Abstract

CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) αβ T cells are legitimate components of the normal immune system. However, they are poorly understood and largely ignored by immunologists because of their historical association with the lymphoproliferation that occurs in mice (lpr and gld) and humans (ALPS patients) with impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis where they are considered abnormal T cells. We believe that the traditional view that DN T cells that cause lymphoproliferation (hereafter referred to as lpr DN T cells) are CD4 and CD8 T cells that lost their coreceptor, conceived more than two decades ago, is flawed and that conflating lpr DN T cells with DN T cells found in normal immune system (hereafter referred to as nDN T cells) is unnecessarily dampening interest of this potentially important cell type. To begin rectifying these misperceptions, we will revisit the traditional view of lpr DN T cells and show that it does not hold true in light of recent immunological advances. In lieu of it, we offer a new model proposing that Fas-mediated apoptosis actively removes normally existing DN T cells from the periphery and that impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis leads to accumulation of these cells rather than de novo generation of DN T cells from activated CD4 or CD8 T cells. By doing so, we hope to provoke a new discussion that may lead to a consensus about the origin of lpr DN T cells and regulation of their homeostasis by the Fas pathway and reignite wider interest in nDN T cells.

Introduction

Several immune cells have undergone through periods early on after their discovery when their significance and legitimacy were questioned or outright dismissed. Case in point, lymphocytes as whole were described by O.A. Trowel in 1958 as “a poor sort of cell, characterized by mostly negative attributes: small in size, with especially little cytoplasm, unable to multiply, dying on the least provocation, surviving in vitro for only a few days, living in vivo for perhaps a few weeks”. Following his accurate phenotypic description of lymphocytes, Trowel went on to question their significance: “It must be regretfully concluded, however, that the office of this Cinderella cell is still uncertain.1” Likewise, suppressor/regulatory T cells were disdained for rather a lengthy period before they re-emerged as essential regulators of immune responses (reviewed in ref.2). In this perspective, we discuss the ongoing vilification of nDN αβ T cells that had begun more than three decades ago, its negative effects on understanding their pathophysiologic roles, and suggest steps that, if taken, might lead to clarification of the misperceptions of nDN T cells and their embrace as legitimate components of the immune system.

A major reason behind the limited interest in DN T cells, in our opinion, is related to their historical association with the lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly that occur in the lpr (lymphoproliferation) and gld (generalized lymphoproliferation) mice. This began in 1976, when mice carrying the lpr mutation were developed serendipitously by Murphy and Roth at Jackson Laboratory3 while investigating genes regulating development of lupus-like disease in predisposed mouse strains. They observed massive T cell lymphoproliferation in a substrain of MRL mice at the 12th generation of inbreeding that they referred to as MRL/1 (lpr/lpr). In 1984, another recessive mutation that leads to an lpr-like phenotype was developed and designated the gld4 mutation. The lymphoproliferation in lpr and gld mice was subsequently found to be due to massive accumulation of DN T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs by Morse et al.5 in 1982, which was subsequently confirmed by Davidson and coworkers6 in 1986. A phenotypically similar human disease was described by Sneller et al.7 in 1992 and termed autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndromes (ALPS) by Fisher et al.8 in 1995. The origin of DN T cells associated with this phenotype, however, remains controversial even though impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis has been identified more than two decades ago9, 10 (discussed in detail below) as the cause of their accumulation. We believe that the traditional view that DN T cells that cause lymphoproliferation (hereafter referred to as lpr DN T cells) are CD4 and CD8 T cells that lost their coreceptor, conceived more than two decades ago, is flawed and that conflating lpr DN T cells with DN T cells found in normal immune system (hereafter referred to as nDN T cells) is unnecessarily dampening interest of this potentially important cell type. To begin rectifying these misperceptions, we will revisit the traditional view of lpr DN T cells and show that it does not hold true in light of recent immunological advances. In lieu of it, we offer a new model proposing that Fas-mediated apoptosis actively removes normally existing DN T cells from the periphery and that impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis leads to accumulation of these cells rather than de novo generation of DN T cells from activated CD4 or CD8 T cells. By doing so, we hope to provoke a new discussion that may lead to a consensus about the origin of lpr DN T cells and regulation of their homeostasis by the Fas pathway and reignite wider interest in nDN T cells.

