Abstract

Previously, we showed that deletion of genes encoding Braun lipoprotein (Lpp) and MsbB attenuated Yersinia pestis CO92 in mouse and rat models of bubonic and pneumonic plague. While Lpp activates Toll-like receptor 2, the MsbB acyltransferase modifies lipopolysaccharide. Here, we deleted the ail gene (encoding the attachment-invasion locus) from wild-type (WT) strain CO92 or its lpp single and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants. While the Δail single mutant was minimally attenuated compared to the WT bacterium in a mouse model of pneumonic plague, the Δlpp Δail double mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were increasingly attenuated, with the latter being unable to kill mice at a 50% lethal dose (LD50) equivalent to 6,800 LD50s of WT CO92. The mutant-infected animals developed balanced TH1- and TH2-based immune responses based on antibody isotyping. The triple mutant was cleared from mouse organs rapidly, with concurrent decreases in the production of various cytokines and histopathological lesions. When surviving animals infected with increasing doses of the triple mutant were subsequently challenged on day 24 with the bioluminescent WT CO92 strain (20 to 28 LD50s), 40 to 70% of the mice survived, with efficient clearing of the invading pathogen, as visualized in real time by in vivo imaging. The rapid clearance of the triple mutant, compared to that of WT CO92, from animals was related to the decreased adherence and invasion of human-derived HeLa and A549 alveolar epithelial cells and to its inability to survive intracellularly in these cells as well as in MH-S murine alveolar and primary human macrophages. An early burst of cytokine production in macrophages elicited by the triple mutant compared to WT CO92 and the mutant's sensitivity to the bactericidal effect of human serum would further augment bacterial clearance. Together, deletion of the ail gene from the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant severely attenuated Y. pestis CO92 to evoke pneumonic plague in a mouse model while retaining the required immunogenicity needed for subsequent protection against infection.

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic yersiniae lead to two types of diseases: yersiniosis (typified by gastroenteritis caused by Yersinia enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis) (1) and plague (evoked by Y. pestis) (2, 3). Y. pestis has evolved from Y. pseudotuberculosis within the last 20,000 years by acquiring additional plasmids and pathogenicity islands as well as by deactivating some genes (4–6). This evolutionary adaptation allowed the plague bacterium to maintain a dual life-style in fleas and rodents/mammals and conferred the ability to survive in the blood instead of the intestine (3). Plague manifests itself in three forms: bubonic (acquired from an infected rodent through a flea bite), pneumonic (acquired either directly by aerosol transmission from an infected host's lungs through respiratory droplets or secondarily from bubonic plague), and septicemic (severe bacteremia either directly due to a flea bite or subsequent to bubonic or pneumonic plague) (2). The latter two forms of plague are almost always fatal without treatment or if the administration of antibiotics is delayed (7, 8). Historically, Y. pestis has been credited for causing three pandemics and >200 million deaths worldwide (2). Currently classified as a reemerging pathogen by the World Health Organization, numbers of Y. pestis outbreaks are increasing with current climate changes and shifting of the rodent carrier range (9). Y. pestis is classified as a tier 1 select agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) due to the ease of weaponizing the organism and its associated high mortality rate in humans (8, 10, 11).

Braun lipoprotein (Lpp) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are the most abundant components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria in the Enterobacteriaceae family, to which Y. pestis belongs (12, 13). Both Lpp and LPS trigger toxic and biological responses in the hosts through the interaction of their lipid domains with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2) and TLR-4, respectively, and by evoking the production of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (14, 15). Also, the complement and coagulation cascades are activated by both Lpp and LPS, and the production of other damaging inflammatory mediators contributes to the severity of infection (14, 16–18).

While Lpp links the peptidoglycan layer to the outer membrane of Y. pestis (19), MsbB is an acyltransferase located in the inner membrane of the bacterial cell wall and catalyzes the addition of lauric acid (C12) to the lipid A moiety of LPS, thus increasing its biological potency (20–23). Y. pestis synthesizes a rough LPS devoid of the O antigen and exists in different acylated forms depending upon bacterial growth temperatures (20, 24–30). For example, lipid A of Y. pestis LPS shifts from a hexa-acylated form at 21°C to 27°C (flea temperature) to a tetra-acylated form at 37°C (human temperature), due in part to the inactivity of MsbB at 37°C, which prevents the activation of TLR-4 (20–23).

Y. pestis must be able to survive in the blood to establish an infection and to increase its chances of transmission, and consequently, the organism must have evolved ways to evade and disarm the host immune system. Ail (attachment-invasion locus), also referred to as OmpX, is a major contributor to serum resistance and complement evasion in Y. pestis (31–34) and accounts for 20 to 30% of the total outer membrane proteins in yersiniae at 37°C (35–37). Ail proteins of Y. enterocolitica and Y. pestis are ∼69% homologous (34) and bind, as well as regulate, several mediators of the complement system, e.g., complement protein 4-binding protein (38–40) and complement factor H (FH) (41–43). In addition to serum resistance, Ail of Y. pestis facilitates the adhesion/invasion of bacteria in host cells (33, 34, 44–46), inhibits inflammatory responses (32, 44), and assists in the translocation of damaging Yersinia outer membrane proteins (Yops) to host cells (44, 45, 47, 48).

In our previous study, we investigated the effects of the deletion of the lpp and msbB genes on the pathogenesis of a highly virulent Y. pestis CO92 strain (49). Both Δlpp single and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants exhibited significant attenuation (70 to 100%) compared to the wild-type (WT) bacterium in pneumonic and bubonic plague mouse models at a dose of 3 50% lethal doses (LD50s) (49). Importantly, only animals initially challenged with the double mutant in a pneumonic plague model were significantly protected (55%) upon subsequent pneumonic infection with 10 LD50s of WT CO92 (49). The attenuated phenotype of the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant in mouse models correlated with its reduced survivability in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages (49). Furthermore, the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant evoked reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines compared to those induced by the WT bacterium in a pneumonic plague mouse model, which coincided with overall decreased dissemination of the mutant to the peripheral organs of mice (49). However, it is important to mention that while the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant was much more impaired in its ability to disseminate than the Δlpp single mutant, substantial numbers of the double mutant bacteria were still detected at the initial infection site (lungs) in some mice at 3 days postinfection (p.i.) (49). Similarly, the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant persisted in the spleen of mice by day 6 p.i. when animals were challenged by the subcutaneous route (49), suggesting the need to delete an additional virulence factor-encoding gene(s) from this Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant to increase attenuation.

It has been reported that the virulence potential of Ail is modulated by the LPS core saccharide length and that Ail's biological activity could be masked by LPS (33). However, since the LPS of Y. pestis lacks O antigen, Ail is believed to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of Y. pestis infections (6). Indeed, a recent study by Kolodziejek et al. showed that Ail of Y. pestis CO92 contributed to virulence in a rat model of pneumonic plague (33). Thus, we aimed to determine whether a deletion of the ail gene from WT CO92 or its Δlpp single and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants would further attenuate the bacterium. Our data showed that the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 was severely attenuated while retaining immunogenicity, thus providing an excellent scaffold from which other virulence genes can be deleted to generate novel live-attenuated vaccine strains for plague in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Y. pestis was grown in heart infusion broth (HIB) (Difco, Voigt Global Distribution Inc., Lawrence, KS) at 28°C with constant agitation (180 rpm). On the solid surface, Y. pestis was grown on either HIB agar or 5% sheep blood agar (SBA) plates (Teknova, Hollister, CA). Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was used for growing recombinant Escherichia coli at 37°C with agitation. Strains containing plasmid pBR322 or its tetracycline-sensitive (Tcs) variant were grown in media with the addition of 100 μg/ml ampicillin. All of our studies were performed in a tier 1 select-agent facility within the Galveston National Laboratory (GNL), University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Advantage cDNA PCR kits were purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA), and all digested plasmid DNA or DNA fragments from agarose gels were purified by using QIAquick kits (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). All tissue culture cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Y. pestis CO92 | ||

| WT | Virulent WT Y. pestis bv. Orientalis strain isolated in 1992 from a fatal pneumonic plague case and naturally resistant to polymyxin B | CDC |

| WT:pBR322 | WT Y. pestis CO92 transformed with pBR322 (Tcs) | 57 |

| WT luc2 | WT Y. pestis integrated with the luciferase gene (luc), used as a reporter strain | 65 |

| Δail | ail in-frame gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | This study |

| Δail:pBR322 | Δail CO92 mutant transformed with pBR322 (Tcs) | This study |

| Δail:pBR322-ail | Δail CO92 mutant complemented with pBR322-ail (Tcs) | This study |

| Δlpp | lpp gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | 55 |

| Δlpp:Tn7-lpp | Δlpp CO92 mutant complemented with lpp in cis by using targeted Tn7 | 60 |

