Abstract

Edwardsiella tarda is a Gram-negative enteric pathogen that causes hemorrhagic septicemia in fish and gastro- and extraintestinal infections in humans. The type III secretion system (T3SS) of E. tarda has been identified as a key virulence factor that contributes to pathogenesis in fish. However, little is known about the associated effectors translocated by this T3SS. In this study, by comparing the profile of secreted proteins of the wild-type PPD130/91 and its T3SS ATPase ΔesaN mutant, we identified a new effector by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. This effector consists of 1,359 amino acids, sharing high sequence similarity with Orf29/30 of E. tarda strain EIB202, and is renamed EseJ. The secretion and translocation of EseJ depend on the T3SS. A ΔeseJ mutant strain adheres to epithelioma papillosum of carp (EPC) cells 3 to 5 times more extensively than the wild-type strain does. EseJ inhibits bacterial adhesion to EPC cells from within bacterial cells. Importantly, the ΔeseJ mutant strain does not replicate efficiently in EPC cells and fails to replicate in J774A.1 macrophages. In infected J774A.1 macrophages, the ΔeseJ mutant elicits higher production of reactive oxygen species than wild-type E. tarda. The replication defect is consistent with the attenuation of the ΔeseJ mutant in the blue gourami fish model: the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the ΔeseJ mutant is 2.34 times greater than that of the wild type, and the ΔeseJ mutant is less competitive than the wild type in mixed infection. Thus, EseJ represents a novel effector that contributes to virulence by reducing bacterial adhesion to EPC cells and facilitating intracellular bacterial replication.

INTRODUCTION

Edwardsiella tarda is a Gram-negative intracellular pathogen and is recognized worldwide as a causative agent of hemorrhagic septicemia in fish and is an emerging agent for gastrointestinal infection in humans (1, 2). E. tarda is able to invade and replicate in epithelial cells such as Hep-2 (3, 4), HeLa (5), and fish epithelioma papillosum of carp (EPC) cells (6), as well as phagocytic cells such as murine macrophage J774A.1 cells (7) and fish primary macrophages (6). By means of whole-genome screening approaches such as transposon tagging mutagenesis and comparative proteomics, several virulence genes have been identified and shown to contribute to E. tarda pathogenicity (8, 9). Consequently, type III and type VI secretion systems (T3SS and T6SS) were identified as two of the most important components contributing to virulence in E. tarda (6, 10).

T3SSs are assembled spanning the two cell membranes of many Gram-negative bacteria. They secrete three classes of proteins: subunits with a needle-like structure; translocon proteins, which form pores in the host membrane; and effectors, which pass through the needle channel and translocon pore into the host cell, where they manipulate cellular processes and promote bacterial virulence (11–15). Genes encoding the components of a T3S apparatus are normally clustered to form a pathogenicity island. The E. tarda T3SS gene cluster contains 35 genes (6). Deleting a single gene, such as eseB, eseD, escA, escC, or esaN, increased the 50% lethal dose (LD50) by approximately 1 log in blue gourami fish (16–18). EseB, EseC, and EseD are homologous to SseB, SseC, and SseD of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) T3SS, which are involved in the translocation of effectors (6, 19, 20). EscA is the chaperon of EseC (17), EscC is the chaperon of EseB and EseD (16), and EscB is the chaperon of EseG (18). Mutating any of these genes impairs T3SS function with the exception of EseG, the only characterized Edwardsiella effector to date, which has been shown to disassemble microtubule structures when overexpressed in mammalian cells (18).

Genes for a two-component regulatory system, EsrA-EsrB, and a regulator that belongs to the AraC family, EsrC, were found in a T3SS gene cluster of E. tarda (6, 21). EsrA is a histidine kinase sensor, and EsrB is a response regulator; EsrB binds directly to the promoters of T3SS genes to regulate their expression. In E. tarda, it also regulates expression of T6SS secreted proteins through EsrC (21, 22). The E. tarda T3SS gene cluster contains several putative genes of unknown function, such as orf29 and orf30, which are predicted to encode two effector proteins (21). orf29 and orf30 are flanked upstream by esrB and downstream by orfA, the boundary gene of the T3SS gene cluster (6). Expression of orf29-lacZ in a ΔesrC mutant strain was shown to be 4 times lower than that in the wild-type strain and more than 20-fold lower in a ΔesrA or ΔesrB mutant strain background (21). Consistently, the affinity of EsrB for the promoter region of orf29 was found to be higher than that of EsrC (22).

In this study, we show that orf29 and orf30 of E. tarda PPD130/91 actually encode one protein, EseJ. Analysis of a ΔeseJ mutant strain revealed that EseJ displays a dual function: inhibiting bacterial adhesion to fish epithelial cells and facilitating intracellular bacterial replication in host cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture conditions.

Murine J774A.1 macrophages were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 mM l-glutamine. Epithelioma papillosum of carp (Cyprinus carpio) (EPC) cells (23) were grown in MEM medium (HyClone) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM glutamine, and 18 mM NaHCO3.

Bacterial strains and culture.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. tarda strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD Biosciences) at 25°C, while Escherichia coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (LB; BD Biosciences) at 37°C. For the induction of T3SS proteins, E. tarda strains were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at 25°C under a 5% (vol/vol) CO2 atmosphere. When required, appropriate antibiotics were supplemented at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Sigma), 12.5 μg/ml colistin (Sigma), 15 μg/ml tetracycline (Amresco), and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Amresco).

TABLE 1.

List of strains used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description and/or genotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. tarda | ||

| PPD130/91 | Wild type; Kms Colr Amps | 28 |

| ΔeseJ mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of eseJ | This study |

| ΔesaN mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of esaN | 18 |

| ΔeseB mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of eseB | 16 |

| ΔeseB ΔeseJ mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of eseJ and eseB | This study |

| ΔesaN ΔeseJ mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of eseJ and esaN | This study |

| ΔesrB mutant | PPD130/91, in-frame deletion of esrB | 21 |

| ΔesaN mutant/pACYC-esaN | ΔesaN mutant transformed with pACYC-esaN | 18 |

| ΔeseJ mutant/pACYC-eseJ-2HA | ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pACYC-eseJ-2HA | This study |

| wt/gfp | PPD130/91 transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔeseJ-gfp mutant | ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔeseB-gfp mutant | ΔeseB mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔesaN-gfp mutant | ΔesaN mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔesrB-gfp mutant | ΔesrB mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔeseB ΔeseJ-gfp mutant | ΔeseB ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| ΔesaN ΔeseJ-gfp mutant | ΔesaN ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pFPV25.1 | This study |

| wt/pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | PPD130/91 transformed with pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | This study |

| ΔesaN mutant/pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | ΔesaN mutant transformed with pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | This study |

| ΔeseB mutant/pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | ΔeseB mutant transformed with pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | This study |

| wt/pACYC-gst-2HA | PPD130/91 transformed with pACYC-gst-2HA | This study |

| ΔeseJ mutant/pACYC-gst-2HA | ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pACYC-gst-2HA | This study |

| ΔeseJ mutant/pACYC-gst-eseJ-2HA | ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pACYC-gst-eseJ-2HA | This study |

| ΔeseJ mutant/pACYC-eseJ-2HA/gfp | ΔeseJ mutant transformed with pACYC-eseJ-2HA and pFPV25.1 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | α complementation | Stratagene |

| S17-1 λpir | RK2 tra regulon, λpir | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFPV25.1 | Derivative of pBR322; gfpmut3A under constitutive promoter | 27 |

| pRE112 | Suicide plasmid, pir dependent; Cmr oriT oriV sacB | 24 |

| pRE-ΔeseJ | pRE112 with eseJ-flanking fragments | This study |

| pACYC184 | Tetr Cmr | Amersham |

| pACYC-eseJ-2HA | pACYC184 with eseJ-2HA; Tetr | This study |

| pACYC-orf13::cyaA | pACYC184 with orf13::cyaA; Tetr | This study |

| pACYC-eseJ::cyaA | pACYC184 with eseJ::cyaA; Cmr | This study |

Km, kanamycin; Col, colistin; Amp, ampicillin; Tet, tetracycline; Cm, chloramphenicol.

Construction of mutant and plasmids.

