asked about age, race/ethnicity, education, living arrangement, general health status, smoking status, alcohol use, and medical history. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) (19). To assess functional status, men were queried regarding 5 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Daily caffeine intake was assessed using the Block 98 semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (Block Dietary Data Systems, Berkeley, CA). Depression was assessed according to self-reported mood, using 1 question from the modified 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12 (SF-12) (20). Anxiety was also assessed using a question from the SF-12. Cognitive function was evaluated using the Teng Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS), with scores ranging from 0 to 100 and higher scores representing better cognitive function (21). Height (centimeters) was measured on Harpenden stadiometers and weight (kilograms) on standard balance beam or digital scales, with participants wearing light clothing without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kilograms per square meter. Participants were asked to bring all current medications with them to the clinic. All prescription medications were recorded by the clinics, and data were stored in an electronic medications inventory database (San Francisco Coordinating Center, San Francisco, CA) (22). Each medication was matched to its ingredient(s) based on the Iowa Drug Information Service Drug Vocabulary (College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). History of restless leg syndrome and history of sleep apnea were self-reported and not assessed until the sleep visit.

Statistical Analysis

Three thyroid function categories were created based on TSH and normal FT4 (FT4, 0.7 to 1.85 ng/dL): subclinical hyperthyroid (TSH <0.55 mIU/L), euthyroid (TSH 0.55 to 4.78 mIU/L), and subclinical hypothyroid (TSH >4.78 mIU/L). Characteristics of the men were compared across these 3 categories using either analyses of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests (continuous variables) or chi-square tests of homogeneity (categorical variables).

Each sleep outcome was analyzed both as a continuous and categorical variable. Dichotomized variables were based on consideration of the clinical relevance of values for older adults, validated cut-points, and comparability to prior MrOS sleep publications: poor SE (<70% versus ≥70%), greater nighttime wakefulness (WASO ≥90 minutes versus <90 minutes), prolonged SL (≥60 minutes versus <60 minutes), multiple LWEP (≥8 versus <8), poor sleeper based on PSQI >5, and excessive daytime sleepiness based on ESS >10. Total sleep time was categorized as <6 hours, 6 to 8 hours, and >8 hours based on clinical relevance and to determine whether there was a U-shaped association between total sleep time and thyroid function. Because the distribution of SL was skewed, this measure was log-transformed, with results back-transformed when analyzed as a continuous variable.

Least-squared-means linear regression was used to examine the adjusted association between the 3 thyroid function categories and continuous sleep outcomes, with results presented as adjusted mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). Linear regression was used to examine the association between continuous TSH and the continuous sleep outcomes, with results presented as beta (change in mean sleep) and 95% CI per SD decrease in TSH.

Log-binomial regression was used to model the association between the thyroid categories and categorical sleep outcomes, with results presented as relative risk (RR) and 95% CI for subclinical hyperthyroid men versus euthyroid men and for subclinical hypothyroid men versus euthyroid men (23). For those instances in which the log-binomial model did not converge, log-Poisson models, which provide consistent (but not fully efficient) estimates of the RR and its CI were used (24). Log-binomial regression was also used to examine the risk of poor sleep per SD decrease in continuous TSH (22,24).

Three sets of models were run to analyze the association between TSH and each sleep outcome: unadjusted, age-clinic adjusted, and multivariate-adjusted. Known or suspected determinants of thyroid function and the sleep parameters were examined for potential confounding. Unadjusted linear regression models were run to examine the association between each potential covariate and continuous TSH, and age-clinic adjusted linear regression models were run to examine each covariate’s association with the continuous sleep outcomes. Covariates with strong associations (P<.10) with TSH and/or most of the sleep outcomes in these models were included in the full multivariate models. Because of the numerous outcomes, one set of confounders was chosen for all multivariate models. The multivariate models were adjusted for age, clinic site, race, education, whether the patient lived alone or not, IADL impairment, history of diabetes, history of congestive heart failure (CHF), history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 3MS, and BMI.