| Δlpp Δail | lpp and ail double gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | This study |

| Δlpp ΔmsbB | lpp and msbB double gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | 49 |

| Δlpp ΔmsbB:pBR322 | Δlpp ΔmsbB CO92 double mutant transformed with pBR322 (Tcs) | This study |

| Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail | lpp, msbB, and ail triple gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | This study |

| Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322 | Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail CO92 triple mutant transformed with pBR322 (Tcs) | This study |

| Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail | Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail CO92 triple mutant complemented with pBR322-ail (Tcs) | This study |

| Δpla | pla in-frame gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | 57 |

| Δcaf1 | caf gene deletion mutant of Y. pestis CO92 | 56 |

| E. coli K-12 DH5α λpir | Strain containing the λpir gene (lysogenized with λpir phage) designed for cloning and propagation of a plasmid with the R6K origin of replication | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDMS197 | Suicide vector with a conditional R6K origin of replication (ori) and a levansucrase gene (sacB) from Bacillus subtilis, used for homologous recombination | 52 |

| pDMS197-Δail | Recombinant plasmid containing the upstream and downstream regions surrounding the ail gene coding region along with the Kmr cassette | This study |

| pKD13 | Template plasmid for PCR amplification of the Kmr gene cassette flanked by FLP recombinase recombination target sites | 51 |

| pFlp2 | Vector that produces the FLP recombinase to remove the Kmr gene cassette from the mutants (Apr) | 50 |

| pBR322 (native) | Cloning vector for complementation (Tcr Apr) | GE Healthcare |

| pBR322 (modified) | Variant of pBR322 (Tcs Apr) | 53 |

| pBR322-ail | Recombinant plasmid containing the ail gene coding region and its putative promoter inserted into the Tcr cassette in vector pBR322, used to complement the Δail mutants of Y. pestis CO92 (Tcs) | This study |

FLP, flippase.

Deletion of the ail gene.

The up- and downstream DNA sequences flanking the ail gene were PCR amplified by using primer pairs Aup5-Aup3 and Adn5-Adn3 (Table 2), respectively, with genomic DNA of Y. pestis CO92 as the template. Additionally, primer pair Km5-Km3 (Table 2), specific for plasmid pKD13, was used to amplify the kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene cassette with flippase (FLP) recombinase recognition sites (50, 51). The upstream DNA fragment flanking the ail gene, the Kmr gene cassette, and the downstream DNA fragment flanking the ail gene were ligated in that order by using appropriate restriction enzyme sites and cloned into the pDMS197 suicide vector (52). The resulting recombinant plasmid, pDMS197-Δail (Table 1), was then transformed into the WT strain, the Δlpp single mutant, and the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant of Y. pestis CO92 via electroporation (Genepulser Xcell; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Transformants were plated onto LB agar plates containing 5% sucrose and 100 μg/ml kanamycin, and Kmr colonies were screened by using PCR to ensure genomic replacement of the ail gene with the antibiotic-resistant cassette. The correct clones were retransformed with plasmid pFlp2, which contains the FLP recombinase, to remove the Kmr gene cassette. Plasmid pFlp2 was eventually cured by growing colonies on 5% sucrose (49), leading to the generation of the single (Δail), double (Δlpp Δail), and triple (Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail) mutants. Subsequent PCR analysis with primer pairs (Up5-Dn3 and Ail5-Ail3) and genomic sequencing with primer SqAil (Table 2) further confirmed the in-frame deletion of the ail gene from all three mutant strains.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of primers used in this study

| Primer pair or primer | Primer sequence (5′–3′) (restriction enzyme)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Aup5-Aup3 | TATGAGCTCACGACGCACAAGACTCTGGC (SacI)-AACGGATCCCCATCCAGATTGTTATAAC (BamHI) | PCR amplification of the upstream DNA fragment flanking the ail gene of Y. pestis CO92 |

| Adn5-Adn3 | ATGAAGCTTCCTAACGTCCTCCTAACCATG (HindIII)-GCATCCGTCAATGGTACCAG (KpnI) | PCR amplification of the downstream DNA fragment flanking the ail gene of Y. pestis CO92 |

| Km5-Km3 | ATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC (BamHI)-CTTAAGCTTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC (HindIII) | PCR amplification of the Kmr gene cassette with FLP recombinase recognition target sites from plasmid pKD13 at both ends |

| Up5-Dn3 | ATGCCCACATCGTTACCACC-CCGTAATCCATGGTGATCTG | ail mutant verification primers located outside the flanking DNA sequences of the ail gene on the chromosome that were used for generating the ail mutants of Y. pestis CO92 |

| Ail5-Ail3 | TAATGTGTATGCCGAAGGC-TTGGAGTATTCATATGAAGC | PCR amplification of the coding region of the ail gene from Y. pestis CO92 |

| Apbr5-Apbr3 | CGGGATCCCGCAAGGTCAATGGGGCTATTG (BamHI)-ACGCGTCGACTTAGAACCGGTAACCCGCGC (SalI) | PCR amplification of the ail gene of Y. pestis CO92 including its promoter for integration into the pBR322 vector for complementation |

| SqAil | GGAATACTGTACGAATATCC | Primer located 108 bp upstream of the ail gene; used to confirm the in-frame deletion of the ail gene by chromosomal DNA sequencing |

Underlining indicates restriction enzyme sites.

Complementation of the Δail mutant strains of Y. pestis CO92.

By using primers Apbr5-Apbr3 (Table 2), the coding region of the ail gene with its promoter was PCR amplified with genomic DNA of WT CO92 as the template. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the pBR322 vector, creating recombinant plasmid pBR322-ail (Table 1). Through electroporation, plasmid pBR322-ail was transformed into the Δail single and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strains, resulting in the creation of the complemented Δail:pBR322-ail and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail Y. pestis strains (Table 1). These complemented strains were sensitive to tetracycline due to the replacement of a large portion of the tetracycline resistance (Tcr) cassette from plasmid pBR322 with the ail gene. The Tcs variant of the pBR322 vector (53) without the ail gene was also electroporated into WT CO92 and the Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutants for generating empty vector controls (e.g., WT:pBR322, Δail:pBR322, Δlpp ΔmsbB:pBR322, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322, respectively) (Table 1).

Absence of Ail and unchanged levels of Lpp in the membranes of Y. pestis CO92 Δail mutants.

The generated mutant strains were grown overnight in HIB medium at 28°C with shaking at 180 rpm, and the resulting bacterial cell pellets (representing similar CFU) were dissolved by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. An aliquot of the samples was then analyzed by immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies to Ail and monoclonal antibodies to Lpp that were available in the laboratory (54, 55). As a loading control for the Western blots, the presence of DnaK in the bacterial pellets of the mutants and WT CO92 was assessed by using anti-DnaK monoclonal antibodies (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY).

Growth kinetics and membrane alteration of the Y. pestis CO92 triple mutant.

WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were grown in 100 ml of HIB medium contained in 500-ml HEPA filter Top polycarbonate Erlenmeyer culture flasks (Triforest Labware, Irvine, CA) at 28°C with constant shaking (180 rpm). Samples from each flask were taken at 1- to 2-h intervals until the cultures reached their plateau phases. CFU were determined by plating (56). For visualization of membrane alterations, bacterial strains were grown to exponential phase at 28°C (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.6). The cells were washed, pelleted, fixed, and subjected to transmission electron microscopy (57).

Sensitivity of the Y. pestis CO92 mutants to gentamicin.

The MICs of gentamicin against WT Y. pestis CO92:pBR322 and the Δail:pBR322, Δail::pBR322-ail, Δlpp ΔmsbB:pBR322, Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail mutants were determined by an Etest (bioMérieux Inc., Durham, NC) (49). Briefly, the bacterial cultures were spread evenly onto 5% SBA and LB agar plates, and predefined gentamicin (range, 0.016 to 256 μg/ml) Etest strips were placed onto the plates. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 28°C, and the MICs were recorded.

Evaluation of essential Y. pestis virulence factors in various mutants of Y. pestis CO92.

The intactness and functionality of the type 3 secretion system (T3SS), crucial for plague pathogenesis and immunity, were then evaluated. Through the T3SS, the plague bacterium secretes Yops such as YopE, YopH, and LcrV (low-calcium-response V antigen) in response to a low-calcium signal. Consequently, WT CO92 and Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:20 and grown in either HIB or calcium-depleted modified M9 medium (42 mM Na2HPO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, 8.6 mM NaCl, 18.6 mM NH4Cl, 0.001 mg/ml FeSO4, 0.0001% thiamine, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.4% dextrose, and 1% Casamino Acids) at 28°C with shaking (180 rpm) for 3 h and then at 37°C for 2 h.

