Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) possess unique specificity for nerve terminals. They bind to the presynaptic membrane and then translocate intracellularly, where the light-chain endopeptidase cleaves the SNARE complex proteins, subverting the synaptic exocytosis responsible for acetylcholine release to the synaptic cleft. This inhibits acetylcholine binding to its receptor, causing paralysis. Binding, an obligate event for cell intoxication, is believed to occur through the heavy-chain C-terminal (HC) domain. It is followed by toxin translocation and entry into the cell cytoplasm, which is thought to be mediated by the heavy-chain N-terminal (HN) domain. Submolecular mapping analysis by using synthetic peptides spanning BoNT serotype A (BoNT/A) and mouse brain synaptosomes (SNPs) and protective antibodies against toxin from mice and cervical dystonia patients undergoing BoNT/A treatment revealed that not only regions of the HC domain but also regions of the HN domain are involved in the toxin binding process. Based on these findings, we expressed a peptide corresponding to the BoNT/A region comprising HN domain residues 729 to 845 (HN729–845). HN729–845 bound directly to mouse brain SNPs and substantially inhibited BoNT/A binding to SNPs. The binding involved gangliosides GT1b and GD1a and a few membrane lipids. The peptide bound to human or mouse neuroblastoma cells within 1 min. Peptide HN729–845 protected mice completely against a lethal BoNT/A dose (1.05 times the 100% lethal dose). This protective activity was obtained at a dose comparable to that of the peptide from positions 967 to 1296 in the HC domain. These findings strongly indicate that HN729–845 and, by extension, the HN domain are fully programmed and equipped to bind to neuronal cells and in the free state can even inhibit the binding of the toxin.

INTRODUCTION

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the most potent toxins and are ranked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as bioterrorism threats with the six highest-risk class A agents (1). The potency of the toxin is due to its outstanding specificity to nerve terminals and selective enzymatic activity, resulting in the cleavage of SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complex proteins. The cleavage of SNARE proteins inhibits the fusion of synaptic vesicles (containing the neurotransmitter) to the plasma membrane, thereby blocking neurotransmitter release and causing paralysis (2, 3).

Unraveling the features of the mode of action of BoNTs has permitted numerous applications of the toxins in many therapeutic, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic applications (4–7). However, understanding of the full biochemical mechanism of its action still remains to be elucidated.

BoNTs, produced by Gram-positive, obligate anaerobic Clostridium botulinum bacteria, are classified into eight different serotypes (A through H) (8–10). BoNTs are expressed as a single polypeptide chain (∼150 kDa) which is posttranslationally cleaved to produce an N-terminal light (L) chain of ∼50 kDa, which is a Zn2+ metalloprotease, and a heavy (H) chain of ∼100 kDa. The L and H chains are linked together by a disulfide bond and other noncovalent interactions to form the active toxin. The H chain is further functionally divided into two seemingly independent domains: the N-terminal or translocation (HN) domain and the C-terminal receptor-binding (HC) domain (11).

The entry of BoNT into neurons and its resultant toxicity are exhibited in a systematic manner, accomplished by a superb molecular partnership between the H and L chains. It is believed that an intricate mechanism involving various low- and high-affinity interactions is involved in intoxication of the cell (12). The difference in pH and redox potential across the endosomes is believed to induce conformational changes in the H chain, which subsequently forms a chaperone and channels the L chain into the cytosol. Once the L chain is translocated, it is subsequently released by disulfide bond reduction, followed by its refolding in the neutral cytosol, where it cleaves the SNARE substrates (13).

The current understanding of toxin entry into the cell is that the HC domain binds to the neurons via dual host receptors (gangliosides and a neuronal coreceptor) (14) and the HN domain translocates the L-chain subunit into the cytoplasm. Coordination between the HC and HN domains is believed to be very important for efficient translocation of the L chain (15–18). However, very little is known about the HN domain function, but the HN domain is thought to be important for orienting the L chain and forming channels across the endosomal membrane (19). Our previous studies (20) using short (19-residue) overlapping peptides to map the synaptosome (SNP) binding regions on the H chain of BoNT/A showed that certain regions of the HN domain as well as the HC domain are capable of inhibiting BoNT binding to SNPs. Another study (21) reported that the L chain can be translocated efficiently by the HN domain alone in the absence of the HC domain. However, the precise role of the HN domain in membrane binding and insertion or channel formation is still unknown (22). The present work was carried out to further investigate the role of the HN domain in BoNT binding to the cell membrane and its entry into the cytosol. We have prepared a 117-residue segment comprising residues 729 to 845 of the HN domain (HN729–845) which contains sites that bind mouse brain SNPs (20) as well as sites that bind anti-BoNT serotype A (anti-BoNT/A) antibodies (Abs) of mouse (23) and human (24) origin (Fig. 1A and Table 1). We studied the binding of this construct to SNPs and membrane components and visualized its binding to mouse and human neuroblastoma cells, as well as assessed its protective ability against the whole toxin in vivo.

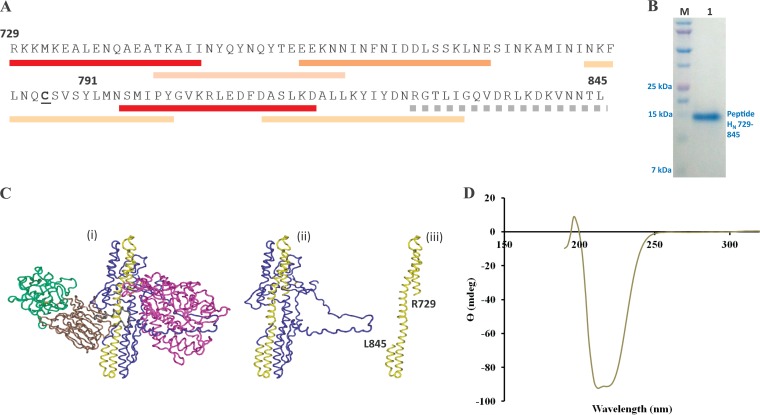

FIG 1.

Structural characterization of BoNT/A peptide HN729–845. (A) Primary structure of the recombinant peptide HN729–845 prepared in the present work. The 117-residue peptide with a hexahistidine tag at the C terminus has a molecular mass of 14,429.3 Da, and its isoelectric point is 8.01. Synaptosome-binding regions (marked underneath by red bars) and the regions recognized by protective antibodies (tan bars) (from Maruta et al. [20]) are marked (Table 1). Heavy bar colors indicate high activity, lighter bar colors indicate moderate activity, and dotted bars denote weak activity. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified peptide HN729–845 shows that a high yield of purified peptide (>96%) was obtained from the inclusion bodies, solubilized using 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium lauryl sarcosine. The expressed peptide was purified using IMAC. Lane M, Bio-Rad Precision Plus Protein Dual Xtra standard; lane 1, purified HN729–845. (C) Images showing the shape and 3-D location (in yellow) of the HN729–845 region within the 3-D structure of whole BoNT/A (i), the HN domain of BoNT/A only (ii), and the HN729–845 region by itself (iii). The 3-D structure of BoNT/A was determined by Lacy et al. (64). The figure is not intended to imply here that free HN729–845 retains the same 3-D shape presented; rather, it is given to show the shape that this segment has in the intact protein. (D) CD spectrometry analysis of purified HN729–845 shows that the isolated peptide retains an α-helical structure, as expected from its 3-D arrangement in the native BoNT/A.

TABLE 1.

BoNT/A regions on HN involved in toxin binding to mouse brain SNPs, mouse anti-BoNT/A Abs, or blocking Abs from cervical dystonia patientsa

| Peptide | Binding residue no. | Binding to: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | Mouse Abs | Cervical dystonia Abs | ||

| N21 | 729–747 | ++ | − | − |

| N22 | 743–761 | − | + | + |

| N23 | 757–775 | + | − | − |

| N24 | 771–789 | − | + | − |

| N25 | 785–803 | − | +++++ | +++ |

| N26 | 799–817 | +++ | − | − |

| N27 | 813–831 | − | +++ | − |

| N28 | 827–845 | − | +++ | − |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The animal experiments described in the current study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM; protocol number AN-3018) and were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (25).

