Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative opportunistic nosocomial pathogen that causes pneumonia and soft tissue and systemic infections. Screening of a transposon insertion library of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T resulted in the identification of the 2010 derivative, which, although capable of growing well in iron-rich media, failed to prosper under iron chelation. Genetic, molecular, and functional assays showed that 2010's iron utilization-deficient phenotype is due to an insertion within the 3′ end of secA, which results in the production of a C-terminally truncated derivative of SecA. SecA plays a critical role in protein translocation through the SecYEG membrane channel. Accordingly, the secA mutation resulted in undetectable amounts of the ferric acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA while not affecting the production of other acinetobactin membrane protein transport components, such as BauB and BauE, or the secretion of acinetobactin by 2010 cells cultured in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of the synthetic iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl. Outer membrane proteins involved in nutrient transport, adherence, and biofilm formation were also reduced in 2010. The SecA truncation also increased production of 30 different proteins, including proteins involved in adaptation/tolerance responses. Although some of these protein changes could negatively affect the pathobiology of the 2010 derivative, its virulence defect is mainly due to its inability to acquire iron via the acinetobactin-mediated system. These results together indicate that although the C terminus of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T SecA is not essential for viability, it plays a critical role in the production and translocation of different proteins and virulence.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative opportunistic human pathogen traditionally recognized as an etiologic agent of severe nosocomial infections in compromised hosts (1). More recently, this pathogen has emerged as an important infectious agent among soldiers who have been injured in Middle Eastern war zones (2, 3). The ubiquity of A. baumannii in the hospital environment and its remarkable antibiotic resistance capabilities make it extremely difficult to treat patients infected with this bacterium (4–6). The multidrug resistance of A. baumannii strains has been the major focus of numerous reports; however, fewer studies have described the molecular mechanisms of virulence or the general physiology of this relevant infectious agent.

Iron is an essential micronutrient for the general physiology of A. baumannii, as it is for almost all living organisms (7). In the case of the human host, this metal is sequestered by high-affinity iron-binding products, including lactoferrin, ferritin, and transferrin, all of which are components of the innate immune response that reduces free-iron availability to as low as 10−18 M (8). Successful bacterial pathogens, including A. baumannii, must therefore utilize high-affinity iron acquisition systems to access this metal from the host. Accordingly, the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T type strain produces and uses acinetobactin, a low-molecular-weight ferric iron chelator, as well as uncharacterized hemin utilization systems to scavenge iron from the host (9). Acinetobactin is a catechol-hydroxamate siderophore synthesized and potentially secreted by proteins encoded by genes located within the acinetobactin and entA gene clusters (10–12). After scavenging extracellular iron, ferric acinetobactin complexes are transported through the membranes and internalized into the bacterial cytoplasm by the BauDCEBA transport protein complex. The BauA protein, which is crucial for full virulence, is the acinetobactin cell surface receptor that transports the ferric acinetobactin complexes across the outer membrane and delivers them to BauB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein that harbors a periplasmic iron-binding domain and promotes the internalization of ferric acinetobactin via the BauC, BauD, and BauE cytoplasmic membrane-associated ABC transporter complex (10, 11). Thus, the successful utilization of ferric acinetobactin as an iron source by A. baumannii ATCC 19606T depends on the production and proper export of these proteins.

The majority of protein transport across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane is accomplished by two mechanisms: the general secretion pathway, referred to as the Sec-dependent transport system, and the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway (13). Most proteins are translocated in an unfolded state across the cytoplasmic membrane by the Sec system, while fully folded and/or cofactor-containing proteins are usually transported via the Tat pathway. The study of the Sec-dependent transport system, which was pioneered using Escherichia coli as a working model (14, 15), shows that it is composed of a cytoplasmic membrane protein-conducting channel consisting of SecY, SecE, and SecG (16, 17), as well as SecA (18), an ATPase that associates with the conducting channel and phospholipids in the cytoplasmic membrane and functions as a driving motor for protein translocation in an energy-dependent process (19, 20). Proteins destined for export by the Sec-dependent mechanism are targeted to the protein-conducting channel either cotranslationally or posttranslationally (19). Proteins undergoing cotranslational targeting are bound by a signal recognition particle (SRP), which is recognized by an SRP receptor (SR or FtsY) that brings the ribosome and nascent protein to the conducting channel. Cotranslational transport is usually associated with the integration of proteins into the cytoplasmic membrane. Proteins that are posttranslationally targeted to the conducting channel are recognized by the SecB chaperone, which maintains the protein in an unfolded state (21). SecB bound to a nascent protein recognizes the C terminus of SecYEG-bound SecA, which accepts the nascent protein from SecB and then utilizes the hydrolysis of ATP in conjunction with the proton motive force to thread the unfolded protein through the conducting channel (19, 20). The Sec translocase components are conserved among bacteria (13, 19, 20, 22), with some of these components, including SecA, SecE, and SecY, playing essential roles in protein translocation and overall cell viability (15). Accordingly, it was initially proposed that all bacteria produce a single essential SecA protein (22). However, analysis of Gram-positive bacteria showed that some of them produce the canonical SecA protein (SecA1), which is considered an essential housekeeping protein export factor, as well as an accessory related protein named SecA2 (23). While SecA2 is not essential for cell viability, it does play a role in the physiology of some nonpathogenic and pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria (23).

In this report, we describe the genetic, functional, and proteomic analyses of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T 2010 insertion derivative, which harbors a transposon insertion in the 3′ end of secA that results in the production of a C-terminally truncated SecA protein. As expected because of the critical role that SecA plays in bacterial protein secretion, the truncation of secA resulted in the differential production of proteins that reflected either their SecA dependence for proper cellular location or a potential stress response due to the failure to properly process proteins destined for membrane insertion and/or translocation. Although the secA truncation did not significantly affect the viability of this derivative in rich media, it did impair its iron acquisition capacity and virulence when tested in vivo with the Galleria mellonella experimental infection model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar plates (24) were used to maintain or culture all strains used in this work. M9 minimal medium (25) was used to culture bacteria for the detection of dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) and acinetobactin by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Culture media were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and incubated overnight (12 to 14 h) at 37°C. Iron-chelated conditions were achieved by adding the synthetic iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (DIP), while iron-rich conditions were achieved by adding FeCl3 dissolved in 0.1 N HCl. The strains ATCC 19606T s1, which uses but does not produce acinetobactin, and t6, which produces but does not use acinetobactin, were used as controls in acinetobactin utilization bioassays (10). Bacterial growth at 37°C was determined using either standard LB broth or LB broth containing increasing concentrations of NaCl ranging from 0 mM to 750 mM. All growth assays were done in triplicate with fresh cultures for each replicate, and the optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) were compared using the Student t test; P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. baumannii | ||

| 19606T | Clinical isolate, type strain | ATCC |

| 19606T 2010 | secA::EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> derivative of 19606T; Kmr | This work |

| 19606T 2010.C | 2010 derivative harboring pMU472, parental iron utilization phenotype; Kmr Ampr | This work |

| 19606T s1 | basD::aph, 19606T acinetobactin-production deficient derivative; Kmr | 10 |

| 19606T t6 | bauA::EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> derivative of ATCC 19606T, acinetobactin-utilization deficient; Kmr | 10 |

| E. coli | ||

| EC100D | pir+, used for plasmid rescue | Epicentre |

| Top10 | Used for DNA recombinant methods | Life Technologies |

| BL21 Star (DE3) | λDE3, T7 RNA polymerase | Life Technologies |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCC1 | PCR cloning vector; Cmr | Epicentre |

| pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | PCR cloning vector; Kmr Zeor | Life Technologies |

| pET100D | T7 expression vector; Ampr | Life Technologies |

| pET200D | T7 expression vector; Kmr | Life Technologies |

| pUC4K | Source of aph encoding Kmr | Pharmacia |

| pWH1266 | A. baumannii-E. coli shuttle vector; Ampr Tetr | 32 |

| pMU450 | Plasmid rescued by self-ligation of EcoRI-digested DNA from mutant 2010; Kmr | This work |

| pMU451 | Plasmid rescued by self-ligation of NcoI-digested DNA from mutant 2010; Kmr | This work |

| pMU468 | pCR-Blunt II-TOPO harboring secA from 19606T; Kmr | This work |

| pMU472 | pWH1266 harboring secA from 19606T; Ampr Tets | This work |

| pMU481 | pET200D harboring secA from 19606T; Kmr | This work |

| pMU734 | 1.3-kbp secA internal amplicon from 19606T cloned in pCC1 | This work |

| pMU884 | pET100D harboring bauB internal amplicon from 19606T; Ampr | This work |

| pMU887 | pET100D harboring bauE internal amplicon from 19606T; Ampr | This work |

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Zeor, zeocin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Tets, tetracycline sensitivity.