When the bacteria were grown in HIB, 5 mM EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to trigger the low-calcium response 5 min before harvesting of the cultures. Aliquots of the cultures grown in either medium (representing similar CFU) were removed, and 1 ml of the supernatants was precipitated with 55 μl of 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) on ice for 2 h. The TCA precipitates were dissolved in SDS-PAGE buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to YopE, LcrV (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and YopH (Agrisera, Stockholm, Sweden) (49, 55, 57). The anti-DnaK monoclonal antibody (Enzo) was employed to probe bacterial pellets to ensure that the bacterial supernatants were obtained from similar numbers of bacteria across the tested strains.

To evaluate the translocation of T3SS effectors by the Y. pestis mutants, a digitonin extraction assay was used (55). Briefly, Y. pestis cultures grown overnight in HIB were diluted in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The diluted bacteria were cultivated at 28°C for 30 min and then at 37°C for 60 min. HeLa cells (in a 12-well plate) were then infected with the above-described Y. pestis cultures at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30. After 4 h of infection at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with 200 μl of digitonin (1% in PBS). The cells were dislodged from the surface of the plate, collected, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min to obtain the supernatant and the pellet fractions. The YopE polyclonal antibodies were then used to detect YopE in both the fractions, while antiactin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-DnaK monoclonal antibodies were employed for the supernatant and pellet fractions, respectively, to monitor equivalent sample loading during Western blot analyses.

For examining capsular antigen (F1) production by WT CO92 and its triple mutant, bacteria grown at 37°C were subjected to a commercially available plague detection kit, the Yersinia pestis (F1) Tetracore RedLine Alert kit (Tetracore, Rockville, MD), as we previously described (56). A Δcaf1-negative mutant of CO92 devoid of F1 antigen was used as a control (56). We further analyzed F1 production by WT CO92 and its triple mutant by flow cytometry (56). Briefly, the above-mentioned Y. pestis cultures (106 CFU/sample) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After being washed with PBS, the bacteria were incubated with a primary antibody to the F1 antigen (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by a secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG1) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. The bacterial cells were then washed and resuspended in 500 μl of fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (1% FBS in PBS) before analysis. Samples were read on an LSRII Fortessa instrument (UTMB Core Facility) and analyzed with FlowJo software. We also examined F1 production by WT CO92, the Δcaf1-negative mutant, and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant by immunofluorescence (IF) staining using anti-F1 antibodies and microscopy (56).

The Pla (plasminogen activator) surface protease of Y. pestis is a multifunctional protein that contributes to bacterial adherence to host cells, intracellular survival, complement resistance, and bacterial dissemination by virtue of possessing fibrinolytic and coagulase activities (48, 57–63). To examine whether the deletion of three membrane protein-encoding genes (lpp, msbB, and ail) from WT CO92 altered Pla levels, we performed Western blot analysis. The various Y. pestis strains grown overnight were diluted 1:20 in fresh HIB and grown at 28°C with shaking (180 rpm) for 3 h and then at 37°C for 2 h. The bacterial cell pellets were harvested and dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. An aliquot of the samples was then analyzed by immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies to Pla that were available in the laboratory (54). The anti-DnaK monoclonal antibody was also employed to monitor equivalent sample loading during Western blot analyses.

To ensure that Pla was properly displayed on the bacterial surface and enzymatically active, we measured its protease activity by using a fluorimetric assay with the Pla substrate (64). Briefly, all of the tested strains were plated onto HIB agar plates at 28°C for 36 h. The strains were then replated onto fresh HIB agar plates and incubated at either 28°C or 37°C (representing flea and human body temperatures, respectively) for 20 to 22 h. Bacteria from each plate were suspended in PBS and adjusted to optical densities (OD600) of 0.1 (5 × 107 CFU/ml) and 0.5 (2.5 × 108 CFU/ml) by using a Bio-Rad SmartSpec 300 instrument. For each strain, 50 μl of the suspension was added to the wells of a black microtiter plate (Costar Corning Inc., Corning, NY) in triplicate. The hexapeptide substrate 4-{[4′-(dimethylamino)phenyl]azo}benzoic acid (DABCYL)-Arg-Arg-Ile-Asn-Arg-Glu{5-[(2′-aminoethyl)amino]naphthalene sulphonic acid (EDANS)}-NH2, at a final concentration of 2.5 μg/well, was added to the bacterial cells. The kinetics of substrate cleavage by Pla displayed on the bacterial surface was measured every 15 min for 2 h by a fluorimetric assay (extinction/emission wavelength of 360 nm/460 nm) at 37°C by using a BioTek Synergy HT spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT).

Animal studies with the Y. pestis CO92 mutant strains.

Six- to eight-week-old female Swiss Webster mice (17 to 20 g) were purchased from Taconic Laboratories (Germantown, NY). All of the animal studies were performed in an animal biosafety level 3 (ABSL-3) facility under an approved UTMB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. Mice were challenged intranasally (i.n.) with 1.3 × 104 CFU (representing 26 50% lethal doses [LD50s] of the WT bacterium, with 1 LD50 corresponding to 500 CFU [57]) of WT CO92 or the Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB or Δlpp Δail double, or Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain. Also, the animals were challenged by the i.n. route with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant at higher doses of 4.0 × 104, 1.7 × 105, 5.9 × 105, 1.8 × 106, and 3.4 × 106 CFU (corresponding to 80, 340, 1,180, 3,600, and 6,800 LD50s of WT CO92). Mice were assessed for morbidity and/or mortality as well as clinical symptoms over the duration of each experiment (24 to 30 days p.i.).

Survivors after initial infection with the mutants were subsequently challenged with 1 × 104 to 1.4 × 104 CFU (20 to 28 LD50s) of the bioluminescent WT Y. pestis CO92 luc2 strain (65), which contains the luciferase (luc) gene and its substrate, allowing in vivo imaging of mice in terms of bacterial dissemination in real time. Naive mice of the same age and infected with the WT CO92 luc2 strain were used as controls. On day 3 and/or day 7 p.i., the animals were imaged by using an Ivis 200 bioluminescence and fluorescence whole-body imaging workstation (Caliper Corp., Alameda, CA) in the ABSL-3 facility.

Bacterial dissemination and histopathological studies of the triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92.

Mice infected with 2.5 × 106 CFU (representing 5,000 LD50s of WT CO92) of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant or WT CO92 by the i.n. route were euthanized by using a mixture of ketamine and xylazine, followed by cervical dislocation on days 2, 3, and 6 p.i. For each time point, five mice per group were used, and the lungs, liver, and spleen were removed immediately following animal sacrifice. Blood was collected from these animals by cardiac puncture. The tissues were homogenized in 1 ml of PBS, and serial dilutions of the homogenates were spread onto SBA plates to assess dissemination of the bacteria to peripheral organs (49).

Portions of each organ (lung, liver, and spleen) from 5 mice at each time point were also removed and immersion fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (55, 60). The tissues were processed and sectioned at 5 μm, and the samples were mounted onto slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Tissue lesions were scored on the basis of a severity scale, which correlated with estimates of lesion distribution and the extent of tissue involvement (minimal, 2 to 10%; mild, >10 to 20%; moderate, >20 to 50%; severe, >50%), as previously described (55, 60). The histopathological evaluation of the tissue sections was performed in a blind fashion.

Cytokine and chemokine levels and antibody responses in mice infected with the triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92.

Concurrently, blood was collected from infected (with WT CO92 versus the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant) animals on days 2, 3, and 6 p.i. (for cytokine analysis). Blood was also collected from all animals prior to infection and on day 14 p.i. to determine antibody responses. Serum samples were filtered by using Costar 0.1-μm centrifuge tube filters (Corning Inc.). The levels of cytokines/chemokines, namely, IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and TNF-α, in sterile serum samples were analyzed by using a mouse 6-plex Bioplex assay (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

Total levels of IgG and antibody isotypes in the sera of animals infected with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were determined at 14 days p.i. by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with either the F1-V fusion protein (1 ng/ml; BEI Resources, Manassas, VA) or whole bacterial cells of WT CO92 overnight at 4°C. For the whole-bacterial-cell ELISA, microtiter plates were first coated with poly-l-lysine (10 μg/ml), as we previously described (66).

The sera were serially diluted (either 1:5 or 1:10), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to determine total IgG titers and IgG isotype responses by employing goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, IgG1-HRP, IgG2a-HRP, and IgG2b-HRP (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). The substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) was used for color development, and the plates were read at 450 nm by using a spectrophotometer (66).

Serum resistance of various mutants of Y. pestis CO92.