Sensitivity analyses that included the 15 men with abnormal FT4 in the models were performed to determine whether inclusion of these men affected the results.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants

At baseline, the mean ± SD age of the 682 men was 72.9 ± 5.6 years, mean BMI was 27.5 ± 3.7 kg/m2, 91% of the men were Caucasian, and 88% reported good to excellent health (Table 1). The mean TSH for these men was 2.3 ± 1.4 mIU/L, and the median was 2.0 (interquartile range, 1.3 to 2.9) mIU/L. Mean FT4 was 0.98 ± 0.13 ng/dL. Over 90% of the men were classified as euthyroid, 6% were classified as subclinical hypothyroid, and only 2% were classified as subclinical hyperthyroid. At the sleep visit, the men slept an average of 6.4 ± 1.2 hours per night, as determined by actigraphy, with a mean SE of 78.1 ± 11.8%. It took the men an average of 31.5 ± 32.9 minutes to fall asleep, and they were awake an average of 78.0 ± 43.7 minutes after sleep onset. On average, the men had 7 episodes of being awake for more than 5 minutes during the night. About half of the men were identified as poor sleepers based on a PSQI score >5, and 14% had excessive daytime sleepiness based on an Epworth score >10. Compared to euthyroid men, men with subclinical hypothyroidism were older and had less education, were more likely to live alone, have an IADL impairment, have a history of diabetes, be depressed, and have a history of restless leg syndrome. Men with subclinical hyperthyroidism were older and more likely to be non-Caucasian than euthyroid men. A smaller percentage of the subclinical hyperthyroid men lived alone, and they had a lower PASE score. Men with subclinical hyperthyroidism were also more likely to have a history of CHF and COPD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 682 Participants by Thyroid Hormone Status

| Thyroid Hormone Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall Cohort (N = 682) |

Subclinical Hyperthyroidism (TSH<0.55 mIU/L) (n =15) |

Euthyroidism (TSH 0.55–4.78 mIU/L) (n =629) |

Subclinical Hypothyroidism (TSH>4.78 mIU/L) (n =38) |

P value |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 72.9 ± 5.6 | 74.1 ± 4.8 | 72.7 ± 5.5 | 75.3 ± 6.8 | 0.01 |

| Caucasian race, n (%) | 620 (90.9) | 12 (80.0) | 573 (91.1) | 35 (92.1) | 0.32 |

| College education or greater, n (%) | 379 (55.6) | 8 (53.3) | 352 (56.0) | 19 (50.0) | 0.76 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 80 (11.7) | 1 (6.7) | 71 (11.3) | 8 (21.1) | 0.16 |

| Excellent or good health status, n (%) | 599 (88.0) | 13 (86.7) | 556 (88.5) | 30 (79.0) | 0.21 |

| PASE score, mean ± SD | 155.4 ± 67.5 | 117.0 ± 64.6 | 156.2 ± 67.6 | 157.7 ± 62.6 | 0.08 |

| IADL impairment, n (%) | 109 (16.0) | 2 (13.3) | 98 (15.6) | 9 (23.7) | 0.40 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 17 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.5) | 1 (2.6) | 0.82 |

| Alcohol intake, drinks/wk, mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 7.4 | 4.2 ± 4.7 | 4.7 ± 7.6 | 4.1 ± 4.7 | 0.65 |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day, mean ± SD | 225.6 ± 237.2 | 203.4 ± 246.4 | 227.3 ± 237.3 | 206.7 ± 236.5 | 0.80 |

| History of hyperthyroidism, n (%) | 7 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.56 |

| History of hypothyroidism, n (%) | 8 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.1) | 1 (2.6) | 0.64 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 68 (10.0) | 1 (6.7) | 62 (9.9) | 5 (13.2) | 0.73 |

| History of CHF, n (%) | 27 (4.0) | 2 (13.3) | 24 (3.8) | 1 (2.6) | 0.16 |

| History of COPD, n (%) | 70 (10.3) | 4 (26.7) | 61 (9.7) | 5 (13.2) | 0.08 |

| 3MS score (range 0–100), mean ± SD | 94.0 ± 5.1 | 93.3 ± 6.5 | 94.0 ± 5.1 | 94.3 ± 4.4 | 0.83 |

| Depression in last 4 weeks, n (%) | 30 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (4.1) | 4 (10.5) | 0.12 |

| Anxiety in last 4 weeks, n (%) | 34 (5.0) | 2 (13.3) | 30 (4.8) | 2 (5.3) | 0.32 |