General DNA procedures.

Total DNA was isolated either by ultracentrifugation in cesium chloride density gradients (26) or by using a miniscale method adapted from a previously published method (27). Plasmid DNA was isolated using commercial kits (Qiagen). DNA digests were performed with restriction enzymes as indicated by the supplier (New England BioLabs) and size fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis (24). DNA restriction and Southern blot analyses were conducted using standard protocols (24) with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA probes (28). Both strands of cloned DNA were sequenced with standard automated DNA sequencing BigDye-based chemistry (Life Technologies) using M13 forward and reverse (29), T7 and T3 (Life Technologies), or custom-designed (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) primers. Sequences were assembled using Sequencher 4.2 (Gene Codes Corp.). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analyzed with DNASTAR (DNASTAR, Inc.), BLAST (30), and the tools available at the EMBOSS (http://emboss.sourceforge.net/) and ExPASy (http://www.expasy.org) websites. Potential promoter elements and transcription initiation sites were predicted using the prokaryotic tool of the Neural Network Promoter Prediction program (http://promoter.biosino.org).

Transposition mutagenesis and rescue cloning of the 2010 insertion derivative.

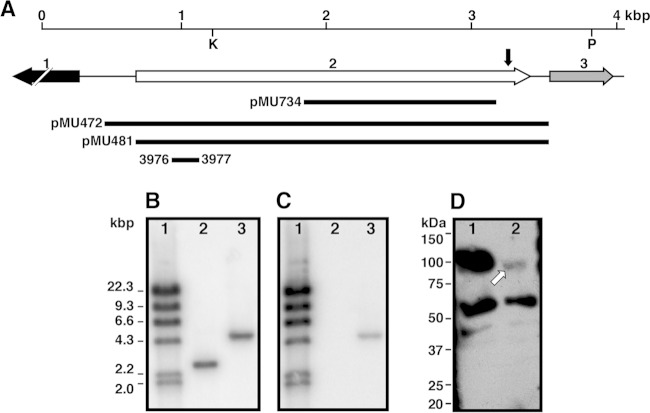

The A. baumannii ATCC 19606T random insertion library was constructed with the EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> Tnp Transposome mutagenesis system (Epicentre) as described previously (31). Insertion derivatives were screened for impaired growth on LB agar containing 150 μM DIP (10), and one of them, designated 2010, was further analyzed. The chromosomal region harboring the transposon insertion was rescued as a plasmid after self-ligation of EcoRI or NcoI (pMU450 or pMU451, respectively [Table 1]) restriction enzyme-digested DNA. Rescued plasmids were sequenced with primers supplied with the mutagenesis kit and custom-designed primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The transposon insertion was also confirmed by Southern blotting hybridization of KpnI/PvuII-digested DNA isolated from the parental strain and the 2010 insertion derivative. The aph kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene, which was obtained by PCR amplification from pUC4K (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with primers 133 and 134 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and pMU734 (Table 1; Fig. 1A) were used as radiolabeled probes. The plasmid pMU734 was generated by cloning a 1.3-kb secA internal fragment (Fig. 1A) into pCC1 with the Epicentre CopyControl PCR cloning kit using ATCC 19606T total DNA as a template, Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen), and primers 3279 and 3280 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Analysis of the genetic locus affected in the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T 2010 insertion derivative. (A) Genetic map of the locus harboring the secA gene (ORF 2), which was truncated due to a transposon insertion near its 3′ end (vertical black arrow), and the ORF1 and ORF 3 flanking coding regions. The horizontal arrows represent the location and direction of transcription of predicted coding regions. The locations of the KpnI (K) and PvuII (P) restriction sites used to confirm the EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> insertion site are indicated. The three long black horizontal bars represent cloned DNA regions used as probes in Southern blotting (pMU734), to complement the 2010 insertion derivative (pMU472), or to overproduce a His-tagged SecA derivative (pMU481). The short black horizontal bar flanked by primer numbers indicate the 5′-end secA region used to test transcriptional expression by qRT-PCR. (B and C) Southern blotting of KpnI-PvuII-digested total DNA isolated from the ATCC 19606T parental strain (lanes 2) and the 2010 derivative (lanes 3) probed with pMU734 (B) or the aph gene (C). (D) Western blotting of cytoplasmic proteins isolated from the ATCC 19606T parental strain (lane 1) and the 2010 derivative (lane 2) probed with anti-SecA antibodies. The white arrow indicates the truncated SecA protein produced in the 2010 insertion derivative.

Genetic complementation of the ATCC 19606T 2010 secA mutant.

The complete secA parental allele was PCR amplified using ATCC 19606T total DNA as a template, Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and primers 2722 and 2724, both of which included BamHI restriction sites (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The 3.06-kb amplicon cloned into pCR-Blunt II TOPO was subcloned as a BamHI restriction fragment into the cognate site of the A. baumannii-E. coli shuttle vector pWH1266 (32) to generate pMU472 (Table 1; Fig. 1A). This plasmid was electroporated into ATCC 19606T 2010 cells as described before (10), resulting in the 2010.C complemented derivative, which was isolated after plating on LB agar containing 500 μg/ml ampicillin. The presence and stability of pMU472 in the 2010.C complemented strain were confirmed by Southern blotting of BamHI-restricted plasmid DNA with the secA probe described above.

Transcriptional analyses.

A. baumannii ATCC 19606T and the 2010 isogenic derivative were each grown as three independent 1-ml cultures for 24 h at 37°C in LB, and bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min. Bacteria were resuspended and lysed in 200 μl of lysis buffer (0.3 M sodium acetate [pH 4.0], 30 mM EDTA, 3% SDS) for 2 min in a boiling-water bath. Each sample was immediately added to a 200-μl aliquot of lysis buffer provided with the Maxwell 16 LEV simplyRNA tissue kit, and total RNA was purified following the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). The integrity of the RNA samples was determined with an RNA 6000 Pico kit using the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). The iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with 10 ng of total RNA as a template following the manufacturer's protocol. The iQ SYBR green Supermix together with the CFX Connect PCR detection system (both from Bio-Rad) were used following the manufacturer's recommendations. Primers 3976 and 3977 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to test the transcription of the secA 5′ region in ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells. Primer sets 3970-3971, 4024-4025, and 4026-4027 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify internal fragments of bauA, bauD, and bauB, respectively, in reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) experiments. Primers 3968 and 3969 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify a 160-bp internal fragment of recA, which served as an internal control of constitutive gene expression. The following cycling conditions were used for quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) amplification: 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 45 s. Analysis of transcription data was performed in triplicate, where relative expressions were quantified by the standard curve method in which serial dilutions of cDNA samples served as standards. The expression of secA was normalized to that of recA, and samples containing no template RNA were used as negative controls. Statistical analyses of qRT-PCR data were performed using the Student t test provided as part of the GraphPad InStat software package (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The production of the predicted amplicons was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis (24).

Detection of acinetobactin production and utilization functions.

The iron-regulated production of phenolic and siderophore compounds was tested with the Arnow colorimetric assay (33) and the Chrome azurol S (CAS) reagent (34), respectively, using culture supernatants of bacteria grown in a succinate-based chemically defined medium (35). Acinetobactin production was tested with siderophore cross-feeding bioassays using the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T t6 (bauA) and s1 (basD) insertion derivatives as reporter strains as described before (10). Sterile filter discs impregnated with 10 μl of 10 mM FeCl3, sterile distilled water, purified acinetobactin, or cell-free supernatants from 2010 overnight cultures, which contained a subinhibitory concentration of DIP, were deposited on the surface of LB agar plates containing each test or reporter strain and 200 μM DIP. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C before the diameters of growth halos were measured. All assays were repeated a minimum of three times using different biological samples each time.

The production of DHBA and acinetobactin by A. baumannii ATCC 19606T and the 2010 mutant was determined by HPLC using M9 minimal medium culture supernatants as described before (12). Briefly, filtered culture supernatants were fractionated over an Acclaim C8 reverse-phase column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using water and acetonitrile containing 0.13% and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), respectively, as mobile phases. The gradient was as follows: 17% acetonitrile for 5 min, then from 17% to 30% within 30 min, and thereafter held for 15 min. The presence of eluted material was detected at 317 nm.