Normal human and mouse sera were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and nonhuman primate (NHP) sera were collected from naive animals that were housed at the GNL. Prior to use, an aliquot of each serum sample was also heated at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate complement and served as a control. WT CO92:pBR322, Δail:pBR322, Δlpp ΔmsbB:pBR322, Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322, Δail:pBR322-ail, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail strains were grown overnight, harvested, and then diluted in PBS to an OD600 of 0.8 (∼4 × 108 CFU/ml). A 50-μl volume of the diluted bacteria (∼2 × 107 CFU) was mixed with 200 μl of either normal (unheated) or heated sera. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with shaking at 500 rpm. The number of surviving bacteria (CFU) in each sample was determined by serial dilutions and plating onto SBA plates (49, 57). Percent bacterial survival was calculated by dividing the average number of CFU in samples incubated in normal serum by the average number of CFU in samples incubated in heat-inactivated serum and multiplying by 100.

Adherence, invasion, and intracellular survival of various Y. pestis CO92 mutants in HeLa and A549 epithelial cells.

Twelve-well tissue culture plates were seeded with either HeLa (from human cervix) or A549 (human alveolar) epithelial cells at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells in 1 ml of DMEM, 10% FBS (HeLa) or F-12K (Kaighn's) medium, and 10% FBS (A549) (61, 67). The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 until a confluent monolayer was established.

Bacterial strains grown overnight were used to infect host cells at an MOI of 100. The plates were centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 10 min to ensure bacterial contact with the host cells. After 2 h of incubation, one set of the triplicate wells was not washed, and the total numbers of bacteria used for infection that were present in the culture medium and those adhering to and/or invading the host cells were recovered by scraping and vortexing the host cells. Another set of triplicate wells was gently washed twice with 1 ml of Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and the adherent and invading bacteria in the host cells were then enumerated after lysing epithelial cells with 1 ml of ice-cold water.

The last set of the host cells was similarly washed twice with DPBS, and a gentamicin (50 μg/ml) protection assay was used to discriminate between invading and extracellular bacteria (61). After 1 h of incubation in gentamicin-containing medium to kill extracellular bacteria, the host cells were washed twice with 1 ml of DPBS, and intracellular bacteria were then enumerated after the addition of 1 ml of ice-cold water to each well (61). The percentages of invasion and adhesion were then determined.

The intracellular survival of various CO92 mutants in HeLa and A549 cells was assessed in a manner similar to that described above for the invasion assay. The 0-h samples corresponded to a time point immediately after gentamicin treatment. The intracellular bacteria in HeLa and A549 cells were then enumerated by serial dilution and plating after 12 h of incubation in medium containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin (55).

Survival of WT Y. pestis CO92 and its mutant strains in murine alveolar macrophages and human monocyte-derived macrophages and production of cytokines.

Murine MH-S alveolar macrophages were infected with WT CO92 and its mutant strains at an MOI of 10. After 30 min of infection, the host cells were treated for 45 min with 20 μg/ml gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. The surviving bacteria inside the macrophages were then enumerated immediately after gentamicin treatment (0-h time point) and subsequently at 2 and 4 h of incubation in medium containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin. The number of bacteria present inside the macrophages was determined by serial dilution and plating (55).

Human buffy coats were obtained from three different healthy individuals in 10-ml Vacutainer tubes without additive (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) from the UTMB blood bank. The EDTA-treated blood was handled under endotoxin-free conditions and diluted 1:1 with PBS, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified by centrifugation over a Ficoll-sodium diatrizoate solution (Ficoll-Paque Plus; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Monocytes were then purified from PBMCs by positive selection using human CD14 microbeads and a magnetic column separation system from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Monocyte-derived macrophages were subsequently differentiated from purified CD14+ monocytes.

Briefly, monocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, HEPES, sodium pyruvate, penicillin-streptomycin, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (100 ng/ml) (Leukine [sargramostim]; Genzyme Corp., Cambridge, MA). Monocytes were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates at 106 cells/ml, and adherent monocyte-derived macrophages were obtained at 6 days of culture.

These human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs) were infected with WT CO92 and its mutant strains at an MOI of 1. The infected macrophages were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 45 min, followed by 1 h of treatment with 10 μg/ml gentamicin. The surviving bacteria inside the macrophages were enumerated immediately after gentamicin treatment (0-h time point) and subsequently at 2 h and 4 h (55). The concentration of gentamicin used in the gentamicin protection assay was optimized for each host cell type used in this study.

Supernatants from infected macrophages during the intracellular survival assay were collected at each of the time points tested and filtered. A Bio-Rad mouse 6-plex assay kit (IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-17, IL-6, and TNF-α) or a Bio-Rad human 8-plex assay kit (GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α) was used to measure cytokine and chemokine levels.

Statistical analysis.

For the majority of the experiments, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used with the Bonferroni correction, except for the intracellular survival experiments, in which Tukey's post hoc test was employed for data analysis. We used Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for animal studies, and P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant for all of the statistical tests used.

RESULTS

In vitro characterization of Δail mutants of Y. pestis CO92.

The in-frame deletion of the ail gene from WT CO92 and the Δlpp single and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants of Y. pestis CO92 was confirmed by PCR analysis using specific primers (Table 2) as well as by DNA sequencing of the flanking regions of the ail gene on the chromosome. The above-mentioned genetic manipulations resulted in the creation of authentic Δail single, Δlpp Δail double, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutants of Y. pestis CO92. As shown in Fig. 1A, Ail-specific antibodies detected the correct-sized protein in WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant but not in the Δail single, Δlpp Δail double, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple isogenic mutants. Importantly, deletion of the ail gene from WT CO92 did not affect the production of Lpp (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Ail and Lpp production and transmission electron microscopy analysis. (A) Y. pestis cultures grown overnight (at 37°C) were collected, and the production of Ail and Lpp in the whole-cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to Ail and Lpp. Anti-DnaK antibodies were used as a loading control for Western blots. (B) WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were grown to the exponential growth phase at 28°C and subjected to transmission electron microscopy analysis. o, bacterial outer membrane; i, bacterial inner membrane; p, periplasmic space. Bar = 0.5 μm.

Since both Ail and Lpp are outer membrane proteins and the MsbB acyltransferase modifies LPS, WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were subjected to transmission electron microscopy to evaluate if there were any membrane alterations. Except for finding that the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant had somewhat decreased periplasmic space compared to that of WT CO92 (Fig. 1B), no other abnormalities were apparent. The growth kinetics of the triple mutant was also examined, and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant entered log phase at an earlier time point and grew faster initially than did WT CO92; however, both strains had similar CFU by 16 h (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 produces essential Y. pestis virulence and immunogenic factors.

The T3SS is an essential virulence mechanism in Y. pestis. Through the T3SS, an immunoreactive antigen (LcrV) as well as other Yops such as YopE and YopH (which destroy actin monofilaments and interfere with phagocyte signal transduction machinery, respectively) are secreted. Therefore, T3SS-dependent protein secretion in response to a low-calcium signal was measured for the generated ail mutants. This in vitro assay mimics the environment during eukaryotic host cell contact with the bacterial T3SS needles. In calcium-depleted M9 medium, the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant showed significantly increased levels of YopH and YopE in the culture supernatants compared to those of WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant (Fig. 2A). While an increased level of YopH in the supernatant of the Δail single mutant was also noted, the YopE level in the culture medium was not as pronounced as those of the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant and WT CO92 (Fig. 2A). There was no significant difference in the levels of LcrV in the culture supernatants across the strains tested (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Functionality of the T3SS and production/enzymatic activity of the Pla protease. Cultures of various Y. pestis strains grown in HIB overnight were diluted 1:20 in modified M9 medium or fresh HIB, and growth was continued at 28°C for 3 h, followed by an additional 2 h of incubation at 37°C. (A and B) The production of YopH, LcrV, and YopE in M9 medium (A) or YopH in HIB chelated for calcium (B) was measured by Western blotting using specific antibodies. Anti-DnaK antibodies were employed to examine bacterial pellets to ensure that bacterial supernatants were obtained from similar numbers of bacteria across the tested strains. For the translocation studies, cultures of various Y. pestis strains grown overnight in HIB were diluted and sensitized to DMEM by growth at 28°C for 30 min, followed by an additional 1 h of incubation at 37°C. HeLa cells were then infected with the above-mentioned cultures at an MOI of 30. (C) After 4 h of infection, the cytosolic fraction of the host cells was separated from the pellet and probed with anti-YopE antibodies. Antiactin and anti-DnaK antibodies were also used on the supernatant and pellet fractions, respectively, to monitor equal loading of the samples during Western blot analyses. (D) Pla production in various Y. pestis CO92 stains was examined with specific antibodies to Pla, and anti-DnaK antibodies were used as a loading control. For measurement of Pla activity, the tested Y. pestis CO92 strains were mixed with the Pla substrate [DABCYL-Arg-Arg-Ile-Asn-Arg-Glu(EDANS)-NH2], and the kinetics of substrate cleavage was measured. The Δpla single mutant of CO92 was employed as a negative control during the assay. (E) The kinetics of each reaction is plotted as arithmetic means ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis of Pla activity data was performed by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistically significant P values between the groups are indicated by a vertical line.