Why revisiting the origin of lpr DN T cells?

We believe that clear understanding of the origin of lpr DN T cells is critical for elucidating their relationship to nDN T cells and other T cells and gaining insights into two other related and similarly poorly understood phenomena. The first phenomenon is that predominance of DN T cells is limited to the lymphoproliferation caused by impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis but not lymphoproliferations caused by other immunological defects. For example, whereas genetic deletion of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim leads to T cell lymphoproliferation in response to chronic viral infections, the lymphoproliferation is predominated by CD8 T cells11. Likewise, the lymphoproliferation caused by CTLA4 deficiency12 or scurfy mutation13 are predominated by CD4 and CD8 T cells, but not DN T cells. Thus, DN T cell accumulation is not a general consequence of impaired apoptosis, but is tightly associated with defective Fas pathway. Understanding the underlying mechanism of this unique association might lead to novel insights into the physiologic function of the Fas pathway. It may also lead to new insight into the second phenomenon, which is the ability of the lpr and gld mutations to completely protect NOD mice from developing autoimmune diabetes14, 15 and to attenuate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis16, 17. In addition, both regulatory18, 19 and pathogenic20 functions have been attributed to lpr DN T cells and understanding their functions might lead to better understanding of nDN T cells and their relationship to the lpr DN T cells. For these reasons, we have devoted the majority of this perspective to revisit validity of the traditional view that lpr DN T cells are abnormal T cells and discuss viable alternative explanations afforded by recent immunological advances.

The unique phenotype of lpr DN T cells initiated their bad rap as abnormal T cells

lpr DN T cells displayed a peculiar phenotype. Unlike CD4 and CD8 single positive (SP) T cells, lpr DN T cells have a poor proliferative capacity and do not produce IL-2 upon TCR stimulation.21, 22 Furthermore, lpr DN T cells express B220, which is the B cell isoform of CD45.22 These peculiar characteristics of lpr DN T cells, besides the unknown identity of the lpr and gld mutations at the time, led to the currently widely held view that lpr DN T cells are abnormal or unusual T cells22. Intriguingly, this notion, which was developed more than a decade ago, has not been revisited despite significant new evidence questioning its validity. In addition, lpr DN T cells, which have been in the lime-light for decades have overshadowed nDN T cells found in the normal immune system of mice and humans. Consequently, nDNT cells are often overlooked and confused with lpr DN T cells, dampening interest in them as legitimate components of the immune system.

Impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis in lpr and gld mice identifies the cause of DN T cell lymphoproliferation but not their origin

The Fas pathway, the prototypical extrinsic death pathway, was discovered in 1989.23 Engagement of the Fas receptor by its ligand (FasL) mediates apoptotic signalling that leads to DNA fragmentation and T cell death. Identification of the lpr and gld mutations as loss-of-function point mutations in the genes encoding Fas and FasL in 1992 and 1993, respectively, established impaired apoptosis as the cause of T cell lymphoproliferation in mutant mice.9, 10 It failed, however, to provide a convincing explanation for why the lymphoproliferation is predominated by DN T cells. In other words, it has been puzzling why DN T cells, which constitute less than 5% of αβ T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs, gradually increase, reaching up to more than 80% of T cells in the periphery of mutant mice. In addition, the increase in the frequency of DN T cells is due to massive increase in their absolute numbers and not due to decreases in absolute numbers of CD4 and CD8 T cells, which also increased exponentially in mutant mice. The dysregulation of DN T cells homeostasis is also limited to the secondary lymphoid organs (spleen and lymph nodes) as there are no detectable alterations in DN or single positive CD4 or CD8 T cell homeostasis in the thymus or the gut epithelium of mutant mice.24 Consequently, given the rarity of nDN T cells in the normal peripheral lymphoid organs, attention to understanding the source(s) of accumulated DN T cells was conveniently directed to the effects of the mutations on peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cells. These efforts led to the current traditional view that spontaneously activated CD8 and CD4 T cells in mutant mice fail to undergo activation induced cell death (AICD), downregulate their co-receptors, and persist as DN T cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. DN T cell lymphoaccumulation in mice with impaired Fas pathway is limited to secondary lymphoid organs.

lpr and gld mutations cause massive expansion of DN T cells in the peripheral lymphoid organs (spleen and lymph nodes) without affecting DN T cell homeostasis in the thymus, kidney (not shown) or the gut epithelium.