Generation of antisera against SecA, BauA, BauB, and BauE.

A 2.8-kb amplicon harboring the entire secA gene, which was generated with primers 2650 and 2725 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), was ligated into the Champion pET200/D-TOPO cloning vector (Life Technologies) to make pMU481 (Fig. 1A). The bauB region coding from valine 227 to the C-terminal end and the bauE coding region from the N terminus to alanine 119 were PCR amplified using primer sets 3573-3507 and 3512-3574 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), respectively. The bauB and bauE amplicons were cloned into the Champion pET100/D-TOPO plasmid to generate pMU884 and pMU887, respectively. All overexpressing vectors coding for His-tagged proteins were transformed into E. coli One Shot BL21 Star (DE3) competent cells (Life Technologies) for protein overproduction after induction with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Recombinant His-tagged SecA was purified from the insoluble fraction of cell lysates prepared with the B-PER protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using affinity chromatography over nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose (Qiagen) under denaturing conditions as described before (36). The purity of the 110-kDa isolated protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (37).

BauB- and BauE-overproducing bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0), and disrupted with a French press at 2,000 lb/in2. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The lysate-soluble fraction containing recombinant BauB protein was applied to a 1-ml Ni-NTA agarose column previously equilibrated with equilibration buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). The column was washed with equilibration buffer, and recombinant BauB was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 0.3 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). The lysate-insoluble fraction containing most of the recombinant BauE protein was solubilized in equilibration buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, 8 M urea, pH 8.0) and purified as described previously (36). Affinity chromatography of BauB and BauE preparations yielded purified proteins as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE analyses, which showed only a single 14.7-kDa or 20.9-kDa protein band, respectively. Production of anti-BauA antibodies was described before (10). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the His-tagged SecA, BauB, and BauE were raised and immunopurified as previously described (37, 38).

Detection of SecA, BauA, BauB, and BauE.

For the detection of the BauA, BauB, and BauE acinetobactin transport proteins, bacteria cultured in LB broth under iron-rich and iron-chelated conditions were used to prepare whole-cell lysates as well as inner and outer membrane fractions as described before (36, 37). After SDS-PAGE size fractionation on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels (37), proteins were blotted to nitrocellulose (39) and then incubated overnight with the appropriate antibodies at 4°C. For the detection of SecA, bacteria cultured in LB broth were lysed using a French press at 1,250 lb/in2. The cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and 10 μg of total proteins from each sample were size fractionated by SDS-PAGE using 4% to 15% polyacrylamide gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (40). Proteins were either visualized after staining with Coomassie blue or transferred to nitrocellulose and then probed with anti-SecA polyclonal antibodies. The immunocomplexes were detected by chemiluminescence using either protein A or goat anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibodies (Millipore) labeled with horseradish peroxidase. The intensities of protein bands detected by chemiluminescence on an X-ray film were compared using ImageJ 1.48.

Comparative proteomic analyses.

Proteomic analyses of ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells grown in LB broth were conducted as described before (41). Briefly, five 100-ml culture replicates for each condition were incubated at 37°C for 14 h, the time at which they reached stationary phase (OD600 between 1.6 and 1.8), pooled, and then centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to collect cells. The inner membrane, outer membrane, and cytoplasmic protein fractions from ATCC 19606T and 2010 bacteria were prepared and analyzed via two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) as described previously (41). Protein spots were visualized by Coomassie blue staining, and gel image analysis was performed using the PDQuest software package (Bio-Rad). All 2-DE experiments were performed in triplicate, and pairwise comparisons of standardized log10 values of protein spot volumes were analyzed using the Student t test. Spots with at least a 2-fold change at the 95% confidence interval (P ≤ 0.05) were considered to be differentially produced and were subjected to mass spectrometry analysis.

Differentially produced proteins were identified by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) following matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer) of trypsin-digested protein spots as reported before (41). PeakErazor software (v 2.01; Lighthouse Data) was used to exclude protein contaminants, and the MASCOT search engine (Matrix Science) was used to match PMFs to bacterial entries in the NCBI nonredundant database. Proteins were assumed to be positively identified if the peptide mixtures matched that of Acinetobacter sp. proteins with the highest statistically significant search scores (P ≤ 0.05) and accounted for the majority of the mass spectrum peaks.

Galleria mellonella virulence assays.

A. baumannii cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or PBS supplemented with 50 μM FeCl3. Appropriate bacterial inocula were estimated spectrophotometrically by OD600 and confirmed by plate counting using LB agar plates. To assess virulence, G. mellonella survival assays were performed by injecting in triplicate 10 randomly selected healthy final-instar G. mellonella larvae (n = 30) as previously described (42). Experimental groups consisted of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T parental strain and the isogenic insertion derivatives 2010 and t6, all of which were injected in the absence or presence of 50 μM FeCl3. Controls included noninjected larvae or larvae injected with 5 μl of sterile PBS with or without 50 μM FeCl3 supplementation. If more than two deaths in a control group were observed, the trial was discontinued and repeated. After injection, the larvae were incubated at 37°C in darkness. Death was assessed at 24-hour intervals over 5 days, with removal of dead larvae at the times of inspection. The resulting survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method (43), and P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant for the log rank test of survival curves (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Isolation and analysis of the ATCC 19606T 2010 secA insertion mutant.

In our preliminary study (9), we reported that the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T 2010 isogenic insertion derivative, which was isolated because of its inability to grow in the presence of the synthetic iron chelator DIP, harbors an EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> insertion 140 nucleotides from the 3′ end of a 2,724-nucleotide gene (open reading frame [ORF] 2 in Fig. 1A). Detection by Southern blotting of a single 2.4-kb KpnI-PvuII restriction fragment, the size of which was increased by 2 kb because of the transposon insertion in the 2010 derivative (Fig. 1B and C), indicates that this is the only ATCC 19606T coding region disrupted by the transposition insertion. Further in silico analyses including the information available at the Broad Institute as part of the Human Microbiome Project (http://www.broadinstitute.org/) showed that the gene interrupted in the 2010 derivative is a canonical secA, which was annotated as HMPREF0010_02761.1. BLASTp analyses showed that the predicted product of the ATCC 19606T secA ortholog is a 907-amino-acid protein that contains the protein cross-linking and the wing and scaffold domains as well as the SecC motif found in other SecA proteins, including that produced by E. coli (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). However, the ATCC 19606T secA also has an evident DEAD/DEAH box helicase domain also present in the orthologs produced by other bacteria but not readily apparent in the E. coli SecA product (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

The secA coding region is followed by a predicted gene (ORF 3) that is transcribed in the same orientation (Fig. 1A), the product of which is highly similar to a putative protein that could be produced by members of the Acinetobacter genus. An inverted repeat resembling a Rho-independent transcription termination sequence is located downstream of ORF 2 within the 130-nucleotide region that separates these two coding sequences. Upstream of secA there is a 408-nucleotide intergenic region followed by an oppositely transcribed predicted coding region (ORF 1), which was partially sequenced during this work. This intergenic region includes a putative ribosomal binding site, located seven nucleotides upstream of the secA translation initiation codon, and predicted promoter elements that could drive the transcription and translation of this gene (data not shown). The predicted product of ORF 1 shows the highest similarity to the A. baumannii ACICU hypothetical peroxiredoxin protein ACICU_03111, which has been identified in the genomes of a wide range of bacteria. The genetic arrangement shown in Fig. 1A is also present in the genomes of other A. baumannii strains, including ACICU (44), ATCC 17978 (45), AYE (46), and AB0057 and AB307-0294 (47) as well as in the genomes of Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 (48) and Acinetobacter oleivorans DR1 (YP_003730859). Interestingly, the A. baumannii SDF secA ortholog is preceded by a gene transcribed in the same direction as secA coding for a putative transposase (49), a feature that may reflect the potential mobility of the A. baumannii chromosomal region harboring this gene.