To demonstrate that the higher level of the specific effector YopH observed in the culture supernatant of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (Fig. 2A) was not due to the leakiness of the bacterial cell membrane and the T3SS itself, we examined the secretion of YopH by the triple mutant grown in HIB medium after induction of a low-calcium signal. As shown in Fig. 2B, 5 min after the addition of EGTA, YopH was detected in the supernatants of WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant; however, no detectable level of YopH was present in uninduced culture supernatants (data not shown). Importantly, compared to the WT bacterium, there was a significant increase in the level of YopH in the supernatant of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (Fig. 2B).

To simulate in vivo conditions and to measure the translocation of Yops, HeLa cells were infected with various mutant strains of Y. pestis. A digitonin extraction assay was used to evaluate the translocation of YopE into the host cells. While WT CO92 and Δlpp ΔmsbB mutant bacteria had similar levels of YopE translocation, the ail deletion mutants (both Δail and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail) had significantly decreased translocation of YopE into the cytosol of the host cells (Fig. 2C). YopE translocation was restored in the ail deletion mutants when complemented with the corresponding gene in trans (Fig. 2C). The decreased level of YopE translocation from the ail deletion mutants was not due to differential expression of the yopE gene or the number of bacteria that were used to infect HeLa cells, as all of the strains had similar levels of YopE and DnaK in the cell pellet fraction (Fig. 2C).

Pla, another important virulence factor of Y. pestis, is a multifunctional protein (48, 57–61). To evaluate whether the levels of Pla remained unaltered in the Δail mutants, Western blot analysis was performed. Essentially, similar levels of the Pla protein were noted for the various mutant strains tested (Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple, as well as ail-complemented mutant strains) compared to that of WT CO92 at 37°C, a temperature that increases Pla production and activity (36, 68, 69) (Fig. 2D). To confirm the Western blot data and to ensure that Pla activity was fully retained by the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant compared to WT CO92, the mutant bacteria were exposed to a fluorogenic hexapeptide Pla substrate. This substrate was selected from the library of fluorogenic peptides by positional screening methods (64). Both WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant cleaved the substrate in a time-dependent manner following essentially similar kinetics at both 28°C and 37°C at the two tested bacterial concentrations (Fig. 2E). As a control, a Pla-negative mutant (Δpla) of CO92 did not cleave the substrate.

Not only is the capsular antigen (F1) a major immunoreactive protein of Y. pestis, it also exhibits antiphagocytic properties (70). Thus, F1 production was verified in WT CO92 versus its triple mutant by using a commercially available plague immunochromatographic dipstick (impregnated with F1 antibodies) test, which allows rapid, in vitro qualitative identification of Y. pestis. Both WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant produced purple bands in the reaction and control lanes of similar intensities, whereas the Δcaf1 mutant (negative control) was positive only in the control lane (Fig. 3A). To confirm these results, the presence of F1 on bacterial cells was verified by IF staining with F1-specific antibodies, followed by flow cytometry and microscopy (56). As shown in Fig. 3B and C, F1 was detected on the surfaces of both WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant, while the Δcaf1 mutant was negative for the presence of F1.

FIG 3.

Production of F1 antigen. Selected Y. pestis cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:20 in fresh HIB, and growth was continued at 28°C for 3 h, followed by an additional 2 h of incubation at 37°C. F1 production was either examined by using immunochromatographic reaction dipsticks (A) or probed by immunofluorescence staining with anti-F1 antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis (B) and microscopy (C). The Δcaf1 mutant of CO92 was employed as a negative control. Magnification, ×400 (C). FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Evaluation of Y. pestis CO92 Δail mutants in a pneumonic plague mouse model.

To gauge the virulence potential of the Δail mutant strains, mice (n = 10/group) were infected by the i.n. route with similar doses (1.3 × 104 CFU, representing 26 LD50s of the WT bacterium) of the Δail single, Δlpp Δail or Δlpp ΔmsbB double, or Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain as well as WT CO92. While animals inoculated with WT CO92 died by day 4 p.i., all of the mice infected with the Δail single mutant died by day 10 p.i., showing an increased mean time to death (Fig. 4A), confirming data from a previous report by Kolodziejek et al. (33). Mice infected with the Δlpp Δail and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant had increased survival rates (20, 40, and 100%, respectively). Clinically, animals infected with WT CO92 or mutants that provided minimal attenuation in mice had ruffled fur, hunched back, and lethargy, and they were unable to groom and tended to huddle together.

FIG 4.

Survival analysis and antibody responses of mice infected with WT Y. pestis strain CO92 and its mutant strains in a pneumonic plague model. Female Swiss Webster mice (10 per group) were challenged with 1.3 × 104 CFU of WT Y. pestis strain CO92 or its various mutants by the i.n. route. (A) Survival of mice was plotted and analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. Statistically significant P values for comparisons of various mutant- and WT CO92-infected mice are indicated under each curve. (B) Mice were bled at 14 days p.i., and the total IgG responses to F1-V antigen were determined by an ELISA. The arithmetic means ± standard deviations are plotted. ** indicates statistical significance (P < 0.001) compared to preimmune serum.

To evaluate the specific immunity to Y. pestis that developed, sera from all of the surviving mice infected with various mutants of CO92 (Fig. 4A) were collected on day 14 p.i. Animals challenged with WT CO92 or the Δail single mutant could not be bled, since there were no survivors. Based on the ELISA data, sera from mice challenged with the Δlpp ΔmsbB and Δlpp Δail double mutants exhibited high total IgG titers (1:3,125) to the F1-V antigen (Fig. 4B), while this titer was low (1:25) when animals were infected with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (Fig. 4B).

The extent of attenuation of the virulence potential of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant was then ascertained by infecting mice by the i.n. route with increasing doses ranging from 4.0 × 104 to 5.9 × 105 CFU, representing 80 to 1,180 LD50s of the WT bacterium (Fig. 5A). A group of animals that received 32 LD50s of WT CO92 served as a control, and all of them died by day 4 p.i. The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant was unable to kill mice at all of these doses and thus resulted in 100% survival rates (Fig. 5A). Importantly, the total IgG titers (on day 14 p.i.) in the sera progressively increased (up to 1:625) when the animals were challenged with increasing doses (80 to 1,180 LD50s of WT CO92) of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Virulence potential of and subsequent protection conferred by the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 in a pneumonic plague mouse model. (A) Female Swiss Webster mice (n = 9 or 10/group) were challenged with the indicated doses of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant or 1.6 × 104 CFU of WT Y. pestis CO92 by the i.n. route. The surviving animals and age-matched naive mice were then rechallenged on day 24 p.i. with 1 × 104 CFU of the WT CO92 luc2 strain. Statistically significant P values are for comparisons to WT CO92-infected mice during the initial challenge or to naive control animals during WT CO92 luc2 rechallenge. (B) Total IgG responses to the F1-V antigen were examined in sera at day 14 after initial infection. ** indicates statistical significance (P < 0.001) compared to preimmune serum or between different doses of the triple mutant used for initial infection. (C) The animals after rechallenge were imaged at 72 h for bioluminescence. The bioluminescence scale is shown at the right and ranges from most intense (red) to least intense (violet). The animal on the left of each imaging panel represents an uninfected control.

To further assess the specific immunity induced in mice after initial infection with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain (Fig. 5A), the surviving animals were subsequently challenged on day 24 p.i. with 1.0 × 104 CFU (20 LD50s) of the WT CO92 luc2 strain. Age-matched naive mice were used as a control, and 90% of them died by day 4 p.i. (Fig. 5A). There was an increase in the time to death and somewhat of a dose-dependent protection, which was maximal in animals that were initially infected with 5.9 × 105 CFU (1,180 LD50s of WT CO92) of the triple mutant (50% of the mice survived) compared to naive animals during the WT CO92 luc2 strain rechallenge (Fig. 5A).