| History of restless leg syndrome, n (%)* | 15 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (1.9) | 3 (7.9) | 0.04 |

| History of sleep apnea, n (%)* | 41 (6.1) | 1 (6.7) | 38 (6.2) | 2 (5.3) | 0.97 |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | 32 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.26 |

| Benzodiazepine use, n (%) | 20 (2.9) | 1 (6.7) | 18 (2.9) | 1 (2.6) | 0.68 |

| Sleep medication use, n (%) | 5 (0.8) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 174.5 ± 6.9 | 174.5 ± 7.0 | 174.4 ± 6.9 | 176.1 ± 6.8 | 0.34 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 84.0 ± 13.0 | 83.3 ± 18.2 | 83.9 ± 12.9 | 84.5 ± 12.7 | 0.95 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 27.5 ± 3.7 | 27.2 ± 4.5 | 27.6 ± 3.7 | 27.2 ± 3.3 | 0.75 |

| Actigraphy Sleep Measures | |||||

| Nightly sleep duration, hours, mean ± SD | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 1.1 | 0.36 |

| Nightly sleep duration, n (%) | 0.58 | ||||

| < 6 hours | 225 (33.0) | 7 (46.7) | 207 (32.9) | 11 (29.0) | |

| 6–8 hours | 407 (59.7) | 6 (40.0) | 377 (59.9) | 24 (63.2) | |

| > 8 hours | 50 (7.3) | 2 (13.3) | 45 (7.2) | 3 (7.9) | |

| Sleep efficiency, %, mean ± SD | 78.1 ± 11.8 | 73.8 ± 19.2 | 78.2 ± 11.5 | 79.5 ± 12.0 | 0.27 |

| Sleep efficiency < 70%, n (%) | 121 (17.7) | 4 (26.7) | 111 (17.7) | 6 (15.8) | 0.63 |

| Wake after sleep onset, min, mean ± SD | 78.0 ± 43.7 | 91.8 ± 63.4 | 78.2 ± 43.9 | 69.2 ± 28.1 | 0.21 |

| Wake after sleep onset ≥ 90 min, n (%) | 215 (31.5) | 7 (46.7) | 198 (31.5) | 10 (26.3) | 0.35 |

| Sleep latency, min, mean ± SD | 31.5 ± 32.9 | 45.4 ± 67.4 | 31.0 ± 30.6 | 33.0 ±46.7 | 0.57 |

| Sleep latency ≥ 60 min, n (%) | 75 (11.0) | 3 (20.0) | 67 (10.7) | 5 (13.2) | 0.47 |

| Long wake episodes, number, mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 3.2 | 7.8 ± 4.2 | 6.9 ± 3.2 | 6.3 ± 2.9 | 0.30 |

| At least 8 long wake episodes, n (%) | 231 (33.9) | 6 (40.0) | 215 (34.2) | 10 (26.3) | 0.54 |

| Subjective Sleep Measures | |||||

| Nightly sleep duration, hours, mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 0.07 |

| Nightly sleep duration, n (%) | 0.24 | ||||

| < 6 hours | 84 (12.3) | 4 (26.7) | 75 (11.9) | 5 (13.2) | |

| 6–8 hours | 565 (83.0) | 11 (73.3) | 521 (83.0) | 33 (86.8) | |

| > 8 hours | 32 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PSQI score (range 0–21), mean ± SD | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 6.9 ± 5.1 | 5.6 ± 3.2 | 6.0 ± 3.6 | 0.26 |

| Poor sleeper (PSQI score > 5), n (%) | 315 (46.2) | 6 (40.0) | 290 (46.1) | 19 (50.0) | 0.80 |

| Epworth score (range 0–24), mean ± SD | 6.1 ± 3.8 | 5.9 ± 3.8 | 6.1 ± 3.8 | 6.1 ± 3.3 | 0.97 |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth score > 10), n (%) | 95 (14.0) | 2 (13.3) | 89 (14.2) | 4 (10.5) | 0.82 |

| Thyroid Hormone Measures | |||||

| TSH, mIU/L, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Free thyroxine, ng/dL, mean ± SD | 0.98 ± 0.13 | 1.07 ± 0.15 | 0.99 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | <0.0001 |

gathered at the Sleep visit

P values are from ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for skewed continuous variables.P values for categorical data are from a χ2test for homogeneity.