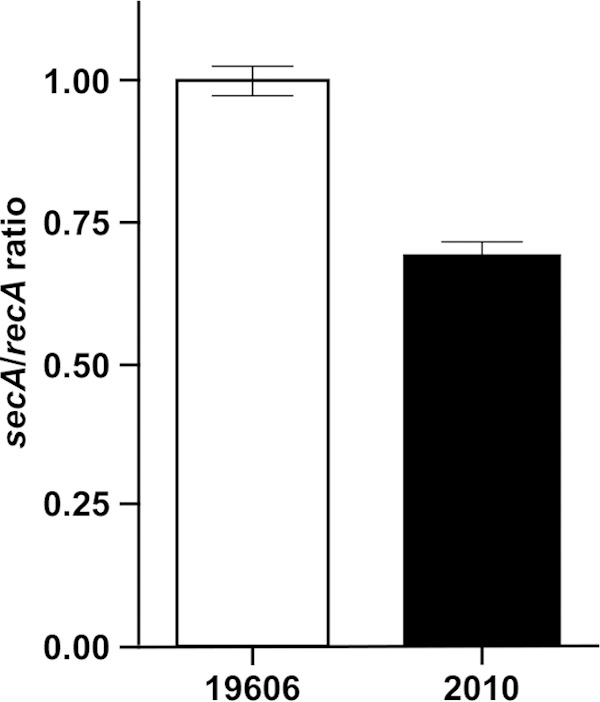

Western blotting using anti-SecA polyclonal antibodies showed that ATCC 19606T cells produce an approximately 103-kDa SecA protein band, whereas the 2010 cells produce a SecA derivative truncated by approximately 6 kDa, as predicted from the nucleotide sequence analysis of this mutant (Fig. 1D). Densitometry of these two SecA-related protein bands showed that the 97-kDa truncated protein represents 4% of the full-length SecA protein detected in the parental protein sample even though comparable amounts of proteins obtained from wild-type and 2010 cells were size fractionated by SDS-PAGE (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The Western blotting also resulted in the detection of other protein bands present in the ATCC 19606T and 2010 protein samples. The approximately 60-kDa and 40-kDa protein bands detected in cell lysates of both strains may represent different proteins that share common amino acid sequences, such as the DEAD/DEAH box helicase domain mapped between the SecA amino acid residues 93 and 215 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This protein segment includes an ATP-binding region that is present in a diverse family of proteins that play functional roles unrelated to SecA. The effect of the transposon insertion in the 2010 mutant on the transcription of secA was also examined by quantitative RT-PCR with primers 3976 and 3977, which anneal to the secA 5′ end (Fig. 1A), using total RNA extracted from ATCC 19606T or 2010 cells as a template. This analysis showed that although the transposon insertion did not abolish the production of secA transcripts, their abundance in 2010 cells was reduced to 69% (P ≤ 0.001) of that detected in ATCC 19606T parental bacteria (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Transcriptional analysis of the secA gene in ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells. qRT-PCR was used to detect secA transcripts produced in the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the isogenic 2010 secA insertion mutant using the primers 3976 and 3977, which anneal to the 5′ end of the this gene, using recA expression for normalization. The error bars represent the standard error (SE) of the mean of data collected from three independent biological samples.

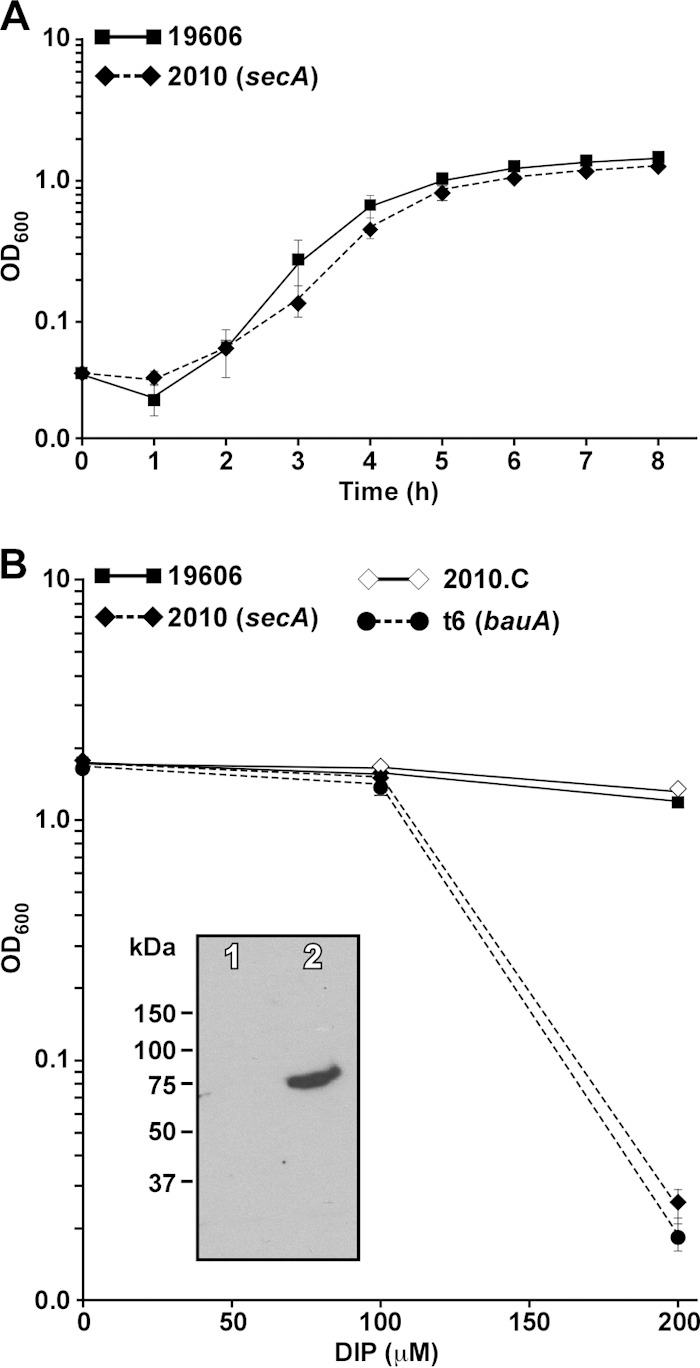

Our preliminary study (9) reporting the isolation of the 2010 derivative under nonselective conditions and growth data collected during this work (Fig. 3A) showed that there were not statistically significant differences between the growth rates of the parental ATCC 19606T strain and the 2010 isogenic derivative when cultured in LB broth. However, incubation of 2010 cells in LB broth containing 200 μM DIP resulted in a drastic growth reduction (P ≤ 0.001) compared with that of the ATCC 19606T strain after overnight incubation (Fig. 3B). This response was similar to that observed with the ATCC 19606T t6 isogenic derivative, which harbors an insertion within the gene coding for the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA (10), compared with the parental strain. Transformation of 2010 with pMU472, a pWH1266 derivative harboring the secA wild-type allele, which was stably maintained as an independent replicon without detectable rearrangements (data not shown), restored the wild-type iron acquisition phenotype as well as the presence of BauA in the outer membrane fraction of the 2010.C complemented derivative (Fig. 3B, inset). These functional and genetic results together with the insertion mapping data (Fig. 1) strongly indicate that the inability of the ATCC 19606T 2010 mutant to grow under iron-chelated conditions is due to a single transposon insertion within the sole secA ortholog identified in this strain.

FIG 3.

Growth of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T and 2010 under different culture conditions. (A) Growth curves of the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the 2010 derivative incubated in LB broth. The OD600 of 1-ml samples taken from a 50-ml LB broth culture was determined hourly for 8 h. (B) Growth of the ATCC 19606T parental strain, the 2010 mutant, its complemented derivative 2010.C, and the t6 BauA mutant incubated in LB broth in the absence of DIP or the presence of 100 μM or 200 μM DIP. Bacterial growth (OD600) was determined after overnight incubation (12 to 14 h) at 37°C in a shaking incubator set at 200 rpm. The error bars show standard errors (SEs) of the means from an assay done in triplicate. Inset, detection of BauA in outer membrane fractions isolated from 2010 (lane 1) and 2010.C (lane 2) cells. SDS-PAGE size-fractionated proteins were probed with anti-BauA polyclonal antibodies.

Effect of the secA mutation in the expression of iron acquisition functions.