A nonpolar eseJ deletion mutant was generated by sacB-based allelic exchange as described previously (21, 24). The primer pairs eseJ-for plus eseJ-int-rev and eseJ-int-for plus eseJ-rev were used to amplify DNA fragments from PPD130/91 genomic DNA. The resulting products were a 1,151-bp fragment containing the upstream region of eseJ and a 962-bp fragment containing the downstream region of eseJ. A 17-bp overlapping sequence introduced into the flanking DNA fragments permitted fusing them together by a second PCR with primers eseJ-for and eseJ-rev. The resulting PCR product, with the deletion of whole coding sequence of eseJ, was digested and ligated into the KpnI restriction site of suicide vector pRE112 (24) to create pRE-ΔeseJ and subsequently transferred to E. coli S17-1λpir (25) for conjugation with E. tarda PPD130/91. Deletion mutant strains were screened on 10% sucrose–tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates. Candidate mutant strains were verified by PCR, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. No mutant strains tested showed growth defects when cultured in TSB or DMEM. All primers used in this work are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| eseJ-frameshift-check-for | GCTGGACGCCATCGAGGACTAT |

| eseJ-frameshift-check-rev | GCAGCGCCAGGAGATCCGCGCG |

| eseJ-for | TAGGTACCGAGCCGGTGGGTCTCCACGGTT |

| eseJ-int-rev | ACAAGGCACCGGTCGTTCGCCGGAACATGGTGCGAT |

| eseJ-int-for | AACGACCGGTGCCTTGTGGATCGACCAGGGCGGTCGGGT |

| eseJ-Rev | TAGGTACCAGTATGACGTTGCCGCCGTCAA |

| ΔeseJcheck-for | AGGCCAATACCCGAAAGCCT |

| ΔeseJcheck-rev | TCATCCAGTGCGTCGTCCCGCA |

| eseJ-com-for | AGAATTCAGGCCAATACCCGAAAGCCTCCCAAT |

| eseJ-com-rev | AAGTACTTACTAGAGGCTAGCATAATCAGGAACATCATACGGATATATCGCCGCCGCCGTCTCATGC |

| eseJ-CyaA-for | GGGGTACCAGGCCAATACCCGAAAGCCTCCCAAT |

| eseJ-CyaA-rev | GAAGATCTTATCGCCGCCGCCGTCTCATGC |

| pACYC-gst-for | GAATTCAGAAGGAGATATACATATGTCCCC |

| pACYC-gst-rev | CCATGGTTACTAGAGGCTAGCATAATCAGGAACATCATACGGATATGATCCACCTCCGCCCGATCCACCTC |

| pACYC-gst-eseJ-for | GGAAGATCTATGGTGAATGCTTTTACGTTATCCCCCG |

| pACYC-gst-eseJ-rev | CGGGGTACCCTAGAGGCTAGCATAATCAGGAACATCATACGGATATATCGCCGCCGCCGTCTCATGC |

To construct ΔeseB ΔeseJ and ΔesaN ΔeseJ double mutants, pRE-ΔeseJ was transferred to E. coli S17-1 λpir (25) to conjugate with the ΔeseB or ΔesaN mutant. Deletion mutants were screened as described above.

The DNA sequence including the eseJ gene and its ribosome binding site was amplified with primers eseJ-com-for and eseJ-com-rev and ligated into the EcoRI and ScaI restriction sites of pACYC184 (Amersham) to create pACYC-eseJ-2HA. A DNA sequence encoding amino acids (aa) 2 to 406 of Bordetella pertussis cyaA (GenBank no. Y00545.1) fused at the C terminus of Orf13 of E. tarda with a linker (orf13-linker-cyaA) was synthesized by GenScript and cloned into the BamHI and SphI restriction sites of pACYC184 to create pACYC-orf13::cyaA. The eseJ gene without its stop codon was amplified with primers eseJ-cyaA-for and eseJ-cyaA-rev and digested with KpnI and BglII to replace orf13 of pACYC-orf13::cyaA, yielding pACYC-eseJ::cyaA. All the plasmids constructed were verified by DNA sequencing and transferred into E. tarda strains by electroporation for investigation.

The gst::orf13-2HA fusion gene was synthesized by GenScript and ligated into EcoRV-digested pUC57-Simple to obtain pUC57-gst::orf13-2HA, from which gst::orf13-2HA was digested and ligated into the EcoRI and NcoI sites of pACYC-184 to construct pACYC-gst::orf13-2HA. To construct pACYC-gst::eseJ-2HA, eseJ-2HA was amplified with the primer pair pACYC-gst-eseJ-for plus pACYC-gst-eseJ-rev and ligated into the BglII and KpnI sites of pACYC-gst::orf13-2HA to replace orf13-2HA and create the recombinant plasmid pACYC-gst::eseJ-2HA. For constructing pACYC-gst-2HA, gst-2HA was amplified from pUC57-gst::orf13-2HA with the primer pair pACYC-gst-for plus pACYC-gst-rev and ligated into the EcoRI and NcoI sites of pACYC-184 to create the control plasmid pACYC-gst-2HA.

Secretion assay.

Overnight cultures of E. tarda strains were subcultured at 1:200 in DMEM and grown without shaking for 24 h at 25°C. The supernatant (labeled extracellular proteins [ECP]) and the total bacterial proteins (TBP) were prepared as described by Zheng and Leung (10). Five percent of TBP and 10% of ECP were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Coomassie blue staining or transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane for immunoblotting. Membranes were probed with rabbit anti-EseJ antibody (1:2,000, raised against peptide LSGNAAGSESTESL of EseJ [positions 11 to 24] by Bio-Genes [Berlin, Germany] and purified by using specific peptide as the ligand) or rabbit anti-EvpP antibody at 1:5,000 (10) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at 1:2,000 (Millipore) and mouse anti-DnaK monoclonal antibody (Abcam) at 1:1,000 followed by goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP at 1:5,000 (Sigma). Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized with Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo), followed by exposure in a Fluor Chem Q machine (Alpha Innotech).

Identification of EseJ.

On 5% to 10% SDS-PAGE gel, a protein band between 130 and 250 kDa was observed in ECP of the wild type but not of the T3SS mutant ΔesaN strain. The band was excised and subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). To recheck the DNA sequence encoding the C-terminal region of Orf29 and the N-terminal region of Orf30 of E. tarda PPD130/91, we used high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Fermentas) to amplify the corresponding DNA with primers eseJ-frameshift-check-for and eseJ-frameshift-check-rev (Table 2). The resultant PCR product was purified and subjected for DNA sequencing.

CyaA-based translocation assay.

The CyaA translocation assay was based on a protocol reported previously (26). In brief, 24 h before infection, EPC cells were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates at 5 × 105 cells/well, and bacteria were applied to cell monolayers at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Cultures were then centrifuged at 170 × g for 5 min at room temperature (RT) and incubated at 25°C for 30 min. After incubation, the medium was aspirated, and the monolayers were washed once with prewarmed culture medium followed by incubation with medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma) for 1 h. Subsequently, the monolayer was washed once again, followed by incubation with medium supplemented with 17.5 μg/ml gentamicin for another 4.5 h. At time zero (T0; before incubation in MEM supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin) and 5.5 h postinfection (T5.5), the monolayers were lysed with 250 μl of 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) diluted in sample diluent. Plates were incubated for 10 min at 25°C to lyse the cells. The lysed cells were centrifuged, and the resultant supernatants were collected and analyzed for cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, using an enzyme-linked immunoassay according to the instructions of the manufacturer (K019-H1; Arbor Assays).

Adhesion assay by confocal microscopy.

Adhesion assays were performed as described by Tan et al. (6) with minor modifications. EPC cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per well and grown for 24 h to 100% confluence in 24-well tissue culture plates. The cell monolayers were washed once with prewarmed Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Invitrogen) and infected with E. tarda strains expressing GFP from pFPV25.1 (27) at an MOI of 10. The plate was centrifuged at 170 × g for 5 min at room temperature and incubated at 25°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min. The monolayers were washed five times with prewarmed HBSS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS (pH 7.4). The cell-associated E. tarda cells were counted from more than 15 fields of view over three coverslips per infection condition tested by using confocal microscopy.

Adhesion and internalization assay by CFU.