The surviving mice were imaged on day 3 p.i. by using an in vivo imaging system, and the first animal on the left in each imaging panel was uninfected and served as a control (Fig. 5C). While the WT CO92 luc2 strain disseminated to the whole body in 6 out of 9 naive animals (Fig. 5CI), the bioluminescent strain was confined to the initial infection site (lungs) in animals that were first infected with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant before being challenged with the WT CO92 luc2 strain (Fig. 5CII to IV). As the dose of the initial infection with the triple mutant was increased from 4 × 104 to 1.7 × 105 CFU, the number of animals that were positive for bioluminescence decreased from 6/10 to 4/10 animals subsequent to WT CO92 luc2 strain challenge (Fig. 5CII and III). At the highest infection dose of the triple mutant (5.9 × 105 CFU), only 2/10 mice were positive for bioluminescence as a result of subsequent CO92 luc2 challenge, with 80%, 60%, and 50% of the animals surviving on days 7, 8, and 10, respectively (Fig. 5A). Since half of the animals did not succumb to infection, these data indicated clearing of the WT CO92 luc2 strain (Fig. 5CIV).

In our subsequent experiment, initial infection doses of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant given to the mice i.n. were increased to 1.8 × 106 and 3.4 × 106 CFU, which corresponded to 3,600 and 6,800 LD50s of WT CO92, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6A, even the highest dose of the triple mutant was unable to kill mice, while the control animals infected with a much lower dose of WT CO92 (26 LD50s) died by day 4 (Fig. 6A). As expected, in the sera of mice infected with the highest challenge dose (3.4 × 106 CFU) of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain, the total IgG and IgG isotype (IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b) antibody titers to F1-V antigen were sustained at 1:625 (Fig. 6B), indicating balanced TH1 and TH2 responses. The total IgG titers were higher (1:1,000) when the ELISA plates were coated with whole cells and reflected the presence of antibodies to other Y. pestis antigens along with F1 and V (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

Survival analysis and subsequent protection conferred by high doses of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 in a pneumonic plague mouse model. (A) Female Swiss Webster mice (5 to 10 per group) were infected with various doses of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant or 1.3 × 104 CFU of WT Y. pestis CO92 by the i.n. route. Surviving mice with age-matched naive animals were then rechallenged on day 24 p.i. with 1.4 × 104 CFU of the WT CO92 luc2 strain. Statistically significant P values are for comparisons to the WT CO92-infected mice in the initial challenge or to naive control mice during the WT CO92 luc2 rechallenge. (B) Total IgG responses to the F1-V antigen or whole bacteria were examined in sera at day 14 after initial infection. The titers of antibody isotypes to F1-V antigen were further delineated by using isotype-specific secondary antibodies. *** indicates statistical significance (P < 0.0001) compared to preimmune serum. (C) Animals were imaged on day 3 and/or day 7 after rechallenge for bioluminescence. The bioluminescence scale is shown on the right and ranges from most intense (red) to least intense (violet).

As expected, protection levels increased to 70% when the animals were initially infected with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant at a dose of 3.4 × 106 CFU (6,800 LD50s of WT CO92) and then challenged i.n. on day 24 with a higher dose (28 LD50s or 1.4 × 104 CFU) of the WT CO92 luc2 strain (Fig. 6A). Mice (n = 5 to 10) were again imaged with the in vivo imaging system (Fig. 6C). On day 3 postchallenge, 5/5 naive animals were positive for bioluminescence, while the WT CO92 luc2 strain disseminated throughout the animal bodies of 4/5 mice (Fig. 6CI). Only 2 of the 10 animals that had received the triple mutant at the highest dose before being challenged with the WT CO92 luc2 strain were positive for bioluminescence (Fig. 6CII), and these animals subsequently died by day 6 (Fig. 6A). On day 7 p.i., another mouse succumbed to infection and was positive for bioluminescence (Fig. 6CIII). The low level of bioluminescence detected in the dead animal was possibly due to a lack of oxygen and a low body temperature that diminished bioluminescence (65). Importantly, the remaining 7 mice that were previously infected with 3.4 × 106 CFU of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were devoid of bioluminescence after subsequent challenge with the WT CO92 luc2 strain, indicating clearance of the infecting pathogen (Fig. 6CIII). Collectively, these data suggested that the increased humoral immune response generated by the triple mutant in mice seemed to correlate with the subsequent enhanced protection of animals when challenged with WT CO92.

Bacterial dissemination and histopathological lesions in mice challenged with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 by the intranasal route.

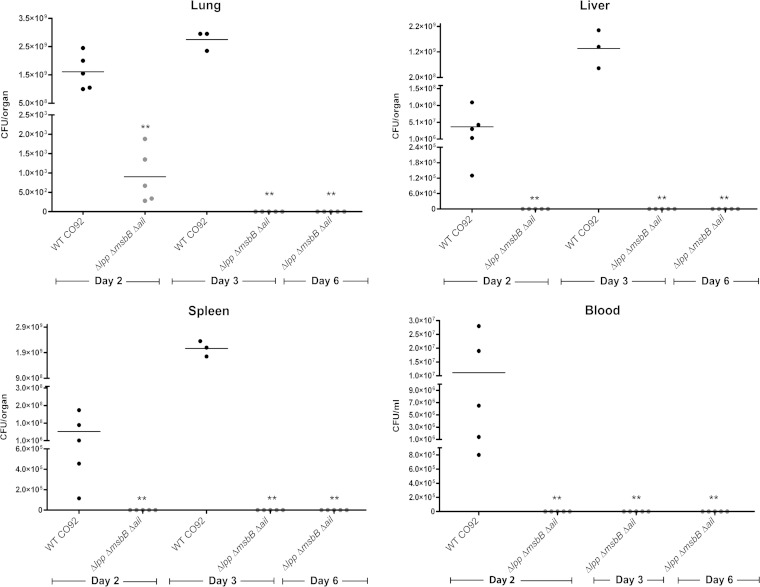

Mice were challenged with 2.5 × 106 CFU of either WT CO92 (5,000 LD50s) or its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant. Animals were sacrificed on days 2, 3, and 6 p.i., and their lungs, liver, spleen, and blood were harvested and subjected to bacterial load determination. Mice challenged with WT bacteria had a high bacterial load in each of these organs on both day 2 (ranging from 1.1 × 107 to 1.7 × 109 CFU/organ) and day 3 (1.3 × 109 to 2.8 × 109 CFU/organ). No data were collected on day 6 since all of the mice succumbed to infection within 80 h. Animals challenged with the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant had minimal to no bacterial load in the organs examined, except for the lungs on day 2 (ranging from 2.8 × 102 to 1.9 × 103 CFU/organ) (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Dissemination of WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant in a mouse model of pneumonic plague. Female Swiss Webster mice were challenged with 2.5 × 106 CFU of WT Y. pestis CO92 or its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant by the i.n. route. Organs and blood were harvested from mice (n = 5) on days 2, 3, and 6 p.i. The bacterial loads in different organs and blood from each individual mouse were plotted, and the arithmetic means are indicated by the horizontal bars. ** indicates statistical significance (P < 0.001) compared to WT CO92 on each day (day 6 was compared to day 3 for WT CO92).

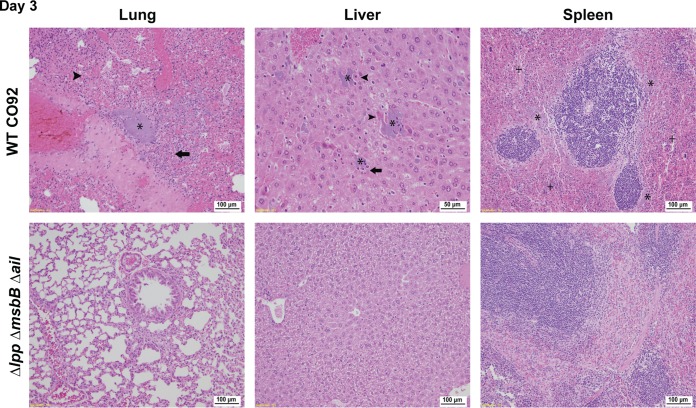

Organs from the infected mice were also removed for histopathological analysis. At between 48 and 60 h p.i., two of the five WT bacterium-infected mice succumbed to infection, and their organs were not harvested. The remaining three mice succumbed to infection at between 60 and 72 h p.i., and their lungs had mild to moderate neutrophilic inflammation (Fig. 8, arrows). All of the animals had bacteria present in their lungs (Fig. 8, asterisks), and one had mild diffuse congestion. The alveoli of all of the lungs had a moderate level of hemorrhage (Fig. 8, arrowheads), with few alveolar spaces being observed (Fig. 8). The lungs of Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected mice appeared normal, with only one animal having minimal histiocytic infiltration of the alveolus by day 3 p.i. There were no noticeable bacteria or edema present in the lungs of triple mutant-infected mice (Fig. 8). However, the lungs of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail mutant-infected mice had minimal to mild neutrophilic infiltration on day 2 p.i. (data not shown). The residual lesions in the triple mutant-infected mice resolved by day 6 p.i. (data not shown).

FIG 8.