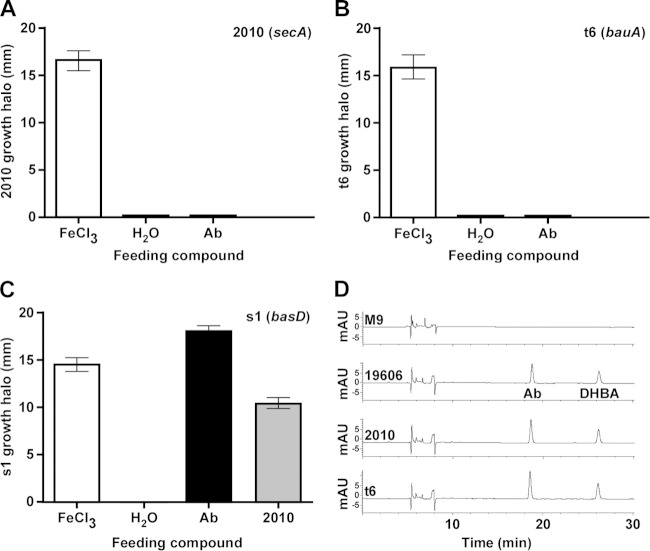

The inability of 2010 to use acinetobactin was confirmed with siderophore utilization bioassays, which resulted in the detection of growth halos of this derivative around filter discs impregnated with FeCl3 but not when the discs were loaded with purified acinetobactin (Fig. 4A). This response is comparable to that obtained using the ATCC 19606T t6 derivative (Fig. 4B), which does not produce the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA (10). In contrast, siderophore utilization bioassays using the ATCC 19606T s1 acinetobactin production mutant showed that 2010 culture supernatants restored bacterial growth, a response similar to that obtained with purified acinetobactin (Fig. 4C). Figure 4D shows that the peaks corresponding to acinetobactin and its precursor DHBA present in the chromatogram of the ATCC 19606T and t6 culture supernatants are also present in the 2010 culture supernatant. These observations indicate that the 2010 secA mutant is affected in the uptake but not in the production and secretion of acinetobactin.

FIG 4.

Cross-feeding bioassays and HPLC analysis of iron-restricted culture supernatants. (A to C) Cross-feeding bioassays were done with LB agar plates containing 200 μM DIP and seeded with 2010 (A), t6 acinetobactin uptake-deficient mutant (B), or s1 acinetobactin synthesis-deficient mutant (C) overnight-cultured bacteria. Sterile filter discs impregnated with 10 μl of 10 mM FeCl3, sterile distilled water, purified acinetobactin (Ab), or cell-free supernatants from 2010 overnight cultures, which contained a subinhibitory concentration of DIP, were deposited on the surface of each plate. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C before results were recorded. The error bars show the standard errors (SEs) of the means from an assay performed in triplicate. (D) HPLC analysis of M9 minimal medium supernatants from ATCC 19606T (19606), 2010, and t6 overnight cultures. The elution peaks corresponding to acinetobactin (Ab) and the precursor DHBA are indicated. HPLC of sterile M9 minimal medium was used as a negative control.

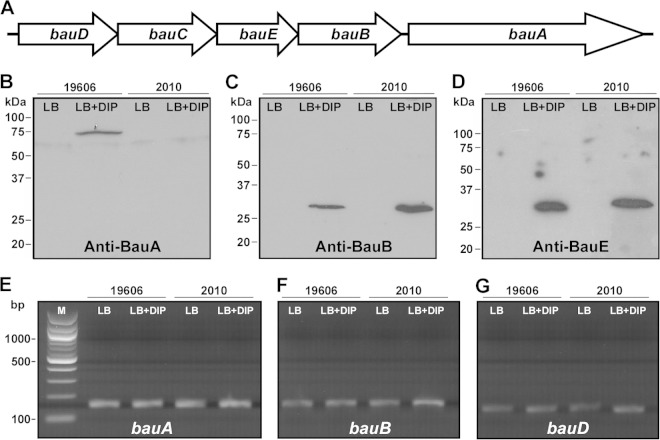

The transport of ferric acinetobactin complexes from the extracellular milieu also depends on the production of BauB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein that harbors an iron-binding domain facing the periplasmic space, and the BauC, BauD, and BauE proteins, which constitute the acinetobactin ABC transporter system associated with the cytoplasmic membrane (10) and are coded for by the polycistronic bauDCEBA operon (Fig. 5A). Considering their subcellular locations, which could depend on a fully active SecA protein, we tested the effect of the secA transposon insertion on the production of BauA, BauB, and BauE by the 2010 derivative. The presence of BauA in the outer membrane fraction depends on the production of a full-length SecA protein in both the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the isogenic 2010.C mutant harboring a plasmid copy of the wild-type secA allele (Fig. 3B, inset). Furthermore, the absence of BauA in the outer membrane of 2010 bacteria is independent of the iron content of the culture medium (Fig. 5B). Probing of cytoplasmic membrane fractions isolated from the same ATCC 19606T and 2010 cell samples used to collect the BauA data with anti-BauB (Fig. 5C) or anti-BauE (Fig. 5D) resulted in the detection of iron-regulated protein bands with the predicted molecular sizes. The effect of the secA insertion on the production of BauC and BauD could not be tested because of the failure to overproduce these proteins for antibody production.

FIG 5.

Detection of acinetobactin transport proteins and transcripts. (A) Genetic organization of the bauDCEBA operon coding for acinetobactin transport functions. (B to D) SDS-PAGE of size-fractionated outer membrane (B) and cytoplasmic membrane (C and D) proteins, which were isolated from ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells cultured in LB broth or LB broth containing 100 μM DIP, were blotted onto nitrocellulose filters and probed with anti-BauA (B), anti-BauB (C), or anti-BauE (D) antibodies. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left-hand side of each blot. (E to G) Agarose gel electrophoresis of bauA (E), bauB (F), and bauD (G) RT-PCR amplicons using as the template total RNA isolated from ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells cultured in LB broth or LB broth containing 100 μM DIP. Lane M, molecular size marker.

As expected from the immunoblot results with anti-BauB, RT-PCR of total RNA isolated from ATCC 19606T and 2010 cells cultured under the same conditions used to collect the data shown in panels Fig. 5B to D resulted in the detection of the expected 166-bp bauB amplicon in all tested samples (Fig. 5F). A similar result was obtained when the same RNA samples were tested using primers annealing to an internal region of bauD (Fig. 5G), the first gene of the bauDCEBA polycistronic operon (Fig. 5A). The same RT-PCR analysis produced the predicted 156-bp bauA amplicon when RNA isolated from parental and 2010 cells cultured in LB with or without DIP supplementation was used as a template (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results indicate that although the 2010 secA insertion mutant produces and secretes acinetobactin, it cannot use this siderophore because of the absence of detectable BauA receptor protein rather than a negative effect on the production of periplasmic and cytoplasmic membrane components of the acinetobactin transport system. These results also indicate that the lack of detection of BauA in whole-cell lysates (data not shown) as well as in the outer membrane fraction of 2010 cells is probably due to protein degradation or posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms rather than abolishment of bauA transcription.

Effect of the secA mutation on global protein production.