EPC monolayers were infected with bacterial strains as described above. At time zero postinfection (i.e., after 30 min of incubation), the monolayers were washed five times with prewarmed HBSS and lysed with 0.2% Triton X-100, and the bacteria were quantified by plating a dilution series onto TSA plates. To measure the numbers of internalized bacteria, infected monolayers were washed once with prewarmed HBSS and then maintained in MEM with gentamicin at 100 μg/ml for 1 h to kill any remaining extracellular bacteria. Subsequently, the EPC monolayers were washed five times with prewarmed HBSS and lysed with 0.2% Triton X-100 for plating. Adhesion is defined as percentage of input bacteria still adherent after washing without gentamicin treatment, and internalization is defined as percentage of input bacteria surviving after gentamicin treatment for 1 h.

Replication assay in EPC and J774A.1 cells.

EPC cells were infected as described for the internalization assay. After 1 h of 100 μg/ml gentamicin treatment, intracellular bacteria were recovered by plating, or after 1 h treatment with 100 μg/ml gentamicin, the medium was replaced with MEM containing 17 μg/ml gentamicin and incubated for a further 4.5 h before intracellular bacteria were recovered, as described above, for plating.

J774A.1 macrophages were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per well in 24-well tissue culture plates 24 h before infection. Bacterial strains were opsonized with naive mouse serum (Millipore) and added to the monolayers at an MOI of 5. The monolayers were centrifuged at 170 × g for 5 min at RT, and the infection was allowed to proceed at 35°C for 30 min. Cells were washed with and kept in prewarmed DMEM supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin for 1 h and changed to DMEM containing 17 μg/ml gentamicin for the remainder of the infection. At 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h postinfection, macrophages were washed three times with PBS, lysed with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and a dilution series was plated onto TSA plates for enumeration. Three replicates for each infection condition were analyzed, and the results were averaged.

DCF assay on reactive oxygen species from infected J774A.1 cells.

For the measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in infected J774A.1 cells, we used an OxiSelect intracellular ROS assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. J774A.1 cells (5 × 104) were seeded into 96-well plates with black walls and clear bottoms. Before infection, the J774A.1 cell monolayers were washed twice with prewarmed HBSS; the cell monolayers were then pretreated with 1 mM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) diluted in FBS-free DMEM for 40 min at 35°C, the DCFH-DA-containing mixture was then aspirated, and cell monolayers were again washed with prewarmed HBSS before infection at an MOI of 20 with opsonized wild-type or ΔeseJ mutant E. tarda strains. Standard control samples were loaded on the same plate before plate reading. Green fluorescence (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 538 nm) was detected by a plate reader (Spectramax M5; Molecular Devices) at 1 h postinfection. The assay employs the cell-permeative fluorogenic probe DCFH-DA. Nonfluorescent DCFH-DA is diffused into cells and is deacetylated by cellular esterases to nonfluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescin (DCFH), which is rapidly oxidized to highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) by ROS. The relative fluorescence units (RFU) were calculated against the standard curve.

Single-strain infection in blue gourami fish.

The experiments with fish were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Institute of Hydrobiology (permit Y213201301).

Healthy naive blue gourami fish (Trichogaster trichopterus Pallas) were infected with E. tarda as described previously by Ling et al. (28) with slight modifications. PPD130/91 wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains were cultured and subcultured separately at 25°C before injection. Doses of 106, 105, and 104 bacteria were injected intramuscularly near the dorsal fins, with 10 fish per infection. Fish mortalities were recorded over a period of 7 days. The LD50 was calculated using the method of Reed and Muench (29). For each strain, the LD50 estimation was performed at least in triplicate.

Mixed infection in blue gourami fish.

Eight naive blue gourami fish (9.20 ± 1.55 g) were used for mixed infection. Equal amounts of the wild-type PPD130/91 and the ΔeseJ mutant strains were mixed together and injected intramuscularly at 1 × 105 CFU per fish. At 72 h postinoculation, head kidneys and livers were harvested and homogenized for CFU counting. The wild-type strain was discriminated from the ΔeseJ mutant strain by using PCR to amplify the eseJ gene region with the primers ΔeseJ-check-for and ΔeseJ-check-rev (Table 2). One hundred forty-four colonies per organ per fish were examined for the ratio of ΔeseJ mutant to wild type. The competitive index (CI) is defined as the ratio of the ΔeseJ and wild-type strains within the output divided by their ratio within the input.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Data were analyzed using Student's t test, and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of eseJ has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. KF736986.

RESULTS

Identification of EseJ.

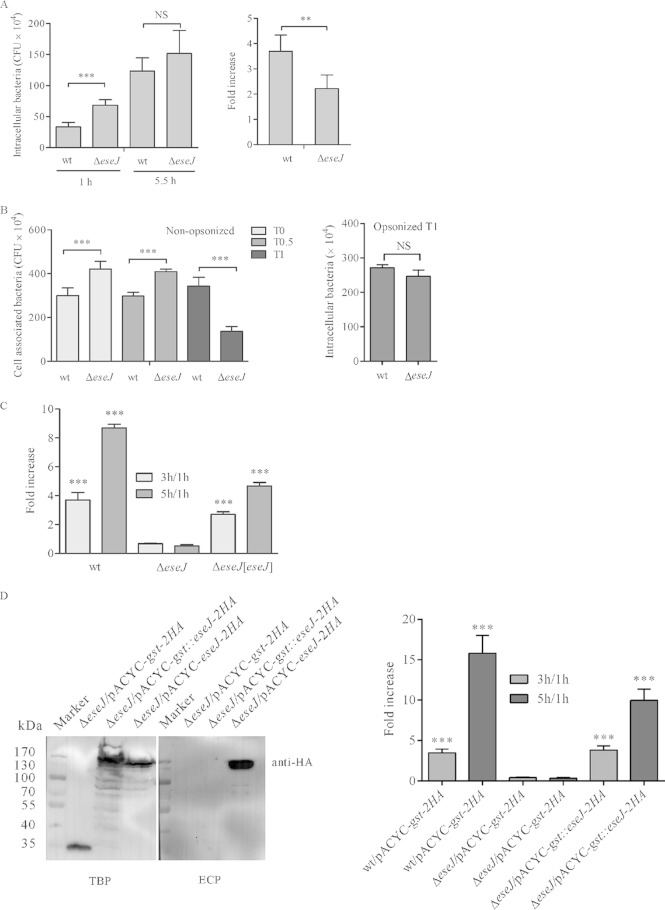

When the secretion profiles of E. tarda wild-type strain PPD130/91 and its isogenic T3SS ATPase ΔesaN mutant strain were compared on an SDS-PAGE gel, we noticed a protein band between 130 kDa and 250 kDa in the ECP of the wild-type but not in that of the ΔesaN mutant (Fig. 1). The band was excised from the gel and subjected to MALDI-TOF MS. Out of 28 peptides identified, 18 were matched with the predicted Orf29 and 10 were matched with the predicted Orf30. This suggests that the orf29 and orf30 genes of E. tarda wild-type PPD130/91 reported previously (6) could encode one protein.

FIG 1.

Secretion profiles of E. tarda strains. Samples of ECPs from similar amounts of bacteria grown in DMEM were separated using SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. T3SS proteins are EseJ, EseC, EseB, and EseD, and T6SS proteins are EvpI, EvpP, and EvpC.

To test if orf29 and orf30 are actually one gene, the DNA fragment overlapping the predicted orf29 and orf30 was amplified from E. tarda PPD130/91 genomic DNA and subjected to sequencing. The resultant sequence was found to contain 25 nucleotides more than that of the originally reported sequence (GenBank accession no. AY643478.1). Analysis of this new sequence yielded a prediction that the orf29 and orf30 genes of E. tarda PPD130/91 actually encode one protein from a single open reading frame which is composed of 1,359 amino acids and has a predicted molecular mass of 145.7 kDa. This is consistent with our observations of a protein band at a similar molecular mass after SDS-PAGE separation and with our results from the MALDI-TOF MS analysis (Fig. 1). Therefore, we renamed this gene eseJ (Edwardsiella secreted effector J). The EseJ protein of E. tarda PPD130/91 is 99% identical to ETAE_0888 of E. tarda EIB202 (GenBank accession no. YP_003294944.1) and 80% identical to the putative T3SS effector Orf29/30 of Edwardsiella ictaluri 93-146 (GenBank accession no. ABC60092). orf29/30 from E. ictaluri was also reported to be a single open reading frame based on a 6-fold sequencing coverage genome project of strain 93-146 (30).