3MS = Teng Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; BMI = Body Mass Index; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; SD = Standard Deviation; TSH = Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

Association Between Thyroid Function and Continuous Sleep Measures

In unadjusted analyses, there were no significant differences in mean sleep quality for euthyroid and subclinical hypothyroid men, although the mean WASO appeared to be lower for subclinical hypothyroid men than for euthyroid men, with a mean difference of −9.1 (95% CI, −23.4 to 5.2) minutes (Table 2). Compared with euthyroid men, men with subclinical hyperthyroidism had a lower mean actigraphy TST (mean difference [95% CI], −26.9 [−63.9 to 10.0] minutes), lower mean SE (mean difference [95% CI], −4.4% [−10.4 to 1.6%]), higher mean WASO (mean difference [95% CI], 13.6 [−9.7 to 36.0] minutes), longer mean SL (mean difference [95% CI], 6.1 [−2.0 to 18.8] minutes), more LWEPs (mean difference [95% CI], 0.8 [−0.8 to 2.5]), lower mean self-reported TST (mean difference [95% CI], −43.7 [−80.6 to −6.8] minutes), and higher mean PSQI (mean difference [95% CI], 1.3 [−0.4 to 3.0]). Only the self-reported TST finding was statistically significant (P = .02). Results remained virtually unchanged after multivariate adjustment, except that the difference in mean WASO between the subclinical hypothyroid men and euthyroid men was slightly greater with multivariate adjustment (mean difference [95% CI], −12.9 [−26.7 to 0.8] minutes) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sleep Measures by Thyroid Hormone Status

| Mean (95% CI) by Thyroid Hormone Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Measure | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism (TSH<0.55 mIU/L) (n = 15) |

Euthyroidism (TSH 0.55–4.78 mIU/L) (n = 629) |

Subclinical Hypothyroidism (TSH>4.78 mIU/L) (n = 38) |

P value for trend |

| Objective Measures | ||||

| Nightly sleep duration, hours | ||||

| Unadjusted | 6.0 (5.4, 6.6) | 6.4 (6.3, 6.5) | 6.4 (6.0, 6.8) | 0.46 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 5.9 (5.3, 6.5) | 6.4 (6.3, 6.5) | 6.4 (6.0, 6.8) | 0.43 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 6.0 (5.4, 6.6) | 6.4 (6.3, 6.5) | 6.4 (6.0, 6.8) | 0.37 |

| Sleep efficiency, % | ||||

| Unadjusted | 73.8 (67.8, 79.7) | 78.2 (77.2, 79.1) | 79.5 (75.8, 83.3) | 0.16 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 73.2 (67.3, 79.1) | 78.1 (77.2, 79.1) | 79.9 (76.2, 83.7) | 0.09 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 73.6 (67.8, 79.3) | 78.1 (77.2, 79.0) | 80.4 (76.8, 84.1) | 0.06 |

| Wake after sleep onset, min | ||||

| Unadjusted | 91.8 (69.7, 113.9) | 78.2 (74.8, 81.6) | 69.1 (55.3, 83.0) | 0.08 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 93.2 (71.3, 115.0) | 78.3 (74.9, 81.7) | 67.1 (53.3, 80.9) | 0.04 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 91.9 (70.7, 113.2) | 78.4 (75.2, 81.7) | 65.5 (52.1, 78.8) | 0.02 |

| Sleep latency, min | ||||

| Unadjusted | 28.4 (19.0, 42.5) | 22.3 (21.0, 23.7) | 20.7 (16.1, 26.7) | 0.26 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 29.5 (19.8, 44.1) | 22.3 (21.0, 23.7) | 20.7 (16.0, 26.6) | 0.21 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 29.3 (19.6, 43.8) | 22.3 (21.0, 23.7) | 20.6 (16.0, 26.6) | 0.22 |

| Long wake episodes, number | ||||

| Unadjusted | 7.8 (6.2, 9.4) | 6.9 (6.7, 7.2) | 6.3 (5.3, 7.3) | 0.13 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 7.9 (6.3, 9.5) | 6.9 (6.7, 7.2) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.2) | 0.07 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 7.8 (6.3, 9.4) | 6.9 (6.7, 7.2) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.2) | 0.07 |