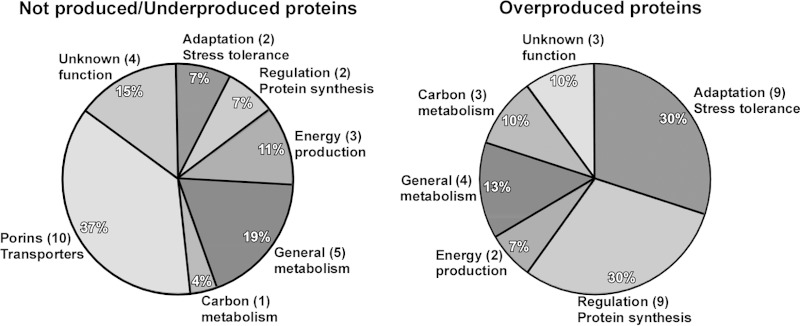

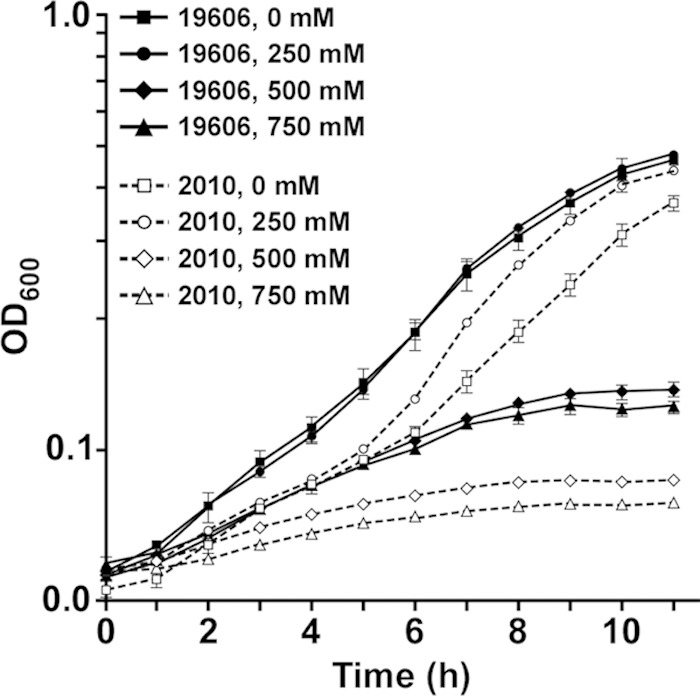

Considering the role SecA plays in the translocation of different proteins, we examined differences in protein production between the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the isogenic 2010 secA insertion derivative using the 2-DE mass spectrometry approach that we applied to study the effect of iron on protein production in this pathogen (41). This proteomics study identified 35 protein spots, which represent 27 different proteins that were underproduced or not produced in the 2010 mutant compared with the parental strain (Fig. 6), 15 of which were detected in the outer membrane fraction (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The SecA mutation impaired the production of proteins involved in different cellular processes, with 37% of them representing membrane porins or transporters, followed by proteins related to general metabolism (19%) and energy production (11%). Albeit to a lesser extent than for the previous protein categories, the SecA mutation also negatively affected the production of proteins involved in regulatory/protein synthesis process, adaptation/stress tolerance, and carbon metabolism (Fig. 6; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The membrane porins or transporters negatively affected by the secA mutation include Omp38, also annotated as OmpA (50), FadL (51), BtuB (52), CirA (53), a ferric aerobactin receptor (54), and OmpW (55) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). All these are bona fide outer membrane proteins, a cellular location that requires the activity of the Sec protein secretion system. The reduction in the production of OmpW, which might act like OmpF in osmotic stress responses as seen in Vibrio alginolyticus growing at different NaCl concentrations (56), could contribute to the significantly reduced growth of the 2010 mutant compared with the ATCC 19606T parental strain after incubation in LB broth containing 500 mM NaCl for 4 h (P ≤ 0.05) or 750 mM NaCl for 3 h (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 7). Proteins underproduced or not produced by the SecA mutant also include SdhA, FabG, PcaF, AcoA, a short-chain dehydrogenase, and a dioxygenase, all of which are predicted to be involved in cellular metabolism (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Table S2 also includes proteins related to energy production, such as the α and β subunits of the FoF1 ATP synthetase, as well as proteins with unknown functions.

FIG 6.

Proteins differentially produced by the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the 2010 secA isogenic mutant. Proteins were grouped based on their predicted cellular functions. Numbers between parentheses indicate the number of proteins included in each functional category.

FIG 7.

Growth of the ATCC 19606T parental strain and the 2010 SecA isogenic mutant with different salt concentrations. Experiments were done using 96-well plates containing 200 μl LB broth that were inoculated with 20 μl of overnight cultures and then incubated at 37°C in a plate-shaking incubator. The OD600 was determined hourly for 11 h. The error bars show the standard errors (SEs) of the means from an assay done in triplicate.

The SecA truncation also resulted in the increased production of 30 proteins, represented by 35 protein spots, in 2010 cells compared with ATCC 19606T bacteria cultured in LB broth (Fig. 6; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). A set of nine adaptation/stress-related proteins, which represent 30% of the differentially overproduced proteins (Fig. 6), is one of the groups most affected due to the secA mutation. This protein set includes GroEL, DnaK, and heat shock-related proteins (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), a response that could reflect the stress caused by the cytoplasmic accumulation of membrane proteins that depend on a functional SecA for translocation. Equally apparent is the increased production of nine proteins related to regulation/protein synthesis, which also represent 30% of the proteins differentially overproduced by the 2010 mutant (Fig. 6), with seven of these nine proteins being related to RpsA, RspB, RplD, RplE, RpsF, and RplV ribosomal proteins and others being associated with cysteine biosynthesis and the regulation of nitrogen assimilation (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The 2010 mutant also overproduced proteins related to energy production as well as carbon and general metabolism and proteins that could be involved in the production of betaine and indole-3-acetic acid by the action of a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (protein spot 58) and an indolepyruvate decarboxylase (protein spot 59), respectively (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Role of SecA in virulence.

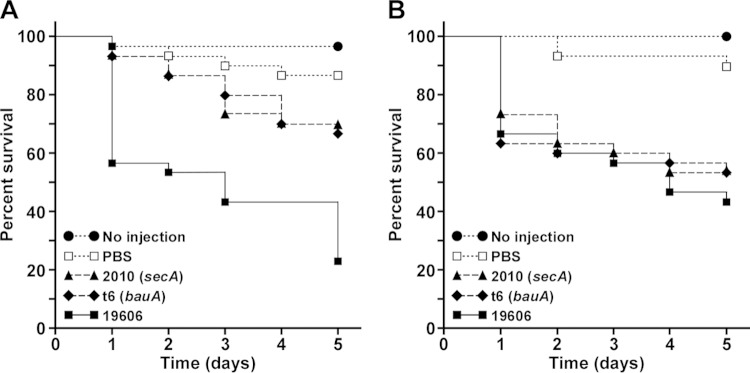

The potential virulence effect of the EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2> insertion at the 3′ end of secA was examined using the G. mellonella virulence model, which we used successfully to determine the virulence role of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system (42). Figure 8A shows that infection with ATCC 19606T bacteria resulted in a significant increase in mortality compared with that of noninjected or PBS-injected larvae, which were used as negative controls, as well as compared with that of larvae injected with the 2010 secA insertion derivative just 1 day after infection (P ≤ 0.001). The virulence difference between the parental strain and the 2010 isogenic mutant was observed throughout the test, with the parental strain having a 2.6-fold-greater death rate than 2010 after 5 days of infection (Fig. 8A). This experimental model also showed that animal death rates produced by the injection of sterile PBS were not significantly different from those caused by the infection with either the 2010 secA mutant or the t6 insertion derivative, which does not acquire iron in an acinetobactin-dependent manner because of a mutation in the gene coding for the BauA acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein (10). The addition of 50 μM FeCl3 to the inocula restored the virulence of the 2010 and t6 isogenic insertion derivatives to levels comparable to that of the wild-type parental strain (Fig. 8B), a response similar to that detected during the analysis of acinetobactin-mediated iron uptake mutants (42). The killing rates detected with the ATCC 19606T parental strain after 5 days of infection in the presence or absence of FeCl3 are not significantly different.

FIG 8.

Role of SecA in virulence. G. mellonella caterpillars (n = 30) were injected with 1 × 105 bacteria of the ATCC 19606T parental strain (19606), the t6 bauA insertion derivative, or the 2010 secA insertion derivative in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 50 μM FeCl3. Negative controls included noninjected caterpillars or caterpillars injected with comparable volumes of PBS or PBS plus 50 μM FeCl3. Caterpillar death was determined daily for 5 days during incubation at 37°C in darkness.

DISCUSSION

In this work we have characterized the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T 2010 mutant harboring a transposon insertion at the 3′ end of the only secA gene identified in the genome of this type strain as well as other A. baumannii genomes. This mutation resulted in a significant reduction in secA transcripts (Fig. 2) and the production of low levels of a 47-amino-acid truncated SecA derivative (Fig. 1). Since the differential production of SecA is a self-mediated translationally regulated process (57), the reduced secA mRNA levels in the 2010 mutant could be due to the generation of secA transcripts that are less stable than the wild-type transcriptional product. This reduced transcript stability could partially but not fully account for the diminished production of the truncated SecA derivative, which may also be less stable than the full-length SecA protein produced in the parental strain, a possibility that should not be ruled out at the moment. The finding that the 2010 mutant is viable under nonselective conditions also indicates that the amount and activity of the truncated SecA protein present in this derivative are enough to maintain basic Sec-dependent protein export functions that are considered essential for cell viability (15, 22). This possibility is supported by the significantly reduced but not abolished production of proteins such as OmpA, the export of which is SecA dependent (58). It is worthy to note that the nonlethal effect of disrupting the 3′ end of secA is not exclusive to the ATCC 19606T strain. Recent screening of an insertion library of A. baumannii ATCC 17978, which also harbors a single identifiable secA gene, resulted in the identification of derivatives harboring a transposon insertion mapped between the location of the mutation in 2010 and the 3′ end of the secA coding region (Fig. 1A) that grew as well as the parental strain when cultured in LB broth or agar (W. F. Penwell, unpublished data).