Next, we constructed an in-frame deletion mutant of eseJ to verify the MALDI-TOF MS result. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the corresponding band of EseJ was no longer detected in the ECP of the ΔeseJ mutant strain cultured in DMEM and that it was restored in the ΔeseJ mutant strain carrying an eseJ-complementing plasmid (Fig. 1).

EseJ is secreted and translocated in a T3SS-dependent manner.

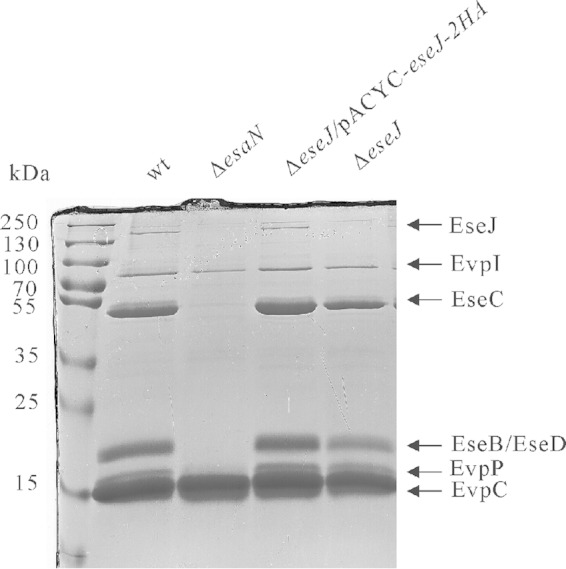

To further confirm the T3SS-dependent secretion of EseJ by immunoblotting, we raised a polyclonal antibody against a short peptide of EseJ (residues 11 to 24). The antibody specifically recognizes EseJ, as we could detect EseJ by immunoblotting only in the wild-type bacteria and eseJ-containing strains, not in the ΔeseJ mutant strain (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2A, there was no secretion of EseJ in the ΔesaN mutant strain, although EseJ was detected in the bacterial lysate. The secretion deficiency of EseJ in the ΔesaN mutant strain could be rescued using a plasmid-borne wild-type copy of esaN. The cytoplasmic protein DnaK was not detected in the secreted proteins of all the strains tested. These results demonstrate that secretion of EseJ depends on the T3SS.

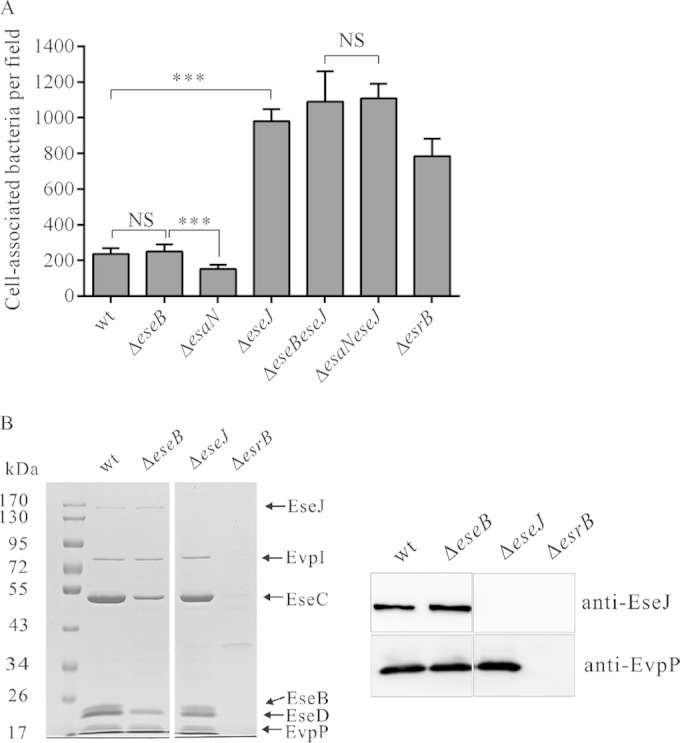

FIG 2.

Secretion and translocation of EseJ depend on the T3SS. (A) EseJ is secreted into the culture supernatant in a T3SS-dependent manner. Five percent of bacterial pellets (TBP) and 10% of culture supernatants (ECP) from similar amounts of bacteria grown in DMEM were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes for immunoblotting. (B) Translocation of EseJ depends on the T3SS. EPC cells were infected with the indicated E. tarda strains carrying the plasmid pACYC-eseJ::cyaA, and intracellular cAMP levels were determined at different time points, as described in Materials and Methods. Means ± SEM from three experiments are shown. ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

To test whether EseJ is translocated into its host cells, we constructed a reporter plasmid, pACYC-eseJ::cyaA, from which a chimeric protein EseJ::CyaA is expressed and transformed the plasmid into E. tarda strains. Fish EPC cells were infected with the wild-type strain or deletion mutant strains, i.e., the ΔesaN or ΔeseB strain (the ΔeseB mutant is a translocator mutant strain [16]), all carrying pACYC-eseJ::cyaA. Soon after infection (T0) or 5.5 h after infection (T5.5), the intracellular levels of cAMP were measured as a readout of translocation of EseJ::CyaA. As shown in Fig. 2B, the cAMP level in wild-type (wt)-infected cells was 18.20 ± 5.95 fmol per μg protein at T0, whereas it was less than 3 fmol per μg protein in cells infected with the ΔesaN or the ΔeseB mutant strain. At 5.5 h after infection, the cAMP level in wt-infected cells was increased to 114.24 ± 22.70 fmol per μg protein, while it was still less than 3 fmol per μg protein in cells infected with the ΔesaN or the ΔeseB mutant strain. These data demonstrate that EseJ is translocated into host cells and that the translocation of EseJ depends on the T3SS.

EseJ inhibits adhesion of E. tarda to fish EPC cells.

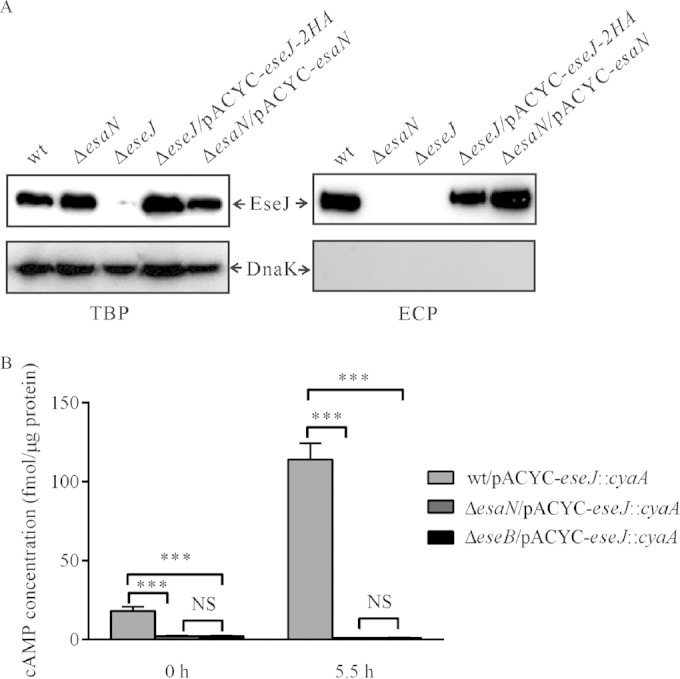

E. tarda is able to adhere to and invade EPC cells (6). To investigate if EseJ plays any role in this process, EPC cells were incubated for 30 min with different strains expressing GFP. The infected monolayers were then washed thoroughly before fixation, and 15 images per infection were taken randomly to estimate the number of bacteria associated with host cells (Fig. 3A and B). Interestingly, the association of the ΔeseJ mutant strain with EPC cells was consistently about 5 times greater than that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A and B). Complementation of the ΔeseJ mutant strain reduced the hyperadhesion phenotype back to the level of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). This indicates that EseJ plays a role in inhibiting E. tarda adhesion to EPC cells.

FIG 3.