| Subjective Measures | ||||

| Nightly sleep duration, hours | ||||

| Unadjusted | 6.1 (5.5, 6.7) | 6.9 (6.8, 6.9) | 6.9 (6.5, 7.2) | 0.18 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 6.1 (5.5, 6.7) | 6.9 (6.8, 7.0) | 6.9 (6.5, 7.3) | 0.15 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 6.1 (5.5, 6.7) | 6.9 (6.8, 6.9) | 6.9 (6.5, 7.3) | 0.11 |

| PSQI score (range 0–21) | ||||

| Unadjusted | 6.9 (5.3, 8.6) | 5.6 (5.4, 5.9) | 6.0 (5.0, 7.1) | 0.80 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 7.0 (5.3, 8.6) | 5.6 (5.4, 5.9) | 5.9 (4.9, 6.9) | 0.63 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 7.0 (5.4, 8.6) | 5.7 (5.4, 5.9) | 5.7 (4.7, 6.7) | 0.38 |

| Epworth score (range 0–24) | ||||

| Unadjusted | 5.9 (4.0, 7.8) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.4) | 6.1 (4.9, 7.3) | 0.97 |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 6.0 (4.1, 7.9) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.4) | 6.1 (4.9, 7.3) | 0.99 |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 5.9 (4.0, 7.8) | 6.1 (5.9, 6.4) | 6.0 (4.8, 7.2) | 0.90 |

Adjusted for age, clinic, race, education, lives alone, IADL impairment, history of diabetes, history of CHF, history of COPD, 3MS score, and BMI.

3MS = Teng Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; BMI = Body Mass Index; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure; CI = Confidence Interval; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TSH = Thyroid Stimulating Hormone.

Sleep quality worsened with lower values of TSH, although results were significant only for WASO (P = .04): for each standard deviation decrease in TSH, the adjusted mean actigraphy TST decreased by 4.4 minutes (95% CI, −10.0 to 0.9 minutes), mean SE decreased by 0.7% (95% CI, −1.6 to 0.1%), mean WASO increased 3.3 minutes (95% CI, 0.1 to 6.5 minutes), median SL increased 3% (95% CI, −3 to 9%), mean number of LWEPs increased by 0.2 (95% CI, 0.0 to 0.5), and mean self-reported TST decreased by 2.9 minutes (95% CI, −8.4 to 2.6 minutes) (data not shown).

The associations between thyroid function and the continuous sleep measures were unchanged by including the 15 men with abnormal FT4 in the models.

Association Between Thyroid Function and Categorical Sleep Measures

Sleep quality was similar for the subclinical hypothyroid and euthyroid men in unadjusted analyses when the sleep measures were analyzed categorically (Tables 1 and 3). In contrast, men with subclinical hyperthyroidism had worse objective sleep quality than euthyroid men, although none of the differences were statistically significant: a higher percentage of subclinical hyperthyroid men slept fewer than 6 hours (46.7% versus 32.9% for subclinical hyperthyroid versus euthyroid men) or more than 8 hours per night (13.3% versus 7.2%; P = .27), a higher percentage had <70% SE (26.7% versus 17.7%; P = .37), a higher percentage had at least 90 minutes of WASO (46.7% versus 31.5%; P = .21), about twice as many took at least an hour to fall asleep (20.0% versus 10.7%; P = .25), and a higher percentage had at least 8 episodes of awakening for more than 5 minutes during the night (40.0% versus 34.2%; P = .64). A higher percentage of men with subclinical hyperthyroidism reported sleeping less than 6 hours per night (26.7% versus 11.9%), but none of these men reported sleeping more than 8 hours per night (P = .17). Compared with 46.1% of euthyroid men who were classified as poor sleepers based on a PSQI >5, half of subclinical hypothyroid men (P = .64) and 40.0% of subclinical hyperthyroid men (P = .64) were classified as poor sleepers. Euthyroid men were most likely and subclinical hypothyroid men were least likely to report excessive daytime sleepiness.

Table 3.