In contrast to data obtained with rich medium without selective pressure, the growth of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T 2010 derivative was significantly reduced when the culture medium was supplemented with the iron chelator DIP (Fig. 3). This defect proved to be associated with the apparent absence of the BauA acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein without affecting the production of the BauB and BauE acinetobactin transport proteins (Fig. 5). Considering the protein composition and location of the acinetobactin ABC transporter (11, 36), it is possible to speculate that the 2010 derivative also produces the BauC and BauD cytoplasmic-associated acinetobactin transport proteins. The production and secretion of acinetobactin by the 2010 SecA mutant (Fig. 4) also indicate that this mutant produces the BarA and BarB cytoplasmic membrane-associated proteins, which are predicted to be involved in acinetobactin secretion (11, 36). Taken together, these results indicate that, with the exception of BauA, the acinetobactin secretion and transport proteins are translocated by a SecA-independent mechanism, which most likely involves the signal recognition particle system because of their membrane location (59).

The association between the lack of BauA and the iron utilization defect of 2010, both of which were corrected when this mutant was complemented with the wild-type secA allele (Fig. 3B), demonstrates a direct correlation between active SecA-mediated protein transport and iron uptake processes, which to the best of our knowledge has not been described in bacteria. Since the structural domain map of the A. baumannii SecA protein mirrors the map of the better-characterized E. coli SecA protein (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), it is possible to speculate that the 47-amino-acid C-terminal SecA truncation in the 2010 mutant eliminated the SecB- and acidic phospholipid-binding domains described in full-length SecA proteins (60). The latter domain is needed for the activation of SecA, proper leader peptide-membrane interactions, and the stability of the SecYEG translocase (22), while the SecB protein, which is most likely produced by A. baumannii because of the presence of a canonical secB ortholog in all fully sequenced and annotated strains, plays a critical role as a translocation-specific molecular chaperone (21).

Based on RT-PCR results, which showed the presence of bauD, bauB, and bauA transcripts (Fig. 5), the lack of BauA detection cannot be explained just by the lack of transcription of the bauDCEBA operon either from the bauD promoter, which controls the expression of the entire polycistronic operon, or from the alternative promoter located upstream of bauA (10). We instead propose that the inability of 2010 cells to translocate BauA leads to an initial cytoplasmic accumulation of this protein that results in the immediate degradation of the unfolded precursor as described in E. coli, where abnormal proteins are digested by ATP-dependent proteases (61). Alternatively, the initial BauA intracellular accumulation could abolish the production of this protein by blocking the translation of transcripts initiated at the promoter located immediately upstream of the bauA open reading frame, a possibility that remains to be tested experimentally.

Considering the role SecA plays in the translocation of proteins that are critical for different physiological processes, we predicted that the secA transposon insertion would have a detrimental virulence effect. The fact that the death rate of G. mellonella infected with 2010 bacteria was significantly reduced compared with that of larvae infected with the ATCC 19606T parental strain supports this hypothesis (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the mortality rates caused by the 2010 and t6 insertion mutants, the latter of which does not produce BauA, are indistinguishable. This outcome suggests that the virulence defect of 2010 is mainly due to a failure in iron acquisition via the acinetobactin-mediated transport system, a possibility that is supported by the correction of this defect when the inoculum was supplemented with inorganic iron. Although the secA insertion has the potential to affect different A. baumannii virulence functions, all these observations indicate that the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system is a key virulence factor for this pathogen to establish infection in an invertebrate host that expresses relevant defense mechanisms and presents an iron-limiting environment to infecting bacteria (42, 62).

Because of the role SecA plays in the export of a wide range of proteins, we also predicted that the mutation in the 2010 derivative should have a pleotropic effect on the production of exported proteins involved in different cellular processes. Accordingly, this mutant was affected in the production of proteins playing different physiological roles (Fig. 6A and B). One of the most noticeable effects of the SecA mutation was the impaired production of porins, transporters, and proteins potentially involved in the assembly of outer membrane protein complexes, such as OmpA (Omp38), OmpW, FadL, and YaeT, all of which were associated with the outer membrane fraction (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Changes in the production of some of these proteins, such as OmpW, could be reflected by the inability of 2010 to properly respond to changes in extracellular salt concentrations (Fig. 7). The other most noticeable response to the SecA mutation is the overproduction of stress response proteins, including chaperones and proteins related to oxidative stress. The increased production of HtpG matches the observation that htpG transcription is significantly increased in E. coli harboring a secA(Ts) allele, a regulatory response due to the accumulation of secretory precursor proteins that ultimately activates a σ32-mediated global stress response (63). It is also possible that the purpose of increased production of chaperones such as the trigger factor, DnaK, and GroEL is to handle the stress generated by the reduced production or functioning of SecA, if one considers the role DnaK performs in maintaining transported proteins in an extended export-competent state when bacterial cells contain minimal SecA levels (64). Since the DnaK-mediated translocation process absolutely depends on SecA activity even at low levels (64), these observations provide further support to our hypothesis that the SecA truncated protein produced by 2010 has residual translocation activity. This residual activity could explain not only the reduced presence of outer membrane proteins such as OmpA in this mutant, but also its viability under nonselecting conditions. Specific structural differences between OmpA and BauA could explain the lack of detection of the latter protein in 2010 mutant cells.

The oxidative response involving the overproduction of the AhpC alkyl hydroperoxide reductase C is similar to the response observed in the Bacillus subtilis DB104ΔC mutant, in which the last 22 codons of secA were deleted (65). It is worthy to note the increased production of indolepyruvate decarboxylase in the 2010 mutant compared with the parental strain. This enzyme could be involved in the biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (66), a metabolite we found to be overproduced when A. baumannii ATCC 17978 cells were cultured in the presence of ethanol, which induced a noticeable stress response in addition to significant effects on biofilm biogenesis, motility on semisolid surfaces, and virulence (67). It is also interesting to note that the SecA mutation also resulted in the overproduction of 30S and 50S ribosomal proteins. The biological relevance of this observation is not clear considering that the binding of SecA to the L23 ribosomal protein seems to be the only interaction between this protein and the ribosome that has been described (68). Equally unclear is the apparent association of ribosomal proteins with the outer membrane fraction, a phenomenon we believe is not due solely to fraction contamination since we did not observe it when we used the same experimental approach to study the effect of iron on protein synthesis in the same A. baumannii strain (41). Taken together, our results indicate that although the interruption of the 3′ end of secA in A. baumannii ATCC 19606T is not lethal, it results in a protein homeostatic response to protect cells from different stressors that otherwise could negatively affect overall bacterial viability.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funds from Miami University, NSF 0420479, and Public Health AI44776 grants supported parts of this work.