(A and B) EseJ inhibits E. tarda adhesion to fish EPC cells. Fish EPC cells were infected at an MOI of 10 with strains expressing GFP. After 30 min of incubation (T0), cells were fixed and scanned using confocal microscopy. (A) Representative images after confocal microscopy analysis. (B) Quantification of cell-associated bacteria per field. Fifteen fields from each infection were quantified, and averages from three independent experiments are shown. Data are means ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001. (C) EseJ is not directly involved in bacterial internalization. Fish EPC cells were infected with wild-type or ΔeseJ mutant strains. After 30 min of incubation (T0; adhesion) or 30 min of incubation followed by 1 h gentamicin treatment (T1; internalization), cells were washed and lysed to enumerate bacteria by plating. The ratios of adherent bacteria to input bacteria, internalized bacteria to input bacteria, and internalized bacteria to adherent bacteria are shown. Data are means ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

To determine whether the deletion of eseJ influences internalization of E. tarda by fish EPC cells, numbers of adherent bacteria after 30 min of incubation and internalized bacteria after 30 min of incubation and 1 h of treatment with gentamicin were estimated by CFU counting. As shown in Fig. 3C, the ratios of adherent bacteria to inoculated bacteria were 7.4% for the wild-type strain and 22.1% for the ΔeseJ mutant strain. There were 0.59% of the inoculated wild type and 1.79% of the inoculated ΔeseJ mutant strain internalized. However, the ratios of internalized bacteria to adherent bacteria were 8.0% for the wild-type strain and 8.1% for the ΔeseJ mutant strain. These data suggest that EseJ inhibits adhesion but does not directly influence internalization by fish EPC cells.

To test if EseJ inhibits adhesion of E. tarda from outside or inside host cells, the ΔeseB translocator mutant strain was used in the adhesion assay. EPC cells were incubated with bacteria for 30 min, and adherent bacteria were enumerated with 15 images per infection. Similar to the wild-type strain, the ΔeseB mutant strain had about 5 times fewer adherent bacteria than the ΔeseJ mutant strain (Fig. 4A). Deleting the eseJ gene in the ΔeseB mutant strain (ΔeseB ΔeseJ) led to enhanced adhesion that was indistinguishable from that of the ΔeseJ mutant strain. In agreement with previous reports (6, 31), a ΔesrB mutant strain displayed enhanced adhesion compared with the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A). The ΔeseB mutant strain displayed no effect on the secretion of EseJ and EvpP, a protein secreted by the T6SS (10), whereas there was no detectable secretion of EseJ and EvpP by the ΔesrB mutant strain (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that EseJ inhibits bacterial adhesion from outside host cells and that this inhibition is not associated with its translocation.

FIG 4.

EseJ inhibits E. tarda adhesion to EPC cells from inside bacteria. (A) EseB and EsaN are not required for inhibiting bacterial adhesion. Fish EPC cells were infected with E. tarda strains expressing GFP and fixed to quantify adherent bacteria, as described for Fig. 3. Data are means ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant. (B) Secretion of EseJ by ΔeseB, ΔeseJ, and ΔesrB mutant and wild-type strains. (Left) Coomassie blue staining; (right) immunoblotting.

As translocation of EseJ was not required for inhibition of bacterial adhesion, we tested if secretion of EseJ is essential for inhibiting bacterial adhesion. For this, we used the ΔesaN mutant strain and a ΔesaN ΔeseJ strain for adhesion assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, the ΔesaN mutant strain displayed even less adhesion than the wild-type strain, whereas the ΔesaN ΔeseJ strain had adhesion similar to that of the ΔeseJ strain. Taken together, the data demonstrate that secretion of EseJ is not essential for inhibiting bacterial adhesion and that EseJ can function from within bacteria to inhibit bacterial adhesion.

EseJ facilitates E. tarda replication in host cells.

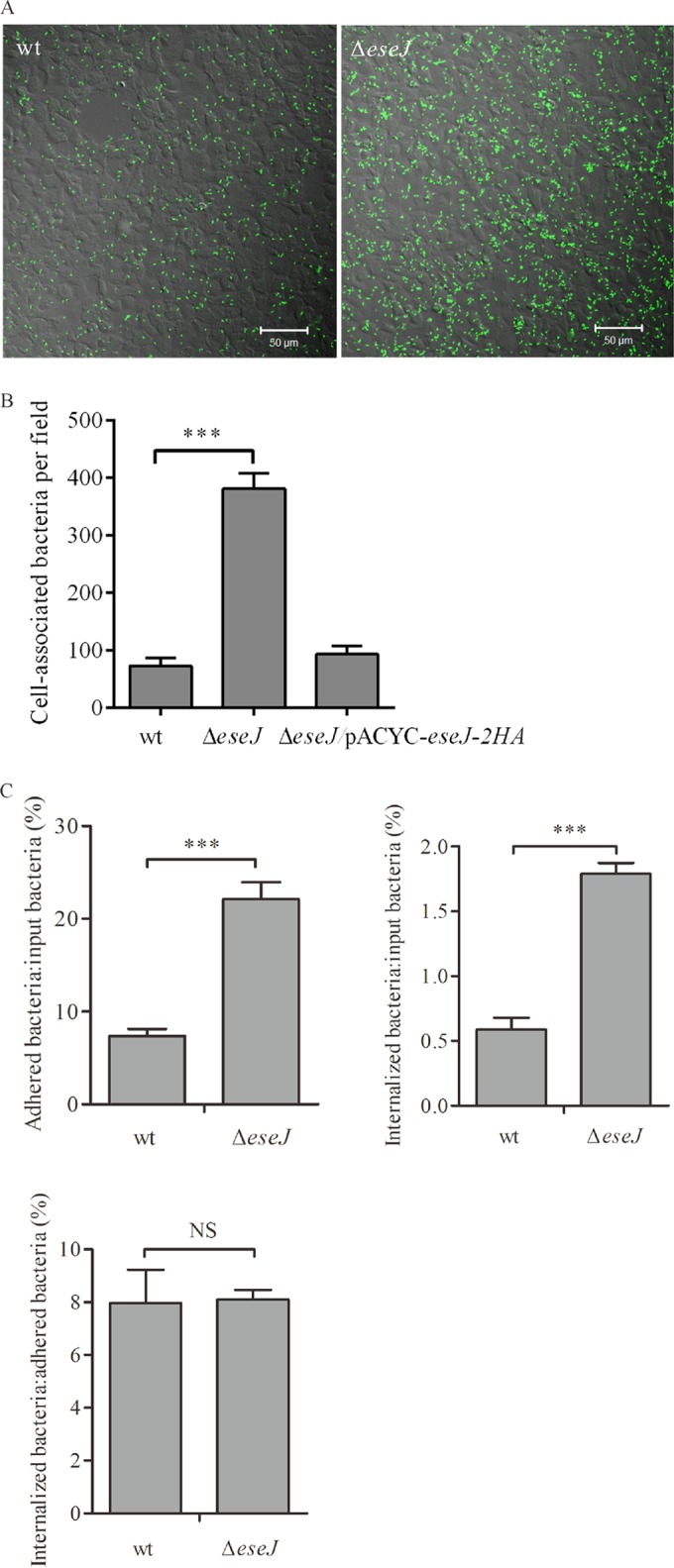

Having found that EseJ inhibits bacterial adhesion to EPC cells, we tested if EseJ could also affect bacterial replication in EPC cells. For this, EPC cells were infected with the wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains, followed by enumeration of intracellular bacteria by plating at 1 h and 5.5 h postinfection. Although the internalization of the ΔeseJ mutant strain was significantly more extensive than that of the wild-type strain at 1 h postinfection, the numbers of intracellular bacteria were similar between the wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains at 5.5 h postinfection (Fig. 5A, left). When normalized to the bacterial number at 1 h postinfection, the increase (n-fold) of the wild-type strain was significantly higher than that of the ΔeseJ mutant strain (Fig. 5A, right). This indicates that EseJ is required for efficient replication of E. tarda in EPC cells.

FIG 5.