Revisiting the traditional view that lpr DN T cell accumulation is due to downregulation of coreceptors by persisting CD8 and CD4 T cells

The traditional view that lpr DN T cells are CD4 or CD8 T cells that downregulate their coreceptors and persist as DN T cells was based on a number of key observations. One of these is the hypomethylation of the gene loci encoding the CD8 coreceptor, which indicated previous expression.25 The paradigm at the time was that immature TCRαβ+CD8+CD4+ double positive (DP) thymic precursors can only give rise to mature CD4 or CD8 SP T cells. Hence hypomethylation of the CD8 genes in DN T cells was interpreted to mean that DN T cells were derived from mature CD8 T cells. It is now known, however, that some DP thymocytes downregulate CD4 and CD8 to develop into bona fide DN T cells.25 The best known example is that of double negative natural killer T cells26 (DN NKT cells). In addition, another subpopulation of DP thymocytes has been shown to develop into DN T cells that emigrate to the gut epithelium to become intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL).27 Thus, hypomethylation of the CD8 gene in lpr DN T cells does not definitely mean they are progeny of peripheral CD8 T cells as they could simply be descendants of nDN T cells that have passed through a DP stage before downregulating their coreceptors and developing into mature nDN T cells in the thymus. Alternatively, but not mutually exclusive, misselected CD8 T cells have been shown to downregulate their coreceptors due to their failure to coengage MHC class I molecules, become DN T cells that subsequently upregulate Fas and FasL and die by Fas-mediated apoptosis.28 The second major observation used to support the traditional model was the finding that β2m-deficient lpr mice have decreased DN T cell lymphoproliferation.29, 30 Since β2m-deficient mice lack peripheral CD8 T cells, their reduced lymphoproliferation was considered secondary to that of CD8 T cells. The possibility that DN T cells represent a unique sub-lineage whose positive selection is mediated by non-classical β2m-dependent MHC molecules, however, has not been ruled out and it remains a valid possibility.

One of the most cited arguments in support of the idea that lpr DN T cells were derived from mature T cells that failed to undergo apoptosis is centred on their expression of B220. As mentioned above, B220, which is the B cell isoform of CD4522, is highly expressed on lpr DN T cells. In a study by Renno et al.31 it was found that WT CD4 T cells stimulated with the staphylococcal enterotoxin toxin B (SEB) superantigen expressed B220 on their cell surface before undergoing apoptosis.31 Correlatively, the authors considered expression of B220 by lpr DN T cells as evidence that they represent activated CD4 T cells31, 32 that failed to undergo apoptosis and accumulate after “presumed downregulation of their coreceptor.”31 There is no direct and reproducible evidence, however, that CD4 or CD8 T cells from lpr or gld mice could become B220+ DN T cells due to their failure to undergo apoptosis. In fact, the notion that CD4 or CD8 T cells from lpr or gld mice are resistant to AICD is inconsistent with studies24, 33 showing that in vivo deletion of superantigen-activated CD4 and CD8 T cells is Fas-independent. In numerous attempts to generate DN T cells by repeated in vitro CD3/CD28 activation of lpr CD4 or CD8 T cells, we failed, although we and others successfully generate DN T cells from Fas-sufficient TCR transgenic and polyclonal CD4 T cells using repeated in vitro CD3 stimulation (ref34 and unpublished data by Hamad et al.) and in mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR),35 respectively. Further challenges to the traditional view are provided by accumulating evidence that lpr DN T cells display unique properties that qualitatively distinguish them from CD4 and CD8 T cells (summarized in Table 1) and that they possess immunoregulatory functions.18, 19

Table 1.