Reagents.

Active BoNT/A was obtained from Metabiologics (Madison, WI) as a solution (0.25 mg/ml) in 0.15 M NaCl in 0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) containing 25% (vol/vol) glycerol and stored at −20°C. Enzymes were from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Bacterial strain BL21(DE3)pLysS, the pET 26b(+) vector, and Terrific Broth (TB) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and gangliosides GD1a and GT1b were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated.

Gene synthesis and cloning.

The BoNT/A heavy-chain gene (Okra strain) was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). A segment of the HN region from residues 729 to 845 was amplified from the BoNT/A heavy-chain gene using primers 5′-GGC CGG ATC CGA TGC GTA AAA AAA TGA AAG AAG C-3′ and 5′-CCT TAG CGG CCG CAA GTG TAT TAT TAA CTT TAT CTT TTA AAC G-3′. The amplicon was digested using BamHI/NotI enzymes and cloned into the pET 26b(+) vector using T4 DNA ligase. The resultant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells, and the positive colonies were confirmed by sequencing.

Peptide expression and purification.

A HN729–845-positive clone was grown in TB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 1% (wt/vol) glucose until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6. The culture was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). The culture was pelleted and resuspended in sonication buffer (150 mM PBS [pH 7.2], 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). Cells were lysed by sonication (3 min; a 5-s cycle with a 2-s break at 50 A), and the soluble proteins were separated. The pellet, containing inclusion bodies, was resuspended in sonication buffer, containing 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium lauryl sarcosine (Amresco, Solon, OH), and stirred overnight at 4°C. The lysate was centrifuged at 8,793 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. HN729–845 was purified from the supernatant by passing it through an immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) column. The peptide was eluted with 250 mM imidazole in 150 mM PBS, followed by two buffer exchanges in sterile PBS using Amicon Ultra-15 columns (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The peptide was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Secondary structure analysis of HN729–845 CD spectrometry.

Circular dichroism (CD) experiments were performed using a J-810 CD spectrometer (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) with 75 μM HN729–845. The far-UV spectra (350 nm to 180 nm) of HN729–845 were recorded by using a bandwidth of 2 nm at 25°C. The spectrum was the average of 4 scans at a scan rate of 100 nm/min. The spectrum was corrected for the blank and smoothed using a Fast Fourier transform filter (Jasco Software, Tokyo, Japan).

Labeling of BoNT/A and HN729–845 peptide for binding studies.

Isolation of SNPs from mouse brain was done as originally described (26) with minor modifications (27). Active BoNT/A (10 μg) and HN729–845 (50 μg) were labeled with 125I (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) by the chloramine T method (28). Unbound 125I was removed from 125I-labeled BoNT/A or peptide by passing the reaction mix through a Sephadex G-25 fine column (in Ringer's buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Tris, and 0.5% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin [BSA] [pH 7.0]). Various fractions (200 μl) were collected, and radioactivity was measured on an automatic gamma counter (1277 Gammamaster; LKB-Wallac, Turku, Finland). Fractions containing 125I-labeled product were pooled. 125I-labeled BoNT/A and 125I-labeled HN729–845 peptide were stored at 4°C and used within 2 weeks.

Binding analysis of BoNT/A and HN729–845 peptide to mouse brain SNPs.

Binding of BoNT/A or HN729–845 was analyzed by adding a fixed amount of 125I-labeled toxin, test peptide, or a control peptide (50,000 cpm) to different concentrations of SNPs (100 to 700 ng/ml) in 100 μl of Ringer's buffer in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. The suspension was mixed gently for 20 min at 37°C, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 3 min at room temperature. The supernatant was carefully aspirated, and the SNPs were washed with Ringer's buffer. The bottoms of the microcentrifuge tube were cut out and placed into clean borosilicate disposable glass tubes (VWR, Radnor, PA), and the bound radioactivity was measured in an automatic gamma counter (1277 Gammamaster; LKB-Wallac, Turku, Finland). The binding was analyzed in triplicate for each synaptosome concentration, and the data were verified by carrying out three independent analyses. The binding results were corrected for nonspecific binding by subtracting the binding values for the controls, and the standard deviation (SD) was calculated.

In vitro inhibition of BoNT/A binding by peptide HN729–845.

The ability of HN729–845 to inhibit the binding of 125I-labeled BoNT/A to SNPs was determined. Different concentrations of unlabeled the HN domain peptide (3.4 pM to 88.8 pM) in Ringer's buffer were incubated with a fixed amount (300 ng) of SNPs in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube for 1 h at 37°C. 125I-labeled BoNT/A (50,000 cpm) was added to the tubes (final reaction mixture volume, 100 μl), and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for an additional 20 min. SNPs were collected and washed, and bound radioactivity was measured as described previously. The percent inhibition of 125I-labeled BoNT/A binding relative to the level of binding for the uninhibited controls was calculated. Inhibition analyses were carried out in triplicate for each concentration of HN729–845 peptide, and the data were verified by repeating the analysis three times.

Confocal analysis of peptide HN729–845 interaction with neuroblastoma cells.

Murine Neuro 2a neuroblastoma cells were seeded in 4-well chamber slides at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in DMEM–F-12 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum. On the following day, the cells were washed with PBS and treated with 16.67 μM HN729–845 for different time periods. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and subsequently blocked with PBS containing 1% (wt/vol) BSA and 5% (vol/vol) goat serum. The cells were incubated with a 1/500 (vol/vol) dilution of mouse anti-His monoclonal antibody (MAb; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 1 h. The cells were washed three times and then stained with 1/200 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 h at room temperature. The nucleus was counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dilactate (DAPI), for 10 min. After the cells were washed twice with PBS, the coverslips were mounted using PermaFluor aqueous mounting medium (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Another set of experiments was carried out to analyze the binding of HN729–845 to cells of the human BE(2)-M17 neuroblastoma cell line using conditions similar to those used for Neuro 2a cells. Five independent analyses were carried out to confirm the binding of HN729–845 to neuronal cells.

Subcellular localization of HN729–845 peptide and analysis of its interaction with membrane components.

The localization of HN729–845 was studied using a plasma membrane marker, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA). Briefly, the cells were incubated with 16.67 μM HN729–845 along with 5 μg/ml rhodamine-labeled WGA (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h. Cells were washed, fixed, and labeled as described above. The study was repeated three times, and images were taken by sequentially exciting the fluorophores using individual excitation and emission filters.

Triton X-114 phase partitioning assay.

Localization of HN729–845 on cells was confirmed by a Triton X-114 phase partitioning assay using synaptosomes. Crude SNPs (50 μg) were treated with 666.6 pM HN729–845 peptide in PBS for 15 min at 37°C. Synaptosomes were collected by centrifugation (20,000 × g for 3 min), and the supernatant was discarded. Synaptosomes were washed 5 times with PBS to remove any unbound peptide. A Triton X-114 phase partitioning assay was performed as described by Bordier (29), with minor modifications. Briefly, the SNPs were lysed by adding 200 μl of 2.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-114 in PBS containing protease inhibitor and incubating for 30 min on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was carefully layered on a 6% sucrose cushion (50 μl) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The aqueous and detergent phases were collected by centrifuging the sample at 4,000 × g, and protein was precipitated using acetone. The samples were suspended in equal volumes of SDS-PAGE buffer, and HN729–845 localization was analyzed by subjecting them to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. Partitioning assays were independently repeated three times to confirm the results.

HN729–845 binding to membrane lipids.

Nitrocellulose membrane strips coated with various membrane lipids were purchased from Echelon Biosciences Inc., Salt Lake City, UT. The membrane lipid array was incubated with HN729–845 (1 μg/ml) for 1 h, and the assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. HN729–845 binding to membrane lipids was probed with a 1/2,000 (vol/vol) dilution of mouse anti-His MAb, followed by detection of the complex with a 1/2,000 (vol/vol) dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse Fc-specific antibody. After washing, the reaction was developed with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate.