Risk of Poor Sleep by Thyroid Hormone Status

| Relative Risk (95% CI) by Thyroid Hormone Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Measure | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism (TSH<0.55 mIU/L) (n = 15) |

Euthyroidism (TSH 0.55–4.78 mIU/L) (n = 629) |

Subclinical Hypothyroidism (TSH>4.78 mIU/L) (n = 38) |

| Objective Measures | |||

| Nightly sleep duration < 6 hours* | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.52 (0.91, 2.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.89 (0.54, 1.46) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 1.44 (0.87, 2.38) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.83 (0.50, 1.38) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 1.41 (0.83, 2.39) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.82 (0.50, 1.34) |

| Nightly sleep duration > 8 hours* | |||

| Unadjusted | 2.34 (0.68, 8.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.04 (0.35, 3.14) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 1.97 (0.57, 6.81) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.87 (0.28, 2.66) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 3.03 (0.87, 10.53) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.84 (0.27, 2.60) |

| Sleep efficiency < 70% | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.51 (0.64, 3.56) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.89 (0.42, 1.90) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 1.60 (0.68, 3.74) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.82 (0.39, 1.74) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 1.41 (0.58, 3.42) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.80 (0.36, 1.75) |

| Wake after sleep onset ≥ 90 min | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.48 (0.85, 2.58) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.44) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 1.63 (0.95, 2.80) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.28) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 1.62 (0.95, 2.76) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.76 (0.43, 1.35) |

| Sleep latency ≥ 60 min | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.88 (0.67, 5.30) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.23 (0.53, 2.88) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 2.20 (0.78, 6.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.20 (0.52, 2.80) |

| Multivariate-adjusted* | 1.83 (0.65, 5.14) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.10 (0.45, 2.69) |

| Long wake episodes ≥ 8 | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.17 (0.62, 2.20) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.77 (0.45, 1.32) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 1.34 (0.71, 2.51) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.74 (0.43, 1.26) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 1.45 (0.75, 2.78) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.69 (0.41, 1.19) |

| Subjective Measures | |||

| Nightly sleep duration < 6 hours* | |||

| Unadjusted | 2.12 (0.89, 5.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.05 (0.45, 2.43) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 2.18 (0.91, 5.19) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.02 (0.44, 2.40) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 1.66 (0.65, 4.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.96 (0.41, 2.28) |

| Nightly sleep duration > 8 hours* | |||

| Unadjusted | N/A | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | N/A | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | N/A | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Poor sleeper (PSQI score > 5) | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.87 (0.46, 1.62) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.51) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 0.94 (0.50, 1.75) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.05 (0.75, 1.46) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 0.86 (0.48, 1.54) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.39) |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth score> 10) | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 (0.25, 3.47) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.74 (0.29, 1.91) |

| Age+clinic-adjusted | 0.92 (0.26, 3.32) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.78 (0.30, 2.02) |

| Multivariate-adjusted† | 0.74 (0.19, 2.85) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.67 (0.26, 1.73) |

Compared with 6–8 hours.

Adjusted for age, clinic, race, education, lives alone, IADL impairment, history of diabetes, history of CHF, history of COPD, 3MS score, and BMI.

N/A: unable to determine RR since no one in the hyperthyroid or hypothyroid groups reported sleeping more than 8 hours per night.

3MS = Teng Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; BMI = Body Mass Index; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure; CI = Confidence Interval; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TSH = Thyroid Stimulating Hormone.