We thank Marlo Jeffries for her assistance in the transcriptional analysis using qRT-PCR. We are grateful to the Miami University Center of Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics for its support and assistance with automated DNA sequencing and nucleotide sequence analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02925-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis KA, Moran KA, McAllister CK, Gray PJ. 2005. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter extremity infections in soldiers. Emerg Infect Dis 11:1218–1224. doi: 10.3201/1108.050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Shea MK. 2012. Acinetobacter in modern warfare. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villegas MV, Hartstein AI. 2003. Acinetobacter outbreaks, 1977-2000. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 24:284–295. doi: 10.1086/502205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crichton R. 2009. Iron metabolism. From molecular mechanisms to clinical consequences, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM. 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimbler DL, Penwell WF, Gaddy JA, Menke SM, Tomaras AP, Connerly PL, Actis LA. 2009. Iron acquisition functions expressed by the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Biometals 22:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Connerly PL, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH, Actis LA. 2004. The siderophore-mediated iron acquisition systems of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Vibrio anguillarum 775 are structurally and functionally related. Microbiology 150:3657–3667. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mihara K, Tanabe T, Yamakawa Y, Funahashi T, Nakao H, Narimatsu S, Yamamoto S. 2004. Identification and transcriptional organization of a gene cluster involved in biosynthesis and transport of acinetobactin, a siderophore produced by Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T. Microbiology 150:2587–2597. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penwell WF, Arivett BA, Actis LA. 2012. The Acinetobacter baumannii entA gene located outside the acinetobactin cluster is critical for siderophore production, iron acquisition and virulence. PLoS One 7:e36493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natale P, Bruser T, Driessen AJ. 2008. Sec- and Tat-mediated protein secretion across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane—distinct translocases and mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778:1735–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danese PN, Silhavy TJ. 1998. Targeting and assembly of periplasmic and outer-membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet 32:59–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatz PJ, Beckwitz J. 1990. Genetic analysis of protein export in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet 24:215–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.001243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brundage L, Hendrick JP, Schiebel E, Driessen AJ, Wickner W. 1990. The purified E. coli integral membrane protein SecY/E is sufficient for reconstitution of SecA-dependent precursor protein translocation. Cell 62:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90111-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van den Berg B, Clemons WM Jr, Collinson I, Modis Y, Hartmann E, Harrison SC, Rapoport TA. 2004. X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 427:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliver DB, Beckwith J. 1981. E. coli mutant pleiotropically defective in the export of secreted proteins. Cell 25:765–772. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Plessis DJ, Nouwen N, Driessen AJ. 2011. The Sec translocase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:851–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusters I, Driessen AJ. 2011. SecA, a remarkable nanomachine. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:2053–2066. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0681-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driessen AJ. 2001. SecB, a molecular chaperone with two faces. Trends Microbiol 9:193–196. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)01980-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Economou A. 1999. Following the leader: bacterial protein export through the Sec pathway. Trends Microbiol 7:315–320. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rigel NW, Braunstein M. 2008. A new twist on an old pathway—accessory Sec systems. Mol Microbiol 69:291–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meade HM, Long SR, Ruvkum GB, Brown SE, Ausubel FM. 1982. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 149:114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barcak JG, Chandler MS, Redfield RJ, Tomb JF. 1991. Genetic systems in Haemophilus influenzae. Methods Emzymol 204:321–432. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04016-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. 1983. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem 132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. 1985. Improved M13phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2002. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii insertion derivatives generated with a Transposome system. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:6353–6360. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6353-6360.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunger M, Schmucker R, Kishan V, Hillen W. 1990. Analysis and nucleotide sequence of an origin of DNA replication in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its use for Escherichia coli shuttle plasmids. Gene 87:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90494-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnow L. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-tyrosine mixtures. J Biol Chem 118:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwyn B, Neilands JB. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem 160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto S, Okujo N, Sakakibara Y. 1994. Isolation and structure elucidation of acinetobactin, a novel siderophore from Acinetobacter baumannii. Arch Microbiol 162:249–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00301846,10.1007/s002030050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorsey CW, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH, Actis LA. 2003. Genetic organization of an Acinetobacter baumannii chromosomal region harbouring genes related to siderophore biosynthesis and transport. Microbiology 149:1227–1238. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Actis LA, Potter SA, Crosa JH. 1985. Iron-regulated outer membrane protein OM2 of Vibrio anguillarum is encoded by virulence plasmid pJM1. J Bacteriol 161:736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olmsted JB. 1981. Affinity purification of antibodies from diazotized paper blots of heterogeneous protein samples. J Biol Chem 256:11955–11957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gel to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradford M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nwugo CC, Gaddy JA, Zimbler DL, Actis LA. 2011. Deciphering the iron response in Acinetobacter baumannii: a proteomics approach. J Proteomics 74:44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaddy JA, Arivett BA, McConnell MJ, Lopez-Rojas R, Pachon J, Actis LA. 2012. Role of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions in the interaction of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T with human lung epithelial cells, Galleria mellonella caterpillars, and mice. Infect Immun 80:1015–1024. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06279-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaplan EL, Meier P. 1958. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete data. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iacono M, Villa L, Fortini D, Bordoni R, Imperi F, Bonnal RJ, Sicheritz-Ponten T, De Bellis G, Visca P, Cassone A, Carattoli A. 2008. Whole-genome pyrosequencing of an epidemic multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain belonging to the European clone II group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2616–2625. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01643-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, Gerstein M, Snyder M. 2007. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev 21:601–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1510307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vallenet D, Nordmann P, Barbe V, Poirel L, Mangenot S, Bataille E, Dossat C, Gas S, Kreimeyer A, Lenoble P, Oztas S, Poulain J, Segurens B, Robert C, Abergel C, Claverie JM, Raoult D, Medigue C, Weissenbach J, Cruveiller S. 2008. Comparative analysis of Acinetobacters: three genomes for three lifestyles. PLoS One 3:e1805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams MD, Goglin K, Molyneaux N, Hujer KM, Lavender H, Jamison JJ, MacDonald IJ, Martin KM, Russo T, Campagnari AA, Hujer AM, Bonomo RA, Gill SR. 2008. Comparative genome sequence analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 190:8053–8064. doi: 10.1128/JB.00834-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barbe V, Vallenet D, Fonknechten N, Kreimeyer A, Oztas S, Labarre L, Cruveiller S, Robert C, Duprat S, Wincker P, Ornston LN, Weissenbach J, Marliere P, Cohen GN, Medigue C. 2004. Unique features revealed by the genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. ADP1, a versatile and naturally transformation competent bacterium. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5766–5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fournier PE, Vallenet D, Barbe V, Audic S, Ogata H, Poirel L, Richet H, Robert C, Mangenot S, Abergel C, Nordmann P, Weissenbach J, Raoult D, Claverie JM. 2006. Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Genet 2:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaddy JA, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2009. The Acinetobacter baumannii 19606 OmpA protein plays a role in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and the interaction of this pathogen with eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun 77:3150–3160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00096-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez E, Estupinan M, Pastor FI, Busquets M, Diaz P, Manresa A. 2013. Functional characterization of ExFadLO, an outer membrane protein required for exporting oxygenated long-chain fatty acids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochimie 95:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gudmundsdottir A, Bell PE, Lundrigan MD, Bradbeer C, Kadner RJ. 1989. Point mutations in a conserved region (TonB box) of Escherichia coli outer membrane protein BtuB affect vitamin B12 transport. J Bacteriol 171:6526–6533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bearson BL, Bearson SM, Lee IS, Brunelle BW. 2010. The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium QseB response regulator negatively regulates bacterial motility and swine colonization in the absence of the QseC sensor kinase. Microb Pathog 48:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Lorenzo V, Bindereif A, Paw BH, Neilands JB. 1986. Aerobactin biosynthesis and transport genes of plasmid ColV-K30 in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 165:570–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pilsl H, Smajs D, Braun V. 1999. Characterization of colicin S4 and its receptor, OmpW, a minor protein of the Escherichia coli outer membrane. J Bacteriol 181:3578–3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu C, Wang S, Ren H, Lin X, Wu L, Peng X. 2005. Proteomic analysis on the expression of outer membrane proteins of Vibrio alginolyticus at different sodium concentrations. Proteomics 5:3142–3152. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt MG, Oliver DB. 1989. SecA protein autogenously represses its own translation during normal protein secretion in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171:643–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunningham K, Lill R, Crooke E, Rice M, Moore K, Wickner W, Oliver D. 1989. SecA protein, a peripheral protein of the Escherichia coli plasma membrane, is essential for the functional binding and translocation of proOmpA. EMBO J 8:955–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rusch SL, Kendall DA. 2007. Interactions that drive Sec-dependent bacterial protein transport. Biochemistry 46:9665–9673. doi: 10.1021/bi7010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breukink E, Nouwen N, van Raalte A, Mizushima S, Tommassen J, de Kruijff B. 1995. The C terminus of SecA is involved in both lipid binding and SecB binding. J Biol Chem 270:7902–7907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickner S, Maurizi MR, Gottesman S. 1999. Posttranslational quality control: folding, refolding, and degrading proteins. Science 286:1888–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wild J, Walter WA, Gross CA, Altman E. 1993. Accumulation of secretory protein precursors in Escherichia coli induces the heat shock response. J Bacteriol 175:3992–3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qi HY, Hyndman JB, Bernstein HD. 2002. DnaK promotes the selective export of outer membrane protein precursors in SecA-deficient Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 277:51077–51083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Wely KH, Swaving J, Klein M, Freudl R, Driessen AJ. 2000. The carboxyl terminus of the Bacillus subtilis SecA is dispensable for protein secretion and viability. Microbiology 146:2573–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koga J, Adachi T, Hidaka H. 1992. Purification and characterization of indolepyruvate decarboxylase. A novel enzyme for indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Enterobacter cloacae. J Biol Chem 267:15823–15828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nwugo CC, Arivett BA, Zimbler DL, Gaddy JA, Richards AM, Actis LA. 2012. Effect of ethanol on differential protein production and expression of potential virulence functions in the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 7:e51936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karamyshev AL, Johnson AE. 2005. Selective SecA association with signal sequences in ribosome-bound nascent chains: a potential role for SecA in ribosome targeting to the bacterial membrane. J Biol Chem 280:37930–37940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.