Binding of HN729–845 to GD1a.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was carried out in triplicate by coating microtiter wells with 100 μl of HN729–845 or BoNT/A (6.67 nM). The plate was incubated overnight and then blocked for 1 h at 37°C with 3% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS. After the plate was washed with PBS, 100-μl aliquots containing different amounts of GD1a (209.0, 104.5, 52.3, 26.1, and 0 nM) in 1% (wt/vol) BSA–PBS were added and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The plate was then washed 5 times with PBS, and bound GD1a was detected by adding a 1/4,000 dilution (vol/vol) of anti-GD1a antibody (1B7) in 1% (wt/vol) BSA–PBS. After incubation, the plate was washed 5 times with PBS and the reaction mixture was probed with a 1/2,000 (vol/vol) dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse Fc-specific antibody in 1% (wt/vol) BSA–PBS. The plate was washed 5 times, and the color reaction was developed using TMB substrate. After 10 min, the reaction was quenched with 10% (vol/vol) HCl and the plate was read at 450 nm in a plate reader.

Inhibition assays were carried out (in triplicate) with both the GD1a and GT1b gangliosides. Different doses of the GD1a (10.7 nM to 418 nM) and GT1b (9.6 nM to 376 nM) gangliosides were mixed with 125I-labeled HN domain peptide (50,000 cpm) in Ringer's buffer (reaction mixture volume, 97 μl), and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. SNPs (3 μl) were then added to the mixture and the inhibition assay carried out as described previously. The analysis was repeated three times to confirm the results of the study.

To confirm the binding of HN729–845 with gangliosides, another set of experiments was carried out by incubating the cells (Neuro 2a, CHO-K1, and HEK-293T cells) with GD1a (100 μg/ml) in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were washed three times with PBS and treated with HN729–845 for 10 min. Following the treatment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, probed with mouse anti-His MAb, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG and DAPI, as detailed above. The influence of exogenous GD1a loading to the cell surface was confirmed by repeating the study three times. Images were taken at room temperature by sequentially exciting the fluorophores. Images were processed in the Adobe Photoshop program and then moved to the Adobe Illustrator program with the application of linear corrections.

Protective activity of peptide HN729–845 in vivo.

The 100% lethal doses (LD100s) of the active BoNT/A and BoNT/B preparations were determined in outbred (ICR) mice by injecting different doses of the toxin (5 mice per dose) intravenously in the tail. The mice were observed 3 times a day for 6 days. The lowest dose at which no mice survived was defined as the LD100.

The protective efficacy of the peptide against BoNT/A was then investigated by mouse protection assays (MPAs). Active BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) and BoNT/B (1.05× LD100) were mixed with various doses of HN729–845 (1 μg, 5 μg, 25 μg, and 50 μg for BoNT/A; 25 μg and 50 μg for BoNT/B) immediately before injection. The mixtures were then injected intravenously (5 mice per dose) into the tail. A control group received only 1.05× LD100 of active BoNT/A or BoNT/B without any peptide. A similar peptide (HN domain residues 721 to 859 [HN721–859]) of BoNT/B with a helical structure identical to that of BoNT/A HN729–845 was used as a control in MPA assays against BoNT/A.

In order to relate the protective efficacy of HN729–845 to the HC domain, MPA assays were carried out in parallel using the HC domain from residues 967 to 1296 (HC967–1296). Various doses of HC967–1296 (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 μg) were mixed with BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) immediately before injection and administered intravenously (5 mice per dose) into the tail. Mice were observed 3 times a day for 6 days, and the times of their death were recorded. At the end of the 6th day, protective efficacy was measured by determination of the number of mice (if any) that survived the toxin challenge.

The protective efficacy of HN729–845 was further assessed by administering increasing lethal doses (1.5× LD100, 3× LD100, and 5× LD100) of the toxin premixed with 50 μg of HN729–845 intravenously in the mouse tail. Five mice per group were studied per dose, and a control group that received similar doses of BoNT/A only (without HN729–845) was also studied. The mice were monitored for 6 days, and the level of protection in a given group was assayed by determination of the number of surviving mice. The in vivo assays were repeated three times to confirm the protective efficacy of HN729–845.

RESULTS

Expression, purification, and characterization of peptide HN729–845.

Expression of the synthetic cDNA construct in the BL21 strain of E. coli produced a major fraction of the His-tagged peptide in the inclusion bodies. The peptide was solubilized using 0.5% sodium lauryl sarcosine and isolated by IMAC. The expressed peptide product was over 96% pure (Fig. 1B) and retained much of its secondary structure (Fig. 1C) and/or folding (>65% alpha-helical structure) in the native BoNT/A HN domain after purification, as verified by CD spectroscopy analyses (Fig. 1D).

Binding of peptide HN729–845 to synaptosomes.

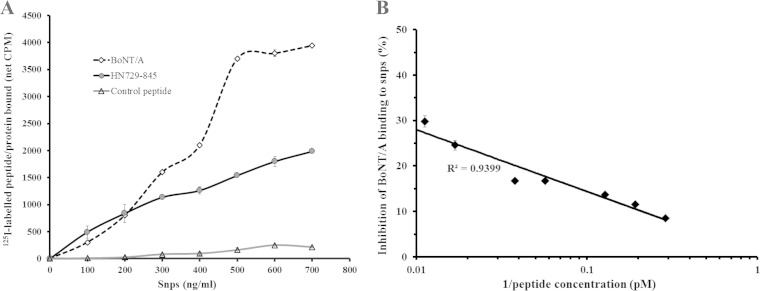

Peptide HN729–845 was capable of binding directly to mouse brain SNPs. Figure 2A shows the binding of 125I-labeled peptide to increasing amounts of SNPs. The peptide was also able to inhibit the binding of BoNT/A to SNPs (Fig. 2B). A reciprocal plot of different peptide concentrations relative to a fixed amount of labeled BoNT/A showed that the peptide gave a maximum inhibition of 30% of 125I-labeled BoNT/A (50,000 cpm) binding to SNPs (Fig. 2B). This was expected, since there is at least one other region in the toxin (within the HC domain) which also participates in cell binding.

FIG 2.

Peptide HN729–845 is capable of independently binding to the synaptosomes in the absence of the HC domain. (A) Binding of peptide HN729–845 to synaptosomes was determined by incubating fixed amounts of 125I-labeled peptide (50,000 cpm) with increasing amounts of SNPs (100 ng to 700 ng/ml). The graph shows an increase in the binding of 125I-labeled HN729–845 and 125I-labeled BoNT/A with an increase in the SNP concentration. A control 125I-labeled peptide was used as a negative control. Results show the mean ± SD from the analysis of each concentration in triplicate from an independent data set (n = 3). (B) An inhibition assay was carried out to confirm the binding of HN729–845 to SNPs. Different amounts of unlabeled HN729–845 (3.4 pM to 88.8 pM) were incubated (1 h, 37°C) with a fixed amount (300 ng) of SNPs, followed by addition of 125I-labeled BoNT/A (50,000 cpm). The inhibition assay showed that HN729–845 is capable of inhibiting BoNT/A binding to SNPs by about 30%, thus confirming the binding of the peptide to SNPs (n = 3). Results show the mean ± SD from triplicate analyses from an independent experiment.

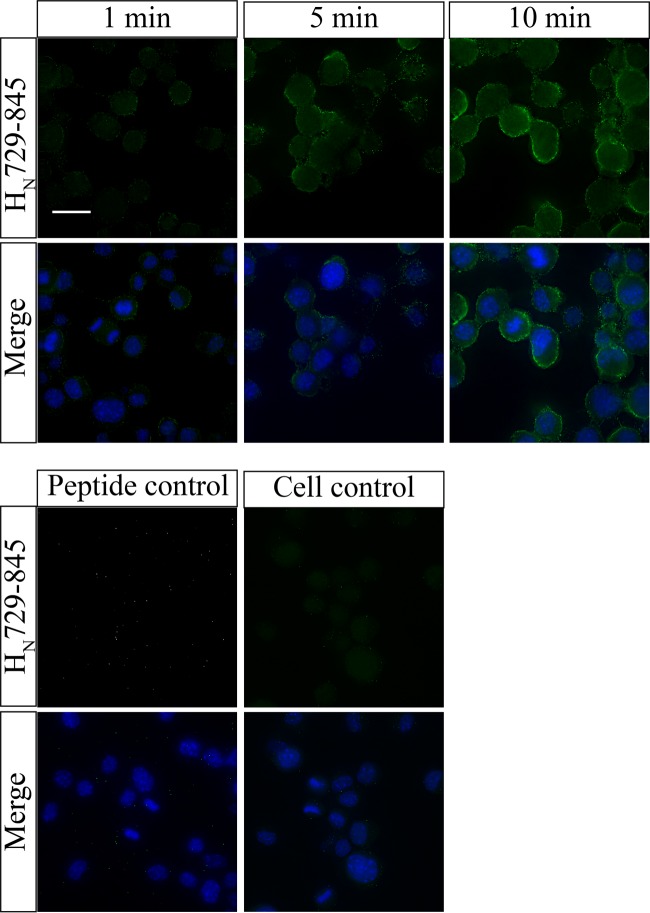

Confocal analysis of HN729–845 interaction to neuroblastoma cells.