EseJ facilitates E. tarda replication in EPC cells and J774A.1 cells. (A) Replication assay in EPC cells. EPC cell monolayers were infected by wt or ΔeseJ mutant strains and lysed at 1 h or 5.5 h postinfection for bacterial enumeration by plating. (Left) Actual bacterial numbers at the indicated time points; (right) increase. The increase was calculated as the ratio of the number of intracellular bacteria at 5.5 h to that at 1 h postinfection. Data are means ± SEM. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01. (B) Assay of uptake by J774A.1 macrophages at 35°C. J774A.1 macrophages were incubated with nonopsonized or opsonized bacteria for 30 min and lysed (T0) or infected for another 30 min (T0.5) or 1 h (T1) in DMEM containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin before being lysed for bacterial enumeration by plating. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Replication assay in J774A.1 macrophages at 35°C. J774A.1 monolayers were infected with opsonized bacteria for 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h. The intracellular bacteria were enumerated by plating the cell lysates. The increase was calculated as a ratio of the number of intracellular bacteria at 3 h or 5 h to that at 1 h postinfection. The wt and complemented (ΔeseJ/pACYC-eseJ-2HA) strains were compared with the ΔeseJ mutant strain at corresponding time points. ***, P < 0.001. (D) Blocking secretion of EseJ does not impair bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages. (Left) Expression and secretion of GST-2HA, GST::EseJ-2HA, and EseJ-2HA. Five percent of bacterial pellets (TBP) and 10% of culture supernatants (ECP) from similar amounts of bacteria grown in DMEM were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes for immunoblotting. (Right) Expression of GST::EseJ-2HA in the ΔeseJ mutant strain restores bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages. J774A.1 monolayers were infected with opsonized bacteria for 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h. The intracellular bacteria were enumerated by plating the cell lysates. The wt/pACYC-gst-2HA and ΔeseJ/pACYC-gst::eseJ-2HA strains were compared with the ΔeseJ/pACYC-gst-2HA strain at corresponding time points. ***, P < 0.001.

As E. tarda is reported to replicate in fish primary macrophages and mouse macrophages (6, 7) in addition to EPC cells, we also evaluated EseJ's contribution to replication in this cell type using J774A.1 macrophages. Expression of T3SS genes of E. tarda PPD130/91 is drastically downregulated when the bacteria are growing at 37°C; therefore, we performed infections at 35°C, conditions under which the T3SS genes are well expressed (18, 32). J774A.1 macrophages were incubated with the wild-type or ΔeseJ mutant strain for 30 min at 35°C and then washed extensively before cells were lysed for plating (T0) or for infection for either another 30 min (T0.5) or 1 h (T1) in DMEM containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin followed by bacterial enumeration. As shown in Fig. 5B, uptake of the ΔeseJ mutant strain was significantly higher than uptake of the wild type at T0 and T0.5. However, by T1, the intracellular ΔeseJ mutant was 2 times less numerous than the wild type. This indicates that EseJ inhibits uptake of E. tarda by macrophages and is required for E. tarda survival in macrophages. Next, we compared uptake of opsonized wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains by J774A.1 macrophages. Unlike with nonopsonized bacteria, there was no difference in uptake by J774A.1 macrophages at 1 h postinfection between wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains (Fig. 5B). To examine bacterial replication with a similar number of internalized bacteria, we used opsonized forms of both strains prior to infecting macrophages. At 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h postinfection, intracellular bacteria were enumerated by plating. Compared to the numbers of intracellular bacteria at 1 h postinfection, the wild-type strain's bacterial load increased 3.7 and 8.7 times at 3 h and 5 h postinfection, respectively. However, the numbers of the intracellular ΔeseJ mutant strain did not significantly increase during the course of the experiment (Fig. 5C). The replication defect of the ΔeseJ mutant was partially rescued by introducing a complementing plasmid into the mutant (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that EseJ is required for E. tarda replication in J774A.1 macrophages.

EseJ can inhibit bacterial adhesion to EPC cells from within bacterial cells (Fig. 4A), so we asked if blocking secretion/translocation of EseJ would impair bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages. To specifically block secretion/translocation of EseJ, we fused GST to the N terminus of EseJ by constructing plasmid pACYC-gst::eseJ-2HA. The plasmid was transferred into the ΔeseJ mutant strain for analysis. As shown in Fig. 5D, there was no detectable secretion of GST::EseJ-2HA. However, the intracellular replication defect of the ΔeseJ mutant could be complemented by introducing the plasmid pACYC-gst::eseJ-2HA, suggesting that blocking secretion/translocation of EseJ does not impair bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages or that a small amount of undetectable free secreted/translocated EseJ is sufficient to facilitate bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages.

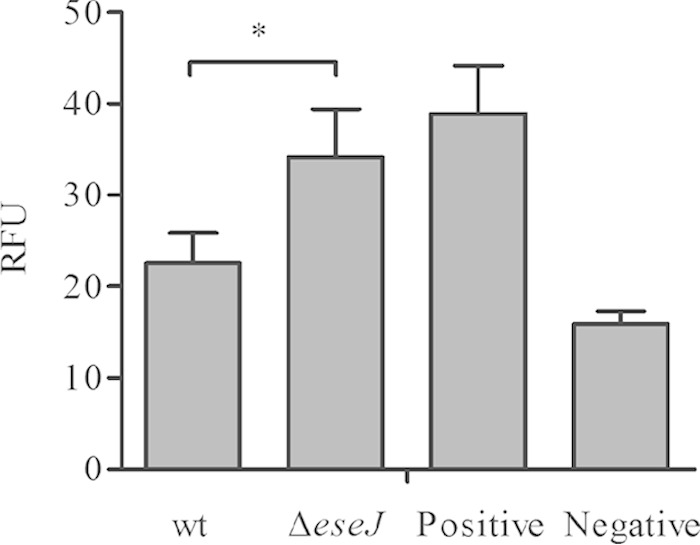

Production of ROS by wt-infected macrophages is less than that by ΔeseJ mutant-infected macrophages.

Virulent E. tarda PPD130/91 could replicate within phagocytes, while the avirulent strain PPD125/87 could not. Furthermore, only avirulent E. tarda elicited a higher production of ROS by phagocytes, indicating that the avirulent strain was unable to avoid and/or resist reactive oxygen radical-based killing by the fish phagocytes (33). The ΔeseJ mutant strain was unable to replicate within J774A.1 macrophages; therefore, we examined whether deletion of eseJ affects production of ROS by J774A.1 macrophages. Cells were infected with opsonized bacteria for 1 h, and ROS were evaluated using Cell Biolabs' Oxiselect intracellular ROS assay kit, which is a cell-based assay for measuring hydroxyl, peroxyl, or other reactive oxygen species activity within a cell. As shown in Fig. 6, the ΔeseJ mutant strain stimulated a significantly higher level of ROS than wild-type did. This indicates that EseJ may prevent the efficient production of ROS by infected macrophages.

FIG 6.

Production of ROS by J774A.1 macrophages. J774A.1 macrophages were pretreated with 1 mM DCFH-DA for 40 min at 35°C and then infected with opsonized bacteria. ROS production at 1 h postinfection was quantified by comparing it with the DCF standard curve. The negative control was considered the basal level of ROS produced by macrophages that were not infected with bacteria; the positive control was the level of ROS produced by macrophages treated with the same amount of heat-killed wild type. Results are means ± SD from one representative experiment. *, P < 0.05.

EseJ contributes to E. tarda pathogenesis in vivo.

To determine the contribution of EseJ to E. tarda pathogenesis, we determined the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the ΔeseJ mutant strain using the blue gourami fish model. In this study, LD50 refers to the minimum lethal dose of E. tarda required to kill half of the blue gourami tested within 7 days. The LD50 of the ΔeseJ mutant strain was 2.34 times higher than that of the wild-type strain (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

LD50 of the wild type and the ΔeseJ mutant of E. tarda PPD130/91

| Strain | WT protein length (aa) | Codons deleted | LD50 | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPD130/91 | 105.07 ± 0.04 | NA | ||

| ΔeseJ mutant | 1,359 | 1–1359 | 105.44 ± 0.10 | <0.01 |

| ΔesaN18 mutant | 438 | 21–421 | 105.94 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

All P values refer to the wild-type LD50 and were determined by Student's t test. NA, not available.

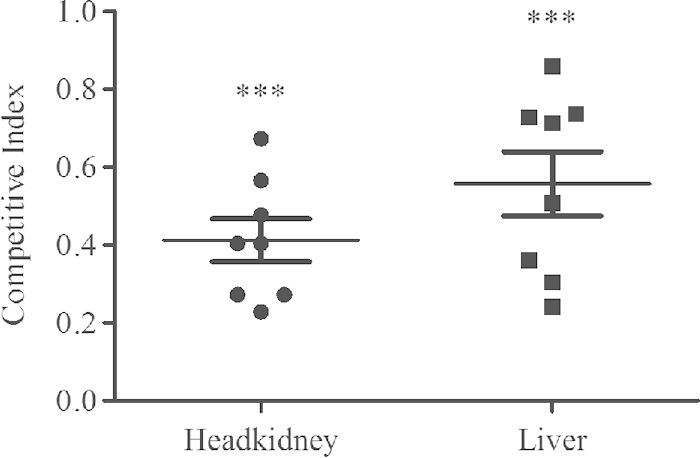

Next, mixed-infection assays were performed in blue gourami fish to test if the ΔeseJ mutant strain is less competitive than the wild-type in vivo. When equal numbers of wild-type and ΔeseJ bacteria were mixed and used to infect naive blue gourami, the ΔeseJ mutant was less competitive than the wild type in both head kidneys (CI = 0.41 ± 0.16) and livers (CI = 0.55 ± 0.23) (Fig. 7). Together, these in vivo experiments demonstrate that EseJ contributes to E. tarda pathogenesis.