Key distinguishing markers of DN T cell and single positive (CD4 and CD8) αβ T cells

| Characteristics | DN | SP | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | Anergic to TCR stimulation | Response to TCR Stimulation | Ref.55 |

| CD2 expression | Negative to low | high | Ref.25, 56 |

| CD45 | B220 isoform | T cell CD45 | Ref.57 |

| Fyn | Required for proliferation of DN T cells | Not required for proliferation of SP T cells | Ref.58 |

| Eomes | Overexpressed and essential for development or maintenance of DN T cells | Normal level and not required for lpr CD4 and CD8 T cell development or maintenance | Ref.59 |

| P2X7R | Defective expression and signalling | Normal | Ref.60 |

| Ion channels | Abundance number of type I K+ channels | CD4 T cells express small numbers of type 1 K+ channel whereas CD8+ T cells express low level of I and n K+ channels | Ref.61 |

Impaired sequestration of intraepithelial DN T cells: A new model to explain lpr DN T cell lymphoproliferation

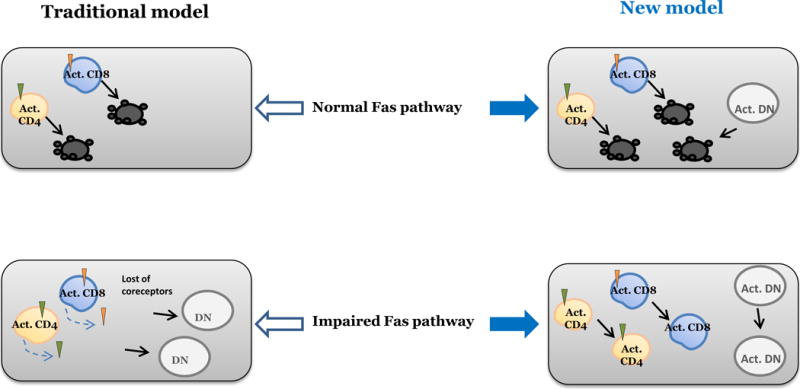

In light of the aforementioned caveats with the traditional model, we directly compared the transcript profiles of DN T cells and SP (mixed CD4 and CD8) T cells isolated from the same mutant mice. The results revealed significant qualitative differences between the two subpopulations that could not simply be explained by differences in activation states. lpr DN T cells expressed genes that are expressed by normal intestinal epithelial cells but not by conventional T cells (for details see ref.24). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that DN T cells in the gut epithelium shared several unique characteristics with lpr DN T cells, including the surface expression of B220 and CD5 and the lack of surface CD2. DN T cells in gut epithelium of both WT and mutant mice shared the same properties of expressing B220 and CD5 and lack of surface CD2. These similarities raised the intriguing possibility that intraepithelia DN T cells and lpr DN T cells share a common ontogeny. Furthermore, intraepithelial DN T cells are spontaneously proliferating and dying at very high rates in both WT and mutant mice by Fas-independent mechanism.24 On the other hand, consistent with their rarity,24, 36 the few nDN T cells found in periphery of WT mice were not proliferating but rapidly dying by Fas-mediated mechanism. Likewise, lpr DN T cells found in the periphery of mutant mice were not proliferating, but their apoptosis rate was significantly less than that of nDN T cells found in the periphery of WT mice.24, 36 Taken together, these data show the Fas death pathway plays an active role in peripheral deletion of nDN T cells. Significance and efficiency of this process is revealed by a quick increase in the frequency of nDN T cells when WT mice were treated with FasL-neutralizing mAb that was followed by their rapid clearance once the treatment was terminated.15 Based on this evidence, we developed a new model to explain how impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis leads to DN T cell lymphoaccumulation (depicted in Fig. 2). According to this model, Fas-mediated apoptosis is required for clearance of naturally occurring DN T cells and that impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis does not play a role in their generation, but rather is responsible for the elimination of pre-existing DN T cells. This model is fundamentally different from the traditional model which implicates impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis in the generation of lpr DN T cells as byproducts of activated CD4 or CD8 T cells that fail to undergo AICD.

Figure 2. Pros and cons of the traditional and newly proposed models.

According to the traditional model, death of chronically activated CD4 (Act. CD4) or CD8 (Act. CD8) T cells by Fas-mediated apoptosis accounts for the paucity of DN T cells in secondary lymphoid organs of WT mice and that loss-of-function mutations in the Fas pathway prevent death of activated CD4 and CD8 T cells that subsequently downregulate their coreceptors and persist as DN T cells. In contrast, our newly proposed model suggests DN T cells represent an independent subset that is normally rare in the secondary lymphoid organs because they are actively removed by Fas-mediated apoptosis, but gradually accumulate in these organs when the Fas death pathway is impaired. The new model also accounts for the exponential expansion of CD4 and CD8 T cells in mutant mice due to their persistence as such without coreceptor downregulation in mutant mice.