Peptide HN729–845 was found to bind rapidly (within 1 min) to cells of mouse neuroblastoma cell line Neuro 2a (Fig. 3). With longer incubation periods (5 min and above), a uniform distribution of peptide on the cell surface was observed. The study was repeated with cells of a human neuroblastoma cell line, BE(2)-M17, and provided similar results (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

Peptide HN729–845 independently binds mouse Neuro 2a cells. Confocal analysis was carried out to study the interaction of peptide HN729–845 with mouse Neuro 2a cells. The cells were treated with peptide HN729–845 for 1, 5, or 10 min. (Top) Peptide interaction with the cell visualized by the green channel (Alexa Fluor 488) (first row) and an overlay image of the green and blue channels showing nuclear staining by DAPI (second row). Bar, 20 μm. (Bottom) Action of an unrelated peptide with a hexahistidine tag on Neuro 2a cells under conditions identical to those used for the assay whose results are presented in the top panels as a control (n = 5).

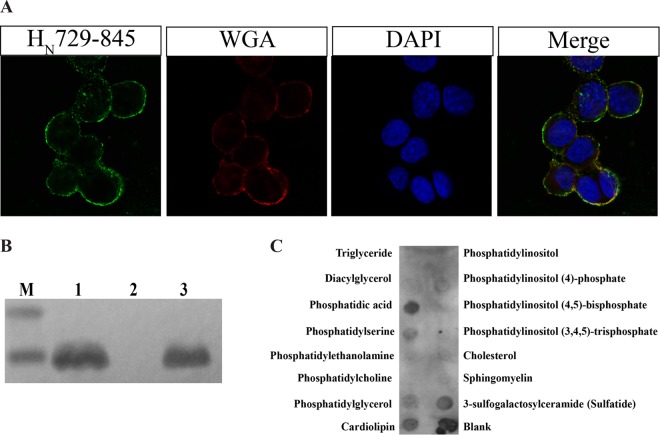

Subcellular localization of HN729–845.

Confocal analysis of HN729–845 with the plasma membrane marker WGA showed that the peptide resides at the membrane, even after an incubation of 1 h (Fig. 4A). To confirm this, a Triton X-114 phase partitioning assay was carried out to find the localization of HN729–845 in SNPs. Triton X-114 is a nonionic detergent that is homogeneous at 0°C in solution. When this solution is warmed to temperatures above 20°C, it results in turbidity, followed by phase separation into aqueous and detergent phases. Integral proteins partition into the detergent phase, whereas most peripheral proteins go into the aqueous phase (26). HN729–845 was found in the detergent phase (Fig. 4B), which shows its interaction with integral membrane proteins or membrane-anchoring lipids.

FIG 4.

HN729–845 binds to the cell surface and interacts with membrane lipids. (A) Binding of HN729–845 to the cell surface was evaluated by using rhodamine-labeled cell surface marker WGA, which binds to sialic acid and N-acetylglucosamine residues of membrane glycoproteins or glycolipids. The binding of HN729–845 to the cell surface (in green), rhodamine-labeled WGA staining of cells (red), DAPI staining of nuclei (blue), and a merged image of the green, red, and blue channels are shown. The study shows that peptide HN729–845 is localized on the membrane surface (n = 3). (B) A Triton X-114 phase partitioning assay was carried out to determine the binding of HN729–845 to the membrane. Synaptosomes were treated with the peptide, and then the synaptosomes were lysed using Triton X-114. The detergent and aqueous phases of the lysate were separated, and HN729–845 was detected using mouse anti-His antibody. Lane M, Bio-Rad Precision Plus Protein Dual Xtra standard; lane 1, total synaptosome lysate; lane 2, aqueous fraction; lane 3, detergent fraction (n = 3). (C) Membrane lipid analysis showing the interaction of HN729–845 with membrane lipids. Peptide HN729–845 bound strongly to phosphatidic acid, moderately to sulfatide and cardiolipin, and mildly to phosphatidylserine.

On the basis of the results from the Triton X-114 partitioning assay and the cell assays, the HN729–845 interaction with membrane lipids was analyzed by a lipid dot blot assay using membrane lipid strips. Peptide HN729–845 showed binding to membrane lipids, such as phosphatidic acid, sulfatide, and cardiolipin, which are ubiquitous constituents of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4C).

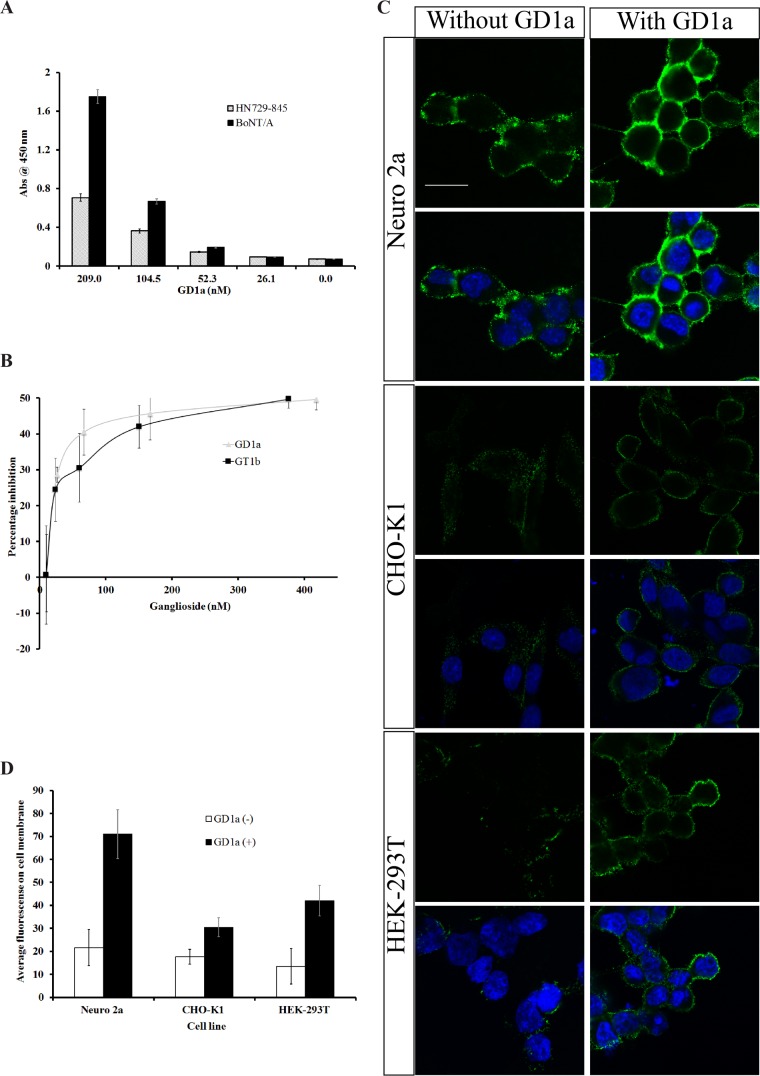

Interaction of HN729–845 with gangliosides.