FIG 7.

Competitive index analysis. Eight naive blue gourami fish were injected intramuscularly with a mixture of equal numbers of wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant bacteria and sacrificed 72 h postinjection. CIs from livers and head kidneys are given for individual fish, and means ± SD are shown by the horizontal lines. Student's t test was used to calculate the P value with the hypothetical mean of 1.0. ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

E. tarda is an intracellular pathogen that uses T3SS to facilitate its intracellular lifestyle in both epithelial and phagocytic cells (6, 7). Apart from EseG (18), little is known about T3SS effectors of this important fish pathogen. In this study, we identified the second T3SS effector of E. tarda known to date, EseJ.

Tan et al. (6) first identified the T3SS of E. tarda PPD130/91 through a combination of genome walking and PCR, and they predicted that orf29 and orf30 encode two proteins. In this study, by comparing the secretion profiles of the wild-type strain PPD130/91 and its T3SS ATPase ΔesaN mutant, we found an unknown protein band, and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry revealed that it contains the predicted protein products of both orf29 and orf30. DNA sequencing confirmed that the predicted orf29 and orf30 are actually one open reading frame, encoding a single protein composed of 1,359 amino acids, which has been named eseJ according to the established nomenclature for Edwardsiella effectors (6). Based on DNA sequence data, EseJ and its homologue are predicted to be present in E. tarda EIB202 (GenBank accession no. YP_003294944.1) and E. ictaluri 93-146 (GenBank accession no. ABC60092), suggesting that EseJ is a general effector of Edwardsiella species.

We show here that EseJ is an important virulence factor of E. tarda. Deletion of eseJ results in attenuation of E. tarda in blue gourami fish, as shown by single infection and mixed infection after intramuscular injection (Table 3 and Fig. 7). One possible explanation for the attenuation of the ΔeseJ mutant strain in vivo could be its inability to grow in macrophages. Consistently, the ΔeseJ mutant fails to grow in murine macrophage cells J774A.1 (Fig. 5). Production of ROS by macrophages plays an important role in killing intracellular bacteria and inhibiting bacterial replication (34, 35, 36). Srinivasa Rao et al. (33) reported that opsonized E. tarda PPD130/91 replicates within blue gourami phagocytes, while the avirulent strain E. tarda PPD125/87 fails to survive because it elicits higher levels of ROS in phagocytes. We found by Southern blotting that E. tarda PPD125/87 does not have the eseJ gene (data not shown). Furthermore, when comparing production of ROS by J774A.1 macrophages infected with wild-type and ΔeseJ mutant strains, we found that the ΔeseJ mutant strain elicits higher production of ROS than the wild-type strain (Fig. 6). We propose that EseJ prevents efficient production of ROS by macrophages and hence is involved in avoiding/resisting reactive oxygen radical-induced killing in macrophages, thus promoting bacterial replication.

EseJ not only facilitates growth of E. tarda in macrophages but also plays a role in bacterial adhesion to fish EPC cells. Adhesion is often an initial step critical for bacterial pathogenesis (37). Like other bacteria, E. tarda PPD130/91 utilizes fimbriae to adhere to host cells. Mutation of fimA in E. tarda PPD130/91 leads to its adhesion being 5 times lower than that of the parent strain, resulting in an attenuation in blue gourami fish after an intramuscular infection protocol (38). Fimbriae are not the only adhesin utilized by E. tarda, as several avirulent strains without the fimA gene adhere to fish EPC cells at higher levels than E. tarda PPD130/91 (28, 38). Afimbrial factors, such as hemagglutinin (39) and autotransporter adhesin AIDA (40) of E. tarda, might also be involved in bacterial adhesion. Deletion of eseJ results in enhanced bacterial adhesion to fish EPC cells (Fig. 3); the adhesion of the ΔeseJ mutant strain is 5 times greater than that of the wild-type strain when determined by direct microscopic observation and 3 times greater when assessed by CFU counting. Discrepancies between the absolute numbers obtained via the two methods may be attributed to assay sensitivity or other interassay technicalities. Nevertheless, our data demonstrate that EseJ reduces E. tarda adhesion to EPC cells. Invasion of host cells is the next process after adherence for pathogenic bacteria. Although the ΔeseJ mutant strain shows enhanced adhesion to fish EPC cells, its internalization is similar to that of the wild-type strain when internalized bacteria are normalized to the amount of adherent bacteria (Fig. 3C). This indicates that EseJ is not directly involved in E. tarda internalization. Therefore, we propose that EseJ inhibits E. tarda adherence to EPC cells. As in macrophages, EseJ is required for efficient replication of E. tarda in EPC cells. How E. tarda uses EseJ to control its adhesion to EPC cells is not clear at this stage. It is possible that EseJ represses the expression of bacterial adhesins or counteracts their function. This is supported by the following observation. (i) Secretion and translocation of EseJ are not necessary for the inhibition of E. tarda adhesion, as there is no enhanced bacterial adhesion to EPC cells for the translocator ΔeseB mutant strain and the secretion ΔesaN mutant strain (Fig. 4A). (ii) The ΔesaN ΔeseJ double mutant strain, the two-component regulatory system mutant strain (ΔesrB strain), and the ΔeseJ mutant strain show similar enhanced adhesion to EPC cells (Fig. 4A). (iii) Culture supernatant of the wild-type strain slightly but significantly suppresses the increased adhesion phenotype of the ΔeseJ mutant strain, while culture supernatant of the ΔeseJ mutant strain does not (our unpublished data).

It is clear that EseJ can inhibit bacterial adhesion to EPC cells from within E. tarda. However, it is not conclusive that secretion and translocation of EseJ are not essential to facilitate E. tarda replication in host cells. By fusing EseJ to the C terminus of GST, we observed that it blocks secretion of EseJ in vitro but still complements the ΔeseJ mutant strain replicating in J774A.1 macrophages (Fig. 5D). This seems to suggest that secretion/translocation of EseJ is not required for bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that GST::EseJ could somehow release free EseJ, which is then secreted and translocated into host cells to facilitate bacterial replication even though it is undetectable by immunoblotting.

The physiological relevance of EseJ inhibiting E. tarda adhesion to EPC cells is unclear. Several antivirulence factors have been identified in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (41–44). It is believed that these antivirulence factors prevent bacterial overgrowth in the host and enable the pathogen to be transmitted to other vulnerable hosts. Although EseJ is not directly involved in bacterial internalization, it does downregulate bacterial internalization by downregulating bacterial adhesion (Fig. 3). We speculate that E. tarda may utilize EseJ to fine-tune its interaction with host cells in the initial infection to avoid uncontrolled hostility toward its host. This could help bacteria avoid host overreaction which would trigger the immune system to kill the bacteria or decrease lethality, thereby increasing the transmission of E. tarda.

In summary, we identified a new E. tarda effector, EseJ, that plays a role in inhibiting bacterial adhesion to fish EPC cells, preventing efficient production of ROS by macrophages to facilitate bacterial replication in macrophages and contributing to bacterial virulence in fish. How EseJ regulates bacterial adhesion to EPC cells and prevents ROS production by macrophages is under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kieran McGourty (University College London, United Kingdom) for his help with the manuscript.