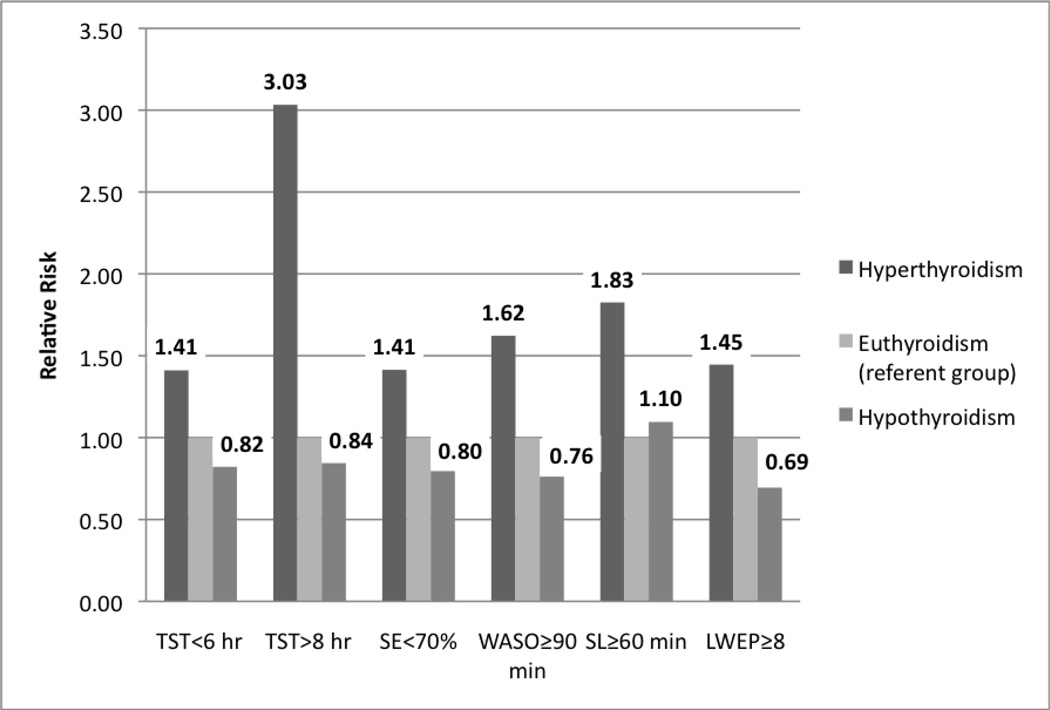

The risk of poor sleep for the subclinical hypothyroid group was not significantly different from that of the euthyroid group in adjusted analyses (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Although the multivariate-adjusted RR for sleeping more than 8 hours for men with subclinical hyperthyroidism compared with euthyroid men was 3.03 (95% CI, 0.87 to 10.53), this difference was not statistically significant, nor was the multivariate adjusted RR for requiring at least 1 hour to fall asleep (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.65 to 5.14).

Figure 2.

Risk of Objectively-Measured Poor Sleep by Thyroid Hormone Status

Results have been adjusted for age, clinic, race, education, lives alone, IADL impairment, history of diabetes, history of CHF, history of COPD, 3MS score, and BMI.

The relative risk for the hyperthyroid and hypothyroid groups was not significantly different from that of the euthyroid group (all 95% confidence intervals included 1.0).

3MS = Teng Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; BMI = Body Mass Index; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LWEP = Long Wake Episodes; SE = Sleep Efficiency; SL = Sleep Latency; TST = Total Sleep Time.

The risk of objectively measured poor sleep increased with lower values of TSH, although only the WASO (P = .02) and LWEP (P = .006) results differed significantly: for each standard deviation decrease in TSH, the multivariate-adjusted risk of actigraphy TST <6 hours increased 7% (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.19), the risk of actigraphy TST >8 hours decreased 12% (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.09), the risk of SE <70% increased 7% (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.27), the risk of WASO ≥90 minutes increased 16% (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.32), the risk of SL ≥60 minutes increased 7% (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.34), and the risk of ≥8 LWEPs increased 19% (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.34).

The associations between thyroid function and the categorical sleep measures were unchanged by including the 15 men with abnormal FT4 in the models.

DISCUSSION

Few men in this older, community-dwelling cohort met standard criteria for subclinical hyper- or hypothyroidism, even though the prevalence in our study (2% for subclinical hyperthyroidism and 6% for subclinical hypothyroidism) was higher than the prevalence of 0.7% for subclinical hyperthyroidism and 4.3% for subclinical hypothyroidism reported by NHANES III (1). This may explain why our study showed no statistically significant differences in either subjective or objective sleep quality between subclinical hypothyroid men and euthyroid men. Compared with euthyroid men, subclinical hyperthyroid men had less TST measured by actigraphy and had increased SL. Although some of these differences were large and may be clinically significant, the differences were not statistically significant in this study, possibly due to the small number of men in subclinical hyperthyroid group.

Limited previous studies showed no difference in sleep quality between hyperthyroid and hypothyroid patients compared with euthyroid subjects (5,6). Our findings regarding subclinical thyroid diseases were consistent with these previous reports.

Because both insomnia and subclinical thyroid disorders are common, it is not rare that a clinician will see a patient suffering from insomnia and a screening laboratory evaluation will reveal subclinical hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. In this scenario, it is not clear whether the subclinical thyroid disease is the cause of insomnia or whether the subclinical thyroid disease should be treated to remedy the insomnia. Our data suggest that subclinical thyroid disorders are not strongly associated with insomnia.