Peptide HN729–845 showed the ability to bind to ganglioside GD1a. At equimolar coated peptide or toxin concentrations and different GD1a concentrations, the level of binding of HN729–845 to GD1a was less than that of BoNT/A (Fig. 5A). This was expected because a ganglioside binding region(s) is located in the HC domain. The specificity of the assay was confirmed by inhibiting HN729–845 binding to SNPs by ganglioside GD1a or GT1b. Figure 5B shows the inhibition of 125I-labeled peptide binding to SNPs by each of the two gangliosides. Ganglioside GD1a or GT1b inhibited peptide binding to SNPs by a maximum of 50%, indicating that binding to gangliosides makes a major contribution to the binding of this peptide to SNPs.

FIG 5.

HN729–845 binds to gangliosides GD1a and GT1b. (A) Binding of HN729–845 and BoNT/A to gangliosides at different concentrations of the ganglioside GD1a was evaluated by ELISA. Equimolar concentrations (6.66 nM) of peptide or BoNT/A were coated on the plate, and the amount of GD1a captured was detected using anti-GD1a antibody. The study was carried out in triplicate by capturing different concentrations of GD1a (209.0, 104.5, 52.3, 26.1, and 0 nM). BoNT/A showed a higher level of capture of GD1a than the peptide did. Experiments were repeated three times, and the mean values ± SDs from triplicate analyses are plotted. (B) Inhibition of the binding of 125I-labeled HN729–845 to SNPs was determined by incubating GD1a and GT1b with HN729–845. Different doses of ganglioside GT1b (9.6 nM to 376 nM) or GD1a (10.7 nM to 418 nM) were mixed with 125I-labeled HN729–845 (50,000 cpm), and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Synaptosomes were then added to the ganglioside-peptide mixture, and bound radioactivity was measured. Percent inhibition was estimated using an uninhibited control. The inhibition assay showed that both GD1a and GT1b inhibited the binding of HN729–845 to SNPs by up to 50% (n = 3). Results represent means ± SDs from triplicate analyses. (C) Neuro 2a, CHO-K1, and HEK-293T cells were treated with GD1a (100 μg/ml) for 1 h. After the excess free GD1a was washed away, the cells were incubated with HN729–845 for 10 min. The four images in the upper panel show the peptide interaction with the Neuro 2a cell, as visualized by the green channel (Alexa Fluor 488; top two images), and an overlay image of the green and blue channels showing nuclear staining by DAPI is shown (bottom two images). Bar, 20 μm. The four images in the middle and lower panels present the results of the same study with CHO-K1 and HEK-293T cells. The panels on the left show HN729–845 binding in the absence of GD1a, and those on the right show the HN729–845 cell interaction in the presence of GD1a. Identical conditions were used both in the presence and in the absence of GD1a. Addition of GD1a exogenously seemed to enhance the binding of HN729–845 to the cell surface (n = 3). (D) Representative fluorescence intensity profiles of cells (i) without exogeneously loaded GD1a and (ii) with exogeneously loaded GD1a were calculated using ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health). An increase in the intensity was found for cells with exogenously added GD1a in all three cell lines tested (Neuro 2a, CHO-K1, and HEK-293T) (n = 9, mean ± SD).

To verify the involvement of gangliosides in the binding of HN729–845 to the cell membrane, GD1a was exogenously loaded onto Neuro 2a cells. GD1a increased the binding of HN729–845 to the cell surface (Fig. 5C and D). These results were confirmed using CHO-K1 and HEK-293T cells (Fig. 5C), which lack the ability to synthesize endogenous GD1a. However, in the absence of GD1a, HN729–845 showed much lower levels of binding to CHO-K1 and HEK-293T cells (Fig. 5C and D), confirming the involvement of other membrane components in the interaction of HN729–845 and the cell membrane.

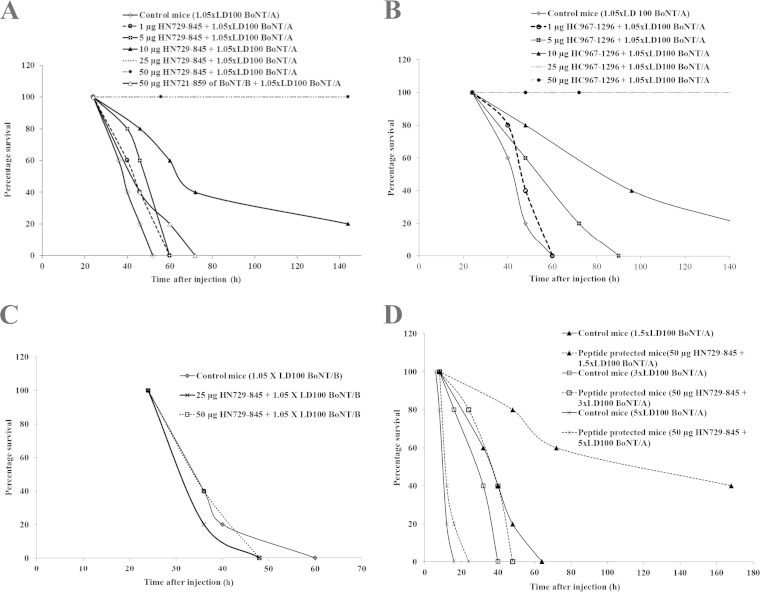

In vivo protection of mice from BoNT/A toxicity by peptide HN729–845.

The toxicity of HN729–845 was tested in vivo in mice before studying its protective efficacy against the toxin. The ability of HN729–845 to block the action of a lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of BoNT/A was tested at different doses of peptide (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 μg). A structurally similar control peptide corresponding to HN721–859 of BoNT/B was tested for its ability to protect against a lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of BoNT/A. HN729–845 at doses of 25 μg and 50 μg completely protected against BoNT/A, whereas HN721–859 of BoNT/B did not show any protective activity against the toxic dose of BoNT/A (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Peptide HN729–845 exhibits protective efficacy against active BoNT/A toxin. (A) An MPA was carried out by premixing different doses of HN729–845 (1 μg, 5 μg, 10 μg, 25 μg, and 50 μg) with a lethal dose of BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) and injecting each dose mixture into 5 mice. Controls consisted of 5 mice injected with BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) without peptide. The mice were kept under observation for 6 days. The assay showed that HN729–845 offered partial protection (20%) against BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) at a 10-μg dose and complete protection (100%) at 25-μg and 50-μg doses. A 138-amino-acid helical peptide corresponding to BoNT/B HN721–859 was used as a control against BoNT/A challenge. BoNT/B HN721–859 did not show any protection against BoNT/A in mice. (B) An MPA was carried out by mixing HC967–1296 at different doses (1 μg, 5 μg, 10 μg, 25 μg, and 50 μg) with a lethal dose of BoNT/A (1.05× LD100). Five mice were injected with each dose of peptide, and a mouse injected with only BoNT/A (1.05× LD100) was used as a control. HC967–1296 at a 10-μg dose offered partial protection (20%) against BoNT/A (1.05× LD100), and HC967–1296 at 25-μg and 50-μg doses offered complete protection (100%). (C) The specificity of BoNT/A HN729–845 was tested by challenging the mice with active BoNT/B (1.05× LD100) mixed with 25 μg and 50 μg of HN729–845. All the mice died within 60 h after the challenge, showing that the protective activity of the peptide is specific against BoNT/A. (D) The protective efficacy of HN729–845 was tested using higher toxin doses. MPA was carried out by premixing 50 μg of HN729–845 with 3 different doses of BoNT/A (5×, 3×, and 1.5× LD100) and injecting each dose mixture into 5 mice. Controls of 5 mice per dose were also injected at the same time with equal doses of BoNT/A without peptide. The mice were kept under observation for 6 days. The assay showed that HN729–845 afforded substantial protection against 1.5× LD100, whereas only a slight delay in the time to death was observed for higher doses.

To compare the protective efficacy of HN729–845 with that of the HC domain of BoNT/A, a similar MPA was carried out in parallel using HC967–1296 at different doses (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 μg) and determining its protective efficacy against a lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of BoNT/A. Peptide HC967–1296 at the 10-μg dose was partially protective against the lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of BoNT/A, and it was completely protective at the 25- and 50-μg doses. The protection obtained with HC967–1296 compared well to the protection obtained with HN729–845 (Fig. 6B). The specificity of protection exhibited by HN729–845 was tested by injecting HN729–845 (25 μg and 50 μg) and determining the protection that it offered against a lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of BoNT/B. HN729–845 had no blocking action against a lethal dose of BoNT/B (Fig. 6C). HN729–845 was specifically protective against BoNT/A.