Histopathology of mouse tissues following pneumonic infection with WT CO92 or its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant. Female Swiss Webster mice were challenged with 2.5 × 106 CFU of WT Y. pestis CO92 or the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant by the i.n. route. On days 2, 3, and 6 p.i., a portion of the lungs, liver, and spleen (n = 3 to 5) was stained with H&E and evaluated by using light microscopy in a blind fashion. Only data for day 3 are shown. The presence of bacteria, neutrophilic infiltration, hemorrhage/necrosis, and rarefied red pulp is indicated by asterisks, arrows, arrowheads, and plus signs, respectively.

All of the livers of WT-infected animals had bacteria (Fig. 8, asterisks), some necrosis (arrowheads), and neutrophilic infiltration (arrows). These lesions were nonexistent or minimal in the livers of Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected mice on day 3 p.i. (Fig. 8). All of the spleens of WT-infected mice had bacteria (Fig. 8, asterisks), mild lymphoid depletion of the marginal zone in the white pulp, and mild to marked diffuse rarefaction (Fig. 8, plus signs) or a loss of the normal cell population of the red pulp with fibrin present. The red pulp of these spleens also had moderate levels of hemorrhage on day 3 p.i. (Fig. 8). The spleens of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected mice were essentially normal, with a few animals having either minimal neutrophilic inflammation of the red pulp or mild depletion of the white pulp (Fig. 8). These changes in the spleens of animals infected with the triple mutant could be related to the generation of an immune response.

The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant of Y. pestis CO92 evokes reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines in a pneumonic plague mouse model.

Samples of the lung homogenates and sera collected from the above-mentioned infected animals were assessed for cytokine production by using an eBioscience 6-plex Bioplex assay. There was a statistically significant difference in the presence of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6 in both the lungs and the sera between the WT- and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected animals on both days 2 and 3 p.i. (Fig. 9). In the lungs, TNF-α and IFN-γ levels from WT-infected animals were >50- to 100-fold higher than those in the triple mutant-infected animals, whereas their IL-6 levels were >1,000-fold higher (Fig. 9A). In the serum, TNF-α and IFN-γ levels from WT-infected mice were >50-fold higher than those in the triple mutant-infected animals, whereas their IL-6 levels were >300-fold higher (Fig. 9B). These reduced cytokine levels in mice infected with the mutant correlated with its rapid clearance (Fig. 7).

FIG 9.

Cytokine/chemokine analysis of sera (B) and lung homogenates (A) of mice in a pneumonic plague mouse model. Mice were challenged with 2.5 × 106 CFU of WT Y. pestis CO92 or its Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant by the i.n. route. At 2 and 3 days p.i., 5 mice from each group (at each time point) were euthanized. The lungs were harvested and homogenized, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. The production of various cytokines/chemokines was measured by using a multiplex assay. Only the cytokines/chemokines showing statistically significant differences in mutant- compared to WT CO92-infected mice are plotted as arithmetic means ± standard deviations. * and ** indicate statistical significance (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to WT CO92 on each day.

Δail mutants of Y. pestis CO92 have host-dependent serum sensitivities.

Ail has been reported to function in providing serum resistance to Y. pestis (31–34). Consequently, WT CO92 and its Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutants were tested for their ability to be killed by the complement cascade. As shown in Fig. 10A, both WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant strain showed ≥100% survival upon exposure to normal unheated mouse, NHP, or human serum. Thus, the deletion of the lpp and msbB genes did not affect the serum resistance of Y. pestis. In contrast, the Δail single mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strains showed ≥100% bacterial survival in normal (unheated) mouse serum, with ∼0% survival in NHP and human sera, indicating Ail's role in serum resistance in NHPs and humans. This serum resistance phenotype of the Δail mutants in NHP and human sera was lost when the complement was inactivated, with ≥100% survival.

FIG 10.

Serum resistance and Ail production by various Y. pestis CO92 strains. Various Y. pestis strains (∼5 × 106 CFU) grown overnight were mixed with either unheated or heated sera from human, NHP, and mouse. (A) After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the number of surviving bacteria (CFU) in each sample was determined. * indicates statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared to WT CO92 for each type of serum. ND, not detectable. (B) The levels of Ail protein and DnaK in these strains were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies to Ail and DnaK.

To confirm that Ail is responsible for this phenotype, the complemented strains (Δail:pBR322-ail and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail) were exposed to normal (unheated) NHP and human sera. Both of these strains exhibited ≥100% survival (Fig. 10A), which provided further evidence that this phenotype was indeed due to the expression of the ail gene. The survival rate of >100% indicated the ability of these bacteria to replicate in sera. Essentially, similar levels of Ail were detected in the tested strains, except for those from which the ail gene was deleted, as judged by Western blotting (Fig. 10B).

Decreased adherence and invasion of Y. pestis CO92 Δail mutants in epithelial cells.

Since Ail functions in the adherence and subsequent invasion of bacteria in host cells, these virulence phenotypes of WT CO92 and its various mutants were first examined in HeLa cells at an MOI of 100 (Fig. 11AI and II). Both the Δail single mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant had similar, significantly decreased adherence (∼28%) (Fig. 11AI) and invasion (∼1.1 to 1.5%) (Fig. 11AII) compared to those of WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant (which had comparable levels, with ∼60 to 75% adherence and ∼3 to 4% invasion) (Fig. 11AI and II). Upon complementation with the ail gene, both the Δail:pBR322-ail and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail strains became adherent (∼60%) (Fig. 11AI) and invasive (∼3 to 4%) (Fig. 11AII), at levels comparable to those seen with WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant strain. In addition to depicting percentages of adherence and invasion, the actual CFU associated with adherence and invasion of the various tested cultures in HeLa cells are also shown (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). As a gentamicin protection assay was used during the experiment, the sensitivities of the various Y. pestis strains to this antibiotic were assessed. Our data indicated that WT CO92 and its various mutant strains exhibited similar gentamicin sensitivities, with MIC values of 0.125 μg/ml at 28°C.

FIG 11.

Adherence and invasion of WT Y. pestis CO92 and its mutant strains. HeLa cells (A) and A549 cells (B) were infected with various Y. pestis CO92 strains at an MOI of 100 at 37°C for 2 h. The percentages of adherent (I) and invading (II) bacteria compared to the total number of bacteria used to infect epithelial cells were calculated. The arithmetic means ± standard deviations are plotted. * and ** indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to both WT CO92 and the Δlpp ΔmsbB mutant.

Since Y. pestis infects the lungs during pneumonic plague, bacterial adherence to and invasion of A549 human alveolar epithelial cells were then examined to mimic a natural infection scenario. As with the HeLa cell infection model, both the Δail single mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant had similar significantly decreased rates of adherence (34% and 10%, respectively) (Fig. 11BI) and minimal invasion (∼0.01%) (Fig. 11BII) compared to WT CO92 and its Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant (which had comparable levels, with ∼90% adherence and ∼4% invasion). Upon complementation with the ail gene, both the Δail:pBR322-ail and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail:pBR322-ail strains showed increased adherence (∼50 to 55%) and invasion (∼1%) (Fig. 11BI and II). As for the HeLa cells, the actual CFU associated with the adherence and invasion of the various tested cultures in A549 cells are also shown (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). Thus, the decreased adherence and invasion properties of the Δail mutants were most likely due to the lack of the Ail protein.

Host-dependent survivability of Y. pestis CO92 Δail mutants in murine and human macrophages and epithelial cells.

To determine the role of Ail in intracellular survival within macrophages, MH-S murine alveolar macrophages were infected with WT CO92 or the Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, or Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant at an MOI of 10. The macrophages showed an increased uptake of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (29%) compared to WT CO92 and the Δail single mutant strain (12% and 13%, respectively) (data not shown). At 2 h p.i., 46% of the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant and 39% of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant cells survived in MH-S cells, compared to 77% of WT CO92 cells (Fig. 12A), correlating with our previously reported data showing that Lpp contributes to the intracellular survival of Y. pestis in macrophages (49, 55, 57, 60). The Δail single mutant strain had an intracellular survival rate (74%) comparable to that of WT CO92 (Fig. 12A). This trend was similar at 4 h p.i., although the percent survival of bacteria decreased further. Thus, these data suggested that Ail did not contribute to intracellular survival in murine alveolar macrophages (Fig. 12A).

FIG 12.

Intracellular survival of various Y. pestis CO92 mutant strains in epithelial cells and macrophages. Murine MH-S macrophages (A), human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDM) (B), HeLa epithelial cells (C and D), and human A549 alveolar epithelial cells (E) were infected with various Y. pestis CO92 strains at MOIs of 10, 1, 100, and 100, respectively. After 45 to 60 min of incubation at 37°C and following an hour of gentamicin treatment, the cells were harvested at 2 and 4 h post-gentamicin treatment for macrophages and at 12 h for epithelial cells. The number of bacteria surviving intracellularly was assessed, and percent survival was calculated. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05, P < 0.005, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to WT CO92 at each time point or between two tested strains, as indicated by the horizontal bars.