An important question provoked by the new model is: if lpr DN T cells were not derived from CD4 or CD8 T cells, what are their source(s)? There is increasing evidence that DN T cells generated in the thymus migrate and populate the gut epithelium. nDN T cells are also found in other non-lymphoid organs including the kidney37,38 and genital tract39 of mice. It is therefore plausible that Fas-mediated apoptosis actively removes DN T cells that erroneously stray into secondary lymphoid organs and that failure of this process leads to graduall accumulation of DN T cells in these organs. We also do not exclude the possibility that peripheral lymphoid organs serve as a dump ground where obsolete intraepithelial DN T cells are expelled and subsequently removed by Fas-mediated apoptosis. In both cases, naturally occurring nDN T cells are physiologically sequestered in the gut epithelium and perhaps other non-lymphoid organs such as the kidney, a mechanism that is enforced by Fas-mediated apoptosis. This model incorporates recent advances and offers alternative explanations for the original observations underlying the traditional model. Definitive confirmation of this new model obviously requires new experimentation and testing of its predictions. Confronting these questions could lead to new insights that explain the basis of DN T cell lymphoproliferation and uncover a novel physiological function for the Fas pathway.36

Normal (nDN) T cells and the long wait to emerge from under the shadow of lpr DN T cells

Besides in lpr and gld mice and TCR transgenic mice (for excellent review of immunoregulatory function of DN T cells, see ref.40, 41), DN T cells are increasingly investigated in WT mice. In addition, they are also being investigated in healthy humans and in certain disease conditions. As indicated above, nDN T cells are rare in secondary lymphoid organs, but abundant at least in certain non-lymphoid tissues. These include intestinal epithelium where nDN T cells comprise a substantial constituent of the αβ T cells.36 nDN T cells are also reported to predominate (70–90% of αβ T cells) in the female mouse genital tract.39 Presence of nDN T cells in the human female genital tract has not been directly examined, but clues for their presence is indicated by a significant and brief systemic expansion of DN T cells in a female patient with toxic shock syndrome, a disease that is usually associated with exposure to the toxic shock superantigen toxin (TSST) through vaginal mucosa.42 In addition, nDN T cells are reported to be an important source of infectious virus in HIV patients.43, 44 DN T cells also comprise a high percentage (20–25%) of αβ T cells in kidneys of mice37, 38 and in humans (Martina et al. unpublished results). By analogy, it is likely that nDN T cells are enriched in other non-lymphoid organs. A recently developed protocol for efficient isolation of DN T cells45 by our group is expected to facilitate isolation and analysis of nDN T cells from non-lymphoid tissues of both mice and humans.46, 47

Functional analysis of nDN T cells, however, is still seriously lagging behind that of conventional and unique lymphocytes as they are inadvertently and sometimes intentionally excluded from in vivo immunological analysis. Nonetheless, nDN T cells are emerging as major producers of IL-17 in response to infections and in autoimmune diseases such as lupus. In WT mice, nDN T cells are reported to be major responders to infection with the intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis48 where nDN T cells accumulated in infected lungs and released large amounts of IL-17. nDN T cells are also reported to accumulate rapidly in peritoneal cavities of mice infected with Listeria monocytogenes, where they produce IFN-γ and TNFα, in addition to IL-17.49 In lupus patients, the frequency of IL-17-producing nDN T cells is elevated in peripheral blood.50, 51 Regulatory roles of both lpr18, 19 and nDN T cells have been also reported in different settings, including in transplantation (reviewed in ref.40, 41) and in patients with mycosis fungoides (MF), a subgroup of epidermotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma52. In adult T-cell leukemia (ATL), a mature T-cell malignancy caused by human T lymphotropic virus type-I (HTLV-I), there were patients whose ATL cells are predominantly DN T cells53. In addition, Melan A and gp100 specific DN T cells have been described in cancer patients.46, 54 Thus, nDN T cells, similar to CD4 T cells, may be divided into functional subsets. However, as of yet there are no bona fide markers that distinguish functionally among DN T cells. Successful identification of such markers will play a significant role in promoting interest in nDN T cells.