Further, the protective efficacy of HN729–845 was tested by challenging mice with higher doses of toxin. Four different groups of mice (5 mice per group) were injected with 3 different doses of BoNT/A, 1.5, 3, and 5 times the lethal dose (LD100), premixed with HN729–845. Each experimental group was compared to a control group of mice (5 mice per group), which received the same toxin dose as the experimental group but received toxin to which no peptide was added. The peptide exhibited no protective activity against toxin doses of 5× LD100 or 3× LD100, even though it achieved a slight increase in the survival time (by a few hours). However, HN729–845 completely protected the mice against poisoning with BoNT/A at 1.05× LD100 and provided substantial (40%) protection against a toxin dose of 1.5× LD100 (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

The entry of botulinum neurotoxins into neuronal cells is accomplished by binding to a receptor on the cell membrane followed by endocytosis (3, 30). The binding or entry requires participation of ganglioside GT1b and/or GD1a (31, 32). The protein receptors for BoNT/A (33) have been identified to be SV2, and those for BoNT serotypes B and G have been identified to be synaptotagmins I and II (34). There are several reports that the H chains of BoNTs A and B are responsible for the binding of the toxin to SNPs (20, 35–40). Limited tryptic proteolysis amplified the toxicity of BoNT/B by 2- to 3-fold (41) and that of BoNT/E by 90-fold (42). However, limited trypsin action on BoNT/A caused it to lose toxicity and the ability to bind to rat brain SNPs and sectioned the H chain near the middle into a 46-kDa C-terminal fragment (the HC domain) and a 49-kDa N-terminal fragment (the HN domain) linked by the interchain disulfide to the L chain (35, 43). Consequently, it was inferred that the binding activity of the toxin was restricted to the HC domain of the H chain (35).

A detailed submolecular mapping of BoNT/A and BoNT/B enabled localization of the regions on the entire H chain that are responsible for its binding to SNPs. It was found that BoNT/A, in fact, possesses SNP-binding regions on both the HN and the HC domains (20, 27). Employing dual detection of substrate proteolysis and single-channel currents, Fischer et al. (21) showed that a protein consisting only of the L chain and the HN domain enabled passage of active protease into the cytosol of target cells. The HC domain appeared to be unnecessary for cell entry, channel action, or L-chain translocation, which suggested that each unit chaperones the others to attain toxicity (44). This was further supported by reports where the HN domain–L-chain framework was used as a secretion inhibitor by fusion to a new cell-targeting domain (45–47). Using physicochemical and spectroscopic methods, Galloux et al. (48) found that the HN domain interacts with the membrane; however, the interaction did not involve major secondary or tertiary structural changes. Below its pI of 5.5, the HN domain becomes insoluble and is capable of penetrating lipid vesicles. The constructs mentioned in the studies described above were either the full HN domain (the HN domain from residues 418 to 877) or beltless partial HN domains (the HN domain from residues 454 to 877, 491 to 877, and 547 to 877), and investigators made their inferences on the interaction of the HN domain with the cell membrane on the basis of physicochemical, physiological, or spectroscopic methods. Biochemical evidence of the HN domain interaction with the membrane or information about factors influencing the HN domain-cell interaction to make any strong conclusion is lacking.

Our selection of the HN729–845 region for the present work was based on the aforementioned localization of the submolecular regions of BoNT/A that are involved in BoNT/A binding to mouse brain SNPs and to mouse anti-BoNT/A Abs or blocking Abs from cervical dystonia patients (24). Peptide HN729–845 represents only 9% of the whole BoNT/A molecule and less than a third of the HN domain. It is devoid of a belt sequence, disulfide bond, or the transmembrane region of the HN domain. Free HN729–845 would be expected to have some conformational differences from its three-dimensional (3-D) shape in the intact protein. This part of the toxin has antiparallel helices that are assembled rather tightly in a bundle in the intact BoNT/A molecule (Fig. 1C). However, the free peptide in solution could likely have some flexibility and acquire a somewhat looser conformation that allows fairly itinerant end helices. Besides, purification of HN729–845 using denaturing conditions might affect its structure. Thus, it was important to investigate the secondary structure of the peptide. Under physiological conditions, CD analysis confirmed that HN729–845 is predominantly α helical.

Peptide HN729–845 binds directly to SNPs, and the inhibition of toxin binding to SNPs by peptide HN729–845 was about 30%. Of course, the toxin has other SNP-binding regions, particularly in the HC domain (20). Thus, peptide HN729–845 is not expected to carry the full responsibility of toxin binding. It is possible that the existence of a dimeric species together with the monomer might interfere with its SNP-binding capability (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The peptide offered full protection against a lethal dose (1.05× LD100) of the toxin in vivo, probably due to the swift reduction of the dimer in vivo. However, the experiments did not elucidate the role of peptide HN729–845 in channel formation by the toxin. As BoNT/A is reported to bind GT1b and GD1a (31, 32), the binding of HN729–845 only to these gangliosides was studied. Results obtained from both SNPs and mammalian cell assays demonstrated that GD1a influences the binding of HN729–845 to the cell membrane. In addition, the results of in vitro cell assays suggested that the exposed carbohydrate portion of GD1a increases the binding of HN729–845 to the cell surface. Incubation of HN729–845 with mouse neuroblastoma cells for different time periods showed that peptide binds swiftly (within 1 min) to the membrane.

HN729–845 shows strong binding to phosphatidic acid and moderate to mild binding to sulfatide, cardiolipin, and phosphatidylserine (Fig. 4C). Phosphatidic acids are major constituents of the cell membrane and participate in vesicle fission (49) and fusion (50). Phosphatidic acid has a glycerol backbone and a saturated fatty acid linked to an unsaturated fatty acid and a phosphate group. Sulfatides are sulfated galactosylceramides that play a major role in myelin action and stability (51). Cardiolipin has two phosphate groups, but it effectively behaves like it has one negative charge at physiological pH. It appears that the binding of HN729–845 is primarily aided by the negative charge on the head of the gangliosides or the lipid and is consistent with the findings of Galloux et al. (48), where the membrane surface charges are reported to play an active role in the HN domain-membrane interaction. Involvement of the surface charge in interactions of HN729–845 with the cell explains the binding of the peptide to CHO-K1 and HEK-293T cells. However, binding of HN729–845 to cells lacking GD1a in the presence of excess NaCl (Fig. 5C and Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), which quenches the surface charge, indicates that the HN domain-membrane interaction is not entirely ganglioside reliant or totally charge dependent.

The well-established double-receptor hypothesis (14) and crystallization studies (52–56) demonstrated the binding of the HC domain to polysialogangliosides and the nerve receptor. In addition, a reduced toxicity of BoNT/A in the absence of the HC domain was reported (57), seemingly refuting the substantial contribution of the HN domain in the toxin-cell entry mechanism. However, Chaddock et al. (58) reported that the HN domain-L chain not only exhibited in vivo toxicity at high concentrations but also inhibited neurotransmitter release in embryonic spinal cord neurons. The results of these studies strongly support the possibility of the involvement of a low-affinity receptor in the HN domain-cell interaction. It should be expected that for a complex molecule like BoNT/A it is hard to recapitulate the entire sequence of events and processes that it encounters in a biological system by in vitro studies. Besides, it is not easy to predict the structural and conformational changes induced both in the molecule and at the membrane surface (at various stages), making it difficult to assert any strong assumptions regarding the role of various domains and the receptors involved. This has been proved repeatedly where new receptors and factors influencing toxin internalization are identified (59–62) with an increased understanding of the toxin-host interaction. It is really necessary to confirm the data obtained from such studies in vivo before making any strong interpretations.