The strength of our study is that we were able to utilize objective sleep data for community-dwelling older men and correlate these data with thyroid status. In addition, these men were generally healthy, with no preexisting diagnosis of sleep disorders, and they were not selected based on sleep complaints, thereby enhancing the generalizability of these results.

The limitations of our study include the small number of subjects, especially in the subclinical hyperthyroid group. On the other hand, using the NHANES prevalence of 0.7% for subclinical hyperthyroidism in the U.S. population, we would need over 10,000 subjects to achieve 80% power for detecting a mean difference of 24 minutes for actigraphy total sleep duration for euthyroid men versus men with subclinical hyperthyroidism. As sleep studies are labor-intensive and costly, it would be unrealistic to design a community-based study with adequate power to examine the association between subclinical thyroid disease and quality of sleep. The other limitation of our study is that the thyroid hormone levels were measured on average 3.4 years prior to the sleep study; the thyroid hormone status may have changed by the time these subjects underwent the sleep evaluation. The fact that 16 men (excluded from this study) were taking thyroid medication at the sleep visit but not at baseline indicates that those who developed either overt hypo- or hyperthyroidism between these 2 visits were most likely not included in this study. On the other hand, some men with subclinical hypo- or hyperthyroidism at baseline may have normalized their TSH by the time of the sleep visit, and we cannot exclude the possibility that those men were erroneously categorized as subclinical hypo- or hyperthyroid for our analyses. The participants in this analysis were older men, and these results may not apply to other population groups, such as women or younger men.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the association between subclinical thyroid diseases and the quality of sleep among community-dwelling subjects not taking thyroid-related medications. Our data suggest no statistically significant differences exist between subclinical thyroid diseases and subjective or objective sleep disturbance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The MrOS study is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The following institutes provided support for this work: the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute on Aging, the National Center for Research Resources, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under grant numbers U01 AR45580, U01 AR45614, U01 AR45632, U01 AR45647, U01 AR45654, U01 AR45583, U01 AG18197, U01-AG027810, and UL1TR000128. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute provided funding for the MrOS Sleep ancillary study "Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men" under the following grant numbers: R01 HL071194, R01 HL070848, R01 HL070847, R01 HL070842, R01 HL070841, R01 HL070837, R01 HL070838, and R01 HL070839.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FT4

free thyroxine

- IADL

instrumental activity of daily living

- LWEP

long wake episodes

- MrOS

Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- RR

relative risk

- SE

sleep efficiency

- SL

sleep latency

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- TST

total hours of nighttime sleep

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489–499. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway C. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526–534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1142–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraemer S, Danker-Hopfe H, Pilhatsch M, Bes F, Bauer M. Effects of supraphysiological doses of levothyroxine on sleep in healthy subjects: a prospective polysomnography study. J Thyroid Res. 2011;2011:420580. doi: 10.4061/2011/420580. [Epub July 7, 2011]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koehler C, Ginzkey C, Kleinsasser NH, Hagen R, Reiners C, Verburg FA. Short-term severe thyroid hormone deficiency does not influence sleep parameters. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:253–258. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruíz-Primo E, Jurado JL, Solís H, Maisterrena JA, Fernández-Guardiola A, Valverde C. Polysomnographic effects of thyroid-hormones in primary myxedema. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;53:559–564. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOs) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOs) study—a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Comtemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waring AC, Harrison S, Samuels MH, et al. Thyroid function and mortality in older men: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:862–870. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motionlogger® User’s Guide. Ardsley, NY: Act Millennium, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Action-W User’s Guide, Version 2.0. Ardsley, NY: Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jean-Louis G, Kripke DF, Mason WJ, Elliot JA, Youngstedt SD. Sleep estimation from wrist movement quantified by different actigraphic modalities. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;105:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep. 1992;15:461–469. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Gehrman PR, Schneider JL, Pedula KL, Stone KL. Actigraphy scoring reliability in the study of osteoporotic fractures. Sleep. 2005;28:1599–1605. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.12.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johns MW. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the Epworth sleepiness scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): Development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores. 3rd ed. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, Wallace RB, Carbonin PU. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:301–305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]