To further investigate the intracellular survivability of mutant bacteria, human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs) were used. The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain was most impaired in survival intracellularly (18%) in HMDMs compared to the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant (25%) and WT CO92 (38%) at 2 h p.i. (Fig. 12B). However, no statistical difference was noted when the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant were compared. This trend was similar at 4 h p.i., although the percent survival of bacteria decreased further (Fig. 12B).

We then infected HeLa epithelial cells with various CO92 mutants in two independent experiments (Fig. 12C and D). In the first set of experiments, the Δlpp single mutant and its complemented strain were also tested. As shown in Fig. 12C, WT CO92 and its Δail single mutant strain had comparable intracellular survival rates (63% and 68%, respectively), whereas the Δlpp single and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutants had decreased survival rates (31 to 32%) at 12 h p.i. On the contrary, the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain survived minimally (5%). We fully complemented the Δlpp single mutant in cis with the corresponding gene (Fig. 12C), indicating a major role of Lpp in bacterial intracellular survival. In a second HeLa cell experiment (Fig. 12D), we showed a similar pattern of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant surviving minimally, while the Δail single mutant exhibited a survival pattern mimicking that of WT CO92. Furthermore, as expected, the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant was significantly impaired in its survival in HeLa cells compared to WT CO92 (Fig. 12D). Interestingly, we were able to partially restore the intracellular survival phenotype of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant with the ail gene when provided in trans (Fig. 12D), but it did not reach the level of intracellular survival noted for the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant.

Finally, we infected A549 human lung epithelial cells with WT CO92 and its Δail single, Δlpp ΔmsbB double, or Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strain. Both the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant and Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant strains had decreased survival rates (49% and 11%, respectively) at 12 h p.i. (Fig. 12E), a pattern similar to that seen in HeLa cells. Partial complementation of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant in terms of intracellular survival was noted with the ail gene (Fig. 12E), although the data did not reach statistical significance, unlike in HeLa cells (Fig. 12D), but reached a level comparable to that of the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant.

Host-dependent inflammatory cytokine secretion by Y. pestis CO92 Δail mutants in infected macrophages.

Supernatants from the above-mentioned infected macrophages were collected and assessed for cytokine production by using either a Bio-Rad mouse 6-plex assay kit for MH-S cells or a Bio-Rad human 8-plex assay kit for HMDMs. The Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant-infected MH-S macrophages maintained levels of TNF-α and IL-6 secretion comparable to those of WT-infected cells at 2 h p.i., both of which were significantly decreased compared to those in WT-infected MH-S macrophages at 4 h p.i. (Fig. 13A). The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected mouse macrophages had significantly increased levels of TNF-α and IL-6 secretion at 2 h and 4 h p.i. compared to those of WT CO92- and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant-infected MH-S cells (Fig. 13A).

FIG 13.

Inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages infected with various Y. pestis CO92 strains. Murine alveolar macrophages (A) and human monocyte-derived macrophages (B) were infected with various Y. pestis strains. Supernatants from infected macrophages were collected at 0, 2, or 4 h after gentamicin treatment. The levels of various cytokines in the supernatants were measured by using a multiplex assay. Only the cytokines/chemokines showing statistically significant differences compared to WT CO92-infected macrophages are plotted as arithmetic means ± standard deviations. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.0001, respectively) compared to WT CO92 on each day.

The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected HMDMs had statistically significant increases in levels of TNF-α and IL-6 at 2 h p.i. compared to those in both the WT CO92- and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant-infected macrophages (Fig. 13B). The Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant-infected HMDMs secreted levels of TNF-α to comparable to those secreted by WT CO92-infected HMDMs but exhibited a significant decrease in IL-6 secretion at 2 h p.i. (Fig. 13B). Finally, while the infected MH-S cells had extremely low levels of IFN-γ, the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant-infected HMDMs secreted increased amounts of IFN-γ (63 pg/ml) at 2 h p.i. compared to those in both WT CO92- and Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant-infected HMDMs (41 and 39 pg/ml, respectively). However, the data did not reach statistical significance. Other cytokines included in the Bioplex assay were below the detection limit for the samples obtained after infection of macrophages with either WT CO92 or its mutant derivatives.

DISCUSSION

We made an in-frame deletion of the ail gene from an already existing Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant of WT strain CO92. The Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant was attenuated in evoking both bubonic and pneumonic plague in mouse and rat models (49). This double mutant retained immunogenicity to partially protect rodents against pneumonic plague upon subsequent infection with lethal doses (8 to 10 LD50s) of WT CO92 (49). Our goal was to discern whether the deletion of the ail gene from the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant of WT CO92 would further attenuate the bacterium in vivo while retaining immunogenicity, to serve as a possible background strain from which additional genes could be deleted for future live-attenuated vaccine development against plague. Indeed, the triple mutant was so highly attenuated that it did not kill any mice, even at a dose as high as 3.4 × 106 CFU (corresponding to 6,800 LD50s) of WT CO92 (Fig. 6A), and the animals did not exhibit any clinical symptoms of disease. Based on our data (Fig. 4), it was apparent that the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant was synergistically attenuated in a mouse model of pneumonic plague compared to the Δail single mutant and the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant.

In previous studies, the Δlpp ΔmsbB double mutant of Y. pestis CO92 and the Δail mutant of Y. pestis KIM5 were reported to have a decreased ability to disseminate to peripheral organs of mice compared to their respective parental strains; however, both of these mutant strains persisted for 3 to 7 days p.i. in mouse organs (44, 49). On the contrary, the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant was more rapidly cleared from animals (by days 2 to 3 p.i.) (Fig. 7), resulting in minimal histopathological changes in the lungs, liver, and spleen (Fig. 8).

The Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant produced levels of F1, Pla, and LcrV essentially similar to those produced by WT CO92 (Fig. 2 and 3), and therefore, the lower total IgG titers to F1-V antigen in the triple mutant-infected mice than those in animals that were challenged with either the Δlpp ΔmsbB or the Δlpp Δail double mutant (Fig. 4B) are most likely due to the rapid clearance of the triple mutant by the immune system and not to its inability to stimulate an IgG response. This observation was substantiated by our findings that the IgG responses increased significantly when the animals were immunized with higher doses of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant (Fig. 5B and 6B).

Brown Norway rats infected with the Δail mutant of Y. pestis CO92 were recently found not only to survive pneumonic infection (32), but also to have an influx of neutrophils in the draining lymph nodes when challenged by the intradermal route, leading to the development of large purulent abscesses (32). In addition, Ail seemed necessary for specifically targeting neutrophils for T3SS translocation of effectors in the lungs when animals were infected intranasally with either the WT strain or the Δail mutant of Y. pseudotuberculosis (71). In our study, the lungs of the triple mutant-infected animals had minimal to mild neutrophilic inflammation on day 2 p.i. The life span of neutrophils in mice is estimated to be up to 12.5 h (72), and therefore, the influx of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells in mice at the infection site by the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant at earlier time points clearly represents a possibility that will be investigated in the future.

In addition to neutrophils, Y. pestis preferentially infects host macrophages, probably via the recognition of specific surface-associated CCR5 molecules, and survives within these phagocytic cells during early stages of infection (73). The intracellular survival and growth of Y. pestis in macrophages seem to play a role in the pathogenesis of the plague bacterium, as the organism acquires the ability to evade subsequent phagocytosis (e.g., by synthesizing capsule) and is protected from contact with other immune components (74). Thus, the impaired survival of the Δlpp ΔmsbB Δail triple mutant in macrophages (both murine and human) (Fig. 12) seemed to contribute to its significant attenuation.

Although Y. pestis is a facultative intracellular pathogen (2), its ability to invade epithelial cells has been reported only recently (33, 44, 61, 75). Ail is a major mediator responsible for the adherence and invasion of Y. pestis KIM strains or when the ail gene is overexpressed in nonadherent and noninvasive E. coli strains in human epithelial cells of cervical origin (HeLa and Hep-2) (33, 34, 44, 45). Likewise, mutated versions of the ail gene from Y. pestis, when expressed and produced in E. coli, exhibited phenotypes of decreased adherence and invasion in HeLa cells, compared to E. coli strains expressing the nonmutated ail gene (75). We provided the first evidence that Ail of Y. pestis has a role in adherence to and invasion of the human alveolar A549 epithelial cell line (Fig. 11B), thus showing Ail's role in pneumonic plague.