To confirm the data from our in vitro analysis, we studied HN729–845 in vivo in a clinically relevant mouse model of toxin poisoning. On the basis of the results of SNP and cell assays, the peptide was expected to compete with and protect against the toxicity of the toxin in vivo. Indeed, HN729–845 was found to be protective against lethal doses of BoNT/A in the mouse, supporting the involvement of this region in the BoNT/A-cell interaction. MPAs with BoNT/B and the HN721–859 peptide of BoNT/B showed that the protective efficacy of HN729–845 is specific to the toxicity of BoNT/A, which is contrary to the common notion that all the BoNTs follow similar translocation protocols. This is an important fact which could be explored in detail to understand the binding and translocation of different BoNT subtypes. The in vivo protective activity of HN729–845 might suggest a potential therapeutic value in toxin poisoning. However, because of its small size, it is expected to be cleared out of the circulation faster than intact BoNT/A. This property can be improved by fusing the peptide to a carrier molecule, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or BSA. The peptide could, in principle, be chemically modified to attach a reactive group at a selected amino acid that will enable it to react covalently with the target molecule. However, more information on the target molecule and on the residues involved in the binding will be needed to choose the location of the modification and the nature of the reactive group.

Peptide HN729–845 was not protective against higher doses of toxin, which shows that it is less protective than some antitoxin antibodies. It is necessary to consider the fact that in such MPA analyses, where the peptide is used as a competing species, it is hard to find higher protection efficacies. Additionally, it should be noted that, in parallel assays, peptide HC967–1296 of BoNT/A exhibited protective activity in vivo that was quite comparable to the activity of peptide HN729–845. A study reported that the HC domain of BoNT/A could attain higher protection levels (up to 105× LD50) when antibodies against the HC domain of serotype A (HC/A) were raised in mice prior to the challenge with toxin (63). However, in a direct challenge with HC/A (2.5 mg) mixed with BoNT/A, a slight prolongation of the time to death rather than protection was observed.

In conclusion, we expressed the region from residues 729 to 845 of the HN domain of BoNT/A and demonstrated that this segment binds to and also substantially inhibits the binding of intact toxin to mouse brain SNPs. We also showed that peptide HN729–845 binds to the membrane of Neuro 2a cells. Most significantly, we confirmed the active role of the peptide by showing that it protected mice against a lethal dose of active BoNT/A. In a parallel assay, this protective activity compared well with the activity of peptide HC967–1296 of BoNT/A. The inhibition of toxicity by peptide HN729–845 was totally specific to BoNT/A. These results strongly indicate that the activity responsible for toxin binding to the neuronal cell wall does not reside solely in the HC domain but that the HN domain actively participates in the binding and this participation is vital for the accomplishment of toxicity. The toxin anchors on at least two sites, one on the HN domain and one on the HC domain, and this is vital for the effective achievement of toxicity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sushrut Arora for proofreading the manuscript and helping with immunofluorescence assays and Melina Agosto for her advice on cell and immunofluorescence assays. We also thank Kazim Sheikh for anti-GD1a antibody, Sonal Nagarkar for providing Neuro 2a cells, and Gang Wu for circular dichroism.

We thank the Integrated Microscopy Core at the Baylor College of Medicine (which is supported by grants 1081701321-P30-CA, 1081701233-DLDCC, 1081701347-U54-HD, and 1081701347-P30-DK and a Digestive Disease Center grant) for image acquisition and technical advice. This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Allergan, the Welch Foundation (grant Q007), and an award to M. Zouhair Atassi of the Robert A. Welch Chair of Chemistry.