This work was funded by NSFC grants 31172442 and 30972278 to H.-X.X., the National Basic Research Program of China, 973 program 2009CB118703, to P.N. and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (372373-2010) and Open Funding Project of the State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering of China to K.Y.L. X.-J.Y. acknowledges support from David W. Holden and Department of Medicine, Imperial College London.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schlenker C, Surawicz CM. 2009. Emerging infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 23:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung KY, Siame BA, Tenkink BJ, Noort RJ, Mok YK. 2012. Edwardsiella tarda—virulence mechanisms of an emerging gastroenteritis pathogen. Microbes Infect 14:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss EJ, Ghori N, Falkow S. 1997. An Edwardsiella tarda strain containing a mutation in a gene with homology to shlB and hpmB is defective for entry into epithelial cells in culture. Infect Immun 65:3924–3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuda J, Kiriyama M, Yamanoi E, Nakai T. 2008. The type III secretion system-dependent repression of NF-kappaB activation to the intracellular growth of Edwardsiella tarda in human epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett 283:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques LRM, Toledo MRF, Silva NP, Magalhäes M, Trabulsi LR. 1984. Invasion of HeLa cells by Edwardsiella tarda. Curr Microbiol 10:129–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01576772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan YP, Zheng J, Tung SL, Rosenshine I, Leung KY. 2005. Role of type III secretion in Edwardsiella tarda virulence. Microbiology 151:2301–2313. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okuda J, Arikawa Y, Takeuchi Y, Mahmoud MM, Suzaki E, Kataoka K, Suzuki T, Okinaka Y, Nakai T. 2006. Intracellular replication of Edwardsiella tarda in murine macrophage is dependent on the type III secretion system and induces an up-regulation of anti-apoptotic NF-kappaB target genes protecting the macrophage from staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Microb Pathog 41:226–240. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan YP, Lin Q, Wang XH, Joshi S, Hew CL, Leung KY. 2002. Comparative proteomic analysis of extracellular proteins of Edwardsiella tarda. Infect Immun 70:6475–6480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6475-6480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao PS, Yamada Y, Tan YP, Leung KY. 2004. Use of proteomics to identify novel virulence determinants that are required for Edwardsiella tarda pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 53:573–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng J, Leung KY. 2007. Dissection of a type VI secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda. Mol Microbiol 66:1192–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galán JE, Wolf-Watz H. 2006. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature 444:567–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alto NM, Dixon JE. 2008. Analysis of Rho-GTPase mimicry by a family of bacterial type III effector proteins. Methods Enzymol 439:131–143. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa M, Handa Y, Ashida H, Suzuki M, Sasakawa C. 2008. The versatility of Shigella effectors. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:11–16. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roehrich AD, Martinez-Argudo I, Johnson S, Blocker AJ, Veenendaal AK. 2010. The extreme C terminus of Shigella flexneri IpaB is required for regulation of type III secretion, needle tip composition, and binding. Infect Immun 78:1682–1691. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00645-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buttner D. 2012. Protein export according to schedule: architecture, assembly, and regulation of type III secretion systems from plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:262–310. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05017-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Li N, Tan YP, Sivaraman J, Mok YK, Mo ZL, Leung KY. 2007. EscC is a chaperone for the Edwardsiella tarda type III secretion system putative translocon components EseB and EseD. Microbiology 153:1953–1962. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004952-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Mo ZL, Mao YX, Zou YX, Xiao P, Li J, Yang JY, Ye XH, Leung KY, Zhang PJ. 2009. Investigation of EscA as a chaperone for the Edwardsiella tarda type III secretion system putative translocon component EseC. Microbiology 155:1260–1271. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.021865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie HX, Yu HB, Zheng J, Nie P, Foster LJ, Mok YK, Finlay BB, Leung KY. 2010. EseG, an effector of the type III secretion system of Edwardsiella tarda triggers microtubule destabilization. Infect Immun 78:5011–5021. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00152-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikolaus T, Deiwick J, Rappl C, Freeman JA, Schröder W, Miller SI, Hensel M. 2001. SseBCD proteins are secreted by the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 and function as a translocon. J Bacteriol 183:6036–6045. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.6036-6045.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hölzer SU, Hensel M. 2010. Functional dissection of translocon proteins of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system. BMC Microbiol 10:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng J, Tung SL, Leung KY. 2005. Regulation of a type III and a putative secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda by EsrC is under the control of a two-component system, EsrA-EsrB. Infect Immun 73:4127–4137. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4127-4137.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakraborty S, Sivaraman J, Leung KY, Mok YK. 2011. The two-component PhoB-PhoR regulatory system and ferric uptake regulator sense phosphate and iron to control virulence genes in type III and VI secretion systems of Edwardsiella tarda. J Biol Chem 286:39417–39430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf K, Mann JA. 1980. Poikilotherm vertebrate cell lines and viruses, a current listing for fishes. In Vitro 16:168–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02831507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards RA, Keller LH, Schifferli DM. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad-host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbanowski ML, Brutinel ED, Yahr TL. 2007. Translocation of ExsE into Chinese hamster ovary cells is required for transcriptional induction of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. Infect Immun 75:4432–4439. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00664-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdivia RH, Falkow S. 1997. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science 277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling SHM, Wang XH, Xie L, Lim TM, Leung KY. 2000. Use of green fluorescent protein (GFP) to track the invasive pathways of Edwardsiella tarda in the in vivo and in vitro fish models. Microbiology 146:7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent end points. Am J Hyg (Lond) 27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thune RL, Fernandez DH, Benoit JL, Kelly-Smith M, Rogge ML, Booth NJ, Landry CA, Bologna RA. 2007. Signature-tagged mutagenesis of Edwardsiella ictaluri identifies virulence-related genes, including a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 class of type III secretion systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:7934–7946. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01115-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Wang Q, Xiao J, Liu Q, Wu H, Zhang Y. 2010. Hemolysin EthA in Edwardsiella tarda is essential for fish invasion in vivo and in vitro and regulated by two-component system EsrA-EsrB and nucleoid protein HhaEt. Fish Shellfish Immunol 29:1082–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakraborty S, Li M, Chatterjee C, Sivaraman J, Leung KY, Mok YK. 2010. Temperature and Mg2+ sensing by a novel PhoP-PhoQ two-component system for regulation of virulence in Edwardsiella tarda. J Biol Chem 285:38876–38888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srinivasa Rao PS, Lim TM, Leung KY. 2001. Opsonized virulent Edwardsiella tarda strains are able to adhere to and survive and replicate within fish phagocytes but fail to stimulate reactive oxygen intermediates. Infect Immun 69:5689–5697. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5689-5697.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vazquez-Torres A, Xu Y, Jones-Carson J, Holden DW, Lucia SM, Dinauer MC, Mastroeni P, Fang FC. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science 287:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subbian S, Mehta PK, Cirillo SLG, Bermudez LE, Cirillo JD. 2007. A Mycobacterium marinum mel2 mutant is defective for growth in macrophages that produce reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species. Infect Immun 75:127–134. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01000-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantena RKR, Wijburg OLC, Vindurampulle C, Bennett-Wood VR, Walduck A, Drummond GR, Davies JK, Robins-Browne RM, Strugnell RA. 2008. Reactive oxygen species are the major antibacterials against Salmonella Typhimurium purine auxotrophs in the phagosome of RAW 264.7 cells. Cell Microbiol 10:1058–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finlay BB, Falkow S. 1997. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:136–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srinivasa Rao PS, Lim TM, Leung KY. 2003. Functional genomics approach to the identification of virulence genes involved in Edwardsiella tarda pathogenesis. Infect Immun 71:1343–1351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1343-1351.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong JD, Miller MA, Janda JM. 1989. Surface properties and ultrastructure of Edwardsiella species. J Clin Microbiol 27:1797–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakai T, Matsuyama T, Sano M, Iida T. 2009. Identification of novel putative virulence factors, adhesin AIDA and type VI secretion system, in atypical strains of fish pathogenic Edwardsiella tarda by genomic subtractive hybridization. Microbiol Immunol 53:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho TD, Slauch JM. 2001. Characterization of grvA, an antivirulence gene on the Gifsy-2 phage in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 183:611–620. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.611-620.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouslim C, Hilbert F, Huang H, Groisman EA. 2002. Conflicting needs for a Salmonella hypervirulence gene in host and non-host environments. Mol Microbiol 45:1019–1027. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsons DA, Heffron F. 2005. sciS, an icmF homolog in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, limits intracellular replication and decreases virulence. Infect Immun 73:4338–4345. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4338-4345.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gal-Mor O, Gibson DL, Baluta D, Vallance BA, Finlay BB. 2008. A novel secretion pathway of Salmonella enterica acts as an antivirulence modulator during salmonellosis. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000036. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]