Concluding remarks

Although the presence of nDN T cells in WT mice and humans is not in dispute, understanding their pathophysiologic function(s) is severely lagging behind that of the other immune cell types. Reaching this goal is beset by misperceptions as well as technical challenges. Misperceptions are generally fuelled by the tight association of DN T cells with the lpr phenotype and the prevailing view that they are abnormal T cells. We hope the newly proposed model will help in demystifying DN T cells. A major technical challenge impeding investigation of nDN T cell is the absence of specific markers necessary for conducting loss- and gain-of-function on DN T cells to reveal their pathophysiologic significance. More importantly, fundamental information including the MHC restricting element(s) regulating thymic development and antigen recognition by nDN T cells, physiological stimuli that trigger activation and types cytokine produced by DN T cells are lacking. Tackling these issues is critical for generating interest in nDN T cells and bringing them to main stream immunology.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant MPI R21 (to HR and ARAH). We thank Pamela Talalay and Norma Stocker for critical reading and editing of the manuscript

References

- 1.Trowell OA. Some properties of lymphocytes in vivo and in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1958;73:105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb40794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain RN. Special regulatory T-cell review: A rose by any other name: from suppressor T cells to Tregs, approbation to unbridled enthusiasm. Immunology. 2008;123:20–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy ED, Roths JB. A single gene model for massive lymphoproliferation with immune complex dsiease in new mouse strain MRL; Proceedings of the 16th International Congress in Hematology Excerpta Medica; Amsterdam. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roths JB, Murphy ED, Eicher EM. A new mutation, gld, that produces lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity in C3H/HeJ mice. J Exp Med. 1984;159:1–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morse H, Davidson W, Yetter R, Murphy E, Roths J, Coffman R. Abnormalities induced by the mutant gene lpr: expansion of a unique lymphocytes subset. J Immunol. 1982;129:2612–2615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson W, Dumont F, Bedigian H, Fowlkes B, Morse H. Phenotypic, functional and molecular genetic comparisons of the abnormal lymphpoid cells of C3H-lpr and C3h-gld/gld mice. J Immunol. 1986;136:4075–4084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sneller MC, Straus SE, Jaffe ES, Jaffe JS, Fleisher TA, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. A novel lymphoproliferative/autoimmune syndrome resembling murine lpr/gld disease. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:334–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI115867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer G, Rosenberg F, Straus S, Dale L, Middelton L, A L, et al. Dominant interfering Fas gene mutations impair apoptosis in a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Cell. 1995;81:1935–1946. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Brannan C, Copeland N, Jenkins N, Nagata S. Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defects in Fas antigen that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1992;356:314–317. doi: 10.1038/356314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grayson JM, Weant AE, Holbrook BC, Hildeman D. Role of Bim in regulating CD8+ T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Virol. 2006;80:8627–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00855-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–7. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark LB, Appleby MW, Brunkow ME, Wilkinson JE, Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F. Cellular and molecular characterization of the scurfy mouse mutant. J Immunol. 1999;162:2546–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chervonsky AV, Wang Y, Wong FS, Visintin I, Flavell RA, Janeway CA, Jr, et al. The role of Fas in autoimmune diabetes. Cell. 1997;89:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamood AS, Guler ML, Xiao Z, Zheng D, Hess A, Wang Y, et al. Protection from autoimmune diabetes and T-cell lymphoproliferation induced by FasL mutation are differentially regulated and can be uncoupled pharmacologically. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:97–106. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dittel BN. Evidence that Fas and FasL contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2000;48:381–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldner H, Sobel RA, Howard E, Kuchroo VK. Fas- and FasL-deficient mice are resistant to induction of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1997;159:3100–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamad AR, Mohamood AS, Trujillo CJ, Huang CT, Yuan E, Schneck JP. B220+ double-negative T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation by a Fas-independent mechanism that involves inhibition of IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2003;171:2421–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford MS, Young KJ, Zhang Z, Ohashi PS, Zhang L. The immune regulatory function of lymphoproliferative double negative T cells in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;196:261–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgerton C, Crispin JC, Moratz CM, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Simovic M, et al. IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells mediate accelerated ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury in autoimmunity-prone mice. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohamood AS, Trujillo CJ, Zheng D, Jie C, Martinez Murillo F, Schneck JP, et al. Gld mutation of Fas ligand increases the frequency and up-regulates cell survival genes in CD25+CD4+ TR cells. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1265–1277. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen P, Eisenberg R. Lpr and gld: Single gene models of systemic autoimmunity and lymphoproliferative disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonehara S, Ishii A, Yonehara M. A cell-killing monoclonal antibody (anti-Fas) to a cell surface antigen co-downregulated with the receptor of tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1747–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamood AS, Bargatze D, Xiao Z, Jie C, Yagita H, Ruben D, et al. Fas-Mediated Apoptosis Regulates the Composition of Peripheral alphabeta T Cell Repertoire by Constitutively Purging Out Double Negative T Cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landolfi M, van Houten N, Russell L, Scollay R, Parnes J, Budd R. CD2−CD4−CD8− lymph node T lymphocytes in MRL lpr mice are derived from a CD2+CD4+CD8+ thymic precursor. J Immunol. 1993;151:1086–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:557–68. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leishman AJ, Gapin L, Capone M, Palmer E, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, et al. Precursors of functional MHC class I- or class II-restricted CD8alphaalpha(+) T cells are positively selected in the thymus by agonist self-peptides. Immunity. 2002;16:355–64. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pestano GA, Zhou Y, Trimble LA, Daley J, Weber GF, Cantor H. Inactivation of misselected CD8 T cells by CD8 gene methylation and cell death. Science. 1999;284:1187–91. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mixter PF, Russell JQ, Durie FH, Budd RC. Decreased CD4−CD8− TCR-alpha beta + cells in lpr/lpr mice lacking beta 2-microglobulin. J Immunol. 1995;154:2063–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giese T, Davidson WF. In CD8+ T cell-deficient lpr/lpr mice, CD4+B220+ and CD4+B220− T cells replace B220+ double-negative T cells as the predominant populations in enlarged lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1995;154:4986–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renno T, Attinger A, Rimoldi D, Hahne M, Tschopp J, MacDonald HR. Expression of B220 on activated T cell blasts precedes apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:540–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<540::AID-IMMU540>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell JH, Rush B, Weaver C, Wang R. Mature T cells of autoimmune lpr/lpr mice have a defect in antigen-stimulated suicide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4409–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hildeman DA, Zhu Y, Mitchell TC, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Kappler J, et al. Activated T cell death in vivo mediated by proapoptotic bcl-2 family member bim. Immunity. 2002;16:759–67. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamad AR, Sean OH, Lebowitz Michael S, Srikrishnan Ananth, Bieler Joan, Schneck Jonathan, et al. Potent T cell activation with dimeric peptide-major histocompatibility complex class II ligand: The role of CD4 coreceptor. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1633–1640. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D, Yang W, Degauque N, Tian Y, Mikita A, Zheng XX. New differentiation pathway for double-negative regulatory T cells that regulates the magnitude of immune responses. Blood. 2007;109:4071–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamad AR. Analysis of gene profile, steady state proliferation and apoptosis of double-negative T cells in the periphery and gut epithelium provides new insights into the biological functions of the Fas pathway. Immunol Res. 2010;47:134–42. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ascon DB, Ascon M, Satpute S, Lopez-Briones S, Racusen L, Colvin RB, et al. Normal mouse kidneys contain activated and CD3+CD4− CD8− double-negative T lymphocytes with a distinct TCR repertoire. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1400–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ascon DB, Lopez-Briones S, Liu M, Ascon M, Savransky V, Colvin RB, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of kidney-infiltrating lymphocytes in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2006;177:3380–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson M, Lycke N. A unique population of extrathymically derived alpha beta TCR+CD4−CD8− T cells with regulatory functions dominates the mouse female genital tract. J Immunol. 2003;170:1659–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juvet SC, Zhang L. Double negative regulatory T cells in transplantation and autoimmunity: recent progress and future directions. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:48–58. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Acquisto F, Crompton T. CD3(+)CD4(−)CD8(−) (double negative) T cells: Saviours or villains of the immune response? Biochem Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carulli G, Lagomarsini G, Azzara A, Testi R, Riccioni R, Petrini M. Expansion of TcRalphabeta+CD3+CD4−CD8− (CD4/CD8 double-negative) T lymphocytes in a case of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome. Acta Haematol. 2004;111:163–7. doi: 10.1159/000076526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sundaravaradan V, Mir KD, Sodora DL. Double-negative T cells during HIV/SIV infections: potential pinch hitters in the T-cell lineup. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:164–71. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283504a66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marodon G, Warren D, Filomio MC, Posnett DN. Productive infection of double-negative T cells with HIV in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11958–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martina MN, Bandapalle S, Rabb H, Hamad AR. Isolation of Double Negative alphabeta T Cells from the Kidney. J Vis Exp. 2014;87 doi: 10.3791/51192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer K, Voelkl S, Heymann J, Przybylski GK, Mondal K, Laumer M, et al. Isolation and characterization of human antigen-specific TCR alpha beta+ CD4(−)CD8− double-negative regulatory T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2828–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voelkl S, Gary R, Mackensen A. Characterization of the immunoregulatory function of human TCR-alphabeta+ CD4− CD8− double-negative T cells. Eur J Immunol. 41:739–48. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowley SC, Meierovics AI, Frelinger JA, Iwakura Y, Elkins KL. Lung CD4−CD8− double-negative T cells are prominent producers of IL-17A and IFN-gamma during primary respiratory murine infection with Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. J Immunol. 2010;184:5791–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riol-Blanco L, Lazarevic V, Awasthi A, Mitsdoerffer M, Wilson BS, Croxford A, et al. IL-23 receptor regulates unconventional IL-17-producing T cells that control bacterial infections. J Immunol. 2010;184:1710–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crispin JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, Cohen RA, Van Beek CA, Stillman IE, et al. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. J Immunol. 2008;181:8761–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z, Kyttaris VC, Tsokos GC. The role of IL-23/IL-17 axis in lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2009;183:3160–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodak E, David M, Maron L, Aviram A, Kaganovsky E, Feinmesser M. CD4/CD8 double-negative epidermotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: an immunohistochemical variant of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzushima H, Asou N, Hattori T, Takatsuki K. Adult T-cell leukemia derived from S100 beta positive double-negative (CD4− CD8−) T cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;13:257–62. doi: 10.3109/10428199409056289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voelkl S, Moore TV, Rehli M, Nishimura MI, Mackensen A, Fischer K. Characterization of MHC class-I restricted TCRalphabeta+ CD4− CD8− double negative T cells recognizing the gp100 antigen from a melanoma patient after gp100 vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:709–18. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davignon J, Cohen P, Eisnebrg R. Rapid T cell receptor modulation accompanies lack of in vitro mitogenic responsiveness of double negative Tcells to anti-CD3 monolconal antibody in MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol. 1988;141:1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shirai T, Abe M, Yagita H, Okumura K, Morse HC, 3rd, Davidson WF. The expanded populations of CD4−CD8− T cell receptor alpha/beta+ T cells associated with the lpr and gld mutations are CD2. J Immunol. 1990;144:3756–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamashita Y, Imai Y, Osawa T. Alpha 2,3-linked sialic acids are more abundant in CD45 antigens and leukosialins of abnormal T cells of lpr mice than in those of normal T cells. J Biochem. 1989;106:961–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balomenos D, Rumold R, Theofilopoulos AN. The proliferative in vivo activities of lpr double-negative T cells and the primary role of p59fyn in their activation and expansion. J Immunol. 1997;159:2265–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kinjyo I, Gordon SM, Intlekofer AM, Dowdell K, Mooney EC, Caricchio R, et al. Cutting edge: Lymphoproliferation caused by Fas deficiency is dependent on the transcription factor eomesodermin. J Immunol. 2010;185:7151–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Gall SM, Legrand J, Benbijja M, Safya H, Benihoud K, Kanellopoulos JM, et al. Loss of P2X7 receptor plasma membrane expression and function in pathogenic B220+ double-negative T lymphocytes of autoimmune MRL/lpr mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grissmer S, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Abundant expression of type l K+ channels. A marker for lymphoproliferative diseases? J Immunol. 1988;141:1137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]