We declare that we have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00063-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Swerdlow DL, Tonat K. 2001. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 285:1059–1070. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajjalieh SM. 1999. Synaptic vesicle docking and fusion. Curr Opin Neurobiol 9:321–328. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. 2000. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol Rev 80:717–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atassi MZ, Oshima M. 1999. Structure, activity, and immune (T and B cell) recognition of botulinum neurotoxins. Crit Rev Immunol 19:219–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetto AV. 1999. The cosmetic uses of botulinum toxin type A. Int J Dermatol 38:641–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turton K, Chaddock JA, Acharya KR. 2002. Botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins: structure, function and therapeutic utility. Trends Biochem Sci 27:552–558. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jankovic J, Albanese A, Atassi MZ, Dolly JO, Hallett M, Mayer NH. 2009. Botulinum toxin. Therapeutic clinical practice and science. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin MR, Tepp WH, Przedpelski A, Pier CL, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. 2008. Subunit vaccine against the seven serotypes of botulism. Infect Immun 76:1314–1318. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01025-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barash JR, Arnon SS. 2014. A novel strain of Clostridium botulinum that produces type B and type H botulinum toxins. J Infect Dis 209:183–191. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dover N, Barash JR, Hill KK, Xie G, Arnon SS. 2014. Molecular characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type H gene. J Infect Dis 209:192–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. 1995. Structure and function of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Q Rev Biophys 28:423–472. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montecucco C, Rossetto O, Schiavo G. 2004. Presynaptic receptor arrays for clostridial neurotoxins. Trends Microbiol 12:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer A, Montal M. 2007. Crucial role of the disulfide bridge between botulinum neurotoxin light and heavy chains in protease translocation across membranes. J Biol Chem 282:29604–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montecucco C. 1986. How do tetanus and botulinum toxins bind to neuronal membranes? Trends Biochem Sci 11:314–317. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(86)90282-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin MR, Kim J-JP, Barbieri JT. 2007. Botulinum neurotoxin B-host receptor recognition: it takes two receptors to tango. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14:9–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Meng J, Lawrence GW, Zurawski TH, Sasse A, Bodeker MO, Gilmore MA, Fernández-Salas E, Francis J, Steward LE, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. 2008. Novel chimeras of botulinum neurotoxins A and E unveil contributions from the binding, translocation, and protease domains to their functional characteristics. J Biol Chem 283:16993–17002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumaran D, Eswaramoorthy S, Furey W, Navaza J, Sax M, Swaminathan S. 2009. Domain organization in Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type E is unique: its implication in faster translocation. J Mol Biol 386:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montal M. 2010. Botulinum neurotoxin: a marvel of protein design. Annu Rev Biochem 79:591–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.051908.125345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu S, Rumpel S, Zhou J, Strotmeier J, Bigalke H, Perry K, Shoemaker CB, Rummel A, Jin R. 2012. Botulinum neurotoxin is shielded by NTNHA in an interlocked complex. Science 335:977–981. doi: 10.1126/science.1214270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruta T, Dolimbek B, Aoki KR, Steward L, Atassi MZ. 2004. Mapping of the synaptosome-binding regions on the heavy chain of botulinum neurotoxin A by synthetic overlapping peptides encompassing the entire chain. Protein J 23:539–552. doi: 10.1007/s10930-004-7881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer A, Mushrush DJ, Lacy DB, Montal M. 2008. Botulinum neurotoxin devoid of receptor binding domain translocates active protease. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer A, Sambashivan S, Brunger AT, Montal M. 2012. Beltless translocation domain of botulinum neurotoxin A embodies a minimum ion-conductive channel. J Biol Chem 287:1657–1661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.319400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atassi MZ, Dolimbek B. 2004. Mapping of the antibody-binding regions on the HN-domain (residues 449-859) of botulinum neurotoxin A with antitoxin antibodies from four host species. Full profile of the continuous antigenic regions of the H-chain of botulinum neurotoxin A. Protein J 23:39–52. doi: 10.1023/B:JOPC.0000016257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolimbek BZ, Aoki KR, Steward LE, Jankovic J, Atassi MZ. 2007. Mapping of the regions on the heavy chain of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A) recognized by antibodies of cervical dystonia patients with immunoresistance to BoNT/A. Mol Immunol 44:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittaker VP. 1959. The isolation and characterization of acetylcholine-containing particles from brain. Biochem J 72:694–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolimbek BZ, Steward LE, Aoki KR, Atassi MZ. 2012. Location of the synaptosome-binding regions on botulinum neurotoxin B. Biochemistry 51:316–328. doi: 10.1021/bi201322c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter WM, Greenwood FC. 1962. Preparation of iodine-131 labelled human growth hormone of high specific activity. Nature 194:495–496. doi: 10.1038/194495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bordier C. 1981. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J Biol Chem 256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson LL. 2004. Identification of the major steps in botulinum toxin action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44:167–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginalski K, Venclovas C, Lesyng B, Fidelis K. 2000. Structure-based sequence alignment for the β-trefoil subdomain of the clostridial neurotoxin family provides residue level information about the putative ganglioside binding site. FEBS Lett 482:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01954-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yowler BC, Kensinger RD, Schengrund C-L. 2002. Botulinum neurotoxin A activity is dependent upon the presence of specific gangliosides in neuroblastoma cells expressing synaptotagmin I. J Biol Chem 277:32815–32819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong M, Yeh F, Tepp WH, Dean C, Johnson EA, Janz R, Chapman ER. 2006. SV2 is the protein receptor for botulinum neurotoxin A. Science 312:592–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1123654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rummel A, Karnath T, Henke T, Bigalke H, Binz T. 2004. Synaptotagmins I and II act as nerve cell receptors for botulinum neurotoxin G. J Biol Chem 279:30865–30870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shone CC, Hambleton P, Melling J. 1985. Inactivation of Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin by trypsin and purification of two tryptic fragments. Proteolytic action near the COOH-terminus of the heavy subunit destroys toxin-binding activity. Eur J Biochem 151:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson LL. 1986. Molecular pharmacology of botulinum toxin and tetanus toxin. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 26:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.26.040186.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandyopadhyay S, Clark AW, DasGupta BR, Sathyamoorthy V. 1987. Role of the heavy and light chains of botulinum neurotoxin in neuromuscular paralysis. J Biol Chem 262:2660–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozaki S, Miki A, Kamata Y, Ogasawara J, Sakaguchi G. 1989. Immunological characterization of papain-induced fragments of Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin and interaction of the fragments with brain synaptosomes. Infect Immun 57:2634–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishiki T, Kamata Y, Nemoto Y, Omori A, Ito T, Takahashi M, Kozaki S. 1994. Identification of protein receptor for Clostridium botulinum type B neurotoxin in rat brain synaptosomes. J Biol Chem 269:10498–10503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Singh B. 1999. In vitro translation of type A Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin heavy chain and analysis of its binding to rat synaptosomes. J Protein Chem 18:89–95. doi: 10.1023/A:1020655701852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das Gupta BR, Sugiyama H. 1972. Role of a protease in natural activation of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin. Infect Immun 6:587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozaki S, Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi G. 1974. Purification and some properties of progenitor toxins of Clostridium botulinum type B. Infect Immun 10:750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gimenez J, DasGupta B. 1993. Botulinum type A neurotoxin digested with pepsin yields 132, 97, 72, 45, 42, and 18 kD fragments. J Protein Chem 12:351–363. doi: 10.1007/BF01028197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montal M. 2009. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease by the heavy chain protein-conducting channel. Toxicon 54:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaddock JA, Purkiss JR, Duggan MJ, Quinn CP, Shone CC, Foster KA. 2000. A conjugate composed of nerve growth factor coupled to a non-toxic derivative of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type A can inhibit neurotransmitter release in vitro. Growth Factors 18:147–155 . doi: 10.3109/08977190009003240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duggan MJ, Quinn CP, Chaddock JA, Purkiss JR, Alexander FCG, Doward S, Fooks SJ, Friis LM, Hall YHJ, Kirby ER, Leeds N, Moulsdale HJ, Dickenson A, Green GM, Rahman W, Suzuki R, Shone CC, Foster KA. 2002. Inhibition of release of neurotransmitters from rat dorsal root ganglia by a novel conjugate of a Clostridium botulinum toxin A endopeptidase fragment and Erythrina cristagalli lectin. J Biol Chem 277:34846–34852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaddock JA, Purkiss JR, Alexander FCG, Doward S, Fooks SJ, Friis LM, Hall YHJ, Kirby ER, Leeds N, Moulsdale HJ, Dickenson A, Green GM, Rahman W, Suzuki R, Duggan MJ, Quinn CP, Shone CC, Foster KA. 2004. Retargeted clostridial endopeptidases: inhibition of nociceptive neurotransmitter release in vitro, and antinociceptive activity in in vivo models of pain. Mov Disord 19:S42–S47. doi: 10.1002/mds.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galloux M, Vitrac H, Montagner C, Raffestin S, Popoff MR, Chenal A, Forge V, Gillet D. 2008. Membrane interaction of botulinum neurotoxin A translocation (T) domain: the belt region is a regulatory loop for membrane interaction. J Biol Chem 283:27668–27676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weigert R, Silletta MG, Spanò S, Turacchio G, Cericola C, Colanzi A, Senatore S, Mancini R, Polishchuk EV, Salmona M, Facchiano F, Burger KN, Mironov A, Luini A, Corda D. 1999. CtBP/BARS induces fission of Golgi membranes by acylating lysophosphatidic acid. Nature 402:429–433. doi: 10.1038/46587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blackwood RA, Smolen JE, Transue A, Hessler RJ, Harsh DM, Brower RC, French S. 1997. Phospholipase D activity facilitates Ca2+-induced aggregation and fusion of complex liposomes. Am J Physiol 272:C1279–C1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coetzee T, Fujita N, Dupree J, Shi R, Blight A, Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Popko B. 1996. Myelination in the absence of galactocerebroside and sulfatide: normal structure with abnormal function and regional instability. Cell 86:209–219. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. 2000. Structural analysis of the catalytic and binding sites of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat Struct Mol Biol 7:693–699. doi: 10.1038/78005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chai Q, Arndt JW, Dong M, Tepp WH, Johnson EA, Chapman ER, Stevens RC. 2006. Structural basis of cell surface receptor recognition by botulinum neurotoxin B. Nature 444:1096–1100. doi: 10.1038/nature05411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin R, Rummel A, Binz T, Brunger AT. 2006. Botulinum neurotoxin B recognizes its protein receptor with high affinity and specificity. Nature 444:1092–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenmark P, Dupuy J, Imamura A, Kiso M, Stevens RC. 2008. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A in complex with the cell surface co-receptor GT1b—insight into the toxin-neuron interaction. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berntsson RPA, Peng L, Dong M, Stenmark P. 2013. Structure of dual receptor binding to botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat Commun 4:2058. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaddock JA, Purkiss JR, Friis LM, Broadbridge JD, Duggan MJ, Fooks SJ, Shone CC, Quinn CP, Foster KA. 2000. Inhibition of vesicular secretion in both neuronal and nonneuronal cells by a retargeted endopeptidase derivative of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type A. Infect Immun 68:2587–2593. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2587-2593.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaddock JA, Herbert MH, Ling RJ, Alexander FCG, Fooks SJ, Revell DF, Quinn CP, Shone CC, Foster KA. 2002. Expression and purification of catalytically active, non-toxic endopeptidase derivatives of Clostridium botulinum toxin type A. Protein Expr Purif 25:219–228. doi: 10.1016/S1046-5928(02)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muraro L, Tosatto S, Motterlini L, Rossetto O, Montecucco C. 2009. The N-terminal half of the receptor domain of botulinum neurotoxin A binds to microdomains of the plasma membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 380:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugawara Y, Matsumura T, Takegahara Y, Jin Y, Tsukasaki Y, Takeichi M, Fujinaga Y. 2010. Botulinum hemagglutinin disrupts the intercellular epithelial barrier by directly binding E-cadherin. J Cell Biol 189:691–700. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun S, Suresh S, Liu H, Tepp WH, Johnson E, Edwardson JM, Chapman E. 2011. Receptor binding enables botulinum neurotoxin B to sense low pH for translocation channel assembly. Cell Host Microbe 10:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacky BPS, Garay PE, Dupuy J, Nelson JB, Cai B, Molina Y, Wang J, Steward LE, Broide RS, Francis J, Aoki KR, Stevens RC, Fernández-Salas E. 2013. Identification of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) as a protein receptor for botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A). PLoS Pathog 9:e1003369. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ben David A, Diamant E, Barnea A, Rosen O, Torgeman A, Zichel R. 2013. The receptor binding domain of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A) inhibits BoNT/A and BoNT/E intoxications in vivo. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:1266–1273. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00268-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lacy DB, Tepp W, Cohen AC, DasGupta BR, Stevens RC. 1998. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 5:898–902. doi: 10.1038/2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.